Abstract

Tourism can influence residents’ well-being in both positive and negative ways. Therefore, it is important to understand the nature of these effects and propose directions for future research from the residents’ perspective of positive tourism. This paper introduces a conceptual framework and proposes theoretical foundations and methods for exploring the impacts of tourism on residents’ well-being. It also aims to contribute to the development of tourism practices that promote well-being for all stakeholders, with a clear emphasis on resident well-being, ensuring that tourism benefits are shared between visitors and the communities they visit.

1. Introduction

Tourism is often associated with providing positive emotions and enhancing well-being, as studied within the framework of positive psychology [1]. For tourists, exploring new places, experiencing different cultures, and engaging in leisure activities are closely linked to feelings of joy, relaxation, and fulfillment [2,3]. However, the impact of tourism extends beyond visitors; it also affects the emotional and psychological landscape of residents in host destinations. The concept of positive tourism was initially introduced to benefit both tourists and host communities [4,5]. Despite the prevalent focus on tourists’ experiences in the existing literature, there is a growing need to investigate how tourism influences the well-being of residents, as their quality of life is central to the sustainability and legitimacy of tourism development.

Recent findings from the Gallup World Poll indicate that global well-being levels are under pressure, with significant declines in various regions around the world [6]. Factors such as economic instability, political unrest, environmental degradation, and social isolation contribute to this downward trend [7]. These developments highlight the urgent need for integrated strategies that help mitigate negative impacts on individuals and communities. Tourism, when planned responsibly, can play a role in fostering community well-being and strengthening the conditions for human flourishing.

Positive psychology has emerged as a transformative field of study, offering valuable insights into what constitutes human well-being [1]. By exploring dimensions such as positive emotions, meaning, relationships, engagement, and accomplishment, it provides a framework for understanding and improving individual and community quality of life. Recent advances in this field have expanded its application to include community-level well-being [5]. Tourism can both positively and negatively influence residents’ well-being, health, and social cohesion [8]. Therefore, it is important to understand the nature of these effects and to introduce a conceptual framework for future research from the residents’ perspective of positive tourism. These insights are essential for designing policies that contribute to more resilient and equitable destination communities.

Tourism can have several positive effects on the well-being of residents in host communities. Economic benefits, such as job creation and increased income, are often the most immediate and tangible advantages [9,10]. However, the positive impacts extend beyond economics to include improvements in infrastructure, heightened cultural pride, and the strengthening of social networks and civic engagement [11,12,13]. These benefits support long-term quality of life and contribute to the multidimensional well-being of residents. Understanding and enhancing these positive effects is essential for creating tourism strategies that are not only economically viable but also socially just and environmentally responsible.

This paper explores the potential pathways through which tourism influences residents’ well-being, with particular emphasis on the positive contributions of tourism. By introducing a conceptual framework and proposing theoretical foundations and methods for future research, this paper highlights the importance of addressing both the positive and negative impacts of tourism on residents. The ultimate aim is to support the development of tourism practices that promote the well-being of all stakeholders, placing resident well-being at the center of sustainable tourism development and ensuring that tourism benefits are fairly shared between visitors and host communities.

2. Literature Review

Tourism has traditionally been viewed through the lens of its economic benefits, often being celebrated for its potential to generate substantial revenue, improve tax income, and raise the standard of living in destination communities [10,14]. The influx of tourists can indeed stimulate local economies through job creation, increased income, and infrastructure development. However, these benefits are not always evenly distributed, and the economic gains brought by tourism can also introduce significant challenges for residents [15]. For example, increased demand can lead to higher living costs and inflated prices for goods and services, making it difficult for local residents to afford their daily needs. Moreover, reliance on seasonal employment can create economic instability, leading to fluctuations in income and job security [16,17]. These economic disparities can contribute to social tensions and reduce the overall well-being of residents, highlighting the complex relationship between tourism and local economies [18,19].

Tourism’s influence extends beyond the economic sphere, significantly impacting the socio-cultural fabric of destination communities. The development of tourism often brings changes to residents’ beliefs, values, daily routines, and social structures, sometimes leading to the erosion of cultural traditions and the rise in social issues such as crime, overcrowding, and conflict [20]. These changes can be particularly detrimental to minority and underserved communities, where the cultural and environmental fabric is most vulnerable to external influences [21]. As tourism grows, the social dynamics within communities can shift, sometimes leading to the commodification of culture and the loss of cultural identity. This erosion of cultural values can create a disconnect between residents and their heritage, reducing the cultural richness of the community and affecting residents’ sense of belonging and identity [11,22].

The environmental impacts of tourism are another critical area of concern, as tourism activities can lead to significant ecological degradation. Increased tourist activity often results in pollution, deforestation, and the destruction of wildlife habitats, which can have long-lasting effects on the local environment [23,24]. Large-scale tourism projects, in particular, may displace local cultures and natural environments, altering the character of destinations in ways that prioritize visitor satisfaction over community needs such as sustainability and environmental protection [25]. These environmental changes not only affect the physical landscape but also diminish residents’ quality of life and their attachment to place. The loss of green spaces and natural resources can reduce both mental and physical well-being, as residents are deprived of the benefits these environments typically provide [12,26].

Tourism has a complex and multifaceted impact on the health of residents, encompassing both positive and negative outcomes. On the positive side, tourism can contribute to better health through the enhancement of psychological well-being. Positive interactions with tourists and participation in tourism activities often generate memorable experiences, which can boost residents’ mood, reduce stress, and foster a sense of community cohesion [27,28]. Moreover, the positive emotions associated with these experiences have been shown to strengthen social connections, enhancing social engagement and interpersonal trust. These social benefits are crucial, as strong social relationships are linked to improved health outcomes and longevity, including reduced susceptibility to diseases, better cardiovascular health, and increased resilience against stress-related illnesses [29,30]. However, tourism can also pose health risks, particularly when it leads to overcrowding, which can increase stress levels among residents. The transmission of illnesses and heightened traffic accidents are additional concerns, especially in the context of global health problems like the COVID-19 pandemic [31,32,33]. These negative effects underscore the importance of a balanced approach to tourism that maximizes health benefits while mitigating potential harm.

Tourism’s influence on residents’ well-being is equally significant, with both positive and negative dimensions. Tourism activities are inherently experiential and can create opportunities for residents to engage in meaningful social exchanges with tourists, fostering a sense of community and mutual respect [34,35]. These interactions can lead to increased life satisfaction and a greater sense of belonging within the community [36]. Furthermore, the emotional connections formed through tourism can enhance social inclusiveness and compassion, contributing to the overall well-being of residents [37,38]. However, the influx of tourists can also bring challenges, such as cultural clashes, increased cost of living, and strain on local resources, which may negatively affect residents’ well-being [39]. These complex dynamics highlight the need for sustainable tourism practices that prioritize the well-being of residents, ensuring that tourism enhances rather than detracts from their quality of life. Understanding these impacts is essential for developing tourism strategies that do not simply aim for economic growth, but for lasting well-being and equity [40,41].

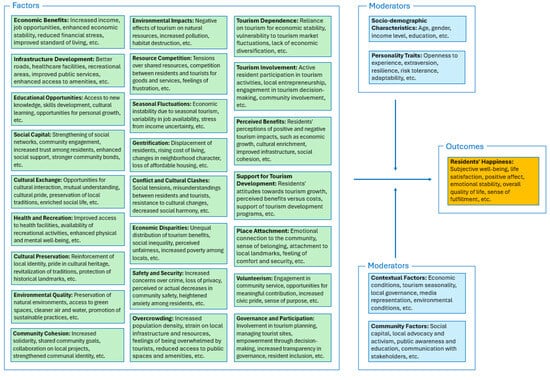

Residents’ well-being is influenced by various factors related to tourism, each with its distinct impacts (Table 1). Economic benefits, such as increased employment and income, contribute to financial stability, reducing stress and enhancing life satisfaction. Cultural exchange through tourism provides opportunities for residents to engage with new ideas and practices, fostering a sense of global connectedness and enriching their lives. Infrastructure development, including improvements in roads, healthcare, and recreational facilities, enhances residents’ quality of life by providing better access to essential services and leisure activities. Strengthening social capital and community cohesion through tourism builds trust and cooperation among residents, further enhancing well-being. However, negative factors such as stress from overcrowding, resource competition, and economic disparities can detract from residents’ well-being. These factors highlight the importance of a comprehensive approach to tourism development that considers both the positive and negative impacts on local communities, ensuring that tourism contributes meaningfully to the overall well-being of residents [18,39].

Table 1.

The factors influencing residents’ well-being.

There is a clear need for comprehensive research into the pathways through which tourism influences residents’ well-being. Establishing robust theoretical foundations and developing integrative conceptual frameworks are essential steps in guiding future studies in this area. By exploring the complex interplay between tourism and residents’ well-being—using both subjective and objective indicators—researchers can identify strategies to enhance tourism’s positive contributions while minimizing its adverse effects. This research is vital for advancing sustainable tourism practices that place resident well-being at the center of development efforts, ensuring that the benefits of tourism are shared equitably and contribute to long-term community resilience [18,43]. Such research also supports the goals of a well-being economy and intergenerational equity by informing evidence-based policies that improve quality of life across time and population groups. A more balanced and sustainability-oriented approach to tourism development requires ongoing empirical investigation grounded in multidisciplinary theory.

3. Theoretical Foundations for Exploring the Impacts of Tourism on Residents’ Well-Being

Several theoretical frameworks from positive psychology, social psychology, environmental psychology, and sustainability science provide a robust foundation for exploring the impacts of tourism on residents’ well-being (Table 2). These frameworks offer multidimensional insights into how tourism affects emotional, social, environmental, and economic aspects of life in local communities.

Table 2.

Theoretical frameworks.

The PERMA model from positive psychology identifies five core components of well-being: Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment [47]. Each dimension can be applied to tourism contexts. Positive Emotion may result from leisure, cultural activities, and improved amenities. Engagement refers to residents’ active involvement in tourism planning and events that match their interests and skills. Relationships are built through interactions with visitors and community participation, enhancing trust and cohesion. Meaning is derived from preserving and sharing culture, nature, and identity through tourism. Accomplishment reflects pride and recognition gained from contributing to tourism success. Together, these dimensions help evaluate how tourism supports or undermines psychological and social well-being at the community level.

The Bio-Psycho-Social model offers a holistic view by integrating biological, psychological, and social influences on well-being. In tourism, biological impacts may include improved or worsened health due to environmental changes or access to infrastructure. Psychologically, tourism can reduce or increase stress, depending on the balance of benefits and pressures such as overcrowding or economic gain [50,67]. Socially, tourism may either strengthen or disrupt community ties and social equity [68].

The Broaden-and-Build Theory [52] suggests that positive emotions expand residents’ outlook and build long-term personal and social resources. Tourism experiences that foster joy, pride, and curiosity can help develop resilience and adaptability in communities. Similarly, Flow Theory [53] describes optimal engagement when individuals are deeply absorbed in meaningful activity. Residents who find personal relevance and challenge in tourism-related roles—such as guiding, hosting, or organizing—may experience flow, contributing to their long-term satisfaction and empowerment.

The Happiness Model [55] and Authentic Happiness Theory [47] emphasize the combination of pleasure, engagement, and meaning. These models imply that residents benefit most when tourism brings joy, meaningful interactions, and a sense of contribution to the community. Activities that reflect local values and encourage active involvement can improve emotional well-being and community pride [69].

Social Exchange Theory explains that residents’ attitudes toward tourism depend on perceived benefits and costs. Support is more likely when benefits such as jobs and improved services outweigh negative effects like congestion or cultural disruption [58]. Stakeholder Theory complements this by emphasizing fair value distribution across all stakeholders, including residents [60]. These theories highlight the need for inclusive planning processes that respect and empower communities [70].

Social Capital Theory focuses on the role of networks, trust, and civic participation in shaping well-being. In tourism, strong community ties and shared goals can amplify positive impacts, while weak networks may exacerbate conflict or exclusion [62]. Place Attachment Theory explores the emotional connection people feel to their environment. Tourism that aligns with local identity can strengthen place attachment, while disruption to familiar settings may provoke resistance or loss [64].

To complement psychological and social theories, sustainability science offers the capitals approach, which considers human, natural, social, and economic capital as foundations for current and future well-being. Tourism should be evaluated not only by immediate outcomes but by its effect on these capital stocks over time [11]. This perspective is essential for achieving intergenerational equity, where today’s tourism development does not compromise the well-being of future generations [18].

Together, these theories offer a comprehensive framework for analyzing how tourism affects resident well-being across multiple domains. They emphasize the importance of balancing short-term experiences with long-term sustainability, integrating subjective and objective indicators, and prioritizing local voices in tourism development.

4. Measuring the Impacts of Tourism on Residents’ Well-Being

Traditionally, the impact of tourism has been measured using economic indicators derived from border statistics and accommodation data, such as tourist arrivals, overnight stays, and visitor expenditures. These metrics are often analyzed through Input–Output models and Tourism Satellite Account statistics to assess direct, indirect, and induced economic effects [71]. However, this approach prioritizes economic outcomes while often overlooking the broader social, environmental, and psychological impacts on local residents [72]. There is growing recognition of the need to shift toward human-centered measures that reflect quality of life and overall well-being.

To assess tourism’s effects on resident well-being, secondary data sources offer valuable macro-level insights. The World Happiness Report provides cross-national comparisons of well-being indicators that can reveal associations between tourism development and community satisfaction [73]. The Gallup World Poll collects subjective well-being data globally, offering trends relevant to tourist regions [6]. The Human Development Index (HDI), published by the UNDP, contextualizes tourism within broader social progress [74]. Similarly, the OECD Better Life Index evaluates well-being across multiple dimensions such as health, environment, and community, aligning closely with resident-centered tourism goals [45]. Additional sources like the Eurobarometer and Happy Planet Index offer insights into public attitudes and sustainable well-being [75,76].

Primary data collection is essential for directly evaluating residents’ lived experiences of tourism. Validated tools, such as the Satisfaction with Life Scale [77], assess global life satisfaction, while Positive Emotion Scales capture the frequency and intensity of daily emotional experiences [52]. Qualitative approaches—such as interviews and focus groups—reveal rich, contextual narratives about tourism’s perceived benefits and burdens in specific communities [78]. These methods uncover emotional and cultural nuances that may not be visible through standardized surveys.

Given the complex nature of tourism’s impacts, a mixed-methods approach is recommended. This involves combining quantitative indicators with qualitative insights to evaluate both objective and subjective dimensions of well-being. New scale development, particularly instruments tailored to tourism-specific impacts on local communities, can enhance reliability and validity [79]. By triangulating multiple data sources and tools, researchers can better classify destination types, assess social sustainability, and inform evidence-based tourism policies.

Sentiment analysis of social media is a growing method for assessing resident attitudes toward tourism in real time. This technique categorizes online content—posts, comments, and hashtags—into positive or negative sentiments to identify emotional responses to tourism [80]. Such analysis helps detect areas of satisfaction or discontent, offering feedback loops for policymakers and developers seeking to improve tourism’s alignment with community values.

Experimental methods provide a powerful tool to evaluate the causal impacts of specific tourism interventions. Controlled experiments can test how improvements in infrastructure, communication, or resident participation influence well-being outcomes [81]. These methods support rigorous policy experimentation and help identify which actions genuinely enhance resident satisfaction, community cohesion, or long-term quality of life.

5. Conclusions

Tourism can influence residents’ well-being through a range of interconnected pathways—economic, socio-cultural, environmental, and psychological. Positive impacts, such as job creation, improved infrastructure, cultural revitalization, and strengthened social capital, can enhance residents’ quality of life. At the same time, tourism can introduce challenges, including overcrowding, rising living costs, environmental degradation, and threats to cultural integrity. These diverse effects underscore the complexity of tourism’s role in shaping community well-being and highlight the need for multidimensional evaluation frameworks that move beyond economic growth.

A conceptual model of positive tourism from the residents’ perspective should place resident well-being as the primary outcome variable, rather than treating it as an incidental byproduct (Figure 1). Independent variables may include economic benefits, cultural exchange, environmental quality, governance, and social cohesion—factors shown to impact both subjective and objective well-being. These relationships should be analyzed in light of moderating variables such as residents’ socio-demographic characteristics, value orientations, and cultural norms, as well as contextual features like the intensity of tourism activity, institutional capacity, and capital stock levels (human, social, economic, and natural).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

This approach aligns with recent calls in the literature to treat resident well-being as a sustainability indicator, rather than relying solely on tourist satisfaction or GDP growth [11,18]. Moreover, it supports the principles of intergenerational equity, ensuring that tourism development contributes positively not just to current residents, but also to future generations. Tourism policies and strategies should be based on inclusive, evidence-informed frameworks that evaluate long-term outcomes and prioritize community needs. By doing so, tourism can evolve into a genuinely well-being-centered and sustainable development pathway, fostering equitable benefits for all stakeholders involved.

Several theoretical frameworks—including the PERMA model, the Bio-Psycho-Social model, Broaden-and-Build theory, Flow theory, and the Capitals Approach—offer essential insights into how tourism affects residents’ well-being. These models highlight the importance of considering emotional, psychological, social, and environmental dimensions, as well as the systems that sustain long-term quality of life. They collectively emphasize that well-being is not merely the absence of dissatisfaction, but the presence of meaningful engagement, social connection, empowerment, and environmental harmony. Applying these frameworks enables researchers to better interpret the multifaceted and dynamic nature of tourism’s impact on local communities.

Measuring residents’ well-being requires a multi-method approach that integrates subjective experiences with objective indicators. Secondary data from tools, such as the World Happiness Report, Gallup World Poll, OECD Better Life Index, and Human Development Index, provide a macro-level view of social trends and interregional comparisons. Primary data collection through surveys (e.g., life satisfaction and positive emotion scales), interviews, and focus groups reveals individual and community-level perceptions that inform local policy. In addition, digital tools such as sentiment analysis of social media and participatory research methods offer timely, location-specific feedback. The use of both traditional and innovative data sources reflects a growing shift toward evidence-based, well-being-centered tourism planning.

The insights drawn from this research have direct and significant implications for policy and destination management. Recognizing that residents’ well-being is a key indicator of tourism sustainability, planners must move beyond narrow economic measures and design inclusive strategies that reflect the aspirations, values, and capacities of local communities. This includes fostering equitable benefit distribution, protecting natural and cultural assets, and enabling meaningful resident participation in decision-making. Policies informed by well-being indicators are more likely to generate long-term support for tourism, enhance social cohesion, and contribute to community resilience.

Future research should deepen the exploration of tourism’s effects on resident well-being using both established and emerging methodologies. Longitudinal studies, community-based experiments, and big data analytics can shed light on causal relationships and identify scalable best practices. Scholars should also advance the development of destination well-being indices that incorporate both subjective evaluations and capital-based indicators (e.g., natural, social, and human capital). In doing so, researchers and policymakers can work together to ensure that tourism not only thrives economically but also contributes meaningfully to the well-being of current and future generations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G., A.F. and A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT 4o for the purposes of proofreading and language refinement. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Seligman, M.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology: An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.; Moyle, B.D.; Dupre, K.; Filep, S.; Vada, S. Progress in research on seniors’ well-being in tourism: A systematic review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2022, 44, 101040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Zheng, D.; Hou, H.; Phau, I.; Wang, W. Tourism as a dementia treatment based on positive psychology. Tour. Manag. 2022, 92, 104556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schänzel, H. Positive Tourism; Filep, S., Laing, J., Csikszentmihalyi, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, M. Moving from positive psychology to positive tourism: A conceptual approach. In Tourism, Hope and Happiness; Singh, T.V., Butler, D., Fennell, D.A., Eds.; Aspects of Tourism; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup. The Global Rise of Unhappiness. 2022. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/401216/global-rise-unhappiness.aspx (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Clifton, J. Blind Spot: The Global Rise of Unhappiness and How Leaders Missed It; Gallup Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Godovykh, M.; Hacikara, A.; Baker, C.; Fyall, A.; Pizam, A. Measuring the perceived impacts of tourism: A scale development study. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 27, 2516–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tour. Manag. 2018, 63, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.E. Estimating the economic impacts of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 592–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L. Resident well-being and sustainable tourism development: The ‘capitals approach’. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 2119–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L. Tourism development to enhance resident well-being: A strong sustainability perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H. Perceived social impacts of tourism and quality-of-life: A new conceptual model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetanah, B. Assessing the dynamic economic impact of tourism for island economies. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M.; Ridderstaat, J.; Fyall, A. The well-being impacts of tourism: Long-term and short-term effects of tourism development on residents’ happiness. Tour. Econ. 2023, 29, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Hussain, K.; Kannan, S. Positive vs negative economic impacts of tourism development: A review of economic impact studies. In Proceedings of the 21st Asia Pacific Tourism Association Annual Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 14–17 May 2015; pp. 405–413. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H.L. Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L. Tourism Development in a Wellbeing Economy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.; Pratt, S.; Movono, A. Tourism, poverty alleviation and economic inequality: Fiji case study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 889–907. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, R. Tourism, Tourists and Society, 5th ed; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Massing, D. The impact of tourism on minority and underserved communities: A critical review. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1617–1634. [Google Scholar]

- Pung, J.M.; Gnoth, J.; Del Chiappa, G. Tourist experience, value creation and the role of affective experiences in tourists’ well-being. Tour. Manag. 2020, 76, 103952. [Google Scholar]

- Postma, A.; Schmuecker, D. Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: Conceptual model and strategic framework. J. Tour. Futures 2017, 3, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutty, M.; Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C. The global effects and impacts of tourism. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and Sustainability; Hall, C., Gossling, S., Scott, D., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 36–62. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.; Bao, J. Displacement of residents and changes in the cultural landscape: Case study of a tourism community. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 5, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Y. Environmental impacts of tourism and residents’ well-being: A study on the coastal areas of China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8813. [Google Scholar]

- Godovykh, M.; Ridderstaat, J. Health outcomes of tourism development: A longitudinal study of impact perceptions. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104157. [Google Scholar]

- Godovykh, M.; Ridderstaat, J.; Fyall, A. The well-being impacts of tourism: A critical review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100811. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm, J.K.; Kubzansky, L.D. The heart’s content: The association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 138, 655–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chida, Y.; Steptoe, A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: A quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosom. Med. 2008, 70, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M.; Pizam, A.; Bahja, F. Antecedents and outcomes of health risk perceptions in tourism, following the COVID-19 pandemic. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamata, H. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourism and residents’ well-being in Japan. Tour. Geogr. 2021, 23, 541–550. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Ryan, C.; Zhang, X. Health, well-being and happiness in tourism: A systematic review and research agenda. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 56, 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, S.; Scarles, C.; Cohen, S.; Adams, P. Measuring memorable tourism experiences: Conceptual and practical issues. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Tung, V.W.S.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Exploring the essence of memorable tourism experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1367–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M.; Fyall, A.; Pizam, A. Handbook on Tourism, Public Health and Wellbeing. In Positive Health Impacts of Tourism; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 124–138. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio, J.F.; Gaertner, S.L.; Kawakami, K.; Hodson, G. Why can’t we just get along? Interpersonal biases and interracial distrust. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2002, 8, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.R.; Schweitzer, M.E. Feeling and believing: The influence of emotion on trust. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 88, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shani, A.; Uriely, N. The impacts of overtourism on the quality of life of residents in tourist cities: A comparison of two case studies. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 1363–1379. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, L. Measuring the Sustainability of Tourism (SF-MST): New Wine in an Old Bottle? Sustainability 2024, 16, 5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, H.; Uysal, M. Life satisfaction and support for tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.A. Volunteering and happiness: Examining the differential effects of volunteering types according to household income. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 795–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, A.G.; Martin, D. Comprehensive research methods for exploring residents’ happiness and well-being in tourism destinations. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 1037–1052. [Google Scholar]

- McKercher, B.; Chon, K. The over-commercialization of tourism experiences. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Better Life Index. 2024. Available online: https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/ (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Seligman, M.E.P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. Atria Books: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.P. The Hope Circuit: A Psychologist’s Journey from Helplessness to Optimism. PublicAffairs: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. From biomedical to biopsychosocial: Being scientific in the human domain. Psychosomatics 1997, 38, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, D.T.; Halligan, P.W. The biopsychosocial model of illness: A model whose time has come. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. What good are positive emotions? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Positive emotions broaden and build. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 47, 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shahar, T. Happier: Learn the Secrets to Daily Joy and Lasting Fulfillment; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shahar, T. Happier, No Matter What: Cultivating Hope, Resilience, and Purpose in Hard Times; The Experiment: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; John Wiley & Sons Inc: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Nunkoo, R.; Gursoy, D. Residents’ support for tourism: An identity perspective. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 699–711. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C. Stakeholder Theory: Concepts and Strategies; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J., Ed.; Greenwood:: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, I.; Low, S.M. Place Attachment; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. The psychology of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 74, 101528. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.F. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J.P. The Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress Revisited; OFCE: Paris, France, 2009; Volume 33, pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, J.; Gomes, S.; Gonçalves, F. The interplay between tourism, health, and well-being: A perspective from Portugal. J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 8, 72–83. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfeld, Y.; Kay, C. Residents’ support for sustainable tourism development: The role of perceived sustainability. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 1347–1363. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Perdue, R. Handbook of Tourism and Quality-of-Life Research: Enhancing the Lives of Tourists and Residents of Host Communities, 2nd ed; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mowforth, M.; Munt, I. Tourism and Sustainability: Development, Globalisation and New Tourism in the Third World, 5th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baggio, R. The Future of Tourism. In Measuring Tourism: Methods, Indicators, and Needs; Eduardo, F.S., Chris, C., Eds.; Springer Cham: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilo, E.; Rosselló, J.; Vila, M. Length of stay and daily tourist expenditure: A joint analysis. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 21, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Happiness Report 2024. Available online: https://worldhappiness.report/ (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Human Development Report 2023–2024. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2023-24 (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- European Commission. Eurobarometer. 2024. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/about/eurobarometer (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Happy Planet Index. How Happy is the Planet? 2024. Available online: https://happyplanetindex.org/ (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. Social media sentiment and public opinions on tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2019, 73, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).