Exploring the Impact of Virtual Reality on Tourists’ Pro-Sustainable Behaviors in Heritage Tourism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. TAM Theory

2.2. VR Tourism

2.3. Sustainable Tourism and Awe

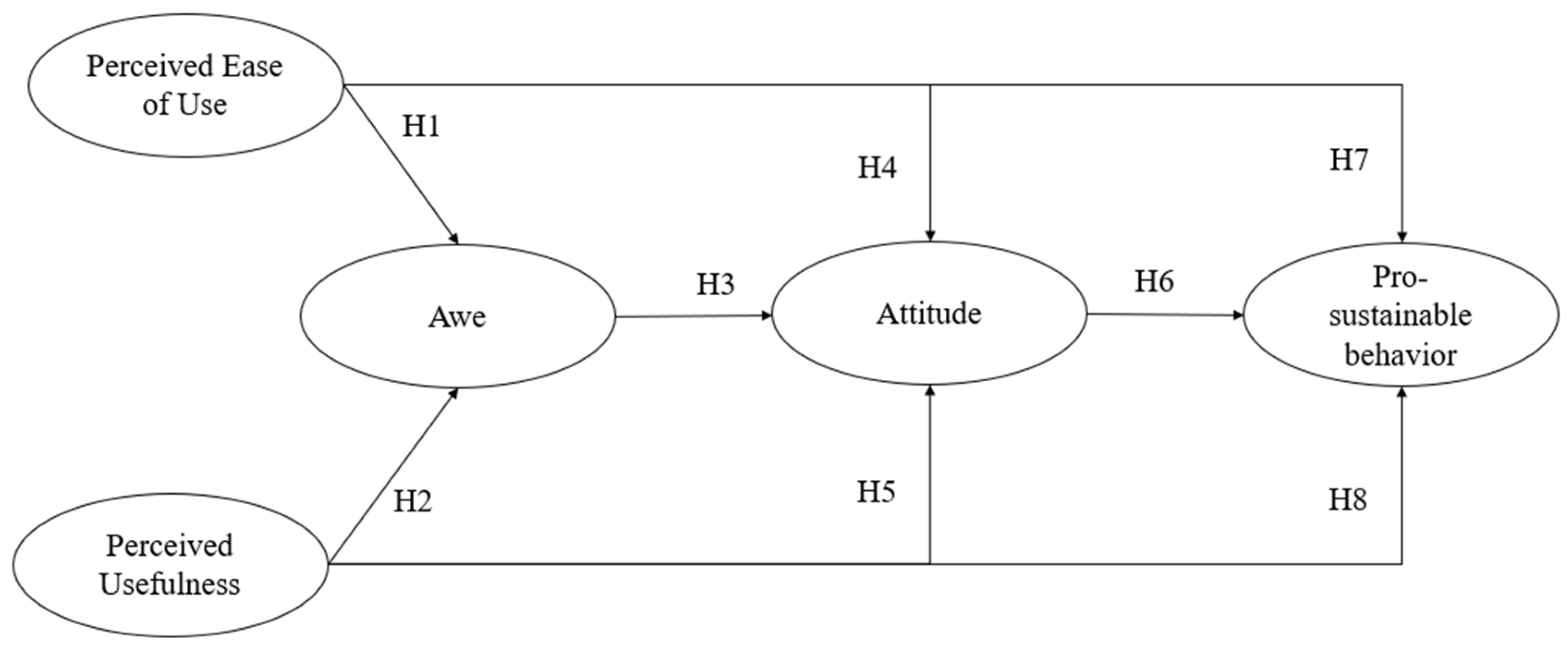

2.4. Hypothesis Development

3. Research Method

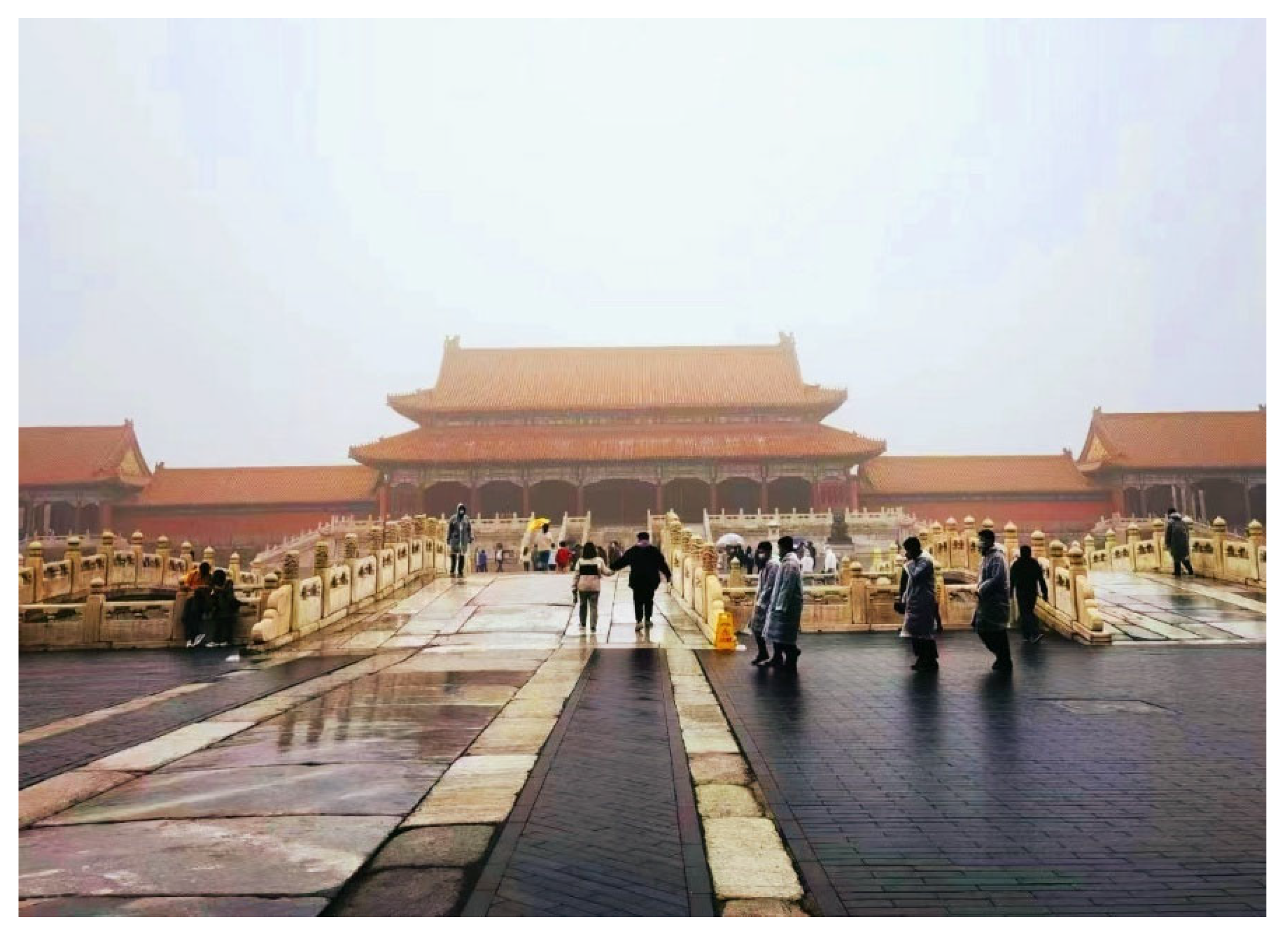

3.1. Study Site

3.2. Questionnaire Design

3.3. Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. Sample Background

4.2. Model Evaluation

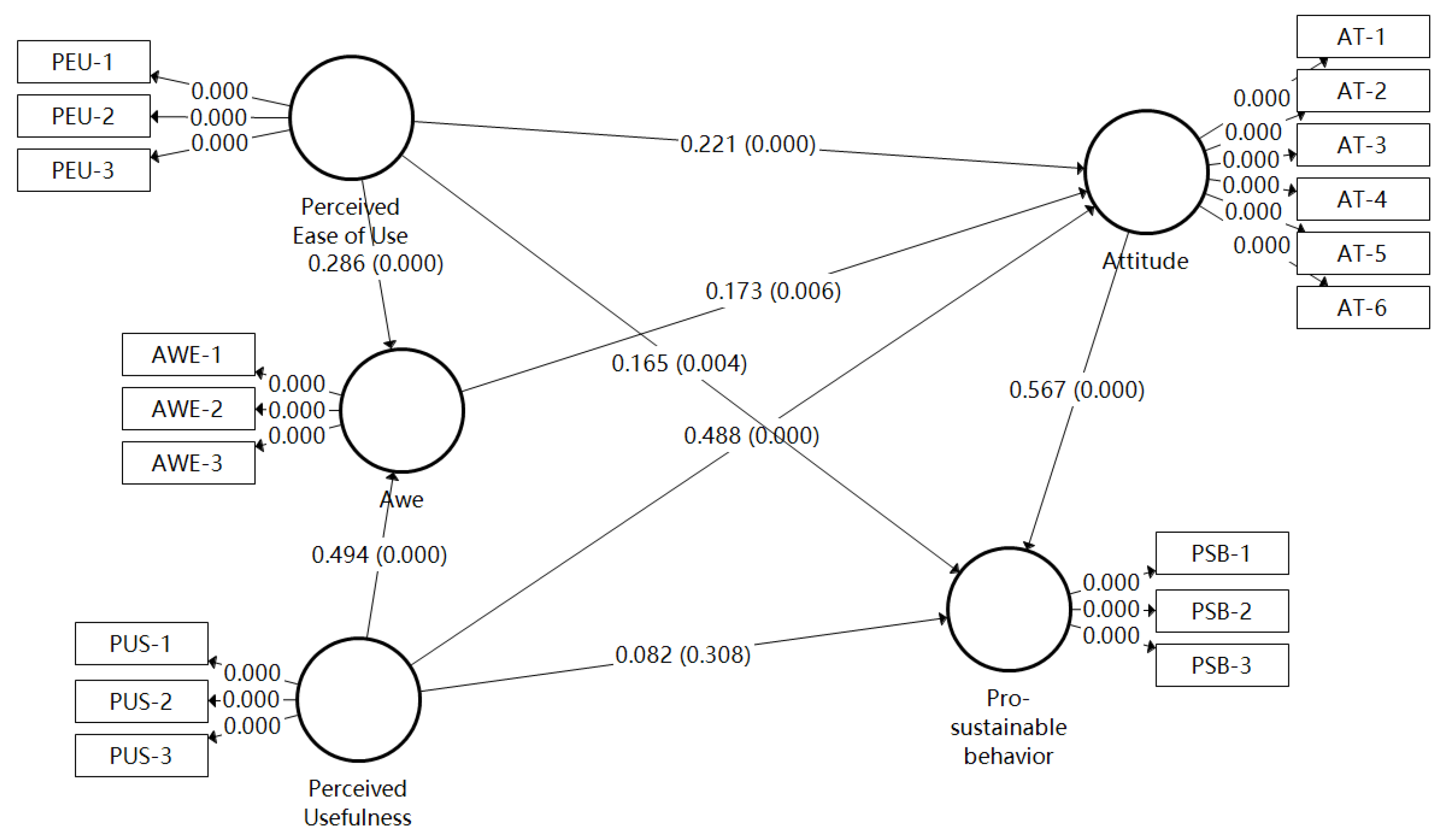

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Contributions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Melo, M.; Coelho, H.; Gonçalves, G.; Losada, N.; Jorge, F.; Teixeira, M.S.; Bessa, M. Immersive Multisensory Virtual Reality Technologies for Virtual Tourism: A Study of the User’s Sense of Presence, Satisfaction, Emotions, and Attitudes. Multimed. Syst. 2022, 28, 1027–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, N.; Jorge, F.; Teixeira, M.S.; Losada, N.; Alén, E.; Guttentag, D. Does Technological Innovativeness Influence Users’ Experiences With Virtual Reality Tourism? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.-M.; Wu, K.-S.; Kuo, F.-J. Virtual Reality Tourism: Intention to Use Mediated by Perceived Usefulness, Attitude and Desire. Tour. Rev. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.W.; Zhu, C.; Song, H.; Dempsey, I.M.B. Interpreting the Perceptions of Authenticity in Virtual Reality Tourism through Postmodernist Approach. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2022, 24, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, T.; Muldoon, M. Exploring Virtual Reality Experiences of Slum Tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2022, 24, 934–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Zou, S. An Empirical Comparison of Vignette and Virtual Reality Experiments in Tourism Research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Backman, K.F.; Backman, S.J.; Chang, L.L. Exploring the Implications of Virtual Reality Technology in Tourism Marketing: An Integrated Research Framework. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Ismail, M.; Shahruddin, S.; Quan, W.; Li, Y. Exploring Tourists’ Intentions to Adopt Augmented Reality in Cultural Heritage Museums: Insights From a Modified Technology Acceptance Model. SAGE Open 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.Z.G.; Hall, C.M.; Fong, L.H.N.; Lin, F.; Naderi Koupaei, S. Examining the Effects of ChatGPT on Tourism and Hospitality Student Responses through Integrating Technology Acceptance Model. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Han, Y.; Chen, S. Awe or Excitement? The Interaction Effects of Image Emotion and Scenic Spot Type on the Perception of Helpfulness. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 58, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Hu, Y. Nature-Inspired Awe toward Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior Intention. Tour. Rev. 2024, 79, 1000–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Jin, L.; Li, J. Impact of Awe on Sustainable Tourism Consumption Decisions: Roles of Diminished Self-Importance and Regulatory Focus. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, A.; Jia, W. The Influence of Eliciting Awe on Pro-Environmental Behavior of Tourist in Religious Tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.W.; Park, H.J.; Li, C.C.; Wang, X.R.; Chen, Y. How Awe Affects Value Co-Creation in Virtual Reality Tourism Experience. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 29, 1323–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibade, I.; Boateng, G.O. Predicting Why People Engage in Pro-Sustainable Behaviors in Portland Oregon: The Role of Environmental Self-Identity, Personal Norm, and Socio-Demographics. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 289, 112538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landon, A.C.; Woosnam, K.M.; Boley, B.B. Modeling the Psychological Antecedents to Tourists’ pro-Sustainable Behaviors: An Application of the Value-Belief-Norm Model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 957–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olya, H.; Kim, N.; Kim, M.J. Climate change and pro-sustainable behaviors: Application of nudge theory. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 1077–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiopu, A.F.; Hornoiu, R.I.; Padurean, M.A.; Nica, A.-M. Virus Tinged? Exploring the Facets of Virtual Reality Use in Tourism as a Result of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 60, 101575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho-Esper, F.; Ostrovskaya, L.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, C.; Campayo-Sanchez, F. Virtual Reality in Retirement Communities: Technology Acceptance and Tourist Destination Recommendation. J. Vacat. Mark. 2023, 29, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiopu, A.F.; Hornoiu, R.I.; Padurean, A.M.; Nica, A.-M. Constrained and Virtually Traveling? Exploring the Effect of Travel Constraints on Intention to Use Virtual Reality in Tourism. Technol. Soc. 2022, 71, 102091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Cain, L.N.; Jeon, H. Customers’ Perceptions of Hotel AI-Enabled Voice Assistants: Does Brand Matter? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 2807–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Hall, C.M. A Hedonic Motivation Model in Virtual Reality Tourism: Comparing Visitors and Non-Visitors. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 46, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soifer, I.; Berezina, K.; Ciftci, O.; Mafusalov, A. Virtual Site Visits for Meeting and Event Planning: Are US Convention Facilities Ready? J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2021, 4, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.; Rainoldi, M.; Egger, R. Virtual Reality in Tourism: A State-of-the-Art Review. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 586–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, R.; Khan, M.S.; Pasanchay, K. Virtual Reality Tourism and Technology Acceptance: A Disability Perspective. Leis. Stud. 2023, 42, 849–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttentag, D.A. Virtual Reality: Applications and Implications for Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzeni, M.; Del Chiappa, G.; Mei Pung, J. Enhancing Visit Intention in Heritage Tourism: The Role of Object-based and Existential Authenticity in Non-immersive Virtual Reality Heritage Experiences. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 24, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, N.P.; Jorgenson, J.; Boley, B.B. Are Sustainable Tourists a Higher Spending Market? Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Chee, S.Y.; Ragavan, N.A. From Mindset to Practice: How Employees’ Attitudes Impact Tourism Businesses’ Sustainability Practices. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2025, 26, 625–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Whitford, M.; Arcodia, C. Development of Intangible Cultural Heritage as a Sustainable Tourism Resource: The Intangible Cultural Heritage Practitioners’ Perspectives. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Duong, T.D.H. The Role of Nostalgic Emotion in Shaping Destination Image and Behavioral Intentions–an Empirical Study. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2025, 8, 735–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Liu, Y.; Lai, I.; Yang, L. Awe: An Important Emotional Experience in Sustainable Tourism. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaer, C.L.; Schaffer, V.; Campton, J.; Kannis-Dymand, L. Exploring the Impacts of the Soundscape, Awe and Knowledge on pro-Environmental Intent. J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 102, 102524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jia, W.; Chan, J.H.; Sciacca, A. The Awe-Habitual Model: Exploring Tourists’ pro-Environmental Behaviors in Religious Settings. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Song, M. The Influence of Tourist–Environment Fit on Environmental Responsibility Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model. Forests 2024, 15, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yuan, L.; Li, M.; Li, S.-J.; Sun, Y.; Yuan, J. Ecological Experiential Learning and Tourists’ pro-Environmental Behavior Intentions: The Mediating Roles of Awe and Nature Connection. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinero, Y.; Prayag, G.; Gómez-Rico, M.; Molina-Collado, A. Generation Z and Pro-Sustainable Tourism Behaviors: Internal and External Drivers. J. Sustain. Tour. 2025, 33, 1059–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Huang, M.; Leung, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, X. How Environmental Emotions Link to Responsible Consumption Behavior: Tourism Agenda 2030. Tour. Rev. 2023, 78, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Shang, Z.; Pan, Y. Beauty and Tourists’ Sustainable Behaviour in Rural Tourism: A Self-Transcendent Emotions Perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 32, 1413–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lu, C. The Effect of Awe in Wildlife Tourists on Animal-Friendly Behavioural Intentions: A Serial Mediation Model of Connectedness to Nature and Empathy. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 30, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.; Li, Y.; Xue, Y. Will the Interest Triggered by Virtual Reality (VR) Turn into Intention to Travel (VR vs. Corporeal)? The Moderating Effects of Customer Segmentation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiota, M.N.; Keltner, D.; Mossman, A. The Nature of Awe: Elicitors, Appraisals, and Effects on Self-Concept. Cogn. Emot. 2007, 21, 944–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawadieh, Z.; Prayag, G.; Adie, B.A.; Alrawadieh, Z. Tourism Impacts and Well-Being in Heritage Tourism: The Role of Discrete Emotions and Site Sustainability Characteristics. J. Herit. Tour. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanmardi, S.; Javanmardi, E.; Bucci, A. Quantifying Drivers of Virtual Reality Acceptance in Tourism Planning Using a Grey System Theory-Based Approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2025, 8, 1308–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, L.S.; Steppler, K.; Kliachko, I.; Kuhlmann, J.; Menzel, C.; Schick, O.; Reese, G. A Virtually-Induced Overview Effect? How Seeing the World from above through a Simulated Space Tour Is Related to Awe, Global Identity and pro-Environmental Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 99, 102428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, C.; Qian, L. Spark Aspirations: The Role of Mental Imagery and Place Memories in Virtual Communist Heritage. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2025, 62, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lai, I.K.W. How the Creativity and Authenticity of Destination Short Videos Influence Audiences’ Attitudes toward Videos and Destinations: The Mediating Role of Emotions and the Moderating Role of Parasocial Interaction with Internet Celebrities. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 2428–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.; Strickland-Munro, J.; Moore, S.A. What Fosters Awe-Inspiring Experiences in Nature-Based Tourism Destinations? J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lyu, J. Inspiring Awe Through Tourism and Its Consequence. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 77, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cui, W.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, H. Exploring Short Video Apps Users’ Travel Behavior Intention: Empirical Analysis Based on SVA-TAM Model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 912177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.; Sampat, B.; Behl, A.; Jain, K. Understanding Senior Citizens’ Intentions to Use Virtual Reality for Religious Tourism in India: A Behavioural Reasoning Theory Perspective. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2023, 48, 983–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Xiong, S. Exploring the Influence of Expectancy, Valence, and Instrumentality on VR Tourism Intention: A Framework Based on TAM and Expectancy Theory. Acta Psychol. 2024, 250, 104541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, T.; Lim, W.M.; O’Connor, P.; Ahmad, A.; Farhat, K.; De Oliveira Santini, F.; Junior Ladeira, W. Immersive Virtual Reality Experiences: Boosting Potential Visitor Engagement and Attractiveness of Natural World Heritage Sites. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 29, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omran, W.; Casais, B.; Ramos, R.F. Attributes of Virtual and Augmented Reality Tourism Mobile Applications Predicting Tourist Behavioral Engagement. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Tourism News. 74.88 Million Visits: Museums and Cultural Tourism Gain Popularity During National Day Holiday. 2024. Available online: https://www.ctnews.com.cn/jujiao/content/2024-10/10/content_165794.html (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Zhu, C.; Io, M.U.; Hall, C.M.; Ngan, H.F.B.; Peralta, R.L. Exploring the influence of augmented reality on tourist word-of-mouth through the lens of museum tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2025, 20, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zheng, J. Visiting Intentions toward Theme Parks: Do Short Video Content and Tourists’ Perceived Playfulness on TikTok Matter? Sustainability 2022, 14, 12206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, L.; Wei, L.; Su, Q. Personal and Media Factors Related to Citizens’ Pro-Environmental Behavioral Intention against Haze in China: A Moderating Analysis of TPB. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Hall, C.M.; Fong, L.H.N.; Liu, C.Y.N.; Naderi Koupaei, S. Does a Good Story Prompt Visit Intention? Evidence from the Augmented Reality Experience at a Heritage Site in China. J. Herit. Tour. 2023, 18, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM: A Full Collinearity Assessment Approach. Int. J. E-Collab. Ijec 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Frequency | Percentage |

| Male | 151 | 49.7 |

| Female | 153 | 50.3 |

| Salary monthly | ||

| CNY 4000 or CNY 4000 below | 57 | 18.8 |

| CNY 4001–6000 | 83 | 27.3 |

| CNY 6001–8000 | 51 | 16.8 |

| CNY 8001–10,000 | 53 | 17.4 |

| CNY 10,001–15,000 | 43 | 14.1 |

| Over CNY 15,000 | 17 | 5.6 |

| Education | ||

| Primary school | 1 | 0.3 |

| Middle school | 12 | 3.9 |

| Junior college | 85 | 28 |

| Undergraduate | 181 | 59.5 |

| Graduate | 25 | 8.2 |

| Age | ||

| 18–25 | 90 | 29.6 |

| 26–30 | 66 | 21.7 |

| 31–35 | 60 | 19.7 |

| 36–40 | 47 | 15.5 |

| 41–45 | 26 | 8.6 |

| 46–50 | 10 | 3.3 |

| Over 50 | 5 | 1.6 |

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) | Factor Loading |

|---|---|

| PEU1: Learning to use VR technology is easy in tourism experience. | 0.837 |

| PEU2: It is easy to navigate VR technology in tourism experience. | 0.839 |

| PEU3: The use of VR technology is flexible in tourism experience. | 0.854 |

| Perceived Usefulness (PUS) | |

| PUS-1: I think VR technology can give me a deeper understanding of products or services. | 0.893 |

| PUS-2: I think VR technology can save me time in making travel plans. | 0.814 |

| PUS-3: I think VR technology can provide me with valuable information. | 0.859 |

| AWE | |

| AWE-1: When I experienced the VR technology towards destination, what I watched gave me a deep sense of vastness. | 0.861 |

| AWE-2: When I experienced the VR technology towards destination, I felt small in front of what I watched. | 0.853 |

| AWE-3: When I experienced the VR technology towards destination, what I saw was surprising and difficult to understand. | 0.718 |

| Attitude (AT) | |

| AT-1: I think that engaging in pro-environmental behavior is enjoyable. | 0.759 |

| AT-2: I think that engaging in pro-environmental behavior is beneficial. | 0.810 |

| AT-3: I think that engaging in pro-environmental behavior is important. | 0.804 |

| AT-4: I think that engaging in pro-environmental behavior is worthwhile. | 0.826 |

| AT-5: I think that engaging in pro-environmental behavior is compatible with my lifestyle. | 0.799 |

| AT-6: I think that engaging in pro-environmental behavior is satisfying. | 0.801 |

| Pro-sustainable behavior (PSB) | |

| PSB-1: After experiencing VR technology, I perform green practices to protect the environment on my trips | 0.868 |

| PSB-2: After experiencing VR technology, I usually report to the destination administration of any environmental pollution I see when on my trips | 0.707 |

| PSB-3: After experiencing VR technology, I act responsibly to protect the destination’s environment on my trips | 0.882 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE | AT | Awe | PEU | PUS | PSB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | 0.887 | 0.914 | 0.640 | |||||

| AWE | 0.746 | 0.853 | 0.662 | 0.768 | ||||

| PEU | 0.803 | 0.881 | 0.711 | 0.741 | 0.755 | |||

| PUS | 0.817 | 0.891 | 0.732 | 0.880 | 0.849 | 0.801 | ||

| PSB | 0.762 | 0.862 | 0.677 | 0.866 | 0.834 | 0.708 | 0.766 |

| Path Coefficient | p Values | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: PEU -> Awe | 0.286 *** | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H2: PUS -> Awe | 0.494 *** | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H3: Awe -> AT | 0.173 ** | 0.006 | Accepted |

| H4: PEU -> AT | 0.221 *** | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H5: PUS -> AT | 0.488 *** | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H6: AT -> PSB | 0.567 *** | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H7: PEU -> PSB | 0.165 ** | 0.004 | Accepted |

| H8: PUS -> PSB | 0.082 ns | 0.308 | Rejected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, Z.; Hall, C.M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X. Exploring the Impact of Virtual Reality on Tourists’ Pro-Sustainable Behaviors in Heritage Tourism. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146278

Zhu Z, Hall CM, Li Y, Zhang X. Exploring the Impact of Virtual Reality on Tourists’ Pro-Sustainable Behaviors in Heritage Tourism. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146278

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Zhengan, Colin Michael Hall, Yue Li, and Xinyi Zhang. 2025. "Exploring the Impact of Virtual Reality on Tourists’ Pro-Sustainable Behaviors in Heritage Tourism" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146278

APA StyleZhu, Z., Hall, C. M., Li, Y., & Zhang, X. (2025). Exploring the Impact of Virtual Reality on Tourists’ Pro-Sustainable Behaviors in Heritage Tourism. Sustainability, 17(14), 6278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146278