Abstract

This study addresses a gap in hospitality research by investigating how employees’ perceptions of green intellectual capital (GIC) influence their satisfaction with both career and life. Although sustainability has become increasingly relevant in organizational strategies, limited research has examined how such job resources affect employees’ attitudes. Guided by the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) framework, the study proposes a model in which organizational embeddedness (OE) mediates the relationship between green intellectual capital (GIC) and satisfaction outcomes, while thriving at work (TAW) moderates this pathway. The analysis is based on data collected from 371 employees working in four- and five-star hotels in Turkey. Structural equation modeling was used to test the hypotheses. The findings show that positive perceptions of green intellectual capital (GIC) are associated with stronger embeddedness, which, in turn, enhances career and life satisfaction. Moreover, this indirect effect is more pronounced among employees who report higher levels of thriving. The results emphasize how sustainability-oriented practices can serve as meaningful resources that improve employee outcomes in the hospitality industry.

1. Introduction

The hospitality sector plays a vital role in national economies, including Turkey. Its success depends heavily on employees to maintain consistent service quality and customer satisfaction. As service expectations continue to rise, employee engagement has become a crucial factor in organizational effectiveness, particularly when workplace environments support emotional wellness and job satisfaction [1]. The growing emphasis on sustainability has driven hotels to adopt green intellectual capital (GIC), which integrates environmentally conscious practices across human, structural, and relational dimensions. According to the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) theory, such organizational resources enhance motivation and engagement by equipping employees with relevant competencies and aligning their values with broader sustainability goals [2,3]. Following the COVID-19 outbreak, hospitality businesses were compelled to replan their operations to simultaneously address sustainability concerns and maintain workforce well-being [4]. However, continuing economic instability has made talent retention increasingly difficult, leading to staff downsizing and rising turnover [5,6,7]. In spite of these challenges, retaining experienced employees remains strategically essential, as their presence directly affects service quality, customer loyalty, and brand strength [8]. In this context, GIC is not merely a symbolic alignment with green values but a practical mechanism that shapes employee perceptions and behavior [9]. When sustainability is embedded into daily operations and professional development programs, employees are more likely to find purpose in their roles, boosting motivation and shared meaning [9,10]. The JD-R theory posits that resources like GIC serve not only to mitigate the effects of job demands but also to foster intrinsic motivation leading to higher levels of satisfaction, performance, and commitment [5]. In particular, stronger perceptions of GIC have been associated with increased career satisfaction (CS) and job satisfaction (JS), as employees feel their environmental values are respected and mirrored by the organization.

This study aims to offer a broader understanding of employee well-being by incorporating CS and life satisfaction (LS) as key outcome variables associated with perceived GIC. While CS represents how individuals evaluate the alignment of their career with personal values and goals, LS reflects a more holistic sense of well-being, often rooted in meaningful and ethically aligned work [11,12]. Recent scholarship highlights that organizational support, value congruence, and access to resources are key contributors to both CS and LS, especially in sustainability-oriented work environments [13,14]. Additionally, organizational embeddedness (OE) and thriving at work (TAW) have been found to amplify satisfaction by promoting psychological safety, purpose, and resilience, all of which are essential to sustainable HR strategies [15,16,17].

Although OE is traditionally described in terms of perceived fit, social ties, and anticipated sacrifices [18], this study adopts a global conceptualization of OE, referring to employees’ overall embeddedness in eco-conscious organizations. TAW, described as a dual psychological state involving vitality and continual learning, intersects meaningfully with GIC [17,19,20]. Employees who feel energized and intellectually stimulated are more likely to integrate environmental knowledge into their professional identity and derive satisfaction from their work [17].

Building on the JD-R theory, this study conceptualizes GIC as a sustainability-oriented job resource that fosters employee motivation and satisfaction [21,22]. The inclusion of OE and TAW addresses gaps in the literature by focusing on how employees’ perceptions of sustainability-related practices influence their sense of embeddedness and satisfaction, especially in service-driven settings. Building on the JD-R theory, this study conceptualizes GIC as a sustainability-oriented job resource that stimulates employee motivation and satisfaction. The inclusion of OE and TAW responds to gaps in the literature that call for understanding how green organizational climates translate into psychological response and well-being outcomes in service-intensive environments.

This study explores the interconnections among GIC, OE, TAW, CS, and LS to understand how sustainability-driven HR strategies influence employee satisfaction and retention. Framed within the JD-R theory, the research emphasizes hotel employees’ perceptions of GIC as a workplace resource that contributes to organizational sustainability and workforce well-being.

Unlike earlier work that primarily linked GIC to firm-level innovation and performance [23,24], these studies have not examined employees’ subjective perceptions of GIC. Our study fills this gap by emphasizing how GIC is perceived by employees in their day-to-day work, and how these perceptions influence their satisfaction and embeddedness. When GIC is aligned with employees’ own values and strengths, they tend to exhibit a higher level of OE. This embeddedness, viewed as a global construct in this study, reflects employees’ overall sense of organizational attachment and intention to remain within the organization. OE serves as a motivational channel through which GIC leads to higher CS and LS, as employees feel secure, valued, and fulfilled in both professional and personal spheres. As such, the study expands the function of GIC from a strategic environmental asset to a psychological mechanism fostering sustainable employee satisfaction and retention in hospitality settings [25].

Moreover, the study reframes OE not merely as an outcome of management practices or contextual factors [26,27], but as a response triggered by employees’ perceptions of sustainability-oriented organizational resources. In this perspective, GIC enhances employees’ overall sense of embeddedness, reflecting their perceived alignment with organizational values, connectedness, and intention to remain with the organization [10,18].

The research also shifts attention from organizational strategies or customer-facing outcomes toward employees’ experiences. While the prior hospitality literature often centers on consumer satisfaction, CSR, or regulatory frameworks [20,28,29], this study adopts a human-centered lens by examining how employees internalize sustainability through GIC. It uncovers how their perceptions of GIC shape both CS and LS, offering insights into how sustainability resources fuel meaning, motivation, and job satisfaction in demanding service roles.

In addition, this study introduces TAW as a moderating factor in the link between GIC and employee outcomes. While TAW has been previously associated with psychological resources, performance, and resilience [30], few studies have examined its amplifying role in sustainability contexts. Recent findings suggest that TAW enhances how available resources translate into organizational attitudes like commitment and OE [31,32]. However, little is known about how TAW interacts with sustainability-oriented constructs like GIC. This study addresses that gap by proposing, through the JD-R theoretical lens, that TAW moderates the relationship between GIC and employee outcomes, specifically OE, CS, and LS. Drawing on the JD-R model, employees with high levels of vitality and learning are more likely to convert sustainability-based resources into positive attitudinal outcomes, thereby strengthening the effects of GIC on OE, CS, and LS [17,19,30].

Finally, the study advances the literature by positioning OE as a distinct outcome of sustainability-based resources within the JD-R framework. Previous studies have explored job embeddedness in relation to organizational commitment and job satisfaction during crises [33], as well as trait activation theory to explain how employees’ perceived environmental alignment enhances their embeddedness, satisfaction, and intention to stay. In doing so, it contributes to a sustainability-centered model for retention, which is particularly relevant in addressing labor shortages in the hospitality sector [5,33].

The upcoming sections detail the theoretical framework, hypotheses, research methods, and data collection procedures, followed by findings, interpretations, and practical implications for both academics and hospitality practitioners.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

This research builds upon the JD-R theory, which explains employee well-being and performance as outcomes of the dynamic interaction between job demands and available resources [34]. Within this framework, job resources such as autonomy, supportive structures, and developmental opportunities are recognized as key drivers of motivation, resilience, and satisfaction [34,35,36]. In high-contact and labor-intensive settings like the hospitality sector, strategically designed job resources play a crucial role in maintaining both CS and LS [37].

In this study, GIC is conceptualized as a perceived job resource, reflecting how employees individually experience and interpret green values, systems, and stakeholder relationships in their daily work. In this context, GIC is conceptualized as a multidimensional construct composed of green human capital (e.g., environmental knowledge and values), green structural capital (e.g., eco-supportive systems), and green relational capital (e.g., trust-based stakeholder relationships grounded in sustainability) [9,10,21]. These components represent how environmental values are embedded into organizational processes. Studies such as Shazali et al. [38] emphasize the importance of GIC in developing economies, where it enables resource access and promotes environmentally aligned tools, which in turn enhance employee outcomes [23,30].

Framed within the JD-R model, GIC operates as a sustainability-oriented job resource that fosters stronger OE. When employees perceive high levels of GIC, they are more likely to identify with the organization’s environmental values and practices, which contributes to favorable attitudes and enhanced satisfaction [21,39].

Although OE is traditionally conceptualized with three dimensions—fit, links, and sacrifice—as proposed by Mitchell et al. [18], this study adopts a unidimensional, global approach, drawing on the scale developed by Crossley et al. [40].

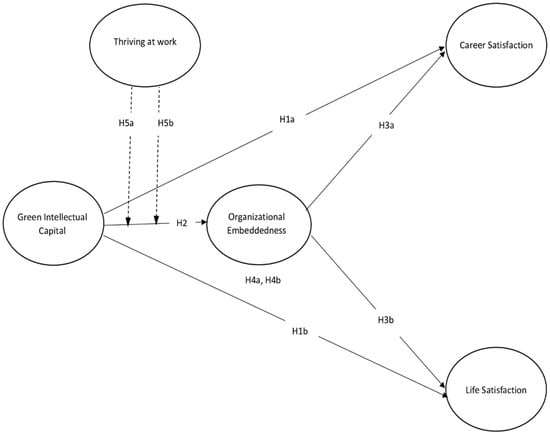

Similarly, TAW is treated as a unidimensional construct in this study, representing an integrated psychological state encompassing both vitality and learning. Although prior studies have distinguished these as separate dimensions [19], recent research suggests that the dynamic interplay between the two reflects a unified thriving experience in practice [30]. Therefore, this study conceptualizes TAW as a unidimensional psychological perception encompassing both vitality and learning, as recommended by recent studies [30,41]. Rather than analyzing these subdimensions separately, we focused on the integrated perception of thriving, which reflects employees’ subjective psychological response to sustainability resources. By integrating GIC into the JD-R framework, this research proposes a resource-based pathway through which sustainability-oriented practices enhance employee satisfaction outcomes. OE serves as a mediator, linking GIC to both CS and LS. The conceptual model presented in Figure 1 illustrates these relationships in the context of service-oriented organizations.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework of the study.

2.2. Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. Direct Effects

GIC supports value congruence between employees and their organizations by enabling access to sustainability-oriented training, environmental innovation, and practices that foster a psychologically supportive work environment [28,42]. When employees perceive their workplace as environmentally responsible, this alignment enhances motivation, commitment, and ultimately satisfaction core mechanisms within the JD-R model [34].

Prior research provides empirical evidence that GIC is positively associated with job-related and personal outcomes. For instance, Dumont et al. [22] found that employees’ perceptions of organizational green practices reflected through GIC can enhance satisfaction levels. Similarly, Shahbaz and Malik [42] demonstrated that GIC significantly predicts sustainable firm performance through its positive effect on employee attitudes and behaviors. Moreover, Liao et al. [43] emphasized that corporate social responsibility initiatives grounded in GIC increase work meaningfulness and life satisfaction. These studies highlight the potential of GIC to foster ethical congruence and a deeper sense of purpose among employees, two critical factors for career and life satisfaction.

In addition, Yusliza et al. [21] revealed that green human and structural capital have a positive impact on internal stakeholder well-being, confirming that GIC functions as a sustainability-based job resource that nurtures personal fulfillment. Likewise, evidence shows that green-oriented resources strengthen employees’ job embeddedness, innovative behavior, and satisfaction in hospitality and service contexts [44,45,46]. Therefore, based on this growing body of empirical evidence and aligned with the JD-R theoretical framework, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1.

GIC has a positive effect on CS (a) and LS(b).

In the current study, GIC is conceptualized as an integrated strategic asset that encapsulates how employees perceive their organization’s environmental commitment across human competencies, organizational infrastructure, and stakeholder relationships [21,47]. Instead of analyzing green human, structural, and relational capital separately, this study adopts a holistic approach to GIC by treating it as a unified construct. This reflects how employees perceive the organization’s overall environmental orientation in practice, rather than as isolated components. Recent studies have similarly conceptualized GIC as an integrated resource, demonstrating that its combined influence shapes attitudinal outcomes such as satisfaction and organizational attachment [9,10,21].

GIC is expected to enhance OE by fostering perceived fit, strong organizational ties, and the sense of personal cost associated with leaving [18]. When sustainability is embedded in HR systems, routines, and value structures, employees perceive greater alignment between their values and the organization’s mission, which can strengthen their OE. Previous research has shown that environmental value congruence contributes to stronger organizational commitment and embeddedness [20,48], and that perceived organizational justice also strengthens embeddedness and performance in hotel settings [49].

Taken together, these theoretical arguments and empirical findings suggest that GIC plays a critical role in fostering OE by aligning environmental values and organizational identity.

Based on this theoretical and empirical grounding, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2.

GIC has a positive effect on OE.

According to the JD-R theory, such embeddedness arises when organizational resources enhance employees’ sense of fit, interpersonal connections, and the perceived cost of leaving the organization. In this study, OE is treated as a global construct that reflects employees’ overall connection to an organization’s environmentally embedded systems and values [18,34].

When employees experience higher levels of OE, they tend to feel more secure and supported in their professional roles, which increases their commitment to career goals and satisfaction with career progression.

In the hospitality industry, where work environments are often emotionally demanding and require strong relational bonds, embeddedness becomes particularly relevant. Embedded employees are more likely to experience workplace stability and role clarity, both of which are critical for CS in high-pressure service contexts [16,50]. Furthermore, when employees perceive a stable and meaningful connection to their organization, this sense of continuity can spill over into their personal lives, fostering a stronger sense of coherence and fulfillment beyond the workplace. Such dynamics are essential contributors to overall LS, especially in sectors where professional identity plays a large role in shaping personal well-being [37].

Based on this theoretical grounding and empirical support, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3.

OE has a positive effect on CS(a) and LS(b).

2.2.2. Mediating Role

OE operates as a mediating mechanism that explains how job resources give rise to favorable employee outcomes. Rather than being viewed solely as an outcome, OE encompasses employees’ attachment to their organization, expressed through value alignment, social bonds, and the perceived cost of departure [18]. In this study, GIC is approached as a unidimensional construct, representing employees’ perceptions of their organization’s commitment to environmental responsibility. These perceptions may foster a sense of alignment with organizational values, reinforce role support, and promote deeper engagement at work.

While prior research has established direct associations between GIC and outcomes such as job and life satisfaction [21,23,42], the potential mediating function of OE in this relationship remains insufficiently examined. Evidence indicates that employees who are more embedded tend to experience stronger emotional connections, enhanced meaning in their roles, and a deeper sense of organizational identity, particularly within high-pressure service environments like hospitality [18,35]. These attributes are closely tied to improved satisfaction and reduced intention to leave.

Therefore, this study proposes that OE functions as a motivational channel through which GIC influences both CS and LS. When employees perceive that their organization’s green values resonate with their own, they are more inclined to develop a stronger sense of belonging and commitment, factors that enhance overall professional and personal well-being. Based on this rationale, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4a.

OE mediates the relationship between GIC and CS(a) and LS(b).

2.2.3. Moderating Effects

TAW is defined as a psychological state characterized by vitality and learning, enabling employees to actively grow, adapt, and stay engaged in dynamic organizational environments [17,19]. Within the JD-R framework, personal resources such as TAW are theorized to amplify the motivational impact of job resources like GIC [34]. Employees who thrive are more likely to integrate sustainability-focused initiatives with their personal values and engage more meaningfully with their organization’s green vision.

Employees with high TAW are generally more adaptable and resilient, which enables them to better process and internalize sustainability-related resources such as GIC. This finding is consistent with previous research highlighting the role of TAW in enhancing employees’ capacity to utilize complex job resources effectively [19,41]. This heightened sense of alignment between employees and their organization enhances OE, which in turn fosters greater career and life satisfaction [41]. Conversely, employees with lower levels of TAW may lack the vitality and cognitive flexibility needed to derive benefits from GIC.

Although existing research has examined the influence of TAW in relation to general organizational support and engagement outcomes, its moderating role in green work settings remains underexplored. Notably, Slatten et al. [51] demonstrated that TAW functions as a moderator in multifaceted organizational processes, specifically by strengthening the indirect effects of antecedent variables through mediators such as employee ambidexterity and innovation behavior.

Based on this rationale, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5a.

The indirect effect of GIC on CS via OE is stronger when TAW is high.

H5b.

The indirect effect of GIC on LS via OE is stronger when TAW is high.

3. Methodology

This study employs a deductive research approach, which is based on a structured framework aimed at testing hypotheses derived from established theories [52]. The choice of a deductive method aligns with the study’s objective of generating empirical evidence to contribute to the knowledge base within the field. A structured questionnaire was carefully designed and administered to collect the necessary data for this study. The sample consisted of hotel employees working in three of Turkey’s leading tourism provinces. The sample consisted of hotel employees, including both frontline and back-office staff, working in three of Turkey’s leading tourism provinces. To facilitate data collection efficiently, the researchers adopted a convenience sampling approach, enabling them to reach participants who were readily accessible across these tourism regions [23,53].

This non-probability sampling technique is widely recognized for its practicality, particularly when access to the target population is limited or when time constraints are present [54]. It allows researchers to collect responses in a cost-effective and timely manner until the desired sample size is achieved [55]. Additionally, following previous research on TAW [23,56,57], this study identified convenience sampling as an appropriate and effective technique for obtaining participant responses.

This study focuses on the hospitality sector due to several important factors. It specifically selected four- and five-star hotels located in key tourist destinations, including Istanbul, Antalya, and Muğla, as designated by the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism [58]. These cities attract a substantial number of tourists, positioning them as ideal settings for examining customer-service interactions. The hotels involved in this study were selected from the official database of the Directorate of Certification and Development of Tourism Enterprises, a division of the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Specifically, surveys were distributed to 35 hotels, of which 9 provided valid responses. A total of 373 questionnaires were collected, and 371 were deemed usable for analysis. The valid responses were obtained from employees working in 9 hotels located across three key regions: Antalya (4 hotels; 2 five-star and 2 four-star), Muğla (2 hotels; 1 five-star and 1 four-star), and İstanbul (3 hotels; 2 five-star and 1 four-star). Data collection was coordinated in collaboration with hotel management to facilitate a seamless survey process. Employees were asked to complete the survey through an online questionnaire hosted on Google Forms, which was distributed via the hotel’s Enterprise Social Media (ESM) system. Among the responses, 2 were removed due to incomplete answers, leaving 371 valid responses, resulting in an effective response rate of 97.6%, which is considered highly satisfactory in social science research [59].

The study applied several methodological controls, following the recommendations of Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff [60], to minimize the risk of common method bias. That is, participants were assured that their involvement was entirely voluntary, ensuring they did not feel pressured to respond. They were also informed that there were no right or wrong answers, encouraging authentic and spontaneous responses, which enhanced the reliability and accuracy of the collected data.

In line with the hypothesized model, the visual presentation (see Figure 1) reflects a partial mediation structure, as the direct paths from GIC to satisfaction outcomes remain significant alongside the indirect paths via OE. This structure follows standard mediation modeling conventions, in which full mediation implies the absence of a direct path, while partial mediation includes both direct and mediated effects [61,62].

3.1. Measurement Items

The study variables were measured using well-established scales derived from prior empirical research. The survey was initially designed in English and later translated into Turkish, followed by a back-translation into English to ensure accuracy and consistency in meaning. The Cyprus International University Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee granted official approval for the questionnaire.

A pilot test was conducted with 20 hotel employees to evaluate the clarity of the survey items, confirming that the wording was clear and did not require any modifications.

GIC was assessed using Chen’s multidimensional scale [9], comprising green human capital (5 items), green structural capital (8 items), and green relational capital (5 items); however, consistent with our conceptual model, the construct was treated as unidimensional in the analysis.

OE was measured using the global scale developed by Crossley et al. (2007) [40], which captures employees’ overall attachment to the organization.

TAW was assessed using 10 items from Porath, Spreitzer, Gibson, and Garnett [19], capturing two core dimensions: learning and vitality.

LS was measured using the five-item scale developed by Diener, Emmons, Larsen, and Griffin [12]. CS was measured with five items adapted from Greenhaus, Parasuraman, and Wormley [11]. Both scales were previously implemented in the study by Karatepe and Karadas [37], ensuring validity and reliability.

3.2. Statistical Technique

The following section presents the statistical techniques used to examine the relationships among the study variables and assess the validity and reliability of the measurement model. The demographic variables of the respondents who provided the data for this study can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic profile.

A priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1 to determine the minimum required sample size. Assuming a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15), a significance level of α = 0.05, and a statistical power of 0.80, the analysis suggested a minimum sample size of 92 participants. Our sample of 371 respondents therefore exceeds this threshold, ensuring adequate statistical power for hypothesis testing.

SmartPLS is a specialized software tool developed to perform partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), a statistical method designed to evaluate complex relationships between latent constructs and observed indicators [59].

To address potential common method bias (CMB), we applied both procedural and statistical remedies. Procedural measures were taken in line with Podsakoff et al. [63], while statistically, we employed the full collinearity variance inflation factor (VIF) approach as suggested by Kock [64]. The results did not indicate any serious concern regarding CMB.

4. Data Analysis Results

In this research, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was employed to examine all measurement items. Convergent validity, discriminant validity, and composite reliability were assessed to verify that each construct and its indicators met accepted statistical standards (Table 2). The evaluation followed established guidelines for PLS-SEM [59], incorporating multiple metrics to assess the robustness of the measurement model.

Table 2.

Validity and reliability assessment.

SmartPLS 4.0 was selected for structural equation modeling due to its flexibility in handling complex models, non-normal data distributions, and its suitability for exploratory research with moderate sample sizes [59]. PLS-SEM is also appropriate for models involving both mediation and moderation, which aligns with our conceptual framework [59].

The findings revealed that all outer loadings surpassed the recommended threshold of 0.5, indicating that each item significantly contributed to its respective latent variable. Additionally, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values for all constructs exceeded the minimum benchmark of 0.5, confirming that a substantial portion of indicator variance was captured by their associated constructs.

Internal consistency was further supported by composite reliability (CR), Rho-A, and Cronbach’s alpha values, all of which were above the acceptable level of 0.7. These results collectively indicate that the measurement model used in the study is statistically sound and that the latent constructs accurately reflect the underlying theoretical concepts.

Discriminant validity evaluates whether each construct in the model is conceptually and statistically distinct from the others. Its establishment is critical, as it confirms that a construct’s indicators are unique and do not significantly overlap with those of other constructs in the model. According to the Fornell–Larcker criterion [65], discriminant validity is demonstrated when the square root of a construct’s Average Variance Extracted (AVE) exceeds its correlations with other constructs.

Table 3 presents these results, showing that for most constructs, the square root of the AVE (bolded in the table) is higher than the inter-construct correlations except in the case of GIC. These findings largely conform to the Fornell–Larcker guideline, suggesting that each construct is more strongly correlated with its own indicators than with others in the model.

Table 3.

Inter-construct correlations and discriminant validity.

These results were further supported by examining the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio, which provided additional evidence for discriminant validity [59]. As shown in Table 3, the italicized HTMT values, positioned above the square root of the AVEs, satisfy this criterion. These findings collectively confirm that the measurement model meets the discriminant validity criteria, ensuring that each construct remains statistically distinct and does not exhibit excessive overlap with others.

SEM was utilized to evaluate the relationships among the constructs in this study. The statistical significance of these relationships was evaluated using key metrics such as the Beta coefficient (β), t-values, and p-values. The detailed results of the path analysis are provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Hypothesis testing.

Furthermore, the model’s explanatory power was evaluated using R2, Q2, and f2 values. The R2 values for CS, LS, and OE were 0.452, 0.438, and 0.317, respectively, indicating moderate explanatory power. The Q2 values (CS = 0.291, LS = 0.285, OE = 0.241) confirmed predictive relevance. Effect sizes (f2) ranged from 0.012 to 0.197, indicating small-to-moderate effects across paths [59].

First, the results demonstrate that GIC has a significant direct positive effect on both CS (β = 0.088, t = 4.456, p = 0.000) and LS (β = 0.089, t = 4.441, p = 0.000), thereby supporting H1a and H1b. Second, GIC is also found to significantly affect OE (β = 0.095, t = 4.535, p = 0.000), confirming H2. Furthermore, OE exerts a significant positive influence on both CS (β = 0.026, t = 35.231, p = 0.000) and LS (β = 0.019, t = 47.748, p = 0.000), lending support to H3a and H3b.

In addition, mediation analysis confirms that OE mediates the relationship between GIC and both CS (β = 0.088, t = 4.456, p = 0.000) and LS (β = 0.089, t = 4.441, p = 0.000), supporting H4a and H4b.

Lastly, the moderated-mediation role of TAW was tested. The results show that the indirect effect of GIC on CS via OE is significantly stronger when TAW is high (β = 0.091, t = 3.247, p = 0.001). Similarly, the conditional indirect effect of GIC on LS via OE is also stronger under high levels of TAW (β = 0.092, t = 3.285, p = 0.001). These results provide strong support for H5a and H5b.

In terms of model fit, the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) was recorded at 0.072, which falls within the acceptable range (below 0.08). This suggests that the model adequately fits the data, as recommended by Hair et al. [59].

This study, grounded in the JD-R theory and analyzed using the SEM, examined a moderated-mediation conceptual framework to analyze the interrelationships among employees’ perceptions of GIC, OE, CS, LS, and TAW. Data were collected from employees working in Turkish hotels, and the results provide strong empirical evidence supporting all proposed hypotheses, reinforcing the validity of the conceptual model.

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Findings

This study examined how employees’ perceptions of GIC influence their CS and LS, and whether OE and TAW serve as underlying mechanisms within this process.

The findings first confirmed the direct effects of GIC on both CS and LS (H1a and H1b), indicating that employees who perceive their organizations as environmentally responsible report greater satisfaction in both career and life domains. Similarly, GIC was found to have a significant positive impact on OE (H2), suggesting that sustainability-oriented resources strengthen employees’ sense of organizational attachment. In turn, OE was positively associated with both CS and LS (H3a and H3b), underscoring its role as a key motivational outcome within the JD-R framework.

Moving beyond direct effects, the results supported the mediating role of OE (H4a and H4b). Specifically, OE partially mediated the relationship between GIC and both satisfaction outcomes, suggesting that GIC not only influences satisfaction directly, but also indirectly through enhancing employees’ embeddedness. This partial mediation pattern is consistent with the JD-R theory, in which organizational resources foster internalized work attitudes that contribute to broader well-being outcomes.

Finally, the analysis revealed moderating effects of TAW (H5a and H5b). The indirect effects of GIC on CS and LS via OE were significantly stronger for employees with higher levels of TAW. This implies that thriving individuals, those who are energized and engaged in learning, are more capable of converting green-oriented organizational resources into deeper organizational ties and, consequently, higher satisfaction levels. These findings emphasize the interplay between organizational and personal resources in shaping positive employee outcomes within sustainability-focused settings.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This research extends the JD-R theory by conceptualizing GIC as a pivotal sustainability-driven job resource that enhances OE and satisfaction among hotel employees in service-intensive hospitality settings. GIC, positioned here as a multidimensional construct encompassing HC, SC, and RC [9,10], broadens the existing typology of job resources to include environmentally embedded organizational elements.

The findings indicate that sustainability-oriented resources such as GIC function as motivational enablers, which is consistent with the JD-R model [34]. These resources foster employee engagement and alignment with organizational sustainability goals, two factors that significantly influence both career and life.

From a theoretical standpoint, this study advances JD-R theory by positioning OE as a key motivational pathway that explains how GIC translates into enhanced satisfaction. Practically, it highlights the role of perceived sustainability practices in promoting organizational embeddedness and well-being [16,18]. This reconceptualization advances the JD-R framework by positioning OE as a motivational force grounded in sustainability alignment, rather than viewing it exclusively as a product of managerial control or job design [26].

The inclusion of TAW as a moderating personal resource adds further depth to the model. The findings suggest that employees characterized by high levels of vitality and learning orientation are better equipped to internalize and benefit from sustainability-related organizational efforts. TAW strengthens the effect of GIC on OE, CS, and LS, revealing its role in amplifying the utility of job resources [19,41]. This interaction between job and personal resources responds directly to ongoing calls in the JD-R literature for more dynamic, multilevel investigations into employee motivation processes [34].

Overall, this study offers a fresh perspective by weaving sustainability into the fabric of the JD-R framework. It joins ongoing academic dialogues that emphasize embedding environmental values into employee experience strategies [20,28].

5.3. Managerial Implications

This study offers practical guidance for hospitality managers aiming to align employee satisfaction with environmental sustainability goals.

First, our findings indicate that investing in GIC has a direct and significant impact on employees’ CS and LS. Managers can enhance green human capital by implementing structured sustainability training modules, mentoring systems focused on eco-values, and performance metrics that reward green innovation. These investments help employees perceive their organization as purpose-driven, which can foster satisfaction and retention.

Second, GIC was found to positively influence OE, highlighting the value of sustainability in shaping employees’ emotional bonds with their workplace. Incorporating environmental values into daily work life, not just as policy but as part of the organizational identity, can enhance perceived alignment and increase employees’ sense of belonging.

Third, employees with higher levels of OE also report greater CS and LS. Hospitality managers should actively foster organizational environments that strengthen employees’ overall sense of connectedness, alignment with the organization’s values, and psychological attachment factors that contribute to embeddedness and, ultimately, satisfaction.

Fourth, the study confirms that OE mediates the relationship between GIC and satisfaction outcomes. This means sustainability initiatives yield their strongest results when they are internalized by employees and reflected in their workplace ties. Practical actions might include involving staff in green decision-making, celebrating shared environmental values, and encouraging collaborative sustainability projects.

Finally, the moderated-mediation effect of TAW shows that the strength of the indirect effect of GIC on CS and LS via OE is amplified when employees are high in vitality and learning. In practice, managers should focus on cultivating thriving conditions by providing stimulating roles, opportunities for growth, and psychological safety. Employees who thrive are better equipped to absorb and respond to sustainability-oriented efforts, maximizing the impact of GIC across employee engagement and behavioral domains.

In conclusion, sustainability-oriented strategies like GIC, when matched with thriving employees, can create a powerful system for engagement and satisfaction. Hospitality firms that embed green values into their human resource systems and foster personal vitality are likely to outperform in terms of retention, loyalty, and service excellence.

5.4. Limitations and Future Recommendations

This study offers valuable contributions; however, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations. The research was conducted exclusively within Turkey’s hospitality sector, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other cultural or industry settings. Future studies should explore these dynamics across diverse geographic and sectoral contexts.

Additionally, a limitation related to the heterogeneity of roles among hotel employees can be noted. While the study included both frontline and back-office staff, the lack of subgroup analysis may have obscured role-specific dynamics in how GIC is perceived and experienced.

A second limitation involves the use of a cross-sectional research design, which limits the ability to draw causal inferences. Longitudinal approaches could help illuminate the evolving impact of GIC on OE and employee satisfaction over time.

In addition, potential non-response bias may affect the generalizability of our results. Although participation was voluntary and anonymity was guaranteed, it is possible that employees who were more engaged with environmental issues were more likely to participate, which may limit representativeness. Future studies could apply longitudinal or multi-source data collection methods to reduce these risks and enhance validity.

Additionally, although GIC is conceptually composed of human, structural, and relational capital dimensions, it was modeled as a unidimensional construct in this study. This decision was supported by factor analysis results showing high internal consistency and adequate model fit. However, this approach may limit the exploration of unique effects across the subdimensions. Future research is encouraged to examine GIC components separately to gain deeper insights into how each dimension influences employee and organizational outcomes.

Finally, although TAW was examined as a moderator in this study, other variables such as leadership style, job autonomy, or organizational culture may also play influential roles. Future research should investigate additional mediating and moderating mechanisms to gain a more holistic understanding of how sustainability-oriented practices shape employee behavior and perceptions.

Addressing these limitations will allow future research to deepen theoretical frameworks and offer richer insights into the intersection of sustainability, employee well-being, and organizational dynamics both within and beyond the hospitality industry.

In conclusion, this study enhances the understanding of how GIC operates as a strategic resource that positively influences employee outcomes such as career satisfaction and life satisfaction. By establishing OE as a key mediator, the research shows how sustainability-oriented values and resources can strengthen employees’ connection with their organization, leading to more meaningful work experiences.

Furthermore, the moderating role of TAW highlights that employees with higher levels of vitality and learning orientation are better positioned to internalize green values and reflect them in their work attitudes and behaviors.

From a practical perspective, the findings suggest that by integrating GIC into their organizational culture and supporting a climate where employees thrive, hospitality firms can reinforce workforce stability, increase satisfaction, and align their people practices with long-term sustainability objectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G. and G.K.; Methodology, E.G. and G.K.; Formal analysis, E.G.; Investigation, E.G.; Data curation, E.G.; Writing—original draft, E.G.; Writing—review & editing, G.K.; Supervision, G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee of Cyprus International University (protocol code EKK21-22/012/01 and date of approval: 4 April 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available; however, they can be provided by the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Karatepe, O.M.; Çolakoğlu, Ü.; Yurcu, G.; Kaya, Ş. Do financial anxiety and generalized anxiety mediate the effect of perceived organizational support on service employees’ career commitment. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 36, 1087–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Manuel, R.S.; Borges, N.J.; Bott, E.M. Calling, vocational development, and well being: A longitudinal study of medical students. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Saydam, M.B.; Okumus, F. COVID-19, mental health problems, and their detrimental effects on hotel employees’ propensity to be late for work, absenteeism, and life satisfaction. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 934–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanyasak, T.; Koseoglu, M.A.; King, B.; Aladag, O.F. Business model adaptation as a strategic response to crises: Navigating the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2022, 8, 616–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, T.; Hai, N.T.T. Hospitality, tourism, human rights and the impact of COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2397–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.J.; Choi, Y. Korea’s Economic Policy Changes: Reflected in the Corporate Financial Indicators During the Last 60 Years. Bank of Korea WP. 2023, 14. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4526236 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Jung, H.S.; Jung, Y.S.; Yoon, H.H. COVID-19: The effects of job insecurity on the job engagement and turnover intent of deluxe hotel employees and the moderating role of generational characteristics. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahafzah, A.G.; Aljawarneh, N.M.; Alomari, K.A.K.; Altahat, S.; Alomari, Z.S. Impact of customer relationship management on food and beverage service quality: The mediating role of employees satisfaction. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2020, 8, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. The positive effect of green intellectual capital on competitive advantages of firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 77, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, Y.M.; Omar, M.K.; Kamarul Zaman, M.D.; Samad, S. Do all elements of green intellectual capital contribute toward business sustainability? Evidence from the Malaysian context using the partial least squares method. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Parasuraman, S.; Wormley, W.M. Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.D.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.; Gogia, E.H.; Shao, Z.; Rehman, M.Z.; Ullah, A. The impact of green HRM practices on green innovative work behaviour: Empirical evidence from the hospitality sector of China and Pakistan. BMC Psychol 2025, 13, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oubibi, M.; Fute, A.; Xiao, W.; Sun, B.; Zhou, Y. Perceived Organizational Support and Career Satisfaction among Chinese Teachers: The Mediation Effects of Job Crafting and Work Engagement during COVID-19. Sustainability 2022, 14, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y. The interplay of job embeddedness, collective efficacy, and work meaningfulness on teacher well-being: A mixed-methods study with digital ethnography in China. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1448446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampofo, E.T.; Karatepe, O.M. The effects of on-the-job embeddedness and its sub-dimensions on small-sized hotel employees’ organizational commitment, work engagement and turnover intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.; Sutcliffe, K.; Dutton, J.; Sonenshein, S.; Grant, A.M. A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.R.; Holtom, B.C.; Lee, T.W.; Sablynski, C.J.; Erez, M. Why people stay: Using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1102–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.; Spreitzer, G.; Gibson, C.; Garnett, F.G. Thriving at work: Toward its measurement, construct validation, and theoretical refinement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 250–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.W.; Karatepe, O.M.; Rescalvo-Martin, E.; Rizwan, M. Thriving at work as a mediator between high-performance human resource practices and innovative behavior in the hotel industry: The moderating role of self-enhancement motive. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 123, 103897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusliza, M.-Y.; Yong, J.Y.; Tanveer, M.I.; Ramayah, T.; Noor Faezah, J.; Muhammad, Z. A structural model of the impact of Green Intellectual Capital on Sustainable Performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: The role of psychological green climate and employee green values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.M.M.; Ahmed, U.; Ismail, A.I.; Mozammel, S. Going intellectually green: Exploring the nexus between green intellectual capital, environmental responsibility, and environmental concern towards environmental performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelmaged, M.; Hashem, G. Absorptive capacity and green innovation adoption in SMEs: The mediating effects of sustainable organisational capabilities. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Demir, E. Linking core self-evaluations and work engagement to work-family facilitation: A study in the hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 26, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheewaprapanan, A.; Punyasiri, S. The Causal Effects of Leader-Member Exchange on Job Embeddedness towards Enhancing Creative Performance in the Hotel Industry. Suranaree J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 18, e268983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, N.S.; Azad, F.T.; Ganjouie, A.A.; Kooshan, Z.; Rastegar, R. Job Embeddedness in the Hospitality Industry: Developing a Model of Psychological Antecedents and Behavioral Consequences. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2025, 26, 160–179. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A. Universities as sustainability agents! Does green campus ensure green intellectual capital? A quantitative approach to the triggering role of green knowledge sharing and green innovation. J. Intellect. Cap. 2025, 26, 253–278. [Google Scholar]

- Arici, H.E.; Cakmakoglu Arıcı, N.; Altinay, L. The use of big data analytics to discover customers’ perceptions of and satisfaction with green hotel service quality. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wu, T.J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y. A systematic review of thriving at work: A bibliometric analysis and organizational research agenda. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2024, 62, 507–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wu, J.; Wan, P. Linking social-related enterprise social media usage and thriving at work: The role of job autonomy and psychological detachment. Kybernetes 2025, 54, 678–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyensare, M.A.; Jain, P.; Asante, E.A.; Adomako, S.; Ofori, K.S.; Hayford, Y. Fostering assigned expatriates’ thriving at work through cultural intelligence and local embeddedness: The role of relational attachment. J. Int. Manag. 2025, 31, 101222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.C.; Chih, C.; Liu, C.H.; Ko, W.H. How Does Psychosocial Safety Climate Address Hotel employees’ Job Embeddedness and Organizational Commitment During Crisis? J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2024; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Reciprocal relationships between job resources, personal resources, and work engagement. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.H.; Naseem, M.A.; Battisti, E.; Alfiero, S. The effect of green intellectual capital and innovative work behavior on green process innovation performance in the hospitality industry. J. Intellect. Cap. 2024, 25, 402–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Karadas, G. Do psychological capital and work engagement foster frontline employees’ satisfaction? A study in the hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1254–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shazali, A.M.; Zainudin, N.F.S.; Mohamed, Z.; Hussin, N. Green intellectual capital measurement in the hotel industry: The developing country study. Corp. Gov. Organ. Behav. Rev. 2023, 7, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanusi, F.A.; Johl, S.K. Sustainable internal corporate social responsibility and solving the puzzles of performance sustainability among medium size manufacturing companies: An empirical approach. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, C.D.; Bennett, R.J.; Jex, S.M.; Burnfield, J.L. Development of a global measure of job embeddedness and integration into a traditional model of voluntary turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfreda, A.; Kulichyova, A.; Ting, A. “Thriving at work” in tourism and hospitality: An integrative systematic literature review and research agenda. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.H.; Malik, S.A. Driving firm performance with green intellectual capital: The key role of business sustainability in SMEs. Journal of Intellectual Capital. J. Intellect. Cap. 2025, 26, 691–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.-Y.; Hsu, C.-T.; Chiang, H.-C. How does green intellectual capital influence employee pro-environmental behavior? The mediating role of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 28, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslamlou, A.; Karatepe, O.M.; Uner, M.M. Does job embeddedness mediate the effect of resilience on cabin attendants’ career satisfaction and creative performance? Sustainability 2021, 13, 5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jermsittiparsert, K. The Moderation Effect of Supply Chain Information Technology Capabilities on the Relationship between Customer Relationship Management with Organizational Performance of Thai Restaurants and Hotels. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th International Conference on E-Education, E-Business, E-Management, and E-Learning, Osaka, Japan, 10–12 January 2020; pp. 338–346. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyar, M.N.; Ali, F.; Shafique, I. Green mindfulness and green creativity nexus in hospitality industry: Examining the effects of green process engagement and CSR. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 2653–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Brío, J.Á.; Fernández, E.; Junquera, B. Management and employee involvement in achieving an environmental action-based competitive advantage: An empirical study. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 491–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmansyah, D.; Purwoko, B.; Gustari, I.; Dinarjito, A. The role of green intellectual capital and employee innovativeness in enhancing job and financial performance: Insights from Indonesia’s state-owned enterprises. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2025, 4, 573–588. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Lee, A.; Han, H.; Kim, H.R. Organizational justice and performance of hotel enterprises: Impact of job embeddedness. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 21, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechawatanapaisal, D. The mediating role of organizational embeddedness on the relationship between quality of work life and turnover: Perspectives from healthcare professionals. Int. J. Manpow. 2017, 38, 696–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slatten, T.; Mutonyi, B.R.; Lien, G. Why should we strive to let them thrive? Exploring the links between homecare professionals thriving at work, employee ambidexterity, and innovative behavior. BMC Nursing 2025, 24, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.F. Recognising deductive processes in qualitative research. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2000, 3, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R.W. Convenience sampling, random sampling, and snowball sampling: How does sampling affect the validity of research? J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 2015, 109, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill-Building Approach, 7th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 5th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alothmany, R.; Jiang, Z.; Manoharan, A. Linking high-performance work systems to affective commitment, job satisfaction, and career satisfaction: Thriving as a mediator and wasta as a moderator. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 34, 3787–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Im, J.; Shin, Y.H. Relational resources for promoting restaurant employees’ thriving at work. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 3434–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Tourism Statistics; Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Culture and Tourism: Ankara, Turkey, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 587–632. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. (IJeC) 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).