The Business Innovation of Consumer Choices and Challenges for Economic Sustainability Practices and Law

Abstract

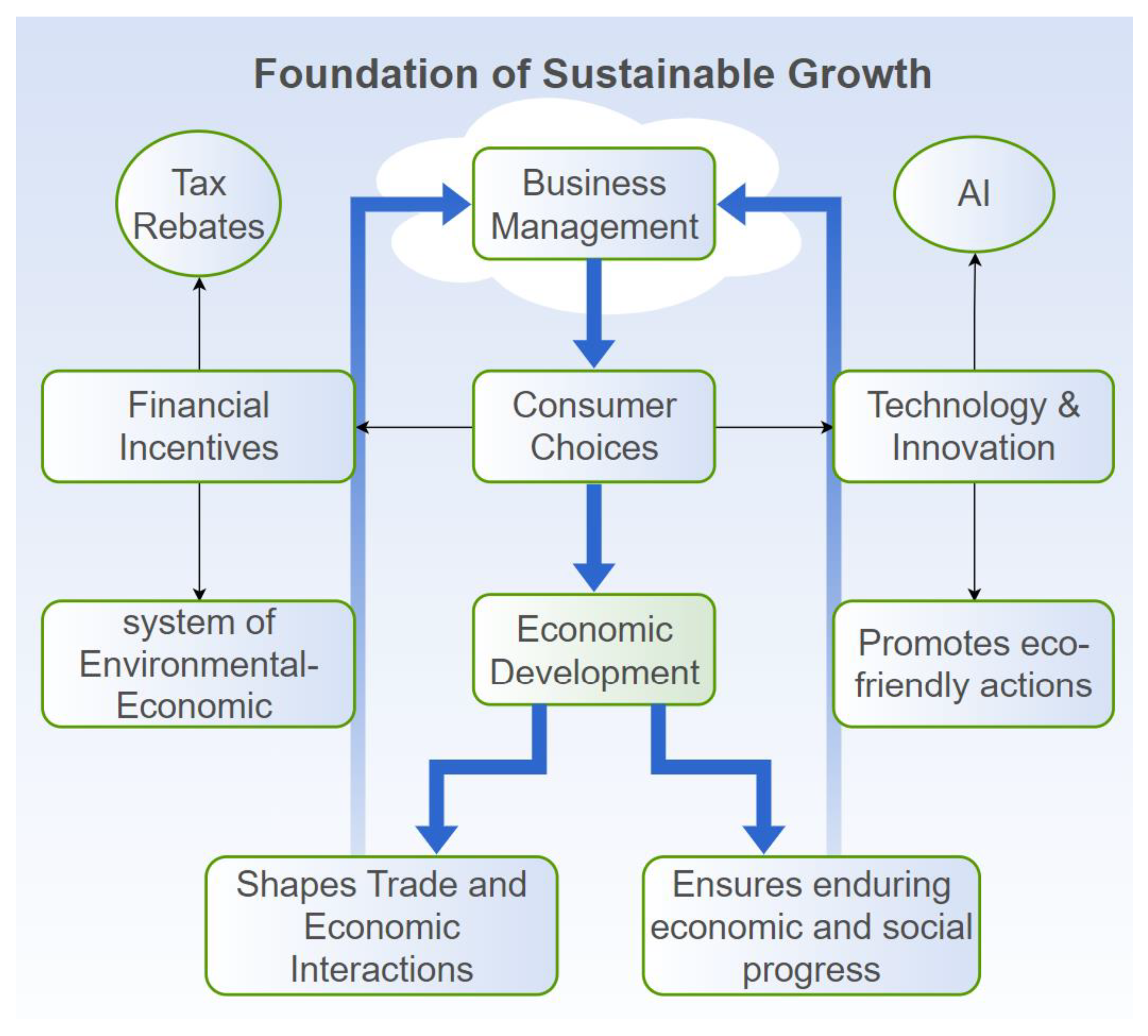

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Consumer Behavior and Digital Economic Transformation

2.2. Sustainable Business Strategies and Supply Chains

2.3. The Role of Technology-Enabled Sustainability

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Growth of China’s Imports vs. East Asia and Pacific Region

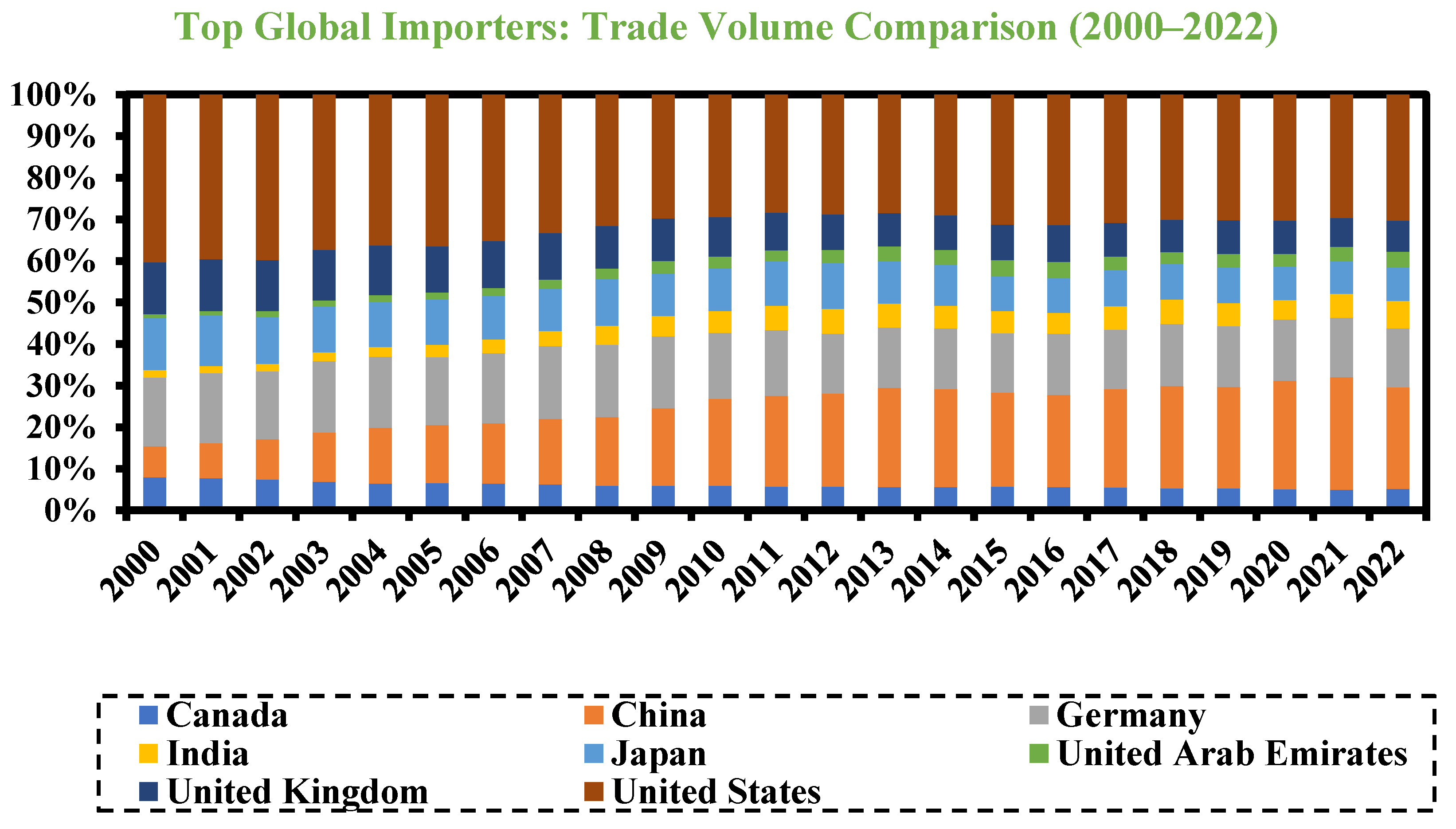

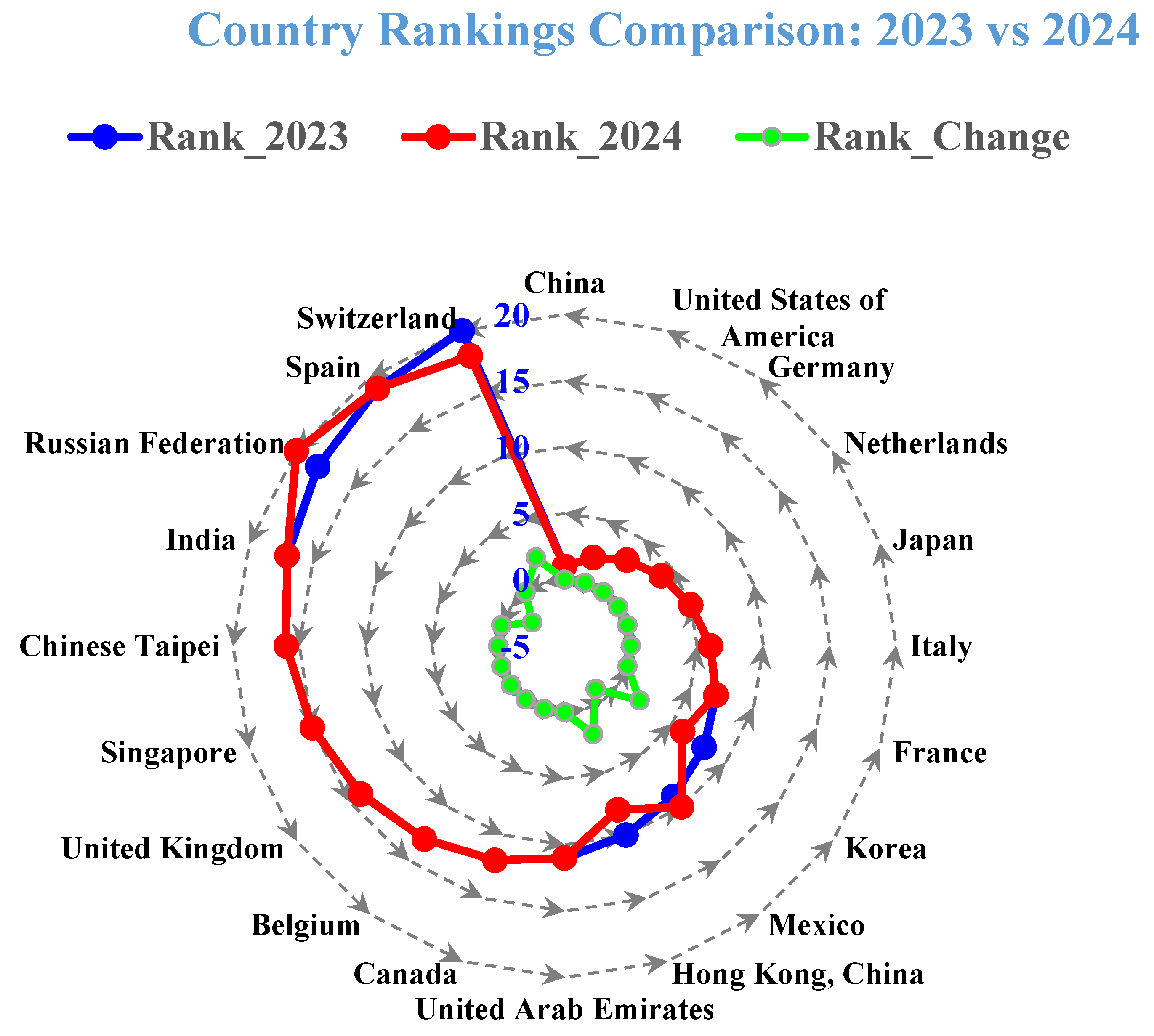

4.2. The Share of the Top Economies in World Merchandise Exports

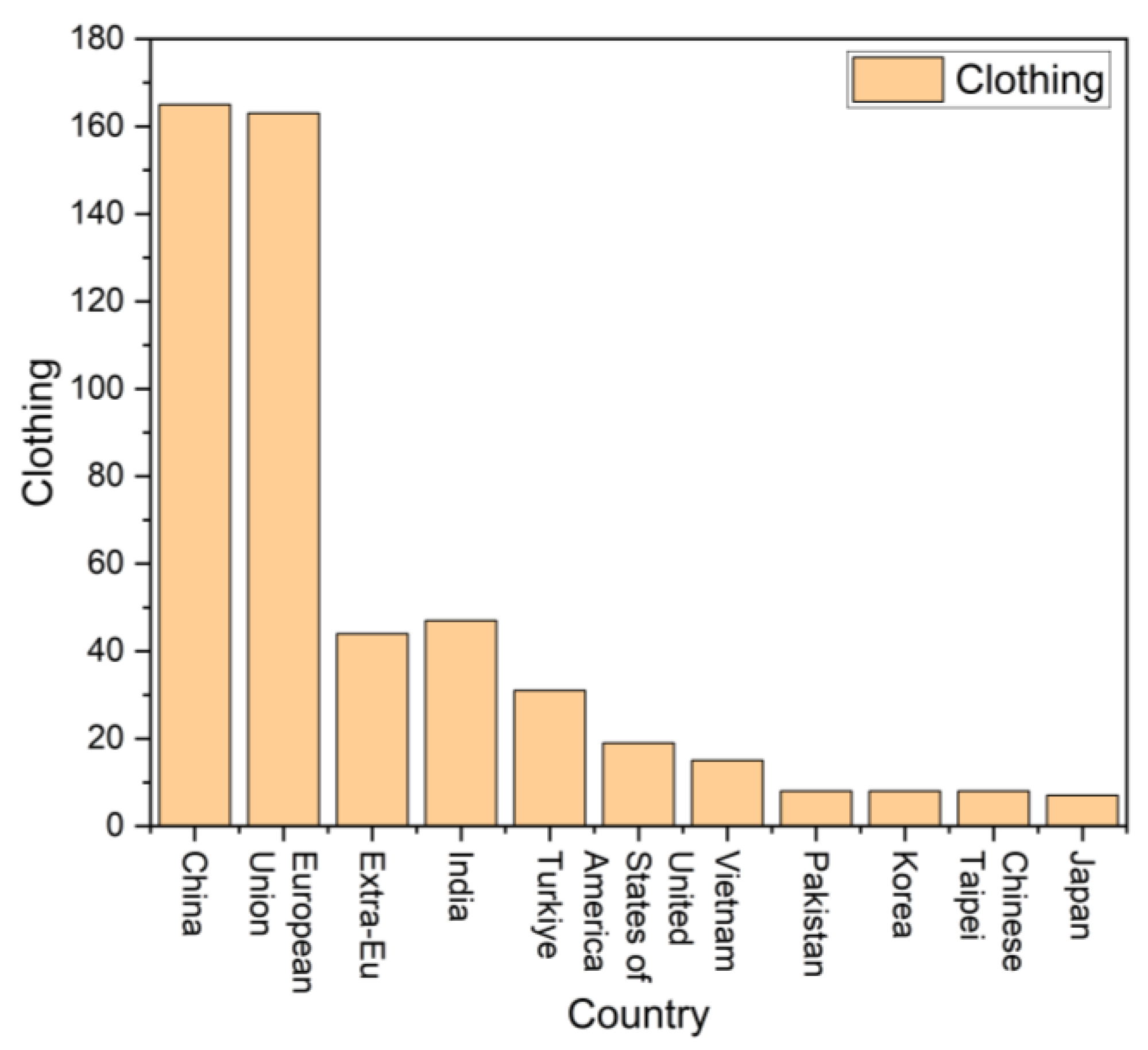

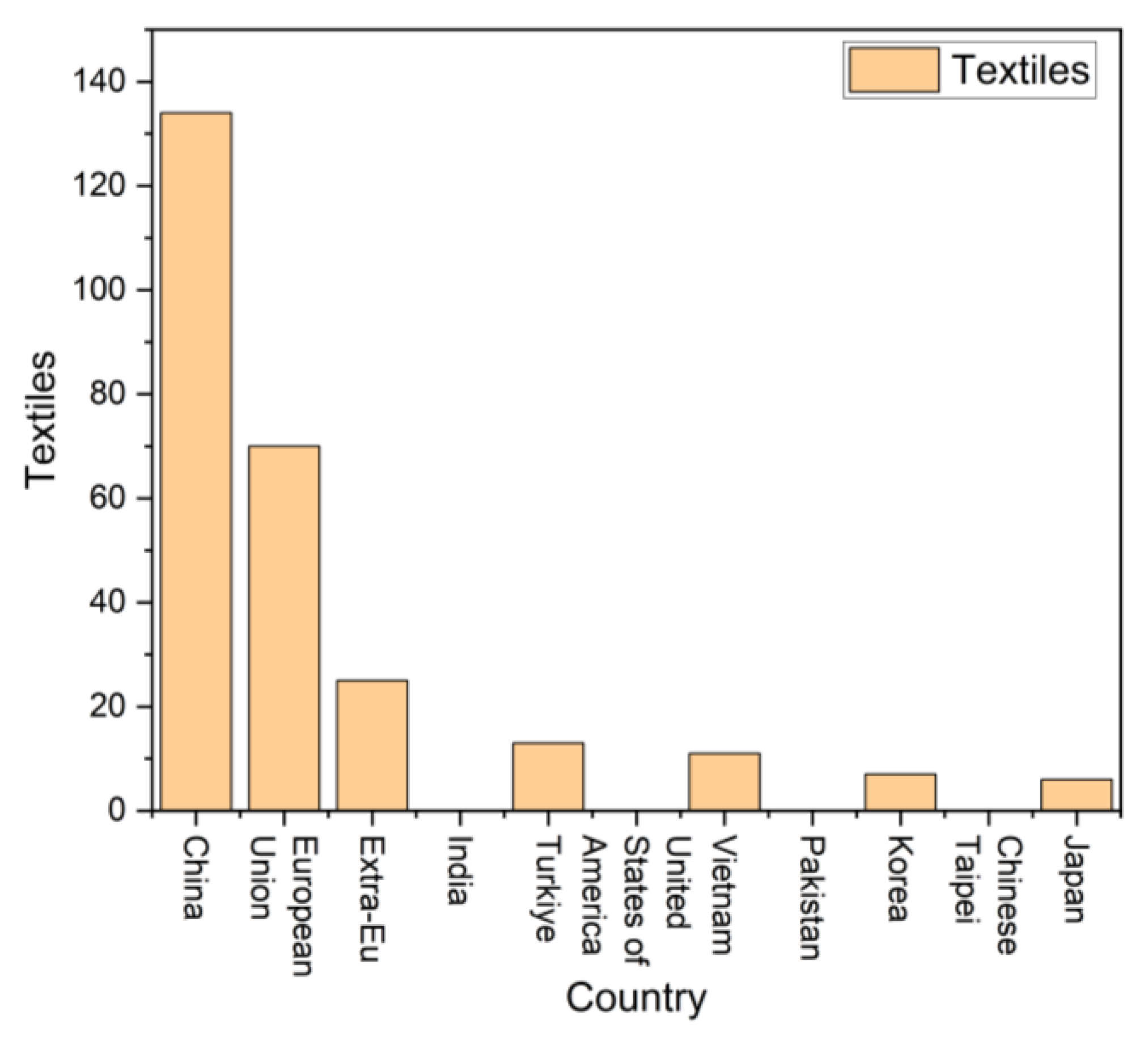

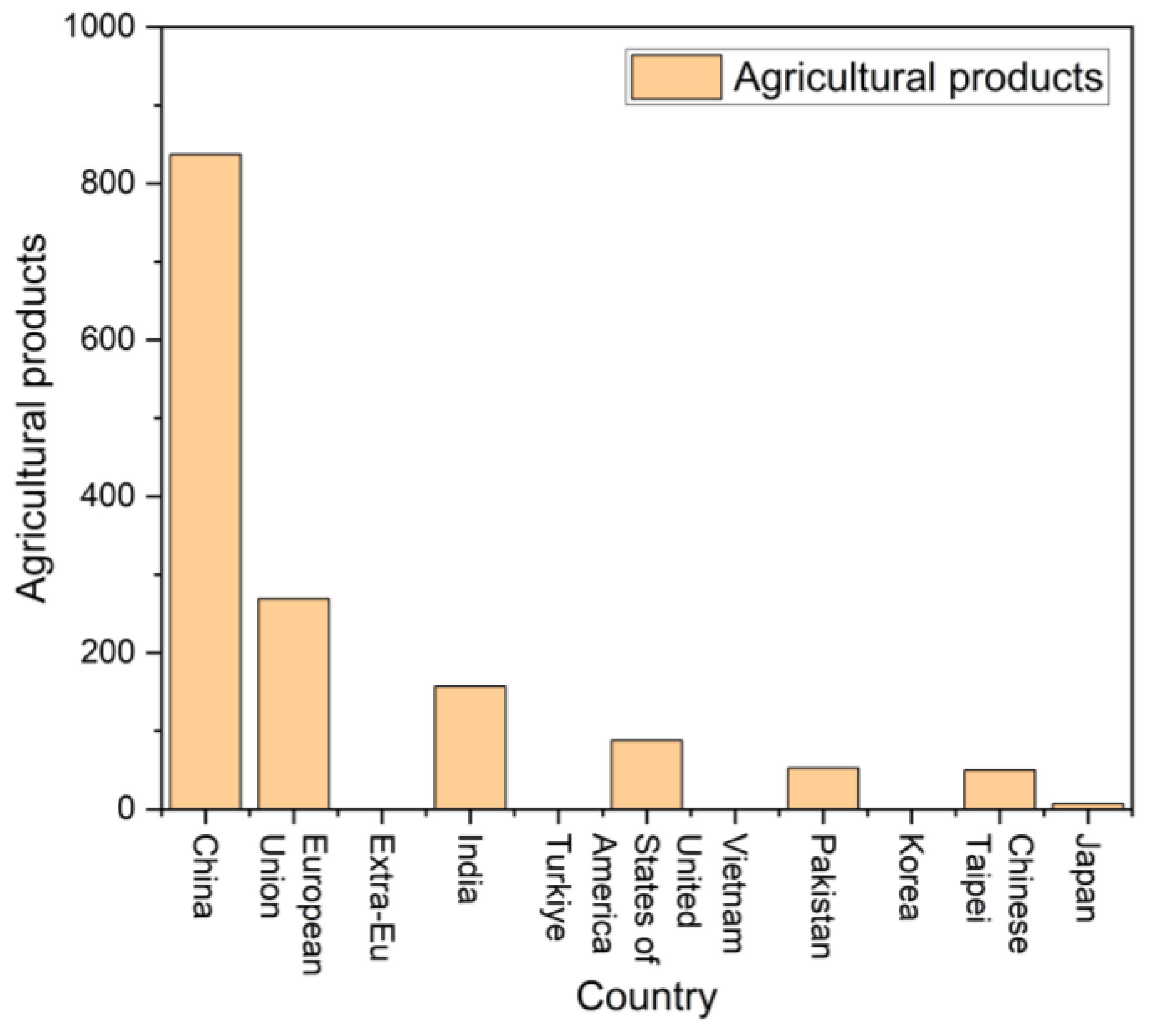

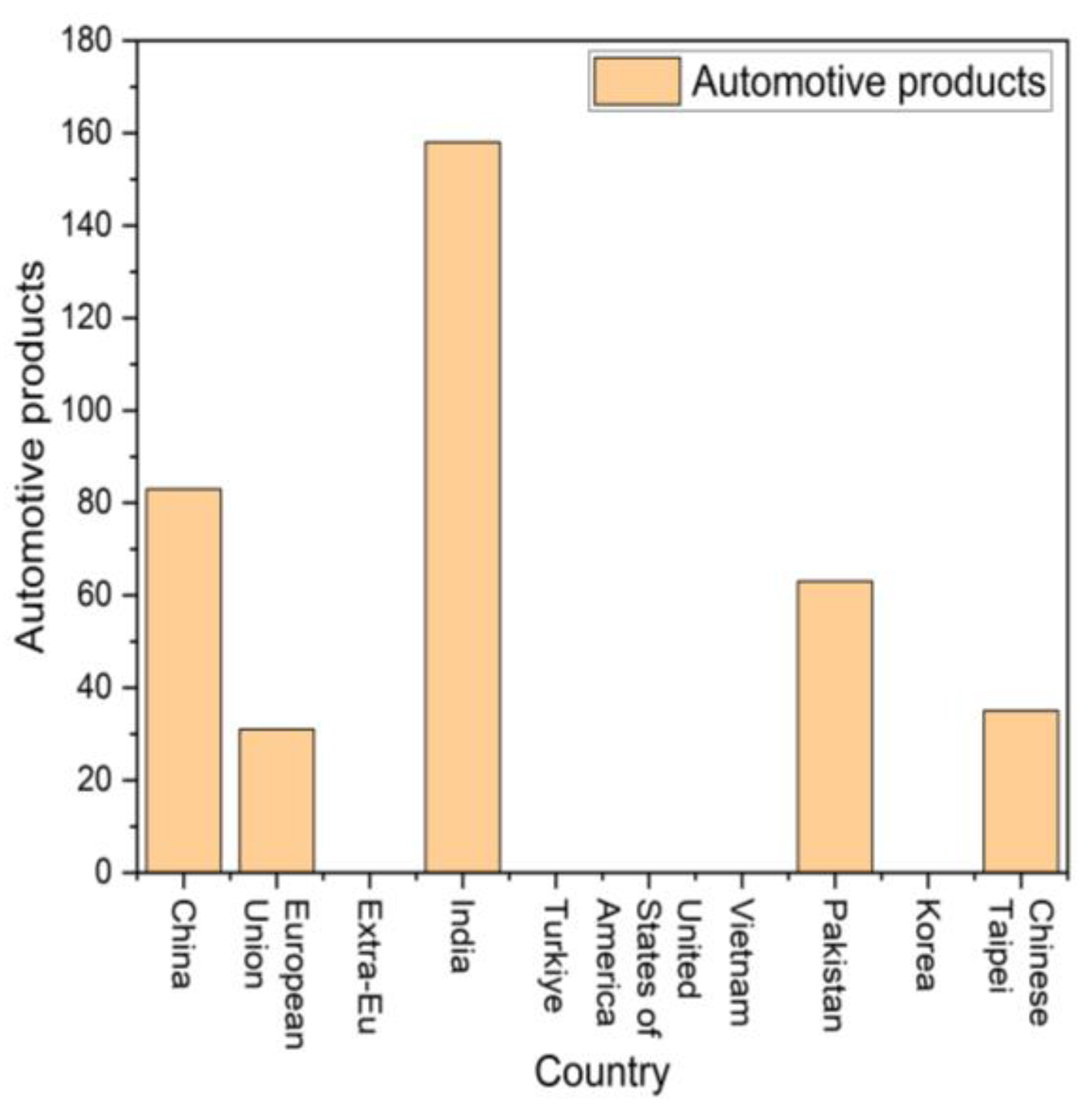

4.3. Export of Selected Product Groups and Subgroups

4.4. The US Tariff Policies

4.5. Global Trade and Tariff-Related Legal Developments

4.6. Impacts of Tariffs

5. Analysis and Discussion

6. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

6.1. Implications

6.2. Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBAM | Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism |

| WTO | World Trade Organization |

| ACFTA | Chinese–ASEAN Free Trade Area |

| GATT | General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| EU | European Union |

| DSB | Dispute Settlement Body |

| DOJ | Department of Justice |

| ASEAN | Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

References

- Sirenko, P.; Balian, I.; Martyniak, I.; Malakhova, T.; Bakushevych, I. The Relationship between International Trade Relations and Regional Development: A Comprehensive Analysis and Assessment of Influencing Factors. Multidiscip. Sci. J. 2024, 6, 2024ss0220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Economic Impact of Tariffs on Business|McKinsey. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/geopolitics/our-insights/tariffs-and-global-trade-the-economic-impact-on-business (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Khaskheli, M.B.; Zhao, Y. The Sustainability of Economic and Business Practices Through Legal Cooperation in the Era of the Hainan Free Trade Port and Southeast Asian Nations. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naudé, W.; Cameron, M. Retaliation Against Trump’s Trade War: Why and How the EU Should Find Alternative Export Markets. SSRN J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, N. Trump’s Trade War Is about More than Trade. Available online: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/trumps-trade-war-is-about-more-than-trade/ (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Badri Narayanan, G.; Sen, R.; Srivastava, S. The Potential Impact of Tariff Liberalisation on India’s Automobile Industry Global Value Chain Trade: Evidence From an Economy-Wide Model. Foreign Trade Rev. 2025, 60, 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, B. On Trade, Donald Trump Breaks With 200 Years of Economic Orthodoxy. The New York Times, 10 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thebaud, R.L. How Could Tariffs Affect Consumers, Business and the Economy? Available online: https://www.ucdavis.edu/magazine/how-could-tariffs-affect-consumers-business-and-economy (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Chow, D.C.K.; Sheldon, I.M. Understanding the Economic and Political Effects of Trump’s China Tariffs. Wm. Mary Bus. L. Rev. 2020, 12, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Imposes Tariffs on Imports from Canada, Mexico and China. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/02/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-imposes-tariffs-on-imports-from-canada-mexico-and-china/ (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Checkmate or Stalemate: India’s Trade and Output Losses Under U.S. Reciprocal Tariffs by Rishabh Atray, Ramya KR:SSRN. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5155287 (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Lee, C.-W.; Khan, A.Z. The Impact of Trump’s Tariff Policies on Global Trade Dynamics: A Case Study of Major U.S. Trade Partners. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Aff. 2025, 10, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danquah, D.A.; Mensah, E.; Barnor, C. Optimizing Foreign Direct Investment for Sustainable Trade Balance Improvement: The Case of a Developing Economy. SN Bus. Econ. 2025, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.D.; Kovacic, W.E.; Müller, A.C.; Sporysheva, N. Competition Policy, Trade and the Global Economy: Existing WTO Elements, Commitments in Regional Trade Agreements, Current Challenges and Issues for Reflection; World Trade Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- A New Tariff Paradigm: How Businesses Can Respond. Available online: https://www.grantthornton.com/insights/articles/tax/2025/new-tariff-paradigm-how-businesses-can-respond (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Akram, H.W. Digital Transformation in Logistics and Supply Chain Management Practices. In Ecological and Human Dimensions of AI-Based Supply Chain; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 27–48. ISBN 9798369374788. [Google Scholar]

- The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on International Trade. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-impact-of-artificial-intelligence-on-international-trade/ (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Piccoli, C. Pieter de Graeff (1638–1707) and His Treffelyke Bibliotheek: Exploring and Reconstructing an Early Modern Private Library as a Book Collection and as a Physical Space; Brill: Aylesbury, UK, 2025; ISBN 978-90-04-71174-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S. Challenging the Use of Special 301 against Measures Promoting Access to Medicines: Options Under the WTO Agreements. J. Int. Econ. Law 2016, 19, 51–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Personal Data Protection and Related Legislation in China: The Implications for International Trade Law—ProQuest. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/d105c7ea1d3b9330708afa6c09fe875c/1?cbl=2026366&diss=y&pq-origsite=gscholar (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Bouët, A.; Sall, L.M.; Zheng, Y. Towards a Trade War in 2025: Real Threats for the World Economy, False Promises for the US; Working Papers; CEPII Research Center: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, C. Centralization of Responsibilities for the Screening of Foreign Direct Investments in the European Union and Its Member States. In The Law and Geoeconomics of Investment Screening; Pohl, J.H., Hindelang, S., Papadopoulos, T., Wiesenthal, J., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 183–203. ISBN 978-3-031-75554-5. [Google Scholar]

- Joyner, D. Economic Nationalism as the Fourth Era of International Trade Law. Manch. J. Int. Econ. Law 2025. forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandjoyo, K.A.; Sunitiyoso, Y. Impact Analysis of Law No. 9 of 2018 in Administration of Tariff Service Non-Tax Revenue in Indonesia. J. Manaj. Keuang. Publik 2023, 7, 158–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radojević, T.; Rajin, D.; Nikolić, J.; Yildirim, S. The WTO’S influence on the global economy and modern business dynamics. Eur. J. Appl. Econ. 2025, 22, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erni, W. Penerapan kebijakan hukum atas perjanjian asean china free trade area (acfta) terhadap pembebasan bea masuk sektor industri tekstil usaha mikro kecil dan menengah. J. Lege Ferenda Trisakti 2025, 3, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutner, T. Explaining the Gaps between Mandate and Performance: Agency Theory and World Bank Environmental Reform. Glob. Environ. Politics 2005, 5, 10–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Hu, X.; Ning, Y.; Cong, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xu, T.; Shi, X. Quantitative Assessment of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: Impacts on China–EU Trade and Provincial-Level Vulnerabilities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.M. Multi-Purpose Green Industrial Policy and the WTO: An Unavoidable Clash? World Trade Rev. 2025, 24, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y. Green Trade Barriers under the Developing Country Perspective. Future Hum. Image 2024, 21, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okechukwu, V.U.; Onwukeme, V.I.; Eze, V.C.; Aralu, C.C. Concentration Levels and Pollution Status of Selected Heavy Metals in Active Dumpsites in Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria. Chem. Rep. 2024, 5, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneejuk, P.; Yamaka, W. The Impact of Higher Education on Economic Growth in ASEAN-5 Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacerdoti, G.; de Stefano, C. The WTO and Its Dispute Settlement System in 2023–2024: Navigating the Crisis, Engaging in Reform, Adressing Trade and Climate Change; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- The Development of China’s Extraterritorial Mineral Resources Exploration and Exploitation in the Deep Seabed and Outer Space: An Evaluation from Policy and Legal Perspectives—ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301420724004276 (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Sizhi, G. Observations & Thoughts on the Transformation of Supply Chains in East Asia & Their Reconstruction.|EBSCOhost. Available online: https://openurl.ebsco.com/contentitem/gcd:179700342?sid=ebsco:plink:crawler&id=ebsco:gcd:179700342 (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- How Demand Shocks “Jumpstart” Technological Ecosystems and Commercialization: Evidence from the Global Electric Vehicle Industry|Strategy Science. Available online: https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1287/stsc.2022.0075 (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Bilawal Khaskheli, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Shamsi, I.H.; Shen, C.; Rasheed, S.; Ibrahim, Z.; Baloch, D.M. Technology Advancement and International Law in Marine Policy, Challenges, Solutions and Future Prospective. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1258924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawn, S.; Ramakrishna, A.; Ramesh, M.; Das, S.S.; Rao, K.D.; Islam, M.d.M.; Selim Ustun, T. Integration of Renewable Energy in Microgrids and Smart Grids in Deregulated Power Systems: A Comparative Exploration. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2024, 5, 2400088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katterbauer, K.; Syed, H.; Özbay, R.D.; Yılmaz, S.; de Kiev, L.C. Taxation of Artificial Intelligence Solutions—A Chinese Approach. J. Recycl. Econ. Sustain. Policy 2025, 4, 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- De Marco, S. The Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Automated Checks of Tax Declarations. Critical Reconstructive Insights. In Generative Artificial Intelligence and Fifth Industrial Revolution; Marino, D., Monaca, M.A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 151–157. ISBN 978-3-031-73880-7. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Åhman, M.; Algers, J.; Nilsson, L.J. Decarbonizing the Asian Steel Industries through Green Hot Briquetted Iron Trade. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 219, 108275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado, S.; Veloso, C.M. Artificial Intelligence in Accounting: Driving Value Co-Creation, Compliance, and Ethical Transformation. In Empowering Value Co-Creation in the Digital Era; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 75–102. ISBN 9798337317427. [Google Scholar]

- Borzenko, O.; Panfilova, T. Escalating Crisis in the Governance of the Global Trading System. BUKETOV Bus. Rev. 2023, 112, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasshyvalov, D.; Portnov, Y.; Sigaieva, T.; Alboshchii, O.; Rozumnyi, O. Navigating Geopolitical Risks: Implications for Global Supply Chain Management. Multidiscip. Rev. 2024, 7, 2024spe017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, I.; Sofi, M.S. Anatomy of Trade Disputes: Mapping Patterns and Trends of WTO Dispute Initiations (1995–2023). Decision 2024, 51, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucharom, R.S.; Suriaamadja, T.T.; Januarita, R.; Jaya, B.P.M.; Maharani, D.G.; Taufiqurrohman, A. WTO Subsidies Agreement on Fisheries (2022–2024): Agreed Terms and Implications for Indonesia. J. IUS Kaji. Huk. Dan Keadilan 2024, 12, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumaila, U.R.; Alam, L.; Abdallah, P.R.; Aheto, D.; Akintola, S.L.; Alger, J.; Andreoli, V.; Bailey, M.; Barnes, C.; Ben-Hasan, A.; et al. WTO Must Complete an Ambitious Fisheries Subsidies Agreement. Npj Ocean Sustain. 2024, 3, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China GDP Growth Rate 1961–2025|MacroTrends. Available online: https://www.macrotrends.net/global-metrics/countries/chn/china/gdp-growth-rate (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- May-Boroda, G.N.; Gorbunova, N.N.; Gorbunova, M.A. Artificial Intelligence and Its Impact on the Economy and Business. In Big Data and Artificial Intelligence for Decision-Making in the Smart Economy; Karbekova, A.B., Žák, L., Milenković, I., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 227–233. ISBN 978-3-031-78686-0. [Google Scholar]

- Dursun, E.; Amani, A.; Yawar, M.E. The Legal Framework of the World Trade Organization from the Perspective of Game Theory in International Law. Glob. Spectr. Res. Humanit. 2025, 2, 71–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaisse, J.; Su, X. Normative Realignment in Domestic Trade Barriers Procedures: Driving Unilateralism in the EU, US, and China. World Trade Rev. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbandi, T. Necessary Evil: Water Treaties and International Trade. Rev. World Econ. 2024, 160, 1329–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China GDP Annual Growth Rate. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/china/gdp-growth-annual (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS)|Data on Export, Import, Tariff, NTM. Available online: https://wits.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Wang, S.; Jiang, X.; Khaskheli, M.B. The Role of Technology in the Digital Economy’s Sustainable Development of Hainan Free Trade Port and Genetic Testing: Cloud Computing and Digital Law. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Yang, S.; Lou, Z.; Ali, A. The Impact of Japan’s Discharge of Nuclear-Contaminated Water on Aquaculture Production, Trade, and Food Security in China and Japan. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Trade Organization—Global Trade. Available online: https://www.wto.org/index.htm (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Weinhardt, C.; Farias, D.B.L. Developing Countries in Global Trade Governance: Comparing Norms on Inequality in the WTO and GSP Schemes. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2025, 32, 1239–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Trade Statistics 2024. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/world_trade_statistics_e.htm (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Yan, M.; Liu, H. The Impact of Digital Trade Barriers on Technological Innovation Efficiency and Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnangnon, S.K. Effect of Special and Differential Treatment Flexibilities in WTO Rules on Trade Reforms, Manufactured Exports and Export Upgrading in the Least Developed Countries; ZBW—Leibniz Information Centre for Economics: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, L.; Das, M. Does the World Trade Organization Enable Biosecurity and Trade for Importers and Exporters? World Trade Rev. 2024, 23, 448–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, C.; Li, S.K. Measuring the Technical Efficiency of Firms with Domestic Sales and Exports: Revisiting China’s Accession to WTO. 2025. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5084970 (accessed on 7 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Impact of Recent US Tariffs on ASEAN Businesses. Available online: https://www.ey.com/en_id/technical/tax-alerts/impact-of-recent-us-tariffs-on-asean-businesses (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Chen Ziyan, US Business Community Alarmed by Tariff Impacts. Available online: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202505/02/WS68140077a310a04af22bd388.html (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Clausing, K.A. US International Corporate Taxation after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. J. Econ. Perspect. 2024, 38, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Businesses Rally Behind President Trump’s Tariffs to Save Manufacturing. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/articles/2025/04/american-businesses-rally-behind-president-trumps-tariffs-to-save-manufacturing/ (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Global Air Freight Rates Increase Sharply Due to US Tariff Wave. Available online: https://reallogistics.vn/insights/market-updates/global-air-freight-rates-increase-sharply-due-to-us-tariff-wave (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- US Tariffs Could Seriously Disrupt $6.1 Billion EU Exports of Packaging and Food Processing Machinery, Says GlobalData; GlobalData: Sydney, Australia, 2025.

- US Economy Unexpectedly Shrinks, Trump Blames Biden—The Korea Herald. Available online: https://www.koreaherald.com/article/10478542 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Perulli, A. Labour Law’s Perspective in the Global Dimension. In A Global Labour Law; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2024; ISBN 978-1-00-351266-0. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, M.J.L.; Philippe, H.; Justin, A.; Lizbeth, R.-J.; Kirsten, L.; Courtney, E. U.S. Imposes 10% Baseline Tariffs; Higher Reciprocal Tariffs for Targeted Countries. Available online: https://www.tradecomplianceresourcehub.com/2025/04/03/u-s-imposes-10-baseline-tariffs-higher-reciprocal-tariffs-for-targeted-countries/ (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Big Tech’s Fortunes Diverge as AI Powers Cloud, Tariffs Hit Consumer Electronics. Available online: https://www.chinadailyhk.com/hk/article/610868#Big-Tech's-fortunes-diverge-as-AI-powers-cloud%2C-tariffs-hit-consumer-electronics-2025-05-02 (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Tariffs, Green Technologies, and the VCM. Available online: https://www.clearbluemarkets.com/knowledge-base/tariffs-green-technologies-and-the-vcm (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Sapre, A.A.; Shah, S.A.; Mushtaq, S.M.; Singh, S. Power Dynamics and Institutional Resilience in the Liberal International Order: A Legal Perspective. In International Relations Theory and Philosophical Political Insights into Conflict Management; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 113–142. ISBN 9798369396261. [Google Scholar]

- Svetlicinii, A.; Su, X. The Unsettled Governance of the Dual-Use Items under Article XXI(b)(Ii) GATT: A New Battleground for WTO Security Exceptions. World Trade Rev. 2025, 24, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaskheli, M.B.; Wang, S.; Yan, X.; He, Y. Innovation of the Social Security, Legal Risks, Sustainable Management Practices and Employee Environmental Awareness in The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumba, W. Article: WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement: Has the Trade Facilitation Agreement Improved Aspects of GATT Article VIII? Glob. Trade Cust. J. 2024, 19, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, M. Chapter 25 Intertemporal Issues in the Interpretation of GATT Article XXI; Brill: Aylesbury, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dobhal, A.; Mavroidis, P.C.; Jimenez-Moreira, L.; Sasmal, S.; Wolfe, R. Do Private Actors Have Rights under the WTO? The Motivation for and (Inadequate) Implementation of GATT Article X. J. World Trade 2024, 58, 4514. [Google Scholar]

- Mushkat, R. Authoritarian International Law: An Unfinished Research Odyssey. Cardozo Int’l Comp. L. Rev. 2024, 7, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Sieber-Gasser, C. Multilateral Rules on Trade in Goods—Tariff Barriers. In The International Law of Economic Integration; Chaisse, J., Herrmann, C., Eds.; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, X.; Zhao, J. Enhancing Sustainable Development Through Digital Service Trade Liberalization: Analyzing the Effects and Mechanisms on Bilateral Imports. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangzhou Commerce Bureau Responds to Rumors About Shein Supply Chain Relocation. Available online: http://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzA5NTIyNTEzMg==&mid=2650651680&idx=2&sn=5d60f1ccb940bfcdc9c837b23dfdb893&chksm=8932cef6fd82bce8added884d9819ab36c16a876ad64f4df164f4ba69a54d4032348fa3877b2#rd (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Ni, K.-J. Can the CPTPP’s Digital Format on Data Flows Serve a Role Model for the WTO? J. World Trade 2024, 58, 989–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Innovation of Global Trade Through Strategic Policies | |

|---|---|

| Advantages and Disadvantages of Sustainability in Business and Consumer Choices | |

| Economic Transformation | ● The Role of Tariffs in Driving Digital Economic Challenges and Growth. ● Shifts Markets Unpredictably, Risking Long-Term Instability. |

| Business Development | ● The Impact of Tariffs on Business Growth and Innovation. ● Raises Costs, Limits Growth, and Discourages Foreign Investment. |

| Consumer Choices | ● Encourage Consumers to Support Local Businesses and Farmers. ● Promote Programs That Encourage Consumers to Recycle. |

| Legal Framework | ● The Legal Structure Governs Tariff Implementation–Enforcement. ● Triggers Lawsuits, Violates Treaties, and Complicates Compliance. |

| World Trade Organization Role | ● The Influence of the WTO on Global Tariff Policies. ● Undermines Global Trade Rules, Inviting Sanctions. |

| AI Mitigation | ● The Use of AI to Minimize Negative Tariff Effects. ● Hinders Tech Collaboration and Slows AI Innovation. |

| Supply Chain Disruptions | ● Disruptions Accelerate Localization, Reducing Future Vulnerability. ● Delays Production, Increases Shortages, and Raises Prices. |

| Date | US Action | Targeted Countries | Tariff Details | China’s Retaliation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 April 2025 | Trump announces reciprocal tariffs under IEEPA/NEA authority | Global | 10% baseline tariff on all imports (effective 5 April 2025). Higher rates for trade-deficit partners (e.g., China: 34%, Vietnam: 46%, EU: 20% from 9 April 2025) | China had already imposed 15% tariffs on US farm goods (effective 10 March 2025) |

| 5 April 2025 | The baseline 10% tariff takes effect | All except China | A 10% tariff applies to non-exempt goods. Excludes Canada/Mexico (25% under USMCA rules) | China raises tariffs on US goods from 84% to 125% (effective 12 April 2025) |

| 9 April 2025 | Country-specific tariffs begin | China, EU, Vietnam | China: A tariff of 145% (125% new + 20% existing). Vietnam: 46%, India: 26%, EU: 20% | China adds 34% tariffs on US imports (effective 10 April 2025) |

| 10 April 2025 | Auto tariffs take effect | Global automakers | 25% tariff on imported cars and auto parts (phased from 3 April 2025 to 3 May 2025) | China suspends imports of US lumber and disqualifies US soybean firms |

| 12 April 2025 | China’s retaliatory tariffs escalate | United States | - | 125% tariffs on all US goods (effective 12 April 2025). Export controls on critical minerals |

| Year | Laws | Tags | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | US Section 232 Tariffs (Steel and Aluminum) | Trade Protectionism, National Security, WTO Dispute | Imposed 25% on steel and 10% on aluminum imports; challenged in the WTO by EU, China, and others |

| 2018 | EU’s Retaliatory Tariffs (WTO-Compliant Countermeasures) | WTO Compliance, Trade War, Retaliation | The EU imposed tariffs on US goods (bourbon, motorcycles) in response to Section 232 |

| 2019 | USMCA (US–Mexico–Canada Agreement) | Digital Trade, Labor Standards, Supply Chains | Replaced NAFTA and introduced stricter labor/environmental rules and digital trade provisions |

| 2020 | EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, Proposal | Climate Law, Carbon Tariffs, WTO Compliance | Imposes carbon costs on imports to align with EU climate goals; WTO compatibility debated |

| 2021 | China’s Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law | Digital Economic Sovereignty, Retaliatory Measures | Allows China to counter foreign sanctions (US tariffs, tech bans) |

| 2022 | Semiconductor Supply Chains, Export Controls | Subsidizes Domestic Chip Production and Restricts Tech Exports to China | US Congress |

| 2023 | WTO Moratorium on Digital Tariffs (Extended) | Digital Trade, E-Commerce, AI Governance | Extended ban on customs duties on electronic transmissions (e.g., software, AI models) |

| 2024 | EU AI Act (World’s First Comprehensive AI Law) | Artificial Intelligence, Ethical AI, Compliance | Classifies AI risks, bans specific uses (social scoring), and impacts global AI trade |

| 2025 | Trump’s 145% Tariffs on Chinese Goods (Updated Trade Policy) | Trade War, Supply Chain Shifts, Retaliation | Expanded tariffs on EVs, batteries, and semiconductors; China retaliates with export curbs |

| 2025 | ASEAN Digital Economy Framework Agreement | Digital Trade, Cross-Border Data Flows, AI Integration | It aims to harmonize digital trade rules among ASEAN members, which affects AI-driven businesses |

| Category | Indicators | Impact | Legal Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI and Technology | Chip shortages Nvidia’s AI processors. Rising R&D costs due to import taxes. | Tariffs inflate costs for AI infrastructure, delaying innovation. Firms like OpenAI face pricier hardware. | WTO disputes over semiconductor tariffs; the US CHIPS Act incentivizes domestic production. |

| Digital Economic Growth | 0.3% Q1 2025 GDP contraction (US). Trade deficit shifts (ASEAN exemptions sought). | Higher consumer prices and reduced trade volumes strain economies. Recession risks escalate. | America First policies clash with WTO non-discrimination principles. |

| Business Adaptation | Price hikes (e.g., Shein +51%). Nearshoring (Apple to India). | Companies relocate supply chains or absorb costs, squeezing margins. SMEs face existential threats. | The Foreign Pollution Fee Act (FPFA) penalizes carbon-intensive imports, altering sourcing. |

| Sustainable Supply Chains | EU CBAM vs. US FPFA. Plastic vs. metal packaging shifts. | Tariffs accelerate green transitions (beverage firms adopting plastic bottles) but raise compliance costs. | Climate laws intersect with trade rules, creating legal ambiguities. |

| Labor Markets | 25% hiring slowdown (tariff uncertainty). AI-driven job displacement (PayPal’s chatbot) | Automation surges as firms cut labor costs, exacerbating unemployment in vulnerable sectors. | Trade-linked labor policies (immigration raids) worsen shortages. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xia, L.; Lai, Z.; Khaskheli, M.B. The Business Innovation of Consumer Choices and Challenges for Economic Sustainability Practices and Law. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135968

Xia L, Lai Z, Khaskheli MB. The Business Innovation of Consumer Choices and Challenges for Economic Sustainability Practices and Law. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):5968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135968

Chicago/Turabian StyleXia, Linhua, Zhuiwen Lai, and Muhammad Bilawal Khaskheli. 2025. "The Business Innovation of Consumer Choices and Challenges for Economic Sustainability Practices and Law" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 5968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135968

APA StyleXia, L., Lai, Z., & Khaskheli, M. B. (2025). The Business Innovation of Consumer Choices and Challenges for Economic Sustainability Practices and Law. Sustainability, 17(13), 5968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135968