Public–Private Partnership for the Sustainable Development of Tourism Hospitality: Comparisons Between Italy and Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Public–Private Partnership in Heritage Management

2.2. Public–Private Partnership and Sustainable Tourism Development

2.3. Applications of Public–Private Partnership in Hospitality Tourism

2.4. Governance Models and Heritage Asset Management

2.5. Justification of the Case Studies’ Selection

3. Methodology

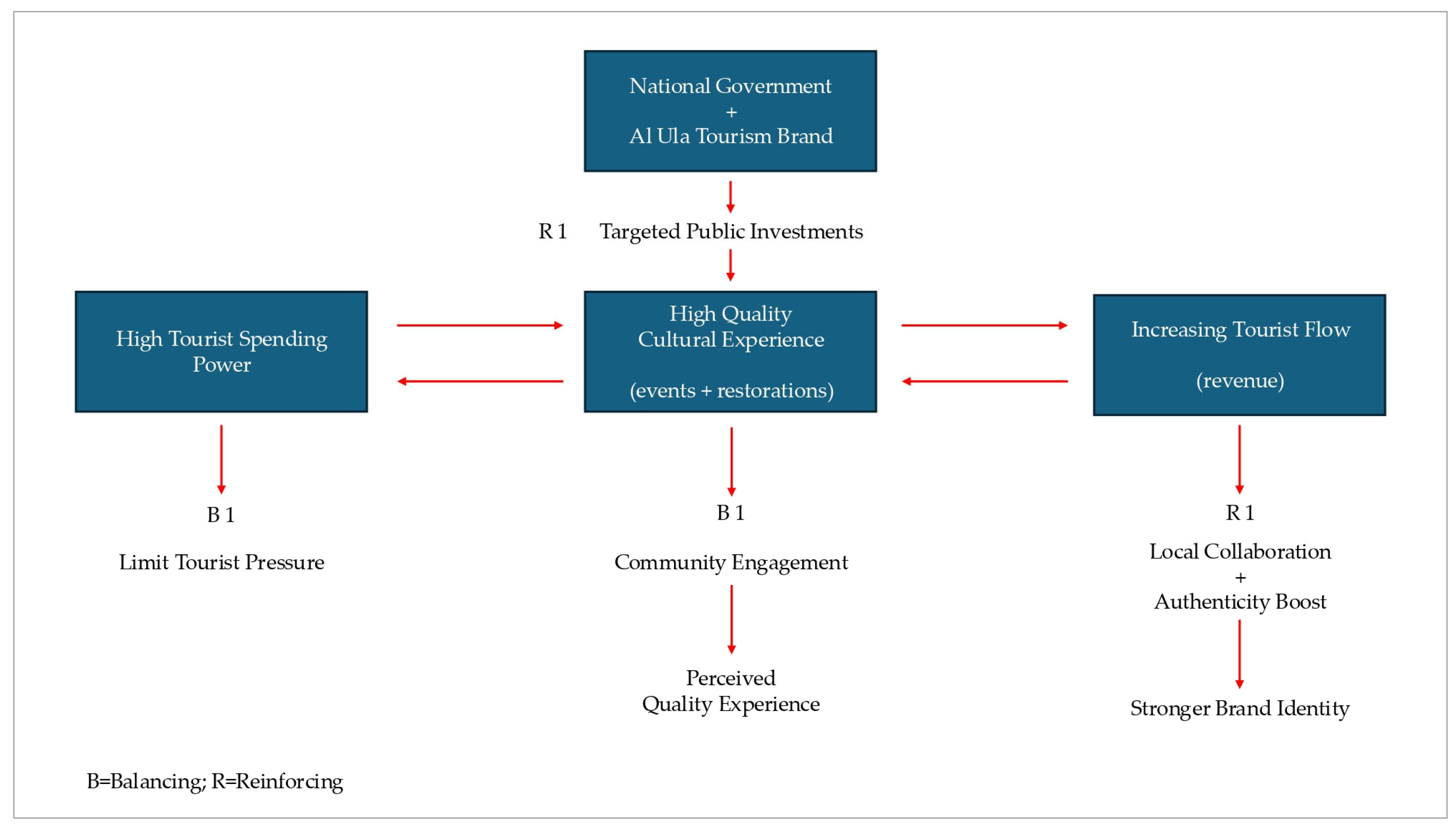

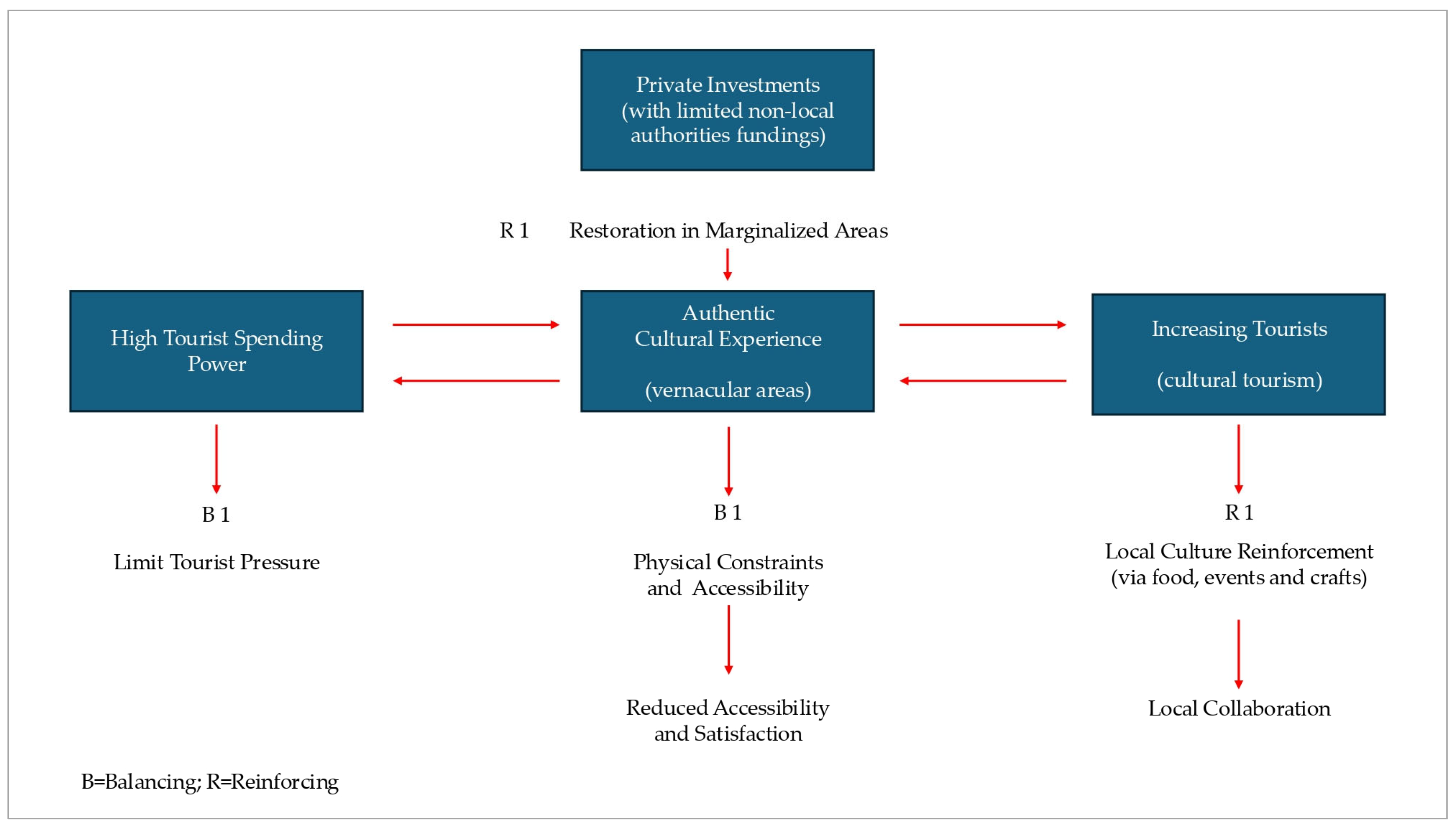

4. Results

4.1. Comparisons Between Architectural Interventions

4.1.1. Description of Dar Tantora

4.1.2. Description of Sextantio

5. Comparative Analysis

- Dar Tantora: Adaptive reuse, Najdi architecture, traditional materials (adobe, palm wood), passive design, cultural storytelling, public–private partnership, community engagement (training, employment), located near UNESCO site Hegra.

- Sextantio: Albergo diffuso model, troglodyte architecture, use of stone and plaster, low-impact restoration, cultural immersion, social enterprise model, UNESCO-listed Matera.

6. Discussion

Consumer Trends in Heritage Tourism

7. Conclusions

Policy Implications

8. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- How is public access to the hotel ensured for non-guests, and how is the general enjoyment of the heritage regulated?

- What specific actions has the hotel management taken to contribute to the protection of its tangible cultural heritage?

- Is the site subject to any national or local heritage protection laws? If so, how does this influence the hotel’s operations and responsibilities?

- How is the hotel’s heritage value promoted, and what strategies enhance its visibility?

- To what extent is the hotel integrated into regional or international tourism or cultural networks (e.g., hotel networks, associations, programs)?

- Has the hotel received public or private funding for conservation and/or promotion? If yes, under what schemes (e.g., grants, loans, sponsorship, tax incentives)?

- Are there ongoing financial incentives or tax benefits for maintaining and using the property as a heritage accommodation?

- Are there any agreements or partnerships with public institutions or private companies (e.g., cultural ministries, municipalities, sponsors or ambassadors) to manage or co-promote the hotel?

- How does the business model balance profitability with the duty to preserve and valorise the hotel’s cultural assets?

- Are there mechanisms in place to involve the local community in protecting, utilising, or promoting the hotel?

References

- Hodge, G.A.; Greve, C. Public–Private Partnerships: An International Performance Review. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellato, L.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Nygaard, C.A. Regenerative Tourism: A Conceptual Framework Leveraging Theory and Practice. Tour. Geogr. 2023, 25, 1026–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, P. The Routledge Research Companion to Heritage and Identity; Graham, B., Howard, P., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781315613031. [Google Scholar]

- UN Tourism. International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics 2008 (n. 83); UN Tourism: Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, R.W.; Goeldner, C.R. Tourism: Principles, Practices, Philosophies; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Liu, L.; Pan, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B. Tourism and Economic Growth: The Role of Institutional Quality. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 98, 103913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable Tourism Development: A Critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, L.; Olivera, M. On the Empirical Link between Tourism, Economic Growth and Energy Consumption: The Case of Uruguay. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2024, 16, 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Matesanz Gómez, D.; Segarra, V. On the Empirical Relationship between Tourism and Economic Growth. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, H.; Maqbool, S.; Tarique, M. The Relationship between Tourism and Economic Growth among BRICS Countries: A Panel Cointegration Analysis. Future Bus. J. 2021, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GÖKOVALI, U.; BAHAR, O. Contribution of Tourism to Economic Growth: A Panel Data Approach. Anatolia 2006, 17, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koodsela, W.; Dong, H.; Sukpatch, K. A Holistic Conceptual Framework into Practice-Based on Urban Tourism Toward Sustainable Development in Thailand. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkier, R.; Milojica, V.; Roblek, V. A Holistic Framework for the Development of a Sustainable Touristic Model. Int. J. Mark. Bus. Syst. 2015, 1, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, V.; Rusu, C.; Matus, N.; Botella, F. Tourist Experience Challenges: A Holistic Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovaird, T. Public–Private Partnerships: From Contested Concepts to Prevalent Practice. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2004, 70, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klijn, E.-H.; Teisman, G.R. Institutional and Strategic Barriers to Public—Private Partnership: An Analysis of Dutch Cases. Public Money Manag. 2003, 23, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žuvela, A.; Šveb Dragija, M.; Jelinčić, D.A. Partnerships in Heritage Governance and Management: Review Study of Public–Civil, Public–Private and Public–Private–Community Partnerships. Heritage 2023, 6, 6862–6880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruntland, G.H. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; UN: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Seraphin, H.; Gowreesunkar, V.G.B. Tourism: How to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals? Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2021, 13, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khizar, H.M.U.; Younas, A.; Kumar, S.; Akbar, A.; Poulova, P. The Progression of Sustainable Development Goals in Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review of Past Achievements and Future Promises. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Constructing Sustainable Tourism Development: The 2030 Agenda and the Managerial Ecology of Sustainable Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluk, K.A.; Cavaliere, C.T.; Higgins-Desbiolles, F. A Critical Framework for Interrogating the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 Agenda in Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanguay, G.A.; Rajaonson, J.; Therrien, M.-C. Sustainable Tourism Indicators: Selection Criteria for Policy Implementation and Scientific Recognition. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 862–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancas, F.J.; Lozano-Oyola, M.; González, M.; Caballero, R. Sustainable Tourism Composite Indicators: A Dynamic Evaluation to Manage Changes in Sustainability. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1403–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Torres-Delgado, A.; Crabolu, G.; Palomo Martinez, J.; Kantenbacher, J.; Miller, G. The Impact of Sustainable Tourism Indicators on Destination Competitiveness: The European Tourism Indicator System. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 1608–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glyptou, K. Operationalising Tourism Sustainability at the Destination Level: A Systems Thinking Approach Along the SDGs. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2024, 21, 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxas, F.M.Y.; Rivera, J.P.R.; Gutierrez, E.L.M. Framework for Creating Sustainable Tourism Using Systems Thinking. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camusa, S.; Hikkerovab, L.; Sahutc, J.M. Systemic Analysis and Model of Sustainable Tourism. Int. J. Bus. 2012, 17, 365–378. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G.; Torres-Delgado, A. Measuring Sustainable Tourism: A State of the Art Review of Sustainable Tourism Indicators. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter Sai, J.; Muzondo, N.; Marunda, E. Challenges Affecting Establishment and Sustainability of Tourism Public Private Partnerships in Zimbabwe. Asian Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Seki, K. A Study on the Process of Regional Tourism Management in Collaboration between Public and Private Sectors. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 179, 339–349. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, R.; Zhang, C. Performance Analysis of PPP Models in Rural Tourism Projects of Shandong Province Based on DEA and Super-DEA. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0312380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazón, A.M.; Moraleda, L.F. Public Private Cooperation in Tourism Destinations Promotion: The Methodology of Social Network Analysis. Cuadernos. Turismo. 2013, 31, 199–223. [Google Scholar]

- Beresecka, J.; Papcunova, V. Cooperation between Municipalities and the Private Sector in the Field of Tourism (Case Study). Sci. Pap. Univ. Pardubic. Ser. D Fac. Econ. Adm. 2020, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzan, A.; Correa-Jaramillo, J.; Jiménez-Zarco, A.I. Participation of Stakeholders in the Internationalization of the City of Medellin. J. Qual. Res. Tour. 2024, 5, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Matteis, F.; Notaristefano, G.; Bianchi, P. Public—Private Partnership Governance for Accessible Tourism in Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). Sustainability 2021, 13, 8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurkin Badurina, J.; Klapan, M.; Soldić Frleta, D. Stakeholders’ Collaboration in the Development of an Authentic Gastronomic Offering in Rural Areas: Example of the Ravni Kotari Region in Croatia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Hidalgo, I.; Pulido-Fernández, J.I. Examining the Organizational-Financial Structure of Public-Private Destination Management Organizations. In Smart Tourism as a Driver for Culture and Sustainability; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 543–562. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M.W. Innovation, Tourism and Destination Development: Dolnośląskie Case Study. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 1604–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Morales, O.; Álvarez-González, J.A.; Sanfiel-Fumero, M.Á.; Armas-Cruz, Y. Governance, Corporate Social Responsibility and Cooperation in Sustainable Tourist Destinations: The Case of the Island of Fuerteventura. Isl. Stud. J. 2016, 11, 561–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundelfinger, J. Benefits of Public–Private Cooperation: The Case Study of Seve Ballesteros-Santander Airport in Spain. J. Airpt. Manag. 2024, 18, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Lobato, A.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M.; Di-Clemente, E. La Gestión Público-Privada En La Red de Destinos de Los Itinerarios Culturales Del Consejo de Europa: La Ruta Del Emperador Carlos V. Rev. Galega Econ. 2021, 30, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkhanova, N.P. Public-Private Partnership as an Instrument for Regional Entrepreneurial Development. J. Adv. Res. Dyn. Control Syst. 2020, 12, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, T.P.; Zhang, C. Why Public–Private Cooperation Is Not Prevalent in National Parks within Centralised Countries. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 1109–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, N.E.; Darmohraj, A. Public-Private Collaboration in Tourism. Institutional Capacities in Local Tourism Management Partnerships in Argentina. Rev. CLAD Reforma Democr. 2016, 65, 157–192. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, C.; Pierdicca, R.; Paolanti, M.; Aleffi, C.; Tomasi, S.; Paviotti, G.; Passarini, P.; Mignani, C.; Ferrara, A.; Cavicchi, A. The Role of ICTs and Public-Private Cooperation for Cultural Heritage Tourism. The Case of Smart Marca. Capitale Cult. 2020, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruoss, E. Opportunities to Leverage World Heritage Sites for Local Development in the Alps. eco.mont (J. Prot. Mt. Areas Res.) 2015, 8, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.H.; Lee, J.; Yap, M.H.T.; Ineson, E.M. The Role of Stakeholder Collaboration in Culture-Led Urban Regeneration: A Case Study of the Gwangju Project, Korea. Cities 2015, 44, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrić, M.; Tomas Žiković, I.; Arbula Blecich, A. Profitability Determinants of Hotel Companies in Selected Mediterranean Countries. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraž. 2019, 32, 1977–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucharreira, P.R.; Antunes, M.G.; Abranja, N.; Justino, M.R.T.; Quirós, J.T. The Relevance of Tourism in Financial Sustainability of Hotels. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 25, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Martínez, A.M.; Santana-Talavera, A.; Parra-López, E. Destination Competitiveness Through the Lens of Tourist Spending: A Case Study of the Canary Islands. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louca, C. Income and Expenditure in Tourism Industry: Time Series Evidence from Cyprus. Tour. Econ. 2006, 12, 603–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, X.A.; Martínez-Roget, F.; Pawlowska, E. Academic Tourism: A More Sustainable Tourism. Reg. Sect. Econ. Stud. 2013, 13, 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.-H. The Response of Hotel Performance to International Tourism Development and Crisis Events. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; O’Neill, J.W.; Mattila, A.S. The Role of Hotel Owners: The Influence of Corporate Strategies on Hotel Performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Južnik Rotar, L.; Gričar, S.; Bojnec, Š. The Relationship between Tourism and Employment: Evidence from the Alps-Adriatic Country. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraž. 2023, 36, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, A. New Directions in the Growth of Tourism Employment?: Propositions of the 1980s. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 1992, 24, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan Pour Farashah, M.; Aslani, E.; Yadollahi, S.; Ghaderi, Z. Postoccupancy Evaluation of Historic Buildings after Their Adaptive Reuse into Boutique Hotels: An Experience from Yazd, Iran. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2023, 41, 849–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.C. Hip Heritage: The Boutique Hotel Business in Singapore. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 11, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hua, X. A 30-Year Controversy over the Shanghai East China Electric Power Building: The Creation and Conservation of Late 20th Century Chinese Architectural Heritage. Built Herit. 2021, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Kadir, S.; Jamaludin, M.; Awang, A.R. Accessibility Adaptation in the Design of Heritage Boutique Hotels: Malacca Case Studies. Environ.-Behav. Proc. J. 2020, 5, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, S.Y.; Aksah, H.; Ismail, E.D. Heritage Conservation and Regeneration of Historic Areas in Malaysia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 105, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piriyakul, I.; Piriyakul, R. Unveiling the Power of Storytelling and Co-design: Enhancing Customer Value in Cultural Boutique Hotels. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarantakou, E.; Tsamos, G.; Vlami, A.; Christidou, A.; Maniati, E. Factors of Authenticity: Exploring Santorini’s Heritage Hotels. Tour. Hosp. 2024, 5, 782–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginés-Ariza, P.; Noguer-Juncà, E.; Fusté-Forné, F. Local Perspectives of the Relationships between Food and Tourism in the City of Girona (Catalonia, Spain). Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Syst. 2024, 17, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, V.M.P.; da Costa Guerra, R.J.; Gonçalves, E.C.C. Cooperation Networks in Tourism and Hospitality: An Analysis Applied to Health and Wellness Tourism Product in Portugal. In Tourism Innovation in Spain and Portugal; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Adeola, O.; Ezenwafor, K. The Hospitality Business in Nigeria: Issues, Challenges and Opportunities. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2016, 8, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdymanapov, S.A.; Toxanova, A.N.; Galiyeva, A.H.; Abildina, A.S.; Aitkaliyeva, A.M. Development of Public-Private Partnership in the Republic of Kazakhstan. Int. Electron. J. Math. Educ. 2016, 11, 1113–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, T.; Aftab, F. Exploring Tourism’s Contribution to Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030: Aligning with UN SDG 8 for Sustainable Growth. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2025, 20, 1283–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, R.; Touati, M.S.E.; Alsharif, B.N. Determinants of Tourism in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Its Impact on Sustainable Development. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 32217–32228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampieri, S.; Bagader, M. Sustainable Tourism Development in Jeddah: Protecting Cultural Heritage While Promoting Travel Destination. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, L.D.; Mazzetto, S. Comparing AlUla and The Red Sea Saudi Arabia’s Giga Projects on Tourism towards a Sustainable Change in Destination Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampieri, S.; Saoualih, A.; Safaa, L.; de Carnero Calzada, F.M.; Ramazzotti, M.; Martínez-Peláez, A. Tourism Development through the Sense of UNESCO World Heritage: The Case of Hegra, Saudi Arabia. Heritage 2024, 7, 2195–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Romeedy, B.S.; Alharethi, T. Leveraging Green Human Resource Management for Sustainable Tourism and Hospitality: A Mediation Model for Enhancing Green Reputation. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscatelli, M. Heritage as a Driver of Sustainable Tourism Development: The Case Study of the Darb Zubaydah Hajj Pilgrimage Route. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshashai, D.; Leber, A.M.; Savage, J.D. Saudi Arabia Plans for Its Economic Future: Vision 2030, the National Transformation Plan and Saudi Fiscal Reform. Br. J. Middle East. Stud. 2020, 47, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.B.I.; Iqbal, S. Vision 2030 and the National Transformation Program. In Research, Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 146–166. [Google Scholar]

- GOV.SA. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Vision 2030. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Al Naim, M.A. Urban Transformation in the City of Riyadh: A Study of Plural Urban Identity. Open House Int. 2013, 38, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaim, M.M. The Hierarchical Order of Spaces in Arab Traditional Towns: The Case of Najd, Saudi Arabia. World J. Eng. Technol. 2020, 08, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaim, M.M. Discovering the Integrative Spatial and Physical Order in Traditional Arab Towns: A Study of Five Traditional Najdi Settlements of Saudi Arabia. J. Archit. Plan.-King Saud Univ. 2022, 34, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashary Alnaim, M.; Abdulfattah Bay, M. Regionalism Indicators and Assessment Approach of Recent Trends in Saudi Arabia’s Architecture: The Salmaniah Architectural Style and the King Salman Charter Initiatives as a Case Study. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, S. Fostering National Identity Through Sustainable Heritage Conservation: Ushaiger Village as a Model for Saudi Arabia. Heritage 2024, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, S.; Vanini, F. Urban Heritage in Saudi Arabia: Comparison and Assessment of Sustainable Reuses. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iswan; Khan, A.; Kadir, F.K.A.; Jabor, M.K.; Anis, S.N.M.; Zaman, K. Saudi Arabia’s Sustainable Tourism Development Model: New Empirical Insights. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2021, 71, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.; Stewart, M. Eco-Tourism and Luxury—The Case of Al Maha, Dubai. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Planning for Tourism: The Case of Dubai. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 2008, 5, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzetto, S. Sustainable Heritage Preservation to Improve the Tourism Offer in Saudi Arabia. Urban Plan 2022, 7, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscatelli, M. Rethinking the Heritage through a Modern and Contemporary Reinterpretation of Traditional Najd Architecture, Cultural Continuity in Riyadh. Buildings 2023, 13, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, P.; Capocchi, A.; Foroni, I.; Zenga, M. An Assessment of the Implementation of the European Tourism Indicator System for Sustainable Destinations in Italy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.D.; Yuksel, A.; Go, F. Heritage Tourism Destinations: Preservation, Communication and Development; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Xiong, K.; Liu, Z.; He, L. Research Progress and Knowledge System of World Heritage Tourism: A Bibliometric Analysis. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algassim, A. Favourable Sustainable Tourism Development in Al-Juhfa, Saudi Arabia. J. Assoc. Arab Univ. Tour. Hosp. 2021, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khoury, R.; Aouad, D.; Lteif, C. Beyond Materiality: Mud as a Living Material in Heritage Preservation. Front. Sustain. Cities 2025, 7, 1550496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwidar, S.; Abowardah, E. Internal Courtyards One of the Vocabularies of Residential Heritage Architecture and Its Importance in Building Contemporary National Identity. In Proceedings of the Nternational Architecture and Urban Studies Conference House & Home, Istanbul, Turkey, 3–4 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moussa, R.A. A Responsive Approach for Designing Shared Urban Spaces in Tourist Villages. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar Tantora Dar Tantora. Available online: https://dartantora.co/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Arab News Preserving the Past, Building the Future: Saudi Arabia’s Cultural Heritage and Business Synergy. 2024. Available online: https://www.arabnews.com/node/2578632/business-economy%20Arab%20NewsArab%20News%202Arab%20News%202Arab%20News%202 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Sextantio Sextantio. Available online: https://www.sextantio.it/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Gardetti, M.A.; Torres, A.L. Sustainability in Hospitality; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 9781351285360. [Google Scholar]

- Tani, M.; Papaluca, O. Local Resources to Compete in the Global Business. In Handbook of Research on Global Hospitality and Tourism Management; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2015; pp. 119–141. [Google Scholar]

- Di Gregorio, D. Place-Based Business Models for Resilient Local Economies. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2017, 11, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confalonieri, M. A Typical Italian Phenomenon: The “Albergo Diffuso”. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 685–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fissi, S.; Romolini, A.; Gori, E. Building a Business Model for a New Form of Hospitality: The Albergo Diffuso. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniccia, P.M.A.; Leoni, L. Co-Evolution in Tourism: The Case of Albergo Diffuso. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1216–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonić, B.; Stupar, A.; Kovač, V.; Sovilj, D.; Grujičić, A. Urban Regeneration through Cultural–Tourism Entrepreneurship Based on Albergo Diffuso Development: The Venac Historic Core in Sombor, Serbia. Land 2024, 13, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferwati, M.S.; El-Menshawy, S.; Mohamed, M.E.A.; Ferwati, S.; Al Nuami, F. Revitalising Abandoned Heritage Villages: The Case of Tinbak, Qatar. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2021, 7, 1973196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampiccoli, A.; Saayman, M.; Jugmohan, S. Are ‘Albergo Diffuso’ and Community-Based Tourism the Answers to Community Development in South Africa? Dev. S. Afr. 2016, 33, 548–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Hegra. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1293/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- UNESCO. The Sassi and the Park of the Rupestrian Churches of Matera. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/670/#:~:text=Outstanding%20Universal%20Value&text=Located%20in%20the%20southern%20Italian,natural%20caves%20of%20the%20Murgia (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Clauss-Balty, P.; Kanhoush, Y.; Ben Bader, S.; Charbonnier, J. Preliminary Analyses of Vernacular Earthen Architecture in the Gardens of Al-‘Ūla Oasis (Saudi Arabia). Proc. Semin. Arab. Stud. 2023, 52, 87–107. [Google Scholar]

- Rota, L. Matera. Storia Di Una Città; Giannatelli: Matera, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- al-Nasif, A. Al-’Ula (Saudi Arabia): A Report on a Historical and Archaeological Survey. Bull. (Br. Soc. Middle East. Stud.) 1981, 8, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthi, G.W. Tourism and Cultural Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia: The Case of Family Businesses in AlUla. J. Arab. Stud. 2024, 14, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losito, M.F. Sassi e Airbnb La Città Di Matera Fra Sviluppo e Designazione a Capitale Europea Della Cultura. 2022. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/104926642/Sassi_e_Airbnb_La_citt%C3%A0_di_Matera_fra_sviluppo_e_designazione_a_Capitale_Europea_della_Cultura (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Time Magazine Dar Tantora The House Hotel: World’s Greatest Places 2024. 2024. Available online: https://time.com/6992272/dar-tantora-2/ (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Palmer, D.; Dar Tantora by The House Hotel Announced in AlUla. Kerten Hospitality. Available online: https://kertenhospitality.com/dartantora-by-the-house-hotel-announced-in alula/ (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Ortile, M. Condé Nast Traveler. Available online: https://www.cntraveler.com/story/dar-tantora-hotel-alula-saudi-arabia (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- El-Khoury, R. Looking for the Liberal in the Neo-Liberal City [Alternative Public Spaces from Lebanon]. In Urban Challenges in the Globalizing Middle-East: Social Value of Public Spaces; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Legislative Decree Legislative Decree, 22 Gennaio 2004, n. 42. Codice Dei Beni Culturali e Del Paesa. 2004. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2004-02-24&atto.codiceRedazionale=004G0066 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

| Room Type | Description | Features | Estimated Price (EUR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dar Al Luban | Entry-level room | The traditional layout, natural ventilation, and candlelit ambience | 300–400 |

| Dar Al Bukhour | Enhanced room with lounge area | Additional seating space, traditional décor | 400–500 |

| Dar Al Hareer | Premium room with lounge and terrace | Private terrace with daybeds, panoramic views | 500–600 |

| Dar Al Oud | Two-bedroom suite | Ideal for families or groups, spacious living areas | 700–800 |

| Room Type | Description | Features | Estimated Price (EUR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classic Cave Room | Entry-level cave room | Original cave walls, minimalist furniture, and candlelit lighting | EUR250–EUR300 |

| Superior Cave Room | Enhanced room with expanded space | Rustic stone finishes, heated floors, and a large stone basin | EUR300–EUR400 |

| Suite Cave Room | Premium suite with added amenities | Larger footprint, soaking tub, panoramic Sassi views | EUR400–EUR500 |

| Executive Suite | Largest suite, ideal for long stays | Separate lounge, king bed, luxury tub, private entrance | EUR500–EUR600 |

| Principle | Dar Tantora (Al Ula, Saudi Arabia) | Sextantio (Matera, Italy) |

|---|---|---|

| Heritage Context | Traditional mudbrick buildings in a historic oasis town | Ancient cave dwellings (Sassi) in a UNESCO-listed rocky landscape |

| Architectural Style Preserved | Najdi vernacular architecture (mud, stone, wood) | Troglodyte cave architecture with medieval stone and wood features |

| Reuse Strategy | Adaptive reuse for boutique eco-hotel | Adaptive reuse into an albergo diffuso model |

| Restoration Approach | Minimal intervention, traditional techniques; emphasis on authenticity | Conservation-led; restoration with respect to original materials and form |

| Local Materials Used | Adobe, palm wood, local stone | Stone, wood, natural plaster |

| Community Involvement | Engagement through training and employment | Deep involvement in planning, service provision, and cultural interpretation |

| Integration with Urban Fabric | Reintegration of abandoned buildings within the historic core | Respectful insertion into the old city fabric; maintaining original street layouts |

| Environmental Sustainability | Passive design (natural ventilation and lighting); minimal energy use | Low-impact renovation; reuse of structures with minimal modern intervention |

| Cultural Continuity | Interiors reflect local heritage (design, crafts, storytelling) | Preservation of interior ambience; no addition of modern décor elements |

| Tourism Philosophy | Sustainable tourism is linked to cultural preservation and community benefits | Responsible tourism through cultural immersion and authenticity |

| Management Model | Public–private partnership with heritage preservation goals | Private initiative with a social enterprise model |

| UNESCO Connection | Located in Al Ula, near the UNESCO site Hegra | Located in the UNESCO-listed Matera |

| Economic and Legal Principles | Dar Tantora | Sextantio |

|---|---|---|

| Profitability | ~EUR15,000 daily revenue from room rentals at full occupancy (excl. extras); high-end heritage tourism model | ~EUR7000–EUR11,000/day estimated at full occupancy; boutique heritage hospitality model with stable revenue generation. |

| Number of tourists (annual) | Approx. 10,950 tourists/year (30 rooms × 365 days) | Approx. 6570 tourists/year (18 rooms × 365 days at full occupancy) |

| Capacity for spending (for tourists) | High-spending segment: ~EUR600 per night; excludes additional cultural/spa/dining expenses | Medium-to-high spending: ~EUR300–EUR600 per night per tourist, depending on room type and services. |

| Average stay (per night) | 1–2 nights (short cultural heritage stays are typical in Al Ula) | 2–3 nights (extended stays are common due to the immersive cultural experience in Matera) |

| Number of employees | Estimated 25–35 staff (incl. operations, maintenance, cultural programme staff, and community hires) | An estimated 20–30 staff (due to smaller scale; decentralised model) |

| Conservation | Conservation based on restoration; Focus on the balance between conservation and development Use of traditional building techniques RCU law on conservation | Conservation based on restoration; Focus on marginalised areas and vernacular, minor historical centres; Use of a non-invasive building technique Use of the legislative decree n. 42 2004 |

| Accessibility | Predominance of private-use buildings; Private buildings are accessible through organised tours and events for non-guest visitors Public areas are fully accessible | Predominance of private-use buildings; Private buildings are not accessible. Public spaces are fully accessible |

| Enhancement | Founding, collaboration, and facilitation from the Government (national); Collaboration with a local tourism brand; Collaboration with local artisans for the building restoration Tours; Participation in events and festival organisation; Prevalence of high-spending tourism | Private funding + public funding without the responsibility of the local land authorities; No sponsorship and local labels; Promotion of local cuisine and handicrafts; Prevalence of high-spending tourism with strategic low-cost offers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sampieri, S.; Mazzetto, S. Public–Private Partnership for the Sustainable Development of Tourism Hospitality: Comparisons Between Italy and Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156662

Sampieri S, Mazzetto S. Public–Private Partnership for the Sustainable Development of Tourism Hospitality: Comparisons Between Italy and Saudi Arabia. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156662

Chicago/Turabian StyleSampieri, Sara, and Silvia Mazzetto. 2025. "Public–Private Partnership for the Sustainable Development of Tourism Hospitality: Comparisons Between Italy and Saudi Arabia" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156662

APA StyleSampieri, S., & Mazzetto, S. (2025). Public–Private Partnership for the Sustainable Development of Tourism Hospitality: Comparisons Between Italy and Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 17(15), 6662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156662

_Li.png)