A Community-Based Intervention Proposal for Municipal Solid Waste Management: Analyzing Willingness, Barriers and Spatial Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Current Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection Process

2.3. Data Analysis Process

- Note: d is the distance between the points, r is the radius of the Earth (approximately 6371 km), Δϕ is the difference in latitude between the two points, ϕ1 and ϕ2 are the latitudes of the two points (in radians), and Δλ is the difference in longitude between the two points (in radians).

3. Results

3.1. Willingness to Separate and Pro-Environmental Delivery of MSW

3.2. Perception of the MSW Problem, Barriers, and Recommendations

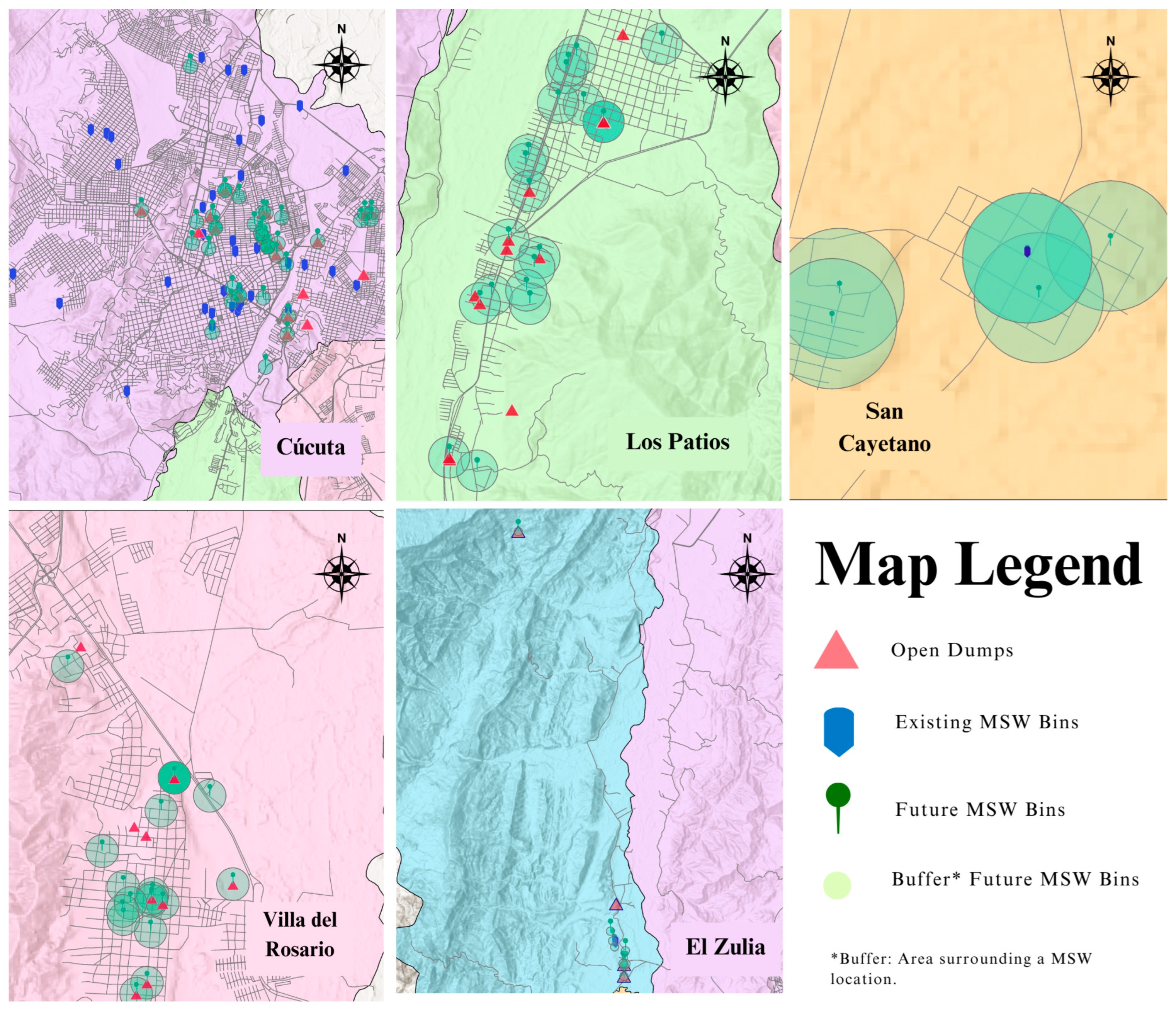

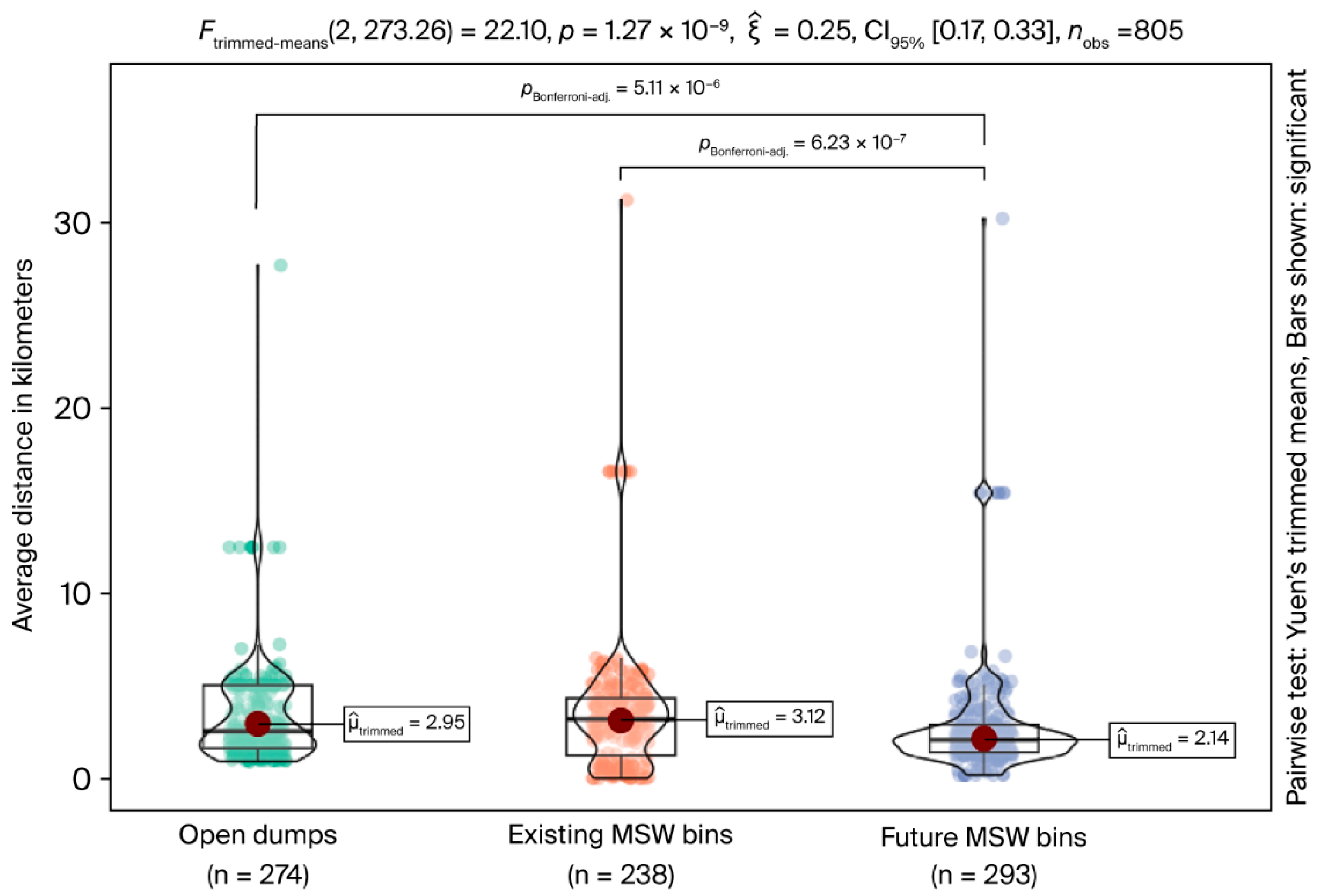

3.3. Geospatial and Distance Analysis for MSW Delivery

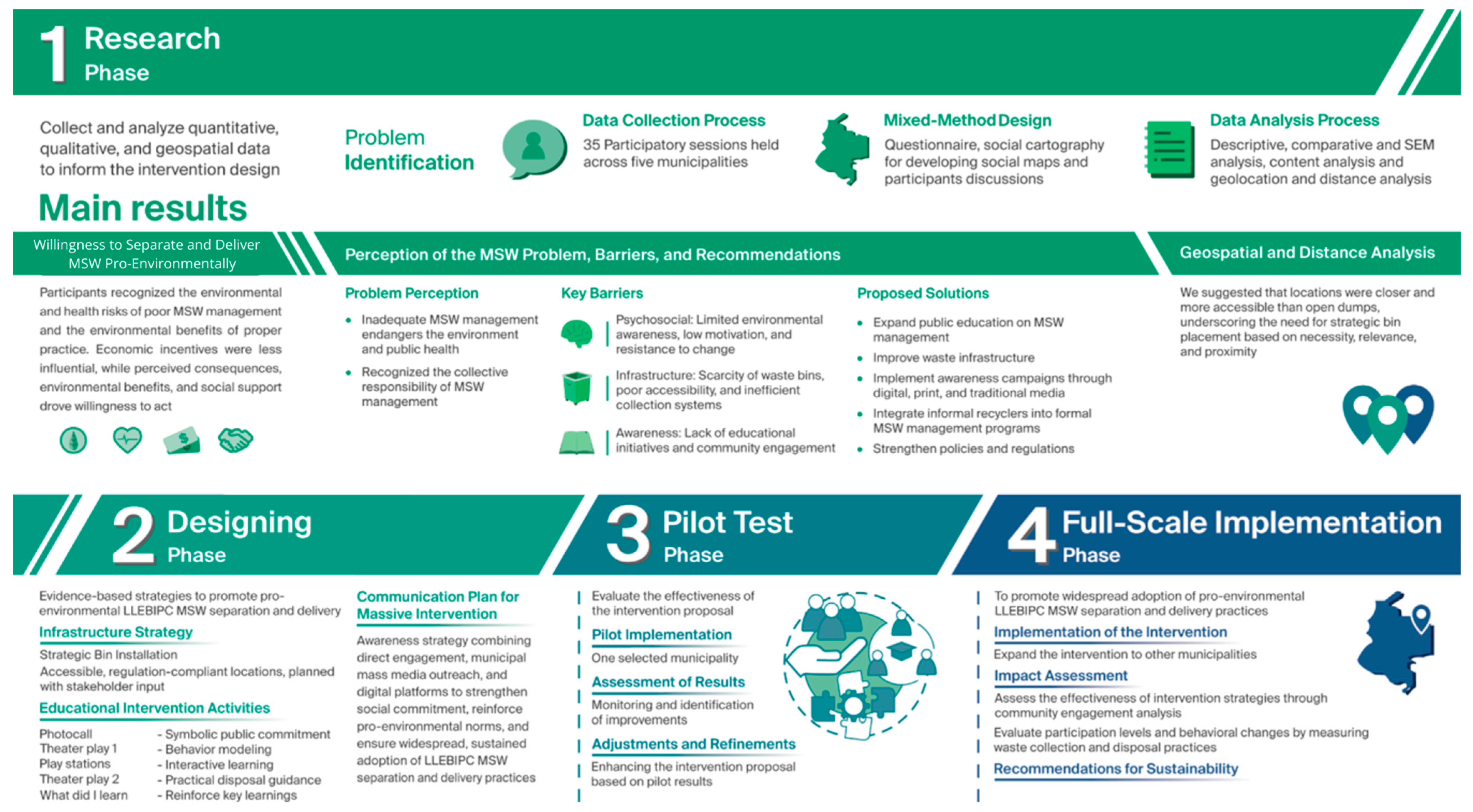

4. Intervention Proposal

5. Discussion

Study Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Transparency and Openness

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Environment Programme. Global Waste Management Outlook 2024-Beyond an Age of Waste: Turning Rubbish Into a Resource; United Nations Environment Programme: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidance on Solid Waste and Health. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/compendium-on-health-and-environment/solid-waste (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Abubakar, I.R.; Maniruzzaman, K.M.; Dano, U.L.; AlShihri, F.S.; AlShammari, M.S.; Ahmed, S.M.S.; Al-Gehlani, W.A.G.; Alrawaf, T.I. Environmental sustainability impacts of solid waste management practices in the Global South. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Yang, M.; Osman, A.I.; Farghali, M.; Liu, E.; Hassan, D.; et al. Municipal solid waste management challenges in developing regions: A comprehensive review and future perspectives for Asia and Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 930, 172794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Zuo, G. Challenges of Implementing Municipal Solid Waste Separation Policy in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. What a Waste Global Database [Metadata]. World Bank Group. 2025. Available online: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/search/dataset/0039597 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Grupo Estudios Sectoriales. Informe de Disposición Final de Residuos Sólidos 2022. 2023. Available online: https://arcg.is/1qjKKS0 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Geiger, J.; van der Werff, E.; Ünal, B.; Steg, L. Context matters: The role of perceived ease and feasibility vis-à-vis biospheric values in recycling behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2022, 16, 200122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzzo, G.; Prati, G. Psychological correlates of e-waste recycling intentions and behaviors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 204, 107462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Huda, N.; Baumber, A.; Shumon, R.; Zaman, A.; Ali, F.; Hossain, R.; Sahajwalla, V. A global review of consumer behavior towards e-waste and implications for the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, A.; Viottini, E.; Comoretto, R.I.; Piovan, C.; Martin, B.; Albanesi, B.; Clari, M.; Dimonte, V.; Campagna, S. The Effectiveness of Educational Interventions in Improving Waste Management Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices among Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, J.L.; Steg, L.; van der Werff, E.; Ünal, A.B. A meta-analysis of factors related to recycling. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 64, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trushna, T.; Krishnan, K.; Soni, R.; Singh, S.; Kalyanasundaram, M.; Sidney Annerstedt, K.; Pathak, A.; Purohit, M.; Stålsby Lundborg, C.; Sabde, Y.; et al. Interventions to promote household waste segregation: A systematic review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Z.; Gu, Y.; Li, J.; Xie, J.; Liu, F.; Wen, X.; Tian, X.; Zhang, C. Do behavioural interventions enhance waste recycling practices? Evidence from an extended meta-analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Jaouhari, A.; Samadhiya, A.; Kumar, A.; Mulat-Weldemeskel, E.; Luthra, S.; Kumar, R. Turning trash into treasure: Exploring the potential of AI in municipal waste management—An in-depth review and future prospects. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nepal, M.; Karki Nepal, A.; Khadayat, M.S.; Rai, R.K.; Shyamsundar, P.; Somanathan, E. Low-cost strategies to improve municipal solid waste management in developing countries: Experimental evidence from Nepal. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2023, 84, 729–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albornoz-Arias, N.; Morffe Peraza, M.Á. Smuggling and social anomie on the border between Colombia and Venezuela. Estud. Front. 2023, 24, e0129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiandrino, S.; Cattuto, C.; Paolotti, D.; Schifanella, R. Combining environmental and socioeconomic data to understand determinants of conflicts in Colombia. Front. Big Data 2023, 6, 1107785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirastuti, N.M.A.E.D.; Verlin, L.; Mkwawa, I.-H.; Samarah, K.G. Implementation of Geographic Information System Based on Google Maps API to Map Waste Collection Point Using the Haversine Formula Method. J. Ilm. Tek. Elektro Komput. Inform. 2023, 9, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etim, E.; Tashi Choedron, K.; Ajai, O. Municipal solid waste management in Lagos State: Expansion diffusion of awareness. Waste Manag. 2024, 190, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Zaremohzzabieh, Z.; Rahman, H.A.; Syed Ismail, S.N.; Bin-qiang, J. Applying participatory research in solid waste management: A systematic literature review and evaluation reporting. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 5072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, A.; Kamarubiani, N.; Shantini, Y.; Heryanto, N. Community empowerment in waste management: A Meta Synthesis. In Proceedings of the First Transnational Webinar on Adult and Continuing Education (TRACED 2020), Bandung, Indonesia, 10 May 2021; pp. 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etim, E. Leveraging public awareness and behavioural change for entrepreneurial waste management. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Fan, Y.V.; Klemeš, J.J. Data analytics of social media publicity to enhance household waste management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Hayat, N.; Masud, M.M.; Makhbul, Z.K.M.; Jannat, T.; Salleh, M.F.M. Modelling the significance of value-belief-norm theory in predicting solid waste management intention and behavior. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 906002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonatti, M.; Erismann, C.; Askhabalieva, A.; Borba, J.; Pope, K.; Reynaldo, R.; Eufemia, L.; Turetta, A.P.; Sieber, S. Social learning as an underlying mechanism for sustainability in neglected communities: The Brazilian case of the Bucket Revolution project. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 6919–6937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunarti, S.; Zebua, R.S.Y.; Tjakraatmadja, J.H.; Ghazali, A.; Rahardyan, B.; Koeswinarno, K.; Suradi, S.; Nurhayu, N.; Ansyah, R.H.A. Social learning activities to improve community engagement in waste management program. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2023, 9, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, L.Y.; Wang, S.M.; Yeh, T.K. Kolb’s experiential learning theory and marine debris education: Effects of different stages on learning. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 191, 114933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafesse, S.; van Mierlo, B.; Leeuwis, C.; Lie, R.; Lemaga, B.; Struik, P.C. Combining experiential and social learning approaches for crop disease management in a smallholder context: A complex socio-ecological problem. Socio-Ecol. Pract. Res. 2020, 2, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosone, L.; Chevrier, M.; Martinez, F. When narratives speak louder than numbers: The effects of narrative persuasion across the stages of behavioural change to reduce air pollution. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1072187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Cui, J.; Sun, C.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Guan, W. The Effects of the Type of Information Played in Environmentally Themed Short Videos on Social Media on People’s Willingness to Protect the Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Li, Z.; Feng, S.; Zhang, Y. Can we ‘nudge’ people to better waste separation behaviours? Policy interventions mediated by habit, sense of separation efficiency and external environmental perceptions. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, 42, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotti, L.; Barile, L.; Manfredi, G. Improving recycling sorting behaviour with human eye nudges. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y. Promoting Decision Making and Behavioral Change: Application of Psychology and Behavioral Economics to Nudge Design. Educ. Reform Dev. 2024, 5, 1–6. Available online: https://ojs.bbwpublisher.com/index.php/erd/article/view/7589/6538 (accessed on 27 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Alifia, H.; Intyaswati, D.; Widianingsih, Y.; Simanihuruk, H.; Maryam, S. Examining the impact of @waste4change’s Instagram campaign on user attitudes towards waste management. Int. J. Sci. Educ. Cult. Stud. 2023, 2, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, D.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, B. How does information publicity influence residents’ behaviour intentions around e-waste recycling? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 133, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kala, K.; Bolia, N.B. Waste management communication policy for effective citizen awareness. J. Policy Model. 2020, 42, 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Y.; Tamas, P.A.; Harder, M.K. Information with a smile—Does it increase recycling? J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Harder, M.K. The incentives may not be the incentive: A field experiment in recycling of residential food waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anokye, K.; Mohammed, S.A.; Agyemang, P.; Agya, A.B.; Amuah, E.E.Y.; Sodoke, S.; Diderutua, E.K. From perception to action: Waste management challenges in Kassena Nankana East Municipality. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosaldo, M. Top-Down and Bottom-Up Formalization: Waste Pickers’ Struggles for Labor Rights in São Paulo and Bogotá. ILR Rev. 2023, 77, 32–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban Cantillo, O.J.; Quesada, B. Solid Waste Characterization and Management in a Highly Vulnerable Tropical City. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, F.; Abizaid, O. La Formalización de la Población Recicladora en Colombia como Prestadora del Servicio Público de Reciclaje. Logros, Oportunidades, Restricciones y Amenazas (Nota Técnica No. 12; pp. 1–56). Nota Técnica de Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) n.o 12. 2021. Available online: https://www.wiego.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/nota-tecnica-wiego-12-parra-abizaid.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Grimmer, M.; Miles, M.P. With the best of intentions: A large sample test of the intention–behaviour gap in pro-environmental consumer behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2017, 41, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, L.M.; Shiu, E.; Shaw, D. Who Says There is an Intention–Behaviour Gap? Assessing the Empirical Evidence of an Intention–Behaviour Gap in Ethical Consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobernación de Norte de Santander. Plan de desarrollo para Norte de Santander 2020-2023. [Official Document]. 2020. Available online: https://ids.gov.co/2020/PLANES/PDD/PDD_NdS_2020-2023.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2025).

| Municipality | N. Sessions | Participants (Initial) | Participants (Final Included for Results) | % Participants Municipality | Average Age (SD) | Sex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cúcuta | 10 | 109 | 90 | 30.72 | 32.44 (13.82) | Woman | 39 |

| Man | 51 | ||||||

| Los Patios | 8 | 68 | 55 | 18.77 | 39.73 (20.45) | Woman | 42 |

| Man | 13 | ||||||

| Villa del Rosario | 7 | 85 | 77 | 26.28 | 37.88 (16.54) | Woman | 62 |

| Man | 15 | ||||||

| San Cayetano | 3 | 29 | 19 | 6.48 | 33.32 (16.09) | Woman | 14 |

| Man | 5 | ||||||

| El Zulia | 7 | 68 | 52 | 17.75 | 21.87 (10.17) | Woman | 38 |

| Man | 14 | ||||||

| Total | 35 | 359 | 293 | 100 | 293 | ||

| Municipalities | Awareness About the Negative Consequences | Awareness of Economic Benefits | Awareness of Environmental Benefits | Subjective Norm | Willingness | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Cúcuta | 4.49 | 0.97 | 3.59 | 1.25 | 4.53 | 1 | 3.49 | 1.12 | 4.45 | 0.98 |

| Los Patios | 4.25 | 1 | 3.46 | 1.17 | 4.28 | 1.04 | 3.22 | 1.11 | 4.41 | 0.95 |

| Villa del Rosario | 4.4 | 1.04 | 3.34 | 1.36 | 4.41 | 1.10 | 3.34 | 1.05 | 4.35 | 1.06 |

| San Cayetano | 4.26 | 1.14 | 3.13 | 1.03 | 4.21 | 1.28 | 3.47 | 1.13 | 4.56 | 0.88 |

| El Zulia | 4.28 | 0.9 | 3.22 | 1.12 | 4.40 | 0.99 | 3.35 | 1.08 | 4.46 | 0.94 |

| General | 4.37 | 0.99 | 3.40 | 1.23 | 4.41 | 1.05 | 3.37 | 1.09 | 4.43 | 0.98 |

| Model | Estimator | df | χ2 | CFI | TLI | RMSEA [CI 90%] | SRMR | AIC | BIC | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model with four predictors | WLSMV | 55 | 194.148 | 0.977 | 0.968 | 0.05 [0.04, 0.05] | 0.05 | - | - | 0.859 |

| Model with four predictors and restricted variance in item 1 of subjective norm | WLSMV | 56 | 184.771 | 0.978 | 0.969 | 0.05 [0.04, 0.05] | 0.05 | - | - | 0.859 |

| Model with four predictors | MLR | 55 | 135.964 | 0.968 | 0.955 | 0.07 [0.06, 0.09] | 0.061 | 9167.531 | 9300.018 | 0.863 |

| Model with three predictors and restricted variance in item 1 of subjective norm | WLSMV | 39 | 113.466 | 0.986 | 0.981 | 0.04 [0.03, 0.05] | 0.043 | - | - | 0.860 |

| Model with three predictors | MLR | 38 | 90.771 | 0.978 | 0.967 | 0.07 [0.05, 0.09] | 0.056 | 7192.871 | 7295.916 | 0.862 |

| Category | Definition | Code | Frequency of Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Problem perception | References to MSW and its management as a problematic issue with environmental and/or community-level consequences. | Environmental Pollution | 12 |

| Public Health and Safety Risks | 11 | ||

| Psychosocial barriers | References of individual or social barriers to participation in MSW separation and delivery processes. | Lack of environmental literacy | 19 |

| Apathy | 12 | ||

| Resistance to Change | 7 | ||

| Contextual barriers | References to perceived inadequacies in resources, infrastructure, or systems that hinder the separation and delivery of MSW. | Insufficient public education and awareness campaigns on MSW management | 21 |

| Insufficient MSW bins | 15 | ||

| Failures in collection systems for MSW management | 8 | ||

| Suggestions for Enhancing Local MSW Management | References to strategies suggested by participants for local programs to effectively implement pro-environmental management of MSW. | Public education on MSW management | 30 |

| Installation of MSW bins | 22 | ||

| Awareness Campaigns | 17 | ||

| Incorporating informal recyclers into MSW management programs | 6 | ||

| Enhancing regulations and public policies | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aristizábal Cuellar, J.A.; Puerto-Rojas, E.; Correa-Galindo, S.N.; Sierra Puentes, M.C. A Community-Based Intervention Proposal for Municipal Solid Waste Management: Analyzing Willingness, Barriers and Spatial Strategies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136206

Aristizábal Cuellar JA, Puerto-Rojas E, Correa-Galindo SN, Sierra Puentes MC. A Community-Based Intervention Proposal for Municipal Solid Waste Management: Analyzing Willingness, Barriers and Spatial Strategies. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):6206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136206

Chicago/Turabian StyleAristizábal Cuellar, Jose Alejandro, Elkin Puerto-Rojas, Sharon Naomi Correa-Galindo, and Myriam Carmenza Sierra Puentes. 2025. "A Community-Based Intervention Proposal for Municipal Solid Waste Management: Analyzing Willingness, Barriers and Spatial Strategies" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 6206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136206

APA StyleAristizábal Cuellar, J. A., Puerto-Rojas, E., Correa-Galindo, S. N., & Sierra Puentes, M. C. (2025). A Community-Based Intervention Proposal for Municipal Solid Waste Management: Analyzing Willingness, Barriers and Spatial Strategies. Sustainability, 17(13), 6206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136206