Abstract

This paper presents a conceptual and methodological framework for using Geographical Information Systems (GIS) to “deep map” cultural heritage sites along Ireland’s Wild Atlantic Way, with a focus on the 1588 Spanish Armada wrecks in County Kerry and archaeological landscapes in County Sligo’s “Yeats Country.” Drawing on interdisciplinary dialogues from the humanities, social sciences, and geospatial sciences, it illustrates how digital spatial technologies can excavate, preserve, and sustain intangible cultural knowledge embedded within such palimpsestic landscapes. Using MAXQDA 24 software to mine and code historical, literary, folkloric, and environmental texts, the study constructed bespoke GIS attribute tables and visualizations integrated with elevation models and open-source archaeological data. The result is a richly layered cartographic method that reveals the spectral and affective dimensions of heritage landscapes through climate, memory, literature, and spatial storytelling. By engaging with “deep mapping” and theories such as “Spectral Geography,” the research offers new avenues for sustainable heritage conservation, cultural tourism, and public education that are sensitive to both ecological and cultural resilience in the West of Ireland.

1. Introduction

This paper discusses the conceptualization of a Geographical Information System (GIS) to “deep map” Spanish Armada wrecks and located along Ireland’s Wild Atlantic Way tourism trail, and archaeological sites of tombs and wells in County Sligo’s “Yeats Country.” It has been observed that “for millions of years, an ancient conversation has continued between the chorus of the ocean and the silence of the stone,” with humans joining this discourse and leaving the imprints of their heritages on Ireland’s west coast relatively recently [1]. This paper aims to illustrate how digital geospatial theory and technology can draw on dialogues in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences to facilitate research and innovation in the recognition, preservation and sustainability of cultural and material heritage. The paper will first describe the GIS data methodologies employed to construct bespoke “deep map” model attribute tables. It will then consider the deep mappings of the 1588 Spanish Armada shipwreck sites in County Kerry and the archaeology of “Yeats Country” in County Sligo that influenced the work of English and Irish poets Edmund Spenser (1552–1599) and William Butler Yeats (1865–1939). It will then discuss case studies and the salience of such approaches for heritage studies and how they may complement digitization, digital restoration, and reconstruction projects that aim to sustain, and in cases excavate, cultural knowledge and assets by providing visual analyses and virtual mapping representations that support heritage pedagogy and studies, in addition to ongoing tourism and conservation initiatives, without detrimental cultural and environmental impacts.

West of Ireland Heritage Landscapes

The Wild Atlantic Way (WAW) (Figure 1) tourist trail [2] runs from the Old Head of Kinsale in County Cork to Malin Head on the Inishowen Peninsula in County Donegal. The trail unfolds across a Gaelic-speaking, western coastal region, occupied by heritage sites where human and physical landscapes, sea fishing, port and farming communities, history, memory, and myth converge, creating what scholars describe as a “palimpsest of cultural inscription” [3]. The WAW was launched in 2014 as a “branded coastal road” and “Ireland’s first long distance touring route,” and at 1553 miles (2500 km) “it is claimed to be ‘one of the longest defined coastal routes in the world,’” and “takes in some of the most spectacular, pristine and vulnerable geographical landscapes in the country” [4]. The West of Ireland’s physiography is enmeshed with dinnseanchas—oral lore about the places, names, and phenomena attached to various locations. In the ancient Gaelic world, it was the Filid (bardic poet-storyteller, historian) who engaged in this practice—with the Anglicization of Ireland, it was English and Anglo-Irish writers who carried knowledge of this tradition to the wider world.

Figure 1.

Wild Atlantic Way. collage by Charles Travis. Sources: Wikipedia and Wikimedia Commons.

As a consequence, the material landscapes of the WAW’s ports, ruins, passage tombs, holy wells and their textual representations can intersect in the traveler’s imagination as more than merely scenic backdrops, to reveal embodied, animate presences of culture and heritage [5]. The entwining of literature, landscape identity, and heritage in Ireland reflects a broader cultural geography—one that is employed in Fáilte Ireland’s tourism marketing strategies for the WAW, to frame heritage sites not only as merely physical spaces, but as places saturated with palimpsestic historical narratives and symbolism. Such campaigns are often tinted with a patina of the metaphysical to invoke the West of Ireland as a place of wonder and an a site for transcendent encounters with nature and culture [6].

2. Methodology

The doyen of Irish Geography, E. Estyn Evans, once warned that “environment without man is not environment: both are abstractions unless they are taken together,” [7] and many GIS practices in heritage studies seem to be overly positivistic and, whilst warranted for utilitarian considerations of management, preservation, and sustainability of material sites, have tended to an abstractness that elide oft intangible questions of culture [8]. Such GIS models ignore questions of what exactly constitutes heritage beyond the merely material and environmental aspects of a ruin, archaeological feature, or location of a historical event. By combining spatial technologies with archival data mining, interpretive textual analysis, and visualization, this paper’s GIS method addresses such a critique by incorporating techniques of “deep mapping,” a method defined as a richly layered cartographic practice that synthesizes physical geography, historical events, affective experience, and cultural memory to reveal the palimpsestic textures of place [9]. “Deep mapping” plots holistic “snapshots” of embodied time and place. If the evolving histories and geomorphologies of landscape can be conceptualized as a film, deep maps can be conceived of as stills taken from such films. Similar to conventional GIS practices, “the spatial considerations” of creating deep maps with digital geospatial technologies “remain the same, which is to say that geographic location, boundary, and landscape remain crucial” [9]. In addition, GIS deep mapping techniques provide a “reflexivity that acknowledges how engaged human agents build spatially framed identities and aspirations out of imagination and memory“ and can contribute “multiple perspectives” that “constitute a spatial narrative” about the geographies of a site, its culture, and its history [10]. It is the construction of “deep map” attribute tables which integrate qualitative and quantitative data and conceiving of GIS as a “database visualizer”—rather than merely a mapping tool—that can facilitate holistic heritage preservation studies between scholars and researchers in the arts, humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences.

GIS Deep Map Attribute Tables

Deep mapping of County Kerry’s Spanish Armada 1588 wreck sites, parsed by Edmund Spenser’s poetry, and the archaeological landscape of “Yeats Country” in Country Sligo resulted from visualizations of qualitative and quantitative data hosted in bespoke GIS attribute tables. The tables were created using MAXQDA 24 textual analysis software to mine place names and locational data listed in various documents. Historical, archaeological, and climatological accounts, alongside the literary texts of the English Poet Edmund Spenser (1552–1599), the Irish Poet William Butler Yeats (1865–1939), and folklore accounts of Counties Sligo and Kerry were digitized, converted to PDF format, and imported into MAXQDA 24 software for textual analysis. Texts were systematically coded to extract references to place names, geographic coordinates, and environmental conditions, and subsequently this information was mapped in Google Maps to geocode the data with latitude and longitude and decimal degree coordinates. This generated KML (Keyhole Markup Language) files, which were imported into ArcGIS Pro 3.4.3. using the KML-to-Shapefile tool, creating formal GIS shape layer files. The attribute tables of these files were exported, integrated, and merged with Open-Source Archaeological data from Ireland’s National Monument Service [11] to create bespoke geo-attribute tables that were reimported into ArcGIS Online and saved as hosted features layers that could be visualized in the online geo-apps ArcGIS Map Viewer, ArcGIS Story Maps, Instant Apps, Experience Builder and Dashboard. These proprietary apps generate embed codes allowing maps, charts, and other visualizations to be added easily to tourism websites and other online platforms to encourage digital interactivity with cultural and natural landscapes. This paper’s mappings also incorporated a digital elevation model (DEM) of Ireland’s topography to produce “deep mapping snapshots” of Armada wreck sites and Yeats Country’s archaeological heritage. DEMs are digital terrain GIS layers, formed from a grid of regularly spaced points with associated elevation values. As a foundational tool in geospatial analysis, DEMs provide 3D views of regional surfaces without buildings or vegetation. Derived from LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) satellite and Aerial Photogrammetry remote sensing methods, DEMs are typically used in land use planning, environmental studies, navigation, and most recently in historical, literary, and spatial humanities GIS applications.

Visualizations and analyses based on GIS Deep Mapping database formatting techniques and methods can facilitate more holistic and multi-dimensional perspectives of such sites to aid in their conservation and sustainability. They can also be employed to foster new, more sustainable, eco and cultural tourism initiatives and the means for tourists to read, digitally interact with, and cultivate “deeper” appreciations of heritage landscapes. For instance, heritage climatology traditionally is an applied, interdisciplinary field that examines how atmospheric conditions and weather affect the environments and material culture of existing heritage sites. In contrast, this paper will discuss how climate and weather play parts in creating climate heritage sites—which in turn can be deployed in public education initiatives to mitigate the effects of global climate change. GIS Deep Mapping database construction in this paper is also framed by theoretical paradigms in literary and historical GIS and “Spectral Geography.” The latter is a theoretical and methodological lens engaged by cultural geographers to trace how landscapes retain residual presences of faded communities’ traumatic histories—such as the Armada shipwreck, the English colonization of Ireland, and the cultural erasure of Gaelic-speaking communities—through material remains, ancestral memories, and the identification, promotion, and preservation of heritage sites [12]. Derek P. McCormack argues that “geographers have sought to engage with how the sensing of spectrality can be undertaken through writing … through encounters with the affective affordances of sites of memory and memorialization,” such as the Spanish Armada wreck sites and Yeats Country heritage landscapes mapped in this paper [13]. The following subsections discuss and contextualize the respective deep mappings of these heritage sites drawing upon climatic, literary, historical, and folkloric accounts.

3. Results

The following subsections discuss the results of “deep mapping” the locations of Spanish Armada Wreck sites along the coast of Ireland and the clusters of passage tombs and holy wells in County Sligo’s “Yeats’ Country.”

3.1. Spanish Armada Wreck Sites: Historical Climatology as Heritage

The destruction of the Spanish Armada along the rocky shores of the west of Ireland in September 1588 “is probably the most widely known example of a turning point in history in which the weather played some part,” [14] and also illustrates that “history provides the material that geography alone can weave into shape” [15]. As a consequence, the northern, western, and southern coasts of Ireland serve as “Spectral Geography” and climate heritage sites for the Armada’s ships and sailors and their Irish allies. Drawing on documents in Irish, European-Reformation War, and Maritime history, geomorphology, and climatological and navigational studies of the Spanish Armada, bespoke GIS attribute tables of place names, historical, climatological, and wreck site data were merged with locational data mined from Spenser’s poetic texts. This enabled the mapping of proximate shipwreck sites during the time Spencer was an English colonial administrator residing at Kilcolman Castle, whilst also contextualizing the historical, climatological, and weather of the Armada’s disaster that echo in his poems Virgils Gnat (1591) [16] and The Faerie Queen (1596) [17].

3.1.1. Historical Geography Overview

In late August 1588, Lord Deputy William Fitzwilliam, appointed by Queen Elizabeth to govern Ireland, received false intelligence that, with the Royal Navy defeated in the English Channel, the Spanish Armada was now preparing to invade Ireland. In the “Pale,” panic rolled through the halls of Dublin Castle—the headquarters of English colonial administration in Ireland—as Spanish ships began to appear in September off the horizon of the west coast of the island. In Fitzwilliam’s fevered imagination, the first wave of a coordinated attack in support of Irish rebellion against English rule was commencing. The truth, which became apparent as Spanish shipwrecks started to litter the coast during the tempestuous month of September 1588, was exactly the opposite. Whilst poor navigation played a part, the weather, climate, and atmospheric conditions of the Little Ice Age (1300–1850) contributed significantly to creating the heritage sites of the Armada wrecks on the west coast of Ireland [18].

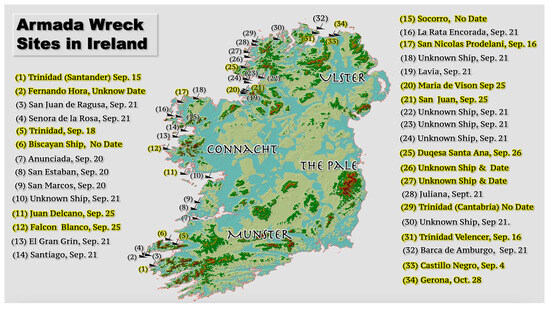

The debacle began in the port of Lisbon on 29 May 1588, when Admiral Medina-Sidonia issued orders for the 130 ships of Catholic King Philip II of Spain’s “Invincible Armada” to hoist anchor. It took two full days for the Man ‘O Wars, outfitted with twenty-five hundred guns, and other vessels to clear port. Philip’s campaign to invade and depose Elizabeth I of England, defender of Protestantism, was underway, instigated by the Virgin Queen’s support of a rebellion against Spanish rule in the Netherlands. After a series of disastrous naval battles in the English Channel, Medina-Sidonia abandoned the campaign on 11 August 1588. Blocked on the west by English warships, his Armada sailed into the North Sea and up the east coast of England. By 20 August, Armada logs record its ships sailing 400 miles in three days, before sighting the northern coast of Ireland. Storm winds then drove the fleet out to Rockall, a granite islet jutting out of the North Atlantic 300 nautical miles north of Ireland [18]. On 25 August, the Admiral held conference on the San Martin and decided to sail to Galicia, Spain. However, other Armada captains, with crews dying from hunger and thirst, struck out for Ireland. Lacking proper charts and experience sailing in the North Atlantic’s currents, the ships were caught by a series of storm fronts and began to founder on Ireland’s coasts. Fortunate captains sailing downwind from Rockall found shelter in Donegal Bay, but windward vessels were driven down the treacherous coastlines of counties Mayo, Clare, Galway, and Kerry, only to be pounded into flotsam and jetson, their remains poking like broken rib cages from the surf. Based on data collated from several sources, at least 34 wreck sites have identified in Ireland (See Figure 2) although it has been speculated that many as 37 ships could have been sunk [18]. In the end, only 30 Armada ships out of the 130 launched from Lisbon would return, with the majority of falling victim to battles in the English Channel or to Little Ice Age storms that developed in the North Atlantic in August, September, and October of 1588.

Figure 2.

The locations of 34 identified wreck sites in Ireland, based on the collation of several sources—although it has been speculated that many as 37 ships could have been sunk. Ship names and locations labelled in all white are vessels reported to have been wrecked during the Great Gale of 20–21 September 1588. Map by Charles Travis. DEM metadata: Data Type: Tin. Triangulation Method: Delaunay Conforming. Total Points: 130,813. Total Edges: 593,586. Total Triangles: 197,862. Z Range: −52.000000–1020.000000.Z Unit conversion factor: 1.000000. Projected Coordinate System:TM65_Transverse_Mercator.

Generally, sources record that five ships wrecked off the province of Munster on Blasket Island, the Shannon estuary, and Co. Clare coast. In Connaught, seven ships were wrecked in Galway Bay, on Clare Island, in Blacksod Bay, and in Broad Haven, County Mayo and at Streedagh Strand, County Sligo. In Ulster, five ships foundered in Killybegs Harbour and on the coast of Inishowen peninsula in County Donegal [14].

3.1.2. Climatic Conditions

The Clerk of the Council of Connacht Province described the “Great Gale” of the 20th and 21st of September 1588 that wrecked at least 17 Spanish ships on the coast of Ireland as a “a most extreme wind and cruel storm, the like whereof hath not been seen or heard a long time” [14]. Atmospheric conditions of the Little Ice Age (1300–1850 CE) coincided with the inauguration of early modern oceanic warfare. Temperatures in the North Atlantic Ocean experienced a pronounced decline due to the combined impacts of orbital forcing, shifts in oceanic circulation, low solar radiation cycles, and an increase in volcanic eruptions that created cooling effects by releasing particulate matter into the Earth’s atmosphere [18]. Expedition logs kept by Captain M. John Davis in 1586–1587 record that the Denmark Strait, just under the parallel line of the Arctic Circle, at latitude 66° N, between Greenland and Iceland was “mightily pestered with [i]ce and snow, so that there was no hope of landing: the [i]ce lay in some places tenne leagues, in some 20. and in some 50. leagues off the shore” [14]. Logs also revealed that Greenland’s ice extended south to latitude 57° N and longitude 47° W, where the Labrador Sea flowed into the North Atlantic [14]. Climatic and weather data from the sixteenth century has been collected by researchers from Spanish Admiral Medina Sidonia’s diaries, the logs of surviving Armada ships, Danish weather records kept by Tycho Brahe, Richard Hakluyt’s Voyages and Discoveries, (1598–1600), and other chronicles of the period [14]. Collectively these sources suggest that, in August and September of 1588, as the Armada was rounding Scotland to head south to Spain, prominent high-pressure fronts extended south from the Arctic into the North Atlantic. In turn, fronts pushing up from Western Europe stalled in a zone stretching from southern Iceland to Denmark, marked by significantly strong thermal gradients, indicating the presence of a very powerful jet stream driving weather eastward [14].

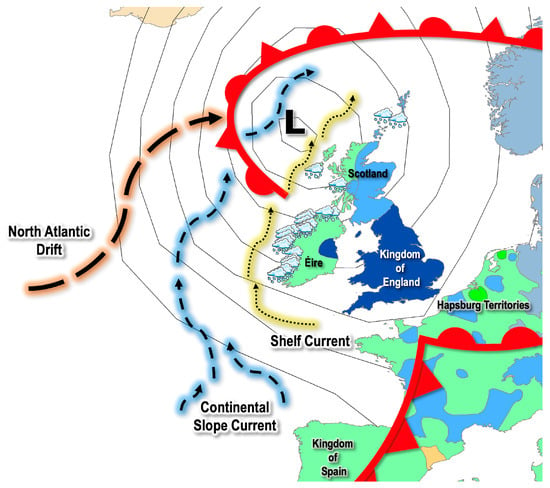

A GIS deep map meteorological reconstruction (contextualized by the political geography of Reformation War Europe) based on collated sources illustrates the atmospheric and oceanic conditions of the Great Gale of 20–21 September [14]. The map in Figure 3 displays an occluded front (formed when the cold front of a depression catches up with the warm front, lifting the warm air between the fronts into a narrow wedge) moving northwest across western Europe. Moving southeast from the North Atlantic over Ireland, Scotland, and England, a major low pressure zone brought a significant and organized line or trough of precipitation and wind. Isobars indicate regions with equal mean sea-level pressures as they dropped across the atmospheric breadth to the center of the storm. In addition, the Gulf Stream rising up from the South Atlantic was uncharted and poorly understood by ship navigators in 1588. Its flow resolves into three distinct currents as it reached the coastal shelf of Western Europe: the North Atlantic Drift and the Continental Slope and Shelf Currents [14]. Consequently, the natural forces of wind, precipitation, and currents on 20–21 September conspired to wreck 17 vessels (5 on the coast of Munster out of the 10 relevant to Spenser’s literary heritage) out of the 34 to the speculated 37 Spanish Armada ships that eventually foundered on Irish shores.

Figure 3.

Storm Front of The Great Gale of 20–21 September 1588 and Northeastern Atlantic Currents. Map by Charles Travis based on collated historical climate data sources [18]. Projection Geographic Coordinate System, Datum and Spheroid: WGS 1984.

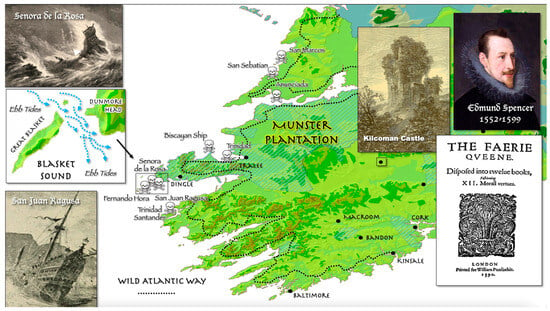

3.1.3. Edmund Spenser and the Spanish Armada

The English poet Edmund Spenser moved to Ireland in 1580 to serve as a secretary to several English colonial officials before being appointed himself as Sheriff of Cork in the Munster Province. In 1588 he was ordered to hunt Armada survivors. Consequently, Spenser’s impressions of the Catholic-Protestant European Reformation Wars and wreck of the Armada echoed in his poems Virgils Gnat [16] and The Faerie Queen [17]. The shipwrecks most proximate to Spenser’s Kilcoman Castle in Cork include the Senora de la Rosa and the San Juan De Ragusa, which had sought shelter in the Blasket Sound between Great Blasket Island and Dunmore Head on the Dingle Peninsula in County Kerry [18]. In the sixteenth century, the five-mile channel was poorly charted, and its tides ran a swift five knots, with a seabed containing iron deposits that skewed compass readings, all which made the passage a tricky passage of water to navigate, and “at best a poor anchorage in calm weather” [18]. Its currents flowed northward during the incoming “Flood Tide” and southward during the receding “Ebb Tide” [18]. Oral histories taken from Blasket Sound Filid (bardic poet-storytellers) record that any northwest gale coming of the Atlantic would shoot “straight down the Sound and blow any vessel not overwhelmed by the sea out the other end like a dart from a blow gun” [18]. The Filid recounted that the Great Gale of 20–21 September 1588 hit the two sheltering Armada ships “with terrible fury,” [18] recalling that

… when [the ships] came to the Blasket Strand there was a heavy current passing through a little gap there and they call it “the Ebb Tide” and it was a very bad place but they insist that they were stranded. They [didn’t] know the right place to anchor and they let their anchors out in the middle of the tide and the tide was so strong they drifted, drifted down and they had to let their anchors go [18].

Dragged from their anchors in gale-force winds, the two ships collided. With the tide turning, the Nuestra Senora, under the command of Prince d’Ascoli, son of the King of Spain, then swung broadside, struck Stromboli Rock, and sunk with all souls on board. The San Juan later wrecked on the Dingle Peninsula. Its surviving sailors were hunted down by English soldiers, presumably under Spenser’s command, who, like the ancient Roman poet paying homage to the might of the Roman Empire, possessed an ambition to be an English “Virgil” of the Elizabethan era [18]. Consequently, the adventures of the knights in his epic The Faerie Queen [17] can be read as “a transcript of the warfare” between England and the Gaelic chieftains allied to the Spanish in the Reformation Wars flaring across Europe [18]. Spenser’s poem portrays Irish rebels as savages rushing out of dark forests to attack his knights.

As a Munster Plantation shareholder and Protestant landlord to a largely Gaelic, Catholic peasantry, Spenser despised the Irish and wrote that “they looked Anatomies of death, they spake like ghostes crying out of their graves; they did eat of carrions …” [18]. With its “trackless woods and unexplored fastnesses, Ireland provided a fit theatre for the ambushes, temptations, and enchantments against which Spenser’s champions of virtue must be continually on guard” [18]. Joining hunting parties to capture Armada survivors and their Gaelic allies, Spenser “certainly beheld the immense wreckage of Spanish ships on the coasts of Connaught and Ulster” [18]. Metaphors in Spenser’s poem Virgils Gnat [16] of “storms and ships wrecked in tempestuous seas” symbolize the “toppling of monumental edifices by natural elements” and “celebrate the defeat of Catholic Rome” and its ally “Spain under Philip II, whose Babylonian pride” and Armada “was humbled by little England with the help of the ‘winds of God’” [18]. In turn, the defeat of the evil tyrant Souldan in The Faerie Queene [16] speaks to the destruction of the Armada on the Irish coast and the English victory over Gaelic chieftain and Earl of Tyrone, Lord Hugh O’Neill. In “Book V” of the poem, Souldan’s chariot crashes in battle, an allegory for King Philip’s Spanish wrecks littering the “green” shores of Ireland:

Quite topside turuey, and the pagan hound

Amongst the [i]ron hookes and graples keene,

Torne all to rags, and rent with many a wound,

That no whole peece of him was to be seene,

But scattred all about, and strow’d vpon the greene(FQ, V.viii.42–3) [17].

English colonial administrators reported that many Armada survivors washed ashore were murdered by “the wild Irish tempted by the sight of gold chains and rings” [18]. Conversely, Catholic Gaelic chieftains, sympathetic to the Spanish cause, attested that Armada crews, including sailors from Ireland, were slain by soldiers of the provincial English garrisons. GIS deep mappings contextualize atmospheric and oceanic conditions within the context of the European Reformation Wars of the sixteenth century when the “Armada Gale” was weaponized in tracts and pamphlets published by Protestant printers in England and the Low Countries of Flanders and the Netherlands, who declared “God was fighting against the Spaniards” [18]. In turn the King of Spain, musing on his ill-fated Armada, lamented to his advisors that “I sent them to fight the English, not storms” [18].

3.2. Mapping the Heritage Sites of Tombs and Holy Wells in Yeats Country

William Butler Yeats’ grave at Drumcliff Church in County Sligo is the heart of “Yeats Country,” a region that is also an archaeological landscape featuring approximately 1618 megalithic passage tombs and 32% of the Republic of Ireland’s approximately 3776 holy well heritage sites [11]. A simple limestone marker is engraved with verses from one of Yeats’ final poem, Under Ben Bulben (1939): “Cast a cold eye/On life, on death,/Horseman, pass by!,” [19,20] intimating the spectral geographies of the Sligo landscape mapped from dinnseanchas (the lore of places and their names) in his writing. Yeats observed that “legends are always associated with places, and not merely every mountain and valley, but every strange stone and little coppice has its legend, preserved in written or unwritten tradition” [21]. Such natural features, enhanced by Yeats’ Irish storytelling collections, played figurative and symbolic roles in constructing the mystical and mythological senses of place of heritage sites of Sligo’s “Yeats Country.” This is echoed in humanistic geographer Yi-Fu Tuan’s observation that “place is in touch with one’s roots, deeply personal, communal, and human […] place is folklore” [22]. In an 1889 letter, Yeats wrote that his drama Island of Statues comprised a “region,” illuminating how the poet conceived of his pieces of writing as distinct “geographies” with cadences and imagery emphasizing the distinct “senses of place” binding the textual, physical, built, and archaeological landscapes of his native Sligo together [19].

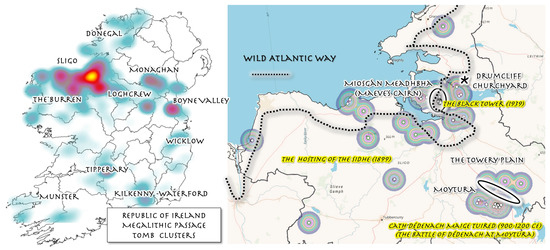

Deep mapping of the archaeological heritage of megalithic tombs and holy wells inhabiting Yeats Country conjures up the spectral geographies operating at the intersections of Sligo’s mythical, historical, and present heritage landscapes. An open-source National Monuments Service—Archaeological Survey of Ireland comma separated value (CSV) geo-attribute file containing latitude and longitude and other information on 16,252 cairns, cists (ossuaries), barrows, high crosses, megalithic tombs, castles, ringforts, holy wells, and ritual sites was downloaded. Megalithic Passage Tomb and Holy Well heritage site datasets were processed in Microsoft Excel for locations in the Republic of Ireland and in County Sligo. The Excel datasets were exported into ArcGIS Pro and transformed by the XY Table to Point Tool to create point shape files of tomb and holy well locations. Using the buffering, proximity, and heat map analysis tools in ArcGIS Pro 3.4.3, the study identified heritage site clusters (Figure 4) in County Sligo and their spatial correlations with settings and the “regions” of Yeats’ literature. In turn, the poet’s work attaches flesh, muscle, and the intangible dimensions of a “sense of place” to the bare bones of the archaeologic sites of tombs and holy wells often plotted and quantified as statistical landscapes.

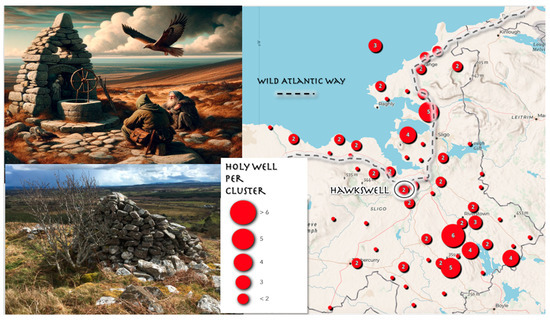

Figure 4.

Environmental and historical GIS digital elevation model (DEM) reconstruction of Blasket Sound, the Dingle Peninsula, and the Munster Plantation (c.a. 1580s) visualizing the topography of the coastal terrain of southwestern Ireland counties Cork, Kerry, and Clare, with Armada wreck sites and locations pertinent to Edmund Spenser’s tenure as Sheriff and English colonial administrator. Map by Charles Travis based on collated sources. DEM metadata: Data Type: Tin. Triangulation Method: Delaunay Conforming. Total Points: 130,813. Total Edges: 593,586. Total Triangles: 197,862. Z Range: −52.000000–1020.000000.Z Unit conversion factor: 1.000000. Projected Coordinate System:TM65_Transverse_Mercator.

3.2.1. Sligo’s Tombscape Heritage

Across the landscape of Ireland, megalithic passage tombs occupy four major clusters and six minor clusters, as illustrated in the Figure 4 heat map. The major clusters comprise the Newgrange, Dowth, and Knowth tomb complexes, which sit in the Boyne Valley, and the Loughcrew tombs, which rest in County Meath. Sligo is home to two great megalithic passage tomb complexes, with Knocknarea, Carrowmore, and the Cairns Hill complex straddling the Cúil Irra peninsula and the Heapstown, Carrowkeel, and Keshcorran sites adjacent to Lough Arrow, near the Sligo-Roscommon county border. Six minor complexes are located in the Ulster Counties of Monaghan, Donegal, the karstic landscape of the Burren in Connaught, the Munster counties of Cork, Kerry, Tipperary, and Waterford, the latter straddling the Leinster border with Kilkenny, and County Wicklow [23]. The results of GIS spatial analysis (Figure 5) of the locations and density of tomb sites clusters in the Republic of Ireland reveals that Sligo hosts nearly 7% of all Ireland’s passage tombs, with the majority of these sites concentrated on the county’s Cúil Irra peninsula, a setting for several pieces of Yeats’ poetry and drama [19].

Figure 5.

(Left): Heat map of Republic of Ireland megalithic tomb sites, with largest cluster in County Sligo. (Right): Sligo’s megalithic passage tomb heritage sites and correlations with selections of W.B. Yeat’s work. Map by Charles Travis. Projection Geographic Coordinate System, Datum and Spheroid: WGS 1984.

Approximately nine kilometers southwest from Yeats’ grave at Drumcliffe sits Knocknarea, a three-hundred-meter-high limestone mountain, looming over Sligo’s Cúil Irra peninsula. Upon its summit sits a large cairn, named Miosgán Meadhbha (Maeve’s Cairn) after Medb, the mythological-age queen of Connacht [23]. A poem, The Black Tower [24], about Knocknarea was dated 21 January 1939, and was the last poem composed by Yeats. Seven days later the poet was dead, and seven months after that, Hitler and Nazi Germany invaded Poland, igniting the Second World War. In this sense, the poem’s “story of besieged soldiers, departed king, and marshalled rivals” responds “obliquely to the politics of the late 1930s” [19]. Knocknarea was also site of the early medieval tomb of the King of Connacht, Eoghan Bel, who was interred vertically in 537 CE and rests under a large mound of scattered limestone shards and stones: “There in the tomb stand the dead upright,/But winds come up from the shore:/They shake when the winds roar,/Old bones upon the mountain shake” [24]. In The Black Tower [24], the burial mounds on the summit of Knocknarea serve as symbolic passages between the mythologies of the island’s Iron Age and the “filthy modern tide” of the twentieth century. In Red Hanrahan’s Song About Ireland (1890) Yeats imagines that “[t]he wind has bundled up the clouds high over Knocknarea,/And thrown the thunder on the stones for all that Maeve can say” [25]. In The Wanderings of Oisin (1889) Yeats depicts a hunting party chasing a stag, and after “… passing the Firbolgs’ burial-mounds,/Came to the cairn-heaped grassy hill/Where passionate Maeve is stony-still;/And found on the dove-grey edge of the sea” [26]. As intimated in the poem, the Miosgán Meadhbha mound is subject to the North Atlantic’s weather, and particularly the wind, which in the mythological imagination manifest as the “Sidhe,” a supernatural people who reside in the folklore landscape of Gaelic Ireland [19].

In The Hosting of the Sidhe (1899), Yeats writes: “The host is riding from Knocknarea/and over the grave of Clooth-na-bare“ [27]. This is Yeats’ Gaelic transliteration of the spectral figure of Cailleach Bhérra (Old Woman or Hag of Bare) who “went all over the world seeking a lake deep enough to drown her faery life, of which she had grown weary” [28]. According to Yeats, she “flew, …from hill to lake and lake to hill, and setting up a cairn of stones wherever her feet lighted” [28]. Wielding “geotectonic powers,” the Hag of Bare drops stones from the sky as she glides over the landscape, carving the valleys and hills of the peninsula, and providing a Gaelic geomythological explanation for the glaciation processes that shaped Sligo’s wider physical geographies [19]. Although only one peak in Sligo’s Ballygawley Mountains is denoted Cailleach Bhérra, “the entire cluster of hills” can be perceived as forming “the landscape of her folkloric presence” [19].

Scouring Sligo’s folkscapes for mythical stories, Yeats learned of “the great battle the Tribes of the goddess Danu fought, according to the Gaelic chroniclers, with the Fomor at Moytirra, or the Towery Plain” [19]. The Moytura townland where in Irish mythology The Last Battle of Mag Tuired (Cath Dédenach Maige Tuired)—a legend recorded between 900 and 1200 CE—took place, sits adjacent to the 3140 acre spring-fed Lough Arrow, which drains north along the River Uinshin in a shallow valley known as “The Towery Plain” in southeast Sligo. The battle site is encircled by the Shee Lugh, Heapstown, Carrowkeel, and Keshcorran passage tombs [19]. The latter two reside in the Bricklieve Mountains and, due to their karstic formation, a complex and diffuse hydrological recharge cycles within the sinkholes, springs, relict caves, and small streams of the area [19]. The Celtic language scholar T.F. O’Rahilly argues that the Moytura hillscape and valley were the setting of a seminal battle in which the heroes of different mythological and Fenian cycles—Fionn, Lugh, and Cúchulainn—all slay a one-eyed monster, and were therefore variations of a sole Gaelic demi-god, unified by place of Moytura, rather than competing historical narratives [19].

3.2.2. Tobar na Súil (Well of the Eye): A Holy Well on Tullaghan Hill

South of Sligo’s Ballysadare Bay, between the eastern end of the Ox Mountains and the Slieveward Bog, rises Tullaghan Hill, one-thousand meters above sea level. Near its top, facing east, and marked by a cairn, is a holy well (Figure 6). In Topographia Hibernica, the Welsh priest and historian Giraldus Cambrensis described a fount “in Connacht on the top of a high mountain and some distance from the sea, which in any one day ebbs and overflows three times, imitating the ebbing and flowing of the sea” [29]. Wells such as the one on Tullaghan Hill were known as pilgrimage destinations for water cults and places of healing, from before the origins of the Gaelic Festival of Lughnasa to after the Christian conversion of Ireland, when wells were incorporated into the ecclesiastical calendar of the church as sites of veneration. Yeats once stated that the history of a nation was not revealed “in parliaments and battlefields but in what the people say to each other on fair-days and high days, and in how they farm and quarrel, and go on pilgrimage” [30]. The Gaelic name for natural wells is tobar na súil (well of the eye), suggesting that, in pre-Christian Ireland, the mouths of the wells gazed out over the landscape like a god or served as an entrance to the Celtic Otherworld [19]. A private local history published by Father O’Rorke in 1889 describes the cairn-well “as an eyrie on the face of a precipice, from which the hawks come whirling and screaming on the approach of an intruder,” illuminating the origin of the other name for the site on Tullaghan Hill: ‘Hawkswell’ [19]. This toponym echoes like a raptor’s cry in the title of Yeats’ experimental drama At the Hawk’s Well (1917) [31], which imagines Cúchulainn sailing into Ballysadare Bay and climbing the steep stony rise of Tullaghan Hill to drink the immortal waters of its holy fount. The American poet Ezra Pound, who worked briefly as a private secretary for Yeats, introduced him to translations of Japanese Noh dramas in 1913 [19]. Involving one-act plays, Noh actors performed in symbolic masks to small, initiated audiences [19].

Figure 6.

Sligo’s holy wells. (Upper Left): A.I.-generated image of W.B. Yeats’ drama At the Hawk’s Well. (Lower Left): Tullaghan Hill holy well. (Right): Location of Hawkswell (Tullaghan Well) and large-scale view and numerical breakdown of well clusters in County Sligo, which comprise 32% of all wells in the Republic of Ireland. Map by Charles Travis. Data Source: [11] and Sligo Heritage and Genealogy Centre [32]. Projection Geographic Coordinate System, Datum and Spheroid: WGS 1984.

Set on a stony hillside beside a barren well, guarded by a fierce hawk-woman, Yeats’ play opens with an Old Man who has waited fifty-years for the dry spring to rise so he can drink of its waters and gain immortality: “I call to the eye of the mind/A well long choked up and dry/And boughs long stripped by the wind,/And I call to the mind’s eye/Pallor of an ivory face,/Its lofty dissolute air,/A man climbing up to a place/The salt sea wind has swept bare” [31]. Learning of its power, the Irish demi-god Cúchulainn travels from his “ancient house beyond the sea” to the sacred well. The Old Man is alarmed and tells the younger man: “O, folly of youth,/Why should that hollow place fill up for you,/That will not fill for me?” [31]. But Cúchulainn, resolving to stay and wait for the waters to rise, tells the Old Man about a “great grey hawk swept down out of the sky,” flying “[a]s though it would have torn me with its beak/Or blinded me, smiting with that great wing” [31]. The Old Man informs Cúchulainn that the hawk is the Guardian of the Well: “The Woman of the Sidhe herself,/The mountain witch, the unappeasable shadow./She is always flitting upon this mountain-side,/To allure or to destroy” [31]. As the pair agree to share the well’s water, the Guardian of the Well throws off her cloak, fixes her raptor’s eyes upon Cúchulainn, and begins to shriek and dance, “moving like a hawk” [31]. As the demi-god’s battle rage begins to mount, water begins to bubble in well. The Guardian flees to call the warrior women of hills with Cúchulainn in pursuit. Unable to catch her, he returns, and the Old Man informs him that they have missed the rising waters. Furious, Cúchulainn rushes out to battle. The Musicians serving as the play’s chorus ruefully lament: “He has lost what may not be found/Till men heap his burial-mound/And all the history ends” [31]. The cairn still sits on the top of Tullaghan Hill, as history’s gyres form a spiral between the past, present, and back again from a summit where one travelling along the Wild Atlantic Way trek can spy the shoulder of the Ox Mountains to the west and the tides of Ballysadare Bay below, whose ebbs and flows still feed the waters of the sacred well.

4. Discussion

Heritage studies can benefit largely from the ubiquity of digital open-access and proprietary geospatial technology apps, software, and online data and the ability to digitize and geo-analyze archival materials and documents. GIS close reading practices mine digitized texts for information on location and associated phenomena, whilst distant reading methods—the remote sensing of texts—aggregate mined data through statistical and quantitative techniques to produce graphs, maps, and network trees, in order visualize and analyze spatial patterns occurring across genres and historical discourses within archival documents [33]. In turn, GIS deep mapping methods provide a stratigraphical historical lens through which to examine, collate, synthesize, format, visualize, and analyze qualitative and quantitative data. Such techniques integrate the physical locations of heritage sites, such as shipwrecks, archaeological monuments, and their associated climatological, weather, and environmental data, with the attributes of heritage sites mined from historical, literary, cultural, and other documents—which have not been traditionally employed to source geo-data—to produce richer and more holistic GIS layers that balance the “positivistic with the poetic” to visualize the palimpsestic and esoteric natures of heritage sites [34].

Such visualizations and analyses, based on database formatting techniques and methods, can facilitate more holistic and multi-dimensional perspectives of such sites to aid in their conservation and sustainability. They can also be employed to foster new, more sustainable, eco and cultural tourism initiatives and ways for tourists to read and cultivate “deeper” and more nuanced readings and appreciations of heritage landscapes. For instance, traditionally heritage climatology is framed as an applied, interdisciplinary field which examines how atmospheric conditions and weather affect the environments and material culture of existing heritage sites. In the case of the Spanish Armada, such methods can be employed to reframe wrecks sites along the WAW as “heritage climate sites” which foster public understanding of how atmospheric conditions and weather patterns contributed to a site’s creation, and can be employed in eco-tourism campaigns to promote the importance of understanding the impacts and effects of global climate change. Furthermore, because of the ill-fated 1588 Armada campaign, the Spanish navy lost at least 6000 men, with 4000 drowning on the Atlantic coasts of Ireland, leaving the “bones of Spanish sailors hidden under golden sand at Streedagh and Ballycroy and Rosbeg, wedged in rock and reef in the Rosses and the Blaskets and Lacada Point” [18] These sites, in part created by climatic conditions, offer “a silent yet eloquent monument to the lost enterprise of Philip II, King of Spain” [18]. More broadly the sites intimate the “Spectral Geography” of a mixed Iberian-Hibernian heritage that lingers along the west coast of Ireland, which can be juxtaposed with the archaeological landscape of tombs and holy wells that predominate County Sligo’s “Yeats Country.”

GIS deep map readings of the archaeological sites in County Sligo synchronized with the writings of the W.B. Yeats lessen both the abstract nature of scientific collation of tomb and holy well data as merely data points of coordinates and numbers, as well as the intangibilities of the poet’s often esoteric work. Tombs and wells in Sligo mapped in GIS with a geo-database refracted through a Yeatsian lens can frame these sites as repositories of “spectral” knowledge, memory, and cultural identity. In Ireland, many tombs and wells are regarded as metaphysical spaces where the boundaries between the esoteric and abstract (poetic, spiritual, emotional) and the material and concrete (physical landscape, archaeology, built environment) blur in the cultural imagination. The landscape imagery of Knocknarea, Hawkswell, Towery Plain, and other archaeological sites in Yeats’ work intimate how the stories and legends of supernatural beings he collected likely found their way into his symbolic language, enriching his poetic descriptions of archaeological sites and highlighting perceived relationships between natural and supernatural realms, but more significantly, the memories of a faded Gaelic culture that mark the spectral geographies of Sligo’s Yeats Country.

5. Conclusions

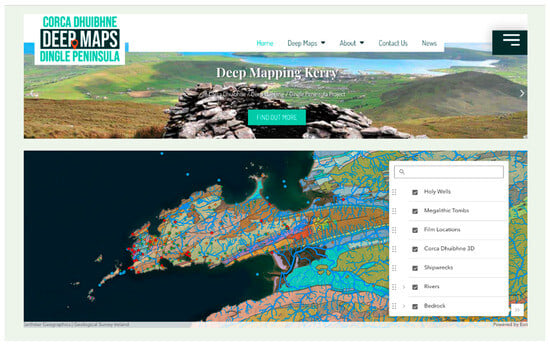

The Deep Mapping Kerry [35] project, based in Dingle, County Kerry, a town on the WAW, is an example of an local initiative that employs geospatial technology to engage in heritage promotion and sustainability to promote Corca Dhuibhne (the Dingle Peninsula) using methods conversant with ones discussed in this paper (Figure 7). To conclude, GIS deep mapping is a form of “remote sensing,” posited in Gunnar Olsson’s phrase as a “human activity located in the interface between poetry and painting” where “a satellite picture” is “a constellation of signs waiting to be transformed from meaningless indices into meaningful symbols … ” [36]. This paper’s GIS deep mapping of heritage sites on the WAW illustrates how “three key referencing systems—space, time and language-might be engineered in such a way that changes in one ripple into the others” [37]. Deep mappings of the contrasting historical climate landscapes of Spanish Armada wrecks framed by Edmund Spenser’s poetry and the ancient archaeology of “Yeats Country” in Sligo provide multidimensional perspectives on how esoteric and abstract forms of heritage—the archives of cultural knowledge and memory—are inextricably enmeshed with the physical identification, maintenance, and preservation of such heritage sites.

Figure 7.

Corca Dhuibhne deep maps, Deep Mapping Kerry (Léarscáiliú Chorca Dhuibhne) [35].

This paper has illustrated how, through the lens and bespoke formatting GIS databases, historical sites created by the confluences of human agency, atmospheric forces, and environmental factors can be framed as “heritage climate sites,” not only to ensure their sustainability, but as a means for such sites to serve as locations for public education that promote knowledge about how global climate change is inextricably tied to cultural, historical, and political factors. The “Spectral Geography” of Yeats Country is anchored in the stories and legends which the poet “excavated” from the region’s cultural landscapes imparting its natural and man-made features with agency and intention. The humanistic geographer Tuan notes that “storytelling seems to be the universal means of place-making. Stories of events- something significant or important has happened here- that have the power to transform object and area into place and landscape. What has happened may belong to the mythic past” [22]. Yeat’s poetic renderings of tombs and wells have imbued such sites with a sense of sacrality—an intangible element that plays a fundamental role in helping preserve Sligo’s archaeological landscapes where the presence of heritage sites—sustained by their spectral geographies, exist and are maintained by “the very conjuration and unsettling of presence, place, the present, and the past” [38].

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Texas, Arlington’s Charles T. McDowell Center for Global Studies Supplemental Faculty Research Grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is included in the article.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the Kerry Deep Map project at the Dingle Ireland Sacred Heart University Campus, the Trinity Centre for Environmental Humanities at Trinity College Dublin, the Dean’s Office of the College of Liberal Arts and the McDowell Center for Global Studies at the University of Texas, Arlington.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- O’Donohue, J. Anam Ċara; Random House: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wildatlanticway, The Wild Atlantic Way—Ireland’s Spectacular Coastal Route. 2025. Available online: https://www.thewildatlanticway.com/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Till, K.E. The New Berlin: Memory, Politics, Place; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2005; pp. 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne, G.; Sprince, E.; Griffin, K. The wild Atlantic way: A tourism journey. Ir. Geogr. 2020, 53, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiberd, D. Inventing Ireland: The Literature of the Modern Nation; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, R. Places on the Margin: Alternative Geographies of Modernity; Routledge: London, UK, 1991; pp. 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, E.E. The Personality of Ireland; The Lilliput Press: Dublin, Ireland, 1992; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. Bibliometric analysis of GIS applications in heritage studies based on Web of Science from 1994 to 2023. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollen, K.L. Deep Mapping and the Spatial Humanities: Representing Place in the Digital Age. Geohumanities 2018, 4, 567–582. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenhamer, D.J.; Corrigan, J.; Harris, T.M. (Eds.) Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2015; Volume 33, p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- National Monuments Service. 2024. Available online: https://www.archaeology.ie// (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Gregory, D. Pastoral, Postmodernity, and the Politics of Space. In Cultural Geography in Practice; Blunt, A., Ogborn, M., Eds.; Arnold: London, UK, 2003; pp. 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- McCormack, D.P. Remotely sensing affective afterlives: The spectral geographies of material remains. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2010, 100, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, H.H. The Weather of 1588 and the Spanish Armada. Weather 1988, 43, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, W.S. The Wrecks of the Spanish Armada on the Coast of Ireland. Geogr. J. 1906, 25, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, E. Virgils Gnat. prepared from Alexander, B. Grosart’s The Complete Works in Verse and Prose of Edmund Spenser [1882] by Risa, S. Bear at the University of Oregon. Grosart’s Text Is in the Public Domain. The University of Oregon, March 1996. Available online: https://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~rbear/gnat.html (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Spencer, E. The Faerie Qveene, Difpofed Into Twelve Books, Fashioning XII. Morall Vertues. London. Printed for VVilliam Ponfonbie. 1596. Available online: https://archive.org/details/faeriequeenedisp02spen (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Travis, C. Seachange: Early Modern Oceanic Wars, 1588–1762. In Environment as a Weapon. Historical Geography and Geosciences; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Travis, C. Ghost Seer of the West: W.B. Yeats and the Spectral Geographies of Sligo. In Sligo and Society: Interdisciplinary Essays on the History of an Irish County; Nolan, W., O’Connor, K., Eds.; Geography Publications: Dublin, Ireland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yeats, W.B. ‘Under Ben Bulben’, Poetry Foundation. 2024. Available online: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43298/under-ben-bulben (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Yeats, W.B. A Note on National Drama. Lit. Ideals Irel. 1899, 17, 418–422. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.F. Senses of Place. West. Folk. 1997, 56, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergh, S. Knocknarae: The ultimate monument, Megaliths and mountains in Neolithic Cúil Irra, north-west Ireland. In Monuments and Landscape in Atlantic Europein; Scarre, C., Ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2005; pp. 139–151. [Google Scholar]

- Yeats, W.B. The Black Tower. In The Collected Poems of W.B. Yeats; New Edition; Collier Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yeats, W.B. Project Gutenberg’s. In The Seven Woods: Being Poems Chiefly of the Irish Heroic Age; MacMillan: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1903. [Google Scholar]

- Yeats, W.B. The Wanderings of Oisin. In The Poems of W.B. Yeats, Volume Two: 1890–1898; McDonald, P., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yeats, W.B. The Wind Among the Reeds; Elkin Matthews: London, UK, 1899. [Google Scholar]

- Yeats, W.B. Mythologies; Scribner: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara, J.J., Translator; The First Version of the Topography of Ireland by Giraldus Cambrensis; Dundalgan Press: Dundalk, Ireland, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Yeats, W.B. William Carleton. In William Carleton, Stories from Carleton; W. J. Gage: New York, NY, USA, 1889; pp. ix–xvii. [Google Scholar]

- Yeats, W.B. At the Hawk’s Well. In Delphi Collected Poetical Works of W. B. Yeats, Kindle, ed.; (Illustrated) (Delphi Poets Series Book 7); Delphi Classics: East Sussex, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- County Sligo Heritage and Genealogy Centre. 2024. Available online: https://sligoroots.com/sligo-heritage-centre-office/ (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Moretti, F. Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary History; Verso: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Travis, C. Abstract Machine: Humanities GIS; Esri Press: Redlands, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Corca Dhuibhne Deep Maps. Deep Mapping Kerry (Léarscáiliú Chorca Dhuibhne) 2024. Available online: https://deepmapskerry.ie/ (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Olsson, G. Abysmal: A Critique of Cartographic Reason; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007; pp. 137–138. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenhamer, D.J.; Corrigan, J.; Harris, T.M. The Spatial Humanities: GIS and the Future of Humanities Scholarship; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- John, W. The spectral geographies of WG Sebald. Cult. Geogr. 2007, 14, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).