Shared Producer Responsibility for Sustainable Packaging in FMCG: The Convergence of SDGs, ESG Reporting, and Stakeholder Engagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the primary drivers, challenges, and opportunities shaping the adoption of sustainable packaging in the FMCG industry, and what role do different stakeholders play?

- How do leading FMCG and packaging companies currently report on their sustainability performance, and what inconsistencies exist in their ESG reporting practices?

- How can stakeholder collaboration and corporate reporting be enhanced to accelerate the transition toward a more sustainable packaging ecosystem?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Sustainable Packaging in the FMCG Industry

2.2. SDGs and Packaging

2.3. Sustainability Reporting and Packaging

2.4. Stakeholder Influence in Sustainable Packaging

3. Methodology

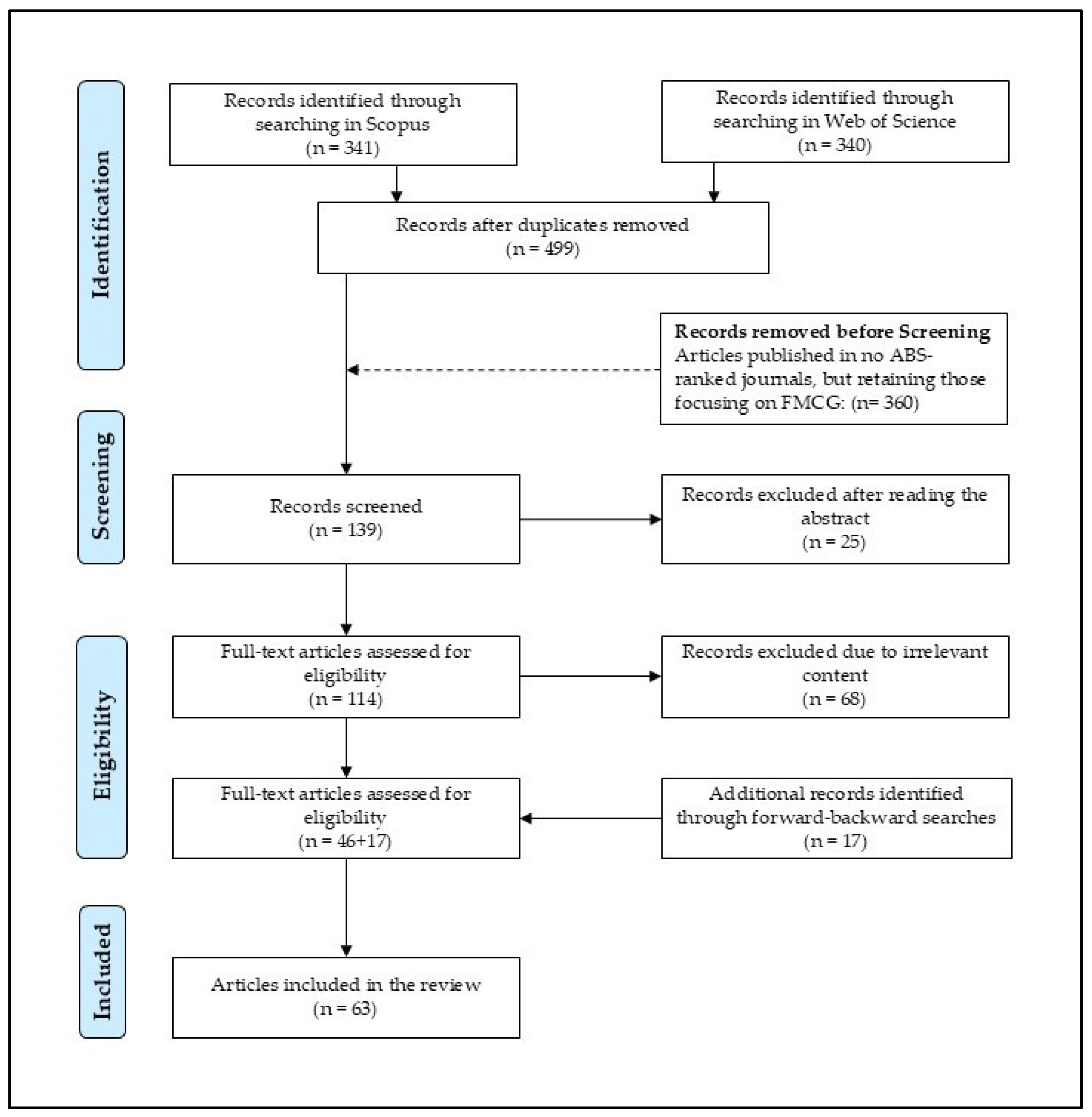

3.1. The Systematic Literature Review

3.1.1. Identification Stage

3.1.2. Screening Stage

3.1.3. Eligibility Stage

3.1.4. Inclusion Stage

3.2. Selection of Companies and Sustainability Reports

3.2.1. Packaging Companies

3.2.2. FMCG Companies

4. Findings

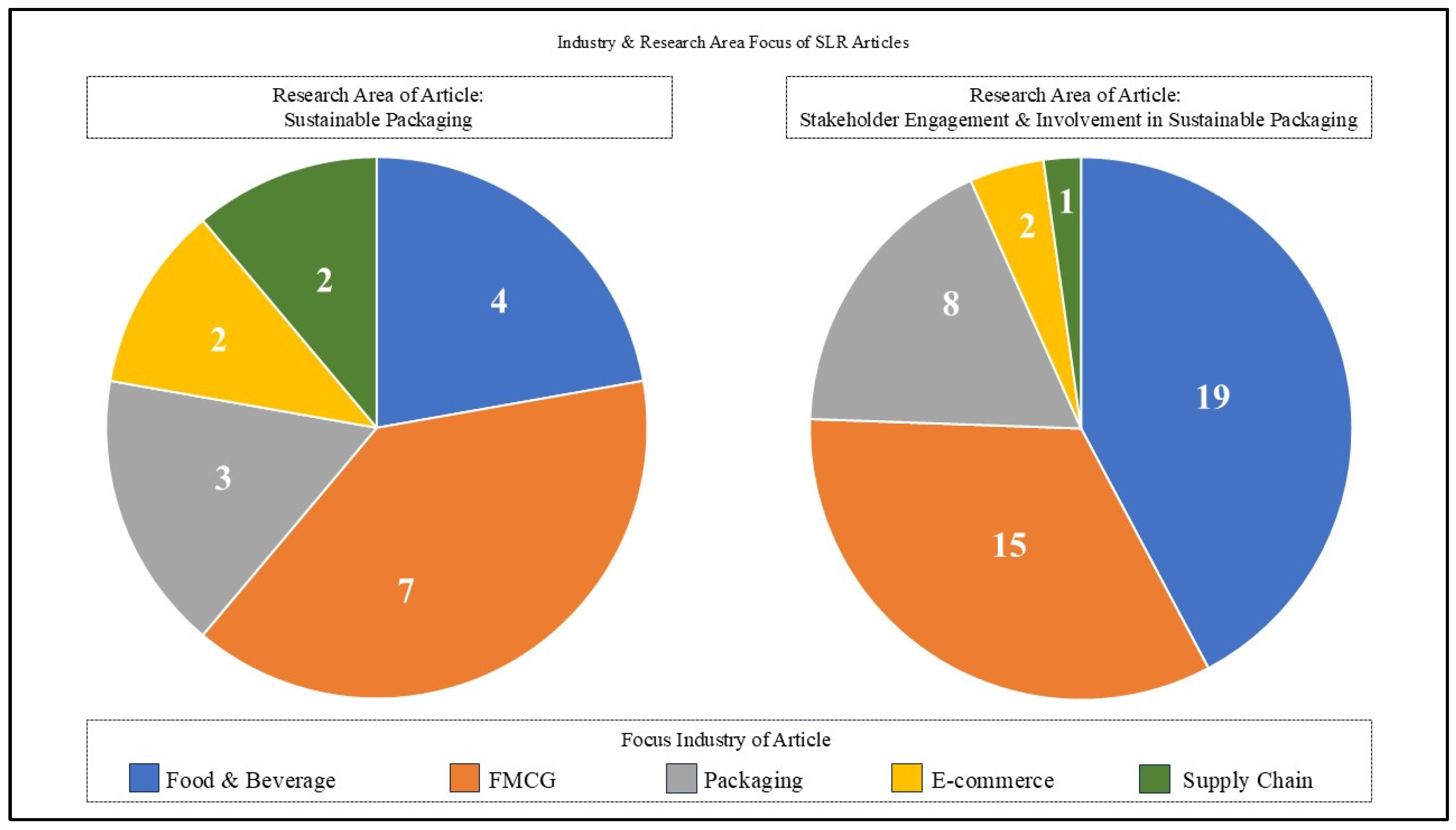

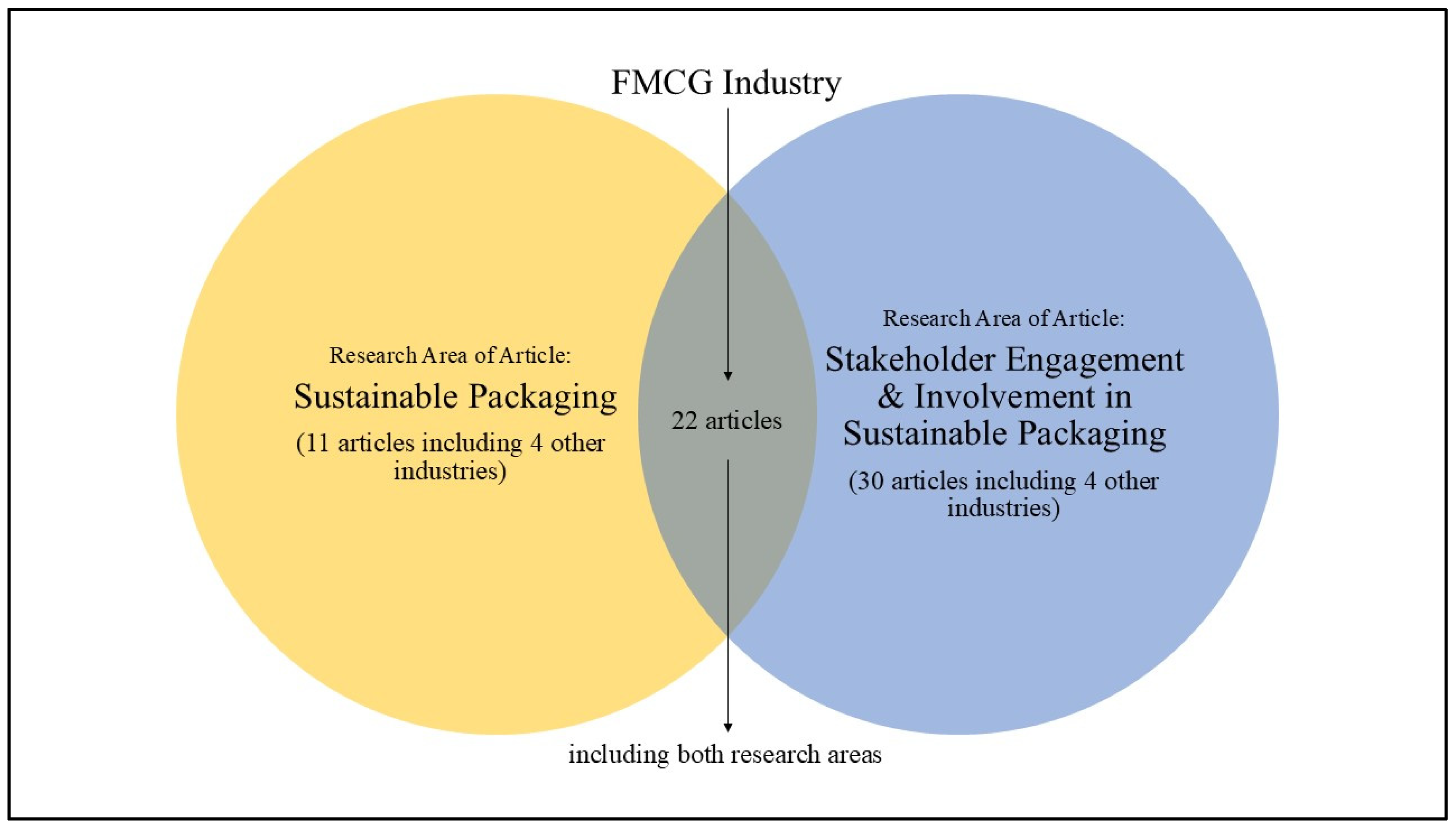

4.1. Insights from the SLR

4.1.1. Sustainable Packaging and Stakeholder Engagement in the FMCG Sector

4.1.2. Involvement of Stakeholders in Sustainable Packaging

4.1.3. General Trends and Themes in Sustainable Packaging

4.2. Insights from Sustainability (ESG) Reporting

Analysis of E, S, and G Indicators

4.3. Convergence of SDGs with Sustainable Packaging

5. Discussion and Recommendations

5.1. Interpreting the Key Themes in Sustainable Packaging Literature

5.2. From Disclosure to Accountability: A Discussion on Corporate ESG Reporting Practices

5.3. SDGs as a Framework for Sustainable Packaging

5.4. Stakeholder Synergies and Transition to Sustainable Packaging

5.5. Gaps and Issues Identified from the Data

5.6. Suggestions and Recommendations

5.6.1. A Conceptual Framework for Accelerated Transition Towards Sustainable Packaging

- Collaborative Product Design—FMCG companies and packaging manufacturers should work collaboratively on product design for FMCG companies to create environmentally friendly, cost-effective designs that satisfy consumer demands while at the same time engaging stakeholders in decision-making processes and sharing knowledge to address stakeholder pressure [27]. As one example of cooperation, packaging manufacturers could work alongside FMCG firms to produce packaging made of recycled material to reduce environmental impacts while meeting company packaging requirements [27].

- Consumer Education and Engagement—Educating and engaging consumers about the environmental effects of packaging materials and benefits of sustainable packaging can drive demand for it and convince FMCG companies and packaging manufacturers to adopt sustainable packaging solutions [123]. An FMCG company could launch an advertising campaign about its new sustainable packaging, not just print it on the packaging while encouraging customers to recycle it.

- Clear Labelling and Certification—Labelling and certification of sustainable packaging materials can assist consumers in making informed choices while driving demand for eco-friendly alternatives [123]. A packaging manufacturer could obtain certification of its sustainable materials from an official certification body; an FMCG company might clearly label its products as packaged with certified sustainable material packaging.

- Incentives for Sustainable Packaging—Regulators should incentivise FMCG companies and packaging manufacturers who implement sustainable packaging practices, including tax breaks, grants, or subsidies. A government could, for instance, grant tax breaks to companies who utilise at least 51% recycled content in their packaging products.

- Regulations and Standards—Regulators must implement and enforce regulations and standards related to sustainable packaging, including requirements for using recyclable or recovered materials in packaging, restricting their usage or providing guidance as to its environmental footprint. For instance, governments could make regulations mandating that all packaging be either recyclable or compostable by a certain date (for instance, an ordinance passed by local council could create such requirements).

- Supply Chain Collaboration—FMCG companies, packaging manufacturers, and other stakeholders in their supply chains should work collaboratively to promote sustainable packaging materials and practices. This involves sharing knowledge and best practices; working to reduce environmental impacts associated with packaging; and investing jointly in research and development of sustainable packaging solutions [27]. For instance, an FMCG could collaborate with its suppliers to establish an automated collection and recycling system of old packaging material (e.g., an FMCG could create an FMCG company–supplier partnership), etc.

5.6.2. Suggestions on Reporting Practices

- a.

- Combined Reporting

- b.

- Standardised Reporting Structure

5.6.3. Shared Producer Responsibility

- Shared Knowledge and Technological Innovation—FMCG firms bring a deep understanding of consumer behaviour and market conditions, while packaging manufacturers possess technical expertise in materials science and circular design. Joint responsibility under SPR creates the collaborative governance structure needed to merge these knowledge domains. This synergy is critical for developing and scaling complex technologies such as advanced chemical recycling, compostable bioplastics, or smart packaging embedded with IoT sensors for traceability. The shared financial and operational responsibility incentivises joint investment in these capital-intensive technologies, which might be too risky for a single entity to pursue alone, thereby aligning with SDG 9 (industry, innovation, and infrastructure) and SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production).

- Cost Sharing for Systemic Feasibility—Sustainable packaging implementation is often hindered by significant cost burdens. A distributed cost-sharing model, in which both FMCG companies and packaging suppliers share financial responsibility for recycling infrastructure, EPR compliance fees, and R&D for circular design, makes the adoption of advanced solutions more feasible. By aligning financial incentives and spreading costs, SPR reduces resistance and supports the long-term operational planning required for systemic change. Governments, in turn, can facilitate this through ESG-aligned incentives such as green tax credits or recovery subsidies.

- Enhanced Lifecycle Tracking through Data Analytics—SPR strengthens environmental reporting by creating a clear incentive for data transparency and traceability. Joint accountability necessitates investment in advanced data analytics, IoT, and blockchain technologies to track materials, emissions, and consumer disposal behaviour in real time. This moves beyond static annual ESG disclosures to dynamic, verifiable data streams that can support predictive models for waste management and meet the rigorous transparency requirements of frameworks like GRI, SASB, and TCFD more accurately.

- Driving Behavioural Change through Coordinated Engagement—The “say-do” gap in consumer behaviour is a major barrier to sustainability. SPR provides a framework for stakeholders to move beyond isolated marketing campaigns and jointly fund and execute coordinated educational initiatives informed by behavioural science. By sharing responsibility, companies, regulators, and retailers can co-design programs that use nudges, incentives, and clear communication to foster durable habits around reuse, proper sorting, and waste reduction, making sustainable choices easier and more intuitive for consumers to adopt.

- Policy Alignment and True Circularity—SPR complements evolving policy directions where producer obligations are increasingly split among actors in the supply chain, as seen in the UK’s Producer Responsibility Obligations [135] and schemes in Germany [129] and Sweden [136]. More importantly, it provides the governance architecture needed to achieve true circularity. By fostering collaboration from the design phase through to end-of-life, SPR helps to operationalise circular principles like designing out waste and keeping materials in use at their highest value, moving beyond the linear focus of traditional EPR schemes.

- Risk Mitigation and Systems Integration—Shared accountability also spreads reputational and compliance risks across stakeholders, reducing the vulnerability of any single entity to public or regulatory backlash. Moreover, it facilitates the integration of complex reverse logistics systems and closed-loop recycling, which are critical components of the circular economy transition. When responsibility is shared, infrastructure investments and behaviour change campaigns can be coordinated, scalable, and strategically targeted for maximum impact.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Contributions of the Study

- Theoretical Contribution: The primary theoretical contribution is the articulation and positioning of Shared Producer Responsibility (SPR) as a necessary evolution of the traditional EPR model. By empirically demonstrating the structural disconnect between the actors with technical control (packaging manufacturers) and those with legal responsibility (FMCG brands), this paper provides a clear rationale for a more distributed accountability framework. The study further contributes by proposing a conceptual framework that synthesises six key strategies into a unified, synergistic model. The novelty of this framework lies not in the individual strategies themselves, but in its emphasis on their integrated application, which illustrates a practical pathway for implementing SPR and achieving systemic change.

- Methodological Contribution: The study’s dual approach of combining a systematic literature review with an analysis of corporate ESG reports provides a unique contribution by bridging academic theory with real-world corporate practice. This integrated method allowed for a more nuanced analysis, revealing the gap between the challenges discussed in the literature and the on-the-ground reporting behaviours of leading firms.

- Practical Contribution: From a practical standpoint, the conceptual framework offers a clear roadmap for managers aiming to accelerate the transition to sustainable packaging. The analysis of ESG reporting inconsistencies provides tangible evidence of the need for standardised reporting practices, a key recommendation for industry associations. Finally, the SPR model provides a blueprint for companies to engage in more effective, collaborative partnerships across the value chain.

- Policy Contribution: This study offers a significant contribution to environmental policy by proposing the SPR model as a concrete and actionable alternative to traditional EPR frameworks. By highlighting the systemic flaws that arise from misaligned responsibility in the current system, this paper provides policymakers with a clear rationale for regulatory reform. The conceptual framework serves as a practical tool for designing integrated policy mixes that combine regulations, incentives, and consumer-facing initiatives to create a more coherent and effective governance system for sustainable packaging.

6.2. Limitations of the Study

6.3. Future Research Agenda

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Sr. No | Title of the Article | Research Type and Methodology | Industry Focus | Research Area | Key Findings and Themes Identified | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A consumer definition of eco-friendly packaging | Empirical—Qualitative | FMCG | Stakeholder | The article defines eco-friendly packaging based on consumer preferences, emphasising recyclability, biodegradability, minimalism, renewable resources, energy efficiency, and ethics. It highlights the gap between consumer expectations and industry practices, underscoring the need for more consumer-informed packaging strategies. | [6] |

| 2 | Characterisation and environmental value proposition of reuse models for fast-moving consumer goods: Reusable packaging and products | Empirical—Mixed Methods | FMCG | Packaging | The study characterises reuse models, identifying significant environmental benefits like material and energy savings. It also outlines current challenges like product design limitations. Contributions include a framework to categorise reuse models, aiding industry stakeholders in improving sustainable practices. | [7] |

| 3 | Exploring green packaging acceptance in fast moving consumer goods in emerging economy: The case of Malaysia | Empirical—Quantitative | FMCG | Stakeholder | Shows positive Malaysian consumer attitudes toward innovative and distinctive green packaging, highlighting the critical role of uniqueness and innovativeness. Identifies a key barrier: perceived cost implications. | [65] |

| 4 | Exploring relationship among semiotic product packaging, brand experience dimensions, brand trust and purchase intentions in an Asian emerging market | Empirical—Quantitative | FMCG | Stakeholder | Finds significant connections between semiotic packaging and brand experience dimensions, influencing trust and purchase intentions. Emphasises the crucial role of visual and symbolic packaging elements in shaping consumer behaviour in emerging markets. | [72] |

| 5 | Factors for eliminating plastic in packaging: The European FMCG experts’ view | Empirical—Qualitative | FMCG | Stakeholder | Identifies factors influencing European FMCG experts’ decisions to eliminate plastic packaging, highlighting consumer awareness, government policy, and technological innovations as enablers. Also recognises existing barriers like high costs and logistical complexities. | [9] |

| 6 | Influencing Factors for Consumers’ Intention to Reduce Plastic Packaging in Different Groups of Fast-Moving Consumer Goods in Germany | Empirical—Quantitative | FMCG | Stakeholder | Highlights how environmental attitudes and social and personal norms significantly influence consumer intentions to minimise plastic packaging, especially in food and textiles. Emphasises tailored interventions for specific product categories to enhance sustainable consumer behaviours. | [68] |

| 7 | Packaging-influenced-purchase decision segment the bottom of the pyramid consumer marketplace? Evidence from West Bengal, India | Empirical—Quantitative | FMCG | Stakeholder | Identifies significant differences in packaging-driven purchase behaviours among urban and rural bottom-of-pyramid (BoP) consumers in West Bengal, with urban consumers being most influenced by packaging attributes. Suggests customised strategies addressing diverse segment needs. | [66] |

| 8 | Purchase Behavior of Young Consumers Toward Green Packaged Products in Vietnam | Empirical—Qualitative | FMCG | Stakeholder | Reveals that attitudes, environmental concerns, knowledge, and trust strongly influence young Vietnamese consumers’ decisions to buy green-packaged products. Suggests strategies emphasising awareness and trust-building to foster sustainable consumption patterns. | [64] |

| 9 | Recycling of multi-material multilayer plastic packaging: Current trends and future scenarios | Empirical—Qualitative | FMCG | Packaging | Addresses recycling complexities for multi-material multilayer plastics, outlining current trends and challenges due to difficult-to-recycle materials. Suggests innovations in recycling technologies and design improvements to enhance recycling efficiency. | [46] |

| 10 | Reusability and recyclability of plastic cosmetic packaging: A life cycle assessment | Empirical—Qualitative | FMCG | Packaging | Presents lifecycle assessments emphasising the critical role of reusability and recyclability in plastic cosmetic packaging sustainability. Highlights design improvements as essential for reducing environmental impact and promoting sustainable product practices. | [2] |

| 11 | Sustainable packaging in the FMCG industry | Empirical—Qualitative | FMCG | Stakeholder | Explores consumer perceptions and behaviour toward sustainable packaging in FMCG. Highlights the importance of material selection, technology, and market appeal, identifying consumer education as critical for fostering broader acceptance and use. | [8] |

| 12 | Sustainable Packaging Practices Across Various Sectors: Some Innovative Initiatives Under the Spotlight | Empirical—Qualitative | FMCG | Packaging | Discusses innovative sustainable packaging initiatives across multiple industries, emphasising best practices and key challenges. Highlights technology, material innovation, and consumer engagement as essential for achieving sustainability. | [70] |

| 13 | Corporate self-commitments to mitigate the global plastic crisis: Recycling rather than reduction and reuse | Theoretical—Qualitative | FMCG | Packaging | Highlights corporate preference for recycling over reduction and reuse strategies. Companies misalign “reduction” practices with waste hierarchy standards, suggesting a need for realignment with effective sustainability principles. | [14] |

| 14 | Impact of Packaging Fast-Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) on Consumer Buying Behaviour- A Review of Literature | Review—Qualitative | FMCG | Stakeholder | Reviews packaging’s significant influence on consumer purchasing behaviour in FMCG, stressing elements like colour, design, and sustainability attributes. Advocates packaging improvements to enhance consumer appeal and product differentiation. | [1] |

| 15 | Circular business models for the fastmoving consumer goods industry: Desirability, feasibility, and viability | Empirical—Mixed Methods | FMCG | Stakeholder | Identifies key success factors for reusable packaging models in FMCG, emphasising partnerships, consumer involvement, profitability, operational efficiency, and supply chain innovation. Promotes strategic collaborations for circular business model effectiveness. | [74] |

| 16 | Investigation into circular economy of plastics: The case of the UK fast moving consumer goods industry | Case Study—Qualitative | FMCG | Packaging | Highlights barriers (technical challenges, aesthetics) and enablers (regulatory support, consumer awareness) of plastics circular economy in UK FMCG. Suggests targeted interventions to overcome implementation challenges effectively. | [75] |

| 17 | Role of green and multisensory packaging in environmental sustainability: Evidence from FMCG sector of Pakistan | Empirical—Quantitative | FMCG | Packaging | Finds green packaging positively influences environmental sustainability, while multisensory packaging negatively impacts it. Consumer perceptions significantly moderate multisensory packaging effects, underscoring perception management for sustainable outcomes. | [71] |

| 18 | An Explorative Study on Packaging-Saving Consumer Practices in the Fast-Moving Consumer Goods Sector | Empirical—Quantitative | FMCG | Stakeholder | Examines how customers practise packaging-saving techniques like reducing and reusing packaging. Cost savings and environmental concerns are among the motivators, but convenience and product design are also obstacles. It draws attention to how crucial consumer behaviour is in promoting environmentally friendly packaging initiatives. | [115] |

| 19 | Simplicity Matters: Unraveling the Impact of Minimalist Packaging on Green Trust in Daily Consumer Goods | Empirical—Quantitative | FMCG | Stakeholder | Investigates the impact of minimalist packaging on consumers’ views of environmental responsibility, particularly “green trust”, in everyday consumer goods. By communicating simplicity, authenticity, and reduced environmental impact, minimalist design can increase green trust. For brands looking to establish long-term credibility, minimalist packaging can be an effective tool. | [73] |

| 20 | A review on consumer sorting behaviour: Spotlight on food and Fast Moving Consumer Goods plastic packaging | Review—Qualitative | FMCG | Stakeholder | The study classifies the sorting factors into four groups: packaging design, internal consumer traits, sociodemographic variables, and external conditions. There is a need for clearer labelling and better consumer education for proper sorting. The authors suggest standardising labels, improved design, and investigating behavioural techniques and policy tools, for sorting properly plastic packaging. | [69] |

| 21 | Factors associated with Finnish, German and UK consumers’ intentions to test, buy and recommend reusable fast-moving consumer goods packaging | Empirical—Quantitative | FMCG | Stakeholder | The research concludes that consumers’ intentions are more strongly influenced by positive emotions, such as pride and joy, than by more conventional cognitive factors, such as attitude. It indicates that emotional engagement may be more important in promoting reusable packaging than rational evaluations. | [114] |

| 22 | The Role of Sustainable Packaging in Saudi Arabian Supply Chains FMCG: Analyzing Consumer Acceptance and Marketing Strategies for Enhancing Environmental Impact | Empirical—Quantitative | FMCG | Stakeholder | The study suggests that environmental values are more important to consumers than price. Satisfaction and demand are increased by environmental consciousness. Positive visualisations enhance consumer advocacy and perceptions—but purchasing behaviour is not necessarily affected. | [67] |

Appendix A.2

| Sr. No | Title of the Article | Research Type and Methodology | Industry Focus | Research Area | Key Findings and Themes Identified | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Consumer Perceptions of Food Packaging in Its Role in Fighting Food Waste | Empirical—Mixed Methods | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Explores consumer perceptions of packaging effectiveness against food waste, revealing positive insights into sustainable behaviour. Limitations include its single-country focus, suggesting broader geographic studies. Contributions emphasise practical strategies for reducing food waste through better packaging designs. | [103] |

| 2 | Consumers’ response to environmentally friendly food packaging—A systematic review | Systematic Review—Qualitative | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Identifies factors affecting consumer responses to sustainable packaging and highlights gaps in current research. Limitations include reliance on convenience samples and minimal probabilistic studies. It suggests deeper investigations into consumer attitudes for designing impactful sustainable packaging. | [88] |

| 3 | Consumers’ awareness of plastic packaging: More than just environmental concerns | Empirical—Quantitative | Packaging | Stakeholder | Investigates consumer awareness and attitudes toward plastic packaging, finding multidimensional environmental and practical concerns. Limitations include limited demographic coverage. Contributions enrich understanding of how awareness influences consumer behaviour, supporting targeted interventions. | [89] |

| 4 | Double-edged sword effect of packaging: Antecedents and consumer consequences of a company’s green packaging design | Empirical—Mixed Methods | Packaging | Stakeholder | Demonstrates that employee psychological ownership enhances green packaging designs, significantly influencing consumers’ green purchasing behaviour. It underscores the dual impact of green packaging as both beneficial and challenging, influencing consumer trust and perceptions. | [81] |

| 5 | Eco-friendly alternatives to food packed in plastics: German consumers’ purchase intentions for different bio-based packaging strategies | Empirical—Mixed Methods | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Finds German consumers favour paper-based bio-packaging due to perceived eco-friendliness, significantly impacting purchase intentions. Highlights varying consumer preferences across packaging types, emphasising consumer perceptions as critical in packaging strategy. | [82] |

| 6 | Effect of executional greenwashing on market share of food products: An empirical study on green-coloured packaging | Empirical—Mixed Methods | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Indicates that green-coloured packaging significantly increases market share, supporting concerns about greenwashing. Highlights ethical implications and consumer trust issues, urging clearer standards to protect consumers and ensure transparency. | [83] |

| 7 | Environmental sustainability of liquid food packaging: Is there a gap between Danish consumers’ perception and learnings from life cycle assessment? | Empirical—Mixed Methods | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Explores discrepancies between Danish consumer perceptions and actual lifecycle assessments regarding liquid food packaging sustainability. Highlights misalignment and urges improved consumer education to bridge the knowledge gap. | [102] |

| 8 | Incorporating consumer insights into the UK food packaging supply chain in the transition to a circular economy | Empirical—Qualitative | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Highlights the importance of consumer behaviour insights in promoting circular economy practices within the UK food packaging sector. It emphasises improved communication and smart technologies to facilitate sustainable disposal practices. | [78] |

| 9 | Plastic or not plastic? That’s the problem: analysing the Italian students purchasing behavior of mineral water bottles made with eco-friendly packaging | Empirical—Qualitative | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Investigates Italian students’ preferences for eco-friendly bottled water packaging, highlighting critical purchasing behaviours and eco-awareness. Suggests increased consumer education about sustainability to drive effective transition toward environmentally friendly packaging alternatives. | [87] |

| 10 | Signs of Use Present a Barrier to Reusable Packaging Systems for Takeaway Food | Empirical—Qualitative | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Highlights consumer resistance to reusable packaging in takeaway foods due to visible signs of prior use, impacting adoption rates negatively. Suggests the importance of perception management, cleanliness assurances, and packaging designs to overcome acceptance barriers. | [94] |

| 11 | Single-use plastic packaging in the Canadian food industry: consumer behavior and perceptions | Empirical—Qualitative | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Explores Canadian consumer attitudes toward single-use plastics, emphasising environmental concerns. Suggests opportunities for consumer education and alternative packaging innovations, reflecting increasing consumer willingness to adopt sustainable packaging options. | [90] |

| 12 | Stakeholder engagement toward value co-creation in the F&B packaging industry | Empirical—Qualitative | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Emphasises stakeholder collaboration in driving sustainability within the food and beverage packaging sector, highlighting effective co-creation models involving businesses, consumers, and policymakers. Advocates increased engagement for impactful, collective sustainability initiatives. | [27] |

| 13 | Sustainability governance and contested plastic food packaging e An integrative review | Review—Qualitative | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Examines complexities in sustainability governance for plastic packaging, emphasising roles of policymakers, businesses, and consumers. Highlights stakeholder conflicts and cooperation, suggesting integrated governance strategies for advancing sustainability goals. | [77] |

| 14 | The Effect of Sustainable Packaging Aesthetic Over Consumer Behavior: A Case Study from India | Case Study—Quantitative | Packaging | Stakeholder | Highlights sustainable packaging aesthetics significantly influencing Indian consumers’ behaviours and preferences. Illustrates that visually appealing sustainable packaging notably impacts consumer choices, suggesting aesthetics as a key component in packaging strategies. | [84] |

| 15 | The persuasive effects of emotional green packaging claims | Empirical—Qualitative | Packaging | Stakeholder | Finds emotional green packaging claims highly influential on consumer purchase decisions compared to rational or neutral messages. Suggests leveraging emotional appeals to effectively encourage sustainable consumer behaviours. | [80] |

| 16 | What affect consumers’ willingness to pay for green packaging? Evidence from China | Empirical—Quantitative | Supply Chain | Stakeholder | Reveals factors influencing Chinese consumers’ willingness to pay for green packaging, including package price, convenience, reusability, and protective capability. Advocates enhanced consumer education and economic incentives for adoption. | [98] |

| 17 | What do consumers care about when purchasing experiential packaging? | Empirical—Quantitative | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Highlights consumer preferences for engagement, branding, and economic considerations in experiential packaging. Emphasises effective design strategies as crucial for successful commercialisation and increased consumer acceptance. | [95] |

| 18 | Consumer Considerations for the Implementation of Sustainable Packaging: A Review | Review—Mixed Methods | Packaging | Stakeholder | Outlines critical consumer considerations for adopting sustainable packaging, emphasising tangible sustainability information and effective leadership. Highlights the importance of clear consumer communication and educational initiatives. | [5] |

| 19 | Managing the transition to eco-friendly packaging—An investigation of consumers’ motives in online retail | Empirical—Quantitative | E-commerce | Stakeholder | Finds consumers’ eco-friendly packaging choices in online clothing retail driven by gain and normative motives, informed by goal-framing theory. Suggests emphasising reliability and consumer willingness to pay for increased adoption. | [92] |

| 20 | Packaging-free practices in food retail: the impact on customer loyalty | Empirical—Qualitative | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Indicates packaging-free retail positively affects brand image, satisfaction, and customer loyalty. However, the expected effects of brand trust on loyalty were not confirmed, suggesting nuanced relationship management strategies. | [93] |

| 21 | Paper Meets Plastic: The Perceived Environmental Friendliness of Product Packaging | Empirical—Mixed Methods | Packaging | Stakeholder | Reveals consumer bias favouring plastic packaging enhanced with paper, due to simplistic environmental perceptions. Suggests educational efforts to correct consumer misconceptions and drive truly sustainable choices. | [86] |

| 22 | Recycled or reusable: A multi-method assessment of eco-friendly packaging in online retail | Empirical—Mixed Methods | E-commerce | Stakeholder | Identifies mismatches among retailers’ assumptions, consumer preferences, and actual environmental impacts regarding packaging in online retail. Highlights need for improved retailer awareness and better alignment with consumer expectations. | [76] |

| 23 | Achieving sustainable development with sustainable packaging: A natural-resource-based view perspective | Review Qualitative | Packaging | Stakeholder | Identifies three resource-based competencies—sustainable development, product stewardship, and pollution prevention—as essential facilitators for businesses implementing sustainable packaging to improve environmental performance and gain a competitive edge. Highlights how sustainability can be strategically incorporated into essential business processes. | [101] |

| 24 | Creating conditions for sustainability transformation through transformative governance—The case of plastic food packaging in Finland | Case study Qualitative | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Finland’s plastic food packaging governance is primarily reactive despite having many transformative components, such as cooperation and policy integration. Recycling is prioritised over cutting back on single-use packaging. Innovation is scarce, and voluntary initiatives are insufficient to bring about significant change. More proactive policies, stronger regulation, and clearer direction are needed. | [97] |

| 25 | Introducing reusable food packaging: Customer preferences and design implications for successful market entry | Empirical—Quantitative | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Investigates consumer preferences for reusable food packaging and how these can influence effective marketing and design tactics. It concludes that the main elements influencing consumer acceptance are convenience, hygiene, ease of return, and unambiguous information. Alignment with sustainability principles and provider trust are also crucial. | [96] |

| 26 | One Year of Mandatory Reusable Packaging in Germany: Opportunities and Obstacles from the Perspective of Consumers and Companies | Empirical—Quantitative | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Examines Germany’s first year of requiring takeaway food and drink to be packaged in reusable containers. Despite a rise in awareness, adoption is still constrained by behavioural, financial, and logistical issues. Customers prioritise convenience over sustainability. To put in place efficient reuse systems, businesses require more precise instructions and support. | [100] |

| 27 | Switching to Reuse: The Impact of Information on Consumers’ Choices for Reusable Food Packaging | Empirical—Quantitative | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Reveals that when consumers are aware of the environmental advantages of reusable options, particularly with regard to CO2 reduction, they are more inclined to select them. The effectiveness of environmental messaging, changes in consumer behaviour, and the significance of clear communication in promoting sustainable choices are some of the major themes. | [79] |

| 28 | The Impact of Food Packaging Design on Users’ Perception of Green Awareness | Empirical—Mixed Methods | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Investigates how packaging’s informational and visual components affect consumers’ opinions about how environmentally friendly a product is. Design elements like colour, imagery, and eco-labels have a big impact on how consumers perceive and assess products. It highlights consumer trust, the importance of aesthetics in sustainability messaging, and how packaging design fits in with environmentally conscious branding. | [85] |

| 29 | How consumers value sustainable packaging: an experimental test combining packaging material, claim and price | Empirical—Quantitative | Food and Beverage | Stakeholder | Examines how young adults view and select food items based on packaging indicators such as price, recycled content claims, and material (glass vs. plastic). According to the study, claims about glass and recycled materials both improve perceptions of sustainability and product quality because of the “halo effect,” but when a price premium is applied, consumers are much less likely to choose these options. | [99] |

| 30 | Purchasing Intention of Products with Sustainable Packaging | Empirical—Quantitative | Packaging | Stakeholder | Purchase intention is greatly increased by perceived value, environmental concern, and eco-label credibility. Personal norms and social influence are also significant factors, particularly for consumers who care about the environment. According to the findings, promoting green purchasing behaviour requires clear communication and credible sustainability claims. | [91] |

Appendix A.3

| Sr. No | Title of the Article | Research Type and Methodology | Industry Focus | Research Area | Key Findings and Themes Identified | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Environmentally sustainable plastic food packaging: A holistic life cycle thinking approach for design decisions | Empirical—Quantitative | Food and Beverage | Packaging | Advocates a comprehensive lifecycle approach for sustainable plastic packaging design, considering environmental impacts throughout the lifecycle. Limitations include insufficient attention to alternative materials. The approach emphasises holistic sustainability strategies. | [104] |

| 2 | Packaging, business, and society | Empirical—Quantitative | Packaging | Packaging | Examines the complex relationship between packaging, businesses, and societal expectations, emphasising increased demand for sustainable solutions. Highlights diverse stakeholder roles, including businesses, consumers, and regulatory entities driving packaging innovation. | [113] |

| 3 | Sustainable packaging for supply chain management in the circular economy: A review | Systematic Review—Qualitative | Supply Chain | Packaging | Reviews sustainable packaging practices in supply chain management, highlighting circular economy opportunities and challenges. Emphasises the adoption of recyclable materials, waste reduction, and effective logistics as critical strategies for sustainable growth. | [106] |

| 4 | The commitment of packaging industry in the framework of the european strategy for plastics in a circular economy | Empirical—Qualitative | Packaging | Packaging | Highlights the European packaging industry’s significant efforts toward circular plastics strategies, emphasising challenges like recyclability and material selection. Advocates stronger collaboration and policy support to achieve European sustainability objectives. | [108] |

| 5 | Understanding plastic packaging: The co-evolution of materials and society | Theoretical and Case Study—Qualitative | Packaging | Packaging | Discusses the dynamic relationship between packaging innovations, consumer behaviour, and societal norms. Highlights complexity in achieving sustainability, emphasising the necessity of integrated technological and societal changes. | [112] |

| 6 | Sustainability in e-commerce packaging: A review | Systematic Review—Qualitative | E-commerce | Packaging | Highlights strategies to reduce environmental impacts in e-commerce packaging, including circular packaging systems, reducing overpackaging, and adopting technologies like 3D printing. Recognises limitations due to reliance on the existing literature rather than primary research. | [10] |

| 7 | Plastic pollution and packaging: Corporate commitments and actions from the food and beverage sector | Empirical— Qualitative | Food and Beverage | Packaging | Reveals that many companies avoid directly addressing plastic pollution in reports, preferring neutral language. Few companies detail actionable commitments. Suggests transparency improvements for clearer corporate accountability and action. | [109] |

| 8 | Achieving the circular economy through environmental policies: Packaging strategies for more sustainable business models in the wine industry | Empirical—Mixed Methods | Food and Beverage | Packaging | Demonstrates environmental and economic benefits from sustainable packaging strategies using lifecycle assessment in the Italian wine industry. Highlights significant reductions in emissions and costs, suggesting broader industry applicability. | [105] |

| 9 | Investigating sustainability tensions and resolution strategies in the plastic food packaging industry—A paradox theory approach | Empirical–Qualitative | Food and Beverage | Packaging | Identifies significant sustainability tensions in plastic packaging (operations, recycling, stakeholder relations). Suggests resolution via collaborative, innovative, and circular approaches, promoting multi-stakeholder engagements for sustainability. | [110] |

| 10 | Enhancing circular supply chains via ecological packaging: An empirical investigation of an extended producer responsibility network | Empirical—Quantitative | Supply Chain | Packaging | The literature identifies several key drivers for adopting sustainable packaging, such as stringent environmental laws, internal cooperation, and consumer demand. In a counter-intuitive finding, the same study provides evidence that firms with more limited financial resources are also more likely to adopt ecological packaging, as they are motivated by the potential for cost and resource efficiencies. The study further notes that the positive effect of customer demand is weakened in highly competitive markets. | [111] |

| 11 | Environmental analysis of returnable packaging systems in different eCommerce business and packaging management models | Empirical—Case study | E-commerce | Packaging | When return logistics are effective and reuse rates are high, returnable systems can drastically cut down on emissions and resource consumption. Variables like return rates, cleaning procedures, and transportation distance have a significant impact on environmental benefits. Maximising sustainability results requires optimising user compliance and logistics. | [107] |

References

- Bulama, M.; Halliru, M.; Maiyaki, A.A. Impact of Packaging Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) on Consumer Buying Behaviour—A Review of Literature. Afr. Sch. J. Mgt. Sci. Entrep. 2021, 22, 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gatt, I.J.; Refalo, P. Reusability and recyclability of plastic cosmetic packaging: A life cycle assessment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2022, 15, 200098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Packaging Waste Statistics-Statistics Explained. 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Packaging_waste_statistics (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs. UK Statistics on Waste. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-waste-data/uk-statistics-on-waste#packaging-waste (accessed on 31 August 2023).

- Boz, Z.; Korhonen, V.; Sand, C.K. Consumer Considerations for the Implementation of Sustainable packaging: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Parker, L.; Brennan, L.; Lockrey, S. A consumer definition of eco-friendly packaging. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muranko, Ż.; Tassell, C.; Zeeuw van der Laan, A.; Aurisicchio, M. Characterisation and Environmental Value Proposition of Reuse Models for Fast Moving Consumer Goods: Reusable Packaging and Products. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Hudnurkar, M. Sustainable Packaging in the FMCG Industry. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2022, 7, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Park, C.; Moultrie, J. Factors for eliminating plastic in packaging: The European FMCG experts’ view. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escursell, S.; Massana, P.L.; Roncero, M.B. Sustainability in e-commerce packaging: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verghese, K.; Lewis, H.; Fitzpatrick, L. Packaging for Sustainability; Springer: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pålsson, H.; Hellström, D. Packaging logistics in supply chain practice–current state, trade-offs and improvement potential. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2016, 19, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loop. Purpose. 2023. Available online: https://exploreloop.com/purpose/ (accessed on 31 August 2023).

- Rhein, S.; Sträter, K.F. Corporate self-commitments to mitigate the global plastic crisis: Recycling rather than reduction and reuse. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, M. Stage model research in the UK fast moving consumer goods industry. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2006, 9, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Sustainable Development. Goal 12: Ensure Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns. 2023. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production/ (accessed on 31 August 2023).

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 13: Take Urgent Action to Combat Climate Change and Its Impacts. 2023. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/climate-change/ (accessed on 31 August 2023).

- Ed-Dafali, S.; Adardour, Z.; Derj, A.; Bami, A.; Hussainey, K. A PRISMA-Based Systematic Review on Economic, Social, and Governance Practices: Insights and Research Agenda. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 1896–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosi, M.K.; Lajuni, N.; Wellfren, A.C.; Lim, T.S. Sustainability Reporting through Environmental, Social, and Governance: A Bibliometric Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halid, S.; Rahman, R.A.; Mahmud, R.; Mansor, N.; Wahab, R.A. A Literature Review on ESG Score and Its Impact on Firm Performance. Int. J. Acad. Res. Account. Financ. Manag. Sci. 2023, 13, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Official Journal of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2022/2464 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 amending Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Directive 2013/34/EU, as Regards Corporate Sustainability Reporting (Text with EEA Relevance). 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2022/2464/oj (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Puzniak-Holford, M.; Subramoni, A.; Brennan, S. EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)-Strategic and Operational Implications|Deloitte UK. 2023. Available online: https://www.deloitte.com/uk/en/Industries/financial-services/blogs/eu-corporate-sustainability-reporting-directive-csrd-strategic-and-operational-implications.html (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- European Commission. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council Amending Directive 2013/34/EU, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, as Regards Corporate Sustainability Reporting. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0189 (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, S.; Nuzum, A.-K.; Schaltegger, S. Stakeholder expectations on sustainability performance measurement and assessment. A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 217, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomarra, M.; Crescimanno, M.; Sakka, G.; Galati, A. Stakeholder engagement toward value co-creation in the F&B packaging industry. EuroMed J. Bus. 2020, 15, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, N.; Akbar, S.; Situ, H.; Ji, S.; Parikh, N. Sustainable development goal reporting: Contrasting effects of institutional and organisational factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 411, 137339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide), 7th ed; Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Found, P.; Rich, N. The meaning of lean: Cross case perceptions of packaging businesses in the UK’s fast moving consumer goods sector. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2007, 10, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on Conducting a Systematic Literature Review. J. Plann. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastre, R.M.; De Paula, I.C.; Echeveste, M.E.S. A Systematic Literature Review on Packaging Sustainability: Contents, Opportunities, and Guidelines. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugaard, D.; Ding, A. Global Drivers for ESG Performance: The Body of Knowledge. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlinson, M.; Harvey, C.; Kelly, A.; Morris, H. The use and abuse of journal quality lists. Organization 2011, 18, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfanti, A.; De Crescenzo, V.; Simeoni, F.; Adaui, C.R.L. Convergences and divergences in sustainable entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship research: A systematic review and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 170, 114336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264. Available online: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 (accessed on 1 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sari, M.P.; Dewi, S.R.K.; Raharja, S.; Dinanti, A.; Rizkyana, F.W. Good corporate governance as moderation on sustainability report disclosure. J. Gov. Regul. 2023, 12, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qorri, A.; Mujkić, Z.; Kraslawski, A. A conceptual framework for measuring sustainability performance of supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 189, 570–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stora Enso. Storo Enso Annual Report 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.storaenso.com/-/media/documents/download-center/documents/annual-reports/2022/storaenso_annual_report_2022.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- DS Smith. DS Smith Sustainability Report 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.dssmith.com/sustainability/reporting-hub/sustainabilityreport (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Smurfit Kappa. Smurfit Kappa Sustainable Development Report 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.smurfitkappa.com/sustainability/download-centre?documentdocumenttypes=&documentdocumentdateyear=2022 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Tetra Pak. Tetra Pak Sustainability Report FY22. 2023. Available online: https://www.tetrapak.com/content/dam/tetrapak/media-box/global/en/documents/sustainability-report-FY22-download.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Amcor. Amcor Sustainability Report 2022. 2023. Available online: https://assets.ctfassets.net/f7tuyt85vtoa/3xUMcwnCv4yUBsIlOLz3EE/655a028a95896ff00c764547da185a17/1_Amcor_Sustainability_Report_2022_Full_Report_WEB_SP.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Mondi Group. Mondi Group UN Sustainable Development Goals Index 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.mondigroup.com/globalassets/mondigroup.com/sustainability/reports-and-publications/2022/mondi-sdg-index-2022.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Mondi Group. Mondi Group Sustainable Development Report 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.mondigroup.com/globalassets/mondigroup.com/sustainability/reports-and-publications/2022/mondi-sustainable-development-report-2022-v2.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Nestle. Creating Shared Value and Sustainability Report 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.nestle.com/sites/default/files/2023-03/creating-shared-value-sustainability-report-2022-en.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Unilever. Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.unilever.com/investors/annual-report-and-accounts/archive-of-annual-report-and-accounts/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Danone. Integrated Annual Report 2022-Danone’s Sustainability Performance. 2023. Available online: https://www.danone.com/content/dam/corp/global/danonecom/rai/2022/danone-integrated-annual-report-2022.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Reckitt. Sustainability Insights 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.reckitt.com/media/mojal0zt/sustainability-insights-2022.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Coca-Cola Company. The Coca-Cola Company 2022 Business & Sustainability Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.coca-colacompany.com/content/dam/company/us/en/reports/coca-cola-business-sustainability-report-2022.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Coca-Cola Company. The Coca-Cola Company 2022 Reporting Frameworks & SDGs. 2023. Available online: https://www.coca-colacompany.com/content/dam/company/us/en/reports/2022-business-report/2022-reporting-framework-indexes.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Stora Enso. About Stora Enso. 2023. Available online: https://www.storaenso.com/en/about-stora-enso (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- DS Smith. Who We Are-DS Smith. 2023. Available online: https://www.dssmith.com/uk/about/who-we-are (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Smurfit Kappa. At a Glance. 2023. Available online: https://www.smurfitkappa.com/about/at-a-glance (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Tetra Pak. About Tetra Pak. 2023. Available online: https://www.tetrapak.com/en-gb/about-tetra-pak (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Amcor. About Amcor. 2023. Available online: https://www.amcor.com/about (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Mondi Group. About Mondi. 2023. Available online: https://www.mondigroup.com/en/about-mondi/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Nestle. About Us. 2023. Available online: https://www.nestle.com/about (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Unilever. We Are Unilever. 2023. Available online: https://www.unilever.co.uk/our-company/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Danone. At a Glance. 2023. Available online: https://www.danone.com/about-danone/at-a-glance.html (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Reckitt. Our Company. 2023. Available online: https://www.reckitt.com/our-company/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Coca-Cola Company. Our Company. 2023. Available online: https://www.coca-colacompany.com/about-us (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Nguyen, N.T.; Nguyen, L.H.A.; Tran, T.T. Purchase Behavior of Young Consumers Toward Green Packaged Products in Vietnam. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, S.; Osman, L.; Koay, S.; Long, K. Exploring Green Packaging Acceptance in Fast Moving Consumer Goods in Emerging Economy: The Case of Malaysia. LogForum 2021, 17, 503–517. [Google Scholar]

- Panda, D.; Masani, S.; Dasgupta, T. Packaging-influenced-purchase decision segment the bottom of the pyramid consumer marketplace? Evidence from West Bengal, India. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2022, 27, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahareth, A.; Soliman, K. The Role of Sustainable Packaging in Saudi Arabian Supply Chains FMCG: Analyzing Consumer Acceptance and Marketing Strategies for Enhancing Environmental Impact. J. Ecohuman 2025, 3, 11969–11988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.A.; Profeta, A.; Decker, T.; Smetana, S.; Menrad, K. Influencing Factors for Consumers’ Intention to Reduce Plastic Packaging in Different Groups of Fast Moving Consumer Goods in Germany. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielinger, E.; Weinrich, R. A review on consumer sorting behaviour: Spotlight on Food and Fast Moving Consumer Goods Plastic Packaging. Environ. Dev. 2023, 47, 100890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R. Sustainable Packaging Practices Across Various Sectors: Some Innovative Initiatives Under the Spotlight. Oper. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 15, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, R.M.; Sabir, I.; Martins, J.M.; Majid, M.B.; Rafiq, M.; Martins, J.N.; Rana, K. Role of green and multisensory packaging in environmental sustainability: Evidence from FMCG sector of Pakistan. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2285263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, M.; Misra, R.; Singh, D. Exploring relationship among semiotic product packaging, brand experience dimensions, brand trust and purchase intentions in an Asian emerging market. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022, 35, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Meng, X.; Sun, C. Simplicity Matters: Unraveling the Impact of Minimalist Packaging on Green Trust in Daily Consumer Goods. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Harsch, A.; Weissbrod, I. Circular business models for the fastmoving consumer goods industry: Desirability, feasibility, and viability. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Putnam, E.; You, W.; Zhao, C. Investigation into circular economy of plastics: The case of the UK fast moving consumer goods industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frommeyer, B.; Koch, J.; Scagnetti, C.; Lorenz, M.; Schewe, G. Recycled or reusable: A multi-method assessment of eco-friendly packaging in online retail. J. Ind. Ecol. 2023, 28, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundqvist-Andberg, H.; Åkerman, M. Sustainability governance and contested plastic food packaging–An integrative review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 306, 127111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.; Trimingham, R.; Wilson, G.T. Incorporating Consumer Insights into the UK Food Packaging Supply Chain in the Transition to a Circular Economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastria, S.; Vezzil, A.; De Cesarei, A. Switching to Reuse: The Impact of Information on Consumers’ Choices for Reusable Food Packaging. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aagerup, U.; Frank, A.-S.; Hultqvist, E. The persuasive effects of emotional green packaging claims. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 3233–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-W. Double-edged sword effect of packaging: Antecedents and consumer consequences of a company’s green packaging design. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 406, 137037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macht, J.; Klink-Lehmann, J.; Venghaus, S. Eco-friendly alternatives to food packed in plastics: German consumers’ purchase intentions for different bio-based packaging strategies. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 109, 104884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boncinelli, F.; Gerini, F.; Piracci, G.; Bellia, R.; Casini, L. Effect of executional greenwashing on market share of food products: An empirical study on green-coloured packaging. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 391, 136258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapse, U.; Mahajan, Y.; Hudnurkar, M.; Ambekar, S.; Hiremath, R. The Effect of Sustainable Packaging Aesthetic on Consumer Behavior: A Case Study from India. Australas. Account. Bus. Financ. J. 2023, 17, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, H. The Impact of Food Packaging Design on Users’ Perception of Green Awareness. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, T.; Krishna, A.; Döring, T. Paper Meets Plastic: The Perceived Environmental Friendliness of Product Packaging. J. Consum. Res. 2023, 50, 468–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, A.; Alaimo, L.S.; Ciaccio, T.; Vrontis, D.; Fiore, M. Plastic or not plastic? That’s the problem: Analysing the Italian students purchasing behavior of mineral water bottles made with eco-friendly packaging. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 179, 106060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketelsen, M.; Janssen, M.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ response to environmentally-friendly food packaging—A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhein, S.; Schmid, M. Consumers’ awareness of plastic packaging: More than just environmental concerns. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 162, 105063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.R.; McGuinty, E.; Charlebois, S.; Music, J. Single-use plastic packaging in the Canadian food industry: Consumer behavior and perceptions. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkowicz, A.C.; Pelegrini, T.; Bodah, B.W.; Rotini, C.D.; Moro, L.D.; Neckel, A.; Spanhol, C.P.; Araújo, E.G.; Pauli, J.; de Vargas Mores, G. Purchasing Intention of Products with Sustainable Packaging. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, J.; Frommeyer, B.; Schewe, G. Managing the transition to eco-friendly packaging–An investigation of consumers’ motives in online retail. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 351, 131504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, B.; Shojaei, A.S.; Miranda, H. Packaging-free practices in food retail: The impact on customer loyalty. Balt. J. Manag. 2023, 18, 474–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collis, B.; Baxter, W.; Baird, H.M.; Meade, K.; Webb, T.L. Signs of Use Present a Barrier to Reusable Packaging Systems for Takeaway Food. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-González, P.; Dopico-Parada, A.; López-Miguens, M.J. What do consumers care about when purchasing experiential packaging? Br. Food J. 2023, 126, 1887–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noëth, E.; Van Opstal, W.; Du Bois, E. Introducing reusable food packaging: Customer preferences and design implications for successful market entry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 6507–6532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundqvist, H.; Åkerman, M. Creating conditions for sustainability transformation through transformative governance–The case of plastic food packaging in Finland. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, H.; Sha, Y.; Ji, H.; Fan, J. What affect consumers’ willingness to pay for green packaging? Evidence from China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallez, L.; Spruyt, B.; Boen, F.; Smits, T. How consumers value sustainable packaging: An experimental test combining packaging material, claim and price. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 3566–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theobald, K.; Mich, A.; Hillesheim, S.; Hartard, S.; Rohn, H. One Year of Mandatory Reusable Packaging in Germany: Opportunities and Obstacles from the Perspective of Consumers and Companies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.C.I.; Wong, C.W.Y. Achieving sustainable development with sustainable packaging: A natural-resource-based view perspective. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2024, 33, 4766–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesen, S.; Bey, N.; Niero, M. Environmental sustainability of liquid food packaging: Is there a gap between Danish consumers’ perception and learnings from life cycle assessment? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 1193–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, L.; Francis, C.; Jenkins, E.L.; Schivinski, B.; Jackson, M.; Florence, E.; Parker, L.; Langley, S.; Lockrey, S.; Verghese, K.; et al. Consumer Perceptions of Food Packaging in Its Role in Fighting Food Waste. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagoda, S.U.M.; Gamage, J.R.; Karunathilake, H.P. Environmentally sustainable plastic food packaging: A holistic life cycle thinking approach for design decisions. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 400, 136680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, R.; Vicentini, F.; Botti, L.M.; Chiriacò, M.V. Achieving the circular economy through environmental policies: Packaging strategies for more sustainable business models in the wine industry. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2023, 33, 1497–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meherishi, L.; Narayana, S.A.; Ranjani, K.S. Sustainable Packaging for Supply Chain Management in the Circular economy: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Waqar, Z.; Snyder, W.R. Environmental analysis of returnable packaging systems in different eCommerce business and packaging management models. J. Ind. Ecol. 2024, 28, 1493–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foschi, E.; Bonoli, A. The Commitment of Packaging Industry in the Framework of the European Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, A.; Meissner, K.; Humphrey, J.; Ross, H. Plastic pollution and packaging: Corporate commitments and actions from the food and beverage sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 331, 129827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, A.; Sajjad, A. Investigating sustainability tensions and resolution strategies in the plastic food packaging industry—A paradox theory approach. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2023, 33, 2868–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flygansvær, B.; Dahlstrom, R. Enhancing circular supply chains via ecological packaging: An empirical investigation of an extended producer responsibility network. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 468, 142948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.M.; Parsons, R.; Jackson, P.; Greenwood, S.; Ryan, A. Understanding plastic packaging: The co-evolution of materials and society. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 65, 102166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtu, A.; Arendt, J.D. Packaging, business, and society. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2020, 25, e1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balatsas-Lekkas, A.; Luomala, H.; Pennanen, K. Factors associated with Finnish, German and UK consumers’ intentions to test, buy and recommend reusable fast-moving consumer goods packaging. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 52, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermehl, T.; Decker, T.; Menrad, K. An Explorative Study on Packaging-Saving Consumer Practices in the Fast-Moving Consumer Goods Sector. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kędzia, G.; Turek, J. What Hinders the Development of a Sustainable Compostable Packaging Market? Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 11, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The One Earth. Governance for sustainability. One Earth 2022, 5, 575–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemieniuch, C.E.; Waddell, F.N.; Sinclair, M.A. The role of ‘partnership’ in supply chain management for fast-moving consumer goods: A case study. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 1999, 2, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikström, F.; Williams, H.; Venkatesh, G. The influence of packaging attributes on recycling and food waste behaviour—An environmental comparison of two packaging alternatives. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyportis, A.; de Keyzer, F.; van Prooijen, A.M.; Peiffer, L.C.; Wang, Y. Addressing Grand Challenges in Sustainable Food Transitions: Opportunities Through the Triple Change Strategy. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2024, 5, 901–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, W.; Qi, L. Stakeholder Pressures and Corporate Environmental Strategies: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, L. Enhancing corporate sustainable development: Stakeholder pressures, organizational learning, and green innovation. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2019, 28, 1012–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnier, L.; Schoormans, J. Consumer reactions to sustainable packaging: The interplay of visual appearance, verbal claim and environmental concern. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 44, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscardi, S.; Colicchia, C.; Creazza, A. Circular economy and food waste in supply chains: A literature review. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2023, 26, 589–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kripalani, M.; Gajjar, H.; Kumar, B. Implementing Extended Producer Responsibility in Organizations: A Bibliometric Review. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2025, 34, 3141–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joltreau, E. Extended Producer Responsibility, Packaging Waste Reduction and Eco-design. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2022, 83, 527–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkelis, A.; Dvarionienė, J.; Denafas, G. The Factors Influencing the Recycling of Plastic and Composite Pack-aging Waste. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindhqvist, T. Extended Producer Responsibility in Cleaner Production: Policy Principle to Promote Environmental Improvements of Product Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweeden, 2000. Available online: https://lup.lub.lu.se/search/ws/files/4433708/1002025.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Hicks, L. Practical Steps for a Transition From ‘Historical’ To ‘Future’ Waste Systems: Individual Producer Responsibility for The Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Directive. Master’s Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweeden, 2004. Available online: https://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/record/1329199/file/1329200.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Eichstädt, T.; Carius, A.; Kraemer, R.A. Producer responsibility within policy networks: The case of German packaging policy. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 1999, 1, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorang, S.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lü, F.; He, P. Achievements and policy trends of extended producer responsibility for plastic packaging waste in Europe. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2022, 4, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracke, R.; De Clercq, M. Implementing the Duty of Acceptance in Flemish Waste Policy: The Role of Environmental Voluntary Approaches. In The Handbook of Environmental Voluntary Agreements: Design, Implementation and Evaluation Issues; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 43, pp. 179–202. Available online: https://biblio.ugent.be/publication/322058 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Ryden, E.; Lindhqvist, T. Strategies for the management of end-of-line cars: Introducing an incentive for clean car development. In Proceedings of the Conference on Towards Clean Transport: Fuel-Efficient and Clean Motor Vehicles, Mexico City, Mexico, 28–30 March 1996; Available online: https://trid.trb.org/view/481424 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Kumar, S.; Fullenkamp, J. Analysis of European Union environmental directives and producer responsibility requirements. Int. J. Serv. Stand. 2005, 1, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. The Producer Responsibility Obligations (Packaging Waste) Regulations 2007, Schedule 2. UK Statutory Instruments 2007 No. 871. 2007. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2007/871/schedule/2/made (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Kollberg, M. Exploring the Environmental Effectiveness of Extended Producer Responsibility Programmes: An Analysis of Approaches to Collective and Individual Responsibility for WEEE Management in Sweden and the UK. Master’s Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweeden, 2003. Available online: https://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/search/publication/1325269 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Margolis, A. Do All Roads Lead to Rome? How Three Process Pathways Contribute to Transformative Innovation in Cross-Sector Partnerships. Bus. Soc. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, L.; Spinler, S. Advancing sustainability in e-commerce packaging: A simulation-based study for managing returnable transport items. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2024, 193, 103868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baca, G.; Reshidi, N. Green Branding and Consumer Behavior, unveiling the impact of environmental marketing strategies on purchase decisions. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2025, 34, 3701–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemann, M.; van de Mosselaar, P.; Perkovic, S.; Orquin, J.L. A method for measuring consumer confusion due to lookalike labels. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2024, 42, 298–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, N.; Ahmad, P.; Toth-Peter, A.; Torres de Oliveira, R.; Acharyulu, G.V.R.K. Developing a circular economy framework for e-commerce packaging materials: A study on behavioural intentions of online consumers. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2024, 34, 982–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simms, C.; Frishammar, J. Technology transfer challenges in asymmetric alliances between high-technology and low-technology firms. Res. Policy 2024, 53, 104937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scopus | Web of Science | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Search Keywords | Packaging, FMCG, Sustain*, Stakeholder, Customer, Consumer | Packaging, FMCG, Sustain*, Stakeholder, Customer, Consumer |

| Search Query String | (TITLE (packaging) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“FMCG” OR “sustain*”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (stakeholder OR customer OR consumer)) | packaging (Title) and FMCG OR sustain* (Topic) and stakeholder OR customer OR consumer (Topic) |

| Date Range | 2019–2024 | 2019–2024 |

| Limitations | English Language | English Language |

| Articles and Reviews | Articles and Reviews | |

| Exclusions | Scopus Subject Areas NOT related to Environmental Sciences or Business, Management and Accounting, or Social Science | Web of Science Subject Areas NOT related to Environmental Sciences or Business or Management or Economics or Environmental Studies or Operations Research Management Science or Social Sciences |

| Database updated on | 24 June 2025 | 24 June 2025 |

| Company Name | Industry | Major Operations | Reporting Frameworks Highlighted | SDGs Mentioned | Name of the Report |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stora Enso | Packaging | Europe, North America | GRI, SASB | 12, 13, 15 | Storo Enso Annual Report 2022 [40] |

| DS Smith | Packaging | Europe | GRI, SASB | 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16 | DS Smith Sustainability Report 2022 [41] |

| Smurfit Kappa | Packaging | Europe, Americas | GRI, SASB, TCFD | 3, 6, 7, 12, 13, 15 | Smurfit Kappa Sustainable Development Report 2022 [42] |

| Tetra Pak | Packaging | Global | GRI | 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 15, 17 | Tetra Pak Sustainability Report FY22 [43] |

| Amcor | Packaging | Global | GRI, SASB, TCFD | 2, 3, 9, 12, 13, 14 | Amcor Sustainability Report 2022 [44] |

| Mondi | Packaging | Europe, Russia, South Africa | GRI, SASB, TCFD | 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, 13, 15 | Mondi Group UN Sustainable Development Goals Index 2022 [45] Mondi Group Sustainable Development Report [46] |

| Nestle | FMCG | Global | GRI, SASB, World Economic Forum Stakeholder Capitalism metrics | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 | Creating Shared Value and Sustainability Report 2022 [47] |

| Unilever | FMCG | Global | WEF IBC, GRI, SASB, United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) | Not specified | Unilever Annual Report and Accounts 2022 [48] |

| Danone | FMCG | Global | Not specified | 2, 3, 6, 8, 12, 13 | Integrated Annual Report 2022—Danone’s Sustainability Performance [49] |

| Reckitt Benckiser | FMCG | Global | GRI, SASB | 2, 3, 5, 6, 13 | Sustainability Insights 2022 [50] |

| Coca-Cola | FMCG | Global | GRI, SASB, TCFD, UN SDG Index, United Nations Guiding Principles Reporting Framework (UNGPRF) | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17 | The Coca-Cola Company 2022 Business and Sustainability Report [51] The Coca-Cola Company 2022 Reporting Frameworks and SDGs [52] |

| DS Smith | Tetra Pak | Mondi | Stora Enso | Smurfit Kappa | Amcor | Coca-Cola | Unilever | Reckitt Benckiser | Danone | Nestle | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Indicators | Sub-Parameters | ||||||||||||

| GHG Emissions | Combined | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | |||||

| Packaging | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||

| Paper | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||

| Recycling | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Employees | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||

| Manufacturing | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||||

| Carbon Footprint | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||

| Logistics & Transportation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||||

| Indirect (by purchases) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||||

| Energy & Fuel | Energy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | |||

| Fuel | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | ||||||

| Renewables | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 | |||

| Emissions to air | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||

| Net energy consumption | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||

| Energy generation | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||

| Electricity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | |||||

| Non-renewables | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||||

| Energy Stewardship | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Green Electricity | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Water | Withdrawals | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 10 | |

| Discharges | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 10 | ||

| Consumption | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ||||

| Emissions to Water | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||

| Water footprint | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||

| Water Stewardship | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||||

| Waste | Waste to landfill | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | |||||

| Hazardous waste | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | ||||||

| Non-hazardous waste | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||||

| Total debris | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Total solid waste | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||

| Waste to Recycling | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||

| Waste to Incineration | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Waste to Compost | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Total Waste Recovered | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||

| Total Waste Generated | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||||

| Total waste reused | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||

| Total waste disposed | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||

| Food Waste | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||

| Material | Raw material inputs | ✓ | 1 | ||||||||||

| Production outputs | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Forest Related | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||||

| Air | Air emissions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | ||||||||

| Environmental compliance | Environmental Incidents/complaints | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | ||||||

| Biodiversity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||||

| Circularity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||

| Packaging | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||||

| Climate | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||

| Regenerative Agriculture | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||

| 13 | 7 | 21 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 20 | 22 | 19 | 15 | 17 | |||

| DS Smith | Tetra Pak | Mondi | Stora Enso | Smurfit Kappa | Amcor | Coca-Cola | Unilever | Reckitt Benckiser | Danone | Nestle | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Indicators | Sub-Parameters | ||||||||||||

| Employees | Employee demographics | ||||||||||||

| Gender | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 11 | |

| Type of Contract | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | |||||

| Turnover | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 | |||

| Age | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 10 | ||

| Designation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 | |||

| Gender Pay Gap | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||

| Regional | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ||||

| Race | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||

| Disability | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||||||

| Employee Engagement | ✓ | 1 | |||||||||||

| Health & Safety | Employees (Incidents, Losses) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 | ||

| Contractors (Incidents, Losses) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||||

| Employee Assistance Program | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||

| Safety Audits | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||||||

| Talent Development | Training & Development | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | |||||