Factors Associated with Psychological Flexibility in Higher Education Students: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

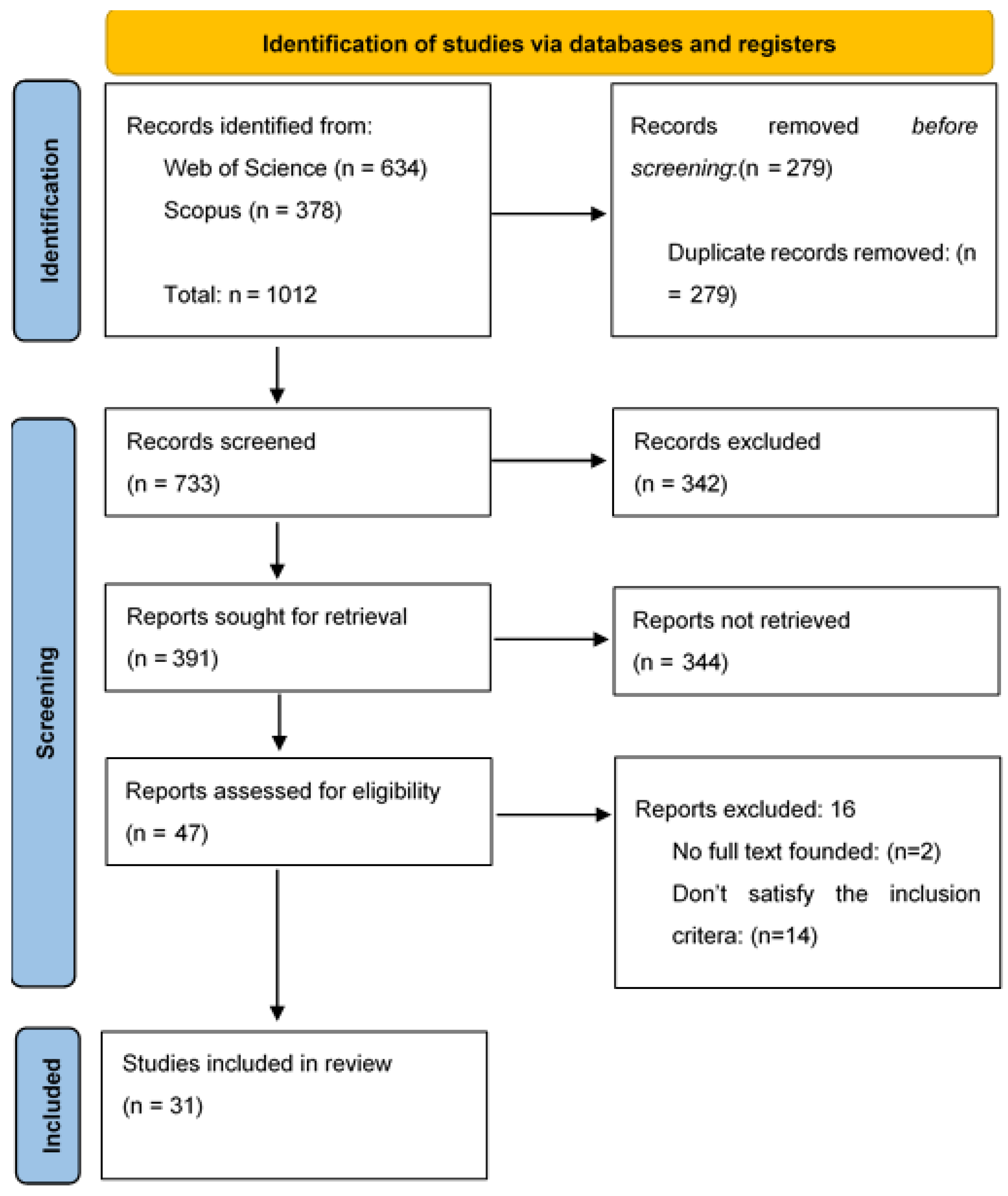

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Removal of Duplications

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

- Studies published between 2010 and 2023 were selected in both databases. The choice of this time frame reflects the limited number of studies on PF prior to 2010.

- Only documents labeled as “article” were selected in both databases. Only peer-reviewed articles published in indexed scientific journals were included in this study. Studies in different formats, such as conference proceedings, and grey literature, such as dissertations or preprints, were not included.

- Only those studies falling within the research areas of “psychology” and “education educational research” in the WoS database and “psychology” in the Scopus database were included. The Scopus database did not feature an “education” research area.

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Psychological Maladjustment

3.1.1. Anxiety Disorders and Depression

3.1.2. Stress, Distress, and Burnout

3.1.3. Disordered Eating

3.1.4. Conclusions: PF and Psychological Maladjustment

3.2. Psychological Well-Being

3.2.1. Values, Mindfulness and Meaning in Life

3.2.2. Well-Being, Self Compassion and Adaptive Potential

3.2.3. Conclusions: PF and Psychological Well-Being

3.3. Academic Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D.; Bunting, K.; Twohig, M.; Wilson, K.G. What is acceptance and commitment therapy? In A Practical Guide to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; Hayes, S.C., Strosahl, K.D., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.; Wilson, K.G.; Bissett, R.T.; Pistorello, J.; Toarmino, D.; Polusny, M.A.; Dykstra, T.A.; Batten, S.V.; Bergan, J.; et al. Measuring Experiential Avoidance: A Preliminary Test of a Working Model. Psychol. Rec. 2004, 54, 553–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Pistorello, J.; Levin, M.E. Acceptance and commitment therapy as a unified model of behavior change. Couns. Psychol. 2012, 40, 976–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chickering, A.W. Education and Identity; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Henton, J.; Lamke, L.; Murphy, C.; Haynes, L. Crisis reactions of college freshmen as a function of family support systems. Pers. Guid. J. 1980, 58, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherer, M. Depression and suicidal ideation in college students. Psychol. Rep. 1985, 57 (Suppl. 3), 1061–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldon, E.; Simmonds-Buckley, M.; Bone, C.; Mascarenhas, T.; Chan, N.; Wincott, M.; Barkham, M. Prevalence and risk factors for mental health problems in university undergraduate students: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 287, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, J.P.; Loring, R.K.; Noel, L.; Levitz, R.; Saluri, D. Increasing Student Retention: Effective Programs and Practices for Reducing the Dropout Rate; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1985; pp. 138–161. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, G.X.; Soh, X.C.; Hartanto, A.; Goh, A.Y.; Majeed, N.M. Prevalence of anxiety in college and university students: An umbrella review. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2023, 14, 100658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsley, J.D.; Pennington, A.; Corcoran, R. Supporting Mental Health and Wellbeing of University and College Students: A Systematic Review of Review-Level Evidence of Interventions. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewick, B.; Koutsopoulou, G.; Miles, J.; Slaa, E.; Barkham, M. Changes in Undergraduate Students’ Psychological Well-being as They Progress through University. Stud. High. Educ. 2010, 35, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, B.; Wilding, J.M. The Relation of Depression and Anxiety to Life-Stress and Achievement in Students. Br. J. Psychol. 2004, 95 Pt 4, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, S.K.; Lattie, E.G.; Eisenberg, D. Increased rates of mental health service utilization by US college students: 10-year population-level trends (2007–2017). Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.S.L. Student Mental Health: Some Answers and More Questions. J. Ment. Health 2018, 27, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amato, P. Coronavirus Accelerates Higher Education’s Trend Toward Distance Learning. Hechinger Report. 2020. Available online: https://hechingerreport.org/coronavirus-accelerates-higher-educations-trend-toward-distance-learning/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Hachey, A.C.; Wladis, C.W.; Conway, K.M. Is the Second Time the Charm? Investigating Trends in Online Re-Enrollment, Retention and Success. J. Educ. Online 2012, 9, n1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, E.-J.; Brockman, R.N. The Relationships between Psychological Flexibility, Self-Compassion, and Emotional Well-Being. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2016, 30, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, D.; Li, X. Psychological Flexibility Profiles, College Adjustment, and Subjective Well-Being among College Students in China: A Latent Profile Analysis. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2021, 20, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Systematic Reviews of Etiology and Risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., Jordan, Z., Eds.; JBI, 2024; Available online: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Asikainen, H. Examining indicators for effective studying: The interplay between student integration, psychological flexibility and self-regulation in learning. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 2018, 10, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asikainen, H.; Katajavuori, N. Exhausting and difficult or easy the association between psychological flexibility and study related burnout and experiences of studying during the pandemic. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1215549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asikainen, H.; Hailikari, T.; Mattsson, M. The Interplay between Academic Emotions, Psychological Flexibility and Self-Regulation as Predictors of Academic Achievement. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2018, 42, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, Y.; Aydin, G. Mindfulness and psychological flexibility: The mediating role of values. Hacet. Univ. J. Educ. 2021, 36, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berryhill, M.B.; Hayes, A.; Lloyd, K. Chaotic-Enmeshment and Anxiety: The Mediating Role of Psychological Flexibility and Self-Compassion. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2018, 40, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykin, D.M.; Anyanwu, J.; Calvin, K.; Orcutt, H.K. The Moderating Effect of Psychological Flexibility on Event Centrality in Determining Trauma Outcomes. Psychol. Trauma 2020, 12, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, M.E.; Lloyd-Richardson, E.E.; Satterfield, S.L.; Trisal, A.V. A Pilot Study of Experiencing Racial Microaggressions, Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms, and the Role of Psychological Flexibility. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2023, 51, 396–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butaney, B.; Hoover, E.B.; Coplan, B.; Bernard, K. Impact of COVID-19 on Student Perceived Stress, Life Satisfaction, and Psychological Flexibility: Examination of Gender Differences. J Am. Coll. Health 2023, 73, 1362–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Huang, P.; Yang, Q.; Ye, B. Perceived Stress, Psychological Flexibility Profiles, and Mental Health during COVID-19: A Latent Profile Analysis. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 1861–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein-Fox, L.; Pavlacic, J.M.; Buchanan, E.M.; Schulenberg, S.E.; Park, C.L. Valued Living in Daily Experience: Relations with Mindfulness, Meaning, Psychological Flexibility, and Stressors. Cognit. Ther. Res. 2020, 44, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorinelli, S.; Gallego, A.; Lappalainen, P.; Lappalainen, R. Psychological Processes in the Social Interaction and Communication Anxiety of University Students: The Role of Self-Compassion and Psychological Flexibility. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2022, 22, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hailikari, T.; Katajavuori, N.; Asikainen, H. Understanding Procrastination: A Case of a Study Skills Course. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 24, 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailikari, T.; Nieminen, J.; Asikainen, H. The Ability of Psychological Flexibility to Predict Study Success and Its Relations to Cognitive Attributional Strategies and Academic Emotions. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 42, 626–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffords, J.R.; Bayly, B.L.; Bumpus, M.F.; Hill, L.G. Investigating the Relationship between University Students’ Psychological Flexibility and College Self-Efficacy. J. Coll. Stud. Ret. 2020, 22, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keutler, M.; McHugh, L. Self-Compassion Buffers the Effects of Perfectionistic Self-Presentation on Social Media on Wellbeing. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2022, 23, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenborg, K.A.; Garnefski, N.; Kraaij, V.; Ly, V. Academic Stress, Mindfulness-Related Skills and Mental Health in International University Students. J Am. Coll. Health 2024, 72, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikova, T.I.; Filippova, S.A. Adaptive Potential of Students of Different Age Groups During a Pandemic. Russ. Psychol. J. 2022, 19, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, A.; Latzman, R.D. Psychological Flexibility and Self-Concealment as Predictors of Disordered Eating Symptoms. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2012, 1, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, A.; Price, M.; Anderson, P.L.; Wendell, J.W. Disordered Eating-Related Cognition and Psychological Flexibility as Predictors of Psychological Health among College Students. Behav. Modif. 2010, 34, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, A.; Boone, M.S.; Timko, C.A. The Role of Psychological Flexibility in the Relationship between Self-Concealment and Disordered Eating Symptoms. Eat. Behav. 2011, 12, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, A.; Price, M.; Latzman, R.D. Mindfulness Moderates the Relationship between Disordered Eating Cognitions and Disordered Eating Behaviors in a Non-Clinical College Sample. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2012, 34, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, A.; Le, J.; Cohen, L.L. The Role of Disordered-Eating Cognitions and Psychological Flexibility on Distress in Asian American and European American College Females in the United States. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 2014, 36, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajeri, M.; Alfooneh, A.; Imani, M. Studying the Mediating Role of Psychological Flexibility and Self-Compassion in the Relationship between Traumatic Memories of Shame and Severity of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms. Int. J. Body Mind Cult. 2023, 10, 2345–5802. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, C.W.; Lee, E.B.; Petersen, J.M.; Levin, M.E.; Twohig, M.P. Is Perfectionism Always Unhealthy? Examining the Moderating Effects of Psychological Flexibility and Self-Compassion. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 2576–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, W.; Zhou, Z.; Miao, M. Quadripartite Existential Meaning among Chinese: Internal Conceptual Structure and Reciprocating Relationship with Psychological Flexibility and Inflexibility. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2023, 202, 111961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, P.; O’dea, B.; Sheehan, J.; Tebbutt, J. Days out of Role in University Students: The Association of Demographics, Binge Drinking, and Psychological Risk Factors: Days out of Role among University Students. Aust. J. Psychol. 2015, 67, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoz, E.K.; Butcher, G.; Protti, T.A. A Preliminary Examination of Willingness and Importance as Moderators of the Relationship between Statistics Anxiety and Performance. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2017, 6, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fang, S.; Yang, C.; Tang, X.; Zhu, L.; Nie, Y. The Relationship between Psychological Flexibility and Depression, Anxiety and Stress: A Latent Profile Analysis. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, B.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q. Psychological Flexibility and COVID-19 Burnout in Chinese College Students: A Moderated Mediation Model. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2022, 24, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors and Year of Publication | Participants | Methodology and Variables | Aim of the Study | Results | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [21] | 117 | Methodology: Exploratory factor analysis Variables: student integration PF self-regulation in learning | To investigate the relationship between self-regulated learning, PF, and student integration. | PF is associated with advancing in studies, engaging in self-regulated learning, and integrating into the student community. | Moderate |

| [22] | 296 | Methodology: correlation and regression analyses, qualitative inductive content analysis Variables: PF study related burnout experiences of online studying | To examine the relationship between PF and burnout in relation to academic research. Additionally, to explore potential changes in burnout experiences and online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic among students with different levels of PF. | PF demonstrated an inverse correlation with study-related burnout. | Moderate |

| [23] | 274 | Methodology: Exploratory factor analysis and correlations Variables: academic emotions PF self-regulation study success | To investigate the associations among self-regulated learning, academic emotions, PF, study success, and study pace in the context of university-level studies. | PF emerged as a crucial mediator in the relationship between academic emotions and study pace. | Moderate |

| [24] | 432 | Methodology: structural equation modeling Variables: Mindfulness PF Values | To examine the predictive relationship between mindfulness and PF and, simultaneously, assess whether values act as a mediating factor in this association. | The findings revealed that the connection between mindfulness and PF was entirely mediated by values. | Moderate |

| [25] | 500 | Methodology: Multiple-sample latent structural equation modeling Variables: chaotic-enmeshment family functioning anxiety PF self-compassion | To investigate whether PF and self-compassion mediate the relationship between chaotically coupled family functioning and anxiety in a sample of 500 college students. | Elevated levels of chaotically-enmeshed family functioning were significantly linked to reduced levels of PF and self-compassion. Furthermore, the relationship between chaotic-enmeshment and anxiety was mediated by PF and self-compassion. | Moderate |

| [18] | 644 | Methodology: Latent profile analysis, Variables: PF college adjustment subjective well-being | To use latent profile analysis to examine subgroups of PF profiles in college students, focusing on key subcomponents of PF and examining relationships between these subgroups and college adjustment as well as subjective well-being. | Individuals characterized by high PF demonstrated superior adjustment to college life and experienced the highest levels of well-being. Conversely, those with low PF encountered greater challenges in adjusting to college life and reported lower well-being. Additionally, students from rural areas and those with siblings were associated with low PF. | Moderate |

| [26] | 125 | Methodology: Moderation analyses Variables: event centrality PF trauma recovery | To examine the effect of changes in PF, which relates to the ability to persist in behavior despite calls to do otherwise, on posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTS) and posttraumatic growth (PTG) as perceived by increasing event centrality | Reduced PF was linked to increased severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms as event centrality heightened. While both event centrality and PF individually predicted perceived posttraumatic growth, no interaction effect was observed. | Moderate |

| [27] | Methodology: correlation and regression analysis Variables: racial microaggressions obsessive-compulsive symptoms PF | To examine whether occurrence of microaggressions and PF contribute to understanding obsessive-compulsive disorder OCD symptoms in a university-based sample including undergraduate, graduate, and law students, while accounting for depression and anxiety. | There was a correlation observed between obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) symptoms, encounters with microaggressions, and PF. | Low | |

| [28] | 1239 | Methodology: multi year survey study, Variables: Perceived stress Life satisfaction PF | To identify coping strategies for stress and assess the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the well-being of both male and female physician assistant (PA) students. | Before the pandemic, male and female students had comparable levels of perceived stress and PF, with females reporting higher life satisfaction. However, after the pandemic, female students exhibited increased perceived stress and decreased PF. | Low |

| [29] | 659 | Methodology: cross-sectional survey, Latent profile analysis (LPA) Variables: Perceived Stress PF Profiles Mental Health | To use a person-centered approach to identify distinct subgroups of university students based on the Individualized Psychological Flexibility Index (PPFI), and simultaneously examining these subgroups’ risk factors (perceived stress) and various mental health outcomes, including depression, anxiety, negative affect, and positive affect to examine how it relates to outcomes. | Three profiles of PF were identified, and these profiles were found to be associated with perceived stress and mental health outcomes. | Moderate |

| [30] | 122 | Methodology: Survey study, multilevel modeling Variables: Mindfullness Meaning in life PF Daily stress Daily valued action | To examine how daily stress and intrapersonal resources, including mindfulness, meaning, and PF, influence valued functioning in a sample of 122 undergraduates. | Multilevel modeling results indicated notable variability in daily valued action, influenced by daily stress fluctuations and overall stress levels, along with dispositional mindfulness, meaning, and PF. | Moderate |

| [31] | 76 | Methodology: A survey as a part of an intervention study. Correlation and regression analyses Variables: social interaction and communication anxiety self-compassion PF | To examine the effects of self-compassion and PF in university students experiencing high levels of social interaction and communication anxiety. | Elevated social interaction and communication anxiety were correlated with reduced levels of self-compassion and PF. | Moderate |

| [32] | 135 | Methodology: Correlation and linear regression analyses Variables: time and effort management skills PF self-efficacy procrastination | To integrate diverse perspectives on procrastination by examining the interrelationship of students’ time and effort management skills, PF, and academic self-efficacy. | PF plays a significant individual role in elucidating procrastination, along with time and effort management skills. The close relationship between time and effort management and PF suggests that both factors should be considered when seeking to mitigate procrastination. | Moderate |

| [33] | 247 | Methodology: Correlation and SEM (Structural Equation Modeling) analyses Variables: PF study success cognitive attributional strategies academic emotions | To investigate the connections among students’ PF, cognitive-attributional strategies, academic emotions, and their impact on study success. | The interrelation among PF, cognitive-attributional strategies, and academic emotions is significant. PF showed positive associations with success expectations and positive emotions, while displaying negative correlations with task avoidance and negative emotions. | Moderate |

| [34] | 348 | Methodology: Correlation and hierarchial regression analyses Variables: PF Psychological inflexibility college self-efficacy | To comprehend the influence of PF and inflexibility on self-efficacy and explore the potential moderating effects of both year in college and underrepresented racial minority (URM) status. | Students exhibiting PF reported higher levels of college self-efficacy, while those displaying psychological inflexibility reported lower levels of college self-efficacy. | Low |

| [35] | Methodology: multiple mediation model, multivariate regression analysis Variables: PF Self-compassion perfectionistic self-presentation Subjective wellbeing. | To examine the relationship between perfectionistic social media self-presentation, self-compassion, PF, and perfectionism as measured by general well-being. | PF did not emerge as a significant mediating factor in the relationship between perfectionistic self-presentation on social media and overall wellbeing. | Low | |

| [36] | 190 | Methodology: Correlation and multiple regression analyses Variables: perceived academic stress mindfulness related constructs (i.e., mindfulness, self-compassion and PF) Anxiety symptoms depressive symptoms | To examine the relationships between academic stress, mindfulness-related constructs, and symptoms of anxiety and depression. | Higher levels of perceived academic stress were significantly associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms, while also correlating with lower levels of acting with mindfulness, reduced self-compassion, and diminished PF. However, none of the mindfulness-related constructs were identified as moderators in the relationship between perceived academic stress and anxiety or depressive symptoms. | Low |

| [37] | Methodology: Correlation analysis Variables: Adaptive potential Hardiness PF | To examine the relationships between PF and various expressions of coping mechanisms that serve as predictors of adjustment. | The composition of adaptive potential consists of elevated levels of hardiness and manifestations of psychological (cognitive and behavioral) flexibility. | Moderate | |

| [17] | 144 | Methodology: correlation and multiple regression analyses Variables: PF Self-Compassion Emotional Well-Being | To explore the relationship between PF, self-compassion, and emotional well-being. | Self-compassion showed significant correlations with PF processes, such as mindful acceptance, defusion, and emotional well-being. Moreover, self-compassion was found to predict unique variance in emotional well-being beyond that explained by PF across various indices. | Moderate |

| [38] | 833 | Methodology: cross sectional study, correlation and hierarchical multiple regression analyses Variables: PF Self-concealment Disordered eating | To examine differential associations of self-concealment and PF with various aspects of disordered eating (DE), including dieting, bulimia/binge eating, and oral control, as well as potential gender differences in these associations. | After adjusting for age, ethnicity, and BMI, dieting was found to have unique associations with both self-concealment and PF. When considering these demographic variables, PF, but not self-concealment, demonstrated a unique association with bulimia/food preoccupation. Additionally, neither self-concealment nor PF exhibited a unique association with oral control. | Low |

| [39] | Methodology: Correlation and hierarchical regression analyses Variables: Disordered eating-related cognition PF General psychological health Personal distress | To the cross-sectional study examine the relationship between eating-related cognition, PF, and adverse psychological outcomes within a nonclinical college sample. | The study found that disordered eating-related cognition exhibited a negative association with PF, and this, in turn, was linked to lower levels of psychological well-being and increased emotional distress in interpersonal situations. | Moderate | |

| [40] | 209 | Methodology: cross-sectional study, correlation, regression, and mediation analyses Variables: PF self-concealment disordered eating symptoms | To examine whether PF mediates the relationship between self-concealment and disordered eating (DE) symptoms in nonclinical college students. | Self-concealment showed a positive association with disordered eating (DE) symptoms, encompassing general eating disorder symptoms and related cognitions, while also exhibiting a negative correlation with PF. The study revealed an inverse relationship between PF and DE symptoms. Moreover, PF was identified as a mediator in the connection between self-concealment and DE symptoms, even after adjusting for gender, ethnicity, and body mass index (BMI). | Low |

| [41] | 278 | Methodology: cross sectional study, hierarchical multiple regressions Variables: PF Mindfulness Disordered eating Cognitions Disordered Eating Behaviors Psychological distress | To examine whether PF and mindfulness each independently influence the relationship between disordered eating cognitions and psychological distress, as well as the relationship between disordered eating cognitions and disordered eating behaviors. | Disordered eating cognitions, mindfulness, and PF demonstrated associations with psychological distress, even when accounting for factors such as gender, ethnicity, and body mass index. | Low |

| [42] | 87 + 231 | Methodology: survey study, correlation and multiple regression analyses Variables: PF Disordered-Eating Cognitions Psychological distress | To examine potential associations between eating disorder-related cognitive and PF among Asian-American and European-American female college students in the United States. | In both cohorts, there were positive associations between all categories of disordered-eating cognitions and psychological distress, and these were inversely linked to PF. Within the Asian American group, PF demonstrated a unique connection to psychological distress, even when considering other disordered-eating cognitions, age, and Body Mass Index (BMI). Meanwhile, in the European American group, PF maintained a unique association with psychological distress after accounting for other study variables. | Low |

| [43] | Methodology: structural equation modeling Variables: PF Self compassion Depression Anxiety Traumatic memories of shame | To further explore the mediating role of PF and self-compassion in the relationship between traumatic shame memories and depression and anxiety-related symptom severity. | The findings indicated that recollections of shame-inducing traumas had a notably positive effect on anxiety and depression, while having a notably negative impact on self-compassion and PF. Moreover, PF was observed to significantly reduce feelings of sadness and anxiety. | ||

| [44] | 677 | Methodology: Latent profile analysis, linear regression analysis Variables: PF self-compassion perfectionism wellbeing | To examine whether psychological skills such as PF and self-compassion play a moderating role in the relationship between perfectionism and general well-being. | PF and/or self-compassion buffered the negative effects of average and high perfectionism on quality of life and symptom impairment. | Moderate |

| [45] | 393 + 447 | Methodology: network analysis, cross-lagged longitudinal analysis Variables: Meaning in life PF Psychological inflexibility | To analyze the internal structure of the components within Meaning in Life (MIL) and examine their relationships with both PF and psychological inflexibility (PI). At the same time, it is known that both PF and Psychological inflexibility independently affect well-being. | PF (PF) exhibited a positive association with all Meaning in Life (MIL) components, while psychological inflexibility (PI) showed a negative association with them. Specifically, the MIL component of purpose significantly predicted both PF and PI in reverse. The relationship between PF/PI and purpose was found to be reciprocal. | Moderate |

| [46] | 3950 | Methodology: correlation and logistic regression analyses Variables: binge drinking psychological distress PF self-reported Days Out of Role (DOR) | To examine the relationship between demographic factors, binge drinking, psychological distress, PF, and self-reported Days of Role (DOR) among college university students, and further, to examine whether PF plays a moderating role in the relationship between psychological distress and DOR. | Experiencing more Days Out of Role (DOR) was linked to heightened psychological distress and decreased PF. Furthermore, the study identified that PF played a moderating role in the relationship between psychological distress and DOR. | Low |

| [47] | Methodology: Correlation and multiple regression analyses Variables: statistics-related PF statistics anxiety statistics performance | To examine the relationship between statistics anxiety, PF, and performance in statistics. | This research provides initial support for the idea that PF related to statistics (i.e., the willingness to engage with statistics materials and the perceived importance of statistics engagement) moderates the association between statistics anxiety and performance in statistics. | Moderate | |

| [48] | 1769 | Methodology: Latent profile analysis Variables: PF depression anxiety stress | To explore the potential classification of PF (PF) in Chinese college students, assess the existence of group variations in PF, and examine differences in latent PF profiles related to negative emotions such as depression, anxiety, and stress. | The levels of depression, anxiety, and stress exhibit significant variations across the three PF groups. | Low |

| [49] | 2377 | Methodology:Correlation and mediation analyses Variables: PF Perceived COVID-19 stress Perceived COVID-19 burnout Social support | To examine a moderated mediation model considering perceived COVID-19 stress and social support as mediators. | After accounting for gender, age, family location, and year of study, there was a significant association between PF and COVID-19 burnout, and this relationship was mediated by perceived COVID-19 stress. Additionally, social support mitigated the negative impact of perceived COVID-19 stress on PF and moderated the association between perceived COVID-19 stress and burnout. | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mursalzade, G.; Escriche-Martínez, S.; Valdivia-Salas, S.; Jiménez, T.I.; López-Crespo, G. Factors Associated with Psychological Flexibility in Higher Education Students: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125557

Mursalzade G, Escriche-Martínez S, Valdivia-Salas S, Jiménez TI, López-Crespo G. Factors Associated with Psychological Flexibility in Higher Education Students: A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125557

Chicago/Turabian StyleMursalzade, Goshgar, Sara Escriche-Martínez, Sonsoles Valdivia-Salas, Teresa I. Jiménez, and Ginesa López-Crespo. 2025. "Factors Associated with Psychological Flexibility in Higher Education Students: A Systematic Review" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125557

APA StyleMursalzade, G., Escriche-Martínez, S., Valdivia-Salas, S., Jiménez, T. I., & López-Crespo, G. (2025). Factors Associated with Psychological Flexibility in Higher Education Students: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 17(12), 5557. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125557