4.2.3. Hypotheses Testing

First, the model fit index test is carried out. In the hypothesis testing model fit index table, CMIN/DF is 2.885, less than 3, and its GFI, AGF, and NLI are 0.865, 0.838, 0.886, respectively, greater than 0.8 and less than 0.9, in the acceptable range. TLI and CFI are 0.913 and 0.922, respectively, and the RMSEA is <0.08, indicating that the model fit is acceptable.

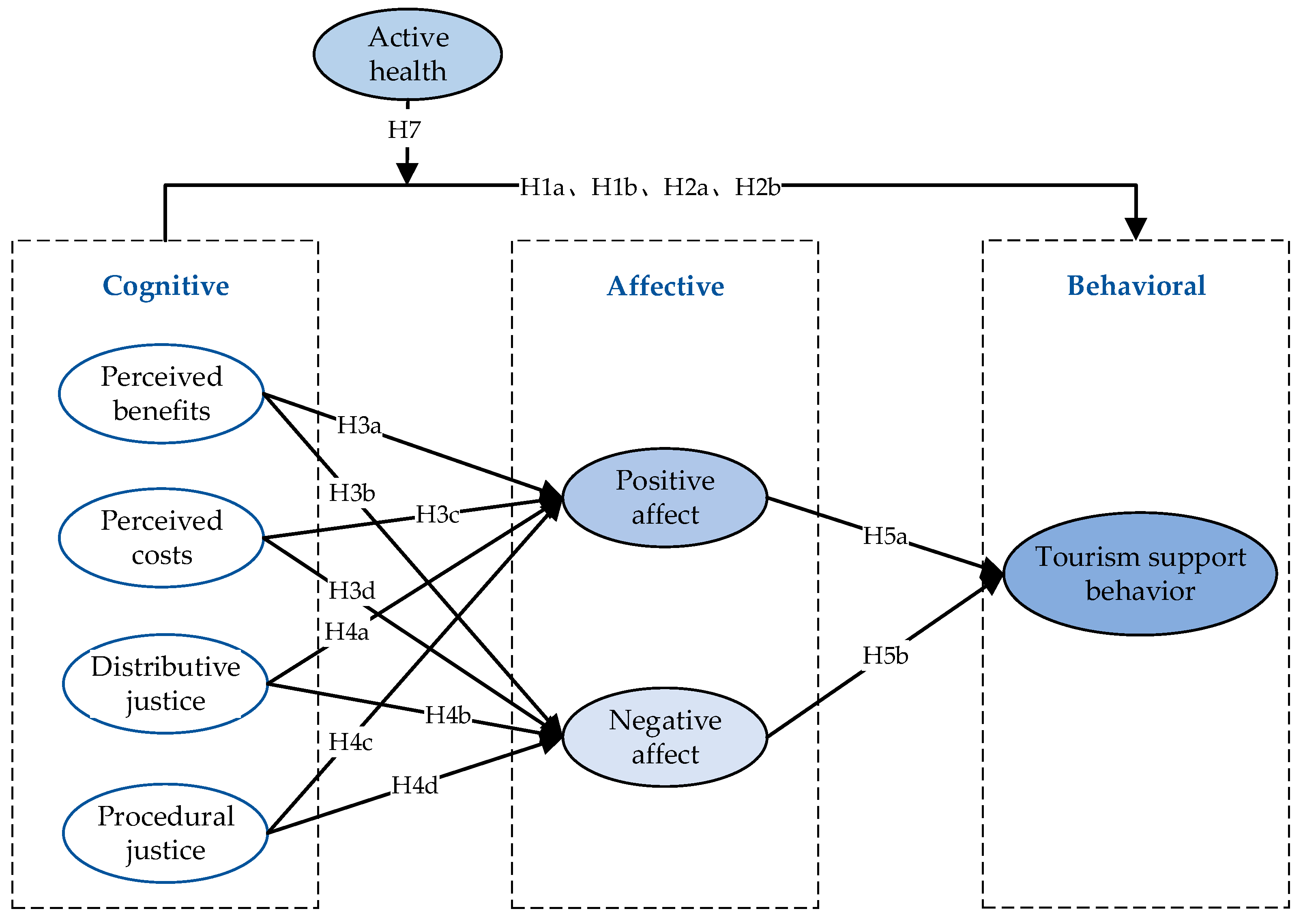

The paper analyzed the model’s main effects using Amos24.0 software. The test results show that the standardized path coefficients of perceived benefits, perceived costs, distributive justice, and procedural justice on tourism support behavior are 0.133, −0.142, 0.153, and 0.243, respectively, which pass the significance level test, and the hypotheses H1a, H1b, H2a, and H2b are true. The standardized path coefficient of positive affect on tourism support behavior is 0.265,

p < 0.001, which passes the significance level test, and positive affect has a significant positive effect on tourism support behavior. Hypothesis H5a is established. The standardized path coefficient of negative affect on tourism support behavior is −0.124,

p > 0.05, which does not pass the significance level test, and hypothesis H5b is not established. This paper attempts to explain the findings of Zhang [

60] and other scholars on the behavioral effects of relative deprivation (a kind of negative psychology and affect). It has been found that relative deprivation, as a negative affect, usually leads to negative attitudes and behaviors. However, it can sometimes lead to positive behaviors. This is because residents behave differently after experiencing negative affect, depending on their attributional style and self-efficacy. The conclusion of this study also applies to our research. Even if negative emotions are perceived, tourism destination residents may generate support behaviors by considering the impacts of their own perceived benefits, ability to participate, local cultural identity, prospects for health and wellness tourism development, and positive coping factors. In the pre-survey and on-site interviews, it was found that some residents do not know much about the development of health and wellness tourism, and their affect is in a neutral state. Although there are certain forms of negative affect, such as a low degree of participation, a marginalized position, and a certain sense of exclusion and deprivation, the majority of residents still expressed a high degree of tolerance and support for the development of local health and wellness tourism within an acceptable range. The overall reason for this is related to the wait-and-see attitude of the residents towards the new industry at the early stage of development and their degree of tolerance.

The mediating effect test was still conducted using Amos24.0 software, using the bootstrap method, with the sample size set at 2000 and the confidence interval for bias correction set at 95%. Negative affect does not mediate between the cognitive dimensions and tourism support behavior because of the different primary paths of negative affect to tourism support behavior. Therefore, only the mediating role of positive affect between the dimensions of perception and tourism support behavior was measured in this paper. The results of data analysis showed that the confidence intervals of the indirect effects of perceived benefit, perceived cost, distributive justice, and procedural fairness on tourism support behavior for bias-corrected 95% CI and percentile 95% CI were [0.050, 0.321] and [0.045, 0.197], [−0.261, −0.043] and [−0.255, −0.040], [0.019, 0.100] and [0.019, 0.099], [0.031, 0.166] and [0.026, 0.156], respectively, none of which contained zeros and the indirect effects were all significant. The direct effect interval of perceived benefit on tourism support behavior was not significant, and the direct effect of perceived cost, distributive justice, and procedural justice on tourism support behavior was significant. Therefore, positive affect plays a fully mediating role between perceived benefit and tourism support behavior and a partially mediating role between perceived cost, distributive justice, procedural fairness, and tourism support.

In this study, the moderating effect of active health on residents’ cognitive predictive behavior was examined by the stratified regression method through SPSS24.0 software, and the moderating effect was examined by the significance of the coefficients of the interaction terms between active health and residents’ cognition in each dimension.

- (1)

Moderating effect of active health in perceived benefits and tourism support behavior

Moderation tests were conducted using stratified regression analysis with the inclusion of control variables such as demographic information in the first stratum and the independent variable perceived benefit and the moderator variable active health in the second stratum. The relationship between perceived benefit and tourism support behavior was significant, R2 = 0.508, and with the inclusion of an interaction term between the independent and moderator variables int_1 in the third stratum of the model, R2 = 0.509 and R2 = 0.001. This shows that the incremental contribution of the interaction term is very weak; from the coefficient results, the interaction term predicts the dependent variable beta = −0.002, and

p = 0.566 shows that the model prediction fails. Active health is not a moderating variable for the perceived benefits to predict tourism support behavior; the results are shown in

Table 7. The reason why active health is not a moderating variable in the relationship between perceived benefit and tourism support behavior may be that in the process of recreation and wellness tourism development, the residents’ perception of benefit does not change due to differences in individual active health levels. Combined with the interview exchanges during the questionnaire process, it was discovered that the majority of residents are in a marginal position in the process of development of health and wellness tourism, with a low awareness of participation and a low level of participation, and that the overall residents’ perceptions of benefit are roughly the same. Therefore, even though the residents’ active health levels are different, the perception of benefit is roughly the same, and the relationship between perceived benefit and supportive behaviors does not change significantly and therefore does not have a moderating effect.

- (2)

Moderating role of active health in perceived costs and tourism support behavior

The moderation test was conducted using a hierarchical regression analysis, with the inclusion of control variables such as demographic information in the first level and the inclusion of the independent variable perceived cost and the moderating variable active health in the second level. The relationship between perceived cost and tourism support behavior was significant, R2 = 0.517, and with the inclusion of an interaction term int_2 for the independent and moderating variables in the third level of the model, R2 = 0.541 and R2 = 0.024. This shows that the incremental contribution of the interaction term exists, and from the coefficient results, the interaction term predicts the dependent variable beta = 0.157, and

p = 0.000 shows that the model prediction is successful and active health is the moderating variable of perceived costs in predicting tourism support behavior; the results are shown in

Table 8.

As seen in

Table 8, the interaction term int_2 regression coefficients are significantly positive, and perceived costs and tourism support behavior are significantly negative, indicating that the moderating variable (active health) attenuates the negative impacts of perceived costs on tourism support behavior. Active health has a significant inhibitory effect on the relationship between perceived costs and tourism support behavior. That is, the higher the level of residents’ active health, the smaller the negative effect of residents’ perceived costs on tourism support behavior. Hypothesis H7 is valid. The higher the level of active health of residents, the more they are exposed to recreational knowledge, and the higher their familiarity with health and wellness tourism, the lower their perception of risk and uncertainty, and thus the more inclusive they are of health and wellness tourism, which reduces the level of perceived costs of residents through active health impacts and ultimately promotes the formation of tourism support behaviors for recreation and wellness tourism.

- (3)

Moderating role of active health in distributive justice and tourism support behavior

The moderation test was conducted using stratified regression analysis. With the addition of control variables such as demographic information in the first stratum and the inclusion of the independent variable distributive justice and the moderating variable active health in the second stratum, the relationship between distributive justice and tourism support behavior was significant, with R2 = 0.522, and, with the addition of an interaction term of the independent and moderating variables int_3 in the third stratum of the model, with R2 = 0.531 and R2 = 0.009. This shows that the incremental contribution of the interaction term exists, and from the coefficient results, the interaction term predicts the dependent variable beta = −0.101,

p = 0.003, showing that the model prediction is successful, and active health is the moderator variable of distributive justice predicting tourism support behavior. The results are shown in

Table 9.

As seen in

Table 9, the interaction term int_3 regression coefficient is significantly negative, indicating that the moderator variable (active health) weakens the positive influence of distributive justice on tourism support behavior. Active health has a significant inhibitory effect on the relationship between distributive justice and tourism support behavior. That is, the stronger the concept of residents’ active health, the weaker the positive contribution of residents’ distributive justice to tourism support behavior. However, active health has a significant positive influence on tourism support behavior. In the process of enhancing tourism support behavior, there is a substitution relationship between active health and distributive justice.

- (4)

Moderating role of active health in procedural justice and tourism support behavior

The moderation test was conducted using stratified regression analysis with the inclusion of control variables such as demographic information in the first stratum and the independent variable procedural justice and the moderator variable active health in the second stratum. The relationship between procedural justice and tourism support behavior was significant, R2 = 0.536, and with the inclusion of the interaction term int_4 of the independent and moderator variables in the third stratum of the model, R2 = 0.544 and R2 = 0.008. This shows that the incremental contribution of the interaction term exists, and based on the coefficient results, the interaction term predicts the dependent variable beta = −0.095,

p = 0.004, showing that the model prediction is successful, and active health is the moderator variable of procedural justice in predicting tourism support behavior. The results are shown in

Table 10.

As seen in

Table 10, the interaction term int_4 regression coefficient is significantly negative, indicating that the moderator variable (active health) weakens the positive influence of procedural justice on tourism support behavior. Active health has a significant inhibitory effect in the relationship between procedural justice and tourism support behavior. That is, the stronger the level of residents’ active health, the weaker the positive contribution of residents’ procedural justice to tourism support behavior. However, active health has a significant positive effect on tourism support behavior, and in the process of enhancing tourism support behavior, there is a relationship between active health and procedural justice, i.e., a substitution relationship. Hypothesis H7 is valid.

According to the findings of (3) and (4), active health was found to have an alternative moderating role in the relationship between distributive and procedural justice and tourism support behavior. Driven by active health, residents actively maintain health and wellness tourism and participate in health and wellness activities. This allows them to directly or indirectly engage in wellness tourism activities, enriching their perception of the development of health and wellness tourism. As a result, residents generate a sense of pride and satisfaction, which contributes to the enhancement of their tourism support behaviors. These behaviors are particularly stronger with respect to external stimuli such as perceived justice. Therefore, when residents have a high level of active health, active health replaces the positive impact of perceived justice on tourism support behaviors. In this case, the positive impact of perceived justice on tourism support behaviors is weakened, indicating a substitution effect between the two variables. However, when the level of residents’ active health is low and their participation in health and wellness tourism is weak compared to those with high active health, residents are more passive in accepting external stimuli and generating tourism support behaviors.