1. Introduction

The space surrounding us is filled with objects that grow during the stages of the urban development of the city. Along with changes in the urban cultural landscape, our perception is also transformed: places of particular importance remain, while around them space takes on a new expression. Sacred objects are assigned the role of architectural dominance in the space that surrounds us. It is difficult to determine how a church is perceived through the prism of its height, its visual impact, or its compositional creation, or maybe it is the shape that emphasizes and distinguishes its role for the local environment. Regardless of the perception, the word dominant is always perceived as important, signifying power [

1], and in the aspect of urban space it determines the importance of place. In the theological sense, historic church buildings are a public place, so everyone is responsible for their preservation [

2].

Despite the growing functional diversity of space and cultural pluralism in contemporary urban planning, the phenomenon of designing or maintaining distinctive spatial dominants is still noticeable. The church has always been the dominant in the perception of residents and it is also one of the most recognizable of the traditionally and historically established buildings. Today, these objects do not necessarily play the role of the tallest object in the space of a city or a housing estate, but they still play an important role as an element of spatial orientation, as a cultural and esthetic object.

The aim of this study is to determine the role played by contemporary parish churches built after 1945 in shaping the spatial structures of Szczecin’s housing estates and how these structures influence the social identity of residents. This study aims to formulate guidelines for the protection of young cultural heritage, treated as contemporary monuments. This study focuses on analyzing selected churches and architectural landmarks, defining their spatial types, their function in the context of the local environment, their composition, and their cultural significance for the community. This study focuses on analyzing contemporary religious complexes in relation to the principles of sustainable development and the protection of young cultural heritage.

In urban planning, a dominant is an object that stands out in the spatial structure of its surroundings in terms of its form, height, scale, or function. It may be a building, a tower, a monument, a square, or a natural form of elevation. The dominant not only organizes the space visually, but often acts as a symbol, becoming a point of reference in the mental topography of the inhabitants. In this context, the church combines several levels of meaning; it is a physical element with a form (tower, bell tower) distinguishing it from the surrounding objects, but also performs social and spiritual functions, and is sometimes a strong element of meaning for the local community. Compared to other types of landmarks such as skyscrapers, administrative buildings, and shopping malls, a church is distinguished by the durability of its functions and symbolism, although its significance is evolving, as we have witnessed in recent decades.

Activities developing directions for the preservation of young architectural heritage are the basis for sustainable preservation in the space of contemporary objects, because they are not only listed monuments, but they also constitute cultural heritage. The direction of this research is consistent with the pursuit of the 17 goals of sustainable development [

3], especially in the scope of the 4th goal of quality education, which speaks, among others, about access to universal and high-quality education, and the 11th goal of sustainable cities and communities. Linking sacred architecture with urban space means combining community spaces and co-responsibility for the environment. The Leipzig Charter is another document and argument confirming the legitimacy of research towards setting the framework for the protection of young heritage. This document indicates, among others, that the core of every sustainable urban development is culture, including its preservation and the development of heritage [

4]. The analyzed churches are a form of contemporary heritage. The development of the city should therefore be based on social justice; the protection of this heritage involves caring for the social integration nodes of the local community.

The UNESCO recommendation [

5] for the historical urban landscape extends the approach to the heritage of social value by treating the city as a dynamic multilayered cultural organism, which is particularly visible in the case of the churches and communities forming them.

The aim of this study is to identify and assess the role of parish churches, erected after 1945, in shaping the spatial structures of housing estates in Szczecin. The present study will help in the evaluation by identifying these objects as spatial dominant types, taking into account their function in the local environment, their composition, and their cultural significance for the community. Another important element is the assessment of the degree of spatial and formal integration of contemporary sacred units with the surrounding urban tissue, in relation to the principles of sustainable development and heritage protection. The elaboration of recommendations for the directions of the protection of young cultural heritage are referred to as for a contemporary monument.

The history of the formation of human settlements and the establishment of settlements shows that, in each period of our history, we will identify dominants important for the cultural heritage specific to a given era. The dominant element depicts the political and economic relations of the times in which it was created, while the church is additionally a spatial symbol. It should be noted that the urban development causes the natural disappearance of some historical objects, symbols that we used to know from the panoramas of cities. The authors of [

6] analyze the geometry, and the premises of the dominant’s existence rely, according to their research, on the principles of the urban design of the dominant in the contemporary interior. They analyze, among others, the urban interior; buildings with a leading visual impact, scale, and proportions; and how they affect the city space.

In the countries of increasingly secularizing Western Europe, a shift in the use of churches is progressing; they are transformed in museums, exhibition centres, and meeting centres, and this applies mainly to historic objects with a long history, often located in strict city centres. Such examples can be found, for example, in Lisbon, Siena, Lucca, and Brussels. In Poland, this is still difficult to imagine, but both in Poland and other parts of Europe it does not exclude the construction of new temples, which is the result of the ongoing development of human settlements. The adaptation of temples to their new function [

7,

8,

9] still arouses controversy and leaves the question of the boundaries of behaviour within the identity of architecture.

Twentieth-century modernist architecture sought to create “a new relationship between the interior and the exterior”. Its principles were open space, transparency, freedom of movement, the disintegration of mass, the disappearance of historicizing masks and symbols, and the collapse of hierarchical and dominant spatial effects [

10]. Both in our country and in Western Europe, the twentieth century saw the erection of many new churches. The difference between them resulted in many cases from the time of creation, esthetics, and cultural conditions, including, in particular, attachment to tradition [

11]. Among the many Polish churches, it is difficult to find minimalism and reductionism, which is particularly profound in Western countries. Excessively complicated forms prevail in our landscape [

12].

It should be noted that new churches in the structure of the modern city and settlements still play an important role; there are often spaces for meetings and integration for the local community. They constitute distinctive spaces, and they are distinguished places, facilitating identification through their difference in the shape of their forms and the cross, as the symbol that identifies them [

12]. The impact of places of worship on public space was discussed in article [

13], where the role of these places in shaping integration was emphasized, highlighting their contribution to the cultural heritage and identity of the city. It also emphasizes the importance of preserving the identity and esthetic values of places of worship among the processes of urbanization. The social importance of the church is strengthened by a sense of belonging and cohesion among the inhabitants thanks to cultural and religious events organized in the churches in question. These activities are addressed not only to nearby residents but to a wider group of residents of Szczecin. In this way, these churches have become important cultural objects that will also require protection in the cultural landscape of the city. These issues require further and expanded research on the identity of the urban landscape. It is important to set the direction of research on clarifying and creating a catalogue of such objects, determining their features, and identifying them as iconic in the urban landscape and also in relation to social assessments and preferences [

14,

15,

16].

In modern history, the location of new churches was not always associated with the selection of the most appropriate place. Both in the past and today, the stylistic, regional, and mental conditions that include the expectations of a given environment (especially the local community), for which the new symbol will become a clear dominant feature of, will constitute an important element [

17]. Places, where sacred objects are created, are always existential spaces, which, as the author states [

18], engage all the senses. In their work many of the architects drew on the achievements of Le Corbusier and his courage regarding the formal chapel in Ronchamp. There, light is one of the most important elements, shaping the interior of temples, and the symbolism of light is one of the richest in today’s culture [

18]. The sacral objects that have been selected for detailed analysis in relation to their role as a dominant feature in the urban space of housing estates simultaneously play a significant esthetic role. Their form is not only external symbolism but also a social function. The symbolism of light in the interiors of churches can be found in many buildings, e.g., in the churches of Corpus Christi, St. Dominic, and the Holy Cross, which are filled with mystical light that enriches the interior with variable colours of natural light rays, while demonstrating diversity in their bodies [

19], which particularly contributes to the architectural value of these objects.

The churches of Szczecin were also promoted by the city in the form of playing cards designed by architect Tomasz Sachanowicz. This architect placeed images of important cultural buildings on the cards, including three of the discussed churches [

20]. Iconic city buildings were the subject of research both in terms of promoting the image of the city [

21] and analyzing the strengthening the social cohesion of the urban landscape [

14].

Urban heritage is made up of many complex systems, landscapes, recognized monuments, modest buildings, and other structures. Each object has an external impact on the environment, which may be negative or positive, and at the same time it may also affect the understanding and assessment of neighbouring objects [

22]. Speaking of young heritage, the vast majority of objects in the urban environment still do not qualify for conservation activities in traditional heritage management, i.e., as monuments or well-defined conservation areas [

22].

2. Research Area and Data

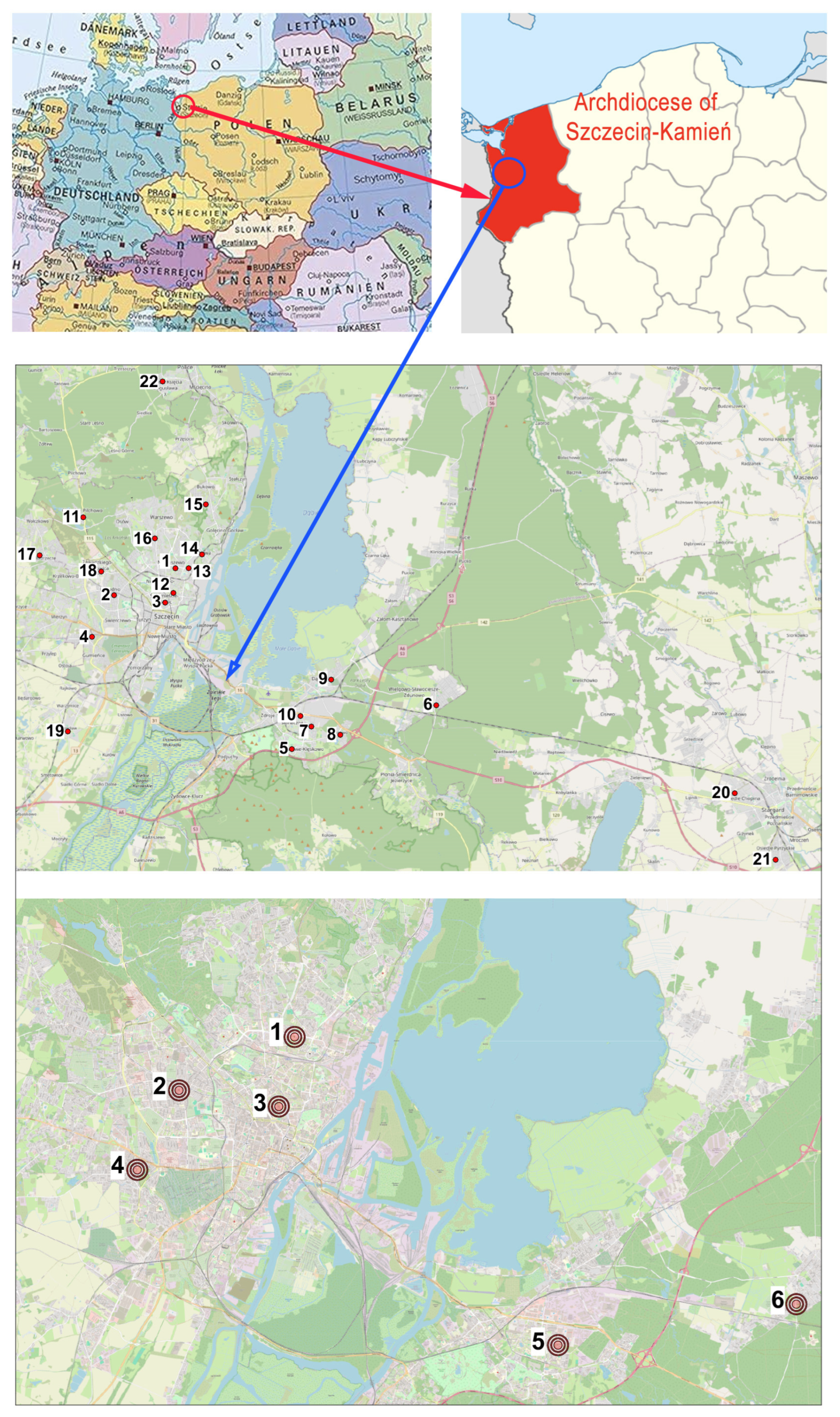

The place accepted for research is the Archdiocese of Szczecin and Kamień in the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, where the city of Szczecin and the surrounding area were selected. The objects accepted for research are Catholic parish churches built after World War II in the Archdiocese of Szczecin and Kamień. Szczecin is a city with a multilayered urban structure and a rich cultural heritage, shaped by historical changes, war damage, and intensive housing development during the second half of the 20th century. This area is a space with a complex cultural structure, in which the sacred architecture of the post-war period, i.e., following World War II, constitutes an important element of spatial and cultural identity, and for the immigrant, post-war population, it is a symbol of the urban and cultural heritage of its own area, created by itself.

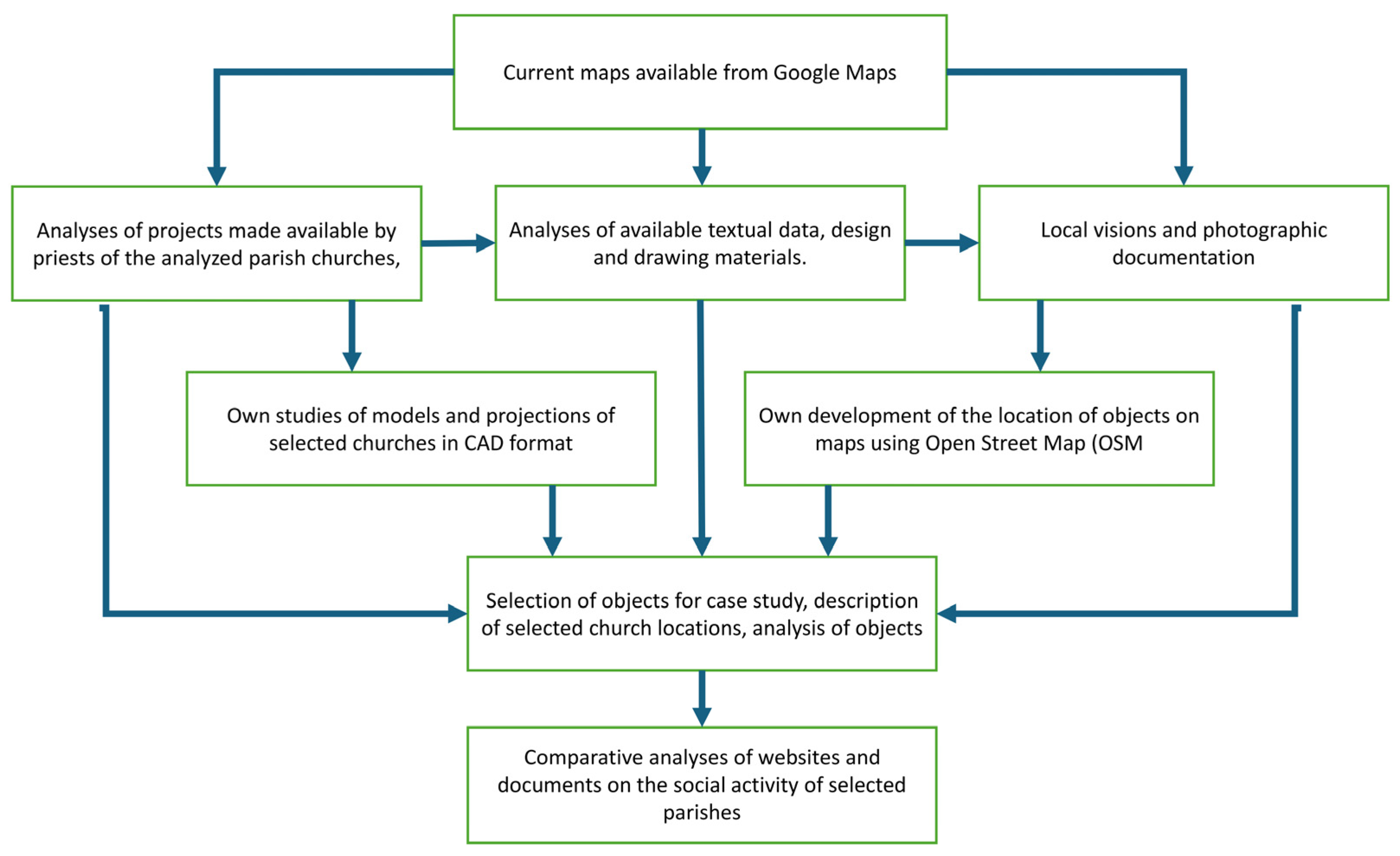

This research covered a wide collection of parish churches built after 1945. These objects were located on the areas of housing estates from different periods of the urban development of the city. New parish churches were located in the existing or developing spatial structure. As part of the first stage of research, we carried out a review and comparative analysis of twenty-two sacred objects located in various districts of Szczecin and its surroundings (

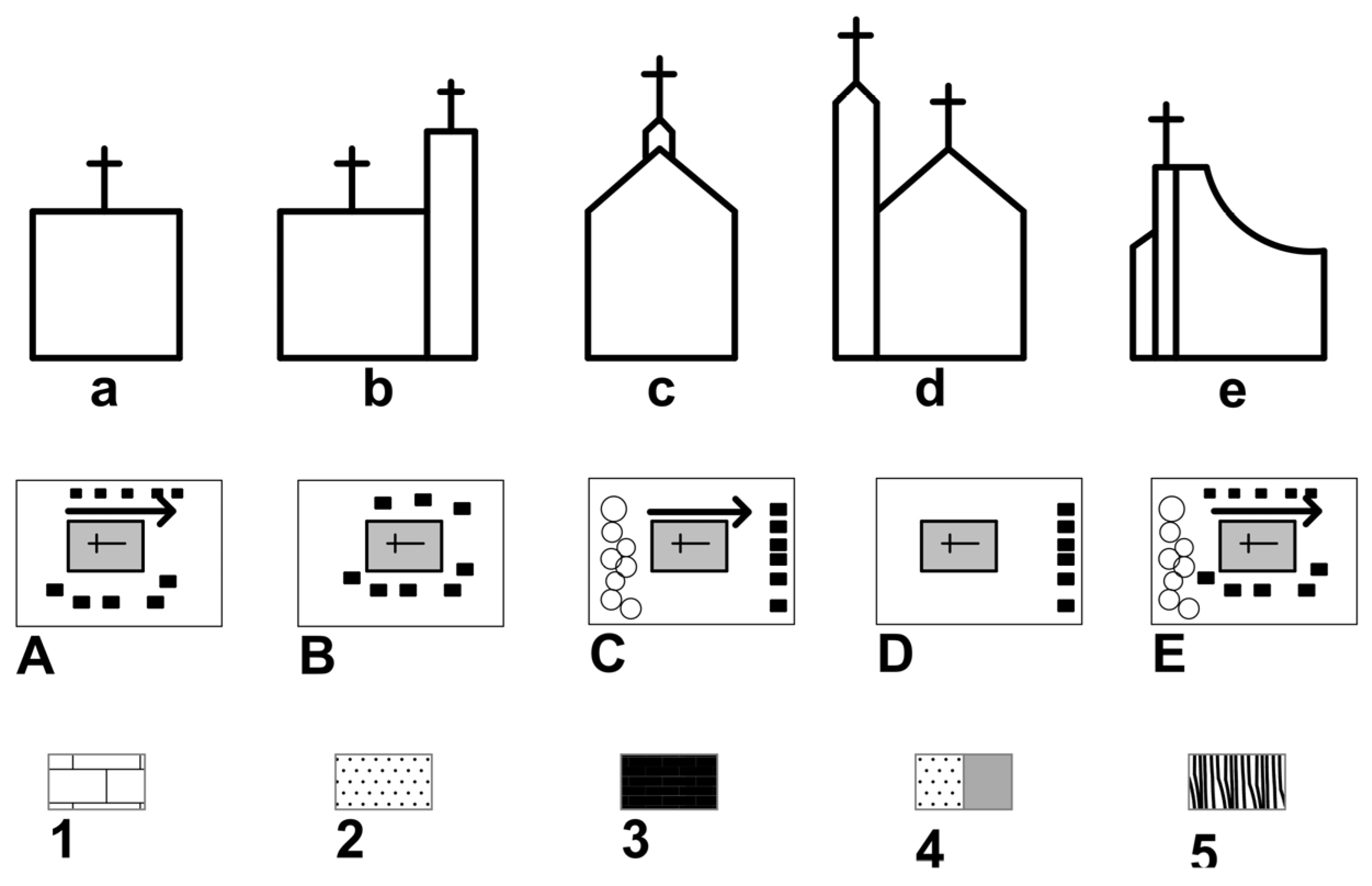

Figure 1). Schematic list of the most common architectural forms of churches, the types of surroundings and locations, and the type of finishing material used for the building included in the drawing (

Figure 2). The sacred objects selected for the initial study were collected in (

Table 1), which contains the basic points for the analysis, which were used for further division into research groups. Bearing in mind the preservation of sustainable cultural heritage and far-reaching thinking about the emerging young cultural area, these churches were classified into three typological groups. The resulting groups corresponded to different location strategies and spatial relations to the surrounding buildings:

The first group of objects are churches were created in a new urban tissue, in multi-family housing estates, as a parish created from scratch, and two churches of this group were selected for detailed research.

The second group of objects were churches created in the existing urban tissue among mixed single and multi-family mixed buildings, mostly pre-war, and supplemented by modern ones, and two churches of this group were selected for detailed research.

The third group of objects were churches created in a mixed space of newly created urban developments and existing pre-war buildings with a mixed intensity of buildings; two churches of this group were selected for detailed research.

For all these groups we performed detailed analysis of the location of the building, its visibility, type of architectonic form, the materials used for the facades, the socio-symbolic functions, and the environmental threats.

Table 1.

The sacred objects selected for the initial study in the area of the city of Szczecin and the surrounding areas. The table presents the initial points for the analysis for further division into research groups.

Table 1.

The sacred objects selected for the initial study in the area of the city of Szczecin and the surrounding areas. The table presents the initial points for the analysis for further division into research groups.

| No. | Location: The City of Szczecin and Selected Areas/Housing Estates/Churches | Estate Type | Location of the Church, Surroundings | Architectural Form | Dominant Facade Material |

|---|

| 1 | Szczecin-Niebuszewo of God’s Mercy | New blocks of flats | The centre of the housing estate, near the main artery; good exposure | Dynamic, sculptural body; visible bell tower | Two-colour sheet metal |

| 2 | Szczecin-Bukowe Kleskowo of Christ the Good Shepherd | New blocks of flats | The centre of the housing estate, off the main roads; good exposure | Historical form accentuated by the tower | Light clinker brick |

| 3 | Szczecin-Wielgowo of St. Michael the Archangel | Contemporary and pre-war detached houses | At the periphery of the housing estate, surrounded by greenery, near the main artery; good exposure | Modernist, simple, expressive body; dominant tower | Light plaster |

| 4 | Szczecin-Pogodno of the Holy Cross | Contemporary and pre-war single-family and mixed low-height buildings | The centre of the housing estate; poor exposure | Sculptural dynamic form, topped with a tower | Light plaster |

| 5 | Szczecin-Śródmieście of St. Dominic | New multi-family blocks/partially mixed contemporary and pre-war buildings | The centre of the housing estate, near the main artery; good exposure | Dynamic body accentuated by the vertical rhythm of the windows, with a signature | Dark clinker bricks |

| 6 | Szczecin-Gumieńce of the Transfiguration | Contemporary and pre-war single-family buildings | The centre of the housing estate, near the main artery; good exposure | Historicising form dominant tower | Colourful plaster |

| 7 | Szczecin-Majowe Divine Providence | New blocks of flats | The centre of the housing estate, off the main roads; good exposure | Simple form accentuated by the tower | Light plaster |

| 8 | Szczecin-Kijewo of St. Jadwiga of Poland | Multi-family and single-family housing from various decades | The centre of the housing estate, surrounded by greenery, near the main artery; good exposure | Historical form accentuated by the dome crowning the nave | Light plaster |

| 9 | Szczecin-Dąbie of the Visitation of Our Lady | Contemporary and pre-war detached houses | The centre of the housing estate, surrounded by greenery, near the main artery; good exposure | Expressive and dynamic form topped with a tower | Light plaster |

| 10 | Szczecin-Słoneczne of the Immaculate Heart | New blocks of flats | The centre of the housing estate, near the main artery; good exposure | Stylistically diverse sacral complex with very distinct tower | Dark clinker bricks |

| 11 | Szczecin-Głebokie St. Brother Albert Chmielowski | Contemporary and pre-war detached houses | The centre of the housing estate, close to greenery, near the main artery; good exposure | Expressive diversified body, further highlighted by the tower | Light plaster |

| 12 | Szczecin-Niebuszewo of Corpus Christi | New blocks of flats | Outside the housing estate among many service facilities, near the main artery; good exposure | A simple tent block with an unexposed bell tower | Light plaster |

| 13 | Szczecin

Żelechowa St. Nicholas | New blocks of flats | The centre of the housing estate, surrounded by greenery, near the main artery; good exposure | Historicising form accentuated by the tower | Dark clinker bricks |

| 14 | Szczecin

Żelechowa of St. Christopher | Contemporary and pre-war multi-family buildings | At the periphery of the housing estate, surrounded by greenery, near the main artery; good exposure | A simple body topped by a tower | Light plaster |

| 15 | Szczecin Bukowo of St. Faustyna Kowalska | Contemporary and pre-war single-family buildings | At the periphery of the housing estate, surrounded by greenery, near the main artery; good exposure | Historicising form accentuated by the tower | Dark clinker bricks |

| 16 | Szczecin-Warszewo of St. John Paul II | New multi-family houses; modern and pre-war detached houses | The centre of the housing estate, near the main artery; good exposure | Historicising form accentuated by the tower | Light clinker brick |

| 17 | Szczecin-Bezrzecze of Our Lady Mother of the Church | New single-family housing | Remote from the main road; poor exposure | Historicising form accentuated by the tower | Dark clinker bricks |

| 18 | Szczecin-Zawadzki of St. Otto | New blocks of flats | The centre of the housing estate, near the main artery; good exposure | Simple monumental body accentuated by a tower | Bright plaster |

| 19 | Szczecin-Przecław of the Visitation of Our Lady | Contemporary and pre-war dispersed single-family and mixed low-height buildings; new single-family, dispersed buildings | The centre of the housing estate, near the main artery; good exposure | Historicising form without a tower, with a signature | Light clinker brick |

| 20 | Stargard Christ the King of the Universe | Contemporary and pre-war single-family and contemporary multi-family buildings | Remote from the main road; poor exposure | Historicising form accentuated by the tower | Dark clinker bricks |

| 21 | Stargard of the Transfiguration | New blocks of flats | Remote from the main road; poor exposure | Historicising form accentuated by the tower | Dark clinker bricks |

| 22 | Police of St. Casimir | New blocks of flats | The centre of the housing estate, surrounded by greenery, near the main artery; good exposure | Historicising form without a tower, with a signature | Light clinker brick |

Figure 1.

The upper part of the map showing the locations of all analyzed objects in the city of Szczecin and the surrounding area. The lower part of the map shows the marked objects with the reference numerals 1–6, for those for which detailed analyses have been elaborated: 1—Szczecin-Niebuszewo of Divine Mercy, 2—Szczecin-Bukowe Kleskowo of Christ the Good Shepherd, 3—Szczecin-Wielgowo of St. Michael the Archangel 4—Szczecin-Pogodno of the Holy Cross, 5—Szczecin-Śródmieście of St. Dominic, 6—Szczecin-Gumieńce of the Transfiguration of the Lord. Source: Author.

Figure 1.

The upper part of the map showing the locations of all analyzed objects in the city of Szczecin and the surrounding area. The lower part of the map shows the marked objects with the reference numerals 1–6, for those for which detailed analyses have been elaborated: 1—Szczecin-Niebuszewo of Divine Mercy, 2—Szczecin-Bukowe Kleskowo of Christ the Good Shepherd, 3—Szczecin-Wielgowo of St. Michael the Archangel 4—Szczecin-Pogodno of the Holy Cross, 5—Szczecin-Śródmieście of St. Dominic, 6—Szczecin-Gumieńce of the Transfiguration of the Lord. Source: Author.

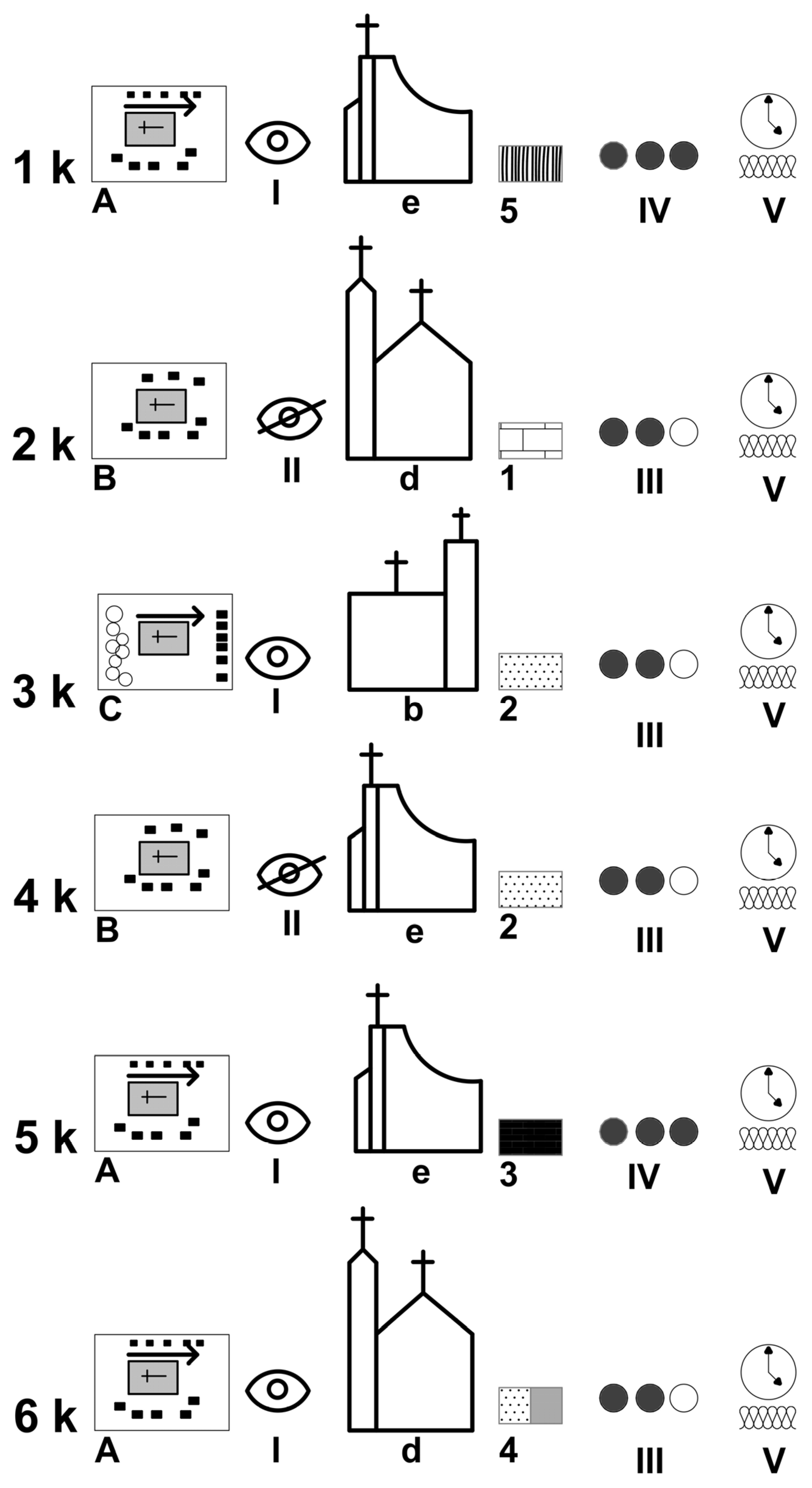

Figure 2.

Schematic list of the most common architectural forms of churches, the types of surroundings and locations, and the type of finishing material used for the building. Description of individual architectural forms: a—a simple monumental body without a tower, b—a simple monumental body accentuated by a tower, c—a historicising form without a tower, with a signature, d—a historicising form accentuated by a tower, e—a sculptural and dynamic form topped by a tower. Description of the locations: A—the centre of the housing estate near the main road, good exposure; B—the centre of the housing estate, poor exposure; C—at the periphery of the housing estate, surrounded by greenery, near the main road, good exposure; D—at the periphery, remote from the main road, poor exposure; E—the centre of the housing estate, surrounded by greenery, near the main road, good exposure. Dominant facade materials: 1—light clinker brick, 2—bright plaster, 3—dark clinker bricks, 4—colourful plaster, 5—other. Source: Author.

Figure 2.

Schematic list of the most common architectural forms of churches, the types of surroundings and locations, and the type of finishing material used for the building. Description of individual architectural forms: a—a simple monumental body without a tower, b—a simple monumental body accentuated by a tower, c—a historicising form without a tower, with a signature, d—a historicising form accentuated by a tower, e—a sculptural and dynamic form topped by a tower. Description of the locations: A—the centre of the housing estate near the main road, good exposure; B—the centre of the housing estate, poor exposure; C—at the periphery of the housing estate, surrounded by greenery, near the main road, good exposure; D—at the periphery, remote from the main road, poor exposure; E—the centre of the housing estate, surrounded by greenery, near the main road, good exposure. Dominant facade materials: 1—light clinker brick, 2—bright plaster, 3—dark clinker bricks, 4—colourful plaster, 5—other. Source: Author.

![Sustainability 17 06648 g002]()

4. Case Study—Description of Selected Church Locations

The three groups of churches accepted for this research are located within Szczecin and its surroundings; they are Roman Catholic parish churches built after World War II in the Archdiocese of Szczecin and Kamień in the West Pomeranian:

The first group:

The second group:

The third group:

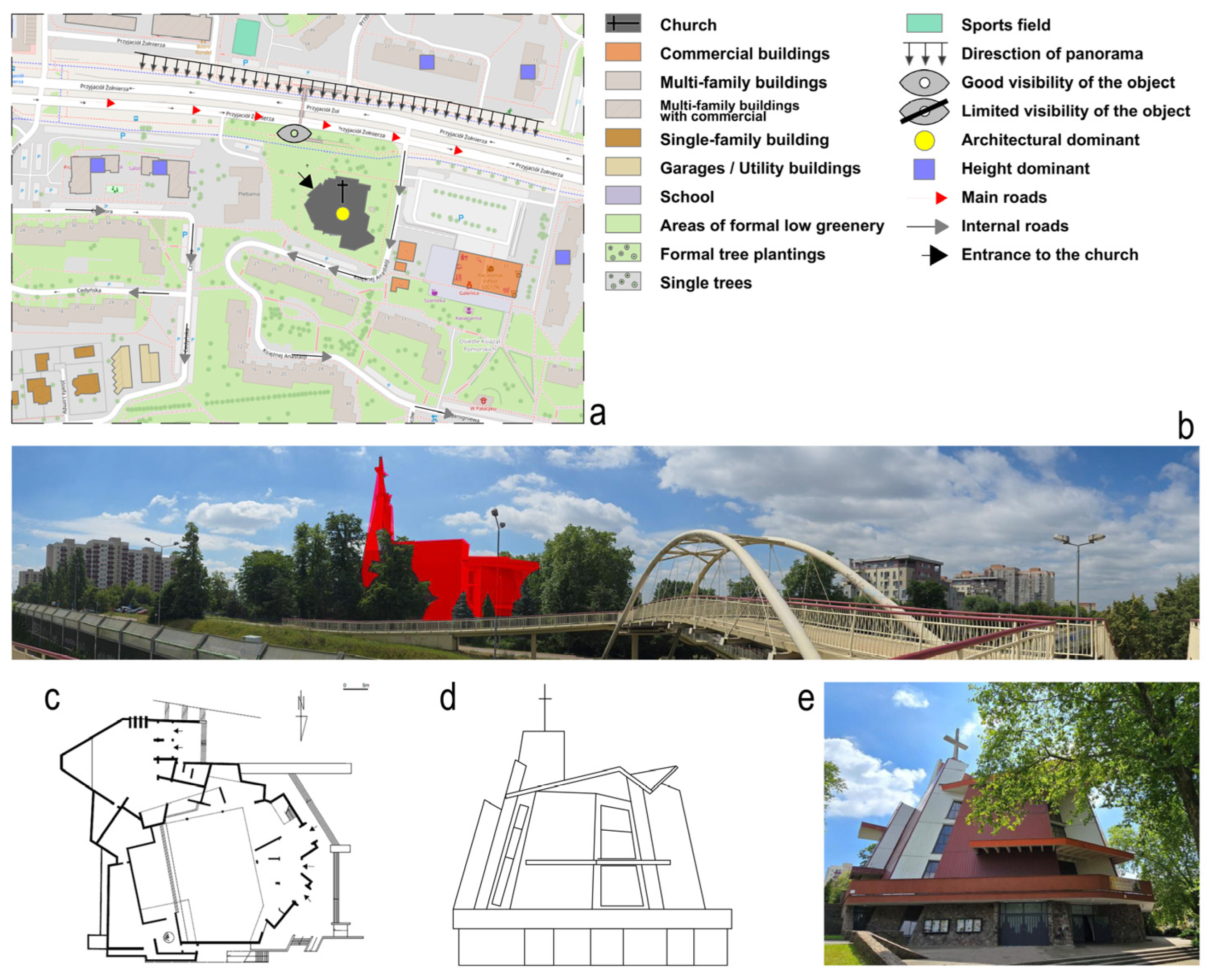

4.1. Parish Church of the God’s Mercy in Szczecin, Niebuszewo Housing Estate

The parish church was designed by A.M. Szymski. The object was built between 1980 and 1989, though its final appearance including the facade texture and colour was only apparent in the following years. The location of the object and its projection and view from the street as well as the 3D view are shown in (

Figure 4). The interior took on its final character after 2010. The object was built outside the strict centre on the edge of a newly built multi-family housing estate with a diverse development from four to ten floors. The silhouette of the object remained exposed and visible from both sides of the estate and from the main communication route of one of the largest road arteries in this part of the district. The body of the building combines two independent spaces, a church and a chapel, which complement each other. They are connected to each other at the ground floor, by means of an internal passage, allowing the faithful to freely use the selected sacrum zone during the services. Among these buildings, the church stands out not only with its symbol of the towering cross but also as a composition of forms with different wall planes which were designed by its architect. The designer envisaged the compositions of the temple as a mass of rock that burst and divided into many planes in relation to the bursting rock tomb. The adopted composition merges with the eastern part into the slope; in this way the effect of a solid growing out of it is also obtained. Expression and omnidirectionality are given to the body by its numerous horizontal canopies, planes united with diagonal walls. The building was built with use of reinforced concrete. The facade of the outer planes of the walls and the flat roof of the church are intersected by strips of vertical skylights, through which atmospheric light is passed into the interior. The spatial form of the object, with the irregular plane structure topped with a flat roof, is transversely separated by an upper longitudinal skylight, which constitutes the main natural light source in the temple. The church was not fully constructed according to plan, and its façade was not clad in stone. Due to a lack of funding, sheet metal and sections of plaster were added to the façade, completely changing the intended character of the building. A section of ramps for disabled people was built outside. These were intended to provide access to the choir, but were partially modified and left unfinished.

The silhouette of the temple is visible from the main road and the nearest spaces of the settlements. In the further vicinity of the church, the dominant features were created: a tall multi-family building, a complex of grocery stores, and a local market, while the existing nearby shopping centre from the end of the 20th century, built together with the housing estate, deteriorated significantly, thus offering a potential new location for another dominant with a service function in the vicinity of the church.

The analysis of available Internet sources [

24], parish website, announcements, and news demonstrates that there are fourteen groups and communities in the parish. These groups spur the social life of the residents of nearby settlements. There are numerous parish events held at the church, including fairs, days of selected patrons, retreat meetings, trips for parishioners, and all kinds of charity collections.

The analyzed object, due to the strength of its cultural significance for the local community, is fully recognizable in space. The massive size, and at the same time the sculptural diversity, makes this a centre-creating object, even though it does not dwarf the height of the surrounding buildings. This object can be considered a dominant in the space of the housing estate.

4.2. The Parish Church of the Good Shepherd in Szczecin, Bukowe-Klęskowo Housing Estate

The parish church was designed by A. Zaniewska. The object was built between 1998 and 2005. The location of the object and its projection and view from the street as well as the 3D view are shown in (

Figure 5). The construction was carried out within the newly emerging urban development for a multi-family housing estate in areas outside the strict centre of Szczecin in the right-bank district. The plan did not designate a place for the sacrum; it is located on the green area left in the general plan of the housing estate. The design of the church project by the co-architect of the estate made it possible to integrate its body with the space of the estate.

The object is located on an elongated flat plot between housing estates. It is located on a plot between pedestrian communication routes and the internal road from the south side. The area is not fully developed. The object is located with its front elevation towards the north, withdrawn into the plot, and thanks to the open space of the wide square in front of the temple, its facade is visible from the main communication route. The temple is not compositionally related to the objects surrounding it, as it is not a particularly high dominant within the housing estate, so it is difficult to locate it from a distant perspective outside the communication routes in its immediate vicinity. However, the church was designed in such a way that in the surrounding buildings, it became a recognizable object with a clear function. The architect used a form referring to the traditional basilica. The shape of the temple strongly refers to historical forms thanks to the elements used in the composition of the building body. This is an example of the contemporary research and interpretation of known forms that can be identified with the sacred function. The external walls of the building were covered with sand-coloured clinker brick, and the roof was finished with a dark brown tile. The colour scheme of the object strongly distinguishes it in the environment through two strongly contrasting colours—light and dark. An additional distinguishing feature of the facade colour scheme is the applied detail: the uniform beige clinker has been enriched with a number of materially homogeneous elements—windowsill, lintels, and pilasters. Among the monochromatic colours, the massive four separate entrance doors offer a strong accent. All these elements allow the church to be an accent among the surrounding buildings.

The silhouette of the temple is visible only in the space of the housing estate and its communication routes, as there are no significant functional features around the object; a large amount of greenery next to it boosts the presence of the object and connects it to a common space that is devoid of buildings, which clearly affects its orientation in space, creating a visible axiality with the greenery.

The analysis of available Internet sources [

25], the parish website, announcements, and news demonstrates that there are five active groups and communities in the parish. These groups spur the social life of the residents of the nearby settlements. There are numerous parish events held at the church, including retreat meetings, trips for parishioners, and all kinds of charity collections. The life of parishioners is centred around the church, which constitutes the central part of the urban layout of the housing estate. The analyzed building, due to the strength of its cultural significance for the local community, is fully recognizable in space. The massive, historicizing form is a centre-creating object, even though it does not dwarf the height of the surrounding buildings and despite the lack of exposure from the main streets. This object can be considered a dominant in the space of the housing estate.

The analysis of the objects of the second group covers two churches that were built in the existing urban tissue, incorporated into pre-war buildings, and their specificity, location, and time of creation are of particular importance for the maintenance of the sustainable cultural heritage of the studied area.

Both buildings are located in a space where most residential buildings are listed in the municipal register of historic monuments.

4.3. Parish Church of St. Michael the Archangel in Szczecin-Wielgowo

The parish church was designed by T. Szuta. The location of the object and its projection and view from the street as well as the 3D view are shown in (

Figure 6). The object was built between 1976 and 1977. The church was built in part of a largely pre-war housing estate of single-family houses near Szczecin. The object is located on the main road at the end of the housing development existing on its side. The plot itself is located in the vicinity of the forest buffer zone; the church is located on an extensive plot in its corner part at the main street near the greenery. Originally, in the place of the present church, there was a residential building adapted for the purposes of worship. Its technical condition prevented further use, so as a result, a new object was built. The temple is laid out on an oblong plan with a separate rectangular chancel, illuminated by side glazing and a lunette directed towards the altar located centrally above the chancel. The openwork bell tower was located on the right side of the building and connected to the nave. The side nave was separated from the church and covered with a separate flat roof—inside it there is a sacristy and a chapel. The entrance is oriented axially to the altar and the layout of the temple body is symmetric.

The building was erected using a skeleton frame. In the facade, the structure was externalized, emphasizing the vertical arrangement of the columns in grey. Above the nave and the presbytery, a box flat roof was used. The facade of the church has an accented entrance, emphasized by a tower with the signature of the cross. The form of the object is a simple: it is a modernist body with an exposed structural layout. The church originally featured a distinctive detail on its facade, with concrete slabs adorned with concave circle and cross symbols forming a monochromatic mosaic. This mosaic has since been entirely removed and replaced with light-coloured thermal insulation.

The silhouette of the temple is visible from the main communication route, and there are no significant functional features around the object; a large amount of greenery next to it boosts the presence of the object and connects it to a common space that is devoid of buildings, which clearly affects its orientation in space. From all sides of the road, the body of the church is clearly visible because in space it is also dominant in terms of its altitude. The lack of direct development does not exclude the possibility of a change in the way the space is used.

The analysis of available Internet sources [

26], the parish website, announcements, and news demonstrates that there are ten active groups and communities in the parish. These groups spur the social life of the residents of the nearby settlements. There are numerous parish events held at the church, including retreat meetings, pilgrimages for the faithful, and all kinds of charity collections. The analyzed object, due to the strength of its cultural significance for the local community, is fully recognizable in space. The simple form of the object, further clearly emphasized by vertical stripes and the church tower, stands out from the space and is an architecturally strong accent on the housing estate of single-family houses. This object can be considered dominant in the space of the housing estate.

4.4. Parish Church of the Holy Cross in Szczecin Pogodno

Parish church designed by Z. Abrahamowicz. The object was built between 1972 and 1978 (

Figure 7). The church was built in the central part of the existing villa complex of pre-war residential buildings, mainly comprising detached houses and later supplemented with multi-family houses. The building was built as a new church, partly incorporating the existing pre-war church. It is the first church to be expanded after the Second World War. It is located on a very small plot between the numerous residential buildings surrounding it. It was designed and planned to have a circle section, which ends with a semicircular presbytery, the wall of which consists of regularly arranged columns with stained-glass panels. The nave was designed in an amphitheatre arrangement with a centrally located altar. The main entrance to the temple is located on the south side with an indirect orientation to the altar. The building was erected using reinforced concrete. The end of the body on the south-eastern side creates a high monumental church tower. The tower is designed in the form of a wing with a bell placed in its cut interior, and the visible horizontal indentation in the form of a shelf forms the sign of the cross—this symbol of the temple emerges from the tight surroundings of the housing estate amidst which it was built. The church was changed inside; the original simple character of its interior plasticity was disturbed, though Renaissance balusters were left at the altar.

The silhouette of the temple is visible from the main communication route; there are no significant functional features around the object. The dense buildings around the church which are of quite similar forms with an ordered height do not compete with the church. The tower with its cross rises above the surrounding buildings, making it a landmark in the area of the estate. The building body of the church does not have good exposure; the tight construction around it and the lack of a large square and departure from the body do not allow for the exhibition of the form in all its glory. The expressive shape and diversity of form make this church a dominant, not only in a functional sense. The dense development around the church does not give the possibility of further functional changes in the area in the future, which could further isolate the functional dominant.

The analysis of available Internet sources [

27], the parish website, announcements, and news demonstrates that there are eleven active groups and communities in the parish. The adjacent rectory is home for nuns, who live and work for the benefit of the residents. Parish groups spur the social life of the residents of the Pogodno district. There are numerous parish events held at the church, including retreat meetings, trips and pilgrimages for parishioners, and all kinds of charity collections. In cooperation with nuns, classes for children and adolescents are also conducted. The life of parishioners is centred around the church, which is the only centre-creating object of this housing estate. The analyzed object, due to the strength of its cultural significance for the local community, is fully recognizable in space. Its expressive shape, diversity of form, and elevation, and also the tower of the church, clearly emphasized by the vertical layout of the columns, stand out from the space; it is an architecturally strong accent within the discussed housing estate. This object can be considered a dominant in the space of the housing estate.

An analysis of the objects of the third group is presented for two churches built in the vicinity of new multi-family blocks and partly comprising mixed contemporary and pre-war buildings, and their specificity, location, and time of creation are of particular importance for the maintenance of the sustainable cultural heritage of the studied area.

Both buildings are located in a space where residential buildings are located in the vicinity: for the first church—tenement houses listed in the municipal register of monuments, and for the second one—prewar single-family buildings with large urban planning values. The first church of St. Dominic was built in the district of Szczecin-Śródmieście and the second of Transfiguration was built in the district of Szczecin-Gumieńce.

4.5. Parish Church of St. Dominic in Szczecin Śródmieście

The parish church was designed by W. Zaborowski. The object was built between 1996 and 2000 (

Figure 8). This church with a monastery was constructed in the city centre in the existing urban tissue among multi-family post-war buildings and multi-family pre-war tenement buildings with a high intensity of development. The object is located in the city centre, surrounded by many functional landmarks, a complex of schools and public institutions, the Pleciuga Theatre, and high-rise buildings. It is located at one of the main streets on a corner plot to the north, adjacent to a school playground and a parking lot. The church together with the internal chapel, the pastoral and parish part, and the monastery form a sacred ensemble, which forms a compact, interconnected object. There is a church square at the main entrance to the temple. In the depths, the area has a diverse shape and has been developed with greenery. The body of the church building is located on a side elevation parallel to the pedestrian route, with an entrance from the west. The church body does not dominate the surrounding buildings, nor does it dominate with its scale; the monastery part is adjusted in height to the surrounding buildings. The church stands out in the surrounding space with the material and form used. The main body of the church, as seen from a bird‘s-eye perspective, stands out from its surroundings in a clear way, thanks to the distinctive elements of the carved roof form, clearly emphasizing its dominance. However, the main body of the church, as seen from a bird‘s-eye perspective in a clear way, thanks to the distinctive elements of the carved roof form, clearly emphasizes its dominance. The church was built on a square projection, the diagonal of which marks the dedicated zone in the eastern corner—the altar. Multi-planar, zigzag-shaped walls have corner bends with glazing. These illuminate the interior and enclose the body in a square arranged diagonally. The church plays the role of a multifunctional facility, where the main body with a central projection is the church, and the monastic parts continue to blend into this solid structure.

The silhouette of the temple is visible from the main communication route. There are many significant functional features around the object: a high-altitude object was also built in the 21st century, and objects with public utility functions are also being expanded. The dense multi-family buildings surrounding the church are of quite similar forms, but of variable height, so the church does not dominate in height here. A free-standing tower that would stand out above the church was designed, but never constructed. The church has good exposure and the whole building body is visible from the frontage of the road. A strong shape with a different form in the environment, a durable finishing material, and strong vertical accents shaping the windows make this church a dominant not only in the functional sense. The church focuses on additional functions that strongly mark its presence in the city. The dense development around the church does not give room for further functional dominants in the future.

The analysis of available Internet sources [

28], the parish website, announcements published therein, and news demonstrates that there are fourteen active groups and communities in the parish. The church is adjacent to the monastery of the Dominicans, who actively cooperate in groups and communities with the inhabitants of the parish. Parish groups spur the social life of the residents not only in the city centre, but also many other residents of Szczecin, especially youth and academic groups. There are numerous parish events and cyclical fairs held at the church. There is a theatre group and there are also retreat meetings, trips, and pilgrimages for parishioners. All kinds of charity collections are organized. The life of parishioners is centred around the church, which is a centre-creating object for this midtown district. The analyzed object, due to the strength of its cultural significance for the local community, is fully recognizable in space. Strong and emphasized by its colour and material, the shape and diversity of its form and the clearly emphasized vertical lines of the windows stand out from the surrounding buildings. The church is an architecturally strong accent in the discussed housing estate and in part of the Śródmieście district. This object can be considered dominant in the space of the housing estate; it is a church of great and strong social importance.

4.6. Parish Church of the Transfiguration in Szczecin Gumieńce

The parish church was designed by W. Zaborowski. The object was built between 1993 and 1996 (

Figure 9). The church is located in one of the districts of Szczecin, near the structures of newly built multi-family buildings with a low development intensity and amidst some pre-war single-family houses. The church is located on a large corner plot with a varied shape. The area at the entrance to the church is flat, with a large open paved square, a bypass, and well-groomed greenery. On the plot next to the church there is a parish house. The sacral building is directly adjacent to multi-family three-storey buildings, and it constitutes a spatial dominant in its surroundings by means of its form and size. Around the church there are also functional dominants: schools. The design was adapted to the needs of the local parish and is a modified form of the church from Police. The church has a single function only, and it is built on a Latin cross plan with a single nave with a transept with an oblong plan, and a separate presbytery and a choir in the entrance zone above the porch. The church has a tower attached to the body of the building, and its simple form strengthens the object, giving it a dynamic appearance and strongly affecting the surroundings. The current form of the tower differs from the original design. In the main façade, the wall is divided into five parts: In the middle there is the main entrance, while the side entrances retreat towards the centre. Two side vertical strips of windows accentuate the entrance, which is clearly visible from the street frontage. The external walls of the church facade are painted beige. The main body is a closed design, but the added sacristy is cut off from the form, disrupting the compositional whole.

The silhouette of the temple is visible from the main communication route; there are also functional dominants around the object. The varied multi-family and single-family buildings surrounding the church are of relatively similar forms, but of variable height, so the church dominates in terms of height here, and also with its dynamically shaped tower. The church has a good exposure and its whole body is visible from the frontage of the road and from the surrounding housing estates. The form of the church stands out in the surroundings; it has strong vertical accents, a large square in front of the church emphasizes its shape, and the church in this space of the estate is a dominant not only in terms of function. The church focuses on additional functions that strongly mark its presence in a part of the estate. The buildings around the church do not give room for further functional dominants in the future.

The analysis of available Internet sources [

29], the parish website, announcements published therein, and news demonstrates that there are twelve active groups and communities in the parish. These groups spur the social life of the residents of nearby settlements and the Gumieńce district. There are numerous parish events held at the church, including retreat meetings, trips, pilgrimages for the faithful, and all kinds of charity collections. The analyzed object, due to the strength of its cultural significance for the local community, is fully recognizable in space. It has a strong and vertically accentuated building body, the form of the tower dominates it, and the clearly marked location in the frontage makes it possible to distinguish the church from the surroundings. The church is an architecturally strong accent in the discussed housing estate. This object can be considered dominant in the space of the housing estate; it is a church of great social importance.

6. Discussion

Numerous authors have analyzed sacral architecture in the areas of new housing estates, noting that the analyzed buildings stand out from the environment with their architectural forms. These objects are important for most members of the local community, and their function creates clear places in the urban tissue that are conducive to the integration of parish communities [

32].

The author of the book

Betonowe Dziedzictwo [

33] devotes one of the chapters to contemporary churches built in the times of the Polish People’s Republic and describes the architectural values of these objects. These churches, as he notes, are of peculiar value; their material form can also be a reference to their symbolism and there is a clear difference in the space in which they existed, which often makes them a dominant feature of this space and a form of cultural heritage. On the other hand, in the book

Opowieści Budynków [

34], the author deals with the problems of architecture, including its general issues, and issues of esthetics and spatial layout. He also pays attention to new churches in Poland. Many researchers analyze the development and role of the contemporary church in the urban space, both in the context of Poland and Europe. The intensive development of cities and the shifting of their borders impose the need for the planning and construction of new settlements, often accompanied by the absorption of the existing urban tissue. Observations of contemporary sacred buildings against the background of historical and cultural conditions are further discussed by J. Rabiej [

35], who is also the designer of several sacred objects constructed in suburban spaces.

All important architectural issues of the contemporary churches in Krakow created until 1989 [

36] were traced by J. Sz. Wroński as a process of the change taking place in the construction of churches. This reference broadens the knowledge and gives a comparison of the studied area and the churches selected for analysis.

The cited authors do not suggest that these objects should be protected, nor do they classify them as a young heritage, although they do notice their roles and importance in space. Of course, not all new objects created after the war are of significant architectural value. They are rather symbols that should also be taken care of.

The erection of temples in the time of the Polish People’s Republic was a sign of both faith and protest against the atheistic state. The churches built not only became a place of worship, but they also became a symbol, a landmark in space for the local community [

37]. Referring to these theorems, we can also observe their confirmation in the case of the analyzed objects, as listed in the table (

Table 2,

Figure 10).

In the light of the analyses of six selected parish churches in Szczecin, their important role in shaping the structures of housing estates becomes apparent. These objects are churches, varied in their composition and style, and they constitute permanent points of reference in the spatial and cultural system. The results of the analyses prove that the post-war churches permanently inscribed in the cultural landscape of the city are identified as spatial reference points, and can be further defined as a living heritage. This approach is in line with the assumptions of the UNESCO Recommendation of 2011 [

3], which extends the definitions of heritage to contemporary objects of significant social and landscape importance. These churches can be seen as integral elements of the historical urban landscape, even though they were built in the second half of the 20th century. They also fit into the concept of contemporary heritage according to the New Leipzig Charter, which emphasizes the directions of action towards their inclusion in the urban policy of the city [

4]. Parish churches can constitute social nodes, strengthen local identity, and foster further integration. This is in line with the implementation of Objective 11 of the UN 2030 Agenda, which assumes the creation of sustainable, safe, and inclusive cities [

5].

The contemporary heritage of the architecture that surrounds us and creates dominants around us, which are symbols of our identity in place and time which exist before our eyes, becomes a contemporary monument; the problem and the scope of its protection is currently the most important issue for the future. Ongoing discussions in the architectural and academic environments are directed towards the development of regulations for the protection of post-war architecture and the most valuable newer buildings. This process has been discussed in many countries [

38]. We must be aware that among these objects there are also churches, which are architectural manifestations created in search of the dominant form in space; however, their form of protection may constitute a much greater scope of research and regulation. Numerous researchers have voiced their opinions on the implementation directions for heritage protection [

39,

40], at the same time stressing the opportunities that the contemporary researchers have in form of modern tools and digital technologies for the protection, valorisation, and use of cultural heritage. The cultural heritage and its significance for communities can be enhanced by the application of digital tools to enrich the strategies based on the promotion of city culture [

39].

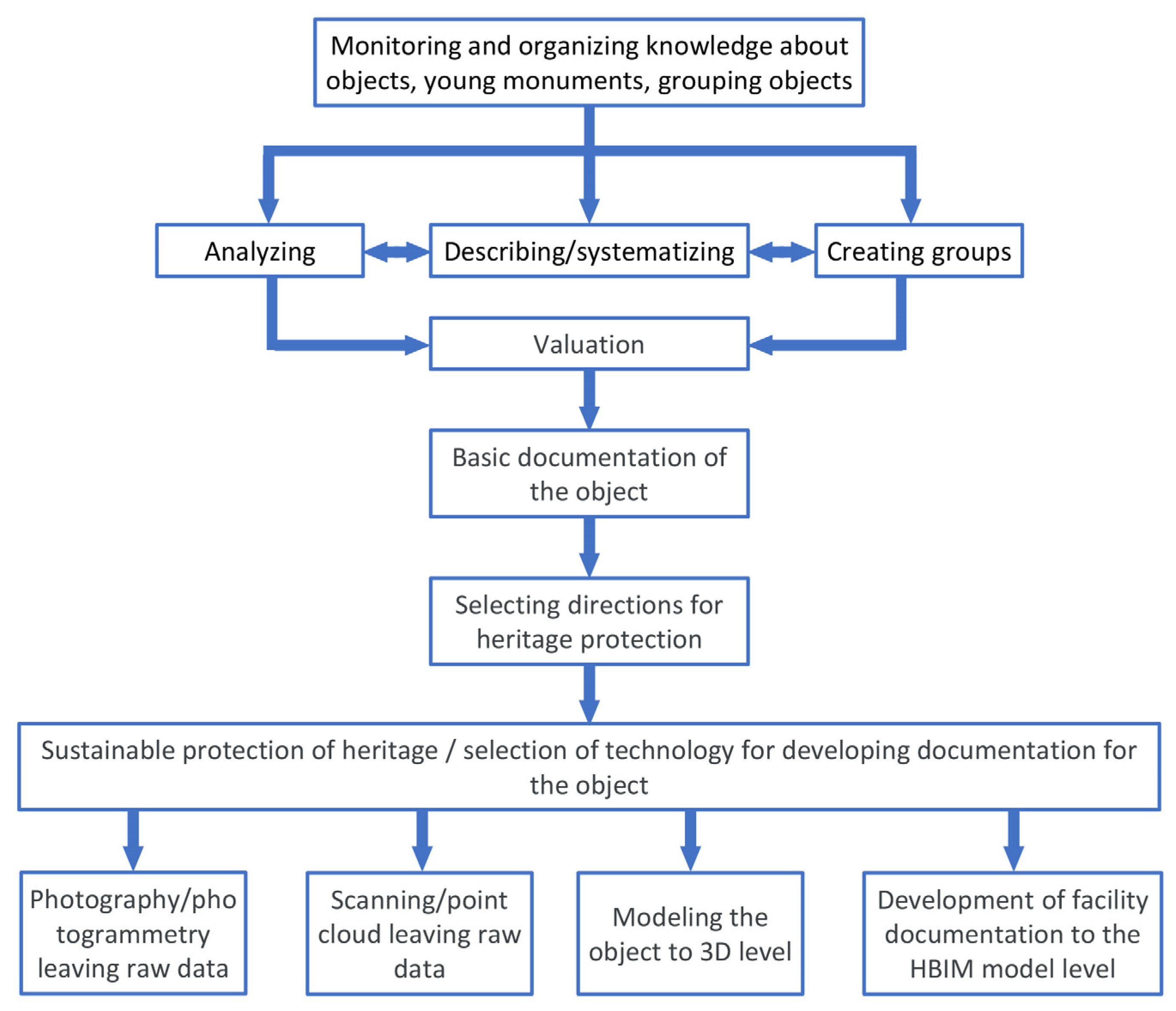

The discussion about their place in the city structure in relation to the church of the Holy Cross in the Szczecin-Pogodno district and the church of St. Michael the Archangel in Szczecin-Wielgowo indicates the need to treat them as a young cultural heritage that requires recognition and protection strategies. Although these churches were created in various political conditions, they nevertheless constitute important spatial and environmental dominants. In the context of sustainable urban development, it should be emphasized that sacred complexes, even without the formal status of a monument, should be analyzed as heritage elements in need of protection. Some of such objects, especially in peripheral layouts or post-war settlements, act as strong spatial and social accents, despite their lack of a monumental scale. This indicates the need to develop new tools for the evaluation and classification of the cultural value of objects created in the 20th century. This year’s European Heritage Days events are focused on architecture and young heritage, which may be a good direction for changes in the way contemporary urban and cultural heritage is protected. The care for the sustainable protection of urban and cultural heritage requires an interdisciplinary approach, and it should start with the valorisation of resources, preparation of a conservation strategy, drafting of a plan for preserving young heritage, and popularization of knowledge about architecture. The direction of further research is to develop the specific stages to be taken towards the preservation of young heritage (

Figure 11).

7. Conclusions

The conducted spatial and urban analysis demonstrated that modern churches, despite changing architectural trends, still play an important role as a dominant feature in the structure of housing estates. Their function is not only limited to the sacred role—they also perform important indicative, compositional, and social functions. Despite the diversity of architectural forms, scales, and finishing materials, most of the analyzed temples have clear stylistic features and characteristic building bodies that distinguish them in the local urban context in which they constitute urban and cultural heritage. Churches are often located at the main communication routes in spatially and symbolically central points, where they strengthen the layout of the housing estate as a clear spatial system. Their presence organizes the urban tissue, gives it a meaningful character, and can perform the function of integrating the local community. At the same time, there are differences between sacred forms designed during the construction boom of the 1980s and 1990s and modern solutions referring to the esthetics of minimalism and the conscious exposure of the building body. In the face of the progressive urbanization and fragmentation of urban space, the church can still act as a permanent sign of identity and reference—both in a spatial and cultural sense.

The visibility and visual significance of the reception are shaped not only by the height, but by the exposure, the body shape, the architectural detail, and the colour scheme. Contemporary temples often adopt an extensive social function, providing a place of integration, meetings, and support—which is confirmed by field observations and analysis of the functions of sacred ensembles. As a compositional element, the church organizes local space not only formally, but also functionally.

Research has shown that contemporary churches, despite their changing urban context, continue to serve as architectural landmarks in urban spaces. These churches have a significant impact on shaping social identity and integrating local communities. Analyses have shown that these churches, despite the lack of formal protection, possess the characteristics of young cultural heritage. These buildings, with their distinctive, expressive forms and dominant spatial significance, require consideration in the protection of young cultural heritage.

The sacral significance of the building is combined with its strong social function—integrating residents through parish and neighbourhood events. The designed forms of objects and the types of space devoted to them acquire certain codified meanings. We create a space with the help of interior objects, shaping its specific forms, which have both functions and meanings, especially for its users. The space which we build not only has a material dimension, but also a symbolic one, because it is marked by emotions, feelings, and values [

41]. Preserving all these values is possible if the following strategic actions are adopted:

Determining the meaning and identification of the object;

Recognising the social function and valuation of architectural forms, even though they do not have the status of a historic monument;

Developing a local strategy for the protection of such buildings in the spirit of sustainable development;

Creating an urban register of young heritage.