Sustainability at the Intersection: A Bibliometric Analysis of the Impact of Social Movements on Environmental Activism from 1998 to 2025

Abstract

1. Introduction

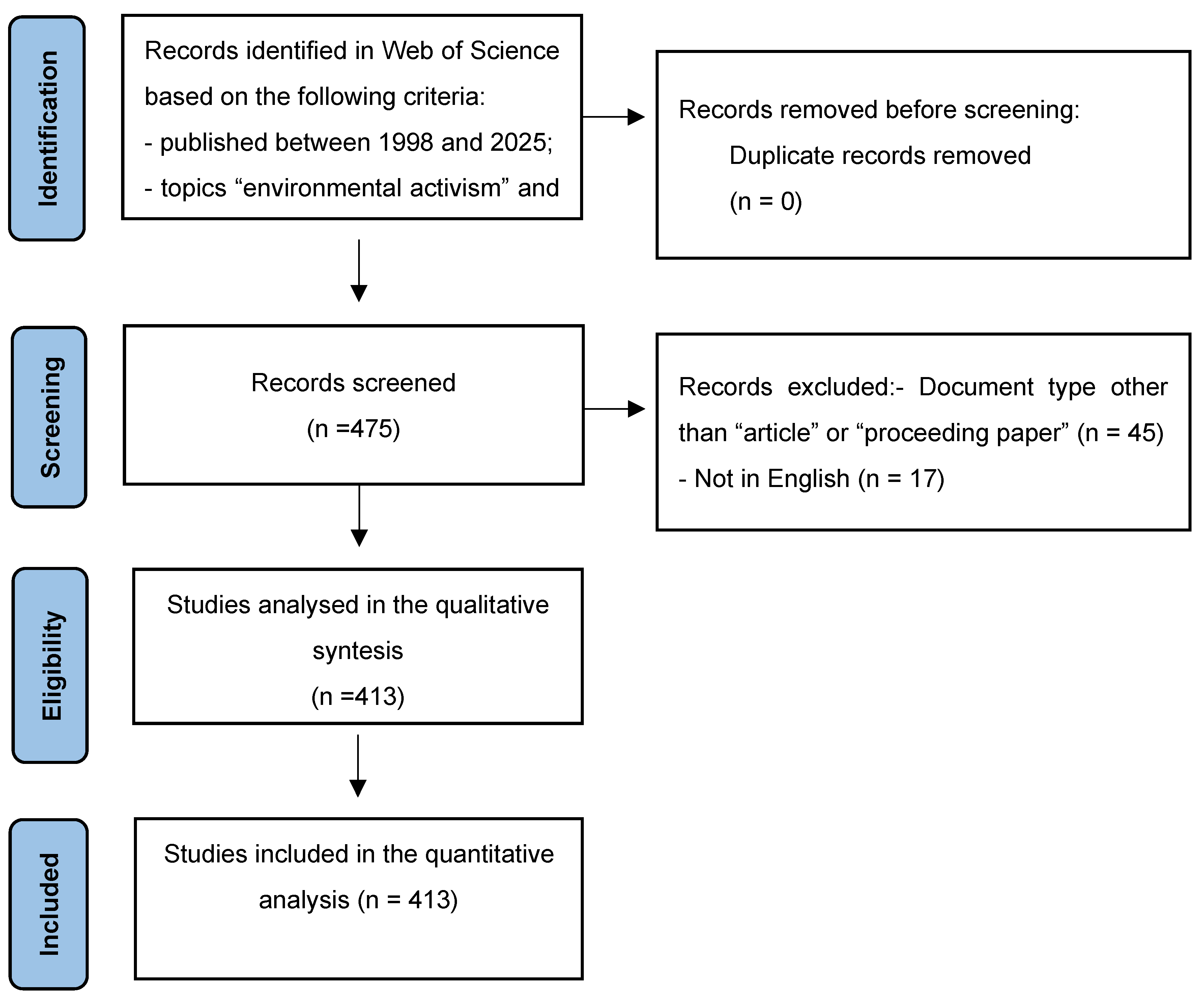

2. Materials and Methods

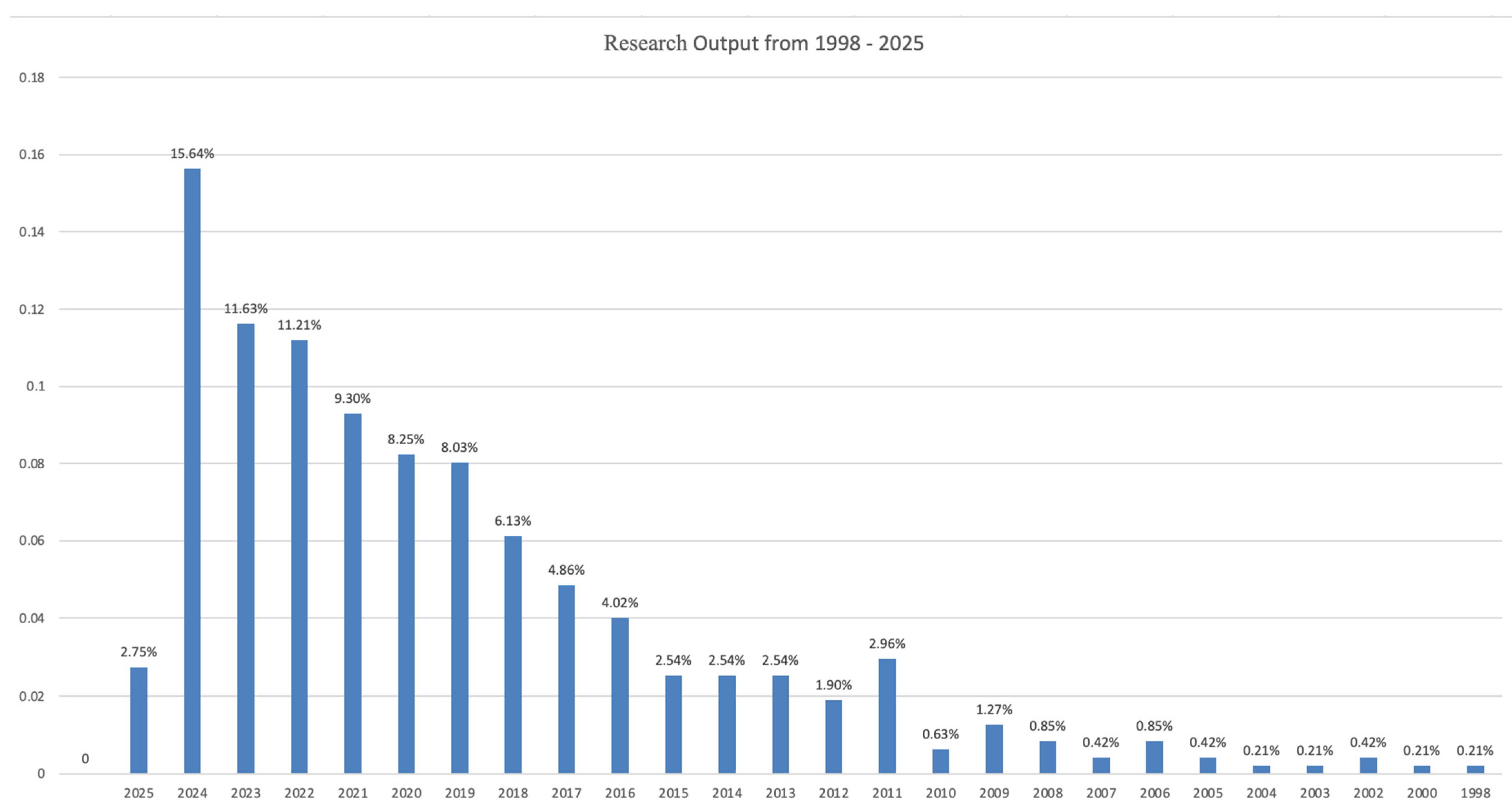

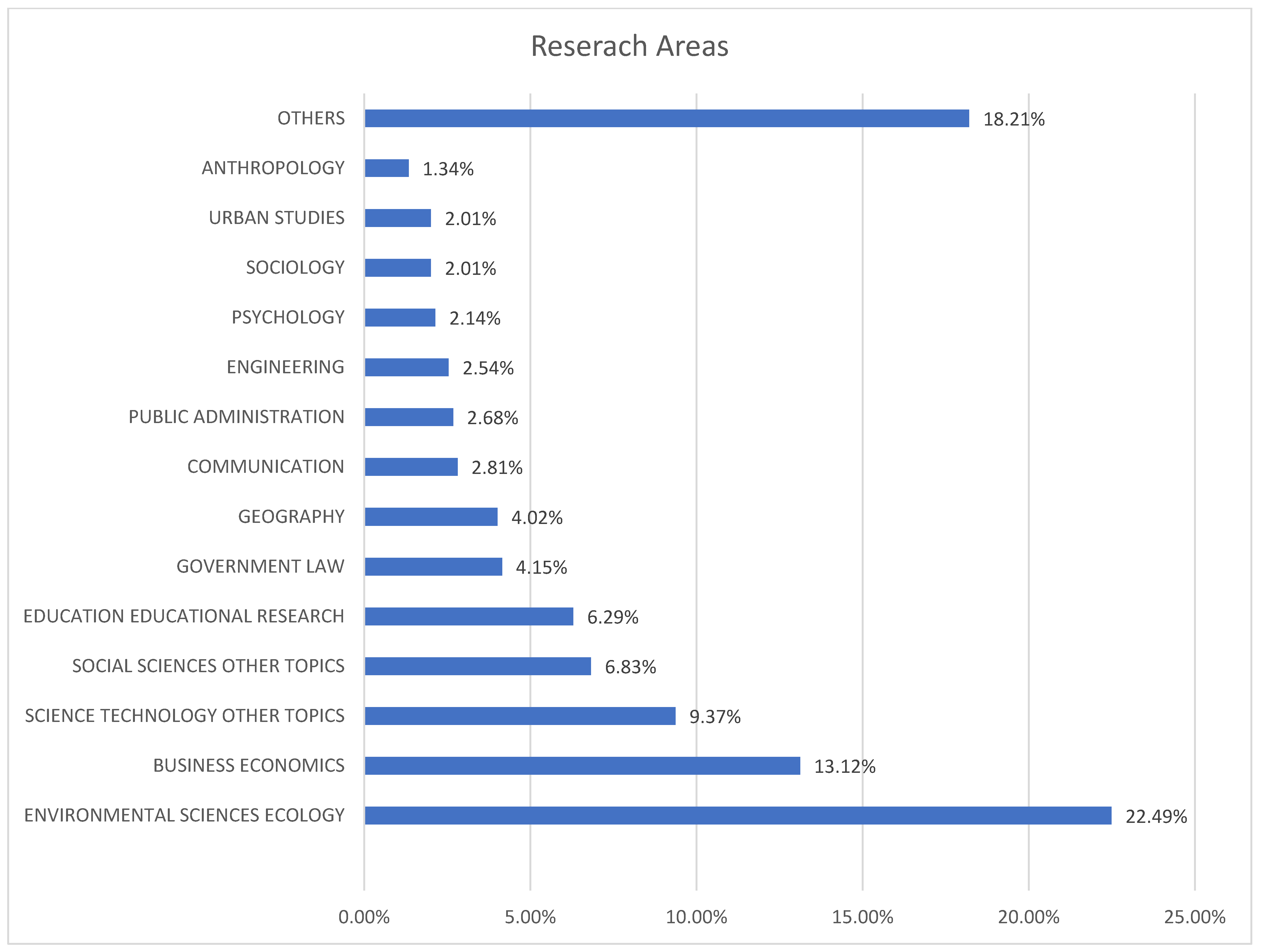

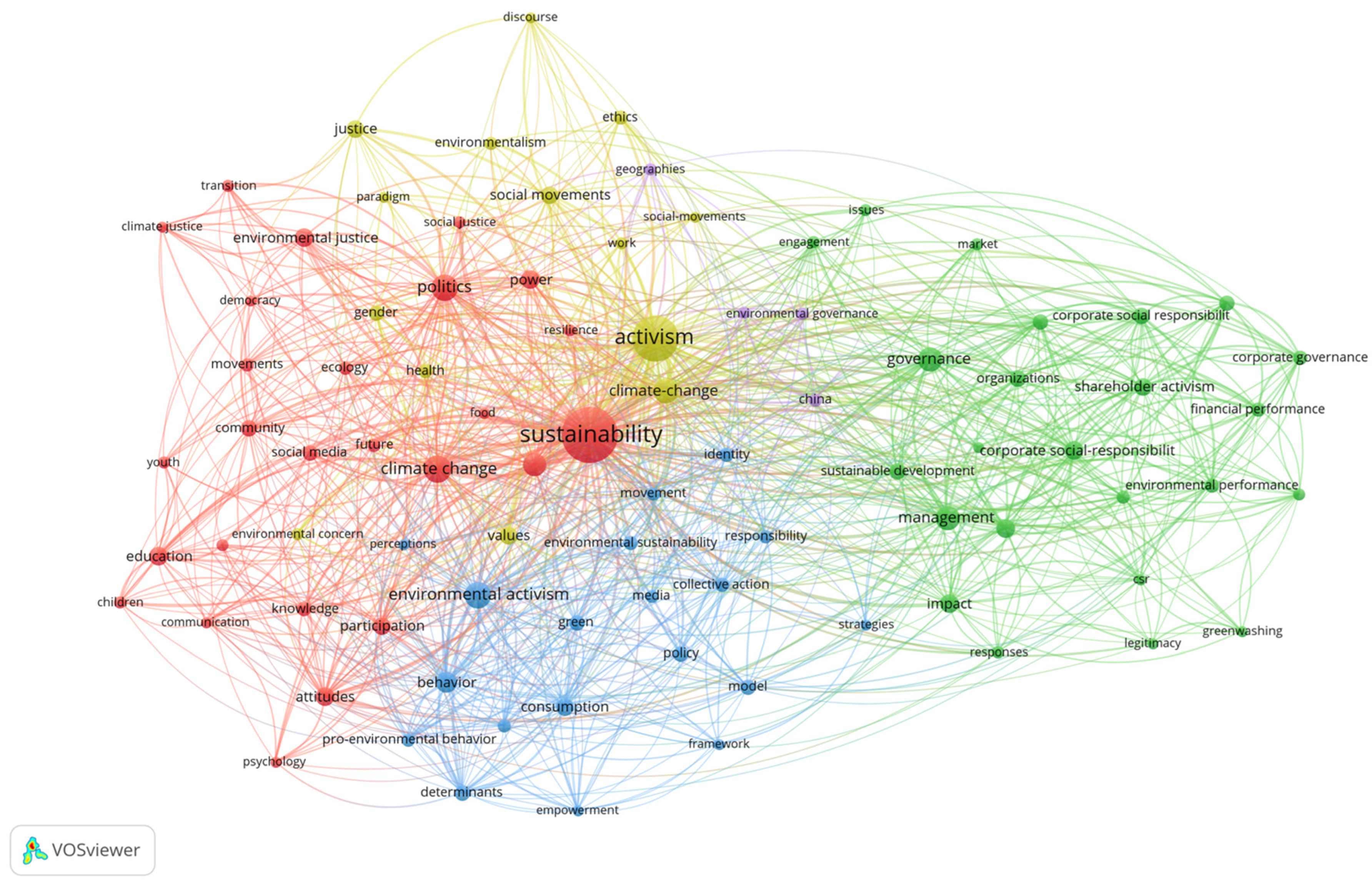

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martinez-Alier, J.; Anguelovski, I.; Bond, P.; Del Bene, D.; Demaria, F. Between Activism and Science: Grassroots Concepts for Sustainability Coined by Environmental Justice Organizations. J. Political Ecol. 2014, 21, 19–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temper, L.; Walter, M.; Rodriguez, I.; Kothari, A.; Turhan, E. A Perspective on Radical Transformations to Sustainability: Resistances, Movements and Alternatives. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passas, I. The Evolution of ESG: From CSR to ESG 2.0. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 1711–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, A.; John, J.; Thomas, A.S.; Smiju, I. Evolution of CSR and ESG Concepts in the Frame of Sustainability: Insights From Thematic Evolution Across Nations. In ESG Frameworks for Sustainable Business Practices; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Stoian, C.E.; Șimon, S.; Gherheș, V. A Comparative Analysis of the Use of the Concept of Sustainability in the Romanian Top Universities’ Strategic Plans. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGregor Pelikánová, R. Modern History of Sustainability. In Sustainability in Europe: Roots and Evolution of the Current Legal Regime; MacGregor Pelikánová, R., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 81–102. ISBN 978-3-031-74689-5. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tulder, R.; Van Mil, E. Principles of Sustainable Business: Frameworks for Corporate Action on the SDGs; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-003-09835-5. [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor Pelikánová, R. Terminology and Scientific Background of Sustainability. In Sustainability in Europe: Roots and Evolution of the Current Legal Regime; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, D. Enablers of a Circular Economy: A Strength-Based Stakeholder Engagement Approach. In Stakeholder Engagement in the Circular Economy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor, S. Finding Transformative Potential in the Cracks? The Ambiguities of Urban Environmental Activism in a Neoliberal City. Soc. Mov. Stud. J. Soc. Cult. Political Protest 2019, 20, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Favari, D.; Gastaldi, M.; Kirchherr, J. Towards Circular Economy Indicators: Evidence from the European Union. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, 42, 670–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujová, E. Comparative analysis of CSR reporting practices in Poland and Slovakia. Scientific Papers of Silesian University of Technology. Organ. Manag. Ser. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, M.R.; Porter, M. Creating Shared Value; FSG: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Palea, V.; Migliavacca, A.; Gordano, S. Scaling Up the Transition: The Role of Corporate Governance Mechanisms in Promoting Circular Economy Strategies. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 349, 119544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrad, C.; Gherheș, V. A Human Resources Perspective on Responsible Corporate Behavior. Case Study: The Multinational Companies in Western Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petera, P.; Wagner, J.; Pakšiová, R. The Influence of Environmental Strategy, Environmental Reporting and Environmental Management Control System on Environmental and Economic Performance. Energies 2021, 14, 4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onukwulu, E.C.; Dienagha, I.N.; Digitemie, W.N.; Egbumokei, P.I.; Oladipo, O.T. Enhancing Sustainability through Stakeholder Engagement: Strategies for Effective Circular Economy Practices. South Asian J. Soc. Stud. Econ. 2025, 22, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provensi, T.; Marcon, M.L.; Sehnem, S.; Campos, L.M.S.; de Queiroz, A.F.S.L. Exploring ESG and Circular Economy in Brazilian Companies: The Role of Stakeholder Engagement. Benchmarking Int. J. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernicova-Buca, M.; Dragomir, G.-M.; Gherheș, V.; Palea, A. Students’ Awareness Regarding Environment Protection in Campus Life: Evidence from Romania. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chewinski, M.; Corrigall–Brown, C. Channeling Advocacy? Assessing How Funding Source Shapes the Strategies of Environmental Organizations. Soc. Mov. Stud. 2020, 19, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, D.; Henn, M. COVID-Ized Ethnography: Challenges and Opportunities for Young Environmental Activists and Researchers. Societies 2021, 11, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoglund, A.; Böhm, S. Prefigurative Partaking: Employees’ Environmental Activism in an Energy Utility. Organ. Stud. 2020, 41, 1257–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildemeersch, D.; Læssøe, J.; Håkansson, M. Young Sustainability Activists as Public Educators: An Aesthetic Approach. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2022, 21, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F. I Trends in Environmental Activism. Int. Political Sci. Abstr. 2023, 73, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bektenova, M.; Akessina, A. Environmental Activism: Trends and Prospects. J. Cent. Asian Stud. 2021, 84, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, J. Environmental Activism; ABC-CLIO: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 1–352. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, P. Environmental Citizenship and Youth Activism. In Conceptualizing Environmental Citizenship for 21st Century Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Rabe, C. Environmental Justice Teaching in an Undergraduate Context: Examining the Intersection of Community-Engaged, Inclusive, and Anti-Racist Pedagogy. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2024, 14, 492–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolfi, H.E.; Rushton, E.A.; Silva, L.F.; da Silva Carvalho, M.B.S. Teacher Educators and Environmental Justice: Conversations about Education for Environmental Justice between Science and Geography Teacher Educators Based in England and Brazil. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2024, 19, 257–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loginova, L.V.; Scheblanova, V.V. The Phenomenon of Environmental Activism in the Perspective of Sociological Discourse. Logos Et Prax. 2021, 20, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.; Bingamon, L. Activism as Occupation: Promoting Health in Marginalized Communities. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 73, 7311505165p1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J. Slow Resistance: Feminist and Queer Activism in ‘Illiberal’Contexts. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 2024, 13675494241286987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonello, M. Sustainability in the boardroom. In The Conference Board Director Notes; The Conference Board: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hug, K.; Zhang, L.E. When and How to Engage with Employee Environmental Activism: Lessons Learned from a Global Service Firm. Eur. Manag. J. 2024, 42, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, J.; Serafeim, G.; Yoon, A. Shareholder Activism on Sustainability Issues. Available at SSRN 2805512 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J. Effective Activism–Sponsor Identity in Environmental and Social Proposal Filing. In Proceedings of the 30th Australasian Finance and Banking Conference, Sydney, Australia, 13–15 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, A.; Uysal, N.; Taylor, M. Unleashing the Power of Networks: Shareholder Activism, Sustainable Development and Corporate Environmental Policy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 712–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barko, T.; Cremers, M.; Renneboog, L. Shareholder Engagement on Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 180, 777–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Labajos, B. Artistic Activism Promotes Three Major Forms of Sustainability Transformation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 57, 101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, D.P.; Anderson, C.; Barry, J.; Castán Broto, V.; de Cheveigné, S.; Chilvers, J.; Crowther, A.; Hupé, J.-M.; Kalaugher, L.; Labussiere, O. Developing a Minifesta for Effective Academic-Activist Collaboration in the Context of the Climate Emergency. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1384614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliev, I.; Janssen, M.A.; Theesfeld, I.; Pritchard, C.; Pirscher, F.; Lee, A. Channeling Environmentalism into Climate Policy: An Experimental Study of Fridays for Future Participants from Germany. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 114035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidenbach, J.; Herrera, J. Learning in the Struggle: Reframing Economic & Environmental Justice. J. Sustain. Educ. 2013, 5, 101–122. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, K. Managing to Grow with Environmental Justice. Public Work. Manag. Policy 2001, 6, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Linnenluecke, M.; Smith, T. Shareholder Activism, Divestment, and Sustainability. Account. Financ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Alier, J.; Healy, H.; Temper, L.; Walter, M.; Rodriguez-Labajos, B.; Gerber, J.-F.; Conde, M. Between Science and Activism: Learning and Teaching Ecological Economics with Environmental Justice Organisations. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.; O’Donovan, G.; Willett, R. The Effect of Environmental Activism on the Long-Run Market Value of a Company: A Case Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, L.E.B.; Bandeira, E.L.; de Arruda, H.R.; Romero, C.B.A. Atitude Para o Consumo Colaborativo: Um Estudo Baseado Na Consciência Ambiental Attitude for Collaborative Consumption: A Study Based on Environmental Awareness. Rev. Gestão E Secr. (Manag. Adm. Prof. Rev.) 2020, 11, 24–49. [Google Scholar]

- Miguel, A.; Miranda, S. The Brand as an Example for Sustainability: The Impact of Brand Activism on Employee Pro-Environmental Attitudes. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, D.; Khan, T. Sustainability-Focused Accounting, Management, and Governance Research: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelaki, E.; Garefalakis, A.; Kourgiantakis, M.; Sitzimis, I.; Passas, I. ESG Integration and Green Computing: A 20-Year Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulou, A.; Angelaki, E.; Rompogiannakis, I.; Passas, I.; Garefalakis, A.; Thanasas, G. Digital Transformation in SMEs: Pre-and Post-COVID-19 Era: A Comparative Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.X.; Kjaerulf, F.; Turner, S.; Cohen, L.; Donnelly, P.D.; Muggah, R.; Davis, R.; Realini, A.; Kieselbach, B.; MacGregor, L.S. Transforming Our World: Implementing the 2030 Agenda through Sustainable Development Goal Indicators. J. Public Health Policy 2016, 37, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odobaša, R.; Marošević, K. Expected Contributions of the European Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) to the Sustainable Development of the European Union. EU Comp. Law Issues Chall. Ser. (ECLIC) 2023, 7, 593–612. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, R.S.; Lovell, S.T. Grassroots Engagement with Transition to Sustainability: Diversity and Modes of Participation in the International Permaculture Movement. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudler, K.; Dennis, L.; DiNella, M.; Ford, N.; Mendez, J.; Long, J. Intersectional Sustainability and Student Activism: A Framework for Achieving Social Sustainability on University Campuses. Educ. Citizsh. Soc. Justice 2021, 16, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, B.P.; Silva, J.I.A.O.; Gomes, I.R.F.D. Public Policy Environment: Legalization and Judicial Activism for Sustainable Development. Rev. Fac. Derecho 2017, 153–179. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, M.; De Rosa, A. Design for Social Sustainability. A Reflection on the Role of the Physical Realm in Facilitating Community Co-Design. Des. J. 2017, 20, S1705–S1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCally, M. Medical Activism and Environmental Health. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2002, 584, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomo, D.; Forno, F.; Simon, M. Grassroots (Economic) Activism in Times of Crisis: Mapping the Redundancy of Collective Actions. Partecip. E Conflitto 2015, 2015, 328–342. [Google Scholar]

- Morigi, J.; Krebs, L.M. Social Mobilization Networks: The Greenpeace Informational Practices. Inf. Soc.-Estud. 2012, 22, 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Checker, M. Wiped out by the “Greenwave”: Environmental Gentrification and the Paradoxical Politics of Urban Sustainability. City Soc. 2011, 23, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.A.I.; Alsenany, S.A.; Abdelaliem, S.M.F.; Asal, M.G.R. Exploring Organisational Agility’s Impact on Nurses’ Green Work Behaviour: The Mediating Role of Climate Activism. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockrey, S.; Brennan, L.; Verghese, K.; Staples, W.; Binney, W. Enabling Employees and Breaking down Barriers: Behavioural Infrastructure for pro-Environmental Behaviour. In Research Handbook on Employee Pro-Environmental Behaviour; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 313–346. ISBN 1-78643-283-8. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, B.P.; Brison, N.T.; Dietrich, A. Conceptualizing and Recognizing Eco-Activism within Sport. In Athletic Activism; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2023; Volume 17, pp. 85–103. ISBN 1-80262-204-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kowasch, M.; Cruz, J.P.; Reis, P.; Gericke, N.; Kicker, K. Climate Youth Activism Initiatives: Motivations and Aims, and the Potential to Integrate Climate Activism into ESD and Transformative Learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Hess, D.J.; Cantoni, R.; Lee, D.; Brisbois, M.C.; Walnum, H.J.; Dale, R.F.; Rygg, B.J.; Korsnes, M.; Goswami, A. Conflicted Transitions: Exploring the Actors, Tactics, and Outcomes of Social Opposition against Energy Infrastructure. Glob. Environ. Change 2022, 73, 102473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomnyuk, V.; Varavallo, G.; Parisi, T.; Barbera, F. All Shades of Green: The Anatomy of the Fridays for Future Movement in Italy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Uggento, A.M.; Piscitelli, A.; Ribecco, N.; Scepi, G. Perceived Climate Change Risk and Global Green Activism among Young People. Stat. Methods Appl. 2023, 32, 1167–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J. The Relationship between Sustainable Supply Chain Management, Stakeholder Pressure and Corporate Sustainability Performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 119, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, I.; Delgado-Ceballos, J. Defining and Measuring Corporate Sustainability: Are We There Yet? Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T.; Raschke, R.L. Stakeholder Legitimacy in Firm Greening and Financial Performance: What about Greenwashing Temptations? J. Bus. Res. 2023, 155, 113393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Lyon, T.P.; Maxwell, J.W. Understanding the Role of the Corporation in Sustainability Transitions. Organ. Environ. 2019, 32, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S.; Salomon, A.K.; Newell, D.; Waterfall, P.H.; Brown, K.; Harris, L.M.; Sumaila, U.R. Indigenous Women Respond to Fisheries Conflict and Catalyze Change in Governance on Canada’s Pacific Coast. Marit. Stud. 2018, 17, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, S.T.; Highby, W. Environmental Activism of Teacher-Scholars in the Neoliberal University. New Political Sci. 2018, 40, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denedo, M.; Thomson, I.; Yonekura, A. Ecological Damage, Human Rights and Oil: Local Advocacy NGOs Dialogic Action and Alternative Accounting Practices; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2019; Volume 43, pp. 85–112. [Google Scholar]

- McKimm, J.; McLean, M. Rethinking Health Professions’ Education Leadership: Developing ‘Eco-Ethical’Leaders for a More Sustainable World and Future. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.J.; Dupré, K.E.; McEvoy, A.; Kenny, S. Community Perceptions and Pro-Environmental Behavior: The Mediating Roles of Social Norms and Climate Change Risk. Can. J. Behav. Sci./Rev. Can. Des Sci. Du Comport. 2021, 53, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S. Factors Influencing Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors: A UK Case Study of Household Waste Management. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 435–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, W.; Hamilton, T. Just Green Enough: Contesting Environmental Gentrification in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Local Environ. 2012, 17, 1027–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehrsen, J. Muslims and Climate Change: How Islam, Muslim Organizations, and Religious Leaders Influence Climate Change Perceptions and Mitigation Activities. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2021, 12, e702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.K.; Garg, A.; Ram, S.; Gajpal, Y.; Zheng, C. Research Trends in Green Product for Environment: A Bibliometric Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, M.H.R.; AbdELhay, E.S.; AbdELhay, I.S.; Amin, S.M.; El-Monshed, A.H.; Abdelaliem, S.M.F.; Alabdullah, A.A.S.; Eweida, R.S. Effectiveness of a Web-Based Educational Program on Climate Change Awareness, Climate Activism, and pro-Environmental Behavior among Primary Health Care in Rural Areas: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, S.; Sabelfeld, S. Adaptive Framing of Sustainability in CEO Letters. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2023, 36, 161–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestergren, S.; Drury, J.; Chiriac, E.H. How Collective Action Produces Psychological Change and How That Change Endures over Time: A Case Study of an Environmental Campaign. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 57, 855–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anguelovski, I. Healthy Food Stores, Greenlining and Food Gentrification: Contesting New Forms of Privilege, Displacement and Locally Unwanted Land Uses in Racially Mixed Neighborhoods. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2015, 39, 1209–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza, V.; Paredes, M.R.; D’Souza, C. How Greenfluencers Boost Climate Action: Why Inspirational Green Leadership Matters. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2025, 49, e70050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, F.; Jeong, Y.; Putri, I.A.; Kim, S. Sociopsychological Aspects of Butterfly Souvenir Purchasing Behavior at Bantimurung Bulusaraung National Park in Indonesia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, C.H.; Yalamanchili, B.; Fera, J. # Climate Change on TikTok: A Content Analysis of Videos. J. Community Health 2022, 47, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hilder, C.; Collin, P. The Role of Youth-Led Activist Organisations for Contemporary Climate Activism: The Case of the Australian Youth Climate Coalition. J. Youth Stud. 2022, 25, 793–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhania, M.; Chadha, G. Impact of Debt on Sustainability Reporting: A Meta-Analysis of the Moderating Role of Country Characteristics. J. Account. Lit. 2024, 46, 671–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, J.; Fisher, A. Activism via Humus: The Composters Decode Decomponomics. Environ. Commun. 2008, 2, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slager, R.; Chuah, K.; Gond, J.-P.; Furnari, S.; Homanen, M. Tailor-to-Target: Configuring Collaborative Shareholder Engagements on Climate Change. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 7693–7718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, A.; Lins, K.V.; Roth, L.; Towner, M.; Wagner, H.F. Renewable Governance: Good for the Environment? J. Account. Res. 2023, 61, 279–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermann, F.; Steindl, T. Stock Market Reactions to a Sovereign Wealth Fund’s Broad-Based Public Sustainability Engagement: European Evidence. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2025, 231, 106915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. The Tensions of University–City Relations in the Knowledge Society. Educ. Urban Soc. 2019, 51, 120–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustam, A.; Wang, Y.; Zameer, H. Does Foreign Ownership Affect Corporate Sustainability Disclosure in Pakistan? A Sequential Mixed Methods Approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 31178–31197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daugaard, D.; Jia, J.; Li, Z. Implementing Corporate Sustainability Information in Socially Responsible Investing: A Systematic Review of Empirical Research. J. Account. Lit. 2024, 46, 238–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callery, P.J.; Kim, E. Set & Done? Trade-offs between Stakeholder Expectation and Attainment Pressures in Corporate Carbon Target Management. J. Manag. Stud. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencze, L.; Sperling, E.; Carter, L. Students’ Research-Informed Socio-Scientific Activism: Re/Visions for a Sustainable Future. Res. Sci. Educ. 2012, 42, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almers, E. Pathways to Action Competence for Sustainability—Six Themes. J. Environ. Educ. 2013, 44, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.L.; Zint, M.T. Toward Fostering Environmental Political Participation: Framing an Agenda for Environmental Education Research. Environ. Educ. Res. 2013, 19, 553–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, D.; Pe’er, S.; Yavetz, B. Environmental Literacy of Youth Movement Members–Is Environmentalism a Component of Their Social Activism? Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 486–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadaki, M.; Clapcott, J.; Holmes, R.; MacNeil, C.; Young, R. Transforming Freshwater Politics through Metaphors: Struggles over Ecosystem Health, Legal Personhood, and Invasive Species in Aotearoa New Zealand. People Nat. 2023, 5, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlin, B.; Penzenstadler, B.; Cook, A. Pumping Up the Citizen Muscle Bootcamp: Improving User Experience in Online Learning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 562–573. [Google Scholar]

- Ozola, A. The Role of Public Participation and Environmnetal Activism in Environmental Governance in Latvia. In Proceedings of the International Scientific and Practical Conference, Rezekne, Latvia, 20–22 June 2011; Volume 2, pp. 360–367. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, A. Design Activism in an Indonesian Village. Des. Issues 2019, 35, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.P.; Malafaia, C.; Silva, J.E.; Rovisco, M.; Menezes, I. Educating for Participatory Active Citizenship: An Example from the Ecological Activist Field. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haucke, F.V. Smartphone-Enabled Social Change: Evidence from the Fairphone Case? J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1719–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orea-Giner, A.; Fusté-Forné, F. The Way We Live, the Way We Travel: Generation Z and Sustainable Consumption in Food Tourism Experiences. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, S.J.; Thomas, S.; O’neill, K.; Brondgeest, C.; Thomas, J.; Beltran, J.; Hunt, T.; Yassi, A. Visual Storytelling, Intergenerational Environmental Justice and Indigenous Sovereignty: Exploring Images and Stories amid a Contested Oil Pipeline Project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, K.; McCauley, D.; Heffron, R.; Stephan, H.; Rehner, R. Energy Justice: A Conceptual Review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetting, C. The European Green Deal. ESDN Rep. Dec. 2020, 2, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six Transformations to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

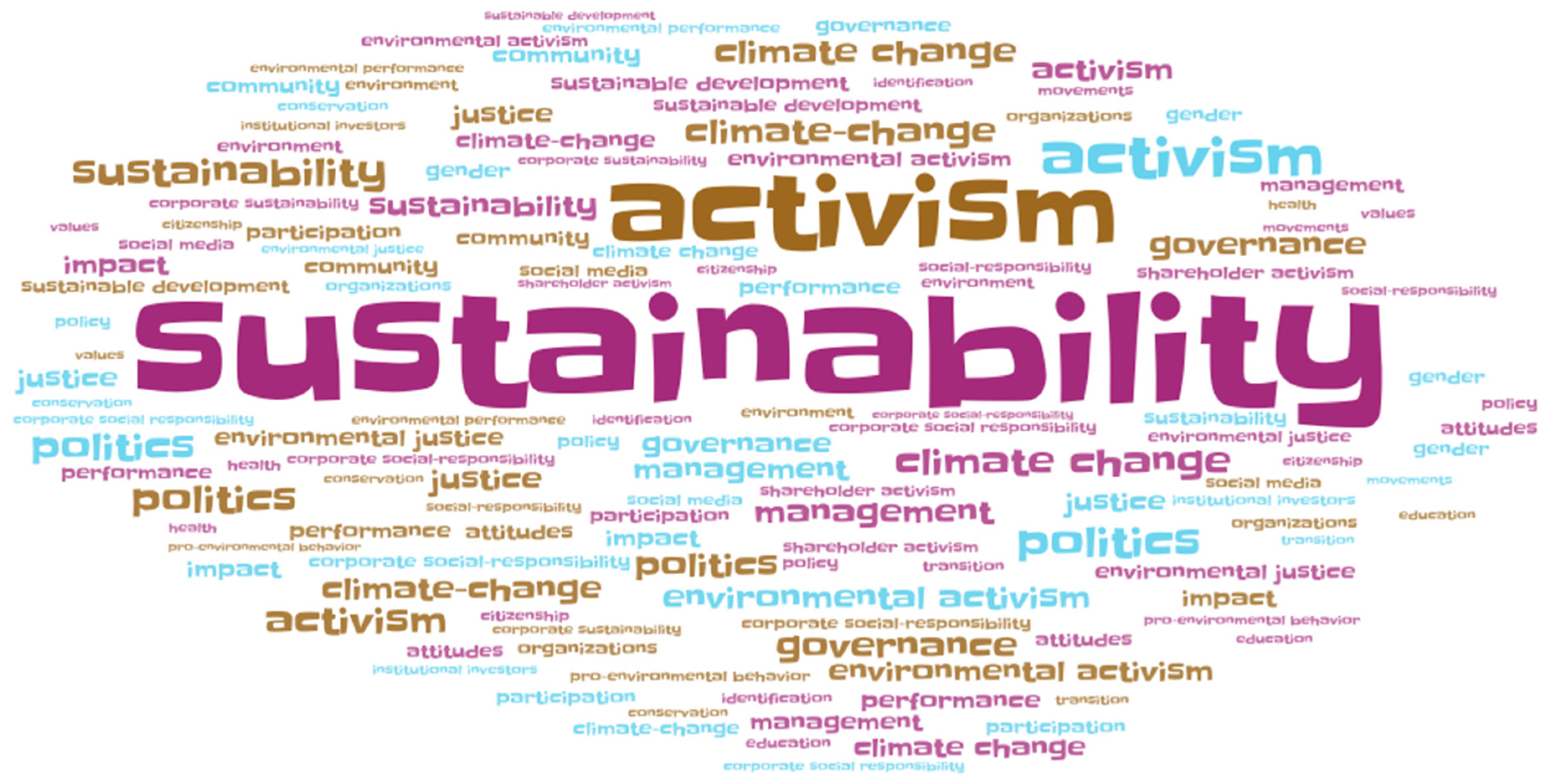

| Theme 1: social media and climate justice activism | Prominent terms: social, media, justice, movements, financial stability, change | Influential contributions: [54] Lovell, S. T.; [55] DiNella, M.; [37] Yang, C.-Y.; [56] Cunha, A.; [57] De Rosa, A.; [46] Case, R. A.; [58] McCally, M.; [59] Giacomo, S.; [60] Morigi, J.; [61] Checker, M.; [2] Temper, L.; [1] Martinez-Alier. |

| Theme 2: climate change, health, and educational policies | Prominent terms: climate change, health, education, policy, nurses, engagement, impacts | Influential contributions: [62] Abdelaliem, S. M. F.; [63] Lockrey, S.; Adams, A. E.; [64] Dietrich, A.; [65] Kowasch; [66] Hess, D. J.; [67] Tomnyuk, V.; [68] Piscitelli, A.; [69] Wolf, J.; [70] Montinel, I.; [71] Lee. |

| Theme 3: local leadership, non-violent activism, and gender equality | Prominent terms: leadership, non-violent, local, women, peace, power, change | Influential contributions: [72] Lyon, T. P.; [73] Waterfall, P. H.; [74] Romano, S. T.; [75] Yonekura, A.; [76] McLean, M. O.; [77] Smith, T.; [75] Thomson, I.; [78] Barr, S.; [79] Curran W.; [80]. |

| Theme 4: pro-environmental behavior and personal sustainability | Prominent terms: behavior, green, initiatives, eco, employee, pro, study | Influential contributions: [81] Zheng, C.; [62] Abdelaliem, S. M. F.; [82] Hashem, R. A.; [83] Sabelfeld, S.; [84] Drury, J.; [85] Anguelovski, I.; [86] Paredes, M. R.; [87] Ansari, F.; [80] Koehrsen, J.; [88] Basch C.; [89] Hilder C. |

| Theme 5: ESG, corporate performance, and sustainable investment | Prominent terms: corporate, ESG, firms, governance, investment, focus, disclosure, financial, funds | Influential contributions: [90] Singhania, M.; [91] Donoghue, J.; [92] Slager, R.; [93] Dyck, A.; [92] Homanen, M.; [94] Habermann, F.; [95] Liu, Y. S.; [96] Rustam, A.; [97] Daugaard, D.; [98] Callery, P. J.; [99] Bencze L.; [100] Almers E. [101]. |

| Theme 6: urban development, sustainable consumption, and community | Prominent terms: sustainable, food, development, consumption, urban, community, public | Influential contributions: [102] Pe’er, S.; Jenkins, K.; [103] MacNeil, C.; [104] Penzenstadler, B.; [105] Ozola, A.; [106] Crosby, A.; [107] Menezes, I.; [108] Haucke, F. V.; [109] Orea Ginear [110]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coman, C.; Gherhes, V.; Bucs, A.; Bucs, L.; Rad, D. Sustainability at the Intersection: A Bibliometric Analysis of the Impact of Social Movements on Environmental Activism from 1998 to 2025. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5741. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135741

Coman C, Gherhes V, Bucs A, Bucs L, Rad D. Sustainability at the Intersection: A Bibliometric Analysis of the Impact of Social Movements on Environmental Activism from 1998 to 2025. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):5741. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135741

Chicago/Turabian StyleComan, Claudiu, Vasile Gherhes, Anna Bucs, Lorant Bucs, and Dana Rad. 2025. "Sustainability at the Intersection: A Bibliometric Analysis of the Impact of Social Movements on Environmental Activism from 1998 to 2025" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 5741. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135741

APA StyleComan, C., Gherhes, V., Bucs, A., Bucs, L., & Rad, D. (2025). Sustainability at the Intersection: A Bibliometric Analysis of the Impact of Social Movements on Environmental Activism from 1998 to 2025. Sustainability, 17(13), 5741. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135741