Abstract

The transition to hybrid work has become a defining feature of the post-pandemic IT sector, yet organizations lack empirical benchmarks for balancing flexibility with performance and well-being. This study addresses this gap by identifying an optimal hybrid work structure and exposing systematic perception gaps between employees and managers. Grounded in Self-Determination Theory and the Job Demands–Resources model, our research analyses survey data from 1003 employees and 252 managers across 46 countries. The findings identify a hybrid “sweet spot” of 6–10 office days per month. Employees in this window report significantly higher perceived efficiency (Odds Ratio (OR) ≈ 2.12) and marginally lower office-related stress. Critically, the study uncovers a significant perception gap: contrary to the initial hypothesis, managers are nearly twice as likely as employees to rate hybrid work as most efficient (OR ≈ 1.95) and consistently evaluate remote-work resources more favourably (OR ≈ 2.64). This “supervisor-optimism bias” suggests a disconnect between policy design and frontline experience. The study concludes that while a light-to-moderate hybrid model offers clear benefits, organizations must actively address this perceptual divide and remedy resource shortages to realize the potential of hybrid work fully. This research provides data-driven guidelines for creating sustainable, high-performance work environments in the IT sector.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Statement and Its Significance

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought unprecedented changes to organizations’ operations, accelerating the transition to remote work and hybrid work models [1]. The IT sector, known for its digital orientation and agility, quickly adapted to the new circumstances, adopting new forms of work that brought numerous positive effects: increased flexibility, better work–life balance, time and cost savings, enhanced productivity, and access to a broader talent pool [2]. Post-pandemic, most knowledge-intensive firms have migrated to hybrid work, i.e., an intentional mix of remote and office days designed to combine flexibility with on-site collaboration.

The abrupt pandemic-era pivot to working from home turned the IT sector into a natural laboratory for location-flexible work. The COVID-19 pandemic triggered an unprecedented, global experiment in remote work, defined as performing paid tasks exclusively away from the employer’s premises using information-and-communication technologies (ICT). What began as an emergency solution has settled into three recognizable work modalities, defined by the authors of this paper as

- Remote—All tasks are performed away from the employer’s premises (0 office days in a standard 21–22-day month).

- Office-based—Staff work on-site virtually almost every day (≥16 office days; ≈≥80% attendance).

- Hybrid—Any mix between those extremes (1–15 office days)

Early evidence highlighted the upside of remote work—greater autonomy, broader talent pools, fewer commutes—but also underscored downsides: social isolation, coordination delays, unequal resource access, and ambiguous boundaries between work and home. As IT companies reopen offices, leaders still lack an empirical rule-of-thumb for how many office days preserve flexibility without eroding collaboration or well-being and potentially impacting various aspects of employee quality of life and work, such as job satisfaction and stress levels. However, the transition to remote work also brought challenges such as social isolation, burnout syndrome, resource access inequality, and difficulties in maintaining an organizational culture [3]. Additionally, the blurring of boundaries between work and private life and increased workload can lead to chronic stress, negatively affecting employees’ physical and mental health [4].

In the IT sector—the vanguard of digital adoption—leaders now ask a deceptively simple question: how many office days are enough? Too many days may erode employees’ autonomy and increase commuting stress; too few may weaken team cohesion and managerial oversight. The research presented in this paper aims to resolve this dilemma by exploring the perspectives of employees and their managers in the IT sector in order to find an optimal balance for everyone. It is important to note that the term “optimal” in this research reflects the respondents’ personal preference, or what they perceive as most suitable or convenient for them, based on their individual experiences and priorities.

To address this central question, our study operationalizes and examines three critical constructs: perceived efficiency, perceived stress, and adequacy of remote-work resources. Perceived efficiency is defined not by objective output metrics, but by the employees’ subjective assessment of when they “faster and better complete work tasks”. This aligns with Self-Determination Theory (SDT), which suggests that the autonomy afforded by hybrid work can enhance intrinsic motivation and, consequently, self-rated performance. Perceived stress is conceptualized as a comparative burden, captured by asking employees which work modality they experience as more stressful. From a Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) perspective, this variable weighs job demands, such as commuting and office-based pressures, against resources, including flexibility. Finally, remote-work resource adequacy measures the perceived level of company-provided support for working from home, ranging from “very inadequate” to “fully adequate”. This construct is a cornerstone of the JD-R model, as organizational resources are critical buffers against potential job demands, directly impacting both stress and efficiency.

Beyond identifying an optimal work model for employees, this research addresses a second, equally critical, objective: to uncover and quantify the perceptual gap between employees and managers. While the benefits and drawbacks of hybrid work are often debated, less is known about whether those who design work policies (managers) and those who experience them daily (employees) see the model through the same lens. A misalignment between their perspectives on key issues—such as the efficiency of hybrid work and the adequacy of provided resources—can lead to ineffective policies, employee disengagement, and wasted resources. By systematically comparing the responses of these two groups, our study aims to expose this potential disconnect, providing a more complete and actionable picture for organizational leaders.

The results of this research hold significant importance for several stakeholders. For IT companies, the findings provide empirical evidence to inform strategic decisions regarding work modality policies, helping these companies to optimize operational efficiency and create sustainable work environments resilient to future disruptions. Managers can gain insights into the differing perspectives of employees and the factors influencing employees’ stress and work efficiency in remote and hybrid settings, enabling more effective leadership.

By (i) quantifying an empirically “safe” hybrid window and (ii) exposing employee–manager perception gaps, the study offers actionable guidance to IT leaders crafting post-pandemic work policies.

1.2. Remote and Hybrid Work: State of the Literature and Research Gap

1.2.1. Evolution of Research Pre- and Post-COVID-19

Although a significant body of research on remote and hybrid work exists, most studies focus on the period during the COVID-19 pandemic [5] and immediately after it [6], while relatively few have examined remote-work practices before the pandemic [7]. Before 2020, the empirical evidence on telework was modest but generally optimistic: voluntary, part-time work-from-home arrangements were linked to higher job satisfaction, minor productivity gains, and reduced turnover [8]. The COVID-19 lockdowns then triggered an unprecedented natural experiment in mass remote work, producing a great research environment. For example, we have more than 2000 Scopus-indexed papers that explored forced, full-time remote work across sectors [9]. Meta-reviews show that outcomes during this period became highly contingent on context: some studies report productivity gains of up to 13% and others around a 10% decline, depending on factors like job type, home office setup, and managerial support [10,11]. Well-being findings were equally mixed: while flexibility reduced commuting stress, in contrast, social isolation, “technostress”, and blurred work–life boundaries elevated burnout risk [12,13]. Notably, there has been little research into the long-term effects and optimal work models in the post-pandemic period, especially in the context of the IT sector [14].

1.2.2. Key Themes Emerging from Recent Studies

On one hand, remote work offers numerous benefits such as increased productivity and greater flexibility [15,16]. On the other hand, potential downsides have been noted, including feelings of isolation [7] and communication challenges among dispersed teams [17]. Major themes from the recent wave of studies include the following:

- Productivity and performance. Overall, hybrid schedules of two to three remote days per week often maintain or slightly improve employee output [18]. In some cases, even full-time work-from-home has yielded significant productivity gains [19]. However, fully remote arrangements can hamper informal learning, spontaneous communication, and innovation if not managed well [17,20].

- Employee well-being. Autonomy and reduced commuting generally enhance life satisfaction and can improve work–life balance [21,22]. These benefits materialize only when organizations provide clear boundaries and adequate ICT support to remote workers [21]. A lack of boundary management can lead to work–family conflict [23] and elevated stress and burnout [24,25], especially among caregivers [24].

- Organizational culture and collaboration. Hybrid teams require deliberate rituals and practices to preserve company culture, knowledge sharing, and mentoring. Virtual work can weaken informal social bonds and impede spontaneous collaboration, so managers must proactively address communication gaps [17]. Leadership style and trust have been shown to strongly moderate outcomes in distributed teams [26].

- Environmental and societal impact. Fewer commutes and less office utilization led to lower CO2 emissions, positioning hybrid work as a contributor to corporate sustainability and ESG goals [27].

1.2.3. Theoretical Lenses

Three theoretical frameworks dominate recent analyses of remote/hybrid work: (i) the Job Demands–Resources model, which posits that job autonomy and organizational support can buffer against technostress and overload [28]; (ii) Self-Determination Theory, which highlights employees’ needs for satisfactory autonomy, competence, and relatedness for optimal motivation [29]; and (iii) Social Exchange Theory, which explains how perceived organizational support fosters reciprocal commitment and engagement in low-monitoring environments [30].

Given that no single theory can fully encompass hybrid work’s complex psychological and organizational dynamics, this study constructs an integrated theoretical framework. Our approach relies on the complementary insights from the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model, Self-Determination Theory (SDT), and Social Exchange Theory (SET) to formulate hypotheses concerning stress, work efficiency, and the reciprocal relationships between employees and managers.

1.2.4. Research Gaps and Open Questions

Despite the breadth of recent literature, key gaps remain. Many studies have focused narrowly on the pandemic period and its immediate aftermath, without examining longer-term, post-pandemic dynamics. Crucially, most existing research lacks a comprehensive analysis of the optimal balance between remote and office work that integrates psychological aspects—particularly stress and burnout—and considers differences in perception between employees and managers. For instance, while remote work’s link to heightened stress and burnout has been documented [25], few studies incorporate these outcomes when evaluating work models. Comparative evidence on the “optimal” remote–office split is also scarce, particularly in the global IT sector [14], a bellwether for knowledge work. Existing studies typically (a) survey employees only, (b) focus on single countries, or (c) treat the notion of an “optimal balance” qualitatively rather than quantitatively. As a result, concrete benchmarks—e.g., what percentage of the workweek should be remote to maximize well-being and performance—are largely absent. This gap is problematic for policy design: misalignment between managerial expectations (often office-centric) and employee preferences (often flexibility-centric) risks causing disengagement, higher turnover, and sub-optimal utilization of office space [31].

1.2.5. Positioning of the Present Study

Responding to these gaps in the literature, the present study aims to deepen the understanding of remote and hybrid work models in the IT sector after the recent pandemic. In particular, our research considers dual stakeholder perspectives (comparing employees and managers) and incorporates stress and work efficiency indicators. We surveyed 1003 IT employees and 252 IT managers across 46 countries to (i) quantify their respective views to find the ideal share of remote work, according to the stress and productivity categories, and (ii) test perceptual differences in hybrid work effectiveness between employees and managers, given their distinct roles and communication needs. By integrating these elements and linking preferred work arrangements to tangible productivity and well-being metrics, the study advances the discourse on remote work from predominantly descriptive accounts toward actionable benchmarks for the post-pandemic workplace.

1.3. Research Objectives and Hypotheses

Grounded in SDT and the JD–R model, this study is guided by its primary objective:

- Determine the optimal balance between remote and office work in the IT sector, regarding perceived productivity and job satisfaction, and pursuing two interrelated objectives:

- o

- Compare perceived stress, efficiency, and effectiveness among IT employees in fully remote, hybrid, and full-office regimes.

- o

- Examine perceptual differences between employees and managers regarding hybrid work productivity and the adequacy of company-provided resources.

From these objectives, we derive the following hypotheses:

- Hypothesis DevelopmentThe Effect of Hybrid Work on Stress.

This hypothesis is grounded in the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model, which suggests that employee well-being depends on the balance between job demands and available resources. Within this framework, daily commutes and sustained office-based pressures function as significant job demands that can lead to stress. A hybrid model, by providing flexibility and reducing the number of commuting days, introduces a crucial job resource that helps to buffer these demands. While a fully remote model can introduce alternative stressors such as social isolation, a balanced hybrid approach is theorized to offer an optimal trade-off. It retains the benefits of in-person collaboration while mitigating the strain associated with a full-time office presence. We therefore offer the following hypothesis:

H1a:

Employees working in a hybrid regime will report lower perceived stress than those in remote or office regimes.

- The Effect of Hybrid Work on Efficiency.

This hypothesis is based on Self-Determination Theory (SDT), which posits that satisfying the innate psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness promotes optimal motivation and performance. Hybrid work models directly enhance autonomy by granting employees substantial control over where and when they work. According to SDT, fulfilling this need boosts intrinsic motivation, leading individuals to feel more engaged and effective in their roles. This heightened engagement is expected to translate into higher self-rated efficiency. While a fully remote arrangement maximizes autonomy, a hybrid model strategically balances this consideration with opportunities for in-person interaction, thereby also supporting the needs for competence and relatedness. This balanced approach, supported by prior findings linking part-time telecommuting to productivity gains, is expected to create an ideal context for peak perceived performance. We therefore offer the following prediction:

H1b:

Employees working in a hybrid regime will report higher perceived efficiency than those in remote or office regimes.

- Perceptual Gap in Hybrid Work Efficiency.

The second set of hypotheses addresses the potential perceptual gap between employees and managers. While employees may prioritize the autonomy and focus afforded by remote work, managers are responsible for broader outcomes such as team cohesion, spontaneous collaboration, and the maintenance of the organizational culture. The literature suggests that fully remote or poorly managed hybrid arrangements can hamper these collective aspects, creating challenges in informal learning, coordination, and knowledge sharing. This fundamental difference in roles and priorities can lead to a misalignment in how each group perceives the effectiveness of hybrid work. Managers, being more attuned to the potential loss of collaborative synergy, may be more sceptical of the overall efficiency of hybrid models compared to employees, who might focus more on completing individual tasks. This leads to our third hypothesis:

H2a:

Managers will perceive hybrid work as less efficient than IT-sector employees do.

- Perceptual Gap in Remote-Work Resource Adequacy.

Finally, we hypothesize a similar perceptual gap regarding the adequacy of company-provided resources for remote work. The JD-R model and literature inform this prediction relating to supervisor-optimism bias. From a managerial standpoint, resource allocation is often viewed from a policy level; once budgets are approved and tools are deployed, the organization has fulfilled its role of providing support. However, employees are the end-users who experience the daily functionality and potential frictions associated with these resources, such as network latency, inadequate hardware, or insufficient ergonomic support. This experiential gap can lead managers to overestimate the effectiveness and adequacy of the support provided. This phenomenon, in which supervisors rate flexible work initiatives more favourably than do their subordinates, is a documented bias in organizational research. We therefore predict that managers, being at a greater perceptual distance from the frontline experience, will evaluate remote-work resources more positively.

H2b:

Employees and managers will differ in their evaluation of company-provided remote-work resources. Guided by JD–R, we predict managers will report higher adequacy scores than employees.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This study employed a cross-sectional, quantitative survey design to investigate the perspectives of employees and managers in the IT sector on different work modalities. Data were collected through two parallel online surveys: one targeting employees, and the other targeting managers (including company owners and decision-makers).

The final sample consisted of 1255 participants from 46 countries, comprising 1003 employees and 252 managers and is described in Section 3.1.1.

A non-probability snowball sampling technique was utilized for participant recruitment. This method was chosen due to the absence of a comprehensive, publicly available sampling frame for the global IT sector workforce. Initial participants were identified through the authors’ professional networks and existing industry contacts. These contacts were then encouraged to forward the survey link to other eligible colleagues. This referral process allowed the sample to expand organically, effectively reaching a diverse and geographically dispersed group of professionals.

To mitigate the potential for selection bias inherent in snowball sampling, several steps were taken. First, the initial seed contacts were chosen with the intention of including a wide range of roles and locations. Second, mapped quotas were used to guide recruitment, aiming for representation across key geographical regions and areas of engagement within the IT sector. Finally, post-stratification weighting was applied to balance the territorial structure of the manager sample with that of the employee sample, correcting for an up to ±2.5% difference, thereby enhancing comparability between the two groups.

2.2. Sampling

Stratification for the quota-based snowball sampling was guided by the estimated global distribution of the IT workforce across key geographical regions (by digital maturity) and key job roles. A detailed description of the sources and rationale for this stratification is provided in Appendix A.1.

2.3. Survey Instruments and Measures

Data were collected using two tailored online surveys, developed for this study, which consisted primarily of closed-ended questions. A limited number of open-ended questions were included to gather qualitative insights, but they are not the focus of the quantitative analysis presented here. The key variables (constructs) required to test the study’s hypotheses were operationalized as specified in Table 1.

Table 1.

Instruments and variable construction.

Qualitative items were collected but not analysed; the study is therefore fully quantitative. The surveys were administered online using a professional survey platform between March and October 2024. Participants were provided with an information sheet that explained the study’s purpose and the voluntary nature of their participation and provided assurances of anonymity. Informed consent was obtained electronically before the commencement of the survey. The median time for survey completion was approximately 15 min.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was designed to test the predefined hypotheses by comparing outcomes across work modalities and stakeholder groups (employees vs. managers). The specific statistical tests, along with their rationale, are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Plan of statistical analysis.

Multiple testing: Each hypothesis targets a distinct, theory-driven research question; outcomes are non-overlapping, so the family-wise error rate was controlled by retaining the conventional significance threshold of α = 0.05. For the hypotheses with an explicit directional prediction (H1a—lower stress; H1b—higher efficiency; and H2b—higher resource adequacy), we report both the conventional two-tailed p-value and the one-tailed p-value corresponding to the predicted direction.

H2a was analysed in a two-tailed manner; the prior literature provides mixed evidence—some studies find that managers rate hybrid efficiency higher, others lower, than do employees—so we treated any deviation (positive or negative) as substantively interesting.

Chi-square tests and Cramer’s V for associations between office-attendance preference and demographics (Table 3).

Table 3.

Chi-square tests and Cramer’s V for association between the number of working days at work optimal/current and employees: total (between the Q7 and key demographic/work variables).

Software: Analyses were run in Python 3.10 (pandas 1.5, SciPy 1.11, stats models 0.14) and IBM SPSS 29 for the descriptive cross-checks.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality. The commissioning entity fully anonymized the dataset before it was transferred for analysis, with no personal identifiers being processed by the research team.

3. Results

This section presents the primary findings of the study, beginning with a description of the sample characteristics, followed by the results of the hypothesis testing.

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Sample Characteristics

3.1.1. Sample Characteristics

A total of 1255 valid responses were collected, comprising 1003 employees and 252 managers from the IT sector across 46 countries. The detailed demographic and contextual characteristics of these two subsamples are presented in Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 4.

Sample—Employees.

Table 5.

Sample—Managers.

As shown in Table 4, the employee sample (N = 1003) was drawn from a diverse range of company environments. Most employees (64.4%) worked in companies serving both B2B (Business-to-Business—B2B, where transactions occur between businesses) and B2C markets (Business-to-Consumer—B2C, transactions occur between businesses and individual consumers). The third modality was B2G (Business-to-Government—B2G, where transactions occur between companies and government entities). In terms of company size, the sample was dominated by employees from multinational corporations (MNCs) (55.7%), indicating a strong representation from large, global firms. The geographical distribution of the sample aligns with the study’s quota targets, with respondents primarily being from the USA (35.0%) and the EU (30.0%). Furthermore, a significant portion of employees (59.7%) were located in countries classified as having the most developed IT sectors, providing a robust dataset for analysing trends in mature digital economies.

The manager sample (N = 252), detailed in Table 5, was predominantly male (60.8%) and situated in the 36–45 (42.0%) and 46–65 (49.2%) age brackets. The sample provided a balanced representation across the organizational hierarchy, with the largest groups being the operational (39.3%) and tactical (33.7%) managers. This ensured that the findings captured perspectives from management levels directly responsible for team supervision and day-to-day operations.

3.1.2. Office Attendance Patterns

As a control variable for our objectives and hypotheses, we included the Office measure—“How many times per month would it be most convenient for you to go to the office?”—to account for individual attendance preferences. The descriptive distribution of this variable is reported in Table 6. According to the research results, employees in the IT sector currently (at the time of the research—from March to October 2024) come to work on average seven times out of approximately 20 working days per month (Table 6).

Table 6.

Number of working days at work, optimal//current: Employees (average).

We record statistically significant differences according to all observed characteristics of the IT sector employee population, namely, gender, age, education, area of work engagement, and time required for commuting. Thus, men go to work on average 7.5 times a month, while women go 6.2 times a month.

The largest differences are recorded according to the age of employees. In addition to the linear decrease in the frequency of going to work with age (18 to 25 years: 11.4 times; 26 to 35 years: 8.5 times; 26 to 45: 6.2 times; 46 to 65 years: 3.8 times), we emphasize that employees from the youngest category go to work/work from company premises exactly three times more days in a given month, compared to the oldest group.

Employees with a secondary education go to work on average 11.2 times a month, which is twice as much, compared to the categories of further education (5.5 times) and higher education (5.8 times).

We also record significant differences according to the area of work engagement (type of role): Employees in administration, finance, and resource management go to work the most (11.6 times a month). They are followed by those engaged in system architecture and design (8.3 times), software development (7.2 times), and sales/marketing (5.8 times). Program/project managers are the least likely to be present on company premises (4.3 times a month).

The frequency of going to work linearly decreases with the time required for commuting. Employees who spend up to 30 min commuting daily go to work 11.2 times a month, which is significantly more, compared to those who need up to 60 min (10.0 times), up to 90 min (9.2 times), and more than 90 min (8.0 times).

As we can see, proportionally, significantly fewer employees go to work in companies with more than 1000 employees (3.9 times a month) compared to smaller companies (up to 50 employees: 10.5 times a month; 51 to 300 employees: 10.8 times a month; 301 to 1000 employees: 11.4 times a month).

Territorially, the least work is performed from company premises when considering companies in the USA, with an average of 4.2 times a month, and the highest values are associated with those in EU candidate countries (11.6 times a month). Employees in the IT sector in EU member states go to work 8.7 times a month, while in other countries, employees in this sector go to work 7.2 times a month.

The frequency of working from company premises linearly decreases with the degree of IT sector development in the observed countries. According to the results of this research, it can be concluded with statistical reliability that the more developed the IT sector, the more oriented it is towards remote work. According to the degree of IT sector development, in countries from the “less developed” category (Emerging Digital Nations—EDN), employees go to work 10.6 times a month; in countries from the “moderately developed” category (Digital Adopters—DA), 8.4 times; and among the “most developed” category (Digital Leaders—DL), only 5.6 times a month.

On the other hand, employees in the IT sector on average state that the optimal (according to them) number of days going to work, i.e., the number they prefer, is about 8.1 days a month (practically one day more than the current average) Table 6).

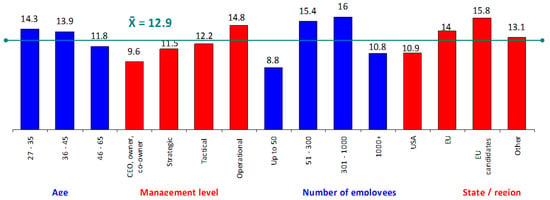

Managers in the IT sector go to work on average 12.9 days a month (Figure 1). The frequency of going to work linearly decreases with the age of managers (from 27 to 35 years: 14.4 times a month; from 36 to 45 years: 13.9 times a month; from 46 to 65 years: 11.8 times a month) and the level of management (general director/owner/co-owners: 9.6 times a month; strategic level: 11.5 times a month; tactical level: 12.2 times a month; operational level: 14.8 times a month).

Figure 1.

Number of office working days: Managers (average).

The optimal number of days going to work varies by gender (men 8.4 days; women 7.5 days—not statistically significant, see Table 6) and linearly decreases with age (up to 26 years, 11.7 days; up to 35 years, 9.2 days; up to 45 years, 7.2 days; over 46 years, 5.6 days) and the time needed for commuting (up to 30 min, 12.3 days; up to 60 min, 11.1 days; up to 90 min, 6.3 days; more than 90 min, 6.3 days—statistically significant).

Overall, fewer days from company premises would be thought optimal by those engaged in system architecture (−0.3 days) and those who need more than 90 min for commuting (−1.7 days), as well as those who already work from company premises 11 to 15 times (−0.3 days) or 16 to 20 times (−3.8 days) a month.

The largest positive difference, i.e., the assessment that more working days from company premises would be optimal, is recorded in sales/marketing (3.6 days) and among those who now come to work up to five times a month (3.1 days).

Territorially, among the IT sector employees worldwide who believe that working more days from company premises would be optimal compared to their current schedule, the majority are in the USA (1.3 days).

Also, employees in countries with the most developed IT industries, who now work from company premises on average 5.6 days a month, estimate that the monthly optimum for them is 6.9 days at work.

3.2. Objective 1—Stress and Efficiency Across Regimes

The following sections present the results of the formal hypothesis tests.

Hypothesis 1 (H1a and H1b): The Effect of Hybrid Work on Stress and Efficiency

Hypotheses H1a and H1b examined whether employees in a hybrid work regime report lower stress and higher efficiency, compared to those in fully remote or office-based regimes. The results are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Hypotheses H1a and H1b: Results of testing.

Hypothesis H1a received only marginal support; while the direction of the effect was as predicted, the result was not statistically significant at the conventional two-tailed α = 0.05 level. In contrast, Hypothesis H1b was strongly supported, indicating that employees in a hybrid regime are significantly more likely to perceive this model as the most efficient. These findings were robust to the inclusion of control variables in a logistic regression model.

3.3. Objective 2—Perceptual Gaps Between Employees and Managers

This set of hypotheses investigated the differences in perception between employees and managers regarding efficiency and resource adequacy.

3.3.1. Hypothesis H2a: Perceived Hybrid Efficiency

Hypothesis H2a posited that managers would perceive hybrid work as being less efficient, compared to their employee counterparts. However, the results revealed a significant effect in the opposite direction (Table 8).

Table 8.

Hypothesis H2a: Results of testing.

A considerably higher percentage of managers (31.0%) than employees (18.7%) singled out the hybrid model as the most efficient work arrangement. Formal statistical tests confirmed this observation.

H2a was rejected—managers are almost twice as likely as employees to single out the hybrid model as the most efficient arrangement.

3.3.2. Hypothesis H2b: Adequacy of Remote-Work Resources

Hypothesis H2b predicted that managers would rate company-provided remote-work resources more favourably than would employees. As detailed in Table 9, this prediction was strongly supported.

Table 9.

Hypothesis H2b: Results of testing.

H2b was supported—managers evaluate company support significantly more favourably.

3.4. Summary of Hypothesis Tests

The outcomes of the four primary hypotheses tested in this study are summarized in Table 10.

Table 10.

Summary of the hypothesis testing results.

The results confirm the employee-side benefit of light hybrid schedules (lower stress, higher efficiency) and reveal a perceptual gap in which managers consider hybrid work to be even more efficient and better resourced than the levels indicated in employee responses.

Taken together, these findings highlight both the personal stress/efficiency benefits of hybrid work (H1) and a stakeholder perception gap in which managers value hybrid even more strongly than employees do (H2).

4. Discussion

4.1. Synthesis of Key Findings

Our study set out to identify an empirically grounded “sweet spot” for hybrid work in the IT sector and to compare employees’ and managers’ perceptions of that model. Three core insights emerge:

- Light-to-Moderate Hybrid Reduces Stress and Boosts Efficiency. Employees on a hybrid regime (6–10 office days per month) were marginally less likely to locate stress in the office (H1a: OR ≈ 0.79, p ≈ 0.09) and were more than twice as likely to rate hybrid as most efficient (H1b: OR ≈ 2.12, p < 0.001). This aligns with prior evidence that part-time remote work can alleviate commuting strain while preserving collaboration benefits [21,22]. This “sweet spot” offers a clear illustration of the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model in action; the resource of flexibility is substantial enough to buffer the demand of commuting, without introducing the new demand of total social isolation. Concurrently, the strong boost in perceived efficiency supports Self-Determination Theory (SDT), as the enhanced autonomy over one’s work environment directly translates into higher intrinsic motivation and self-rated performance [29].

- Managers Overestimate Hybrid Benefits. Contrary to H2a, managers were nearly twice as likely as employees to single out hybrid as the most efficient model (OR ≈ 1.95, p < 0.001). They also rated remote-work resources more favourably (H2b: OR ≈ 2.64, p < 0.001). This extends relevant findings on supervisor-optimism bias in flexible-work initiatives [32] and suggests a disconnect between managerial expectations and frontline experience. This “supervisor-optimism bias” can be explained theoretically by the concept of perceptual distance. From a JD-R perspective, managers perceive the provision of flexible work as a major organizational resource and may be less aware of the daily operational demands their employees face. Their favourable rating of resources likely reflects their role in allocation rather than daily use, creating a disconnect between policy design and frontline experience, a phenomenon documented in prior flexible-work research [32].

- Burnout Risk Unrelated to Regime Alone. Our exploratory burnout proxy showed no clear association with office-day counts (ORs ≈ 1.2), indicating that exhaustion arises from complex demand profiles rather than location per se.

Together, these results confirm that a ∼40–60% on-site window is “safe” for balancing stress and efficiency, while also exposing a stakeholder perception gap that may undermine policy alignment.

4.2. Theoretical Implications

By weaving together Self-Determination Theory (SDT) and the Job Demands–Resources (JD–R) model, our findings suggest the following:

- Autonomy and Relatedness Trade-Off (SDT). Light-hybrid schedules preserve autonomy (choice of location) without severing relatedness—explaining the modest stress reduction and strong efficiency gains [29].

- Resource–Demand Imbalance for Employees (JD–R). Managers’ rosier ratings reflect their greater resource control and office exposure, skewing their resource/demand ratio positively [28]. Employees’ lower adequacy scores signal persistent resource deficits (e.g., desk availability, VPN reliability) that undermine the hybrid promise.

- Supervisor-Optimism Bias. The dual gap (efficiency and resource ratings) corroborates prior work showing that supervisors often overestimate the success of flexible-work initiatives, compared to subordinates [30].

This integrated framing advances hybrid-work theory by pinpointing where autonomy gains are offset by residual demands, and by highlighting the need to factor in stakeholder-specific resource perceptions.

4.3. Practical Implications for IT Organizations

Translating these insights into action requires IT leaders to adopt a multifaceted strategy. One primary implication is the need to move beyond one-size-fits-all mandates and instead tailor hybrid policies to specific job roles. Coordination-intensive functions, such as project management, may benefit from a greater on-site presence to foster collaboration, while deep-focus roles, like software development, could thrive with more remote work [18,19]. To ensure these tailored policies are effective, organizations must co-develop hybrid Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) with their teams. This aligns managerial expectations with employee realities by defining productivity through shared metrics, rather than relying solely on office attendance.

Furthermore, closing the perception gap requires tangible improvements to the employee experience. Leaders should conduct regular audits to equalize remote-work resources, addressing the shortfalls identified by nearly a fifth of employees in our study. This involves not just providing hardware stipends but also ensuring robust connectivity and ergonomic support. Finally, organizations must actively reduce hybrid friction by guaranteeing desk-booking availability on core collaboration days and offering commute subsidies or flexible hours, thereby extending the stress-reducing benefits of the hybrid model for all employees.

4.4. Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights, its limitations must be acknowledged. Firstly, the cross-sectional, self-report design means that causality cannot be definitively established, and findings related to productivity rely on perception rather than objective KPIs. Secondly, our four-item burnout proxy captures the core element of exhaustion but omits other facets, such as depersonalization. Future research would benefit from employing full, validated scales, such as the three-dimensional MBI (Maslach Burnout Inventory) or two-dimensional OLBI (Oldenburg Burnout Inventory). Finally, while quota-based stratification and post-weighting were used to mitigate bias, the snowball sampling technique may still limit the global generalizability of the findings beyond the surveyed population.

4.5. Future Research Directions

Future research could build upon the findings of this study in several key directions. To move beyond perceptual data, subsequent studies should triangulate findings with objective metrics, incorporating system-logged outputs such as commit counts or incident resolution times to validate productivity claims. Furthermore, employing longitudinal interventions would allow for the examination of causality; for instance, testing structured changes, such as desk-booking overhauls, in randomized controlled settings could reveal their direct impacts on employee outcomes. Finally, there is a significant opportunity to deepen the moderation analysis by exploring how variables such as job role, firm size, and the digital maturity of the business environment shape the complex relationship between hybrid work models and employee well-being.

A light-to-moderate hybrid model (~6–10 office days per month) emerges as the optimal balance for IT employees, delivering modest stress relief and strong efficiency gains. Managers—already operating near the office-heavy end—view hybrid even more favourably and assume resources are sufficient. Bridging this perceptual divide and eliminating remaining resource gaps are critical next steps for IT organizations aiming to sustain high performance and well-being in the post-pandemic workplace.

5. Conclusions

Building on Self-Determination Theory and the Job Demands–Resources model, this study set out to identify an empirically grounded “sweet spot” for hybrid work in the global IT sector. The findings reveal two core insights: the existence of an optimal hybrid window for employees and a systematic perception gap between employees and their managers.

Our results indicate that a schedule of 6–10 office days per month represents a balanced model for IT employees, delivering modest stress relief while significantly boosting perceived efficiency. It is important to move beyond uniform mandates and to tailor hybrid policies to specific job roles. Critically, this research uncovers a key “supervisor-optimism” bias: managers, who attend the office more frequently, perceive hybrid work even more favourably than employees and tend to overestimate the adequacy of remote-work resources.

This perceptual divide, likely driven by differing daily work experiences and control over resources, represents a key challenge for organizations. By aligning hybrid policies with specific role demands, co-defining success metrics to bridge the efficiency perception gap, and remedying resource shortfalls, IT organizations can fully harness the motivational and performance advantages of hybrid work, thereby fostering a more sustainable and productive post-pandemic workplace.

Author Contributions

M.L.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. J.V.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—review and editing. A.V.: Data curation, Project administration, Visualization. D.V.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision. R.L.: Methodology, Validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Faculty of Organizational Sciences, University of Belgrade, Serbia (Reference No: 05-02 no. 3/156 Date: 15 February 2024, in Belgrade).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank everyone who contributed to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Milos Loncar was employed by the company Microsoft Corporation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Sample Plan & Stratification

Appendix A.1.1. Overview

Appendix A.1 provides the full specifications of our quota-based snowball sampling design, ensuring transparency and reproducibility.

Appendix A.1.2. Sample Plan Considered Through the Lens of Country Maturity

The sample plan included the representation of respondents according to the following territorial units: USA, EU, EU candidate countries, and other countries. The term “EU candidate countries” refers to countries that have applied to join the European Union and are adopting EU laws and standards; these countries are often characterized by developing IT sectors. Based on the available sources for the year 2024, the following distribution of employees in the IT sector was derived:

- USA and Canada: ~35–40%. The USA has the largest share of the global IT workforce, with over 9.6 million workers engaged in various IT fields.

- European Union (EU): ~25–30%. The EU has 9.8 million ICT professionals. It is estimated that, globally, the EU accounts for 25–30% of the IT workforce, when considering a broader definition of ICT professionals, and including those on the user side (e.g., an IT department in a bank or manufacturing company).

- EU candidate countries: ~5–7%. EU candidates constitute a smaller but rapidly growing segment of the global IT sector. Their contribution is estimated at around 5-7% of the global IT workforce, thanks to growing outsourcing markets.

- Other countries (Asia, Latin America, Africa): ~25–30%. This includes IT centres like India, China, and Latin America, which together make up about 25-30% of the global IT sector. India leads in the outsourcing industry, while Africa and Latin America are experiencing rapid growth due to the rise of freelancing platforms and accelerated digital transformation.

Considering different levels of aggregation and categorization of terms in individual studies, the structure of the IT workforce shares according to these mapped territorial units was derived based on the following sources:

- CompTIA State of the Tech Workforce|Cyberstates 2024: This study focuses on the IT industry in the USA [33].

- Publication: ICT Specialists in Employment—Statistics Explained From 2013 to 2023 (Statistics Explained, 2024): This provides insights into the scope and structure of the market segments relating to IT professionals for EU countries and candidate countries. According to the methodology in this study, IT professionals are individuals capable of developing, managing, and maintaining ICT systems, for whom ICT represents the main part of their job (OECD, 2004), regardless of whether they are employed in IT sector or use IT technologies to perform professional activities in other sectors [34].

- Publication: ISC2 Cybersecurity Workforce Study 2024: Global Cybersecurity Workforce Prepares for an AI-Driven World: This study provides an analysis of global trends, especially in the field of cybersecurity [35].

- Deloitte Global Workforce Trends 2024: This study is based on aggregated data and estimates, considering territorial differences in the development of the IT industry and digital transformation [36].

Despite the lack of reliable data on the global distribution of IT professionals by territorial units, or a reliable sampling framework for the global population of IT industry employees, the distributions derived from these sources were used to guide the quota setting for the snowball sampling method, ensuring that the sample would broadly reflect the estimated global distribution across these key regions.

The results presented are sufficiently indicative and provide a reasonable basis for the study’s conclusions, in accordance with the defined research objectives, particularly when analysed through the lens of IT sector development. In this regard, all research results are presented according to the development of the IT sector in the countries from which the respondents come; following the Digital Maturity Model [37], these were determined as follows:

- Digital Leaders (DA): Australia, Canada, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland, United Arab Emirates (UAE), the United Kingdom, and the USA. These are the countries with the most advanced IT infrastructure, innovation ecosystems, tech exports, and digital economies. They have high internet penetration, strong cybersecurity frameworks, and world-leading tech companies.

- Digital Adopters (DA): Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, India, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Qatar, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia. These are countries with well-developed IT sectors and growing digital industries but that are not yet at the forefront of global tech leadership. They may rely on foreign technologies or have emerging innovation hubs.

- Emerging Digital Nations (EDN): Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Bulgaria, Costa Rica, Greece, Mexico, Montenegro, Peru, Puerto Rico, Russia, Serbia, and South Africa. These are countries that are rapidly developing their IT sectors but that still face challenges in infrastructure, skilled workforce, or digital inclusion. Their tech industries are growing but not yet globally competitive.

Given that countries with advanced indicators show faster IT industry growth due to innovations, government policies, and access to capital [38,39], the following indicators were used to classify countries by IT industry development: technological infrastructure, investments in research and development, quality of education in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), success of the startup ecosystem, government support, and global position in the IT industry [40]:

Technological infrastructure: The quality and availability of telecommunications networks (e.g., broadband, 5G), digital connectivity, and internet access. Countries with advanced infrastructure usually have better conditions for IT sector development.

Innovations and research: Investments in research and development (R&D), number of patents, and the presence of innovative technologies such as cloud technologies, artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, big data analytics, quantum computing and others. Countries with a strong R&D base tend to develop their IT industry faster [40].

Education in STEM fields: The quality of the education system, availability of technical education and IT talents, and the number of graduates in relevant fields. A high level of education fosters technological innovations and workforce competence [41]. The quality of technical education and the number of graduates in IT fields significantly impact IT sector development. Countries like China, India, and the USA produce many STEM graduates, which is a key factor in technological development [42].

Startup ecosystem: The number and success of tech startups, access to investments, venture capital funds, and support for entrepreneurship. Dynamic startup ecosystems often indicate rapidly growing IT sectors [39]. The success of startups and access to investments also play an important role. Countries with strong startup ecosystems, such as the USA and Israel, attract significant investments in the IT sector, thanks to support from venture capital funds [43].

Government support and policies: Government policies and strategies focused on digitalization, smart cities, innovations, and technological development. Countries that actively support their IT industry through subsidies, tax incentives, and regulations tend to have faster IT sector growth [38]. Government policies focused on digitalization, smart cities, and technological development enable accelerated IT industry growth. Initiatives such as the American “Raise the Bar” program for improving STEM education represent key strategies for strengthening the IT sector [42].

Global position in the IT industry: The presence of large international technology companies, as well their development centres (Amazon Web Services, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, etc.); technology hubs; and participation in the global IT market [44].

These classifications served as a “lens” for stratifying the collected sample data during analysis, allowing for comparisons of perceptions and behaviours based on the digital maturity of the respondents’ locations (as shown in the results tables).

Appendix A.1.3. Sample Plan Through the Lenses of Area of Engagement (Type of the Job) and Gender

The sample plan included the representation of respondents according to the area of their work engagement: Software Development, System Architecture, Project Management, Sales/Marketing, and Administration/Finance/Resource Management. These categories represent different functional roles within the IT sector, each with potentially distinct collaboration and in-person presence requirements. Globally, the IT sector has the following percentage distribution of job types, based on industry trends, global employment statistics, and market research:

Software (development/programming): ~45–50%. Globally, software development dominates, as it is the primary driver of technological advancement. This includes not only developers but also related positions such as Program/Product Managers, QA testers, DevOps and UX engineers, security specialists, etc.

System Architecture: ~10–15%. These roles are crucial in large companies and technology leaders that rely on complex systems. An increasing number of companies are investing in system architecture and design to optimize their operations.

Project Management: ~10–15%. The number of people engaged in project management in IT companies primarily depends on the size and complexity of active projects.

Sales/Marketing: ~20–25%. Sales and marketing are globally significant, especially for IT companies that produce software solutions (B2B, B2C, and B2G). This percentage tends to grow.

Administration/Finance/Resource Management: ~5–10%. These roles are less represented but necessary to support core functions. Their representation increases with the size of the company, but processes in administration and finance are becoming increasingly automated, reducing the need for the number of employees in these sectors.

Similar to the geographical lens, these job type categories were used to guide the quota setting during the snowball sampling process and served as a “lens” for analysing the collected data to identify differences in perspectives and behaviours across different roles (as shown in the results tables). This global distribution is derived from available sources and may vary by region. Given that there is no precise statistical distribution of employees by area of work engagement in the IT sector, for the purposes of this study, an estimate was made based on the following sources:

CompTIA (2024), State of the tech workforce 2024 [33]: This report provides a comprehensive overview of the global IT workforce. It focuses on the distribution of technical and business roles in the industry and contains data on employment, skill needs, and growing segments such as software development and security. Key insights: 45% of technical professionals work in IT companies, while 55% work in non-IT sectors using technology. The highest demand is for software developers, data specialists, and IT infrastructure management.

KPMG (2024), Global tech report 2024: Beyond the hype [45]: This report analyses how global technology companies achieve a balance between innovation, security, and value in a dynamic environment. The focus is on employment strategies and the distribution of work roles in sectors such as software development, cloud systems, and project management. It particularly highlights the increasing importance of resource management in IT companies and adaptation to new technologies and challenges in hiring qualified professionals.

World Economic Forum (2023), The future of jobs report 2023 [46]: Although broader in focus, this report provides relevant insights into future employment trends in the IT sector, including roles in software development, marketing, and digital transformation, and the potential of AI and cloud technology. The analysis includes predictions about future demand for software development and project management.

The study also considered other reports: Eurostat (2023) ICT specialists in employment—Statistics Explained [34],; Eurostat (2024)—ICT sector—value added, employment and R&D and European Institute for Gender Equality (2023) [47]. Employment prospects in the ICT sector and platform work on the structure of employees in the IT sector. According to these sources,

Percentage of employees in the ICT sector: In 2023, 9.8 million people in the EU worked in ICT professions, accounting for 4.8% of total employment. The highest share of ICT specialists was recorded in Sweden (8.7%), Luxembourg (8.0%), and Finland (7.6%), while the lowest shares were in Greece (2.4%), Romania (2.6%), and Slovenia (3.8%).

Distribution by sectors: The majority of employees in the ICT sector are engaged in software development, while a smaller part work in telecommunications and ICT equipment manufacturing.

Gender representation: Women make up about 20% of the ICT specialists in the EU, with the highest shares in Bulgaria (29.1%), Estonia (26.8%), and Romania (26.0%).

Employment growth: From 2011 to 2021, employment in ICT services increased by 52.8%, while employment in ICT equipment manufacturing decreased by 10.7%.

Although there are no statistically reliable measures of the number and structure of employees in the IT sector globally, data is available from the UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) and the ITU (International Telecommunication Union [48]. The SDG Digital Agenda professes to unlock commitments to leverage innovation and emerging technologies for a more sustainable, inclusive and responsible future, focusing on digital transformation and global demand growth for specific skills such as programming, data management, and cybersecurity. Also, for the assessment of the structures of employment in the IT sector, the following sources were considered: UNDP Digital Strategy 2022–2025 (UNDP, 2022) and SDG Digital Agenda (2024) [49,50].

Appendix A.1.4. Sample Plan Through the Lens of Company Size

For the purposes of this study, companies were classified by the number of employees, based on an international standardization set by the European Commission in 2003 (Commission Recommendation of 6 May 2003 concerning the definition of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises) 2003/361/EC [51] as follows:

Small enterprises: Companies with 1 to 49 employees.

Medium-sized enterprises: Companies with 50–249 employees.

The classification of large enterprises as “mid-sized large enterprises” (250–1000 employees), “conglomerates”, “multinational corporations”, or “corporate giants” (1000+ employees) is not defined by formal, internationally adopted statistical categories but based on the UNCTAD report from 2022 [52].). For the purposes of this study, large enterprises are classified as follows:

Mid-sized large enterprises (MSLE): More than 250 employees.

Multinational corporations (MNCs) or “corporate giants”: Thousands of employees and a significant share in the global market. They often have a complex structure, with branch offices worldwide.

These company size classifications were used as a “lens” for setting sampling quotas and analysing the collected data to investigate how company size influences work modalities and perceptions.

Appendix A.1.5. Sample Plan—Managers

In the context of the research conducted with IT company managers, the management structure separates ownership and executive functions from other management levels [53]. Management levels are determined as follows:

Chief Executive Officer (CEO), often the owner or co-owner. The highest level of responsibility and authority, a special category of management above the classic management levels.

Strategic management implements the goals set by the CEO, owners, and co-owners (e.g., regional director, sector director, financial director, and operations director).

Tactical management coordinates management at the sector level (e.g., sales manager, production manager).

Operational management focuses on daily task execution and directly supervises employees (e.g., supervisor, team leader).

These management levels served as a “lens” for stratifying the manager sample and analysing the associated responses to identify differences in perspectives based on the respondents’ positions within the organizational hierarchy (as shown in the results tables).

References

- Yang, E.; Kim, Y.; Hong, S. Does working from home work? Experience of working from home and the value of hybrid workplace post-COVID-19. J. Corp. Real Estate 2023, 25, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, K. The impact of COVID-19 on IT services industry—Expected transformations. Br. J. Manag. 2020, 31, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Habaibeh, A.; Watkins, M.; Waried, K.; Javareshk, M.B. Challenges and opportunities of remotely working from home during COVID-19 pandemic. Glob. Transit. 2021, 3, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Lucas, G.; Roll, S.C. Impacts of working from home during COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental well-being of office workstation users. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dockery, M.; Bawa, S. Working from Home in the COVID-19 Lockdown. BCEC Res. Rep. 2020, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- McPhail, R.; Chan, X.W.; May, R.; Wilkinson, A. Post-COVID remote working and its impact on people, productivity, and the planet: An exploratory scoping review. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 35, 154–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, N.; Tappin, D.; Bentley, T. Working from home before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for workers and organisations. N. Z. J. Employ. Relat. 2020, 45, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Golden, T.D.; Shockley, K.M. How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2015, 16, 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopus. Search Results for Literature on Remote Work; (dataset snapshot, April 2025); Elsevier Scopus Database: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Barrero, J.M.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J. The Evolution of Working from Home. Working Paper. July 2023. Available online: https://wfhresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/SIEPR1.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Stanford SIEPR. Hybrid Work is a “Win-Win-Win” for Companies, Workers, Study Finds. Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research Brief. 2023. Available online: https://siepr.stanford.edu/news/hybrid-work-win-win-win-companies-workers-study-finds (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Eurofound. Hybrid Work: Definition, Origins, Debates and Outlook. Working Paper WPEF23002. 25 May 2023. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/eurofound-paper/2023/hybrid-work-definition-origins-debates-and-outlook (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Vacchiano, M.; Fernandez, G.; Schmutz, R. What’s going on with teleworking? A scoping review of its effects on well-being. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0305567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, K.; Erumban, A.A.; van Ark, B. Productivity and the pandemic: Short-term disruptions and long-term implications. Int. Econ. Econ. Policy 2021, 18, 541–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N.; Liang, J.; Roberts, J.; Ying, Z.J. Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Q. J. Econ. 2015, 130, 165–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, S.; Pearce, A. COVID-normal workplaces: Should working from home be a “collective flexibility”? J. Ind. Relat. 2022, 64, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, M.; Leidenberger, J. COVID-19 as a window of opportunity for sustainability transitions? Narratives and communication strategies beyond the pandemic. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2020, 16, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N.; Han, R.; Liang, J. How Hybrid Working from Home Works Out. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 30292, 2022 (Revised 2023). Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w30292 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Alipour, J.V.; Fadinger, H.; Schymik, J. My home is my castle—The benefits of working from home during a pandemic crisis. J. Public Econ. 2021, 196, 104373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), UK. PwC UK Shifts Hybrid Working Balance Towards More In-Person Work. Press Release. 5 September 2024. Available online: https://www.pwc.co.uk/press-room/press-releases/corporate-news/pwc-uk-shifts-hybrid-working-balance-towards-more-in-person-work.html (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Graham, M.; Weale, V.; Lambert, K.A.; Kinsman, N.; Stuckey, R.; Oakman, J. Working at home: The impacts of COVID-19 on health, family–work-life conflict, gender, and parental responsibilities. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 938–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodini, A.; Leo, C.G.; Rissotto, A.; Mincarone, P.; Fusco, S.; Garbarino, S.; Guarino, R.; Sabina, S.; Scoditti, E.; Tumolo, M.R.; et al. The medium-term perceived impact of work from home on life and work domains of knowledge workers during COVID-19. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1151009. [Google Scholar]

- Laß, I.; Wooden, M. Working from Home and Work—Family Conflict. Work. Employ. Soc. 2023, 37, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.W.; Priestley, J.L.; Moore, B.A.; Ray, H.E. Perceived stress, work-related burnout, and working from home before and during COVID-19: An examination of workers in the United States. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211058193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harunavamwe, M.; Kanengoni, H. Hybrid and virtual work settings: The interaction between technostress, perceived organizational support, work–family conflict and work engagement. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2023, 14, 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabaso, C.M.; Manuel, N. Performance management practices in remote and hybrid work environments: An exploratory study. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2024, 50, e2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Yang, L.; Jaffe, S.; Amini, F.; Bergen, P.; Hecht, B.; You, F. Climate mitigation potentials of teleworking are sensitive to changes in lifestyle and workplace rather than ICT usage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2304099120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. A critical review of the Job Demands–Resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health; Bauer, G.F., Hämmig, O., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Shanock, L.R.; Wen, X. Perceived organizational support: Why caring about employees counts. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2020, 7, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallup. Hybrid Work Highlights: Employee Preferences vs. Employer Expectations. Gallup Workplace Research Report. 2024. Available online: https://www.gallup.com/workplace/ (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Carillo, K.; Cachat-Rosset, G.; Marsan, J.; Saba, T.; Klarsfeld, A. Adjusting to Epidemic-Induced Telework: Empirical Insights from Teleworkers in France. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 30, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CompTIA. State of the Tech Workforce 2024. Available online: https://www.comptia.org/content/research/state-of-the-tech-workforce (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Eurostat. ICT Specialists in Employment—Statistics Explained. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=ICT_specialists_in_employment (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- ISC2. Cybersecurity Workforce Study 2024: Global Cybersecurity Workforce Prepares for an AI-Driven World. Available online: https://www.isc2.org/Insights/2024/10/ISC2-2024-Cybersecurity-Workforce-Study (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Deloitte. 2024 Global Workforce Trends. 2024. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/Tax/us-tax-deloitte-2024-global-workforce-trends.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Deloitte. Digital Maturity Model: Achieving Digital Maturity to Drive Growth. 2018. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/Technology-Media-Telecommunications/deloitte-digital-maturity-model.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Ragnedda, M.; Muschert, G. The Digital Divide: The Internet and Social Inequality in International Perspective; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Granata, G.; Scozzese, G. The actions of e-branding and content marketing to improve consumer relationships. Eur. Sci. J. 2019, 15, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kuzior, A.; Kwilinski, A. Cognitive Technologies and Artificial Intelligence in Social Perception. Manag. Syst. Prod. Eng. 2022, 30, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. Raise the Bar: STEM Excellence for All Students. Press Release. 7 December 2022. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20221226024246/http:/www.ed.gov/stem?utm_content=&utm_medium=email&utm_name=&utm_source=govdelivery&utm_term= (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- SpringerOpen. Advancing the Transition to Open Access: Springer Nature’s 2022 OA Report. Available online: https://openaccessreport.springernature.com/2022/ (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Ardley, B.; McIntosh, E. Business strategy and business environment: The impact of virtual communities on value creation. J. Strategy Manag. 2019, 12, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG. Global Tech Report 2024—Beyond the Hype: Balancing Speed, Security and Value. Available online: https://kpmg.com/xx/en/our-insights/transformation/kpmg-global-tech-report-2024.html (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- World Economic Forum. The Future of Jobs Report 2023. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs-report-2023/ (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Eurostat. ICT Sector—Value Added, Employment and R&D. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=ICT_sector_-_value_added,_employment_and_R%26D (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- ITU; UNDP. Joint Report: Digital Development and Employment Indicators. 2024. Available online: https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-d/opb/ind/d-ind-ict_mdd-2024-3-pdf-e.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Digital Strategy 2022–2025. Available online: https://www.undp.org/publications/digital-strategy-2022-2025 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- ITU; UNDP. SDG Digital Acceleration Agenda. 2024. Available online: https://www.sdg-digital.org/accelerationagenda-resources (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Recommendation of 6 May 2003 concerning the definition of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (2003/361/EC). Off. J. Eur. Union 2003, L124, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. World Investment Report 2022: Large Multinational Enterprises and Their Role in Global Employment. Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. 2022. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2022_en.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Robbins, S.P.; Coulter, M. Management; Pearson: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 9781292215839. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).