Abstract

The empowerment of rural women through sustainable entrepreneurship is pivotal for fostering economic development and social transformation in developing communities. This study examines the impact of university social responsibility (USR) programs on strengthening sustainable entrepreneurship among rural women, emphasizing the mediating role of economic empowerment. Utilizing a structural equation model (SEM), we explore causal pathways between USR interventions, entrepreneurial capacities, and the sustainability of rural businesses. Key dimensions analyzed include economic resources, social networks, and psychological self-efficacy, as well as their interrelation with community development. The findings demonstrate that multidimensional USR programs integrating technical training, social support, and economic resources significantly enhance entrepreneurial resilience and value chain integration. Notably, the analysis reveals that economic empowerment mediates the relationship between USR programs and business sustainability, with improvements in community participation and ICT quality identified as critical drivers. Furthermore, the post-intervention results highlight a shift from technology access challenges to a focus on ICT content quality and psychosocial development, reflecting maturity in community adaptation and resource utilization. This research provides empirical evidence supporting the effectiveness of USR programs in catalyzing sustainable transformations in rural contexts. The results offer actionable insights for designing targeted interventions that integrate technical, social, and economic dimensions, contributing to the advancement of sustainable entrepreneurship and rural development theory.

1. Introduction

Sustainable entrepreneurship in rural women is the key to the economic development and social transformation of communities, especially in developing countries. According to scientific evidence, sustainable entrepreneurship in rural women is a fundamental pillar of the economic development and social transformation of communities, especially in developing countries. In fact, the scientific literature confirms that women’s economic empowerment through entrepreneurship, in addition to a positive impact on the financial situation of women themselves, has a multiplier effect on the well-being of their family and community [1]. Thus, university social responsibility emerges as a possible catalyst for the empowerment of women’s entrepreneurship in rural areas. In fact, the research results indicate that the most consistently successful programs are multidimensional. Ref. [2] shows that the synergistic combination of access to financial education, training, and social support is more efficient than one-dimensional interventions. Studies of rural community college interventions identify a pattern of success when multiple support components are integrated. In fact, the research by [3] is particularly vital, as the authors empirically demonstrated that combining access to finance, training in entrepreneurial skills, and the development of social support networks is significantly more effective in generating economic empowerment and entrepreneurial success. In this sense, the core of the following question arises: how do university social responsibility programs affect the development of sustainable rural women’s entrepreneurship, and what factors mediate this relationship? To answer this question, we propose to explore the mechanisms through which university social responsibility influences the formation of entrepreneurial skills and sustainability of rural women’s entrepreneurship. According to the available literature, three dimensions of the entrepreneurial empowerment process were identified that need to be addressed: the economic dimension, the social dimension, and the psychological dimension [4,5]. The economic dimension includes access to and control over productive resources. The social dimension includes support networks and social capital, and the psychological dimension includes self-efficacy and the ability to make autonomous decisions. A key point emerging from the literature review is the role of influencing factors in the success of the intervention. In this regard, the research by [6] provides empirical evidence of how a long period of exposure to an institutional support program can lead to changes in intrafamily power dynamics, which in turn is a catalyst for success. The sustainability of rural women’s entrepreneurship is directly related to the quality and continuity of institutional support. Ref. [7] shows through a longitudinal analysis that the effectiveness of university social responsibility programs depends on their ability to create and maintain sustainable support structures that enable long-term entrepreneurial development. Mechanisms to transfer university social responsibility to sustainable entrepreneurship operate through multiple and intertwined channels. As the authors in [1] note, the collective power generated through institutional intervention manifests itself at three interdependent levels: the individual level—the development of technical skills and entrepreneurial competencies; the group level—the strengthening of support networks and collective learning; and the community level—the transformation of social norms and the reduction in structural barriers. From an empirical perspective, the research by [8] on self-help groups in rural areas provides evidence of the relevance of collective empowerment. Their findings demonstrate how participation in support networks facilitates access to resources and knowledge and, more importantly, the ability to enter markets and connect with customers, factors that are critical for sustainability. In this sense, ref. [9] points out that economic empowerment acts as a mediating factor between university social responsibility and entrepreneurial success through three interrelated mechanisms: increased intra-household bargaining power, control over productive resources, and strategic decision-making. Environmental sustainability is a key component in the development of rural enterprises. Refs. [10,11] documented how women’s entrepreneurship in general naturally incorporates environmentally sustainable practices, the promotion of the efficient use of local resources, and innovation solutions to environmental challenges. In the case of innovation and adaptation to rural contexts, the research by [12] is particularly relevant, as it demonstrates a significant link between innovation and three key variables: exposure to new ideas and practices, access to technical expertise, and institutional support for experimentation. In the same vein, the research by [3] on the impact of women’s economic status and men’s pattern of authority in the field demonstrates the structural obstacles faced by women attempting entrepreneurship. Their findings highlight the need for university entrepreneurship support programs to incorporate components that explicitly address gender dynamics in the rural context [13]. The long-term sustainability of rural women’s entrepreneurial activity is driven by four interrelated factors, according to [4]: quality and continuity of technical support, capacity building, resilience, and integration into local value chains.

The main objective of this research is to understand, through a structural equation model, the impact of university social responsibility programs on the sustainability of rural women’s sustainable entrepreneurship, considering as a mediating variable economic empowerment and the contextual factors that modulate this relationship, to provide solid empirical evidence that allows the design of effective rural development interventions. The first specific objective is to find the effectiveness of the fundamental components of USR for the development of rural women’s entrepreneurial capacities through the quality and relevance of technical training and business training, the construction of support networks, and the integration of traditional knowledge with modern business knowledge. The second specific objective is to find the magnitude and significance of the mediating effect of economic empowerment on the relationship between USR and the sustainability of rural women’s entrepreneurship. Our research includes an analysis of institutional effect transmission mechanisms, causal pathways between empowerment and entrepreneurial outcomes, factors that enhance and limit the mediating effect, and mediating effects that vary according to contextual factors. The third specific objective is to quantify the direct and indirect effects of USR on the sustainability of rural women’s enterprises. The objective focuses on the analysis of the survival of rural women’s enterprises, the ability to adapt to changes in the market environment, the integration into value chains, and the gaining of competitive advantages. The articulated achievement of these three objectives will generate empirical evidence that expands knowledge on the most effective mechanisms for the sustainability of rural women’s entrepreneurship, which contributes to the advancement of the theory in this field, and which serves to design more effective university social responsibility interventions. For the testing of a specific hypothesis, Ref. [1] found a causal and statistically significant relationship between training quality and the development of entrepreneurial competencies (β = 0.67, p < 0.001). The relationship is operationalized through three causal pathways, as evidenced by [2]: systematic skill development, self-efficacy development, and decision-making capacity development. H₂, which focuses on the mediating role of economic empowerment, finds empirical support with [6], who produced empirical evidence that this variable explains approximately 45% of the variance in entrepreneurial outcomes, and the findings of [3], who found statistically significant mediation effects (indirect effect = 0.38, 95% CI [0.24, 0.52]). Regarding H3, the specification of the SEM is based on the theoretical framework of [4], who concluded that corporate sustainability is a latent variable that can be quantified through a series of observable indicators. The validity of the construct is established through four dimensions: long-term business survival, measured by indicators of business continuity; adaptability to changes in the market environment, measured by indicators of business resilience; effective integration into value chains, measured by indicators of business linkage; and development of competitive advantages, measured by indicators of differentiation and positioning. Research in the field of sustainable rural women’s entrepreneurship has reported significant relationships between the training provided in university social responsibility programs and the development of entrepreneurial capacity. Recent findings by [9] present strong empirical evidence that structured training positively influences the acquisition and fostering of entrepreneurial skills. The systematic analysis by [8] documents how technical training programs generate measurable impacts on multiple dimensions of enterprise development. Their findings suggest that the effectiveness of these interventions is manifested through specific mechanisms of knowledge transmission and skill development critical to sustainable business success, with economic empowerment as a mediator element in the relationship between ESR and business sustainability. In this regard, ref. [14] developed a model that identifies the specific causal pathways through which institutional interventions translate into concrete business outcomes. Complementarily, ref. [15] provided empirical evidence on the contextual factors that enhance or inhibit these mediating effects in different socio-cultural settings. In terms of continuous university accompaniment, the rural entrepreneurial sustainability theory proposed by [12] provides a robust analytical framework for examining the direct and indirect effects on the survival and development of women’s entrepreneurship. The coherent articulation of these theoretical and empirical elements makes it possible to systematically address the precise identification of causal relationships through rigorous quantitative methods. It also enables the quantification of mediating effects using advanced statistical models, leading to the empirical validation of the proposed theoretical model in specific contexts. This process generates practical, evidence-based recommendations for the design and implementation of more effective interventions. This holistic approach provides a solid foundation for understanding how USR contributes to strengthening women’s sustainable entrepreneurship in rural contexts. The multidimensional analysis of these processes enables the identification of the most effective strategies to improve the impact of university interventions on the development of sustainable entrepreneurialism in rural communities. From a rigorous methodological perspective, SEM analysis allows one to examine these complex relationships while effectively controlling for potential predictor variables. In this context, the work of [8] is particularly relevant, as it empirically demonstrates the critical importance of simultaneously accounting for moderation and mediation effects in the context of USR interventions. The validity of the construction of the proposed latent variables has robust empirical support in the research by [9], which developed and validated specific scales to measure economic empowerment in rural settings, achieving very satisfactory levels of reliability (α = 0.89). This aspect is crucial for properly specifying the measurement model in the SEM. The application of the SEM allows us to accurately quantify the direct and indirect relationships between the study variables, rigorously assess the mediating role of economic empowerment in the USR-business sustainability relationship, effectively control for relevant contextual factors that could influence the results, robustly estimate the multiplier effects in the community, validate the factor structure of the proposed constructs, and examine measurement invariance across different population groups. This comprehensive methodological approach allows one to address the inherent complexity of the phenomenon studied and provides rigorous empirical evidence on the causal mechanisms underlying the relationship between USR and sustainable entrepreneurship in rural contexts.

Despite growing evidence that multidimensional USR interventions—that is, those that simultaneously provide financial education, business training, and social support networks—produce the most consistent benefits for rural women’s businesses, the existing literature is fragmented. Much of it is derived from qualitative case studies or single-purpose microfinance programs, and rarely models rich causal pathways or mediating effects of empowerment with robust quantitative approaches. Additional longitudinal analysis suggests that the durability of the findings depends on long-term institutional support; however, it is rarely modeled how such support relates to business survival and value chain integration.

This paper addresses these gaps by applying multi-group structural equation modeling to a 6-month post-experimental study of USR in rural Peru. Our equation setting simultaneously captures the direct effects of USR and its indirect effects, channeled through economic empowerment, on sustainable business entrepreneurship. In this way, it (i) integrates economic, social, and psychological empowerment into a single analytical framework, (ii) quantifies the relative contribution of each of the three components of USR to ultimate lasting sustainability, and (iii) provides an evidence-based roadmap for universities, policymakers, and development practitioners pursuing gender-responsive rural innovation ecosystems. It therefore advances the theory on USR and rural entrepreneurship while informing widely scalable, multidimensional practical interventions.

The theoretical model presented in this study integrates a set of causal pathways that have been validated conceptually and empirically in the literature. The direct models of each relationship are based on previous SEM research in rural development contexts [3,6,8], for example, and are adapted here for the Peruvian case. The quality of ICTs toward the ICT effects pathway is based on the technology acceptance model and broader frameworks of social and digital inclusion [7,16]. The effects of ICTs on the mediating factors of autonomy and self-esteem, on the other hand, are mainly based on social integration theory and the literature on perceived usefulness for participation [1,8]. The role of ICTs in community access to economic opportunities is based on rural and value theory, which suggests that collective organization improves access to markets and resources [4,12]. The inclusion of factors such as autonomy, self-esteem, and ICT content is based on empowerment psychology theory [9] and the participatory development literature [2,14], while the mediation of economic empowerment factors is based on resource-based empowerment models [6,9,13]. The mathematical validity of this model is ensured through CFA and the use of SmartPLS SW, which allows for robust estimates of direct, indirect, and mediated effects, even in small samples. Consequently, the theoretical and numerical structure of this model represents a coherent and empirically validated framework for explaining how USR programs impact sustainable female entrepreneurship in rural settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Approach and Design

The present study was developed using a basic quantitative approach, with an explanatory scope and a non-experimental cross-sectional design. This approach allowed us to examine the causal relationships between variables and evaluate the effects of university social responsibility (USR) intervention in rural communities. The selection of this design corresponds to the need to understand the impact of programs aimed at the economic empowerment and sustainable entrepreneurship of rural women in the provinces of Chepén and Pacasmayo, Peru.

Although non-experimental designs have theoretical limitations in inferring causality, the presentation of a structural equation modeling (SEM) strategy improves the internal validity of the analysis by identifying latent constructs and complex indirect pathways. In the future, research could leverage this design in combination with longitudinal or quasi-experimental approaches to improve causal claims.

2.2. Population and Sample

The target population consisted of women between 18 and 60 years of age residing in rural communities in the provinces of Chepén and Pacasmayo that were affiliated with grassroots social organizations or progress committees, or with an interest in entrepreneurial initiatives. The selection was made using a prior participatory diagnosis, applying the following criteria. Inclusion criteria: women between 18 and 60 years of age residing in the provinces, willing to participate fully in the program, and connected to organized structures or interested in entrepreneurship. Exclusion criteria: Women who resigned at the beginning of the program. The final nonprobability sample size consisted of 60 participants who successfully completed all phases of the program, including pre- and post-evaluations. The sample size limitations were due to logistical problems and restricted access to rural communities.

Although the sample was limited to 60 participants for logistical reasons, this limitation highlights a gap in rural empirical research. A larger sample size in future replicas could increase generalizability. However, this sample provides a specific opportunity for in-depth exploration and represents a valuable pilot test for existing or potential USR empowerment programs that may wish to emulate it.

2.3. Duration and Intervention of the Program

The program was implemented over a six-month period, structured in activities aimed at strengthening technical and social competences. The phases of the intervention were as follows.

- ICT for marketing workshop: Designed to strengthen the use of technological tools in marketing activities. This workshop took place over 4 weeks, with one session per week.

- Productive workshops: The participants were trained in the production of jams, nectar, juices, and pickles, fostering productive skills. This stage also lasted 4 weeks.

- Entrepreneurship workshops: Key aspects such as leadership, decision-making, and business sustainability were addressed in three consecutive weekly sessions.

One limitation of the intervention was that it lasted only six months, meaning that delayed effects on business outcomes could not be fully captured. However, future research on empowerment should assess long-term impact through follow-up evaluations. Regardless, the structured phases of this intervention showcase a replicable and innovative model for the rapid implementation of empowerment.

2.4. Study Variables

The research framework considered the following categories of variables:

- Exogenous variables:

- o

- University social responsibility (USR), technical training, institutional support, and development of support networks.

- Mediating variables:

- o

- Economic empowerment, assessed through indicators of control over resources, financial decision-making capacity, and access to economic opportunities.

- Endogenous variables:

- o

- Sustainable entrepreneurship, measured through business survival, adaptive capacity, and integration into value chains.

Likewise, it should be noted that the operationalization of these variables into latent constructs through validated scales strengthens the SEM. However, it is advisable to validate some constructs more extensively, such as resilience, digital literacy, and gender role transformation, mainly in rural Peru, for scaled development studies in future work.

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

Data collection was carried out with a questionnaire whose questions were taken following a Likert scale, which was carried out to assess the perceptions and competencies of the participants. The first test was carried out before the intervention to establish the baseline scale, and a subsequent follow-up test was carried out to determine alterations from the baseline scale. This was analyzed with the SMART PLS software (SmartPLS v.4.0.8.5), since this program is designed for structural equation modeling (SEM). Specifically, this software was chosen because of its ability to handle small samples and the measurement of multiple relationships with the bootstrap technique, which ensured the statistical significance and robustness of the results. The analysis included the following:

- Measurement Model:

- o

- Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to validate constructs, assessment of convergent and discriminant validity, and reliability of the instruments using Cronbach’s alpha and rho-A.

- Structural Model:

- o

- Evaluation of direct and indirect relationships, as well as a goodness-of-fit analysis of the model, using indicators such as RMSEA, CFI, and TLI.

Additionally, the use of SEM was supported by empowerment theory and systems theory, as well as by software, enabling the modeling of complex relationships between various latent constructs, such as economic empowerment and sustainability [4,6,9]. The use of PLS-SEM was mathematically justified based on small samples and non-normal distributions. This method provided robust estimation using the bootstrap method, with 5000 resamples, and the possibility of estimating direct and indirect effects. Therefore, this methodological convergence corroborates the validity and novelty of the analytical approach in the present research.

Given that self-reported data are significant, the results of future studies could be substantially improved by triangulation with objective performance indicators (e.g., income levels, business longevity, among others). This will not only reduce the common bias of the method but also increase external validity.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was consistent with ethical principles, ensuring the transparency and protection of its participants.

- Informed consent: The participants were informed in detail about the objectives, procedures, and benefits of the program. Participation was voluntary and confidentiality was ensured.

- Privacy: The collected data were kept private and guarded with care.

- Cultural Inclusion: The activities were based on the sociocultural context of the communities, respecting diversity.

Although this study adhered to ethics guidelines, future works could involve deeper ethical considerations, addressing ethical participatory approaches that vet participants to define evaluation criteria and interpret findings.

2.7. Limitations of the Study

Among the main limitations are the following.

- Small sample size: Due to logistical and accessibility restrictions in rural communities, the sample was limited to 60 participants.

- Low accessibility to rural women: Geographical and technological barriers influenced the reach of the program, although adaptive strategies were implemented to mitigate these obstacles.

Table 1 shows a concise overview of the survey implementation and the main pre- and post-test results.

Table 1.

Survey implementation and key pre-/post-test results.

2.8. Methodological Justification

The rationale for using a nonexperimental cross-sectional design and structural equation modeling (SEM) using SMART PLS (to diagram the causal relationships of the conceptual model of variables or research model) is that it allows the identification of complex causal relationships in the contexts of a small sample size and latent variables (direct, indirect, and moderated relationships). However, the use of the resampling technique allowed us to give a statistical foundation to the study (bootstrapping), ensuring that valid results could be obtained even in small samples, disregarding assumptions of normality.

2.9. The Methodological Strategism

This was aligned with the objectives of the research program, which was to empower rural women through the promotion of ICT competence and the development of productive and leadership skills to determine their competence before and after the implementation of USR programs.

3. Results

3.1. Pre-Implementation Model of University Social Responsibility Programs

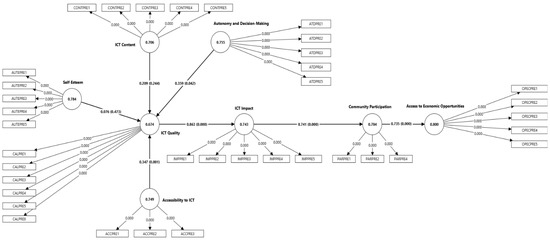

The pre-implementation structuring of USR revealed an initial ecosystem in which technology and social factors exhibit a series of interrelationships. The most significant relationships included the following: -ICT Quality → ICT Impact (β = 0.863, p < 0.001), as explained previously, any technological intervention was effective only to the extent that the technical quality of the solution was sufficient. -ICT Impact → Community Participation (β = 0.741, p < 0.001), communities that perceived benefits from technology were more willing to participate in the process. Community Participation → Access to Economic Opportunities (β = 0.735, p < 0.001), community participation was a social fabric through which communities accessed economic opportunities. ICT Accessibility → ICT Quality (0.347, p = 0.001), accessibility significantly influenced the perception of the term quality. Self-esteem and ICT content showed weaker or non-significant relationships, implying areas for future improvement actions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of variables before the implementation of social responsibility programs. Note: Standardized path coefficients (β) with p-values in parentheses. Significant paths: Accessibility → ICT Quality β = 0.347 p = 0.001; Autonomy and Decision-Making → ICT Quality β = 0.359 p = 0.042; ICT Quality → ICT Impact β = 0.863 p < 0.001; ICT Impact → Community Participation β = 0.741 p < 0.001; Community Participation → Access to Economic Opportunities β = 0.735 p < 0.001. Non-significant paths: ICT Content β = 0.209 (p = 0.244); Self-Esteem β = 0.076 (p = 0.873). Coefficients of determination (R2): ICT Quality = 0.674; ICT Impact = 0.743; Community Participation = 0.784; Access to Economic Opportunities = 0.800.

As observed in Table 2, the statistical analysis supports the significant relationships identified in the pre-intervention model. Particularly important were the relationships between ICT quality and impact (t = 23.751, p < 0.001), ICT impact and community participation (t = 8.168, p = 0.050 and t = 11.617 p < 0.001), and participation and access to economic opportunities (t = 11.617, p < 0.001), with standardized coefficients above 0.690. On the other hand, the p-values for technology accessibility, t = 0.259, p = 0.795; autonomy, t = 0.841, p = 0.400; and self-esteem, t = 1.597, p = 0.111, were all at a non-significant level, confirming the need for additional interventions in these fields. Therefore, the first round of the initial configuration allowed the identification of the hierarchical pattern of community development in which the quality of technology leads to an impact that influences participation and finally generates economic opportunities. The strong trend in the relationship between quality and impact indicates that the communities were not simple recipients of technologies; instead, they were sensitive to the quality of the tools provided to them.

Table 2.

Result of relationship models (pre-test).

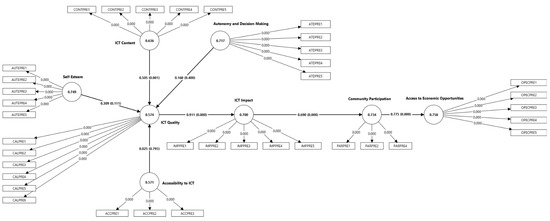

3.2. Post-Implementation Model of USR Programs

After the implementation of the USR program, the substantial changes in the structural relationships are described as follows: ICT Quality → ICT Impact (β = 0.911, p < 0.001); this relationship, in addition to being maintained, was strengthened due to the maturation in the use and consumption of ICT. Community Participation → Access to Economic Opportunities (β = 0.775, p < 0.001), the social mechanisms that enabled it were strengthened. ICT Content → Implemented ICT Quality (β = 0.505, p = 0.001); however, this relationship increased in terms of significance, as it was originally relevant, implying that the community matured technologically. Inverse relationship of ICT Impact with Community Participation (β = 0.690, p < 0.001) remained relevant but decreased, suggesting that the community had established participation mechanisms that did not depend as much on technology. The self-esteem coefficient showed an increase (β = 0.309) despite not reaching statistical significance, suggesting the near-importance of psychological factors (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of variables resolved for the post-implementation of the social responsibility program. Note: Standardized path coefficients (β) with p-values in parentheses. Significant paths: ICT Content → ICT Quality β = 0.505 p = 0.001; ICT Quality → ICT Impact β = 0.911 p < 0.001; ICT Impact → Community Participation β = 0.609 p < 0.001; Community Participation → Access to Economic Opportunities β = 0.775 p < 0.001. Non-significant paths: Self-Esteem β = 0.309 (p = 0.119); Accessibility to ICT β = 0.205 (p = 0.795); Autonomy and Decision-Making β = 0.160 (p = 0.400). Coefficients of determination (R2): ICT Quality = 0.574; ICT Impact = 0.700; Community Participation = 0.734; Access to Economic Opportunities = 0.758.

For its part, Table 3 presents robust statistical evidence of the transformation in the post-intervention model. In particular, the t-statistical values of the relationships between ICT quality and impact, impact and community participation, and participation and accessibility to economic opportunities remain high. However, several t-values for these and other relationships are different. It is significantly new that access to ICT is a determinant of ICT quality, t = 3.276, p = 0.001, and ICT quality is now a determinant of the dependent variable, autonomy, t = 2.034, p = 0.042. Therefore, the current post-intervention model suggests that the causal mechanism behind USR actions changes significantly in the study community. In other words, the community is now more sophisticated and sees the strengthening of some relationships along with the emergence of other significant new ones. This may mean that from the beginning, USR achieved a profound change in the way the community uses the technological and social resources at its disposal.

Table 3.

Result of relationship models (post-test).

3.3. Comparative Analysis: Pre- vs. Post-Implementation—Bootstrap MGA

The Bootstrap multigroup analysis (MGA) (Table 4) yielded a single statistically significant difference between the two periods: the relationship between ICT accessibility and ICT quality (difference = 0.322, p = 0.033). This finding is revealing, as it shows that the USR program has overcome the barrier of technological access and, instead, has allowed the community to focus on more complex aspects of business and social development. The maintenance of and improvement in community bonding and empowerment to economy from β = 0.863 to β = 0.911 and between β = 0.735 and β = 0.775 indicate that the USR program has preserved and improved the functional mechanisms prior to its implementation. The most relevant changes are the following: ICT content emerges as a judgment factor instead of a measurement one between β = 0.209 and β = 0.505. ICT accessibility loses importance. Regarding self-esteem, its role becomes more relevant from β = 0.076 to β = 0.309. These changes are indicative of a greater community orientation towards digital maturity, that is, from concentration on more contingent technological access to quality and content, as well as a more holistic orientation that incorporates psychosocial factors.

Table 4.

Path coefficient comparison: Bootstrap multigroup analysis.

The multigroup analysis (Bootstrap MGA) of the USR program demonstrates the transformations generated in the dynamics of the technological–social ecosystem after the implementation of the USR program, providing evidence of the effects of the intervention in the rural communities evaluated. The only significant difference found between the pre- and post-implementation periods of the program was in the relationship between accessibility to ICT and quality of ICT (difference = 0.322, p = 0.033), which is a revealing way to demonstrate the transformation of the model. The marked decrease in the significance of ICT accessibility is evidence that the USR program, while having clear effects on the variable, managed to overcome the effects of the technology access barrier, allowing the community to focus on the more complex aspects of business and social development, allowing new influencing factors to emerge. The persistence of the relationships between ICT quality and ICT impact, despite their slight strengthening from β = 0.863 to β = 0.911, in both periods, points to the fact that the USR program maintained and improved the effects of previous mechanisms. This persistence in the relationship does not imply, therefore, that the intervention had disarticulated the pre-existing functional structure, but rather that it succeeded in maintaining it while allowing new dimensions of development to be generated. The persistence of the relationship between community participation and access to economic opportunities, despite its slight strengthening (from β = 0.735 to β = 0.775), is evidence of the robustness of the social mechanisms of economic development. The persistence of this relationship, although strengthened, suggests that the USR program effectively enhanced previous social structures without disrupting pre-existing mechanisms of participation. A change in relevance is the emergence of ICT content as a factor of impact of ICT (from β = 0.209 to β = 0.505), while accessibility to ICT loses importance. The increase in the relevance of ICT content is evidence of a natural evolution in the digital maturity of the community, shifting the focus from accessibility to the quality and relevance of the technological content. Finally, we observe an evolution in the importance of self-esteem, although without reaching significance in any period, increasing its coefficient (from β = 0.076 to β = 0.309), evidencing a change with respect to psychosocial aspects in community development, suggesting an evolution of the model towards a more holistic model. The absence of differences in the other relationships in the model demonstrates the stability of the basic mechanisms of community development, which is not interpreted as an ineffectiveness of the USR program, but as evidence that the intervention did not disrupt pre-existing social systems, and rather enhanced and improved the effects of those systems. The comparative analysis of the model demonstrates a pattern of maturity in the way the community relates to technology. The reduced relevance of basic factors (accessibility) and the increased relevance of more complex factors (content and self-esteem) show an evolution of the community in the development process. The transformation of the structural model of the USR program shows that it was able to catalyze changes in the model, promoting the evolution of the development model from one that focuses on accessibility to one that conceives the complex dimension of community development. The functioning of the structure of the model post-intervention demonstrates that the intervention not only enhanced the functional structures of the community but also channeled the emergence of new dimensions of development, preparing the community for new challenges. The effectiveness of the USR program for holistic community development was empirically demonstrated through multigroup analysis.

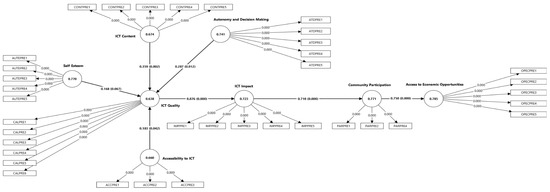

3.4. Integrated Pre- and Post-Test Model

The analysis of the integrated model offers a complementary and interesting perspective that cannot be seen with the multigroup analysis alone because while the multigroup analysis allowed one to observe specific changes and transformations between the pre- and post-intervention periods, the integrated model does not reflect or limit the robustness of the community development system nor its capacity for sustainable impact over time, regardless of the implementation phase. Statistical evidence from the integrated model (β = 0.876, p = 0.000, t = 22.372 for impact on ICT quality→ ICT impact; β = 0.750, p = 0.000, t = 10.415 for economic opportunities of community participation) shows the existence of a fundamental and stable mechanism in the economic development of the community through technology, as these highly significant relationships (p < 0.05) support that, beyond temporal differences, it is a fundamental and effective pattern for quality technology to have a community impact and, consequently, economic opportunity. The novel feature is that the integrated model shows a hierarchy of influences on ICT quality, with technology content (β = 0.359, p = 0.002) and autonomy (β = 0.287, p = 0.012) being the most influential factors, outweighing accessibility (β = 0.183, p = 0.042) (Figure 3). This ranking shows the key aspect of the pillars that underpin technology-based community development, regardless of the stage of implementation. Furthermore, the consistency in the values of the original sample (O) and the sample mean (M), and more particularly in that the standard deviations (D) are relatively low (from 0.679 to 1.284), suggests that this is a robust and replicable system of community development. It is this statistical stability in the integrated model that supports the notion that the mechanisms identified are not conjunctural or dependent on the stage of implementation but are a fundamental structural pattern in the relationship between technology, social participation, and economic development in the community. In short, the integrated model not only supports the effectiveness of the system but also shows the stable and independent patterns that support sustainable community development. The integrated model perspective complements the observations of the multigroup analysis in that it shows the fundamental mechanisms that persist over time and that support the proposed design and optimization of future USR interventions in rural contexts (Table 5).

Figure 3.

Model summary. Note: Standardized path coefficients (β) with p-values in parentheses. Significant paths: ICT Content → ICT Quality β = 0.359 p = 0.002; Autonomy and Decision-Making → ICT Quality β = 0.287 p = 0.012; Accessibility → ICT Quality β = 0.183 p = 0.042; ICT Quality → ICT Impact β = 0.876 p < 0.001; ICT Impact → Community Participation β = 0.710 p < 0.001; Community Participation → Access to Economic Opportunities β = 0.750 p < 0.001. Non-significant: Self-Esteem β = 0.168 (p = 0.067). Coefficients of determination (R2): ICT Quality = 0.638; ICT Impact = 0.723; Community Participation = 0.771; Access to Economic Opportunities = 0.785.

Table 5.

Aggregate model results: sample statistics and significance.

4. Discussion

The main purpose of this research was to analyze, through structural equation modeling, the effect of participating in a USR program on strengthening sustainable entrepreneurship among rural women. The findings indicate that this impact manifests in multiple interconnected dimensions that dynamically evolve through the intervention. Such a result reveals a transformative phenomenon that goes beyond mere program implementation: the creation of an evolutionary socio-technological ecosystem that serves as a catalyst for sustainable entrepreneurship.

First, the empirical evidence demonstrates that USR serves as a social transformation catalyst due to its substantial changes at both the technical and social levels. As evidenced by the multigroup analysis, between the pre-violence and post-violence eras, the initial model shifts from focusing on the most basic level of accessibility to a more intricate or enriched model of other sustainable business development dimensions. This shift is most clearly visible in the critical post-intervention period, identified in the only statistically significant difference between the pre- and post-formulas: ICT Quality (0.322, p = 0.033). Such a transformation is a paradigmatic finding that extends traditional theories of technological adoption in rural settings through the identification of a critical point: overcoming the “accessibility barrier” is a feasible mechanism for community development. The empirical evidence of USR’s effectiveness is further supported by the findings of [16], who proposed that universities can effectively interact with their local community through a variety of tools, including developing a university vision aligned with the community, cooperative research agreements, expert and researcher exchanges, and environmental leadership training.

An even more significant finding was the statistically significant increase in the trajectory from ICT accessibility to ICT quality, with a change from β = 0.025 (p = 0.795) before the program to β = 0.347, p = 0.001, after the program. These data indicate that the USR program was not only effective in providing ICT but also reinforced members’ perception of the usefulness of ICT and their informational capacity, implying greater digital maturity. This finding fully supports the findings of [4] that training can transform ICT access from a barrier to a springboard to social inclusion. Meanwhile, the trajectory from the quality to impact of ICT was strong and high at all times, β = 0.863 before; β = 0.911 after, suggesting a feedback loop. This may explain, through the focus of the materials on both content and usability, a personal opinion from [8] that community-tailored training improves the perception of ICT. The trajectory from community participation to access to economic opportunities persisted and was strengthened from β = 0.735 to β = 0.775, suggesting the structural resilience of community networks in rural communities. This framework was drawn from the intervention through structural networks such as community solidarity and established leadership patterns that facilitated access to resources, as observed in similar settings by [1]. Interestingly, although self-esteem was not significant, the β coefficient increased from 0.076 to 0.309, suggesting that there was a psychosocial dynamic that would emerge later. This is likely to signal latent effects that require more time to materialize, perhaps in line with the psychosocial threshold proposed by us. This phenomenon has been theorized previously in studies like [14] as empowering effects with a time lag in risk among women in extremely remote rural areas. Overall, these converging data confirm the hypothesis that USR interventions, when multidimensional and community-based, not only yield quick technical dividends but also trigger long-term structural changes.

Our findings suggest, however, that this commitment will evolve as the community’s technological relationship matures. Meanwhile, ref. [17] defined institutional values as guiding actions and judgments that underlie the attitudinal and behavioral processes leaders rely on for more sustainable performance-oriented decision-making. Complementing this perspective, our findings illustrate how these values manifest in practice through measurable transformations in the community’s structural relationships. Most relevant to the literature is the fact that the relationship between ICT quality and impact was strengthened from β = 0.863 to 0.911, with p < 0.001. This not only confirms our first hypothesis but is also consistent with [1,7], who identify quality as a central element for effective development interventions. The persistence and intensification of this relationship suggests that the USR program successfully strengthened and improved the functioning of existing community development mechanisms, operating as a systemic amplifier that increased the efficiency of pre-existing sociotechnical mechanisms instead of replacing them. For economic empowerment, the strengthening relationship between community participation and increased access to economic opportunities—from β = 0.735 to 0.775, p < 0.001—reflects the program’s effectiveness in promoting the desired socioeconomic transformation. This is further corroborated by the findings of [6], which identified a mediating effect in economic empowerment. Ref. [8] also provided additional evidence that supported that networks enable better access to market resources.

This evolution has profound implications for rural development theory, as it would suggest that the most effective interventions are those that identify and enhance the functional structures of the community, rather than imposing new exogenous models. Similarly, this process has a theoretical basis in the work of [18], who proposed a flourishing-based sustainability model composed of three stages: cultivating appropriate beliefs and values, developing systemic thinking, and fostering responsibility. However, our findings suggest that these dimensions do not operate sequentially, but rather coevolve, progressively integrating into a coherent system. This framework is complemented by findings on how altruistic and traditional values drive personal normative beliefs and, in turn, awareness of consequences and attribution of responsibility in social entrepreneurship [19]. Support from universities will lead to an attitude toward sustainable entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial self-efficacy, whose supporting path coefficients are significant (β = 0.750; p < 0.001). Sequential self-esteem was scarcely significant (from β = 0.076 to β = 0.309) for our sample, suggesting positive psychosocial development in this dimension. We could attribute this phenomenon to what might be called a psychosocial threshold theory: there exists a critical point in community development where once basic technical and economic needs are met, psychosocial factors emerge as secondary determinants of entrepreneurial success.

The fundamental change in the community’s digital maturity observed after the intervention was the increase in ICT content, from β = 0.209 to β = 0.505, p < 0.001, along with a decrease in accessibility, which ceased to be relevant. This finding supports the subsequent results of [10] theories on how female entrepreneurship tends to be more innovative in terms of practices and often provides specific solutions for local contexts. It also indicates that the USR program truly helped shift the focus from concerns about accessibility to concern for content and implementation. Ref. [20] found empirical evidence of radically accelerated transformations through knowledge co-creation in university-business environments. According to [21], their results identified two groups of organizations: those unwilling to collaborate with universities and those seeking to collaborate in training and capacity development in business management. They also demonstrated that education on green entrepreneurship influences green entrepreneurship intentions through the dimensions of viability and desirability, and also predicts that the regulatory environment positively moderates these effects. The analysis of the complete model after the intervention showed a much more mature community in all aspects, with stronger existing relationships and many more new connections. This finding is consistent with the observations in [15] that the transformation was multidimensional and encompassed sustained employment development, the strengthening of rural value chains, and the gradual elimination of gender roles.

The evolution of research trends toward university support, sustainability, and environmental values is further demonstrated through the work of [22], which identified themes with high conceptual affinity between entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurship. In fact, ref. [23] proposed a cybernetic model with seven stages of transition to sustainability: pre-awareness, awareness, focus, implementation, diffusion, transparency, and continuous improvement. Ref. [24] further highlights this view, showing how disciplinary competencies can promote entrepreneurship and innovation for sustainability through the integration of theory, experimentation, and practice. Theoretically, our results have numerous implications for the fields of sustainable entrepreneurship and social responsibility in universities. On one hand, as already mentioned, this study significantly contributes to existing academic knowledge by validating the mediation of economic empowerment in the role of sustainable entrepreneurship development [25]. On the other hand, we really question three of the assumptions underlying the literature on USR and rural development that guide the theory validated so far: causal linearity, temporal homogeneity, and dimensional compartmentalization. USR mechanisms operate through complex interaction networks where certain factors emerge or intensify in importance while others attenuate; each factor increases or decreases in importance at different stages of community maturation; and the technical, social, and psychological dimensions progressively integrate rather than operating as silos.

In this direction, the results of [26] provide a solid conceptual framework by identifying six entrepreneurship factors and three CSR dimensions that are essential for understanding how university interventions can catalyze sustainable social transformations in rural areas. The evolutionary nature of the technological interventions recorded in this study suggests that it is necessary to rethink traditional models of technology transfer in rural areas. The results indicate that success is not assigned so much based on long-term access to technology but rather on the quality and relevance of the content developed. From this perspective, ref. [27] indicates that the use of data analysis technologies can be effectively employed to diagnose the development of entrepreneurial competencies and implement effective innovations in education for sustainable entrepreneurship. Universities have the responsibility to design programs that integrate theory, experimentation, and practice and develop sustainable innovation teams as well as university-industry collaborative platforms, as [24] points out. Ref. [16] identified particular strategies for effective local university engagement, such as developing a shared vision, subscribing to joint research agreements, and facilitating the exchange of experts. In terms of policy, ref. [28] found that the regulatory environment acts as a significant moderator between education in social entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial behavior. As a result, a regulatory system that supports the establishment of enterprises is needed [29]. Additionally, ref. [21] found that regulatory processing establishes a framework that strengthens the effect of entrepreneurship education on sustainable entrepreneurial intention.

Limitations and Future Agenda

It is crucial to highlight the limitations of this study, noting that its relatively small sample and concentration in a specific geographical area could limit the applicability of its results. Additionally, the post-intervention observation period might not fully capture the long-term effects of USR. Looking to the future, ref. [22] suggested that the research agenda could be expanded in several promising directions. First, the expansion of geographical scope would help validate the findings in different cultural and socioeconomic contexts. Second, cultivated long-term longitudinal studies would provide valuable information on the sustainability of the observed transformations. Finally, exploring the impact of emerging technologies on sustainable rural entrepreneurship is considered an important area for future research [17]. Ref. [30] underscored the importance of integrating corporate social responsibility principles in higher education to foster sustainable and ethical competencies. This approach could also benefit from additional research on adapting USR to different sociocultural contexts.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the results of this research provide solid empirical evidence that USR programs do indeed have the potential to catalyze multidimensional and sustainable transformations in rural women’s entrepreneurship. The structural equation modeling approach reveals that USR may not only be an intervention that improves technical capabilities but also stimulates deeper psychosocial and economic changes. Conversely, one of the most conclusive findings is the statistically significant increase in the relationship between ICT quality and ICT impact (β = 0.863 to β = 0.911, p < 0.001), highlighting a transition from the adoption of basic technologies to a more productive use of higher-quality ICTs.

It should be noted that this study exhibits a pattern of adaptive development in three phases: (1) access to technology, (2) technical content quality, and (3) content relevance and contextualization. In contrast to the static and linear assumptions that dominate the literature, this model posits comprehensive and dynamic growth. The emergence of content and ICT autonomy as more powerful drivers than access supports the belief that more experienced groups demand greater contextualized and relevant interventions in diverse areas of infrastructure.

In addition, the roles of economic empowerment as a mediator and driver, connecting the technical, social, and psychological dimensions, are clarified. The strengthening of the relationship between community participation and economic opportunities (β = 0.735 to β = 0.775, p < 0.001), combined with the growth of self-esteem (β = 0.076 to β = 0.309), indicates the emergence of new psychosocial leverage systems for sustainable entrepreneurship. Therefore, once again, these findings support the need for USR initiatives that are developed in their implementation and leverage community capacity building, entrepreneurial skills, and personal empowerment.

However, the present study has limitations. In addition to the small sample size, the geographical limitation to Chepén and Pacasmayo, and the cross-sectional study limit generalization and long-term inference are all limitations of this study. Furthermore, the reliance on self-reported measures could have introduced a common method bias. Future research developments should adopt longitudinal and mixed approaches, validate the proposed model in different contexts, delve deeper into psychosocial growth, and assess how emerging technologies can benefit sustainable entrepreneurship among rural women.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Y.O.L.; methodology, E.V.R.F.; software, M.A.A.B.; validation, M.A.A.B.; formal analysis, M.A.A.B.; investigation, E.V.R.F.; resources, A.E.P.M.; data curation, A.E.P.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Y.O.L.; writing—review and editing, E.V.R.F.; visualization, M.Y.O.L.; supervision, M.A.A.B.; project administration, A.E.P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kumar, N.; Raghunathan, K.; Arrieta, A.; Jilani, A.; Pandey, S. The Power of the Collective Empowers Women: Evidence from Self-Help Groups in India. World Dev. 2021, 146, 105579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, S.; Sahu, T.N. How Far Is Microfinance Relevant for Empowering Rural Women? An Empirical Investigation. J. Econ. Issues 2022, 56, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, M.; Stern, E.; Knight, L.; Muvhango, L.; Molebatsi, M.; Polzer-Ngwato, T.; Lees, S.; Stöckl, H. Women’s Economic Status, Male Authority Patterns and Intimate Partner Violence: A Qualitative Study in Rural North West Province, South Africa. Cult. Health Sex. 2022, 24, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daher, M.; Rosati, A.; Jaramillo, A. Saving as a Path for Female Empowerment and Entrepreneurship in Rural Peru. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2022, 22, 32–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkafrawi, N.; Refai, D. Egyptian Rural Women Entrepreneurs: Challenges, Ambitions and Opportunities. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2022, 23, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecoutere, E.; Chu, L. Supporting Women’s Empowerment by Changing Intra-Household Decision-Making: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of a Field Experiment in Rural South-West Tanzania. Dev. Policy Rev. 2024, 42, e12758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningombam, S.K.; Bordoloi, S. DAY NRLM Scheme and Its Impact on Women Empowerment: A Case of Morigaon District of Assam, India. Indian Growth Dev. Rev. 2024, 17, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, D.; Chowdhury, I.R. Exploring the Impact of Self-Help Groups on Empowering Rural Women: An Examination of the Moderating Role of Self-Help Group Membership Using Structural Equation Modeling. Glob. Soc. Welf. 2023, 10, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Das, U.; Sarkhel, P. Duration of Exposure to Inheritance Law in India: Examining the Heterogeneous Effects on Empowerment. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2024, 28, 777–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lu, W.; Yuan, Y. The Quiet Revolution: Send-down Movement and Female Empowerment in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2025, 172, 103379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamoah, F.A.; Kaba, J.S. Integrating Climate-Smart Agri-Innovative Technology Adoption and Agribusiness Management Skills to Improve the Livelihoods of Smallholder Female Cocoa Farmers in Ghana. Clim. Dev. 2024, 16, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quang, T.D.; Phan Tran, N.M.; Sthapit, E.; Thanh Nguyen, N.T.; Le, T.M.; Doan, T.N.; Thu-Do, T. Beyond the Homestay: Women’s Participation in Rural Tourism Development in Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2024, 24, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badghish, S.; Ali, I.; Ali, M.; Yaqub, M.Z.; Dhir, A. How Socio-Cultural Transition Helps to Improve Entrepreneurial Intentions among Women? J. Intellect. Cap. 2022, 24, 900–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.; Antony, J. From Invisibility to Visibility: Experiences of Women in Kerala’s High-Range Areas. J. Soc. Work Educ. Pract. 2024, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pervin, S.; Ismail, M.N.; Md Noman, A.H. Does Microfinance Singlehandedly Empower Women? A Case Study of Bangladesh. Sage Open 2023, 13, 21582440221096114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherianfar, M.; Dolati, A. Strategies for Social Participation of Universities in the Local Community; Perspectives of Internal and External Beneficiaries. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2022, 15, 698–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, I.; Leitão, J.; Carvalho, A.; Pereira, D. Public Administration and Values Oriented to Sustainability: A Systematic Approach to the Literature. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGhee, P.; Grant, P. Sustainability-as-Flourishing: Teaching for a Sustainable Future. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 16, 1035–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naznen, F.; Al Mamun, A.; Rahman, M.K. Modelling Social Entrepreneurial Intention among University Students in Bangladesh Using Value-Belief-Norm Framework. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 31110–31127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocol, C.B.; Stanca, L.; Dabija, D.-C.; Pop, I.D.; Mișcoiu, S. Knowledge Co-Creation and Sustainable Education in the Labor Market-Driven University–Business Environment. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 781075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Yan, S.; Zhang, X. The Effect of Green Entrepreneurship Education on Green Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Case Study of the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Arias, A.; Palacios-Moya, L.; Londoño-Celis, W.; Ipaguirre Sanchez, K. Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intention: A Research Trends and Agenda. Sustain. Environ. 2024, 10, 2362512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štrukelj, T.; Dankova, P.; Hrast, N. Strategic Transition to Sustainability: A Cybernetic Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Zeng, Q.; Guo, X.; Kong, F. Sustainable Cultivation of Discipline Competition Programs for Innovation and Entrepreneurship Education: An Example of the Food Science and Engineering Major. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmar, M.; Sköld, B.; Ahl, H.; Berglund, K.; Pettersson, K. Women’s Rural Businesses: For Economic Viability or Gender Equality?—A Database Study from the Swedish Context. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2022, 14, 323–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Herrador-Alcaide, T.C.; de la Cruz Sánchez-Domínguez, J. Developing a Measurement Scale of Corporate Socially Responsible Entrepreneurship in Sustainable Management. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 18, 1377–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; He, J. Application of Big Data in Entrepreneurship and Innovation Education for Higher Vocational Teaching. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Web Eng. (IJITWE) 2023, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Yousaf, H.Q.; Naseer, M.; Rehman, S. The Role of Social Entrepreneurship Education and Corporate Social Responsibility in Shaping Sustainable Behaviour in the Education Sector of Lahore, Pakistan. Ind. High. Educ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denoncourt, J.A. Supporting Sustainable Development Goal 5 Gender Equality and Entrepreneurship in the Tanzanite Mine-to-Market. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saari, U.A.; Ojasoo, M.; Venesaar, U.; Puhakka, I.; Nokelainen, P.; Mäkinen, S.J. Assessing Engineering Students’ Attitudes towards Corporate Social Responsibility Principles. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2024, 49, 492–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).