1. Introduction

The adult population of rural Alaska include the core fisheries and those who rely on the ocean for food, subsistence, and industrial income. Their knowledge about the changing ocean is a critical factor that will impact the future sustainability of these fisheries. Without focusing on the learning experience of those people whose participation in the blue economy, for subsistence and employment, the outcomes of current research into the decline of marine resources will continue. An educated working population able to grapple with the coming changes to our marine resources is essential to their sustainability. It is these industrial practices that are directly responsible for overfishing, by-catch that reduces diversity, and other core factors identified as threats to biodiversity.

Alaska’s 10,600 km coast is a critical example of a marine stewardship challenge that requires careful management in the face of a rapidly changing climate. Alaska’s unique conditions have resulted in coastal areas warming nearly four times faster than other parts of the world [

1]. While the landmass of Alaska is substantial, the vast majority of people live along the coast and, like the marine life of the region, rely heavily on healthy oceans. These oceans are already experiencing the impacts of sea level rise, ice loss, ecosystem shifts, ocean acidification, novel disease manifestations, and unusual weather events [

2] along with radical changes to the wildlife that threaten the food systems on which the economy depends [

3].

Alaska’s coastal rural populations have persisted for more than 7500 years, with most continuing to rely on subsistence practices integrated with their historic marine ecosystems. These communities draw on traditional ecological knowledge while adopting new commercial technologies and data systems that have emerged in an era defined by internet connectivity and an information economy. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game [

4] has estimated the annual wildlife harvest at 36.9 million pounds of wild foods, with fish comprising the largest component and marine mammals representing approximately 14% of subsistence harvests.

For Indigenous communities, whaling and marine mammal hunting persist as fundamental components of cultural identity [

5]. These remote communities operate dual economies where subsistence practices intersect with commercial fishing within regulatory frameworks where conflicts between federal and state regulations require constant negotiation [

6]. For example, longitudinal anthropological studies have documented how climate change is reshaping traditional hunting and whaling practices including how changes in sea ice conditions, species distribution, and migratory timing have made marine mammal hunting increasingly dangerous or inaccessible for Alaska Native communities, particularly in regions where thinning ice impedes travel and safety [

7]. Political analysis has demonstrated that federal regulatory regimes and exclusion from participation in policy, combined with a lack of participation in scientific priority setting, has further disrupted Indigenous food sovereignty while weakening tribal access to traditional food sources [

8]. While these practices represent one of North America’s last functioning subsistence economies, the rapid pace of environmental change is disrupting the knowledge systems on which these communities depend. Therefore, the adult education of rural Alaskan’s is a socio-economic topic that is particularly relevant to advancing sustainable practices to protect these resources.

This marine socio-ecological system is essential to the future of coastal peoples, their role in Alaska’s cultural and economic landscape, and their contribution to global food webs. Given the mounting pressures of climate change on economies already struggling with complex regulatory regimes, the intersection of traditional ecological knowledge and Western scientific research practices become increasingly critical in the face of a changing climate [

6]. These critical issues suggest that rural village residents cannot rely solely on traditional formal education to adapt to rapid contemporary changes. Instead, they must increasingly depend on informal learning systems that integrate both indigenous knowledge and formal scientific research traditions—both essential for ensuring community persistence and adaptation during this era of unprecedented environmental and economic transformation.

Building on this foundation, the present study had three primary objectives: (1) to describe Alaska’s informal marine science learning ecosystems, (2) to analyze the marine science and ecological research outputs in the literature to describe the valence of research as indicators of political priorities in relation to Alaska’s marine economy, and (3) to synthesize these findings within the context of Alaska’s socio-political climate to evaluate gaps and inform priority setting for informal marine science learning that can meet the needs of communities most reliant on these marine resources.

We employed systematic data collection, GIS mapping to visualize the data using open-source data [

9], and a comparative analysis of the investments and distribution of marine science and the informal marine science learning ecosystem. Our methods involved cataloging institutions, programs, and peer-reviewed publications, followed by a geospatial analysis to reveal regional disparities in access and thematic coverage. The regional heat maps and comparative charts produced for our analysis illustrated structural imbalances in resource distribution, infrastructure gaps, and research concentration patterns.

The first portion of the study evaluates the types of institutions engaged in public science and public science learning, the topical focus of research efforts, and the availability of educational opportunities through colleges, libraries, informal science learning centers, tribal organizations, and distance learning support programs. These visualizations reveal where scientific engagement opportunities align with local ecological priorities—and where gaps exist between research efforts and the community-based venues needed to make that research meaningful, especially in rural areas.

This study excludes the K–12 public education curriculum because state science standards, while establishing baseline marine science knowledge, offer only a preparatory foundation for meaningful stewardship, and as noted above, is often distant from the working needs of adults reliant on the fisheries for subsistence and livelihoods. These standards prioritize generalized scientific concepts over place-based ecological wisdom, leading to curricula that often lack cultural relevance and emotional resonance. For instance, Spellman and colleagues [

10] found that youth-focused citizen science programs in Alaska were most effective when they integrated local ecological knowledge and cultural context, underscoring the limitations of standardized curricula in fostering environmental engagement. Similarly, standardized instruction that prioritizes testable content neglects experiential learning that builds emotional connection and practical conservation skills [

11]. While citizen science promises to bridge science literacy and public action—particularly when rooted in local contexts [

12], Levinson [

13] clarifies that passive data collection as a path to knowledge is limited unless it is linked to political agency in decision-making about the resources at the center of the study. It is against this background that our study focused on the core informal learning systems that can support citizen agency and decision-making about resource use and resource take. It uses these data sources to consider how to advance marine stewardship and be more likely to be attributed to the informal and non-formal learning sectors of our society [

14].

To illustrate Alaska’s marine science learning landscape, we present both maps and data synthesis to clarify where investments have historically been made and where critical gaps remain. By identifying structural imbalances in how Alaskans engage with marine science, this report provides a foundation for building a more equitable, place-based scientific capacity, particularly in rural and Alaska Native communities that are often overlooked in resource planning. It highlights concerns and identifies opportunities for Alaska’s leading informal learning organizations to contribute to advancing marine ecosystem stewardship by integrating research and public learning activities using existing, redirected, or new resources.

This work contributes to a broader vision of the state’s scientific capacity that values research output, public understanding, cultural connection, and collaborative approaches to marine conservation and stewardship. It is based on the premise that co-creating with communities can increase the agency of those most impacted by a changing climate, and how the informal learning sector can represent statewide concerns about our marine ecology’s future and the centrality of Alaska Native culture and Traditional Ecological Knowledge to these systems.

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of Resources

A total of 198 organizations offering marine science education were identified and categorized by type—libraries, national parks, universities, permanent science centers, and outreach-focused nonprofits. The analysis revealed substantial disparities in access, marked by a pronounced rural–urban divide. Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Juneau hosted a concentration of resources, while smaller and more remote communities remained underserved, even in the regions where those urban centers were found. We mapped 198 organizations using a heatmap tool in QGIS 3.34 Prizren (

Figure 1) [

9].

Alaska’s informal marine science learning ecosystem spans a geographic area equivalent to 18.3% of the contiguous United States. Our assessment of 36 non-library informal marine science learning institutions reveals that most organizations operate independently, with limited staff and infrastructure, while navigating complex tensions between Eurocentric science frameworks and Indigenous knowledge systems [

16,

17].

Urban hubs such as Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Juneau host the densest concentration of institutions, including the University of Alaska’s Fairbanks and Anchorage colleges. These organizations support STEM programming and marine research, but online resources reveal few sustained informal marine science learning efforts beyond Sea Grant’s Marine Advisory Program (MAP), based at UAF. That program deploys a small number of Marine Advisory agents across vast territories to support technical assistance and education [

20]. Similarly, museum-based offerings like those at the Anchorage Museum’s Imaginarium Science Discovery Center include marine-themed content but are designed primarily to support science engagement in Anchorage, with limited mechanisms for rural outreach [

21].

In contrast to the mapping of resource distribution in

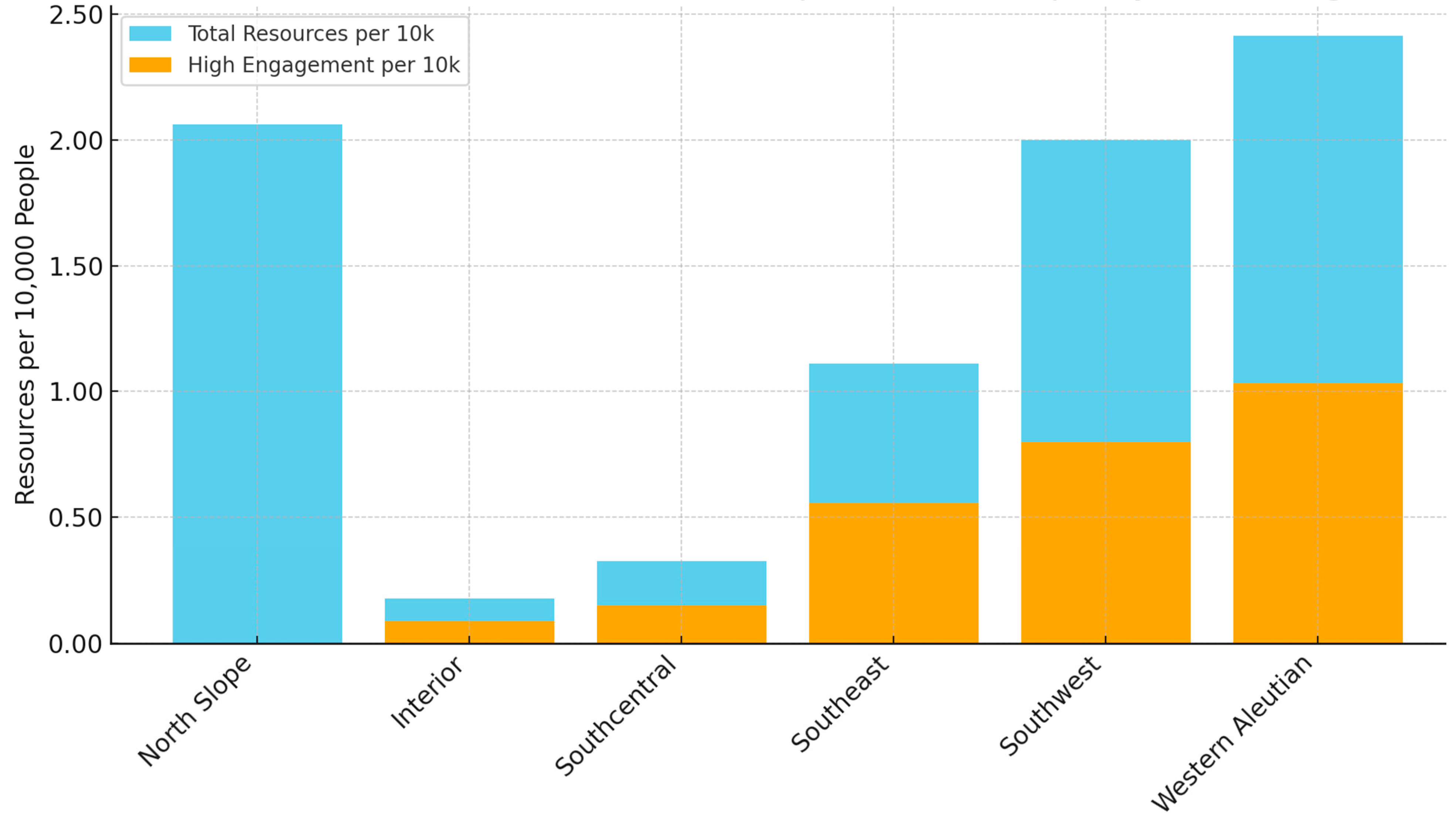

Figure 1, we illustrate below in

Figure 2 that resources per capita across the state are robust in the North Slope, but the infrequency of these engagement models across a vast area made up of very small rural villages tells a different story.

Geographic remoteness and population sparsity is a distinct state-wide challenge typified by programming in Western and Southwest Alaska. Tribal governments and community-based programs—such as the Qawalangin Tribe of Unalaska and the Aleut Community of St. Paul Island—play central roles in marine education and environmental monitoring. Initiatives like “Dockside Discovery” and “Ocean Day” provide hands-on learning in local contexts but are heavily reliant on intermittent grants and individual staff supported by the UAF SeaGrant team [

20,

21]. Likewise, Salmon Camp, coordinated by the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge, has long engaged youth across Kodiak Island, but as of spring 2025, its website had removed all past reports and event listings, raising concerns about loss of these resources [

22].

Southcentral Alaska has seen a small number of organizations—such as the Alaska SeaLife Center, the Prince William Sound Science Center, the Center for Alaskan Coastal Studies, the Chugach Regional Resource Commission, the Alutiiq Museum and Archeological Repository, and SeaGrant—begin to coordinate efforts across the

Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Impacted Zone [

23]. This collaborative framework, developed in partnership with two Alaska Native–led organizations and the Alaska Sea Grant, is the region’s first attempt at strategic alignment. Yet these institutions continue to report limitations tied to staff capacity, seasonality, and large geographic coverage areas.

In Southeast Alaska, organizations like the Sitka Sound Science Center and University of Alaska Southeast operate placed-based learning centers, school programs, and science festivals such as the Sitka WhaleFest. These programs have strong local identities but are largely confined to their urban audiences in Sitka and Juneau [

24].

The Interior region lacks direct marine access and the North Slope’s limited populations both rely almost exclusively on traveling programs or virtual outreach with a few noted exceptions. Iḷisaġvik College in Utqiaġvik has developed community science workshops incorporating marine subsistence knowledge and Iñupiaq culture. However, its reach remains localized, with scalability limited by community size and infrastructure [

25].

Alaska’s informal marine science landscape is composed of a small number of mission-driven institutions operating largely in silos. Though committed to place-based engagement, many face overlapping challenges: insufficient staffing, limited opportunities to collaborate on state-wide priority issues, fragmented delivery models, vulnerability to funding cycles, and a persistent difficulty in integrating Indigenous and Western epistemologies.

3.2. Internet Access and Educational Equity

Alaska’s digital divide exacerbates inequitable access to science learning, particularly for residents in rural and remote regions. According to BroadbandNow [

26], 21% of residents statewide do not have access to a wired or fixed wireless broadband offering of at least 25 Mbps download speed. Moreover, 60% of residents are unable to access broadband for

$60/month or less, making cost a prohibitive factor even in areas where connectivity exists.

This limited connectivity constrains participation in virtual marine science programs, online citizen science platforms, and access to digital environmental data. For instance, educators in places like Bethel or Dillingham may be unable to stream video content or join statewide professional development webinars offered by institutions like the Alaska SeaLife Center or the Prince William Sound Science Center. Youth in broadband-deficient areas also lack equitable opportunities to engage in virtual internships, remote field camps, or web-based citizen science like seabird monitoring or coastal debris tracking.

Even basic access to state-supported databases like the Statewide Library Electronic Doorway (SLED) is uneven, despite its potential to bridge knowledge gaps. Libraries and schools serving subsistence communities often rely on shared satellite connections with limited bandwidth, restricting their ability to download scientific documents, access real-time ocean data, or participate in webinars and video conferencing.

The compounded impact of geography, infrastructure, and cost underscores the critical role of offline and analog resources (e.g., printed materials and in-person visits) in advancing marine science literacy in Alaska’s most isolated regions. Besides barriers to accessing digital science resources in rural Alaska, it is critical to embed digital equity solutions into any statewide marine education strategy.

3.3. Library Infrastructure and per Capita Access

Libraries were analyzed for urban/rural distribution and per capita access, revealing a distinct pattern of structural reliance on small, decentralized facilities in rural Alaska. While rural Alaskans benefit from significantly higher library density per capita—0.32 libraries per 1000 people compared to 0.08 per 1000 in urban areas—this apparent advantage masks underlying disparities in service capacity, staffing, and programming. For example, while

Figure 3 suggests that library presence is substantial for rural communities, what constitutes a library in that matrix may be as simple as a reading room with a computer, shared materials stored in a community building, and a local volunteer supporting resource access.

Urban libraries, such as those in Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Juneau, are typically funded through municipal tax bases, supplemented by dedicated library district resources, state and federal funds, allowing for robust staffing models and access to professional development. These libraries routinely support STEM programs, author talks, curated exhibits, and seasonal events with marine and environmental science themes. In contrast, most rural libraries in Alaska operate on annual budgets ranging from

$20,000 to

$45,000 (

Table 1) with much of this funding dependent on fluctuating state-level or state pass-through federal grants. Contemporaneously with writing this article, Alaska libraries had already experienced a nearly 75% state funding cut in 2024, followed by the loss of approximately

$900,000 of the

$1.2 million in federal funding for Alaska’s libraries [

27].

For example, the Tok Community Library in the Interior region operates on an annual budget of roughly

$20,000, with the Alaska Public Library Assistance (PLA) grant comprising a major portion [

28]. In Southcentral Alaska, the Ninilchik Community Library operates with a modest

$30,000–

$40,000 annual budget [

29]. These limited budgets often cover all operations—including staffing, materials acquisition, internet access, and building maintenance—making it difficult to support specialized science content or staff training. Both of those libraries may need to substantially curtail their work.

Staffing challenges in rural Alaska libraries are intensified by the absence of in-state graduate library science programs, forcing these institutions to depend on part-time staff or volunteers who lack formal training in collection management, information literacy, or science communication. Professional development remains largely inaccessible due to prohibitive costs and geographic isolation—many libraries must close entirely when staff travel for training, temporarily cutting off community access to essential services.

While Alaska’s library infrastructure appears robust on paper, rural libraries operate with insufficient staff, funding, and marine science programming that maps to community need. Despite these constraints, rural libraries and their volunteer supporters can serve as essential community hubs for information access and lifelong learning, particularly in areas lacking schools, museums, or reliable broadband infrastructure. In many communities, the library functions as the only public institution maintaining regular hours where residents can access books, search databases, and use online resources. This positions rural libraries as critical infrastructure for informal marine science education, especially when supported through external partnerships and centralized content delivery from established learning institutions. Strengthening rural library participation in marine literacy initiatives will require targeted investment in staff training, adaptable science education resources, digital infrastructure support, and regional networks connecting library personnel with scientists, educators, and resource organizations.

3.4. Educational Attainment and Income

Rural regions report lower educational attainment and income, with just 17% of adults holding bachelor’s degrees in the Interior, Southwest, and Far North regions. These areas also reported median incomes of around

$30,532, in contrast to higher attainment and income in Southcentral and Southeast, where the median household income approaches

$50,000 and college attainment is closer to 25–30% [

30].

However, average income alone is a limited and potentially misleading proxy for access to knowledge and engagement in science in rural Alaska. Many rural and Alaska Native communities operate within subsistence-based economies, where hunting, fishing, and foraging replace income-based consumption. The high reliance on Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and intergenerational learning practices often occurs outside of formal education systems or monetary economies.

Scientific resources—particularly those derived from Eurocentric paradigms and disseminated in technical formats—may be culturally unfamiliar, linguistically inaccessible, or thematically misaligned with locally held values and understandings. TEK frameworks, grounded in long-term observation, reciprocity, and community practice, do not map cleanly onto linear, data-driven formats of environmental science, which may emphasize reductionist models over holistic interdependence.

As a result, even when scientific resources are technically available—through databases, PDFs, or online portals—they may not be readily interpretable or perceived as relevant to local concerns. This creates a compounded disparity for communities that are not only geographically remote and digitally underserved but also epistemologically excluded from dominant science communication norms.

The combination of lower educational attainment, subsistence economies, and TEK-based systems suggests the need for culturally anchored, translational approaches. Rural libraries, tribal offices, and local educators must be equipped not only with scientific content but with interpretive frameworks, metaphors, and delivery formats that resonate with lived experience. Marine science education in these regions must prioritize relationships, place-based stories, and dialogic approaches to connect scientific insights with the priorities of communities who are on the frontlines of a regenerative ecology. Without such translation, the benefits of emerging marine science research will continue to bypass the very communities whose stewardship is critical to Alaska’s marine future.

3.5. Marine Science Research Trends

In parallel to the study of the informal learning infrastructure, the second aspect of this study undertook a configurative review of 9549 peer-reviewed articles to assess the thematic and regional focus of marine science in Alaska. Publications were drawn from Web of Science and Google Scholar, spanning 1989 to early 2024. Articles were screened by two researchers and organized into three primary marine regions—the Gulf of Alaska, Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands, and Arctic Ocean—and three trophic categories: marine mammals, seabirds, and “fishes” including fish habitats, shellfish, and tidepool animals.

The distribution of publications illustrated in

Figure 4 revealed a strong emphasis toward marine mammal research. Marine mammals were the most frequently studied group in all three regions, accounting for over 45% of publications analyzed. “Fish” followed at 38%, while seabirds represented only 17% of the total research output.

As

Figure 5 illustrates, the Gulf of Alaska region, which was most impacted by the

Exxon Valdez Oil Spill, had the highest number of publications per species, driven in part by access to research infrastructure, long-standing institutional presence (e.g., UAF, NOAA Auke Bay), and the presence of well-monitored fisheries. The Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands—despite their ecological richness and importance to subsistence economies—had the lowest publication-to-species ratio. For example, Arctic char and Dolly Varden, which are central to rural and Indigenous subsistence practices, were notably underrepresented in the literature compared to more commercially prominent species such as salmonids. Specific shellfish and other tidepool animals represented under 20 papers across the “fishes” category.

The most underrepresented category across all regions was seabirds. Iconic or culturally significant species like the Kittiwakes, Murres, and Auklets—integral to subsistence harvests in Western Alaska and the Arctic—received comparatively little research attention. In the Arctic Ocean region, for instance, some seabird species had fewer than 10 peer-reviewed articles over a 35-year period. This absence is particularly concerning given the role these species play in both ecological monitoring and Indigenous diets, where they serve as early indicators of ecosystem change and contribute to seasonal food security.

This disparity reflects not only the logistical challenges of conducting research in remote regions but also the systemic biases in funding and scientific prioritization. Marine mammals often attract greater public and institutional interest due to their charismatic appeal and alignment with conservation branding. However, such focus can eclipse species that are of greater direct relevance to Indigenous communities and subsistence users.

The underrepresentation of subsistence-critical species, particularly seabirds and tidepool animals, signals a misalignment between Western science priorities and community-based needs in Alaska. When combined with the barriers outlined in

Section 3.4—including limited broadband, lower formal education levels, and culturally divergent knowledge systems—this research imbalance perpetuates a system in which communities most dependent on marine systems are the least informed by or engaged with the science shaping resource decisions.

This finding highlights an opportunity for informal learning institutions to reorient research priorities toward trophic and regional gaps that matter most to Alaska’s rural and Indigenous communities. In doing so, this new focus can expand focus on seabird ecology in ways that integrate TEK perspectives, knowledges, and community-driven research agendas to ensure that science becomes a shared resource in the pursuit of regenerative marine stewardship.

This disparity in attention reflects both logistical barriers and systemic research priorities that may undervalue trophic levels or species groups with less commercial or charismatic appeal. It also indicates opportunities for informal STEM and cultural learning groups to strategically invest in seabird-focused research, Bering Sea basin ecological monitoring, and expanded engagement with Indigenous co-researchers to contextualize findings within lived experience.

4. Discussion Bridging the Research–Practice Divide in Marine Stewardship

The findings from this study highlight a persistent and troubling gap between the production of knowledge through marine science research and its accessibility or relevance to coastal communities through the informal learning infrastructure. This gap is especially pronounced in the most rural areas where Alaska Native populations’ industrial and subsistence practices are closely tied to the sustainability of the marine ecosystems. For researchers and educators, the implications are profound: despite significant investments in ecological monitoring and academic research, the lack of regionally equitable, community-informed dissemination limits the practical utility of scientific findings in promoting stewardship behaviors in high-risk areas.

This disconnect reflects a structural issue in how marine science knowledge is produced and shared. The urban concentration of institutions in Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Juneau contributes to research silos that are disconnected from local knowledge systems and exclude community participation beyond those hubs. As a result, communities most dependent on healthy marine ecosystems often remain peripheral to research agendas and excluded from the benefits of that knowledge.

Historical patterns of underinvestment in science and learning infrastructure have long disadvantaged rural and Indigenous communities. As our results show, this is particularly true along the sparsely populated coasts of the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands. While this study does not assess the cultural relevance of specific solutions, it offers a descriptive account of how systemic exclusions have shaped a marine learning ecosystem that privileges centralized institutions, Western pedagogies, and urban priorities over cultural and subsistence knowledge systems that have coexisted with marine environments for millennia. Rectifying these disparities will require a shift from extractive engagement models to co-creation strategies where communities define their priorities and serve as equal partners in study design and in crafting learning experiences that support stewardship and sustainable management.

Our findings reveal that fragmentation among informal science institutions and competition for limited resources hinder statewide collaboration. While we avoided political conjecture and species-specific prioritization, the absence of culturally and ecologically significant species such as bidarki, a tidepool species threatened by toxic algae that is being actively studied by our colleagues at Alutiiq Pride, demonstrates how scientific visibility is unevenly distributed [

31] with spare coverage of such taxa in the literature, despite their cultural and dietary significance given the now life-threatening risk of eating these once safe and delicious animals. The lack of prioritization is just one example of a broader political economy in which research funding prioritizes extractive commercial interests over long-term community relevance.

Nonprofit research organizations, regional or tribal governments, and other boundary entities are uniquely positioned to reclaim priority setting if they collaborate to overcome the historical exclusions and under-funding of infrastructure surfaced through this study. Unlike national agencies or academic institutions constrained by rigid funding mandates, disciplinary silos, or the whims of national electoral politics, state-level coordination among nonprofits and the cultural leaders across the state can promote the importance of translational agents, becoming coordinated boundary entities that support the culturally relevant integration of scientific knowledge into usable, community-centered cultural knowledge that can advance sustainability.

The near-total absence of seabird research across all regions is also emblematic of broader neglect of species central to Indigenous subsistence and ecological health. A stewardship-centered approach demands research that is both purposeful and aligned with community priorities—responsive to climate vulnerability and accessible beyond academic circles.

In practical terms, our data suggest that researchers and organizations engaged in the marine science enterprise must advocate for funding models and integrated knowledge sharing practices that reward engagement and accessibility, contribute to long-term partnerships with rural communities, and commit to open-access, plain-language communication. Marine science should be positioned not as a superior form of knowledge but as one that can complement Traditional Ecological Knowledge and the tacit knowledge held by those in Alaska’s blue economy. Doing so would enhance the relevance of marine research and empower the communities most affected by environmental change.

By drawing these inferences, we step beyond a strictly descriptive account of the interactions between Alaska’s informal science infrastructure and the research priorities evident in the published marine science literature. These reflections signal a shift in our own organizational commitments, migrating from external experts to collaborators working in partnership with other informal learning institutions, all accountable to the communities we serve. We recognize that others may draw different inferences or propose alternative strategies for achieving the sustainable management of marine systems. Nonetheless, we offer this analysis as a foundation for building more inclusive and impactful science and science learning that can lead to better a stewardship of Alaska’s marine resources.

5. Conclusions

Alaska’s informal science infrastructure and marine research landscape exhibit systemic inequities. The concentration of resources in urban centers and the disproportionate focus on marine mammals limits the broader understanding of marine ecosystems. This report demonstrates how the state’s informal learning institutions can address gaps in research, education, and public engagement through culturally grounded partnerships and place-based learning.

In doing so, we believe these data have given us an opportunity to draw a clear connection between the empirical gaps identified in the marine science literature and the institutional and political mechanisms that reproduce them as social knowledge. Our aim was not to assign blame, but rather, to illuminate opportunities for more equitable and impactful research partnerships in Alaska’s coastal and marine future.

By investing in community capacity building and embracing participatory approaches, informal learning institutions can become state-wide assets advancing marine stewardship. The integration of Western science and Indigenous knowledge, paired with equitable access to learning environments, is critical for the future resilience of Alaska’s coasts and communities.