Sustainability in Purpose-Driven Businesses Operating in Cultural and Creative Industries: Insights from Consumers’ Perspectives on Società Benefit

Abstract

1. Introduction: The Role of Hybrid Managerial Models in a Changing Era

2. Theoretical Framework of the Research

2.1. Unveiling the B Movement Through an International Lens

2.2. Navigating Sustainability Orientation and CSR to Gain a Competitive Advantage

2.3. Beyond Cause-Related Marketing: Key Drivers and Challenges of Purpose-Oriented Business from a Consumer Perspective

3. Research Method

3.1. Research Setting

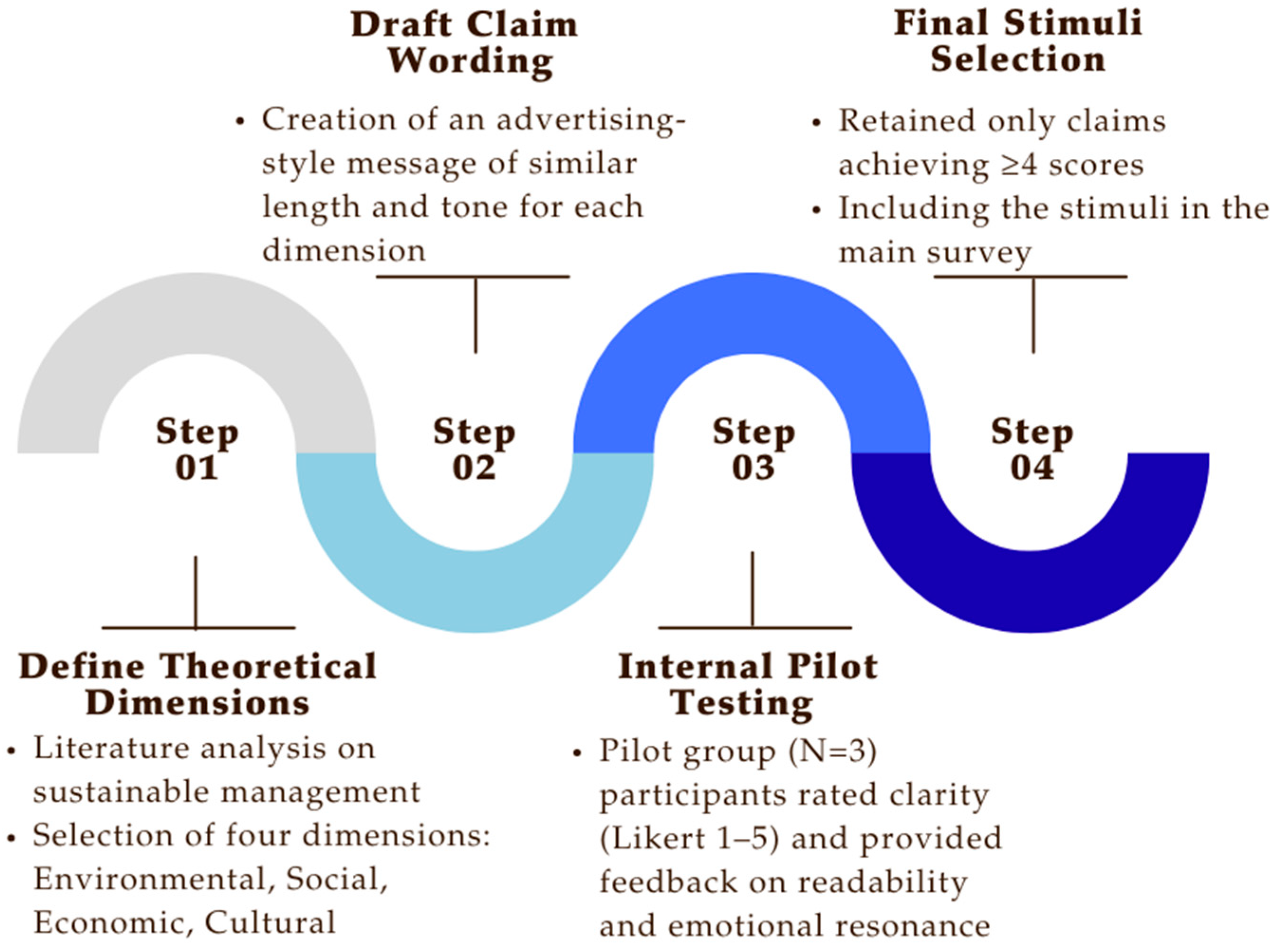

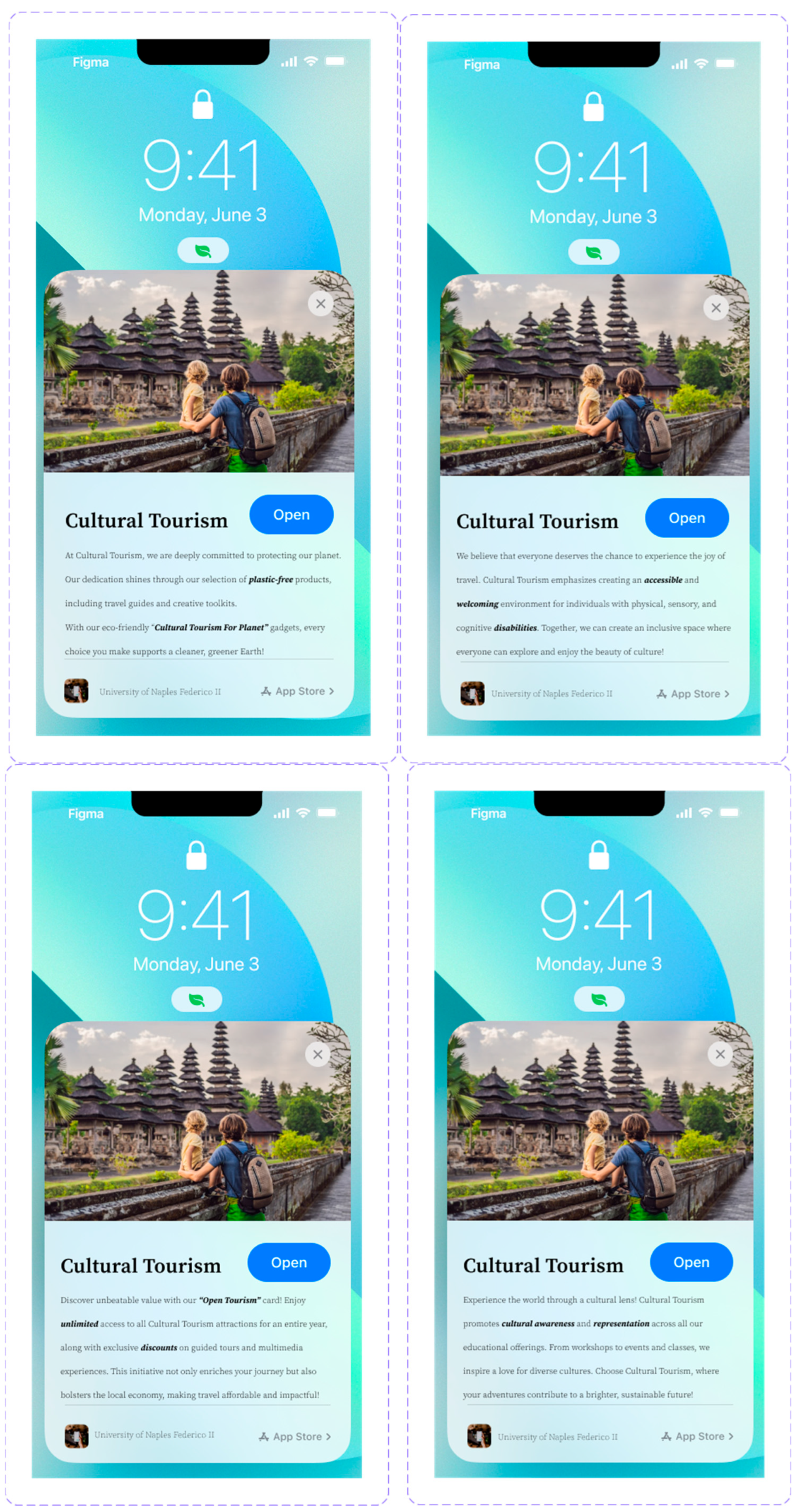

3.2. Research Design

4. Results

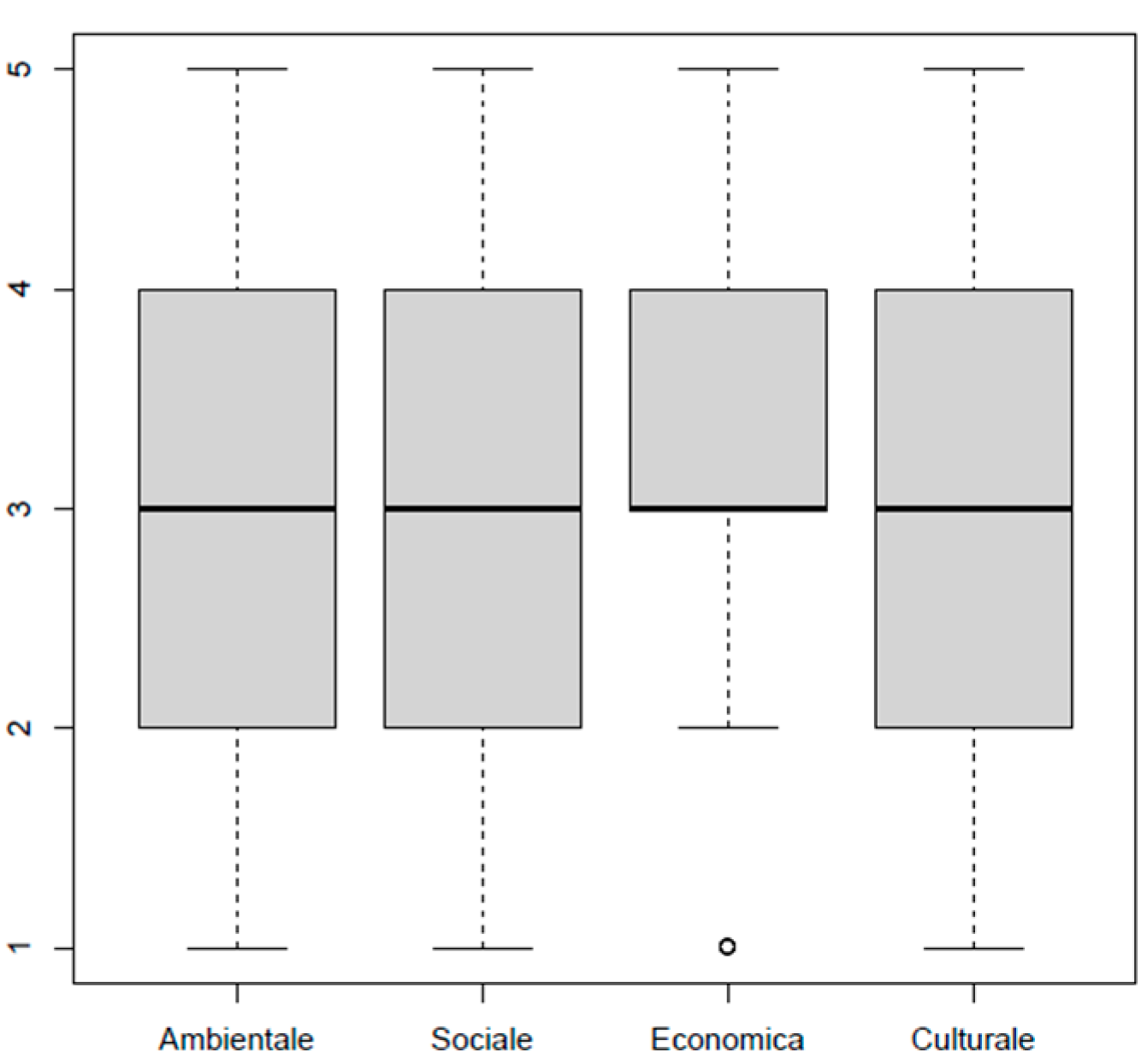

4.1. Perceptions of Sustainability Claims: A Quantitative Exploration

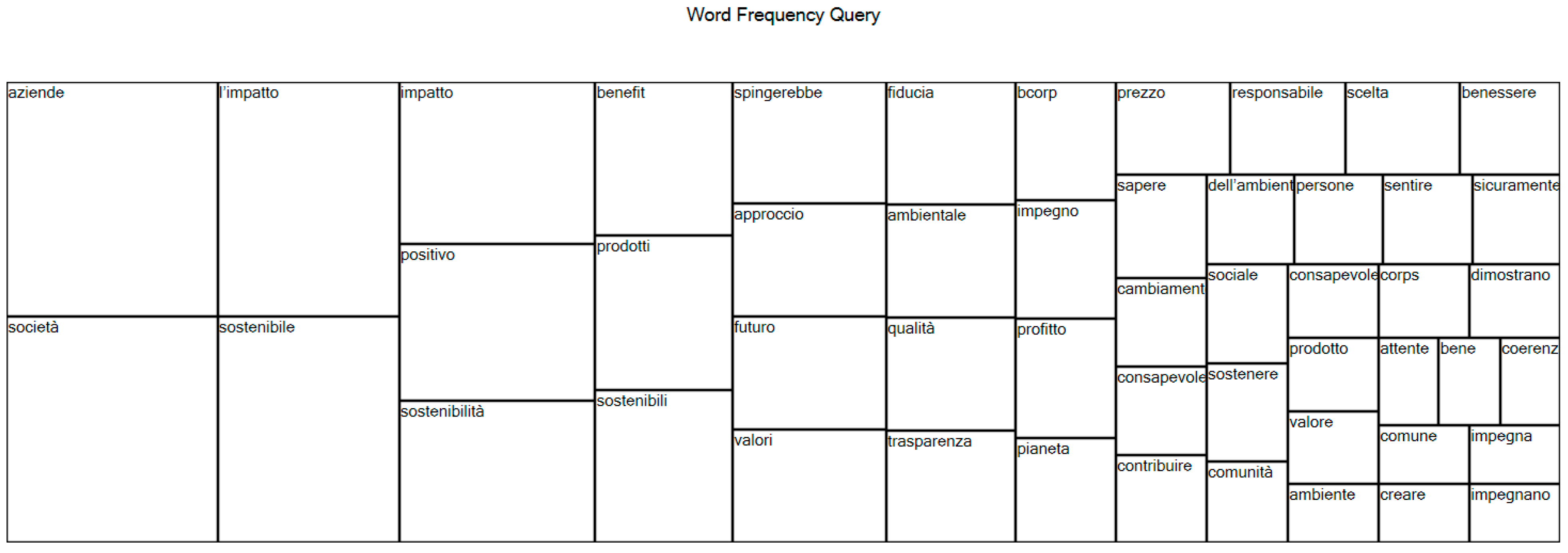

4.2. Motivational Drivers Behind Ethical Consumption

4.3. Motivational Patterns and Value Convergence in Choosing an SB

5. Implications and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fourth Sector Network. The Emerging Fourth Sector. 2009. Available online: http://www.fourthsector.net/learn/fourth- (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Sabeti, H. The Emerging Fourth Sector; Executive Summary; Aspen Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandrini, M. Towards a fourth sector?: Australian community organisations and the market. Third Sect. Rev. 2010, 16, 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Sabeti, H. The for-benefit enterprise. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- UN. United Nations Development Programme. The Fourth Sector: Can Business Unusual Deliver on the SDGs? UNDP. 2018. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/blog/2018/the-fourth-sector--can-business-unusual-deliver-on-the-sdgs.html (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Baudot, L.; Dillard, J.; Pencle, N. The emergence of benefit corporations: A cautionary tale. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2020, 67–68, 102073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinuany-Stern, Z.; Sherman, H.D. Operations research in the public sector and nonprofit organizations. Ann. Oper. Res. 2014, 221, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rask, M.; Mačiukaitė-Žvinienė, S.; Tauginienė, L.; Dikčius, V.; Matschoss, K.; Aarrevaara, T.; d’Andrea, L. Public Participation, Science and Society: Tools for Dynamic and Responsible Governance of Research and Innovation; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2018; p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Rask, M.; Puustinen, A.; Raisio, H. Understanding the Emerging Fourth Sector and Its Governance Implications. Scand. J. Public Adm. 2020, 24, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hota, P.K.; Subramanian, B.; Narayanamurthy, G. Mapping the intellectual structure of social entrepreneurship research: A citation/co-citation analysis. J. Bus. Ethic. 2020, 166, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroz, P.W.; Gamble, E.N. Business model innovation as a window into adaptive tensions: Five paths on the B Corp journey. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbo, J.; Langella, I.M.; Dao, V.T.; Haase, S.J. Breaking the ties that bind: From corporate sustainability to socially sustainable systems. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2014, 119, 175–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, C. The future of the corporation and the economics of purpose. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.; Cacciotti, G.; Cohen, B. The double-edged sword of purpose-driven behavior in sustainable venturing. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 149–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.C.; Slotegraaf, R.J.; Chandukala, S.R. Green claims and message frames: How green new products change brand attitude. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.; Wood, S. A “good” new brand—What happens when new brands try to stand out through corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 92, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaVoi, S.; Haley, E. How pro-social purpose agencies define themselves and their value: An emerging business model in the advertising-agency world. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2021, 42, 372–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zopounidis, C.; Lemonakis, C. The company of the future: Integrating sustainability, growth, and profitability in contemporary business models. Dev. Sustain. Econ. Financ. 2024, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternad, D.; Kennelly, J.J.; Bradley, F. Digging Deeper: How Purpose-Driven Enterprises Create Real Value; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gartenberg, C. Purpose-driven companies and sustainability. In Handbook on the Business of Sustainability; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 24–42. [Google Scholar]

- Rathee, S.; Milfeld, T. Sustainability advertising: Literature review and framework for future research. Int. J. Advert. 2024, 43, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maon, F.; Swaen, V.; De Roeck, K. Corporate branding and corporate social responsibility: Toward a multi-stakeholder interpretive perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Nascimento, J. Shaping a view on the influence of technologies on sustainable tourism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, N. Catalyzing Creative Tourism in Small Cities and Rural Areas in Portugal: The CREATOUR Approach. In Creative Tourism in Smaller Communities—Place, Culture, and Local Representation; Scherf, K., Ed.; University of Calgary Press: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2021; Chapter 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourzakarya, M. Searching for possible potentials of cultural and creative industries in rural tourism development; a case of Rudkhan Castle rural areas. Consum. Behav. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 17, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalfas, D.; Kalogiannidis, S.; Ambas, V.; Chatzitheodoridis, F. Contribution of the cultural and creative industries to regional development and revitalization: A European perspective. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crociata, A.; Pinate, A.C.; Urso, G. The cultural and creative economy in Italy: Spatial patterns in peripheral areas. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2025, 32, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, A.K. Selecting a within-or between-subject design for mediation: Validity, causality, and statistical power. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2023, 58, 616–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, N.; Kennedy, E.D.; Walker, J. Hybrid organizations as shape-shifters: Altering legal structure for strategic gain. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2015, 57, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iodice, G.; Bifulco, F. Benefit Corporations and the B Movement: Mapping the Research Landscape in Sustainable Management. Sustain. Responsible Manag. 2025, 6, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.D.; Marquis, C. Remaking capitalism: The movement for sustainable business and the future of the corporation. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 2897–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honeyman, R.; Jana, T. The B Corp Handbook: How You Can Use Business as a Force for Good; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gehman, J.; Grimes, M. Hidden badge of honor: How contextual distinctiveness affects category promotion among certified B corporations. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 2294–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, F.G.; Varon Garrido, M.A. Can profit and sustainability goals co-exist? New business models for hybrid firms. J. Bus. Strat. 2017, 38, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopaneva, I.M. Benefit Corporations in the U.S.: An Alternative Frame of Profit. Bus. Prof. Ethic. J. 2022, 41, 241–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sych, O.; Pasinovych, I. Hybrid business models as a response to the modern global challenges. Sci. Innov. 2021, 17, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Occhipinti, Z. Why Becoming a B Corp? A Discussion and Some Reflections. J. Mod. Account. Audit. 2023, 19, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringas-Fernández, V.; López-Gutiérrez, C.; Pérez, A. B-CORP certification and financial performance: A panel data analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.; Silva, V.; Sá, J.C.; Lima, V.; Santos, G.; Silva, R. B Corp versus ISO 9001 and 14001 certifications: Aligned, or alternative paths, towards sustainable development? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévêque, J.; Levillain, K.; Segrestin, B. Analyzing B Corp Certification: Opportunities and Complexities in Addressing Grand Challenges. In Managing with Purpose, Proceedings of the 85th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management (AOM 2025), 25–29 July 2025, Copenhagen, Denmark; HAL Open Science: Lyon, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Moroz, P.W.; Branzei, O.; Parker, S.C.; Gamble, E.N. Imprinting with purpose: Prosocial opportunities and B Corp certification. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantele, S.; Leardini, C.; Piubello Orsini, L. Impactful B corps: A configurational approach of organizational factors leading to high sustainability performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 1104–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigri, G.; Del Baldo, M.; Agulini, A. Governance and accountability models in Italian certified benefit corporations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2368–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirst, R.W.; Borchardt, M.; de Carvalho, M.N.M.; Pereira, G.M. Best of the world or better for the world? A systematic literature review on benefit corporations and certified B corporations contribution to sustainable development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1822–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, R. Benefit corporations at a crossroads: As lawyers weigh in, companies weigh their options. Bus. Horizons 2015, 58, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilburn, K.; Wilburn, R. Evaluating CSR accomplishments of founding certified B Corps. J. Glob. Responsib. 2015, 6, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levillain, K.; Segrestin, B. From primacy to purpose commitment: How emerging profit-with-purpose corporations open new corporate governance avenues. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzola, P.; Grechi, D.; Ossola, P.; Pavione, E. Certified Benefit Corporations as a new way to make sustainable business: The Italian example. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 1435–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mion, G.; Loza Adaui, C.R. Understanding the purpose of benefit corporations: An empirical study on the Italian case. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2020, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutheil, P.H. Social enterprises in Europe. Futuribles 2019, 429, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.societabenefit.net/ (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Nigri, G.; Del Baldo, M. Sustainability reporting and performance measurement systems: How do small-and medium-sized benefit corporations manage integration? Sustainability 2018, 10, 4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Baldo, M. Acting as a benefit corporation and a B Corp to responsibly pursue private and public benefits. The case of Paradisi Srl (Italy). Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabares, S. Do hybrid organizations contribute to sustainable development goals? Evidence from B Corps in Colombia. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paelman, V.; Van Cauwenberge, P.; Vander Bauwhede, H. The impact of B Corp certification on growth. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.C.; Dahlin, P. The impact of B Corp certification on financial stability: Evidence from a multi-country sample. Bus. Ethic. Environ. Responsib. 2022, 31, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, A.J.; Sacco, S. People, planet, profit: Benefit and B certified corporations-comprehension and outlook of business students. Acad. Bus. Res. J. 2017, 3, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Iodice, G.; Clemente, L.; Bifulco, F. Navigating Bcorp communications on social media. Insights from the Creative Industry. In Co-Creating Sustainable Solutions for Future-Proof Societies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK,; New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hosta, M.; Zabkar, V. Antecedents of environmentally and socially responsible sustainable consumer behavior. J. Bus. Ethic. 2021, 171, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Co-Operative Alliance (ICA). Sustainability Reporting for Co-Operatives: A Guidebook; ICA: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Soini, K.; Dessein, J. Culture-sustainability relation: Towards a conceptual framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. European environment policy for the circular economy: Implications for business and industry stakeholders. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1804–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Banks, G.; Hughes, E. The private sector and the SDGs: The need to move beyond ‘business as usual’. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 24, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Figge, F.; Aragón-Correa, J.A.; Sharma, S. Advancing research on corporate sustainability: Off to pastures new or back to the roots? Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 155–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Parhankangas, A.; Coupet, J.; Welch, E.; Barnum, D.T. Strategic decision making for the triple bottom line. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2016, 25, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, H.; Fichter, K.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Tiemann, I. Sustainability-oriented business model development: Principles, criteria and tools. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2018, 10, 256–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.; Mann, I.J.S.; Gullaiya, N. The role of organizational orientation and product attributes in performance for sustainability. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 122, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khizar, H.M.U.; Iqbal, M.J.; Rasheed, M.I. Business orientation and sustainable development: A systematic review of sustainability orientation literature and future research avenues. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 1001–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trizotto, R.C.A.; Nascimento, L.D.S.; da Silva, J.P.T.; Zawislak, P.A. Sustainability, business strategy and innovation: A thematic literature review. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2024, 15, 1338–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Levialdi, N.; Menichini, T. Integrating sustainability into strategic decision-making: A fuzzy AHP method for the selection of relevant sustainability issues. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 139, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Hörisch, J.; Freeman, R.E. Business cases for sustainability: A stakeholder theory perspective. Organ. Environ. 2019, 32, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, E.A.; Baum, M.; Huett, P.; Kabst, R. The contextual role of regulatory stakeholder pressure in proactive environmental strategies: An empirical test of competing theoretical perspectives. Organ. Environ. 2019, 32, 281–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abukari, K.; Musah, A.; Assaidi, A. The role of corporate sustainability and its consistency on firm financial performance: Canadian evidence. Account. Perspect. 2023, 22, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, U.; Sroufe, R.; Kraslawski, A. Creativity enables sustainable development: Supplier engagement as a boundary condition for the positive effect on green innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, S.; Jose, R. Addressing sustainability gaps. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 151208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermundsdottir, F.; Aspelund, A. Sustainability innovations and firm competitiveness: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Pascual, L.; Curado, C.; Galende, J. The triple bottom line on sustainable product innovation performance in SMEs: A mixed methods approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.K.; DeVereaux, C. A theoretical framework for sustaining culture: Culturally sustainable entrepreneurship. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 62, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suntikul, W. Cultural sustainability and fluidity in Bhutan’s traditional festivals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 2102–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecco, M.; Srakar, A. The unbearable sustainability of cultural heritage: An attempt to create an index of cultural heritage sustainability in conflict and war regions. J. Cult. Heritage 2018, 33, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, C.; Ferasso, M. The influence of a company’s inherent values on its sustainability: Evidence from a born-sustainable SME in the footwear industry. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2023, 9, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.M.J.; Che-Ha, N.; Alwi, S.F.S. Service customer orientation and social sustainability: The case of small medium enterprises. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajirasouli, A.; Kumarasuriyar, A. The social dimention of sustainability: Towards some definitions and analysis. J. Soc. Sci. Policy Implic. 2016, 4, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasson, J.; Wood, G. Urban regeneration and impact assessment for social sustainability. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2009, 27, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta, J.; Madrigal, L.; Pecorari, N. Social sustainability, poverty and income: An empirical exploration. J. Int. Dev. 2024, 36, 1789–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, P.; Cord, L.; Cuesta, J.; Espinoza, S.; Woolcock, M. Social Sustainability in Development: Meeting the Challenges of the 21st Century; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, J.; Loureiro, S.M.C. Mapping the sustainability branding field: Emerging trends and future directions. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2024, 33, 234–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Pretner, G.; Iovino, R.; Bianchi, G.; Tessitore, S.; Iraldo, F. Drivers to green consumption: A systematic review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 4826–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Sustainable development and sustainability. In Organisational Change Management for Sustainability; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, D.; Brettel, M.; Mauer, R. The three dimensions of sustainability: A delicate balancing act for entrepreneurs made more complex by stakeholder expectations. J. Bus. Ethic. 2020, 163, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunjra, A.I.; Bouri, E.; Azam, M.; Azam, R.I.; Dai, J. Economic growth and environmental sustainability in developing economies. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 70, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M. The sustainability pyramid: A hierarchical approach to greater sustainability and the United Nations sustainable development goals with implications for marketing theory, practice, and public policy. Australas. Mark. J. 2022, 30, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Ting, D.H.; Ng, W.K.; Chin, J.H.; Boo, W.-X.A. Why green products remain unfavorable despite being labelled environmentally-friendly? Contemp. Manag. Res. 2013, 9, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.X.; Siu, K.W.M. Challenges in food waste recycling in high-rise buildings and public design for sustainability: A case in Hong Kong. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 131, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, J. The Fourth Pillar of Sustainability: Culture’s Essential Role in Public Planning; Common Ground: Melbourne, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the scientific discourse on cultural sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, R.A.; Baracho, R.M.A.; Cantoni, L. The perception of UNESCO World Heritage Sites’ managers about concepts and elements of cultural sustainability in tourism. J. Cult. Heritage Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 14, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janhonen-Abruquah, H.; Topp, J.; Posti-Ahokas, H. Educating professionals for sustainable futures. Sustainability 2018, 10, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guccio, C.; Pignataro, G.; Rizzo, I. Evaluating the efficiency of public procurement contracts for cultural heritage conservation works in Italy. J. Cult. Econ. 2014, 38, 43–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catlin, J.R.; Luchs, M.G.; Phipps, M. Consumer perceptions of the social vs. environmental dimensions of sustainability. J. Consum. Policy 2017, 40, 245–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, K.; Guzman, F. How CSR reputation, sustainability signals, and country-of-origin sustainability reputation contribute to corporate brand performance: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, T.; Iqbal, S.; Ayub, A.; Fatima, T.; Rasool, Z. Promoting responsible sustainable consumer behavior through sustainability marketing: The boundary effects of corporate social responsibility and brand image. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo-Spena, T.; Tregua, M.; De Chiara, A. Trends and drivers in CSR disclosure: A focus on reporting practices in the automotive industry. J. Bus. Ethic. 2018, 151, 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergura, D.T.; Zerbini, C.; Luceri, B.; Palladino, R. Investigating sustainable consumption behaviors: A bibliometric analysis. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, I.; Chirico, A.; Ranalli, F. Corporate strategies oriented towards sustainable governance: Advantages, managerial practices and main challenges. J. Manag. Gov. 2022, 26, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, S.I.; Kusi-Sarpong, S. Identifying and exploring the relationship among the critical success factors of sustainability toward consumer behavior. J. Model. Manag. 2024, 19, 492–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doorn, J.; Risselada, H.; Verhoef, P.C. Does sustainability sell? The impact of sustainability claims on the success of national brands’ new product introductions. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 137, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Business Wire. Recent Study Reveals That More than a Third of Consumers Are Willing to Pay More for Sustainability as Demand Grows for Environmentally-Friendly Alternatives. 2021. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20211014005090/en/Recent-Study-Reveals-More-Thana-Third-of-Global-Consumers-Are-Willing-to-Pay-More-for-Sustainability-as-Demand-Grows-for-Environmentally-Friendly-Alternatives (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Xu, W.; Jin, X.; Fu, R. The influence of scarcity and popularity appeals on sustainable products. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1340–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.M.; Witmaier, A.; Ko, E. Sustainability and social media communication: How consumers respond to marketing efforts of luxury and non-luxury fashion brands. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majer, J.M.; Henscher, H.A.; Reuber, P.; Fischer-Kreer, D.; Fischer, D. The effects of visual sustainability labels on consumer perception and behavior: A systematic review of the empirical literature. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 33, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, F.; Föhl, U.; Walter, N.; Demmer, V. Green or social? An analysis of environmental and social sustainability advertising and its impact on brand personality, credibility and attitude. J. Brand Manag. 2021, 28, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Ng, A. Environmental and economic dimensions of sustainability and price effects on consumer responses. J. Bus. Ethic. 2011, 104, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; López-Sánchez, Y.; Carrillo-Hidalgo, I.; Durán-Román, J.L. Tourists’ meaning of sustainability as a tool for segmentation. A biosphere reserve case study. In Proceedings of the International Tourism Studies Association (ITSA) 2022 9th Biennial Conference: Corporate Entrepreneurship and Global Tourism Strategies After COVID-19, Gran Canaria, Spain, 24 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sfodera, F.; Cain, L.N.; Di Leo, A. Is technology everywhere? Exploring Generation Z’s perceptions of sustainable tourism in developing countries. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2024, 38, 28–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iodice, G.; Bifulco, F. Social entrepreneurship and value creation in the cultural sector. An empirical analysis using the multidimensional controlling model. Soc. Enterp. J. 2024, 21, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.Y.; Chuang, Y.J. Cultural sustainability: Teaching and design strategies for incorporating service design in religious heritage branding. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J. Cities of cultural heritage: Meaning, reappropriation and cultural sustainability in Eastern Lisbon riverside. J. Urban Reg. Anal. 2021, 13, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iodice, G.; Sergianni, C.; Tregua, M.; Bifulco, F. Shaping Value Propositions in Cultural Heritage from a PSL Perspective: The Case of Grassroots Museums. In Impacts of Museums on Global Communication; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 213–240. [Google Scholar]

- Iodice, G.; Bifulco, F. Le Società Benefit nel settore Culturale e Creativo: Mito o realtà? Rass. Econ. 2024, 1, 215–231. [Google Scholar]

- Zemite, I.; Kunda, I.; Judrupa, I. T The role of the cultural and creative industries in sustainable development of small cities in Latvia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charness, G.; Gneezy, U.; Kuhn, M.A. Experimental methods: Between-subject and within-subject design. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2012, 81, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoner, J.L.; Felix, R.; Stadler Blank, A. Best practices for implementing experimental research methods. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 1579–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alferes, V.R. Methods of Randomization in Experimental Design; Sage: London, UK, 2012; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Wedel, M.; Dong, C. A tutorial on the analysis of experiments using BANOVA. Psychol. Methods 2022, 27, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeretti, L.; Capone, F. Narrow or broad definition of cultural and creative industries: Evidence from Tuscany, Italy. Int. J. Cult. Creat. Ind. 2015, 2, 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaz, N.; Caldeira, E. The Interplay between Culture, Creativity, and Tourism in the Sustainable Development of Smaller Urban Centres. In Small Cities: Sustainability Studies in Community & Cultural Engagement; University of Calgary Press: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Henriques, C.H.; Elias, S.R. Interconnections between the cultural and creative industries and tourism: Challenges in four Ibero-American capital cities. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2022, 16, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, S.; Khalilpour, F.; Ashayeri, M.; Shabani, A. Handicrafts as cultural creative clusters: A spatial-cultural planning approach for the regeneration of the urban historical fabrics. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2024, 10, 1393–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadaki, E. Promoting green tourism synergies with cultural and creative industries: A case study of Greece. Sustainability 2024, 16, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crociata, A.; Pinate, A.C.; Urso, G. The Cultural and Creative Economy in Italy: Spatial Patterns in Peripheral Areas; Discussion Paper Series in Regional Science & Economic Geography, No. 2022-02; Gran Sasso Science Institute: L’Aquila, Italy, 2022; pp. 3–26. ISSN 2724-3680. [Google Scholar]

- Staiano, F. Designing and Prototyping Interfaces with Figma: Learn Essential UX/UI Design Principles by Creating Interactive Prototypes for Mobile, Tablet, and Desktop; Packt Publishing Ltd: Birmingham, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, M.; Naeem, M.; Shahzadi, M. Impact of branding on consumer buying behavior: An evidence of footwear industry of Punjab, Pakistan. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2017, 7, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti, L.; Caruana, A.; Snehota, I. The role of corporate social responsibility, perceived quality and corporate reputation on purchase intention: Implications for brand management. J. Brand Manag. 2012, 20, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, V.D.; Liu, X.; Yu, J.J. Mixed methods research in tourism and hospitality journals. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 1563–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teddlie, C.; Tashakkori, A. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences; Sage: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jafari-Sadeghi, V.; Mahdiraji, H.A.; Bresciani, S.; Pellicelli, A.C. Context-specific micro-foundations and successful SME internationalisation in emerging markets: A mixed-method analysis of managerial resources and dynamic capabilities. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curado, C.; Jesus, M.; Bontis, N. SMEs managers’ perceptions of MCS: A mixed methods approach. J. Small Bus. Strat. 2022, 32, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Lastres, B.; Wen, H.; Okumus, F. Exploring the impacts of internal crisis communication on tourism employees insights from a mixed-methods study. Tour. Manag. 2024, 100, 104796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajra, V.; Aggarwal, A. Unveiling the antecedents of senior citizens’ behavioural intentions to travel: A mixed-method approach. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2023, 23, 312–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femenia-Serra, F.; Ioannou, A.; Tussyadiah, I.P. Is smart scary? A mixed-methods study on privacy in smart tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 2212–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Azorín, J.F.; López-Gamero, M.D. Mixed methods studies in environmental management research: Prevalence, purposes and designs. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2016, 25, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, N.J.; Kleinman, K. Using R and RStudio for Data Management, Statistical Analysis, and Graphics; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Grömping, U. Using R and RStudio for data management, statistical analysis and graphics. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 68, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, B.W.; Sim, C.H. Comparisons of various types of normality tests. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2011, 81, 2141–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Estrada, E.; Cosmes, W. Shapiro–Wilk test for skew normal distributions based on data transformations. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2019, 89, 3258–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargha, A.; Delaney, H.D. The Kruskal-Wallis test and stochastic homogeneity. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 1998, 23, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Multiple significance tests: The Bonferroni method. BMJ 1995, 310, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wildemuth, B.M. Qualitative analysis of content. In Applications of Social Research Methods to Questions in Information and Library Science; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2009; Volume 308, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Odena, O. Using software to tell a trustworthy, convincing and useful story. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2013, 16, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.T.; Yeh, Y.Q.; Hsu, S.Y. Analysis of the effects of perceived value, price sensitivity, word-of-mouth, and customer satisfaction on repurchase intentions of safety shoes under the consideration of sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, P.S.; Balaji, M.S.; Jiang, Y. Greenfluencers as agents of social change: The effectiveness of sponsored messages in driving sustainable consumption. Eur. J. Mark. 2023, 57, 533–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsokiene, R.; Giedraitis, A.; Stasys, R. Visitor Perceptions Toward Sustainable and Resilient Tourism Destination: A Quantitative Assessment. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.M.F.; Costa, C.; Martins, F.; Pita, C. Is visitors’ future loyalty influenced by on-site experience intensity? Examining the mediating role of destination image and the moderating effect of visitors’ origin. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 38, 3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Sector | Second Sector | Third Sector | Fourth Sector | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Revenue | Taxes | Profit | Donations and Earnings | Earnings |

| Primary Purpose | Public Welfare | Private Wealth | Public Welfare | Public Welfare |

| Sustainability dimension | Environmental Sustainability | At Cultural Tourism, we are deeply committed to protecting our planet. Our dedication shines through our selection of plastic-free products, including travel guides, creative toolkits, and engaging games. With our eco-friendly “Cultural Tourism For Planet” gadgets, every choice you make supports a cleaner, greener Earth! |

| Social Sustainability | We believe that everyone deserves the chance to experience the joy of travel. Cultural Tourism emphasizes creating an accessible and welcoming environment for individuals with physical, sensory, and cognitive disabilities. Together, we can create an inclusive space where all can explore and enjoy the beauty of culture. | |

| Economic Sustainability | Discover unbeatable value with our “Open Tourism” card! Enjoy unlimited access to all Cultural Tourism attractions for an entire year, along with exclusive discounts on guided tours and multimedia experiences. This initiative not only enriches your journey but also bolsters the local economy, making travel both affordable and impactful. | |

| Cultural Sustainability | Experience the world through a cultural lens! Cultural Tourism takes pride in promoting cultural awareness and representation across all our educational offerings. From workshops to events and classes for children, we inspire a love for diverse cultures, ensuring a legacy of appreciation for generations to come. Choose Cultural Tourism for your travels, where every adventure contributes to a brighter, more sustainable future. |

| Option | Count | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 96 | 55% |

| Male | 79 | 45% | |

| 100% | |||

| Age | 17–25 | 77 | 44% |

| 26–35 | 23 | 13% | |

| 36–45 | 15 | 9% | |

| 46–55 | 54 | 31% | |

| >65 | 6 | 3% | |

| 100% | |||

| Education | Below a bachelor’s degree | 127 | 73% |

| Bachelor | 23 | 13% | |

| Master | 22 | 12% | |

| Doctorate | 3 | 2% | |

| 100% | |||

| Frequency of purchasing sustainable services/products | Rarely | 46 | 26% |

| Occasionally | 68 | 39% | |

| Periodically | 35 | 20% | |

| Quite often | 26 | 15% | |

| 100% | |||

| Willingness to pay a surcharge for sustainable services/products | Yes | 99 | 57% |

| No | 76 | 43% | |

| 100% |

| Slogan | W | p-Value | Normality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | 0.8907 | 6.22 × 10−10 | No |

| Social | 0.9150 | 1.88 × 10−8 | No |

| Economic | 0.9032 | 3.37 × 10−9 | No |

| Cultural | 0.9103 | 9.28 × 10−9 | No |

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Chi-squared (H) | 14.793 |

| Degrees of Freedom | 3 |

| p-value | 0.0020 |

| Comparison | p-adj | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental–Cultural | 1.0000 | No |

| Environmental–Economic | 0.0020 | Yes |

| Cultural–Economic | 0.0164 | Yes |

| Environmental–Social | 0.9174 | No |

| Cultural–Social | 1.0000 | No |

| Economic–Social | 0.1863 | No |

| Environmental Dimension | Weighted Percentage (%) | Social Dimension | Weighted Percentage (%) | Economic Dimension | Weighted Percentage (%) | Cultural Dimension | Weighted Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic | 2.26 | Inclusive | 3.09 | Discounts | 2.01 | Sustainable | 2.20 |

| Products | 2.26 | Disability | 1.93 | Tourism | 1.84 | Enrich | 1.10 |

| Important | 1.81 | Accessibility | 1.54 | Offer | 1.68 | Engaging | 1.10 |

| Creative | 1.36 | Sustainability | 1.54 | Experiences | 1.01 | Communicate | 1.10 |

| Cultural | 1.36 | Theme | 1.54 | Local | 1.01 | Community | 1.10 |

| Free | 1.36 | Everyone | 1.54 | Impact | 0.84 | Awareness | 1.10 |

| World | 1.36 | Inclusion | 1.16 | Activity | 0.67 | Contribute | 1.10 |

| Planet | 1.36 | People | 1.16 | Cultural | 0.67 | Cultural | 1.10 |

| Plastic | 1.36 | Attention | 0.77 | Unlimited | 0.67 | Culture | 1.10 |

| Sustainability | 1.36 | Center | 0.77 | Access | 0.67 | Person | 1.10 |

| Tourism | 1.36 | Culture | 0.77 | People | 0.67 | Different | 1.10 |

| Travel | 1.36 | Important | 0.77 | Positive | 0.67 | Educative | 1.10 |

| Business | 0.90 | Inclusion | 0.77 | Found | 0.67 | Efficient | 1.10 |

| Damage | 0.90 | Inclusivity | 0.77 | Advantages | 0.67 | Experiences | 1.10 |

| Ecological | 0.90 | Message | 0.77 | Travel | 0.67 | Express | 1.10 |

| Evidence | 0.90 | Values | 0.77 | Access | 0.50 | Events | 1.10 |

| Encourages | 0.90 | Travel | 0.77 | Practical | 0.50 | Easy | 1.10 |

| Environment | 0.90 | Attractive | 0.39 | Cultural | 0.50 | Future | 1.10 |

| People | 0.90 | Suitable | 0.39 | Locals | 0.50 | Impact | 1.10 |

| Reduce | 0.90 | Face | 0.39 | Experience | 0.50 | Recorded | 1.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iodice, G.; Bifulco, F. Sustainability in Purpose-Driven Businesses Operating in Cultural and Creative Industries: Insights from Consumers’ Perspectives on Società Benefit. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157117

Iodice G, Bifulco F. Sustainability in Purpose-Driven Businesses Operating in Cultural and Creative Industries: Insights from Consumers’ Perspectives on Società Benefit. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):7117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157117

Chicago/Turabian StyleIodice, Gesualda, and Francesco Bifulco. 2025. "Sustainability in Purpose-Driven Businesses Operating in Cultural and Creative Industries: Insights from Consumers’ Perspectives on Società Benefit" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 7117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157117

APA StyleIodice, G., & Bifulco, F. (2025). Sustainability in Purpose-Driven Businesses Operating in Cultural and Creative Industries: Insights from Consumers’ Perspectives on Società Benefit. Sustainability, 17(15), 7117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157117