Motivations, Quality, and Loyalty: Keys to Sustainable Adventure Tourism in Natural Destinations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Motivation in Tourism

2.2. Motivational Constructs in Adventure Tourism

2.3. Quality Perceived of the Destiny

2.3.1. Definition and Relevance

2.3.2. Economic Context, Perceived Quality, and Tourist Loyalty

2.3.3. Connection with Adventure Tourism

2.3.4. Theoretical Framework

2.4. Loyalty in Tourism

2.4.1. Conceptualization of Loyalty

2.4.2. Theoretical Foundation

2.4.3. Loyalty in Adventure Tourism

3. Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire Design

3.2. Data Analysis

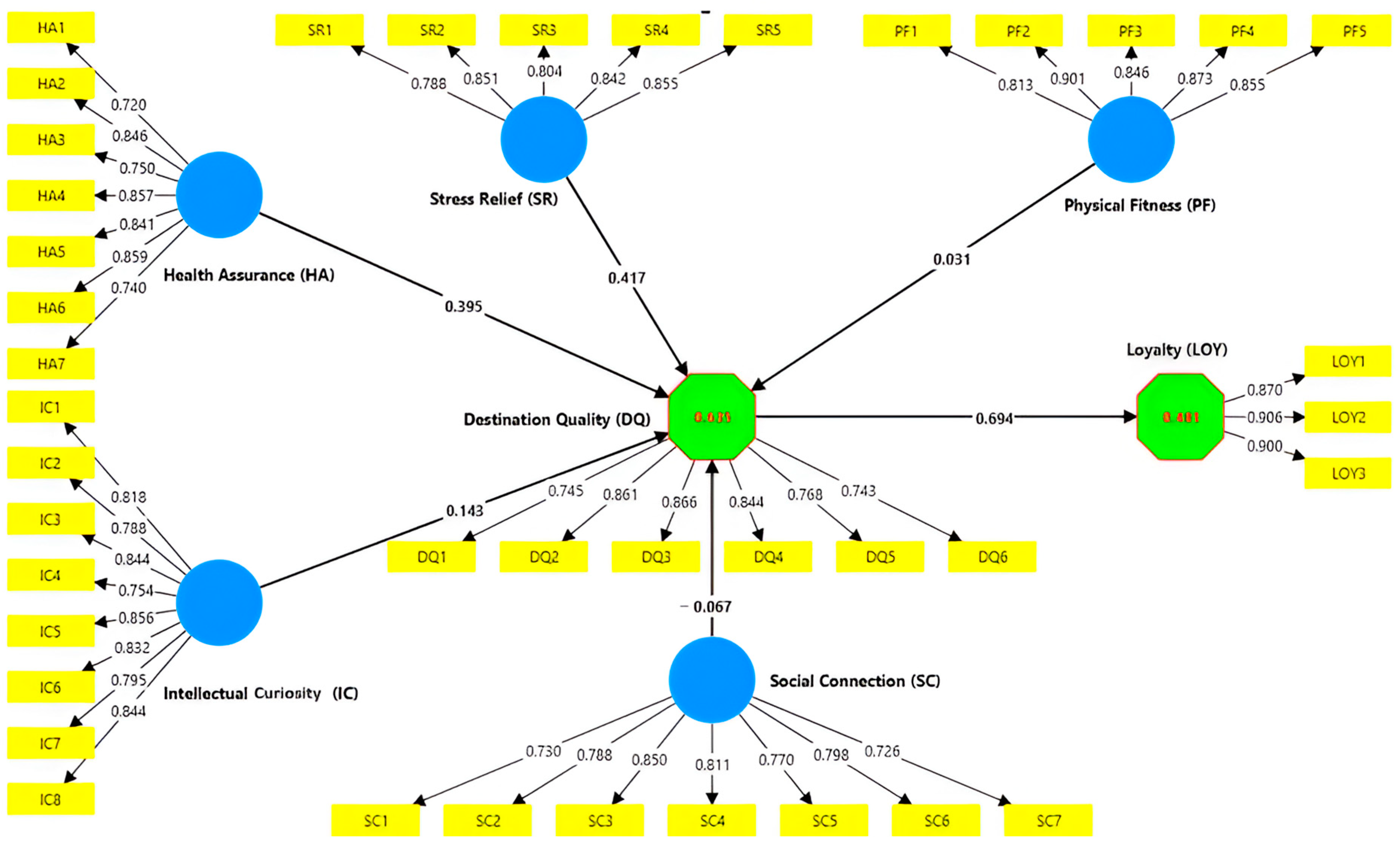

4. Results

Model of Measurement

5. Discussion

Implications

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Lines of Investigation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Janowski, I.; Gardiner, S.; Kwek, A. Dimensions of adventure tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichler, B.F.; Peters, M. Soft adventure motivation: An exploratory study of hiking tourism. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R. Nature tourism and mental health: Parks, happiness, and causation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1409–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Orden-Mejñia, M.; Reclade-Lino, X. Designing an Adventure Tourism Package from the Preferences of the Visitors. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2022, 13, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; Castillo-Canalejo, A.M. Sustainable tourism in island destinations: A study of tourist satisfaction and loyalty in the Canary Islands, Spain. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 979–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Contreras-Moscol, D.; Orden-Mejía, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Vera-Holguin, H.; Carvache-Franco, O. Motivations and Loyalty of the Demand for Adventure Tourism as Sustainable Travel. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M.A.; Croes, R.; Lee, S.H. The tourism–hospitality industry’s recovery from COVID-19: Developing a research agenda. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Nørfelt, A.; Josiassen, A.; Assaf, A.G.; Tsionas, M.G. Understanding the COVID-19 tourist psyche: The evolutionary tourism paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, N.; Alén González, M.E.; Losada, N.; Melo, M. The adoption of virtual reality technologies in the tourism sector: Influences and post-pandemic perspectives. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2024, 10, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Bedoya, V.H.; Ruiz-Palacios, M.A.; Meneses-La-Riva, M.E. Tourism entrepreneurship in Latin America: A systematic review of challenges, strategies, and post-COVID-19 perspectives. Sustainability 2025, 17, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prideaux, B.; Pabel, A. Degrowth as a strategy for adjusting to the adverse impacts of climate change in a nature-based destination. In Degrowth and Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. The future of tourism in the post-COVID-19 era: Insights from the crisis management perspective. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 1021–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, A.; Pikkemaat, B.; Dickinger, A. Unlocking sustainable tourism: Exploring the drivers and barriers of social innovation in community model destinations. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2025, 36, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Cheng, Q.; Lv, Y.; Li, N. Risk perception, travel intentions and self-protective behavior of chronically ill tourists under the protection motivation perspective. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G. Annals of Tourism Research. Clim. Risk Manag. 1981, 8, 187–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, L.N.; Pham, L.H.; Hoang, T.T.P. Applying push and pull theory to determine domestic visitors’ tourism motivations: A case study of Vietnam’s Central Highlands. J. Tour. Serv. 2023, 14, 136–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngondo, E.; Hermann, U.P.; Venter, D.H. Push and pull factors affecting domestic tourism in the Erongo region, Namibia. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2024, 53, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenosky, D.B. The “pull” of tourism destinations: A means-end investigation. J. Travel Res. 2002, 40, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih-Shuo, Y.; Tai-Ying, C.; Kuan-Ying, C.; Chen-Lin, L.; Tzung-Cheng, H. From soft to hard adventure: Examining experienced mountaineers’ mountaineering intentions through the lens of the theory of planned behavior. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2025, 50, 100865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orden-Mejía, M.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Carvache-Franco, W. Sociodemographic aspects and satisfaction of Chinese tourists visiting a coastal city. Cogent. Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2419504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, D.; Mohamed, D.N.H.S. The impact of push–pull motives on internal tourists’ visit and revisit intentions to Egyptian domestic destinations: Mediating role of country image. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaho, Y. Conceptualizing the adventure tourist as a cross-boundary learner. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 47, 100795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Tung, H. Social media engagement and impacts on post-COVID-19 travel intention for adventure tourism in New Zealand. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 44, 100612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, J.; Couto, G.; Sousa, Á.; Pimentel, P.; Oliveira, A. Idealizing adventure tourism experiences: Tourists’ self-assessment and expectations. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 35, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Alarcón, S. From netnography to segmentation for the description of the rural tourism market based on tourist experiences in Spain. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Meng, X.; Siriwardana, M.; Pham, T. The impact of COVID-19 on the Chinese tourism industry. Tour. Econ. 2022, 28, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, Q. Group Cohesion and Destination Loyalty in Wellness Tourism. J. Wellness Tour. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pomfret, G.; Sand, M.; May, C. Conceptualising the power of outdoor adventure activities for subjective well-being: A systematic literature review. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 42, 100641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, L. Psychological Benefits of Adventure Tourism. Integr. J. Res. Arts Humanit. 2024, 4, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avecillas-Torres, I.; Herrera-Puente, S.; Galarza-Cordero, M.; Coello-Nieto, F.; Farfán-Pacheco, K.; Alvarado-Vanegas, B.; Ordóñez-Ordóñez, S.; Espinoza-Figueroa, F. Nature Tourism and Mental Well-Being: Insights from a Controlled Context on Reducing Depression, Anxiety, and Stress. Sustainability 2025, 17, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H.-K.; Wu, C.-C. Effect of adventure tourism activities on subjective well-being. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 91, 103147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, T.; Zheng, J.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Shen, J. Health and Wellness Tourists’ Motivation and Behavior Intention: The Role of Perceived Value. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomfret, G.; Doran, A. Gender and mountaineering tourism. In Mountaineering Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 164–181. ISBN 9781315769202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M.J.; Tucker, H. Adventure tourism: The freedom to play with reality. Tour. Stud. 2004, 4, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, N.; Pan, C.; Wu, J.; Gou, J. The study on the relationship between perceived value, satisfaction, and tourist loyalty at industrial heritage sites. Heliyon 2024, 17, e37184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, R.; Shi Yin, C.; Neethiahnanthan, A. Tourists’ perceptions of the sustainability of destination, satisfaction, and revisit intention. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2025, 50, 106–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.; Niazi, M. Protecting natural environment of destination through tourists’ environment responsible behavior: Empirical analysis of green brand equity model. Soc. Responsib. J. 2025, 21, 704–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos Rodríguez, N.; Nieto Masot, A.; Cárdenas Alonso, G. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourism: A Clustering Approach for the Spanish Tourism Analysis. Land 2023, 12, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E.; Stasiak, J. Domestic Tourism Preferences of Polish Tourist Services’ Market in Light of Contemporary Socio-economic Challenges. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism; Kavoura, A., Borges-Tiago, T., Tiago, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Chapter 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amissah, E.F.; Addison-Akotoye, E.; Blankson-Stiles-Ocran, S. Service Quality, Tourist Satisfaction, and Destination Loyalty in Emerging Economies. In Marketing Tourist Destinations in Emerging Economies; Mensah, I., Balasubramanian, K., Jamaluddin, M., Alcoriza, G., Gaffar, V., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Kim, H.; Buning, R.J.; Harada, M. Adventure tourism motivation and destination loyalty: A comparison of decision and non-decision makers. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Jones, B. Enterprise Risk Management: From Theory to Practice. Risk Manag. Insur. Rev. 2021, 24, 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh, L.P.; Nguyen, T.T. Pandemic, social distancing, and social work education: Students’ satisfaction with online education in Vietnam. Soc. Work Educ. 2020, 39, 1074–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkic, J. Challenges in outdoor tourism explorations: An embodied approach. Tour. Geogr. 2021, 23, 228–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.; Sasidharan, V.; Álvarez, J.; Luis, A. Quality and sustainability of tourism development in Copper Canyon, Mexico: Perceptions of community stakeholders and visitors. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 27, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordova, F.; García, L.; Castaño, L.; Valverde, J. Gastronomy’s influence on choosing cultural tourism destinations: A study of Granada, Spain. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2024, 55, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, A.; Yüksel, F. The Expectancy–Disconfirmation Paradigm: A Critique. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2001, 25, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Berry, L.; Zeithaml, V. Refinement and reassessment of the servqual scale. J. Retail. 1991, 67, 420–450. [Google Scholar]

- Zubović, V. Adventure Tourism Experience–A Systematic Literature Review. In 8th International Thematic Monograph: Modern Management Tools and Economy of Tourism Sector in Present Era; SKRIPTA International: Belgrade, Belgium, 2023; pp. 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, G.; Tučková, Z.; Hoang, S. Psychological ownership and knowledge sharing: Key psychological drivers of sustainable tourist behavior. Acta Psychol. 2025, 253, 104715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache, M.; Bagarić, L.; Carvache, O.; Carvache, W. Segmentation by recreation experiences of demand in coastal and marine destinations: A study in Galapagos, Ecuador. PLoS ONE 2025, 2, e0316614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Mai, T. Does transformative tourism experience lead to loyalty among Vietnamese tourists? Anatolia 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Brien, A.; Primiana, I.; Wibisono, N. Tourist loyalty in creative tourism: The role of experience quality, value, satisfaction, and motivation. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2019, 23, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuquinga, J.E.; Castro, A.D.; Chiquito, M.M.; Tarabó, A.E. Planificación turística sostenible: Las comunidades de Santa Elena. Explor. Digit. 2019, 3, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Xiang, Y.; Weber, K.; Liu, Y. Motivation and involvement in adventure tourism activities: A Chinese tourists’ perspective. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 1066–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Park, D.B. Relationships among perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty: Community-based ecotourism in Korea. J. Travel Tour Mark. 2017, 34, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Hult, G.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; SAGE Publication, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354331182_A_Primer_on_Partial_Least_Squares_Structural_Equation_Modeling_PLS-SEM (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Pomfret, G. Mountaineering adventure tourists: A conceptual framework for research. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct and Indicators | λ | Proportional α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Assurance (HA) | 0.908 | 0.912 | 0.646 | |

| HA1: To visit a destination with facilities for social distancing | 0.720 | |||

| HA2: To be in a destination with security and protection | 0.846 | |||

| HA3: To be in a destination with transportation with better capacity | 0.750 | |||

| HA4: To be in a destination with health guarantees | 0.857 | |||

| HA5: To stay in accommodations and restaurants that are continuously disinfected | 0.841 | |||

| HA6: To be attended by service staff with safety equipment (mask, gloves) | 0.859 | |||

| HA7: To be in a destination with enough outdoor space | 0.740 | |||

| Intellectual Curiosity (IC) | 0.928 | 0.937 | 0.668 | |

| IC1: To learn about the things around me | 0.818 | |||

| IC2: To satisfy my curiosity | 0.788 | |||

| IC3: To explore new ideas | 0.844 | |||

| IC4: To learn about myself | 0.754 | |||

| IC5: To expand my knowledge | 0.856 | |||

| IC6: To discover new things | 0.832 | |||

| IC7: To be creative | 0.795 | |||

| IC8: To use my imagination | 0.844 | |||

| Social Connection (SC) | 0.895 | 0.901 | 0.613 | |

| SC1: To develop close friendships | 0.730 | |||

| SC2: To reveal my thoughts, feelings, or physical abilities to others | 0.788 | |||

| SC3: To be socially competent and skilled | 0.850 | |||

| SC4: To gain a sense of belonging | 0.811 | |||

| SC5: To earn the respect of others | 0.770 | |||

| SC6: To improve my social skills | 0.798 | |||

| SC7: To meet new friends | 0.726 | |||

| Physical Fitness (PF) | 0.911 | 0.915 | 0.736 | |

| PF1: To be active | 0.813 | |||

| PF2: To develop physical skills and abilities | 0.901 | |||

| PF3: To stay physically fit | 0.846 | |||

| PF4: To use my physical abilities | 0.873 | |||

| PF5: To develop physical fitness | 0.855 | |||

| Stress Relief (SR) | 0.885 | 0.888 | 0.686 | |

| SR1: To relax physically | 0.788 | |||

| SR2: To relax mentally | 0.851 | |||

| SR3: To avoid the hustle and bustle of daily activities | 0.804 | |||

| SR4: To rest | 0.842 | |||

| SR5: To relieve stress and tension | 0.855 | |||

| Destination Quality (DQ) | 0.891 | 0.895 | 0.650 | |

| DQ1: Reasonable price | 0.745 | |||

| DQ2: Safety and protection | 0.861 | |||

| DQ3: Good service | 0.866 | |||

| DQ4: Good facilities | 0.844 | |||

| DQ5: Reliable travel insurance | 0.768 | |||

| DQ6: Recommendation | 0.743 | |||

| Loyalty (LOY) | 0.871 | 0.872 | 0.796 | |

| LOY1: I intend to revisit a coastal destination | 0.870 | |||

| LOY2: I intend to recommend that my friends visit a coastal destination | 0.906 | |||

| LOY3: When I talk about coastal destinations after the visit, I will say positive things | 0.900 |

| Factor | HA | IC | SC | PF | SR | DQ | LOY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Assurance (HA) | 0.804 | 0.573 | 0.449 | 0.496 | 0.607 | 0.758 | 0.581 |

| Intellectual Curiosity (IC) | 0.531 | 0.817 | 0.749 | 0.734 | 0.616 | 0.612 | 0.555 |

| Social Connection (SC) | 0.406 | 0.683 | 0.783 | 0.756 | 0.461 | 0.424 | 0.407 |

| Physical Fitness (PF) | 0.454 | 0.677 | 0.689 | 0.858 | 0.670 | 0.568 | 0.569 |

| Stress Relief (SR) | 0.544 | 0.570 | 0.419 | 0.607 | 0.828 | 0.790 | 0.741 |

| Destination Quality (DQ) | 0.684 | 0.566 | 0.387 | 0.514 | 0.704 | 0.806 | 0.786 |

| Loyalty (LOY) | 0.515 | 0.509 | 0.369 | 0.512 | 0.653 | 0.694 | 0.892 |

| Hypotheses | (β) | T Statistics | p-Values | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1. Health Assurance → Destination Quality | 0.395 | 7.401 | 0.000 | Yes |

| H2. Intellectual Curiosity → Destination Quality | 0.143 | 2.589 | 0.010 | Yes |

| H3. Social Connection → Destination Quality | 0.067 | 1.530 | 0.126 | No |

| H4. Physical Fitness → Destination Quality | 0.031 | 0.616 | 0.538 | No |

| H5. Stress Relief → Destination Quality | 0.417 | 6.206 | 0.000 | Yes |

| H6. Destination Quality → Loyalty | 0.634 | 14.132 | 0.000 | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orden-Mejía, M.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Palomino, O.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Minchenkova, L.; Núñez-Naranjo, A.; Minchenkova, A.; Carvache-Franco, W. Motivations, Quality, and Loyalty: Keys to Sustainable Adventure Tourism in Natural Destinations. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5789. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135789

Orden-Mejía M, Carvache-Franco M, Palomino O, Carvache-Franco O, Minchenkova L, Núñez-Naranjo A, Minchenkova A, Carvache-Franco W. Motivations, Quality, and Loyalty: Keys to Sustainable Adventure Tourism in Natural Destinations. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):5789. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135789

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrden-Mejía, Miguel, Mauricio Carvache-Franco, Olenka Palomino, Orly Carvache-Franco, Lidia Minchenkova, Aracelly Núñez-Naranjo, Aleksandra Minchenkova, and Wilmer Carvache-Franco. 2025. "Motivations, Quality, and Loyalty: Keys to Sustainable Adventure Tourism in Natural Destinations" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 5789. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135789

APA StyleOrden-Mejía, M., Carvache-Franco, M., Palomino, O., Carvache-Franco, O., Minchenkova, L., Núñez-Naranjo, A., Minchenkova, A., & Carvache-Franco, W. (2025). Motivations, Quality, and Loyalty: Keys to Sustainable Adventure Tourism in Natural Destinations. Sustainability, 17(13), 5789. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135789