Abstract

Misplaced confidence disguised as competence can lead to broad business blunders. The Dunning–Kruger effect (DKE) is an infamous illusory superiority cognitive bias in which people who perform poorly in certain skills erroneously perceive their task execution as superior to the performance of others. Although it is a metacognitive phenomenon with implications for various domains, it is yet to be directly investigated with managers. The purpose of this study is to bridge the research gap by qualitatively exploring the DKE’s manifestation among managers through 20 semi-structured interviews in agricultural businesses. We found that the DKE manifests at all levels of management; however, it seems that lower-level managers are more susceptible to this cognitive bias. We also present a conceptual framework that highlights the various antecedents and consequences of the DKE, based on our content analysis. This study presents a novel domain affected by the DKE, which was discovered by an unconventional methodological approach. Through the recommendations made, the study also contributes to the SDGs and sustainable leadership and management in agricultural businesses.

1. Introduction

Miscalibrated confidence in place of genuine competence could impede the continuous improvement of managers and their businesses. Contemporary business landscapes place increasingly complex demands on managers. In this rapidly evolving environment, they are tasked with navigating constant change, fostering innovation in turbulent economic climates, meeting the expectations of well-informed consumers, and achieving these objectives while minimising business costs [1,2]. As a result, managers often have to make decisions quickly without considering all relevant factors, which can lead to errors in judgement [3] and potentially have significant consequences for both the business and the managers themselves. In this study, we outline these consequences by conducting semi-structured interviews with managers with varying levels of experience in agricultural businesses. Despite knowing themselves better than anyone else, people tend to struggle with accurately gauging their skill level. This phenomenon, known as the Dunning–Kruger effect (DKE), is an illusory superiority cognitive bias that causes unskilled or less competent individuals to overestimate their abilities and remain unaware of their shortcomings [4].

The purpose of this study is to examine how the DKE manifests among business managers and how it disrupts critical cognitive competencies. We specifically focused on problem-solving and thinking skills through a qualitative inquiry involving 20 semi-structured interviews with managers in South African agricultural businesses. These businesses were chosen because they are typified by environmental uncertainty, seasonal complexity, and changing market conditions, which require adaptive thinking and reflective managerial decision-making [5]. Moreover, they are often neglected in studies involving cognitive biases, even though ineffective decision-making can have dire consequences in this context [6], thereby offering relevance and novelty.

Accurate self-assessment of skills is crucial for estimating the success of future behaviour [7]. Christopher et al. [8] go as far as to proclaim that being affected by the DKE can “break nations,” elaborating that the DKE can impact world leaders, councillors, and other service-oriented leaders to dire consequences since the individuals are charged with making crucial decisions. Considerable research has been devoted to the DKE in various domains and skillsets [8,9,10,11,12,13].

Considering that the DKE has also become mainstream recently, making appearances on television programmes, such as The Recruit in 2022, The Resident in 2021, and You Can’t Fix Stupid in 2014 [14], the DKE may seem to be ubiquitous. However, there is a lack of empirical studies in management sciences. There is also a continuous debate among researchers as to the real reason for the DKE, with the majority of scholars subscribing to the idea that the phenomenon arises because of a lack of self-awareness and metacognition [4,11,12,13,15,16], while others argue that the DKE is simply a statistical feature [17,18,19,20,21].

Despite its mainstream appeal and significant impact on people’s daily lives, the phenomenon of DKE and its consequences remain largely unnoticed by the general public [8] and largely unexplored among managers. While quantitative studies dominate the scholarly discourse, this study highlights the lived experiences of people who experience and deal with the manifestation and consequences of the DKE.

Overall, our findings emphasise the complex nature of the DKE’s occurrence in businesses. Evidently, its impact may depend on certain contextual factors. While it is clear that the DKE primarily presents itself as unwarranted confidence in abilities, this phenomenon has another aspect—underconfidence. Likewise, our findings demonstrate that, in specific situations, a lack of confidence in skills is the predominant manifestation of the DKE.

Our analysis of the interview transcripts confirmed that the DKE exists at all three management levels. Even so, lower-level managers appear to be more susceptible to this cognitive bias. We introduce a novel conceptual framework that highlights the different triggers and outcomes of the DKE in business. Double burden and ego were the most prominent antecedents of the overconfidence aspect of the DKE. On the other hand, the perception that being skilled is common and fear of failure was revealed as the most significant precursor of the underestimation aspect of the DKE. These constructs mainly result in jumping to conclusions, reduced productivity, and excessive caution in decision-making, respectively.

Our study offers insights that promote reflective managerial systems and attentive leadership, which may foster sustainable business growth and resilient decision-making in volatile business settings. Managers who are susceptible to the DKE are less likely to seek continuous learning, are resistant to feedback, and are vulnerable to misinformation [22]. In addition, the DKE reduces managers’ ability to navigate complex environments such as agriculture. [23]. Correspondingly, it advances critical United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 4, SDG 8, SDG 9, and SDG 12. In the context of the current study, addressing the DKE may enhance decision-making, such as sustainable resource allocation and leadership driven by knowledge and humility.

In the remainder of this article, we provide a literature review that explores the role of managers and their competencies in business success, problem-solving, thinking skills, and their blockers. We then highlight cognitive bias as an inhibitor of managers’ skills, specifically focusing on the DKE. This literature review explores this research gap and research question. The next section was the research methodology, where we explained the research design used in this paper, how the sampling was conducted, and the design of the guide used to conduct the semi-structured interviews. Section 3 concludes with how we addressed issues of rigour. After Section 3, we present and discuss our findings and their contributions, research, and managerial implications. This paper concludes with concluding remarks and references to the sources cited throughout the study. Before the reference list, we included the three appendices that describe thematic categories and the formation of these categories. Appendix A describes the themes, Appendix B denotes the formation of the antecedents, and Appendix C shows how the outcome themes were formed.

2. Literature Review

The role of cognitive bias in various contexts has been studied widely. However, the specific focus on the DKE within businesses presents a unique opportunity to expand our understanding of the phenomenon [6]. The DKE, a concept rooted in cognitive psychology, typically addresses the mismatch between perceived and actual abilities. In the context of business management, this phenomenon intersects with theories of leadership and organisational behaviour, offering a novel lens through which to examine managerial competencies and decision-making processes. In the following literature review, we followed a funnel approach to cover preceding publications related to the importance of managerial competencies in modern business, along with the role of problem-solving and thinking skills.

We then discuss the impact of cognitive bias on managers, narrowing the main focus of this article to the DKE. We explore the relevance of the DKE in our study and provide an overview of the known antecedents and consequences of this phenomenon. We conclude this subsection by discussing the research gap and posing our research questions.

2.1. Managers

The importance of managers’ roles in business success cannot be overlooked. Harel et al. [24] assert that managers are crucial for knowledge flow, talent utilisation, decision-making, and innovation promotion in businesses. Moreover, a quantitative study of managers in Portugal’s agricultural industry proved that their demographics, such as education level and age, significantly impact business success [25]. Correspondingly, managers’ competencies have been proven to have a significantly positive impact on the success of small and medium-sized businesses [26]. For this reason, studies on managers should include managers in terms of levels and functions.

2.2. Managerial Competencies

Managerial competence refers to a diverse set of skills, knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours that managers use to be effective in various business settings and leadership positions. Knowledgeable managers are usually highly experienced and/or well-educated and trained, making them so highly skilled at performing their tasks that they do so effortlessly and unconsciously [27]. Three categories of managerial skills remain relevant in contemporary times [16]. These categories comprise human skills, which encompass the ability to interact with and motivate others; technical skills, which relate to the application of specialised knowledge to trade and job-specific tasks; and conceptual skills, which entail the capacity to comprehend concepts, formulate ideas, and implement strategies [28].

Managers are required to have a myriad of competencies to proficiently execute their duties and ensure the efficient functioning of the business. These competencies encompass problem-solving, thinking skills, communication, planning, self-management, self- and other-awareness, decision-making, analytical skills, motivation, global awareness, teamwork, and strategic action, all of which are considered essential [27,29]. Effective problem-solving is arguably the most critical competency for successful business management [30]. Considering its comparative importance, we focused on managers’ problem-solving skills.

2.3. Problem-Solving

Problem-solving can be seen as a process involving mental manoeuvres through steps to attain a predetermined goal. This managerial competency refers to an individual’s ability to masterfully solve problems within a business context [2,27,28,31]. It involves using a structured approach to identify, analyse, and solve problems, as well as making decisions and acting based on the analysis. Managers with exceptional problem-solving competencies can differentiate between algorithmic and heuristic problems, assess alternatives, and obtain answers to questions that they have not yet thought to ask [9]. Truly effective problem-solving processes integrate various other skills, such as self-efficacy, communication, and thinking skills. The effectiveness of managers in this competence is inherently related to their personalities, preferences, and problem-solving styles [8]. In essence, problem-solving competence is the process of finding solutions to complex issues. The resolution of complex issues requires exceptional and apt thinking.

2.4. Thinking Skills

Thinking is the process of considering or reasoning about something, whereas a skill is the ability to do something well. Consequently, thinking skills entail an internal cognitive process that leads to original and productive ideas or conclusions and are often related to intelligence, knowledge, and problem-solving [32,33]. To be successful in their roles, managers must possess various thinking skills, including but not limited to creative, critical, systems and strategic thinking [34]. Managers’ thinking skills, particularly critical thinking in disaster management, aid the problem-solving process by contributing to their evaluation of environmental information, definition of problems, recognition of erroneous assumptions, analysis of arguments, and application of reasoning to draw conclusions [35]. However, even if managers have the required thinking skills, their application during the creative problem-solving process may still be impeded by a variety of contextual barriers.

2.5. Blockers of Problem-Solving and Thinking Skills

Clearly, the significance of creative problem-solving cannot be denied; however, there are both organisational and individual obstacles that can hinder managers’ effectiveness in this area [36]. Common blockers managers face at an individual level include hindrances in the areas that managers face at an individual level, including hindrances in intellect, perception, culture, and emotions [28]. Intellectual stumbling blocks are often caused by mental rigidity and lead to a reliance on past solutions, preventing managers from thinking creatively and embracing new ideas and approaches. Those with perceptual stumbling blocks struggle to perceive their business environment comprehensively, are unable to identify relevant trends and patterns, and often fail to consider others’ perspectives [37]. Cultural stumbling blocks arise from an individual’s social conditioning, leading to a reluctance to embrace change and limit creative intuition [38]. Finally, emotional stumbling blocks can cause individuals to shy away from the unknown due to the fear of failure. These authors found that fear is an antecedent to an implicit bias against creative thinking. Beyond these stumbling blocks, cognitive biases present another layer of complexity and interference with managers’ task execution and decision-making skills.

2.6. Cognitive Bias

Research interest in cognitive bias is not new; scholars have been writing about it since as early as the 1970s [3]. Despite this, there is still a great deal to uncover since approximately 50 well-established cognitive biases can be explored within the context of management. Naturally, research on cognitive bias has mainly been conducted in psychology. However, studying it in business management is important because it can affect how managers perform their tasks [39].

Previous empirical and review articles have highlighted overconfidence as a prominent cognitive bias in business settings [6]. However, it remains unclear what the impact of the overestimation of managers’ ability in relation to the skills of others has on their task execution; that is, what is the impact of the DKE on business managers?

2.7. The Dunning–Kruger Effect

As with other cognitive biases, research relevant to the miscalibration of skill estimates is not new, with studies dating back to as early as 1977, when university professors were found to overinflate their teaching skills [40]. Over two decades later, this phenomenon was investigated more thoroughly and dubbed the Dunning–Kruger effect [10]. The DKE is a type of cognitive bias in which people with low skill tend to overestimate their proficiency due to a lack of self-awareness and inadequate cognitive ability. This results in inaccurate evaluations, erroneous conclusions, and mistakes because unskilled individuals lack knowledge of the scope of the skill and cannot objectively evaluate their incompetence without the necessary metacognition [10]. The DKE has been claimed to be almost ubiquitous in the execution of tasks that are neither mind-numbingly easy nor ridiculously challenging [12].

Since its inception, many empirical studies have established the manifestation of the DKE in various domains. Several authors affirmed its existence in education, particularly engineering, literacy, grammar and humour, by comparing students’ actual academic performance with their projections [4,41,42,43]. Others found it in skills such as emotional intelligence, computing, firearm safety, medical laboratory knowledge, political acumen, and human anatomy [11,44,45,46,47]. While the DKE has been confirmed in various domains, in this study, we sought to explore its impact on managerial skills.

2.7.1. Impact on Managers’ Skills

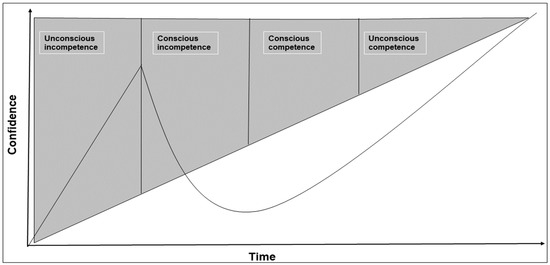

The development of managers’ skills depends on their self-awareness. Managerial competencies are developed in four phases, ranging from unconscious incompetence to unconscious competence [48]. The final stage is achieved when a manager is highly skilled and can perform their tasks effortlessly; however, it takes time and effort to reach this level, and people often overestimate their own competence [13]. The intersection between skills and the DKE is summarised and depicted in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1.

The Dunning–Kruger effect and managerial competency. Source: Adopted from previous studies [10,13,26].

The grey line charts the rise and fall of individuals’ confidence as they develop a skill. Initially, confidence is low but grows quickly as the person develops the skill. Confidence peaks when an individual is unconsciously incompetent and has a false sense of mastery. As they become consciously incompetent, confidence takes a steep downturn but then rises again as the person becomes consciously competent. Finally, confidence peaks when a person can effortlessly perform tasks involving the skill and is unconsciously competent in doing so.

The impact of the DKE on individuals’ daily interactions with their surroundings is significant, and addressing this bias requires awareness. Addressing the DKE can enhance cognitive and decision-making abilities [8]. Relating to mental capabilities, episodic memory has also been found to contribute to the occurrence of the DKE [49]. People often have overinflated perceptions of their skills compared to others, particularly for simple, social, and intellectual tasks [50]. Although the DKE is highly replicable in social psychology [20], it is difficult to detect, especially in those affected by it [10], and how it affects individuals’ self-awareness. Solving cognitive bias relies on managers’ metacognition [50]. Meta-ignorance can be explained by two prevailing theories [38] resulting from intuitive thinking during the problem-solving process [50]. Exploring the literature pertaining to the antecedents of the DKE may provide a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon and its manifestation.

2.7.2. Antecedents

Although the preceding studies did not explicitly focus on determining the antecedents of the DKE phenomenon, we derived a few through our literature review. According to Shu et al. [51], some managers are generally more susceptible to cognitive biases than others. They suggest that prior business- or domain-specific success leads to miscalibrated perceptions of their competence.

It is apparent that the double burden aspect of the DKE is a result of inadequate metacognition [12], which is a notable thinking skill that enables effective problem-solving. A South African study investigated whether most people believe that they are above average, regardless of whether they are skilled or unskilled. These authors achieved their research goal and concluded that deficient metacognition remained the best explanation for the DKE. The analytical thinking of Emeriti students was also affected by the DKE [9].

Meta-ignorance is highly cited as the primary antecedent of the manifestation of the DKE among people [4,6,11,12]. Professionals also tend to rely on familiar patterns and information instead of actively seeking novelty and conflicting sources [52]. This contributes to the cultivation of the DKE in businesses.

Clearly, the antecedents of the DKE will likely vary across contexts and domains, which encourages further research into these factors and various settings. Understanding and ultimately overcoming the DKE is partly dependent on a good grasp of its antecedents. Considering the known consequences of the DKE may encourage the mitigation of its manifestation.

2.7.3. Outcomes

The DKE has recently been found to have a negative relationship with the hypervigilance decision-making style. This means that DKE sufferers rarely exhibit decision avoidance, blame-shifting, and procrastination [8]. Ultimately, individuals do not have the opportunity to enhance their skills when they erroneously perceive themselves to be within the top percentiles [40]. The DKE leads to ineffective environmental scanning and the blinding of sufferers to threats and opportunities that arise through changes in the environment [8]. Unfounded confidence can cause managers to miscalculate risks, leading to detrimental or unprofitable decisions [53]. Overconfidence has been found to cause fallacious policy decision-making practices at the senior level of businesses, especially since miscalibration increases with age and the highest level of education [15]. Unfortunately, even when managers’ miscalibration is pointed out, they double down instead of changing their behaviour [54]. As a precursor to the network summary of our empirical findings. Even though past authors did not present similar models, we integrated our understanding of the existing literature to construct an initial conceptual framework.

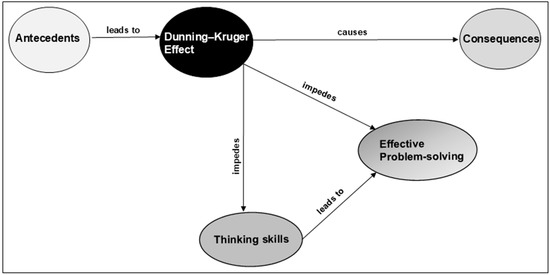

2.8. Conceptual Framework

The antecedents and outcomes are presented in the general framework in Figure 2 below. It serves as the basis for creating our conceptual framework presented in Section 4. By developing this general framework, we aimed to make our findings more readily interpretable.

Figure 2.

A general framework of the manifestation of the DKE. Source: Adapted from various sources [4,6,8,15,35,40,55].

In conclusion, as described and explored in the literature review, various antecedents precede the manifestation of DKE. These have many consequences, including but not limited to impeding thinking skills and problem-solving. Finally, thinking skills are known to lead to effective problem-solving [2]. We expand this body of knowledge by bridging the research gap, as discussed in the following subsection.

2.9. Research Gap and Research Questions

Empirical studies on cognitive bias and managerial skills often include archival records, students, and non-managerial staff [37,56,57,58]. A systematic literature review of the impact of cognitive bias on managers’ skills highlights that middle managers have previously been neglected in empirical studies [6]. The same reviewers found a trend in which previous studies on cognitive bias among managers focused on conceptual skills. They suggest that future scholars follow this trend by exploring the impact of cognitive biases on skills such as strategic decision-making, opportunity discovery, thinking skills, and problem-solving [6].

The DKE is also considered a part of people’s daily lives [8], affecting them in various ways, yet they remain unaware of the phenomenon and its consequences [8]. Apart from unawareness, the academic debate on the relevance of the DKE motivates the current investigation of the phenomenon among managers.

Regarding thinking and intelligence, DKE is apparently not the best explanation for the miscalibration. Gignac and Zajenkowski [17] concluded that studying the phenomenon with nonlinear regressions instead of means yields results contrary to the Dunning–Kruger theory. These authors also posit that when investigating the DKE using quantitative analysis, bootstrapping should be used to confirm that it is not simply a statistical artefact [17]. The authors above seem to contend with the notion of the dual burden given as an explanation of the phenomenon in the seminal DKE paper.

Krueger and Mueller [19] contend that the statistical results supporting the existence of the Dunning–Kruger phenomenon may merely be a regression effect. There is also an argument that the appearance of the DKE may be attributed to measurement errors, as testing estimates against actual outputs can reduce the instrument’s reliability [19,20]. Krajč and Ortmann [18] proposed a model for single extraction, which contradicts the belief that deficient metacognition is the reason for this phenomenon. These researchers argued that subjective judgements do not cause a lack of calibration among poor performers, but rather an objective evaluation that is influenced by a biased knowledge base [18]. More recently, Gignac and Zajenkowski et al. [17] assert that the DKE is simply a statistical phenomenon known as the “better-than-average effect”. These critiques make crucial methodological points and raise legitimate concerns regarding how the DKE is measured in quantitative studies. However, the current article takes a qualitative approach with a focus on uncovering how managers experience and make sense of miscalibration in practical environments.

In an attempt to contribute to the discussion of meta-ignorance, McIntosh et al. [12] proved that the role of metacognition in the DKE is undeniable, except perhaps not as ubiquitous, powerful, or statistically significant as originally proposed in 1999. These authors suggested that meta-ignorance alone is an insufficient explanation for the manifestation of the DKE. They conclude that it occurs because of complex relationships between metacognition, miscalibration, and response errors [12]. This means that more undiscovered factors are likely to lead to the manifestation of the DKE. This adds to the motivation for this study.

Clearly, there are still some detractors of the DKE. Even Dunning and Kruger [10] stated that the DKE may not exist in every sphere of life. Evidently, there is a need for further research on this phenomenon in new domains [12,59]. We believe that this phenomenon also needs to be researched in novel study populations, particularly among managers, since they are responsible for making decisions that determine the direction and success of the business.

We did not find any empirical research on the impact of the DKE on managers. Correspondingly, this study is the first of its kind to delve into DKE in businesses. In addition, little is known about how it affects problem-solving and thinking skills; we can speculate that it leads to poor judgement and decision-making due to a profound lack of unawareness [8,60]. This is a particularly necessary inquiry because the DKE’s existence is thought to be less prevalent in complex skill areas [12].

Competence in intellectual tasks can vary among individuals depending on the specific domain. Therefore, areas of insufficient performance can occur in any setting, and researchers must investigate various contexts [4]. Qualitative research places the study’s participants as the eminent authority on the subject matter and seeks to amplify their voices in their lived experiences of the phenomenon under investigation [61]. Arguably, the best way to achieve this is through qualitative research that relies on the analysis of verbatim quotations.

Since the DKE had not been empirically studied among managers before this study, we explored it by gauging managers’ perceptions of it via semi-structured interviews. This allowed us to gain deep insights into the manifestation of cognitive bias in business settings by engaging real authorities on these matters. To accomplish this, we sought to answer the following research questions (RQs):

- RQ1: Does the DKE manifest among managers?

- RQ2: What are the antecedents of the DKE among managers?

- RQ3: What are the consequences of the DKE among managers?

- RQ4: What is the perceived impact of the DKE on managers’ problem-solving and thinking skills?

In the next section, we discuss the research methodology used to conduct this study.

3. Methods

In this section, we discuss the research design, sample, interview guide, data collection and analysis, and trustworthiness of this study.

3.1. Design, Data Collection Method, and Paradigm

We followed an exploratory qualitative research design to conduct this study and collect the data. This study followed a descriptive qualitative approach [62] with overtones of phenomenology [63] to collect data through semi-structured interviews, and the data were analysed through an interpretive worldview [64]. The reason for implementing this design was that the authors sought to stay close to the descriptions given by the participants and provide straightforward descriptions of the DKE phenomenon. Moreover, the managers who participated in this study are believed to have eminent authority on the subject matter, and we sought to amplify their voices in their lived experience of the impact of the DKE [32,65,66]. In addition, we believe that shared and lived experiences can be meaningfully interpreted. We sought to produce explanatory concepts, models, and strategies based on how managers respond to their interactions and their surroundings.

Using a qualitative approach enabled us to delve into managers’ subjective encounters, thereby yielding valuable perspectives on their self-perception and decision-making procedures concerning the DKE. This particular methodology is especially appropriate for scrutinising intricate phenomena such as cognitive biases, personal experiences, and perceptions that assess pivotal functions [65,67].

3.2. Sample

The study population consisted of South African managers in agricultural businesses. The sample consisted of selected middle managers from five agricultural businesses. We used non-probability, convenience, and judgement sampling to select middle managers because they are likely to be in contact with colleagues (other middle managers), subordinates (lower-level managers), and superiors (top managers) [68]. We deemed this approach appropriate based on the exploratory nature of the research, where we sought conceptual insight, not statistical generalisability. This approach enabled us to require managers at the right managerial level with sufficient experience to answer the interview questions and ultimately allowed us to answer the research questions. Table 1 displays the demographic characteristics of the interviewees.

Table 1.

Sample breakdown.

The following subsection outlines how informed consent was gained in this study.

3.3. Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained in writing upon scheduling the interviews on Google Forms and was reconfirmed verbally before starting each interview. Managers received an invitation letter to participate in the study; the letter included a link that directed them to a webpage that informed them of the purpose of the study and how their data would be used. In addition, the form gathered information necessary to set up an appointment to conduct the interview. After successfully scheduling and honouring the appointments, the interviewer verbally reconfirmed that the managers understood their rights, the purpose of the interview and how their responses would be used.

An interview guide was used to structure the interview process. The interview guide is detailed in the following passage.

3.4. Interview Guide

The interviews were structured around nine open-ended questions designed to capture the managers’ perceptions of the DKE. The participants received these questions and a brief explanation of the DKE before the interview.

The interview guide consisted of four sections, starting with an introduction section (Section A) that outlined the interviewees’ rights, obtained informed consent, expressed gratitude for the participants’ willingness to participate in our study, and reminded them of the study’s objectives. Section B gathered the managers’ perceptions of the DKE. Section C gathered managers’ views on the influence of thinking skills on effective problem-solving (not relevant to this article). The guide concluded by thanking the participants once again and providing them with an opportunity for closing remarks or questions.

3.5. Data Collection and Analysis

Our study obtained ethical clearance from the North-West University (NWU) in South Africa. The corresponding application was received, processed, reviewed, and approved by the Economic and Management Sciences Research Ethics Committee (EMS-REC). The EMS-REC assigned the following ethics number to this study: NWU-00575-22-A4. In order to maintain anonymity, business names and identifying characteristics were deleted during transcription. Participants were given basic pseudonyms according to when the interview was transcribed (for example, Participant 5). To protect anonymity, during member checking, participants only viewed their own de-identified quotes for approval and validation.

Through liaisons at the targeted businesses, we initially identified 21 potential interviewees. During the interviews, the interviewer took notes for probing questions and further analysis. After each interview, additional extensive reflective notes were made to compare and contrast the responses gathered at that stage. Through these reflections, we realised that we had reached saturation and no longer gained any new insights after conducting the 18th interview. We then decided to conduct two additional interviews to confirm adequate engagement [67]. We thanked the 21st manager for their willingness to contribute to our study and informed them that we would not interview them. We used the generic qualitative analysis steps in this study. They were transcription, coding, data reduction, data presentation and drawing, and confirming the conclusions [63].

We identified a reputable service provider and required them to sign a non-disclosure agreement before sending the recorded interviews for transcription. This contributed to our study’s rigour and protected the participants’ identities. After receiving the transcripts, we confirmed their accuracy by meticulously comparing them with the actual recordings. Once we confirmed the accuracy of the transcriptions, we conducted initial (open/descriptive) coding of the margins of the received documents. These documents were sent to two academics who were familiar with the topics under discussion and had extensive backgrounds in qualitative research.

Upon concluding the first stage of peer assessment, ATLAS.ti 23 was used to assist with the content analysis of the qualitative data. As per the original intent of the analysis method, we quantified the qualitative data by counting the frequency of their occurrence during the interviews [32,69,70]. Notably, this was simply a heuristic tool to highlight important patterns across different datasets, not for the purpose of statistical generalisability. The presented frequencies support a thick description instead of replacing it. The purpose behind this was rooted in the requirement of analytic transparency and not numerical validation. ATLAS.ti was also used to visualise our findings. Tesch’s eight coding steps were used for data reduction [71]. Various codes were created and combined to form the thematic categories of our study. These categories are described in Table A1 (Appendix A) and include main categories, categories, sub-categories, and secondary sub-categories.

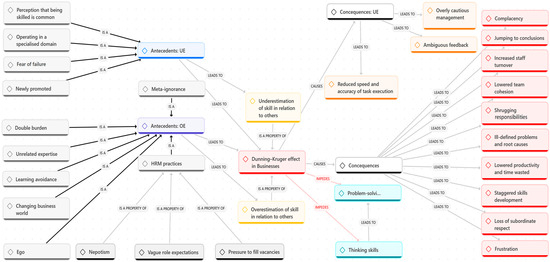

The findings and quotations in this article are presented in a fashion similar to those of previous studies [33,72]. Moreover, we summarised the interactions between these categories in the network function in ATLAS.ti to create a conceptual framework for the manifestation of the DKE in businesses. This framework is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Network summary of the antecedents and outcomes of the Dunning–Kruger effect in businesses.

Before writing the results and drawing conclusions, we sent the final codes (axial/closed codes) for the second and final stages of the peer assessment. All additional measures were implemented to promote credibility, reliability, external validity, trustworthiness, and rigour [73].

3.6. Rigour

The interviews were conducted in the participants’ natural settings, where the phenomenon under investigation occurred. Through extensive field notes, we can attest to prolonged engagement. To ensure the accuracy of our interpretations, we employed member checking by soliciting reviews and comments on our findings from the 20 managers who participated in our study. We advanced our study’s transferability by reaching and confirming saturation and comparing perceptions from different demographic groups. Transferability is further supported by the description of the context, transparent sampling criteria, and inclusion of diverse organisational and functional roles. Furthermore, dependability was promoted through two stages of peer examination [63].

In addition to bracketing, we stored all noteworthy documentation and correspondence with liaisons and participants to form an audit trail that promotes confirmability. Finally, we remained faithful to the participants’ authentic opinions by conveying them verbatim, presenting them as unedited for grammar, and untranslated for those who elected to be interviewed in their native language [73]. After presenting the verbatim Afrikaans quotes, we provide translations to benefit the readers and the reviewers. A language expert at the Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences at the North-West University performed the translations. The inclusion of unexpected and unconventional positive outcomes of the overconfidence facet of the DKE further attests to the depth of our analysis of the transcribed interviews. We also included the perceptions of managers who have not experienced any facet of the DKE at any managerial level within their businesses.

4. Findings and Discussion

Drawing upon theories in cognitive psychology, such as metacognition and self-assessment accuracy, this study situates the DKE within a broader theoretical framework. This approach enables us to explore the interaction between cognitive biases and managerial decision-making. In this section, we present our findings by answering our research questions. We begin with a demographic summary of the respondents and then discuss the findings.

4.1. Demographic Summary of the Respondents

This study focused on agricultural businesses. Table 2 below summarises the demographic particulars of the managers who participated in this study.

Table 2.

Participant demographics.

The majority (70%) of our interviewees were males within the operations department (six managers), mostly with between 16 and 20 years of managerial experience (six participants) and residing in the North-West Province (45%) of South Africa.

The findings presented in this study provide additional credence by emphasising the perceptions of highly experienced managers. Moreover, although not exhaustive, the participating managers covered a significant geographical representation of South Africa.

4.2. Dunning–Kruger Effect Manifestation in Businesses

Our analysis of the managers’ responses leads us to deduce that the DKE does indeed manifest in businesses in various ways. The DKE is usually expressed as overconfidence in one’s abilities and underconfidence in skills in relation to others.

4.2.1. Overestimation (Overconfidence) in Abilities

Both facets of the DKE exist in businesses. However, since the inception of this phenomenon, researchers have been mainly interested in the DKE, causing overconfidence in abilities. Notably, we found that most managers experienced this aspect of the DKE in their businesses.

“I think the place where it mostly exhibits itself is whenever you give a task to someone that’s doing the task for the first time…”Participant 4

“…I think to a large extent, we do that sort of behaviour in the business, and that comes down to the Dunning–Kruger effect in my personal view.”Participant 7

“But that isn’t that what all managers do?”Participant 8

“From a Payroll perspective and HR perspective, I say to great extent…”Participant 10

“It does exist in our business…”Participant 12

“I made some notes just after lunch before the interview, so I would say I did go through the bias and, I would say, to a very large extent.”Participant 17

One manager reported that the phenomenon only exists to a relatively small extent.

“It is there to some extent to some managers…”Participant 20

Some respondents experienced this phenomenon only when interacting with or observing their subordinates, whereas only one perceived it as affecting their colleagues at the middle management level.

“Ja, ek dink verseker dit is verseker deel van ons besigheid. Ek sien dit baie met tak bestuurders wat ek mee werk…”Participant 13

This Afrikaans verbatim quote was translated as follows: Yes, I think for sure it is certainly part of our business. I see this a lot with the branch managers I work with.

“I think it has a large impact in the lower job grades, because it definitely does exist…”Participant 19

“…they don’t have the specific knowledge or even expertise to complete certain tasks or to reach deadlines with those certain tasks. It is definitely frustrating to see because they work with me, they are unfortunately paid the same as me but they don’t have what it takes to do the work to perform the tasks and it’s extremely frustrating to work with, it’s extremely frustrating to work with these people however they do always where they always feel overconfident in their abilities…”Participant 1

Our findings highlight the prevalence of the main aspect of the DKE in business. The participating managers in our study experienced unfounded confidence in their actual skill levels. The DKE seems to significantly affect inexperienced individuals; therefore, executives should bear this in mind when delegating tasks. The notion that “all managers” are susceptible to the DKE, as highlighted by Participant 8, is particularly concerning since the DKE is traditionally not thought to be ubiquitous [6,10,74]. Correspondingly, Participant 20′s views show that there is variability in how this phenomenon may manifest among various managers within the same business context.

4.2.2. Underestimation (Underconfidence) in Skills

Although researchers tend to focus on the overestimation of the competence aspect of the DKE, surprisingly, some participants reported experiencing an underestimation of skills when compared to others in their respective businesses.

“To be honest, at the company I work for and especially the department I work in, I don’t think that people in general overestimate themselves; in fact, I think most of the people that work in my department underestimate themselves.”Participant 3

“Nee, ek dink nie dit gebeur te veel nie, ek sal eeder sê mense onderskat hulle abilities.”Participant 9

This Afrikaans verbatim quote was translated as follows: No, I do not think it happens too much, I’d rather say people underestimate their abilities.

In one instance, we noted a participant who had experienced both sides of the DKE proverbial coin.

“…I think it actually exists in my perception on two levels. My first exposures, when you’ve given me the definition of what the Dunning–Kruger effect is, meaning that you overestimate your capabilities or maybe even underestimate. It was a few years ago where I, as a manager, had a performance review on employees, and I saw two individuals, according to my view, where they had the same level of academic experience or qualification of knowledge, they had the same level of years’ experience, but their performance levels were different…”Participant 3

Overall, our findings underscore the multifaceted nature of the DKE’s occurrence in businesses. It is clear that its impact may depend on certain contextual factors. Furthermore, our findings show that, in some contexts, underconfidence in skills is the prevalent manifestation of the DKE. Participant 3′s recount of the performance review process presents a nuanced take on the two ways that the DKE can exist in businesses. Their account further highlights the complexity of the DKE manifestation. Undoubtedly, awareness of self and others is an important factor in the manifestation of the DKE among business managers.

Underestimating skills is a known trait among experts [48]. This does not imply that all managers are experts; however, they tend to be highly informed due to their education and experience. These findings imply that the DKE extends beyond overconfidence, as it can also encompass scenarios in which people underestimate their capabilities or fail to acknowledge their true potential. These findings also highlight the need for a more comprehensive understanding of the DKE’s multifaceted nature and its impact on managers’ performance, self-perception, and behaviour within business settings.

4.3. DKE Impact on the Three Levels of Management

When delving into how the DKE impacts managers at various managerial levels, we discovered that top management seems to be the least affected by the DKE.

“…I would say it’s not as evident in my superiors.”Participant 4

“No, I don’t think so. I report to the CEO. So, he’s a CA, a chartered accountant.”Participant 6

“I have to say that I have not yet had this type of problem from the superiors.”Participant 16

Some participants found it challenging to comment on how the DKE impacts top management.

“…that’s a bit difficult because I have to look at it at subordinate level.”Participant 4

“Maybe if it was one of their peers, maybe I would’ve seen it to a stronger degree, but I can’t say.”Participant 5

“…that’s a difficult one to answer because they also send you stuff to read, but they don’t interact that much with you…”Participant 8

This is likely because they did not have as much interaction with them as the managers, who could easily reflect on this matter, as mentioned by Participant 8. Alternatively, we may consider some level of discomfort in speaking on the phenomenon at this level, since they report to these individuals in their respective businesses. This may be the case even though all attempts to ensure anonymity were made. Other authors support this assessment, finding that subordinates often find it difficult to reflect on their superiors’ behaviour due to a sense of loyalty toward their managers and the hierarchal nature of businesses [75].

On the other hand, a few managers perceived their supervisors as susceptible to the DKE.

“I think sometimes there is a feeling that some superiors always think they know best…”Participant 3

“I think especially the higher the management level I would say you can increasingly see it…”Participant 5

“Nobody will ever be as good, or as smart. So, definitely. I definitely see that in one of the superiors.”Participant 7

Our analysis shows that managers perceive their colleagues and other middle managers to be somewhat affected by the DKE.

“…I have definitely seen this amongst colleagues…”Participant 1

“I think due to the age and experience of people you tend to see it in a lesser way amongst my peers, but you tend to see it more with the young people coming through.”Participant 12

“I think the challenge that we have is ego…”Participant 20

Additionally, Participant 20 believed that middle managers were more susceptible to the impact of the DKE.

“I think with the subordinates it’s far better than with people that are on the same level with [me]…”Participant 20

Conversely, one participant was of the opinion that higher levels of management are more susceptible to the DKE than lower levels are, probably because lower-level managers enjoy the benefits of supervision.

“…the subordinates, I would say to a lesser degree, because they are still unsure and still learning and still strongly relying on the guidance of their supervisors.”Participant 5

Notwithstanding, other managers see the DKE affecting lower-level managers more than it affects higher-level management within businesses.

“So, definitely amongst the subordinates, definitely that effect amongst my subordinates more so through the subordinates than the colleagues…”Participant 1

“But I would say, I see it especially in young sort of junior managers with little experience, which was for short period in roles.”Participant 12

“From my perspective, no it doesn’t exist. Yes, there is the exception of a junior…”Participant 14

Therefore, our findings indicate that the DKE’s manifestation across the three management levels is uniform in businesses. In addition, although there is no consensus on this issue, lower-level managers seem to be the most susceptible to the DKE.

4.4. Self-Reported Manifestation of DKE

When self-reporting the manifestation of the DKE, the participating middle managers had the levity and self-awareness to admit its existence.

“…if somebody asks you how to do something, say yes and learn how to do it later… Yes, it does exist in me as well; I’ll admit that.”Participant 1

“I always think I know more than I do, and I accept when I’m wrong, but I always fight till the end to make my point.”Participant 5

“I do yes, I do use it sometimes when I don’t have knowledge …”Participant 8

“It does, I think it exists within everyone. We all think we know a lot more than we actually do.”Participant 19

Some managers self-reported the DKE in terms of underestimating of their skills.

“…I definitely think I underestimate myself sometimes…”Participant 3

“Well I am also guilty in the parts of sometimes I need to do a bit of self-investigation by initially just think this is maybe a little bit over my head, I might just take a step down then if when you go and do it and see—evaluate yourself and say, okay but listen, man, you are up to this, give it a go.”Participant 11

“…I do personally find myself doubting my own capability…”Participant 17

These self-reports exhibited a certain level of maturity and self-reflection within the middle management group. This well-rounded self-awareness indicates that these managers actively monitor and evaluate their own decision-making and self-perception. Conversely, Participant 8 may view the overestimation aspect of the DKE as a tool, stating, “I do use it sometimes…” could indicate why sufferers do not address this cognitive bias. In addition, it may reveal a whimsical perception of its manifestation in the self, whereas observing it in others does not receive the same amount of goodwill and grace.

4.5. DKE’s Non-Existence in Businesses

Some managers have not witnessed the impact of DKE in any form on their businesses.

“…I think overall we’re at a good level and I think we’ve got the right people in the right positions.”Participant 6

“No, not at all.”Participant 18

These managers are a minority group. Most participants noted the phenomenon’s existence in one form or another, in either their superiors, colleagues, subordinates, or themselves. Even though these managers are a small minority, their opinions are included due to our conviction that the managers are the eminent authority on their experience of the manifestation, or rather, in this case, non-existence of the DKE phenomenon in business. Moreover, their inclusion contributes to the depth and completeness of our content analysis.

4.6. Answering RQ1: Does the DKE Manifest Among Managers?

Yes, our analysis indicates that although participants do not unanimously perceive the DKE’s manifestation in their workplace, the cognitive bias certainly does exist in the business world. The existence is in both the overestimation and underestimation of skills. It also affects managers at all levels of management; however, lower-level managers seem to be more susceptible to it than those at higher levels. Our findings cement business management as a domain affected by the DKE.

This phenomenon affects businesses through managers’ competence in task execution. Therefore, in the next sub-section, we delve deeper into our qualitative data to illustrate a conceptual framework that uncovers the antecedents and consequences of the DKE in businesses.

4.7. Conceptualising the Impact of the DKE in Business

We formed main thematic categories, categories, sub-categories, and secondary sub-categories through content analysis. The tables that describe and deconstruct the formation of these categories can be seen at the appendices. In Appendix A, we describe each category and provide a comprehensive insight into the intended meaning of each category formed.

Appendix B (which is made up of Table A2) and Appendix C (which is made up of Table A3) consist of two main categories: antecedents and outcomes, respectively. We indicate the prominence of the various sub-categories, which create the categories and main categories, by providing a frequency column that denotes the number of instances in which the participating managers mentioned something that was interpreted and categorised accordingly. To provide further clarity in our interpretation of the qualitative data and to emphasise the voices of our responders, we also highlighted example quotes from the transcripts that built all the thematic categories.

Appendix B shows primary Category 1, which represents the factors that occurred before the development of the DKE. Following this, we present a table that illustrates the creation of main Category 2, which represents the effects of the DKE on businesses.

To aid in the comprehensive understanding of the impact of DKE on businesses, we condensed the thematic categories found in the tables in Appendix B and Appendix C by developing the conceptual framework below. The framework presents a snapshot of the formation of various interactions between the categories. We developed Figure 3 using the network tool in ATLAS.ti 23 and our interpretation of the transcripts. It can be seen as our interpretation of the nuanced associations between the facets, precursors and consequences of the DKE. The framework can be confirmed or dismissed by future empirical scholars.

4.7.1. Antecedents of the Manifestation of the DKE in Businesses

As discussed throughout this article, the DKE manifests either as overconfidence in abilities in relation to others by incompetent individuals or as underestimation of skills when compared to others (by highly competent people) [4,49].

As it concerns overconfidence in skills, we deduced seven factors that precede the occurrence of the DKE in businesses. Due to the frequency of its mentions during interviews, the antecedent that stood out the most was the double burden. Similar to our findings, unawareness of the scope of a domain or skill is acknowledged as a primary factor leading to the DKE [4].

“… most certainly, people that I can think of that when you ask them about anything, they are the expert according to them, and they’re not open for debate on whether they know or not. They just believe they are.”Participant 5

“And they tend to say they apply past knowledge but sometimes they don’t have enough [knowledge]…”Participant 12

“It does show itself among colleagues, especially when they get involved in job skills that they’re not very ‘au fait’ with. You know, you often get people that actually have no knowledge of something that will tell you how to do your job.”Participant 19

Likewise, a lack of depth perception in competency drives overconfidence, which can stem from some people being naturally egotistical. The ego may also exacerbate managers’ susceptibility to the DKE by leading them away from continuous learning and the advancement of metacognition [32]. Ego can add to the distortion of self-perception when the ego is inflated. When ego and overconfidence thrive, the DKE manifests more easily [76]. In addition, the association between ego and inflated self-perception aligns with earlier works [8,77]. The DKE and high self-perception associated with ego also tend to be more prevalent in crucial industries [8,78]. Correspondingly, we deduced that managers who are averse to learning and vulnerable to meta-ignorance contribute to the manifestation of the DKE in business settings. Although this finding can be considered anecdotal, it was consistently observed across multiple interviews.

“I think the challenge that we have is we still have ego…”Participant 20

“…those people all are really arrogant…”Participant 5

“And maybe not always look at it critically enough, and they don’t critique the thinking, you know, in different ways.”Participant 7

“… it affects the remaining open to continuous learning as well. If you think you know everything, why listen to others?”Participant 12

To a lesser extent, the pace at which the business world is continuously changing and the notion that expertise in unrelated fields can be extrapolated to problem-solving competence and thinking skills lead to the DKE in businesses. This extrapolation of unconnected expertise is also associated with a seemingly unrelated cognitive bias, known as the halo effect [78]. Unlike the DKE, which centres on the self-misperception of ability, the halo effect is an attribution bias rooted in observer perception.

“… but I think life in general has just increased the pace of exposures and decisions that you have to take…”Participant 16

“…their knowledge are really limited to what they do, and, but those people all are really arrogant with regards to everyone else’s work…”Participant 15

Finally, human resource management factors, such as vague role expectations, pressure to fill vacancies, and nepotism, have been found to drive the occurrence of the DKE in business settings.

“I think the misunderstanding on skills is based on misunderstanding on maybe not clear on the descriptive or the requirements by the employer.”Participant 2

“…so we’ve got our operations manager position vacant, it needs to be filled…”Participant 17

“…managers are purely brand new to the company have been approached through nepotism, and they manage people, and through that they don’t know what objectives would need to be reached…”Participant 1

To the best of our knowledge, these factors, along with a disposition to ego, learning avoidance, the pace of change, and unrelated expertise, are all novel empirical findings pertaining to the antecedents of the DKE. This provides new knowledge on how the main DKE facet develops, particularly within the previously unexplored domain of business management. In addition, an unexplored link between the halo effect and the DKE has emerged as a potential avenue for future research.

Regarding the DKE’s underestimation of skills, we found that the perception that being skilled is common is a profound precedent of the DKE. This factor is also an accepted antecedent in the existing body of knowledge [13]. This perception can also be linked to false consensus bias [60]. This cognitive bias overestimates social agreement because individuals falsely assume that others share their beliefs. It differs from the DKE by focusing on social norms rather than personal competence [3].

“I’ve got the expectation that people know exactly what I’m meaning when I ask for something…”Participant 19

“En ek sê ʼn ou verloor bietjie kontak met iemand wat dalk dink in elk geval hy weet meer as wat jy weet, jy weet, of dalk aan neem jy weet wat jy weet.”Participant 13

This Afrikaans verbatim quote was translated as follows: And I say a guy loses touch with someone who might think anyway he knows more than you know, you know, or maybe assumes you know what you know.

Another antecedent of this manifestation of the DKE is fear of failure, which limits managers’ optimal performance due to an aversion to appearing inadequate among subordinates, peers, and supervisors. This antecedent can be seen as uncertainty in managers’ ability to satisfy expectations [38]. People who are more aware of the scope of their domain can be overly aware of their limitations and have more grounded perceptions of their skills to avoid underperformance [78], causing underconfidence in managers who are susceptible to this facet of the DKE. This precursor to the DKE is related to the emotional personal stumbling block [10,28]. Notably, this occurrence is based on managers’ perceptions rather than the researcher’s observations. Moreover, this finding is supported by Aparna and Menon [38], who linked imposter syndrome and fear of failure to suppressed self-perceptions in management settings. Imposter syndrome occurs when objectively competent individuals feel inadequate and fear being exposed as incompetent. In contrast, the underconfidence facet of the DKE is typically associated with the modesty that comes with conscious competence [27].

“…you under-promise because you are afraid of failure. You sometimes make 200% sure…”Participant 12

“I don’t like letting people down…”Participant 11

“I would rather say that they don’t always believe or not always sure that they are on the right track and its sort of confirming “am I doing what you want me to do?”Participant 3

Our analysis also reveals that operating in a specialised domain and being newly promoted are antecedents of the underestimation of the DKE’s skill manifestation in businesses. However, these two factors were not as frequently mentioned during the interviews.

“They are all very skilled and educated people and we work in an audit environment.”Participant 3

“…this is a new position within [the business] and it’s on the job learning position. So, I go out of my way to upskill myself with regards to this position…”Participant 20

Functioning in a highly specialised career can decrease an individual’s awareness of how rare true unconscious competence is, which can be seen as a notable antecedent of the DKE. Likewise, recent promotions can feel undeserved because they ignore the merits of the promotion and cause a lack of confidence in their skills. This is also potentially related to the impostor syndrome, which is the polar opposite of the primary facet of the DKE [79].

4.7.2. Answering RQ2: What Are the Antecedents of the DKE Among Managers?

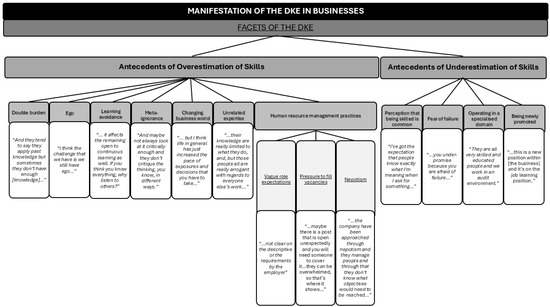

As depicted in Figure 3, each antecedent type leads to its respective aspects of the DKE in businesses, and each facet is a property or descriptor of the cognitive bias. Double burden and ego are the most prominent antecedents of the DKE’s overestimation facet. In contrast, the underestimation aspect of the DKE is mainly caused by the perception that being skilled is common and the fear of failure. To further synthesise these findings, we have illustrated the formation of the thematic categories in Figure 4 below. The organisational chart depicts the antecedents of the manifestation of the DKE, including example quotes from the participating managers’ transcribed interviews.

Figure 4.

Categorical formation of antecedents of the Dunning–Kruger effect in business.

4.7.3. Outcomes of the DKE in Businesses

Through in-depth content analysis, we observed ten consequences of the primary descriptor of the DKE in business settings. Three resulted from underconfidence and, unexpectedly, two perceived benefits of this phenomenon. In the following passages, we discuss these findings in descending order of frequency.

Jumping to conclusions is a concerning consequence of overconfidence in one’s problem-solving competency. Since sufferers of the DKE are unaware of how uninformed they are, they tend to rush the problem-solving process by making quick decisions [24].

“… when you find that stumble block, you problem-solve quickly…”Participant 7

“As I said, they tend to jump to conclusions.”Participant 12

“…shoot from the hip and show everybody what she’s done, and it’s actually incorrect.”Participant 19

This behaviour may undermine environmental responsibility and future planning, particularly in areas that are sensitive to resources, thereby jeopardising sustainable practices.

The overestimation of skills in relation to others also results in erroneously completed tasks, which must be rectified or disregarded entirely. This inefficiency causes time wastage, which lowers overall productivity.

“So, we do what we do, but I mean it is counterproductive…”Participant 5

“My problem is I can never say no to people and that puts me in a very bad situation sometimes trying to keep up to date.”Participant 10

“…over-believer he will go and do [it] the way, and he will mess it up, and he will need to step back and then do it over again.”Participant 11

Long-term inefficiencies diminish organisational productivity and increase operational costs, which in turn weaken financial viability and the ability to withstand challenges.

We also found that complacency, where managers become closed to suggestions, are comfortable in their unconscious incompetence, and are stagnant in their development, is a notable consequence of the DKE.

“…we’re not in a position where we can make suggestions to do things better, because they know better, but they don’t.”Participant 5

“… the people that I am on the same level with have been with within [the business] for so long so now they feel like they are too comfortable.”Participant 20

This lack of progress hinders ongoing improvement and innovation, which are key factors for economic and social sustainability.

The fourth consequence, shrugging responsibilities, shows that the DKE can cause blame-shifting and a reluctance to show initiative. If not addressed, this can contribute to a business culture that is devoid of accountability and innovation.

“They’re also blame-shifters. There’s always another scapegoat. They’re never wrong. They’re never the ones who take responsibility… ”Participant 5

“…certain activities that are given to them is passed on to people that know how to do it”Participant 10

The fifth and sixth consequences of the DKE uncovered in our analysis were reduced team cohesion and ill-defined problems. Overconfidence can alienate those around them, impact their attitudes, and ultimately hinder team dynamics and collaboration. The DKE also impedes effective problem-solving by causing inadequate problem and root-cause exploration and identification.

“So, we are a service division that delivers to this department, and the people refuse to work with them just because of the way they do things…”Participant 5

“…it leads to wrong decisions, because they don’t delve into the problem enough… they don’t really get to the root cause if they think they’ve got their answer.”Participant 12

This may cause managers to focus on irrelevant problems or solving problems that have little impact on the longevity of the business.

The remaining consequences deduced from managers’ experiences and perceptions were increased staff turnover, staggered skill development, loss of subordinate respect, and frustration. Misplaced overconfidence may decrease staff retention, skill development, and mutual respect, along with being a source of frustration for others.

“…our staff turnover was quite high… it’s actually a very big challenge…”Participant 15

“So, there isn’t any continuous training or continuous improvement expected from their side as well.”Participant 20

“…they losing their subordinates’ respect because of the decisions that they making…”Participant 1

“…it makes me really upset. It makes everyone upset.”Participant 5

This discourages talent development, decreases thought diversity, and undermines organisational culture, ultimately compromising human capital and long-term sustainability.

Together, these consequences disrupt an organisation’s capacity to learn, develop, and function responsively over time. By making a direct connection between cognition and sustainability challenges, this model contributes not just to psychological theory but also to the evidence-based development of sustainable business practice.

Likewise, we found three consequences of managers’ underconfidence in their skills. Firstly, it makes them overly cautious, which has been linked to squandering opportunities in previous studies [8,12].

“I think most of the time there is a feeling that they want to really make sure that they on the right track with the work that they doing and I often have to reassure them…”Participant 3

Moreover, this aspect of the DKE was found to reduce the speed and accuracy of task completion as well as lead to managers being provided with ambiguous feedback. This means that an underestimation of skills can make managers work slower due to overthinking. Similarly, in an attempt to seem non-confrontational, sufferers of this facet of the DKE may provide unactionable feedback or even withhold it altogether [56].

“I definitely have to think if somebody over or underestimates themselves it can have a huge effect on how you need to manage people or the speed at which tasks are completed and completed accurately.”Participant 3

“…they would seldom help people and say: “You are wrong”, Maybe they would make suggestions, but in such a subtle way…”Participant 5

This may be harmful in any industry which demands timely and accurate decisions. If these outcomes remain unaddressed, they will impede sustainable development on the business level as well as the personal level (among managers and their subordinates). This would be a waste of human potential and business resources.

Clearly, the DKE is detrimental to businesses, leading to dire consequences. Notably, the consequences of overestimation are more numerous and arguably more devastating. Additionally, our analysis reveals that this phenomenon is particularly detrimental to solving heuristic problems. This accentuates the need for awareness and corrective actions against the manifestation and results of the DKE in businesses [80].

“I’d say new problems yes, not day-to-days, ’cause day-to-days is like a part of who you are by now, but new problems, yes, ’cause then you might overestimate yourself…”Participant 4

Surprisingly, we uncovered positive perceptions that result from the manifestation of the DKE in businesses. Although there were only two sub-categories to the three instances of this type of outcome, they are noteworthy, nonetheless. Overconfidence in one’s managerial skills may result in one being propelled into a place where they can perform beyond their limits [81,82]. At least one participant found that to be inspirational.

“So sometimes just believing in yourself, and in your abilities, without really knowing, that can push you to complete a task that might have looked very difficult in the beginning.”Participant 7

“…as iemand hom oorskat dan is dit mos eintlik goed, dan gee hy mos nou meer as wat hy het, wat hy eintlik kan gee.”Participant 9

This Afrikaans verbatim quote was translated as follows: If someone overestimates themselves, then it is actually good, then they arere giving more than what they have, more than they can actually give.

“…they don’t have the expertise, experience or knowledge to complete the certain tasks even though they do feel confident in them, they feel that they are up to the task up to the challenge and everything which is sort of inspirational to see.”Participant 1

Overconfidence that leads to functioning beyond managers’ perceived limits might be precisely what is needed to challenge unsustainable status quos and develop solutions that will benefit a multitude of generations to come. Unfortunately, it may also create overreaching, burnout and inefficient resource allocation.

4.7.4. Answering RQ3: What Are the Consequences of the DKE Among Managers?

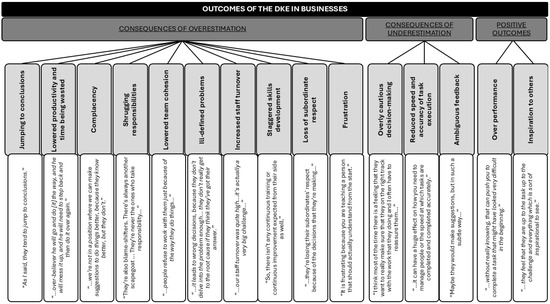

There are many consequences of multi-faceted DKE in businesses. Overconfidence mostly leads to jumping to conclusions, lowered productivity, wasted time, complacency, and shrugging responsibilities. Underestimation of skills leads to overly cautious decision-making, reduced speed and accuracy of task execution, and ambiguous feedback. Interestingly, there are positive outcomes from an overestimation of abilities, such as overperformance and inspiring others. The inclusion of these unexpected and unconventional findings is a testament to the depth of the content analysis. In addition, we sought to further synthesise these findings by illustrating the formation of the thematic categories in Figure 5 below. The organisation graph exhibits the outcomes that arise due to the manifestation of the DKE in business settings. The image also includes direct quotations from the interviews held with the participating managers.

Figure 5.

Categorical formation of outcomes of the Dunning–Kruger effect in business.

4.7.5. Answering RQ4: What Is the Perceived Impact of DKE on Managers’ Problem-Solving and Thinking Skills?

Ultimately, with prominent consequences such as jumping to conclusions, complacency, ill-defined problems and root causes, reduced speed and accuracy of task execution, and overly cautious management, we find it apparent that the DKE impedes managers’ thinking and problem-solving skills in a multitude of ways. It also seems like managers are more susceptible to the DKE when solving novel problems.

5. Managerial Implications and Recommendations

The findings have important implications for managers, leadership developers, and organisational strategists who are committed to pursuing sustainable business. Dealing with the DKE is not only a psychological exercise but rather a strategic necessity that has consequences for all managerial decisions. The recognition of limitations may decrease stagnation, improve the likelihood of innovation and sustain the long-term economic viability of businesses. Specifically, the study highlights the extent to which the DKE erodes key managerial competencies and skills (like problem-solving, critical thinking, and self-assessment) that drive organisational resilience and long-term profitability.

Firstly, this research illustrates that distorted self-assessment, whether it appears as excessive confidence or a lack of confidence, results in poor utilisation of thinking skills and decision-making. Managers with excessive confidence tend to reach conclusions too quickly and operate inefficiently, while those lacking confidence may delay action, leading to disengagement and missed opportunities. These behaviours not only diminish individual effectiveness but also stifle collective innovation and sustainable progress.

Moreover, the widespread nature of the DKE at all levels of management, although most pronounced at the lower tiers, indicates that organisations need to embed metacognitive awareness into their managerial training programmes. Development initiatives should emphasise reflective practices, humility in leadership, and structured feedback mechanisms that assist individuals in calibrating their self-perceptions more effectively over time.

Also, leadership development models should be broadened to prioritise cognitive resilience as a primary goal. This involves fostering the ability to handle complexity, challenge assumptions, and adapt one’s thinking in light of new information, skills that directly support sustainable decision-making and ethical organisational management.

In addition, companies should cultivate environments of psychological safety and ongoing learning, where cognitive biases can be openly discussed, examined, and mitigated. This approach will not only diminish the impact of the DKE but also encourage more inclusive, flexible, and sustainable leadership practices throughout the organisation.

In general practice, the findings of this study emphasise the need for more sophisticated managerial training programmes that address cognitive biases, such as the DKE. Such programmes should not only raise awareness about the existence and effects of the DKE but also equip managers with tools to self-assess and adjust their perceptions of competence.

To alleviate the effects of the DKE, regular feedback sessions, ongoing education, and training are essential. Managers should be encouraged to cultivate curiosity and engage in thorough self-investigation. Resource allocation toward accountability, leadership programmes, and interdepartmental interactions is imperative to combat complacency and groupthink.

We also suggest that businesses create platforms or communities internally, where managers can exchange their experiences, challenges, and best practices, fostering mutual learning and awareness of the self and others. Furthermore, they should consider acknowledging and incentivising managers who actively engage in introspection, seek feedback, and are willing to learn and develop. Incorporating 360-degree feedback assessment policies involves input from superiors, colleagues, subordinates, and self-evaluations to offer a comprehensive perspective on managerial competence. Furthermore, talented managers should continuously update competency models and job descriptions to align with changing industry trends and organisational requirements, ensuring that managers clearly understand their roles and obligations.

Moreover, simulation-based learning and cognitive debriefing can be used to expose managers’ susceptibility to the DKE in real-time, thereby presenting the opportunity to deal with miscalibration in a low-risk context. Adopting such practices in regular managerial training can facilitate the institutionalisation of cognitive resilience and long-term business sustainability.

Notably, this article raises awareness regarding the consequences of the DKE. This is crucial because the DKE is propagated by individuals’ unawareness of its existence and, more importantly, its influence on their behaviour. In addition, the DKE impedes managers’ ability to reach their true potential because they are blissfully oblivious to the room for improvement. The impact of this cognitive bias is that it creates an illusion that there is no need for further acquisition or development of knowledge and skills.

6. Contributions, Limitations, and Research Implications