Abstract

Despite the economic importance of Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) cheeses in Italy, little research has examined how label attributes affect price premiums. For Italian cheese producers, especially those investing in PDO certification, understanding which attributes generate premiums is crucial for sustainable business strategies. This study examined attributes displayed on 420 validated cheese labels collected across Italy in 2022, focusing on hard cheese, fresh soft cheese, and string cheese. A content analysis was conducted to identify and categorize the attributes displayed on cheese labels. Following this, the hedonic pricing method, supported by multiple linear regression analysis, was used to assess the impact of these attributes—along with brand and distribution channel—on product pricing. Our findings reveal that sustainability attributes show particularly strong effects on price premiums. PDO certification generates significant premiums prominently for hard and fresh soft cheeses, cow breed information for string cheese, while specialized retail channels create higher prices for fresh soft and string cheeses. While brand–price relationships are heterogeneous, the study provides evidence of their impact. These insights enable cheese producers, marketers, and retailers to strategically prioritize product attributes, optimize distribution channels, and make informed decisions about brand positioning to maximize value in competitive cheese markets.

1. Introduction

Cheese production in Italy has a long tradition that has led to the creation of many important commercial cheese varieties with significant added value [1,2]. According to Italian Dairy Economic Consulting (CLAL) data, Italy produced around 1.2 million tons of cheese from cow’s milk, ranking third after Germany with 2.4 million tons and France with 1.7 million tons in 2023 [3]. In 2023, the average cheese consumption per capita for Italian consumers was 21.7 kg, which was higher than that for average EU consumers (20.5 kg) [4]. The Italian Institute for Services on the Agricultural and Food Market (ISMEA) reported that in the first eight months of 2024, exports of cheese and dairy products increased significantly, by 7.6% in value and around 11.5% in volume, with very positive results in all major outlet markets [5]. The main export products were fresh cheeses (+12.8% in volume and +7.7% in value), Grana Padano and Parmigiano Reggiano (+10.4% in volume and +9.5% in value), and grated cheeses (+11.1% in volume and +9.4% in value). There was also a strong increase in cheese imports, with a rise of 8.2% in volume and 6.1% in value, particularly for fresh and semi-hard cheeses due to increased domestic consumption. Domestic demand for cheese is recovering (+1.1%), owing to the positive performance of fresh cheeses (+1.6% in volume) and spreadable-type industrial products (+3.4%), which are favored especially during the summer months due to high temperatures and convenience of use. As for the hard cheese segment, there is substantial stability in consumption (−0.2%), with prices still showing a positive trend. In addition, domestic consumption of dairy products is expected to grow at a rather slow pace over the next decade (+0.1% per year) due to increasing demand for healthy products, such as whey powder and plant-based substitute products.

This situation suggests a gradually saturating market that contributes to high competition in the cheese industry. Consequently, cheese producers and manufacturers are trying to differentiate their products from others. Their strategies range from registering products as geographical indications, or GIs (e.g., protected designation of origin, or PDO, protected geographical indication, or PGI), to implementing other food quality schemes (e.g., organic production, mountain products) [6].

PDO cheeses are cheeses with a strong connection to their origin; from milk production to cheese ripening, the PDO label assures consumers that every step of the production process occurred within the geographical boundaries designated by the designation of origin. The significance of PDO cheeses, which represent 60% of PDO and PGI products in the Italian agri-food landscape, is reflected in their production (EUR 5.5 billion), domestic consumption (EUR 9.3 billion), and export values (EUR 2.7 billion) [7]. These products are primarily purchased by quality-conscious consumers, tradition lovers, informed consumers, gourmets, and international tourists seeking high-quality ingredients and ethical and environmental values [8]. Nevertheless, due to the high number of cheese products in the Italian market, PDO cheese producers need to distinguish themselves from competitors to command premium prices. Part of their strategy involves product labeling. In such competitive environments, defining an effective product differentiation strategy is critical and has significant economic implications. For Italian cheese producers, especially those investing in PDO certification, understanding which label attributes generate price premiums is crucial for strategic decision-making and assessing the return on investment in certification and marketing efforts.

Labeling is an efficient tool to help producers communicate the quality of their products and improve consumer information about quality characteristics. In general, labels that provide consumers with information on raw materials, production processes, areas of origin, tradition, sustainability, sensory, and nutritional values can be effective marketing strategies to increase cheese sales [9,10,11,12,13]. Recent reviews confirm that origin information and sustainability labeling significantly influence consumer food choices, though origin becomes less important when combined with other quality cues [14]. Similarly, ref. [15] found that while sustainability labeling can influence purchasing behaviors, consumer understanding is often limited, and real-world effects tend to be small, with organic labeling generating the highest willingness to pay. This finding underscores the importance of examining multiple label attributes simultaneously, as their interactions may moderate individual effects on consumer valuation.

While previous research has examined consumer perceptions of cheese attributes [9,10,11], some studies have explored price determinants for other food products [16,17,18], and one study has evaluated price premiums for single-name and compound-name GI Swiss cheeses [19]. However, systematic analyses of how specific label attributes influence PDO cheese pricing in Italy remain scarce. Most existing studies either focus solely on consumer perceptions without linking them to market prices, or analyze pricing without comprehensively examining label content. This disconnect limits our understanding of which label attributes generate price premiums under actual market conditions.

Therefore, we aimed to fill this gap by investigating the attributes that suppliers present on cheese labels and how these characteristics affect prices. This study investigated three types of cheese: hard cheese, fresh soft cheese, and string cheese. The specific objectives of this study were twofold. The first objective was to explore the different attributes on the labels of selected PDO and non-PDO cheese products in the Italian market. The second objective was to assess the impact of these attributes on the sale prices of cheese products. Based on previous studies, we expected that PDO certification would create significant premiums across cheese categories, but that this effect would be moderated by complementary attributes and distribution channels.

To achieve these objectives, we employed content analysis to categorize the main and sub-dimensions displayed on the labels of selected PDO and non-PDO cheese products in the Italian market. The hedonic pricing method, which has been widely used to analyze price premiums for food product attributes [16,17,18,20,21,22,23,24,25], was also employed to assess the impact of PDO and other attributes on cheese prices. We believe our contribution lies in applying both content analysis and hedonic pricing approaches within the cheese sector. This integrated approach offers a valuable methodological framework for competitive analysis that producers and retailers can use for their strategic planning. By identifying which attributes generate statistically significant price premiums and how these vary across different cheese categories and distribution channels, our findings offer insights for product development, labeling strategies, and channel optimization.

Our findings reveal that sustainability attributes consistently generate strong price premiums across cheese categories, with animal welfare claims, organic certification, and sustainable packaging significantly influencing hard cheese pricing. PDO certification creates substantial value for hard cheese and fresh soft cheese, though its impact varies by cheese category. Distribution channels and complementary quality attributes like cow breed information play crucial roles in determining product value in competitive markets.

Literature Review on Cheese Product Attributes

Given the importance of cheese to the Italian economy and culinary culture, tradition is one of the main attributes for promoting cheese products. Tradition in typical foods is a multidimensional concept encompassing temporal, geographical, know-how, and cultural dimensions [26,27]. These dimensions appear through production dates, authentic processing methods, and storytelling elements on packaging. Tradition significantly influences the perception and acceptance of cheese, as consumers often prefer products made using traditional methods and local raw materials [1,28]. These products are often considered of higher quality and better taste than their industrial counterparts [29,30]. In recent decades, there has been a growing demand for food produced by traditional methods with a strong link to a particular area [31].

Sensory attributes also play a crucial role in consumer decision-making by influencing product perception and evaluation [32]. Descriptions of sensory aspects (e.g., taste, aroma, texture, color, consistency, etc.) can provide consumers with useful information about the quality and characteristics of cheese, helping them make more informed choices that suit their personal tastes [33].

The naturalness of food products has been one of the elements considered by consumers since the early 2000s, when the clean label movement gained momentum. Although consumers are increasingly concerned about natural products, the term “natural” has no clear definition, neither in terms of regulation (by the Food and Drug Administration or EU regulations) nor in consumers’ perceptions [34,35,36]. Therefore, consumers mainly use labels indicating “free-from” claims and “natural” claims as guides to avoid ingredients perceived as unnatural (e.g., preservatives, additives, colorants, GMOs, etc.) [37].

Sustainability attributes have gained importance as consumers have become more concerned about production methods. Studies consistently show consumers have positive willingness to pay for sustainable agri-food attributes such as organic production and animal welfare [38,39,40,41,42].

Other quality indications related to product specifications are also important [1,2,43]. For instance, cheese ripening periods, the origin of raw materials, and location (mountain product) are crucial. In particular, the “mountain product” quality label introduced through EU Regulation No. 1151/2012 [44] and EU Regulation No. 665/2014 [45] has been found to positively influence cheese purchasing decisions among consumers sensitive to the impact of their food choices on the environment, the local area, and animal welfare [46].

Previous research has demonstrated that individual attribute dimensions exert a variable yet meaningful influence on consumer preferences for cheese products. However, the specific economic valuation of different attribute combinations—particularly within the context of Italian PDO cheeses—remains underexplored. Moreover, there has been relatively limited application of hedonic pricing models in this segment, despite their usefulness in quantifying the monetary value that consumers assign to specific product characteristics. Existing studies employing hedonic models have primarily focused on the influence of distribution channels and the complexity of labeling strategies. For example, Schröck (2014) found that the price premium for labeled cheeses such as organic and PDO products varies by retail format, with higher prices observed in hypermarkets and specialty shops than in discount outlets [47]. Teuber (2011) further highlighted the potential negative impact of “label overload,” noting that too many overlapping certifications may confuse consumers and dilute the perceived value of each label [48]. Despite these valuable contributions, the hedonic pricing literature on cheese has largely neglected key symbolic dimensions such as tradition, perceived quality, and sustainability. These attributes are increasingly emphasized in both policy frameworks and consumer communication, especially for PDO products, which are often marketed as embodying heritage and environmentally responsible production. Their absence from hedonic models represents a significant gap, limiting our understanding of the drivers of price formation in quality-differentiated cheese markets. Integrating these dimensions into future hedonic analyses would provide a more comprehensive and policy-relevant understanding of consumer valuation in the dairy sector.

In essence, the literature confirms the importance of several attributes, such as naturalness, typicality, and traditionality, as well as the effectiveness of communicating these attributes on labels to enhance consumer appreciation and willingness to pay. However, the effects of these attributes clearly vary according to product type, distribution channel, market context, and the simultaneous presence of multiple attributes on the label. Therefore, it is essential to deepen our understanding of how different label attributes impact price premiums in real market conditions. Hedonic price analysis provides an effective methodological tool to fill this knowledge gap by quantifying the market value of different attributes across cheese categories.

2. Materials and Methods

We first identified the primary dimensions of cheese attributes from previous research on consumers’ perceptions of cheese products [2,6,41,49]. The identified dimensions were quality, tradition, sensory, naturalness, nutrition, and sustainability. Subsequently, qualitative research was conducted to discuss and verify these dimensions and to create subdimensions for our target products. We conducted three focus groups (n = 30) and four in-depth interviews with representatives from each PDO cheese consortium.

Results from the qualitative research were used as input for the quantitative research. For the quantitative phase, market surveys were conducted to collect label samples from target products. Content analysis was then performed on the label samples to determine the final main dimensions and subdimensions. Finally, a hedonic pricing method was employed to analyze the effect of different attributes on prices. We describe our quantitative research steps in detail in the following subsections. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Parma (Review number: 0238340) prior to data collection.

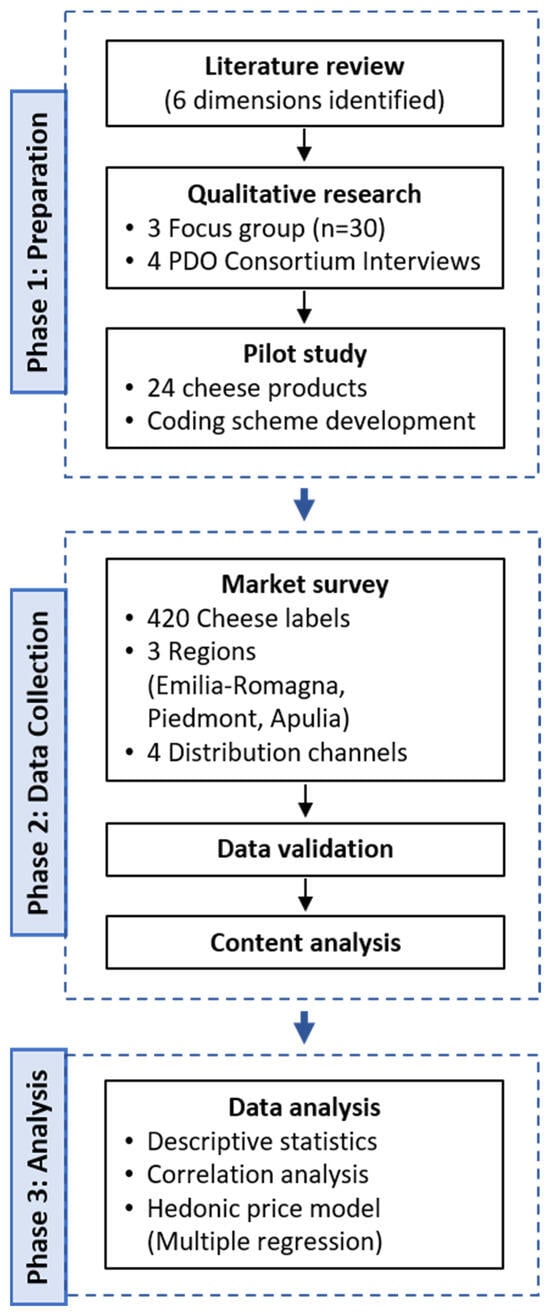

Figure 1 provides an overview of the complete research process, illustrating the sequential progression from initial conceptualization through data collection to final analysis. The three sequential phases comprise (1) preparation, including literature review, qualitative research, and pilot study; (2) data collection, encompassing market survey, validation, and content analysis; and (3) analysis, including statistical methods used to evaluate the data.

Figure 1.

Research process flowchart.

2.1. Development of a Coding Scheme and a Survey Tool

Given the variability of information displayed on cheese packaging in the market, a pilot survey was conducted to identify information associated with each dimension. This survey took place in Parma in September 2022, involving visits to two supermarkets and one discount store. The packaging of 24 cheese products—representing a variety of target products—was photographed by one researcher, while other researchers used content analysis (Content analysis is a method used to analyze and describe the content of any form of communication in a systematic, objective, and quantitative way) [27,50,51] to analyze the data extracted from the images and generate a list of cheese label dimensions and subdimensions. Subsequently, all researchers discussed and developed a coding scheme comprising a comprehensive list of pertinent elements displayed on cheese labels. The coding scheme included detailed instructions and examples to minimize subjectivity, uncertainty, and ambiguity while ensuring clear understanding of each category.

An online survey tool (the questionnaire is available upon request) [52] was developed based on the coding scheme to facilitate data collection. The questionnaire structure included nine sections: Part 1—General information (e.g., distribution channels, brand types, raw material types); Part 2—Nutritional dimension; Part 3—Naturalness dimension; Part 4—Quality dimension; Part 5—Tradition dimension; Part 6—Sensory dimension; Part 7—Sustainability dimension; Part 8—Packaging; and Part 9—Price and promotion.

2.2. Data Collection

Data collection was carried out using a convenience sample from October to December 2022 at different distribution channels (supermarkets, discount stores, open-air markets, and cheese specialty stores) in three regions (Emilia-Romagna, Piedmont, and Apulia). Target products were hard cheese (Parmigiano Reggiano PDO and Grana Padano PDO), fresh soft cheese (Roccaverano PDO and robiola type), and string cheese (Caciocavallo Silano PDO and caciocavallo type). For hard cheese, we compared only the two PDO cheeses because these are the primary competitors in the market. All surveyed products were sold in pieces; while shredded, cubed, and grated products were excluded. Trained researchers and personnel from a private agency carried out the data collection. Due to the study’s broad scope covering three cheese categories across multiple regions and distribution channels, we employed convenience sampling. This approach was necessary given the logistical complexity and resource constraints of surveying all possible retail locations. We focused on major distribution channels where cheese is commonly sold to ensure reasonable market representation.

First, data collectors visited distribution channels and took pictures of target products (if feasible, using two products in the same picture; see Figure 2). Product pricing per kg and promotional information were also documented. Only information from product packaging, price, and promotions at the store was recorded, as this is the information consumers typically see when purchasing products. Collectors then uploaded pictures and completed the online survey on the same day. Subsequently, researchers validated and corrected the data by comparing it with the uploaded images. The final validated dataset consisted of 420 cheese product labels. Following data collection, a final coding scheme (Table 1) was developed and shared with stakeholders for final modifications.

Figure 2.

Representative examples of cheese packaging from the market survey.

Table 1.

The coding scheme for cheese labels.

For correlation analysis, the frequency was then converted into a score. This scoring approach follows the methodology established by Charmpi et al. [27] for systematically quantifying food label attributes. For each coding category, the allocation of points was based on elements displayed on a label. Within each dimension, the combined scores across all coding categories sum to 100 points, with each coding category contributing equally (e.g., 20 points per category for the five categories in the Quality dimension). The data collected from the survey tool were then coded according to the final coding scheme. The researchers who performed the coding were instructed to consider only the information displayed on the product label. Further details and coding examples are provided in Supplementary Material S1 and Figure S1.

2.3. Data Analysis

The data analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 28.0 [53]. Descriptive statistics were reported for each product category. Pearson correlations between dimensions and prices were calculated. One-way ANOVA analyses and post hoc Tukey’s HSD tests were performed to determine whether there were significant differences in product prices among different brand types.

We used the hedonic pricing method [54] to determine the price premiums associated with distinctive attributes (coding categories). This approach is based on utility maximization theory, where price is determined by both the utility gained by the consumer from a product’s characteristics (attributes) and the price set by the producer [55,56].

The price of each product is determined by a set of its characteristics or attributes. Assuming that cheese has k characteristics (e.g., PDO label, cheese ripening, organic logo, etc.), the cheese price is defined as follows:

Price (z) = f(z1, z2, …, zk)

Multiple regression analyses were performed for each cheese category, using the backward method, to investigate how sales prices were affected by different characteristics. This then enabled the identification of significant variables for each type of cheese. The log-linear functional form was used, as it is commonly used for variables that contain monetary values (e.g., salaries, prices, and expenditures) [57]. Each model followed the same basic equation measuring the relationship between price and the independent variables under consideration. The general form of this equation is

where p is the actual sales price of cheese per kilogram in euros, zi is a vector representing cheese attribute i, βi is a coefficient for product attribute i, and ε is an error term. Cheese attribute variables are vectors of dummy variables that have a value of 1 if present and 0 otherwise. An exception is the cheese ripening variable, which is a continuous variable indicating the number of months the cheese has been ripening. Finally, brand types and distribution channels were included in the models due to their importance to cheese prices.

ln(p) = β0 + Σ βizi + ε

3. Results

3.1. Distribution Channels, Brand Types, and Prices of the Products

In total, 87 products (21%) were Parmigiano Reggiano PDO, 153 products (36%) were Grana Padano PDO, 18 products (4%) were Roccaverano PDO, 94 products (22%) were robiola type, 31 products (7%) were Caciocavallo Silano PDO, and 37 products (9%) were caciocavallo type. Overall, 289 products (69%) were Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) products.

The majority of products (77%) were sourced from supermarkets, followed by discount stores (13%), open air markets (5%), and cheese specialty stores (5%). Of the total, 231 products (55%) were manufacturer brands, while 143 products (34%) were private brands (divided into 46 house brands and 97 premium house brands), and 46 products (11%) were unbranded. The latter are typically sold ready-cut in plastic wrap, with Parmigiano Reggiano PDO and Grana Padano PDO identified by the names engraved on their rinds.

Regarding product prices (Table 2), it should be noted that Roccaverano PDO products are only marketed under the producer’s brand name, while other cheeses are marketed under both producer’s brand names and private labels. Price variations for Parmigiano Reggiano PDO and Grana Padano PDO derived from different cheese ripening periods, while the significant price differences among robiola types are due to the wide range of products and brands. In addition, because robiola types without brand information were mostly collected from open-air markets and cheese specialty stores, their prices are higher than those in supermarkets.

Table 2.

Brand types and product prices in the market.

For Grana Padano PDO, results of ANOVA tests showed that prices were significantly different among brand types (F(2, 150) = 3.458, p = 0.034). The post hoc Tukey’s HSD test revealed that the mean price of products without brand information was significantly lower than that of private brands (p = 0.030, 95% CI = [−4.026, −0.166]).

Prices of Caciocavallo Silano PDO were significantly different among brand types (F(2, 28) = 3.997, p = 0.030), with manufacturer brands being significantly higher than private brands (p = 0.028, 95% CI = [0.302, 6.120]). Prices of robiola types were also significantly different among brand types (F(2, 91) = 9.086, p < 0.001), with private brands being significantly lower than unbranded products (p = 0.004, 95% CI = [2.295, 13.837]) and manufacturer brands (p = 0.001, 95% CI = [1.849, 7.726]).

3.2. Presence of Different Dimensions on the Products and Their Correlation with Prices

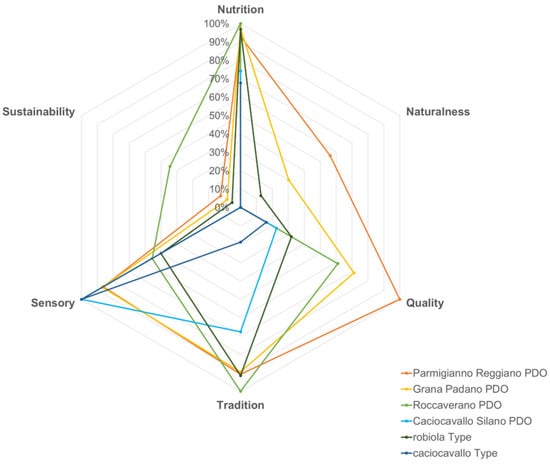

Figure 3 illustrates the relative prominence of the six dimensions (quality, tradition, sensory, naturalness, nutrition, and sustainability) across different cheese categories using comparative radar charts. These dimensions are based on the relative frequency of each dimension per category, ranging from 0% to 100%. Further details on absolute and relative frequencies of dimensions and subdimensions were provided in Supplementary Material S2 and Table S1.

Figure 3.

Dimension profiles across all cheese categories.

In general, quality and tradition were the most important dimensions for cheese products in the Italian market, as most products displayed these dimensions. The sensory dimension was also prominent, but mostly because products were packed in transparent packaging. The nutrition dimension is important for all products since it is required by law. Some products also included references to naturalness. Across all categories, the sustainability dimension consistently showed the lowest representation, suggesting a potential area for market differentiation.

The labels of Parmigiano Reggiano PDO and Grana Padano PDO products were more complex, as they contained most dimensions; quality and tradition dimensions were crucial, followed by sensory, naturalness, and sustainability dimensions, respectively, though the sustainability dimension was mentioned infrequently. Parmigiano Reggiano PDO mentioned quality and naturalness dimensions more often than Grana Padano PDO.

Quality and tradition dimensions were prominent in Roccaverano PDO, while this cheese promoted the sustainability dimension (animal welfare) more than other product types. Robiola-type products also emphasized the tradition dimension through references to know-how and artisan elements, while also highlighting the naturalness of their products.

The tradition dimension was important for Caciocavallo Silano PDO, even though to a lesser extent than for other PDO cheeses. In contrast, caciocavallo type rarely mentioned any dimension besides mandatory nutrition labels.

Regarding the correlations among dimensions, prices, and product types (further details in Supplementary Material S3 and Table S2), for Parmigiano Reggiano PDO, there was a strong correlation between price and all dimensions. Most dimensions were correlated with one another, except quality, which was uncorrelated with naturalness and nutrition, while sensory was uncorrelated with sustainability. For Grana Padano PDO, all dimensions except sensory and naturalness had strong correlations with price. Sensory features did not correlate with any other dimension. For robiola type, the sustainability dimension was strongly correlated with price, while the naturalness dimension was negatively correlated with it. For caciocavallo type, only the quality dimension had a strong correlation with price. There were no correlations between price and any dimensions for Roccaverano PDO and Caciocavallo Silano PDO products. This might be because many of them were sold at cheese specialty stores without labeling or packaging but at higher prices.

3.3. Results of the Estimated Models

Table 3 presents the results of the multiple regression models for hard cheese (Parmigiano Reggiano PDO and Grana Padano PDO), fresh soft cheese (Roccaverano PDO and robiola type), and string cheese (Caciocavallo Silano PDO and caciocavallo type).

Table 3.

Estimates of the hedonic price models for hard cheese, fresh soft cheese, and string cheese categories.

For the hard cheese category, the overall regression was statistically significant (R2 = 0.812, F(14, 225) = 69.31, p < 0.001). Parmigiano Reggiano PDO commands a 17.8% price premium over Grana Padano PDO. Sustainability attributes show the following particularly strong effects: animal welfare claims generate a 30.7% premium, organic certification yields a 29.4% premium, and sustainable packaging yields an 11.9% premium. Among quality attributes, cow breed specification generates the largest premium at 29.4%, while each additional month of ripening increases the price by 0.8%. Naturalness claims (such as natural or no GMOs) add a 10.3% premium. Distribution channels significantly impact pricing, with discount stores and open-air markets showing 20.8% and 28.5% lower prices, respectively, compared to supermarkets. Products with transparent packaging (showing color) have 9.0% lower prices. Keywords related to authenticity (such as gastronomic culture, tradition) and private brands generate price premiums. These findings indicate substantial returns on investment for producers who emphasize quality, sustainability, and naturalness attributes on their hard cheese labels.

For the fresh soft cheese category, the overall regression was statistically significant (R2 = 0.388, F(6, 105) = 11.1, p < 0.001). Roccaverano PDO commands a substantial 23.1% price premium over non-PDO robiola types. The organic certification generates the largest attribute premium at 32.8%. Notes for degustation add a 15.3% premium, though this is marginally significant (p = 0.086). Distribution channels strongly impact prices; products at specialty stores command 19.8% higher prices than those at supermarkets, while discount store prices are 23.6% lower. Private brands face a substantial price disadvantage of 17.9% compared to unbranded products. Note that unbranded products in this study were more expensive because they were typically sold at cheese specialty stores. These findings highlight the economic importance of PDO certification, organic labeling, and strategic channel selection for fresh soft cheese producers.

For the string cheese category, the overall regression was statistically significant (R2 = 0.347, F(3, 64) = 11.34, p < 0.001). Unlike other cheese categories, the prices of Caciocavallo Silano PDO were not significantly different from those of the caciocavallo type. Instead, cow breed specification emerged as the dominant value driver, creating a substantial 61.1% price premium. Distribution channels maintained their economic significance, with specialty stores commanding 24.2% higher prices than supermarkets. These findings suggest string cheese producers should incorporate quality (particularly cow breed specification) on labels to increase economic returns.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the elements found on PDO and non-PDO cheese labels for hard cheese, fresh soft cheese, and string cheese products, as well as to examine the relationships between prices and product attributes using the hedonic pricing method. The results indicated that traditional and quality dimensions were prominently displayed on cheese labels, suggesting their importance in marketing cheese products in the Italian market. This outcome appears to be consistent with previous studies [1,2,6,58]. Other factors such as sustainability, sensory and natural qualities, brand, and distribution channel also influenced cheese prices; however, their impact depended largely on the type of cheese. For instance, hard cheese products displaying quality information (such as cow breed specification and cheese ripening) had higher prices than products without this information [6,59].

Roccaverano PDO generated a substantial 23.1% price premium over non-PDO robiola types, confirming the economic value of PDO certification for fresh soft cheeses. However, string cheese prices were determined by additional information (e.g., cow breed specification) and distribution channels rather than the PDO label. This result suggests that for some products, other elements are needed to complement PDO certification. Furthermore, unlike other products, string cheese packaging rarely included any information. The lack of information on the label may be due to the widespread practice of selling this cheese unpackaged, in both open-air markets and cheese specialty stores. In these cases, the seller, often the producer, directly communicates product information and characteristics, building a trusting relationship with the buyer.

The sustainability dimension contributed to premium prices for hard cheese products, with animal welfare claims generating a 30.7% premium, organic certification yielding a 29.4% premium, and sustainable packaging adding an 11.9% premium. For fresh soft cheese, organic certification created a 32% premium. This result is consistent with previous studies [9,38,49,60,61] showing that attributes linked to sustainable production processes have significant effects on consumer food choices and command premium prices. Nevertheless, sustainability attributes were less apparent in the surveyed products (10% of hard cheese and nearly 50% of Roccaverano PDO products). The possible reason could be that producers focused more on other dimensions, such as tradition and quality. Despite the small numbers, packaging is progressively becoming more biodegradable and recyclable [62,63,64,65,66]. Hence, our findings confirm that sustainability attributes can be used as a differentiation strategy by suppliers.

The sensory dimension, especially instructions for degustation, was associated with higher prices for hard cheese and fresh soft cheese products. However, hard cheese products with transparent packaging had lower prices. This may have been because it was difficult to distinguish these packages from others as they contained little to no information. In addition, consumers’ changing lifestyles increase demand for packaged products with clear information, particularly for PDO products, which must be produced following specific specifications [2,62,67].

The naturalness dimension was important mainly for Parmigiano Reggiano PDO and Grana Padano PDO. Claims of “natural product” and “no GMOs” created positive price premiums. Because these cheeses are naturally lactose-free due to the cheese ripening process, this indication was used to inform consumers concerned about this issue, though it had no substantial influence on prices. The claim “Additives-free” also appeared on some products, especially Parmigiano Reggiano PDO, as its production specifications prohibit the use of any additives. This finding confirmed the importance of naturalness in cheese products [68,69,70] in the Italian market, though some claims did not generate premium prices.

The nutrition dimension was important for all products because of EU regulation No. 1169/2011 [71] on the provision of food information to consumers, which requires producers to provide nutrition information since 13 December 2016. However, it did not allow product differentiation, except for nutritional labeling for Parmigiano Reggiano PDO. Nevertheless, the European Union’s intention to implement a harmonized mandatory front-of-pack nutrition labeling on packaged food [72] could increase the potential for product differentiation based on nutritional labels. Future research could estimate the effect of different nutrition labels on PDO cheese products.

Brand types significantly affected product prices, though the results were heterogeneous. Private brands had a price premium for the hard cheese category, while these brands had lower prices than manufacturer brands and unbranded products for the fresh soft cheese category. In the case of unbranded products, the effect was likely from the distribution channel because they were usually sold at cheese specialty stores. Future research could test the interaction effect of distribution channels and brand types.

Distribution channels had a significant impact on product prices as well. For example, products at cheese specialty stores had higher prices than those at other distribution channels because customers expected to find high-quality products there. This aligns with [73], who found that consumers seeking specific quality attributes often shop at specialty stores despite higher prices. This supports our finding that specialty cheese stores charged higher prices; they attracted customers specifically looking for authentic PDO cheeses who accepted premium pricing for these special products. The channel was especially important for the fresh soft cheese and string cheese categories. However, this was not the case for Parmigiano Reggiano PDO and Grana Padano PDO, which were more dependent on cheese ripening period (the longer the ripening period, the higher the price) and other attributes (such as sustainability, quality, tradition, and sensory).

Modern retail channels, especially large supermarket chains, have an advantage in terms of negotiating power with manufacturers and suppliers with whom retailers negotiate directly. Increased channel concentration may generate lower unit costs for manufacturers (e.g., for distribution and warehousing) related to serving one large retailer instead of several small retailers, but it also increases bargaining power for large retailers. The purchasing power of large retailers is realized through price discounts, special offers, and payment deferrals from manufacturers, which become more signification the greater the competition between manufacturers. Price reductions are proportionate to the level of competition in the distribution sector and are only partially passed on to final consumer [74]. The market power of distributors is further increased by the practice of selling products under their own brand, the so-called “private labels”, which often allow cheaper cheeses with the retailer’s brand to occupy the best positions on shelves [75]. The Italian association of dairy processors reported that in 2017, private brands accounted for 19.1% of total sales of dairy products in modern distribution [76]. Nevertheless, the competitive positioning of private brands varied greatly among cheese categories. Grana-type cheeses with private labels made up around 37% of the total sales value in this cheese category. On the other hand, sales of fresh industrial cheeses and string cheese with private brands were low, at 3.7% and 11.5%, respectively [76].

Our findings reveal distinct patterns of value creation across cheese categories, with important implications for producers and policymakers. For hard cheeses (Parmigiano Reggiano PDO and Grana Padano PDO), sustainability attributes emerged as the most powerful differentiators, suggesting that investments in organic certification and animal welfare practices would yield the highest returns. Fresh soft cheeses showed a different pattern, where PDO certification (particularly for Roccaverano PDO) and strategic distribution through specialty stores created the most significant premiums. String cheese markets responded primarily to specific quality indicators, especially cow breed specification, with distribution channels also playing a crucial role. These category-specific insights suggest that rather than applying uniform strategies across all PDO cheeses, producers and consortia should tailor their approaches to the unique value drivers within each cheese category.

While our analysis focuses on price premiums, it is important to note that PDO certification involves higher production costs than non-certified products. Producers must ensure high-quality raw materials and follow strict production specifications. The certification system requires various fees: an initial registration fee, annual fixed fees (which may vary by production volume), variable fees based on the number of certified cheese wheels, and costs for required laboratory tests [77]. Research shows that PDO products can achieve price premiums that cover these higher costs, especially in domestic markets [78,79]. However, company size and production volume strongly affect profitability [6,80]. Small producers often cannot afford certification due to a lack of economies of scale, so they may sell locally without PDO labels, relying instead on their reputation [81]. Future research should separate production costs from market prices to better understand when PDO certification is economically worthwhile for different types of producers. Additionally, emerging digital technologies may offer new ways to enhance PDO value. The authors of [82] found that the Parmigiano Reggiano Consortium successfully uses integrated digital tools for quality monitoring and traceability, strengthening producer networks while preserving traditional methods. Future research could explore how digital innovation complements traditional PDO certification schemes and potentially reduces costs while maintaining authenticity.

While this study provides valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. First, we used convenience sampling. While convenience sampling is not probabilistic and therefore limits the generalizability of results to the broader population, it can still yield valid and informative findings when the sample is reasonably diverse and aligns with the study objectives [83]. In this context, the use of a convenience sample is justified by the study’s objective to explore patterns of cheese labels. Furthermore, convenience sampling may be appropriate when the target population is difficult to define precisely, or when the product in question is niche or specialty-oriented [84,85,86], as is often the case in research involving PDO or sustainable food products.

A second limitation is that the main survey points were supermarkets rather than other distribution channels. However, this approach is justified given that Italian consumers predominantly purchase food at supermarkets, which remain the primary channel for food purchases in Italy, accounting for 40% of the market share [74].

Third, the content analysis method has a limitation in that it can be reductive, meaning that emphasizing words or phrases alone can minimize the importance of complex concepts. We attempted to address this issue by documenting every element included on the labels. Fourth, the study only analyzed labels and prices of the products; it did not test actual consumer perceptions or willingness to pay directly. Future research could focus on consumers’ perceptions toward different dimensions in comparison to the findings of this study and on market share studies.

Finally, there is a disparity in the sample sizes across different cheese varieties examined. While most cheeses were well-represented, Roccaverano PDO had a smaller sample due to its limited availability in the marketplace. This unequal distribution represents a methodological limitation that could potentially affect the robustness of comparisons between cheese categories. Despite this constraint, the methodology and findings serve as a valuable framework for future research on these specialty cheeses, particularly for less common PDO varieties like Roccaverano.

5. Conclusions

The findings hold implications for policymakers and certification bodies aiming to enhance the economic value of quality and sustainability labels within competitive markets.

Managers and practitioners could use our findings to benchmark their products and assess how they are positioned in relation to those of their competitors. Emphasizing tradition, quality specifications, and sensory attributes creates added value. Sustainability attributes, while less common on cheese products, generate significant price premiums, representing an underutilized differentiation opportunity. PDO certification adds value to cheese products; however, other dimensions are also important, highlighting the complexity of consumer requirements regarding multiple issues beyond just PDO certification.

Our contribution also includes empirical evidence that optimal distribution channels vary depending on product characteristics. Products at cheese specialty stores have significantly higher prices than those at supermarkets, with premiums of 19.8% for fresh soft cheese and 24.2% for string cheese. On the other hand, hard cheeses show less channel dependency, allowing for broader distribution approaches.

Regarding brand and price relationships, the patterns differ among cheese categories. For hard cheeses, both manufacturer and private brands create similar premiums compared to unbranded products. In contrast, for soft cheeses, manufacturer brands command significantly higher premiums than private labels, highlighting a stronger brand-driven differentiation in this segment and suggesting greater market opportunities for branded soft cheese producers.

Beyond these findings, the novelty of this study lies in its integrated methodological approach, which combines content analysis with a hedonic pricing model and multiple linear regression analysis to evaluate how specific product attributes, branding strategies, and distribution channels influence retail pricing. This approach is particularly innovative within the context of the cheese market, where previous research has rarely provided such a granular and quantitative analysis of price determinants across multiple cheese types.

Most hedonic price studies in the agri-food sector have focused either on single product categories or general attributes, often overlooking the interplay between brand types, certification schemes (such as PDO), and retail environments. By analyzing these dimensions simultaneously and linking them to market prices, this study offers a systematic and transferable framework for producers and retailers. It enables them not only to benchmark their products against competitors but also to optimize pricing strategies based on which attributes are most valued by consumers.

Moreover, policymakers could help producers by creating standard guidelines for communicating sustainability attributes that consumers value. Digital tools like QR codes on packaging could provide detailed information about production methods, sustainability practices, and product stories that do not fit on physical labels. These digital solutions would especially benefit small PDO producers who cannot afford expensive label changes but want to communicate their unique value propositions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17135891/s1, Figure S1: Examples of coding of (a) Parmigiano Reggiano PDO and (b) Grana Padano PDO labels; Table S1: The frequency and relative frequency (%) of occurrence of different dimensions reflected on the labeling of the products; Table S2: Means, standard deviation and correlation among the dimensions and cheese prices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M., A.D.B., G.D.V., C.B. and R.W.; methodology, C.M., R.W., A.D.B., G.D.V. and C.B.; software, R.W.; validation, R.W. and C.M.; formal analysis, R.W.; investigation, E.M., A.D.B., G.D.V. and C.B.; data curation, R.W.; writing—original draft preparation, R.W. and E.M.; writing—review and editing, All authors.; supervision, C.M., A.D.B. and G.D.V.; funding acquisition, C.M., A.D.B. and G.D.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was a part of the project “PDOnonPDO: Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) or non-PDO cheeses: the interplay of consumer preferences and cheeseomics”, funded by PRIN: Progetto di ricerca di rilevante interesse nazionale—Bando 2020—Prot.2020NRKHAJ.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Parma (Review number: 0238340).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Braghieri, A.; Girolami, A.; Riviezzi, A.M.; Piazzolla, N.; Napolitano, F. Liking of Traditional Cheese and Consumer Willingness to Pay. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 13, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, C.; Aquilani, B.; Piccarozzi, M.; Ruggieri, A. Consumer Quality Perception in Traditional Food: Parmigiano Reggiano Cheese. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2019, 32, 141–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLAL UE-27: Settore Lattiero Caseario. Available online: https://www.clal.it/index.php?section=stat_ue15 (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- CLAL Consumi Pro-Capite. Available online: https://www.clal.it/?section=tabs_consumi_procapite (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- ISMEA Tendenze e Dinamiche Recenti: Lattiero Caseari—Dicembre 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.ismeamercati.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/13337 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Menozzi, D.; Yeh, C.-H.; Cozzi, E.; Arfini, F. Consumer Preferences for Cheese Products with Quality Labels: The Case of Parmigiano Reggiano and Comté. Animals 2022, 12, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISMEA Qualivita RAPPORTO ISMEA—QUALIVITA 2024 Sulle Produzioni Agroalimentari e Vitivinicole Italiane DOP, IGP e STG; 2024. Available online: https://www.qualivita.it/rapporto-ismea-qualivita-2024/ (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- GS1 Italy Osservatorio Immagino di GS1 Italy. Le Etichette dei Prodotti Raccontano i Consumi Degli Italiani. Available online: https://servizi.gs1it.org/osservatori/osservatorio-immagino-15/#item64821 (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Almli, V.L.; Naes, T.; Enderli, G.; Sulmont-Rossé, C.; Issanchou, S.; Hersleth, M. Consumers’ acceptance of innovations in traditional cheese. A comparative study in France and Norway. Appetite 2011, 57, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.P.L.; Carneiro, J.d.D.S.; De Melo Ramos, T.; Patterson, L.; Pinto, S.M. Determining how packaging and labeling of Requeijão cheese affects the purchase behavior of consumers of different age groups. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacef, M.; Lelièvre-Desmas, M.; Symoneaux, R.; Jombart, L.; Flahaut, C.; Chollet, S. Consumers’ expectation and liking for cheese: Can familiarity effects resulting from regional differences be highlighted within a country? Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 72, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetti, E.; Mattiacci, A.; Simoni, M. Communication patterns to address the consumption of PDO products. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 390–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, A.; Hayes, H.E.; Ni, H.; Raikos, V. A comparison of the nutritional content and price between dairy and non-dairy milks and cheeses in UK supermarkets: A cross sectional analysis. Nutr. Health 2022, 30, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. How does origin labelling on food packaging influence consumer product evaluation and choices? A systematic literature review. Food Policy 2023, 119, 102503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, B.; Costa Leite, J.; Rayner, M.; Stoffel, S.; van Rijn, E.; Wollgast, J. Consumer Interaction with Sustainability Labelling on Food Products: A Narrative Literature Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Baldin, A. The country of origin effect: A hedonic price analysis of the Chinese wine market. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1264–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballco, P.; Jaafer, F.; de Magistris, T. Investigating the price effects of honey quality attributes in a European country: Evidence from a hedonic price approach. Agribusiness 2022, 38, 885–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, S.; Joly, M.; Poelmans, E. Search characteristics, online consumer ratings, and beer prices. Agribusiness 2024, 40, 804–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irek, J. Price Premiums for Single-Name and Compound-Name Geographical Indications in Swiss Cheese Trade. Agribusiness 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heide, M.; Olsen, S.O. The use of food quality and prestige-based benefits for consumer segmentation. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2349–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, E.; Murad, M.D.W.; Freeman, S. Factors influencing price premiums of Australian wine in the UK market. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2018, 30, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mameno, K.; Kubo, T.; Shoji, Y. Price premiums for wildlife-friendly rice: Insights from Japanese retail data. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021, 3, e417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verza, M.; Ceccacci, A.; Frigo, G.; Mulazzani, L.; Chatzinikolaou, P. Legumes on the Rise: The Impact of Sustainability Attributes on Market Prices. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimbo, F.; Nico, K.; De Meo, E. Assessing the Quality and Floral Variety Market Value: A Hedonic Price Model for Honey. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, F.; Tawfik, R.; Ameen, F.A. Determinants of Bottled Water Prices in Saudi Arabia: An Application of the Hedonic Price Model. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amilien, V.; Hegnes, A.W. The dimensions of ‘traditional food’ in reflexive modernity: Norway as a case study. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 3455–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmpi, C.; Vervaet, T.; Van Reckem, E.; Geeraerts, W.; Van der Veken, D.; Ryckbosch, W.; Leroy, F.; Brengman, M. Assessing levels of traditionality and naturalness depicted on labels of fermented meat products in the retail: Exploring relations with price, quality and branding strategy. Meat Sci. 2021, 181, 108607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo-Milpa, M.; Arriaga-Jordán, C.M.; Cesín-Vargas, A.; Espinoza-Ortega, A. Characterisation of consumers of traditional foods: The case of Mexican fresh cheeses. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 915–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, L.; Guàrdia, M.D.; Xicola, J.; Verbeke, W.; Vanhonacker, F.; Zakowska-Biemans, S.; Sajdakowska, M.; Sulmont-Rossé, C.; Issanchou, S.; Contel, M.; et al. Consumer-driven definition of traditional food products and innovation in traditional foods. A qualitative cross-cultural study. Appetite 2009, 52, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhonacker, F.; Lengard, V.; Hersleth, M.; Verbeke, W. Profiling European traditional food consumers. Br. Food J. 2010, 112, 871–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vita, G.; Maesano, G.; Zanchini, R.; Barbieri, C.; Spina, D.; Caracciolo, F.; D’Amico, M. The thin line between tradition and well-being: Consumer responds to health and typicality attributes for dry-cured ham. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 364, 132680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puleo, S.; Braghieri, A.; Condelli, N.; Piasentier, E.; Di Monaco, R.; Favotto, S.; Masi, P.; Napolitano, F. Pungency perception and liking for pasta filata cheeses in consumers from different Italian regions. Food Res. Int. 2020, 138, 109813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahne, J. Sensory science, the food industry, and the objectification of taste. Anthropol. Food 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, V.E.; Tran, T.; Chambers, I.V.E. Natural: A $75 billion word with no definition—Why not? J. Sens. Stud. 2019, 34, e12501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murley, T.; Chambers, E. The Influence of Colorants, Flavorants and Product Identity on Perceptions of Naturalness. Foods 2019, 8, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racette, C.M.; Homwongpanich, K.; Drake, M.A. Consumer perception of Cheddar cheese color. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 5512–5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asioli, D.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Caputo, V.; Vecchio, R.; Annunziata, A.; Næs, T.; Varela, P. Making sense of the “clean label” trends: A review of consumer food choice behavior and discussion of industry implications. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De-Magistris, T.; Gracia, A. Consumers’ willingness to pay for light, organic and PDO cheese: An experimental auction approach. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Hu, W.; Huang, W. Are Consumers Willing to Pay More for Sustainable Products? A Study of Eco-Labeled Tuna Steak. Sustainability 2016, 8, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, L.; Torquati, B.; Chiorri, M. Sustainable agri-food products: A review of consumer preference studies through experimental economics. Agric. Econ. Ekon. 2018, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kallas, Z. Meta-analysis of consumers’ willingness to pay for sustainable food products. Appetite 2021, 163, 105239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Seo, H.-S.; Fang, D.; Hogan, V.J.; Nayga, R.M., Jr. Sustainability information, taste perception and willingness to pay: The case of bird-friendly coffee. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 115, 105124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzi, E.; Donati, M.; Mancini, M.C.; Guareschi, M.; Veneziani, M. PDO Parmigiano Reggiano Cheese in Italy BT—Sustainability of European Food Quality Schemes: Multi-Performance, Structure, and Governance of PDO, PGI, and Organic Agri-Food Systems; Arfini, F., Bellassen, V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 427–449. ISBN 978-3-030-27508-2. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 November 2012 on Quality Schemes for Agricultural Products and Foodstuffs. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32012R1151 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- European Commission Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No 665/2014 of 11 March 2014 Supplementing Regulation (EU) No 1151/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council with Regard to Conditions of Use of the Optional Quality Term ‘Mountain Product’. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32014R0665 (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- Marescotti, M.E.; Amato, M.; Demartini, E.; La Barbera, F.; Verneau, F.; Gaviglio, A. The Effect of Verbal and Iconic Messages in the Promotion of High-Quality Mountain Cheese: A Non-Hypothetical BDM Approach. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröck, R. Valuing country of origin and organic claim. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1070–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teuber, R. Consumers’ and producers’ expectations towards geographical indications. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 900–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchi, C.; Orsi, L.; Sali, G. Consumers’ Attitudes for Sustainable Mountain Cheese. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berelson, B. Content Analysis in Communication Research; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Kassarjian, H.H. Content Analysis in Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 1977, 4, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualtrics Qualtrics 2022. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Waugh, F. V Quality Factors Influencing Vegetable Prices. J. Farm Econ. 1928, 10, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, K.J. A new approach to consumer theory. J. Polit. Econ. 1966, 74, 132–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, S. Hedonic Prices and Implicit Markets: Product Differentiation in Pure Competition. J. Polit. Econ. 1974, 82, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.C.; Griffiths, W.E.; Lim, G.C. Principles of Econometrics, 5th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Savelli, E.; Bravi, L.; Francioni, B.; Murmura, F.; Pencarelli, T. PDO labels and food preferences: Results from a sensory analysis. Br. Food J. 2020, 123, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tura, M.; Gagliano, M.A.; Soglia, F.; Bendini, A.; Patrignani, F.; Petracci, M.; Gallina Toschi, T.; Valli, E. Consumer Perception and Liking of Parmigiano Reggiano Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) Cheese Produced with Milk from Cows Fed Fresh Forage vs. Dry Hay. Foods 2024, 13, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonadonna, A.; Peira, G.; Giachino, C.; Molinaro, L. Traditional Cheese Production and an EU Labeling Scheme: The Alpine Cheese Producers’ Opinion. Agriculture 2017, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, I.; Carzedda, M.; Grassetti, L.; Iseppi, L.; Nassivera, F. Consumer attitudes towards the mountain product label: Implications for mountain development. J. Mt. Sci. 2021, 18, 2255–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldesouky, A.; Mesías, F.J.; Elghannam, A.; Gaspar, P.; Escribano, M. Are packaging and presentation format key attributes for cheese consumers? Int. Dairy J. 2016, 61, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscopo, A.; Zappia, A.; De Bruno, A.; Pozzo, S.; Limbo, S.; Piergiovanni, L.; Poiana, M. Use of biodegradable materials as alternative packaging of typical Calabrian Provola cheese. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 21, 100351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammarelle, A.; Viscecchia, R.; Bimbo, F. Intention to Purchase Milk Packaged in Biodegradable Packaging: Evidence from Italian Consumers. Foods 2021, 10, 2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreafico, C.; Russo, D. A sustainable cheese packaging survey involving scientific papers and patents. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versino, F.; Ortega, F.; Monroy, Y.; Rivero, S.; López, O.V.; García, M.A. Sustainable and Bio-Based Food Packaging: A Review on Past and Current Design Innovations. Foods 2023, 12, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silayoi, P.; Speece, M. The importance of packaging attributes: A conjoint analysis approach. Eur. J. Mark. 2007, 41, 1495–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidali, K.L.; Capitello, R.; Manurung, A.J. Development and Validation of the Perceived Authenticity Scale for Cheese Specialties with Protected Designation of Origin. Foods 2021, 10, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braghieri, A.; Pacelli, C.; Riviezzi, A.M.; Di Cairano, M.; Napolitano, F. Promoting the direct sale of pasta filata cheese. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 7334–7343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Trana, A.; Sabia, E.; Di Rosa, A.R.; Addis, M.; Bellati, M.; Russo, V.; Dedola, A.S.; Chiofalo, V.; Claps, S.; Di Gregorio, P.; et al. Caciocavallo Podolico Cheese, a Traditional Agri-Food Product of the Region of Basilicata, Italy: Comparison of the Cheese’s Nutritional, Health and Organoleptic Properties at 6 and 12 Months of Ripening, and Its Digital Communication. Foods 2023, 12, 4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU Regulation No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the provision of food information to consumers. Off. J. Eur. Union 2011, 304, 18–63.

- Gokani, N.; Garde, A. Front-of-pack nutrition labelling: Time for the EU to adopt a harmonized scheme. Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 33, 751–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.A.; House, L.; Bi, X. Food outlet choice patterns of alternative food system consumers. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2023, 26, 729–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markidou, A.; Michis, A. Channel Concentration and Retail Prices: Evidence from the Traditional Cheese Market of Cyprus. 2016, 14, 109–119. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2016, 14, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, I.P. The impact of private label foods on supply chain governance. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 1106–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assolatte A Quota Delle MDD Nelle Categorie—ANALISI DEI MERCATI LATTIERO CASEARI. Available online: https://mercati.assolatte.it/201803/08-La-quota-delle-MDD-nelle-categorie.html (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- MASAF Piani di Controllo e Tariffari dei Prodotti DOP e IGP. Available online: https://www.masaf.gov.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/7469 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Duvaleix, S.; Emlinger, C.; Gaigné, C.; Latouche, K. Geographical indications and trade: Firm-level evidence from the French cheese industry. Food Policy 2021, 102, 102118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmenti, E.; Viola, E.; Funsten, C.; Borsellino, V. The Contribution of Geographical Certification Programs to Farm Income and Rural Economies: The Case of Pecorino Siciliano PDO. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monier-Dilhan, S.; Poméon, T.; Böhm, M.; Brečić, R.; Csillag, P.; Donati, M.; Ferrer-Pérez, H.; Gauvrit, L.; Gil, J.M.; Hoàng, V.; et al. Do Food Quality Schemes and Net Price Premiums Go Together? J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2021, 19, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boga, R.; Paül, V. ‘Because of its size, it’s not worth it!’: The viability of small-scale geographical indication schemes. Food Policy 2023, 121, 102549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciliberti, S.; Frascarelli, A.; Polenzani, B.; Brunori, G.; Martino, G. Digitalisation strategies in the agri-food system: The case of PDO Parmigiano Reggiano. Agric. Syst. 2024, 218, 103996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2015, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Nunan, D.; Birks, D.F. Marketing Research: An Applied Approach; Pearson: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 9781292103129. [Google Scholar]

- Di Vita, G.; Califano, G.; Raimondo, M.; Spina, D.; Hamam, M.; D’Amico, M.; Caracciolo, F. From Roots to Leaves: Understanding Consumer Acceptance in Implementing Climate-Resilient Strategies in Viticulture. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2024, 1, 8118128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vita, G.; Pippinato, L.; Blanc, S.; Zanchini, R.; Mosso, A.; Brun, F. Understanding the role of purchasing predictors in the consumer’s preferences for PDO labelled honey. J. Food Prod. Mark 2024, 27, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).