Abstract

Addressing the pressing global challenge of environmental sustainability, this study investigates novel pathways through which egoistic motivations—specifically personal health benefits, economic advantages, and perceived social status—influence green purchasing behavior among Chinese consumers. Employing an integrated approach that combines the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and self-identity theory (SIT), the research analyzes data from 361 Chinese consumers using advanced statistical techniques, including structural equation modeling (SEM). The findings reveal unique insights: personal health benefits and economic advantages emerge as significant drivers of green purchasing behavior, while perceived social status exerts an indirect effect through symbolic benefits. This study breaks new ground by demonstrating the dual mediating role of symbolic and functional benefits in linking egoistic motivations to green purchasing behavior. The results underscore the importance of developing marketing strategies that highlight personal health and economic savings, complemented by symbolic benefits, to effectively promote green products. Policymakers are encouraged to incorporate these nuanced motivations when designing incentives and regulations to enhance sustainable consumption practices.

1. Introduction

In recent years, escalating environmental challenges, such as climate change, resource depletion, and pollution, have intensified the need for sustainable consumption behaviors. Green purchasing behavior (GPB), typically defined as the adoption of eco-friendly products that minimize environmental harm, is widely recognized as a critical means to mitigate these issues. However, despite growing environmental consciousness among consumers, a persistent intention–behavior gap undermines the effectiveness of these initiatives [1,2]. This gap suggests that while consumers may express strong pro-environmental attitudes, these do not necessarily translate into actual purchasing behaviors.

To address this gap, structural interventions such as informational campaigns, green labeling, and economic incentives have been extensively employed. Nevertheless, He and Li [3] reveal through a systematic review that these externally oriented interventions often fail to produce sustainable behavioral change, primarily because they overlook consumers’ intrinsic motivations. Furthermore, Do and Do [4] demonstrate that activating social norms can temporarily boost green consumption, but the effects tend to diminish once normative pressures are removed. These findings indicate that while structural interventions have their merits, they are insufficient in isolation. Psychological mechanisms, particularly self-interest-driven benefit perceptions, may play a critical complementary role. Therefore, this study shifts attention toward internal motivational pathways, seeking to enrich the intervention-oriented literature with a motivational mediation framework.

This gap highlights the need to understand not only the drivers of green consumption but also the psychological mechanisms that explain why consumers follow through—or fail to follow through—on their intentions.

Much of the existing literature emphasizes altruistic motivations, such as environmental concern, moral obligations, and ethical responsibility, as primary drivers of green purchasing behavior. Recent research, however, suggests that while altruistic concerns remain important, they may not fully account for the complexities of actual consumer behavior. Dong and Huang [5] find that consumers often prioritize tangible personal benefits, such as product quality and health improvements, over abstract environmental ideals. Similarly, Kumar and Pandey [6] argue that social influence processes, particularly those mediated through social media and electronic word-of-mouth, blend altruistic values with egoistic considerations. Consequently, understanding green purchasing behavior necessitates a more comprehensive framework that incorporates both altruistic and egoistic motivations.

Within egoistic motivations, personal health benefits (PHB), perceived economic advantages (PEA), and perceived social status (PSS) have gained increasing scholarly attention [7,8]. Consumers are not only drawn to green products for their environmental attributes but also for the direct benefits they confer, such as health protection, cost savings, or enhanced social image. Dong and Huang [5] emphasize that consumer evaluations of green products frequently hinge on functional attributes directly related to personal utility rather than solely on environmental friendliness. In China’s emerging consumer market, characterized by rapid socio-economic transitions, these egoistic evaluations appear particularly influential, where individual health, financial prudence, and social recognition are critical consumption drivers.

The influence of these egoistic motivations is often mediated by symbolic and functional benefits. Symbolic benefits refer to the intangible rewards associated with green purchases, such as enhanced self-image, social recognition, or alignment with one’s ethical identity. Functional benefits encompass tangible advantages, such as improved health outcomes, cost savings, or superior product performance. Liang, Wu, and Du [9] stress that consumers’ interpretations of symbolic and functional benefits are context-dependent, shaped by factors such as environmental literacy, personal values, and socio-economic status. Thus, examining how egoistic motivations translate into green purchasing behavior through symbolic and functional mediators can offer richer and more nuanced insights into consumer psychology.

Despite growing recognition of the mediating roles of symbolic and functional benefits, few studies have systematically examined how egoistic motivations interact with these mediators to influence green purchasing behavior, particularly in emerging markets like China, where cultural norms and economic realities differ significantly from those in developed countries. Jawed et al. [10] highlight that sustainable consumption motives vary considerably between different consumer groups, reinforcing the need to contextualize motivational models. Furthermore, Wu et al. [11] find that among Generation Z consumers in China, symbolic and functional values influence green hotel visit intentions differently, depending on perceived social identity and practical utility. These findings suggest that the interactions among motivations, mediators, and behaviors are highly context-sensitive and merit closer empirical scrutiny.

Against this backdrop, this study develops and empirically tests a theoretically grounded model that examines how egoistic motivations—specifically personal health benefits, perceived economic advantages, and perceived social status—impact green purchasing behavior through the mediating roles of symbolic and functional benefits. Applying this framework within the Chinese market context enables the validation of egoistic motivational influences while also illuminating the nuanced mechanisms by which these motivations operate via symbolic and functional pathways.

The contributions of this study are threefold. First, it advances theoretical understanding by integrating egoistic motivations with symbolic and functional benefits into a unified explanatory model of green purchasing behavior, addressing a notable gap in the sustainability literature. Second, it provides empirical evidence from an emerging market context, enriching a field predominantly focused on developed economies. Finally, it offers actionable practical implications for marketers, policymakers, and sustainability advocates, suggesting that emphasizing personal benefits—such as health improvements, financial savings, and social prestige—can more effectively bridge the intention–behavior gap and promote eco-friendly purchasing behaviors.

2. Theoretical Foundations

In research on green consumer behavior, understanding consumer motivation and benefit recognition is crucial for explaining their purchasing decisions. Green products are generally defined as products that minimize environmental harm throughout their entire life cycle, from production to disposal, while simultaneously offering tangible benefits such as improved health, economic savings, and social prestige to consumers [5,8]. This dual-focus definition highlights that modern green consumption is motivated not only by altruistic environmental concerns but also by egoistic self-benefits, aligning closely with consumer decision-making processes in diverse cultural contexts.

D’Adamo [12] emphasizes that green consumption is driven not only by functional benefits, such as environmental advantages, but also by symbolic benefits, where consumers express their social responsibility and personal values through their purchasing choices. This perspective provides a theoretical foundation for this study, particularly in exploring the interplay between functional and symbolic benefits when consumers pursue sustainable products. Similarly, van Tulder [13] investigates the role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in enhancing the symbolic value of brands by conveying social values and environmental commitments, thereby influencing consumer purchasing behavior. Rubáček [14] further argues that consumers’ green purchasing decisions are shaped not only by environmental benefits (functional benefits) but also by social identity factors, particularly among those who seek to display their personal identity through green consumption. This dual motivation is fully explored in this study, which aims to understand how environmental and social identity factors drive consumers’ green purchasing intentions.

Furthermore, Hála [15] highlights the significant role that political and legal frameworks play in shaping consumer green purchasing behavior. Legal regulations such as eco-labeling and green procurement policies can significantly enhance consumer awareness and acceptance of green products. Jawed et al. [10] extend this understanding by emphasizing that regulatory-driven certifications not only standardize green product claims but also elevate the symbolic credibility of green consumption choices. Green policies and legal frameworks not only shape the market supply and consumer choice environment but also foster societal expectations for sustainable consumption, which in turn translate into symbolic benefits for consumers. For instance, businesses that adopt eco-friendly certifications and labels can communicate their environmental commitments, thereby establishing a strong sense of social responsibility and environmental awareness among consumers. This shift transforms green consumption into more than just a functional choice, making it a symbol of social identity. Thus, this study incorporates these theoretical frameworks to further explore the roles of functional and symbolic benefits in consumers’ green purchasing decisions, while evaluating how policies and legal factors, through societal expectations, influence consumers’ green purchasing intentions.

To position this study within the broader scholarly context, we reviewed recent international research published in the past few years that explores the psychological and value-based mechanisms driving green purchasing behavior. These studies examine egoistic motivations—such as health, economic, and status concerns—as well as the mediating roles of symbolic and functional benefits. Table 1 summarizes their thematic focus and main findings.

Table 1.

Key studies on green purchasing.

2.1. Theoretical Basis for Green Purchasing Behavior

Green purchasing behavior (GPB) has garnered extensive academic attention due to its role in promoting sustainability and reducing environmental harm. However, to develop a deeper understanding of GPB, it is essential to establish a robust theoretical foundation that comprehensively explains the psychological, social, and economic drivers influencing consumer behavior. This study adopts an integrated approach by drawing on three key theories: the theory of planned behavior (TPB) [27], self-identity theory (SIT) [28], and value-based theory [29]. Together, these frameworks offer a multidimensional perspective, addressing the interplay between egoistic motivations (personal health benefits, perceived economic advantages, and perceived social status) and the mediating roles of symbolic benefits (SB) and functional benefits (FB) in shaping green purchasing behavior.

Recent empirical studies further validate the relevance of these frameworks in green consumption contexts. For example, Dou, Zhao, and Wang [2] integrated TPB and moral emotion theories to explain sustainable purchasing behaviors, emphasizing the importance of internalized motivations beyond perceived behavioral control. Similarly, Wu et al. [11] applied an extended TPB model incorporating identity and symbolic factors to predict Chinese consumers’ green hotel visit intentions. These developments support the expansion of traditional models by including egoistic and symbolic pathways, as proposed in this study.

2.1.1. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) is one of the most widely applied theoretical frameworks for explaining and predicting individual decision-making. It posits that behavioral intentions—and ultimately behaviors—are shaped by three components: attitudes toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [27]. In the context of green purchasing behavior (GPB), TPB offers valuable insights into how personal beliefs, social pressures, and control perceptions jointly influence sustainable consumption.

In this study, TPB is partially adopted to frame the attitudinal and normative dimensions influencing GPB. Rather than replicating the full original structure of TPB, the model reconfigures its components through theoretically grounded proxy variables. Specifically, egoistic motivations—including perceived economic advantages (PEA), personal health benefits (PHB), and perceived social status (PSS)—are used to operationalize attitude-related and norm-related factors, following recent adaptations of TPB in sustainability research [2,11,22]. These modifications are in line with studies suggesting that individual behavioral intentions in pro-environmental contexts often stem from internalized outcome expectations rather than abstract attitudinal constructs.

Attitudes Toward Behavior.

Attitudes refer to an individual’s overall evaluation of the behavior and its anticipated consequences [27]. In green consumption, this dimension is reflected in motivations that emphasize direct and personal benefits, such as improved health and economic savings. Prior studies have consistently found that these egoistic considerations positively influence attitudes toward green products [16,17]. For example, the perceived health advantages of organic food or the financial efficiency of energy-saving appliances can foster favorable attitudes toward green purchasing.

Recent findings further suggest that the strength of these attitudes is closely tied to personal relevance, where self-interested benefits are often more salient than abstract environmental concerns [30]. However, the balance between egoistic and altruistic motivations remains context-dependent. While research in Western individualistic settings often emphasizes personal gain, collectivist cultures such as China may exhibit a stronger orientation toward community-oriented and environmental outcomes [31].

Subjective Norms.

Subjective norms describe the perceived social expectations surrounding a particular behavior [27]. In this study, subjective norms are reflected through the concept of perceived social status (PSS), which acts as a normative signal in many emerging markets. Consumers often adopt green purchasing behaviors to align with socially desirable roles and enhance their status in socially conscious circles [8,21]. Green consumption becomes a form of social identity expression, especially in collectivist contexts where reputation and harmony with group norms are critical [10].

Several studies suggest that symbolic benefits derived from green consumption—such as ethical image and social prestige—reinforce normative influences, especially when consumers perceive environmental behavior as a moral obligation or a route to peer recognition [31]. Nonetheless, most existing studies focus on collectivist societies, leaving open the question of how subjective norms operate in more individualistic cultures. Comparative research could further explore whether normative pressure operates through social compliance or personal value signaling in different cultural contexts.

Theoretical Positioning and Model Justification.

While the traditional TPB explicitly includes attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, intention, and behavior, the current study selectively incorporates TPB components and reconceptualizes them via egoistic motivations as explanatory drivers. This selective approach is supported by recent extensions of TPB that include motivational constructs—such as personal benefit expectations and social value concerns—as mediators or antecedents of intention and behavior [22,30]. Therefore, although traditional TPB labels do not appear verbatim in the proposed model, their underlying theoretical logic is retained through empirically grounded proxies. This reconstruction allows the framework to better capture the motivational complexity of green consumption behavior in contemporary markets, especially in culturally diverse contexts.

By embedding egoistic motivations within the TPB framework, the model enhances its explanatory power and contextual relevance. This ensures that the theoretical backbone remains robust while also accommodating the empirical realities of green purchasing in markets where self-interest, symbolic signaling, and functional evaluation are major behavioral drivers.

2.1.2. Self-Identity Theory (SIT)

Self-identity theory (SIT) provides an important lens for understanding how identity and social recognition influence consumer behavior. According to SIT, individuals’ behaviors are shaped by their self-concept and their desire to project certain social roles, which may include ethical, social, or environmental roles [28]. In the context of green purchasing, individuals use eco-friendly behaviors as a means of signaling their identity, enabling them to express their ethical values, environmental responsibility, and social status. This theoretical lens is particularly relevant in sustainability contexts where consumption is increasingly used as a tool for self-expression and social differentiation [8,26].

Symbolic benefits are central to SIT because they reflect the intangible psychological and social rewards consumers obtain from expressing self-identity through behavior. Consumers often perceive green products as symbols of moral superiority, social recognition, and commitment to sustainability [32,33]. This symbolic dimension helps explain why some consumers engage in sustainable consumption even when functional benefits, such as price or performance, are not obviously superior. Particularly in collectivist cultures, such as China, green consumption can serve as a vehicle for affirming one’s conformity with prevailing societal norms and expectations [4,31]. By contrast, in individualistic cultures, identity signaling may be more closely tied to personal uniqueness or moral positioning. Therefore, this study not only employs SIT to explain how symbolic benefits emerge as a mediating mechanism but also positions this process within cross-cultural consumer psychology.

A key egoistic motivator connected to SIT is perceived social status (PSS), which has been frequently examined in the context of “conspicuous conservation” [21]. Consumers may use environmentally responsible behaviors—such as purchasing luxury hybrid vehicles or high-end eco-friendly brands—to signal wealth, social consciousness, and modern values [10,17]. The perceived link between green products and prestige renders PSS a particularly relevant construct for emerging markets, where social mobility and status anxiety are salient concerns [34]. However, few studies have systematically explored how PSS translates into actual green purchasing behavior through identity-relevant mediators such as symbolic benefits, especially in comparative cultural contexts. This study addresses that gap by conceptualizing PSS not as a direct driver alone, but as a motivational input that activates symbolic pathways toward green consumption.

Importantly, SIT provides the theoretical foundation for proposing symbolic benefits (SB) as a mediating variable between egoistic motivations (PHB, PEA, PSS) and green purchasing behavior (GPB). Consumers motivated by health, savings, or status may internalize symbolic meanings through their purchases, aligning these benefits with their social identity and self-concept. As Sun, Liu, and Miao [20] show, identity-driven responses are highly sensitive to message framing and symbolic cues. By highlighting the psychological mechanism of symbolic meaning construction, this study explains not only why consumers are motivated to purchase green products, but also how these motivations are translated into action through identity alignment.

While SIT has been previously applied in consumer research, its integration with egoistic motivations in green consumption requires further elaboration. Prior studies often treat identity and egoism as distinct or even conflicting domains. However, recent interdisciplinary evidence suggests that egoistic motivations can operate synergistically with identity goals, particularly when green behavior satisfies both material and symbolic aspirations [3,35]. Therefore, this study extends SIT by demonstrating the compatibility between self-interest and social identity signaling in green purchasing, and by operationalizing symbolic benefits as a core psychological mediator in this relationship.

2.1.3. Value-Based Theory

Value-based theory [29] emphasizes that consumer behavior is driven by the pursuit of values that fulfill practical, emotional, and symbolic needs. In this framework, consumer decisions are influenced by both functional benefits (FB) and symbolic benefits (SB), which represent tangible and intangible rewards, respectively. These benefits form the evaluative criteria through which consumers assess the value of their choices. In the context of green purchasing behavior (GPB), FB and SB jointly shape motivations, with the former emphasizing utilitarian outcomes and the latter appealing to identity and emotional expression. While value-based theory has been widely applied in consumer behavior research, its extension to green consumption—particularly the interplay between functional and symbolic benefits—warrants further exploration [16,19].

Functional benefits refer to the practical advantages that consumers associate with green products, such as improved health, cost-efficiency, and environmental performance. Organic food, chemical-free personal care products, and energy-saving appliances are commonly perceived to deliver concrete benefits that justify their price premium. For example, organic food is often viewed as a safer, healthier alternative due to reduced exposure to harmful chemicals [16], while energy-efficient appliances lower electricity bills and reduce long-term maintenance costs [18]. These benefits are particularly relevant in markets where environmental risks are salient and where consumers seek not only individual utility but also broader societal impact [7,9]. However, existing studies often isolate functional drivers without sufficiently integrating them with symbolic pathways, leading to a fragmented understanding of green value perception.

Symbolic benefits, in contrast, address consumers’ identity, emotional expression, and social positioning. Consumers derive symbolic value when their purchasing behavior aligns with internalized values or generates positive social recognition. Green consumption thus functions as a channel through which individuals signal ethical commitment, social awareness, or environmental concern [8,32]. Purchasing sustainable fashion or driving a hybrid car, for instance, can serve both as an eco-friendly choice and as a statement of personal or social identity [32]. In collectivist societies, symbolic benefits may be further amplified by strong social norms and cultural expectations around environmental responsibility [4,31]. However, symbolic value does not function in isolation—it often complements or enhances the perceived utility of functional attributes. For instance, Sun, Liu, and Miao [20] show that symbolic and practical appeals interact in complex ways depending on message framing and personal involvement.

This dual structure of FB and SB offers a theoretical justification for using them as mediating variables in the relationship between egoistic motivations (e.g., personal health, economic advantages, and social status) and green purchasing behavior. Consumers do not act purely on internal motivations; rather, they translate such motivations into action when those motivations are perceived as valuable—either functionally, symbolically, or both. Recent studies support this mediation logic: Jawed et al. [10] emphasize that symbolic interpretations often elevate product relevance among new green consumers, while He and Li [3] suggest that effective interventions target both utilitarian and identity-driven motivations to stimulate behavior change.

Thus, the present study expands on value-based theory by integrating FB and SB as dual mediators that bridge the gap between egoistic motivations and GPB. This approach offers a more nuanced understanding of consumer decision-making by recognizing that value perception is multi-layered and shaped by both practical outcomes and symbolic interpretations.

2.2. Green Purchasing Behavior and Consumer Motivations

Green purchasing behavior has been extensively explored in the consumer behavior literature, with multiple theoretical perspectives explaining the factors influencing eco-friendly consumption. Consumers’ decisions to purchase green products are shaped by various intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, including egoistic motivations (personal health benefits, perceived economic advantages, and perceived social status), environmental awareness, perceived benefits, and social influences [25]. Traditional research highlights that consumers face several barriers when making sustainable choices, such as price sensitivity, skepticism toward green claims, and perceived inconvenience [24]. However, recent studies have shown that these challenges can be mitigated through enhanced economic, emotional, and symbolic value perceptions [36]. Egoistic motivations in green purchasing behavior stem from the consumer’s self-interest, including financial savings (perceived economic advantages), health benefits (personal health benefits), and status signaling (perceived social status) [37]. Research has established that consumers engage in green consumption when they perceive it as economically beneficial, emotionally rewarding, or enhancing their social image [38]. In contrast, individuals with lower environmental concern and knowledge may be reluctant to engage in sustainable behavior unless it aligns with their self-interest [39].

In China, where social status and symbolic consumption play a significant role in consumer decision-making, green product purchases often serve as a means of self-expression and social identity reinforcement [40]. This aligns with the findings of Testa et al. [25], who suggest that green products, particularly in markets like organic skincare and premium agri-food products, are perceived as status-enhancing symbols.

2.2.1. Health-Conscious Motivations and Green Purchasing Behavior

Personal health benefits (PHB) represent one of the most compelling motivations driving green purchasing behavior. Consumers increasingly prioritize their health when choosing products, especially in contexts where environmental degradation and food safety scandals have heightened concerns [19,31]. Green products, such as organic food, natural cleaning products, and chemical-free cosmetics, are perceived as safer alternatives that contribute to physical well-being. This perception is reinforced by health-focused marketing strategies that emphasize the absence of harmful chemicals and toxins, which has been shown to influence consumer attitudes positively [33,41].

For example, studies conducted in emerging economies have demonstrated that health-conscious individuals are more likely to adopt green products due to their perceived direct health improvements [13]. In China, concerns over air pollution and food safety have further strengthened the link between PHB and green consumption [31]. As such, consumers view green products as a form of preventive healthcare, leading to higher purchasing intentions.

Moreover, health benefits act as intrinsic motivators, aligning with individuals’ self-interest and rational decision-making processes. According to TPB, attitudes toward a behavior (such as purchasing eco-friendly products) are influenced by its perceived outcomes. Health-conscious attitudes, therefore, drive consumers to engage in green purchasing as a means to improve their quality of life [39]. Thus, we introduce a first hypothesis:

H1.

Personal health benefits (PHB) positively influence green purchasing behavior (GPB).

2.2.2. Economic Considerations as Drivers of Green Consumption

Perceived economic advantages (PEA) are another critical egoistic motivation that drives green purchasing behavior. Economic benefits include cost savings, energy efficiency, and long-term financial gains that consumers associate with eco-friendly products [9,17]. For instance, energy-efficient appliances and electric vehicles offer substantial savings on electricity and fuel costs, making them economically attractive choices. Research has consistently shown that consumers in price-sensitive markets are particularly motivated by these economic considerations [30].

In emerging economies, where financial constraints often dictate purchasing decisions, economic benefits can outweigh altruistic motives. For example, Mohammadi et al. [16] found that consumers in developing markets prioritize green products primarily for their economic utility rather than environmental concerns. Similarly, research by Jaiswal and Kant [18] demonstrates that perceived long-term savings act as a rational justification for green consumption.

From a TPB perspective, perceived economic advantages strengthen consumers’ attitudes toward green products by providing tangible benefits that align with self-interest [12]. These advantages also enhance perceived behavioral control (PBC), as consumers are more likely to adopt eco-friendly products when they are affordable and cost-effective [33]. Therefore, we introduce a second hypothesis:

H2.

Perceived economic advantages (PEA) positively influence green purchasing behavior (GPB).

2.2.3. The Role of Social Status in Driving Green Choices

Perceived social status (PSS) reflects the symbolic value consumers derive from green purchasing. Green products often serve as status symbols that signal social responsibility, ethical commitment, and wealth [8,21]. Individuals purchase eco-friendly goods not only for their functional utility but also to enhance their social image and gain social approval. This is particularly relevant in collectivist cultures, where societal norms and peer influence play a significant role in shaping behavior [31].

Research has shown that symbolic consumption, driven by the desire for social recognition, is a powerful predictor of green purchasing behavior [32]. For instance, Abdo et al. [24] argue that consumers engage in green purchasing as a form of conspicuous conservation, using eco-friendly products to project an environmentally responsible identity. This aligns with self-identity theory, which posits that behaviors consistent with societal expectations enhance individuals’ self-concept [28].

Moreover, social status amplifies the influence of subjective norms in TPB, as individuals are more likely to adopt behaviors endorsed by their social groups [27]. The desire to align with societal expectations and gain prestige motivates consumers to prioritize green products over conventional alternatives [30]. Thus, we introduce a third hypothesis:

H3.

Perceived social status (PSS) positively influences green purchasing behavior (GPB).

2.2.4. Symbolic Rewards in Promoting Green Purchasing Behavior

Symbolic benefits (SB) play a pivotal role in influencing consumers’ green purchasing behavior (GPB) by addressing emotional and identity-related motivations. Unlike functional benefits, which are largely grounded in tangible and practical outcomes, symbolic benefits center around the intangible rewards associated with consuming green products, such as social recognition, ethical satisfaction, and self-identity enhancement [8]. These benefits cater to individuals’ psychological needs for status, pride, and social conformity, which have been shown to significantly influence purchasing behavior, particularly in socially and culturally driven markets. One of the key mechanisms underlying the symbolic appeal of green products is their role as status symbols. Green products signal an individual’s commitment to environmental responsibility and ethical values, which enhances their reputation and social standing [21]. This is particularly evident in collectivist cultures, where social norms and community expectations strongly influence personal decision-making [31]. For instance, purchasing eco-friendly goods such as electric vehicles, sustainable clothing, or organic products enables individuals to project a socially responsible image that aligns with societal expectations. Research has shown that green purchasing behavior is often motivated by the desire to conform to these social norms, as individuals seek approval and recognition from their peers [30,32].

The role of symbolic rewards can also be understood through self-identity theory (SIT), which posits that behaviors aligned with one’s self-concept and social identity are more likely to be adopted [28]. Symbolic benefits help reinforce consumers’ positive self-perception by enabling them to identify as environmentally responsible individuals. For example, individuals who purchase green products may derive a sense of pride and ethical satisfaction from their contributions to environmental sustainability [17]. This emotional reward not only validates their values but also strengthens their self-identity, leading to repeat behaviors and long-term commitment to green consumption. In this way, symbolic benefits serve as psychological reinforcements that bridge personal motivations, such as perceived social status (PSS), and actual behavior. Moreover, symbolic rewards are closely tied to the theory of conspicuous conservation, which suggests that consumers engage in visible pro-environmental behaviors to signal their social status and moral values to others [21,33]. For instance, displaying reusable shopping bags, driving electric cars, or supporting eco-friendly brands are not just functional actions but also symbolic statements that enhance one’s social image. In modern consumer societies, where identity and lifestyle are often expressed through consumption choices, green products offer an effective means for individuals to differentiate themselves and showcase their ethical consciousness [8]. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced among younger generations, such as millennials and Gen Z, who are more likely to adopt sustainable behaviors driven by social and peer influences [28,31].

Additionally, the interplay between symbolic benefits and subjective norms, as proposed by the theory of planned behavior (TPB), further amplifies the role of symbolic rewards in driving green purchasing behavior. Subjective norms refer to the perceived social pressures to perform or refrain from certain behaviors [27]. When individuals believe that their peers, family, or society endorse green consumption as an indicator of responsible citizenship, they are more likely to adopt such behaviors to gain social acceptance [18]. Symbolic benefits, therefore, act as intermediaries that connect egoistic motivations, such as perceived social status, to actual behavior by leveraging the influence of societal norms. Empirical evidence supports the significant role of symbolic benefits in green purchasing behavior. For example, Abdo et al. [33] found that symbolic rewards, such as social recognition and moral satisfaction, mediate the relationship between social identity and green product adoption. Similarly, Chwialkowska et al. [32] demonstrated that consumers perceive green products as symbols of ethical superiority, which enhances their social standing and purchasing intentions. In another study, Guan et al. [17] highlighted the importance of symbolic benefits in promoting green consumption, particularly in markets where environmental awareness is growing rapidly.

In summary, symbolic benefits represent a critical mechanism that translates egoistic motivations, such as perceived social status, into actionable behavior. By addressing consumers’ emotional and identity-driven needs, symbolic rewards not only enhance the perceived value of green products but also foster a deeper psychological connection between consumers and sustainable consumption practices. Based on the above discussion, we introduce a fourth hypothesis:

H4.

Symbolic benefits (SB) positively influence green purchasing behavior (GPB).

2.2.5. Practical Rewards and Functional Benefits in Green Purchasing

Functional benefits (FB) complement symbolic rewards by providing tangible and measurable advantages that directly influence green purchasing behavior. Functional benefits refer to the practical outcomes derived from using green products, such as improved health, cost savings, product efficiency, and long-term durability [9,29]. Unlike symbolic benefits, which fulfill emotional and identity-related needs, functional benefits appeal to consumers’ rational decision-making processes, making them essential drivers of green product adoption.

Health improvements represent one of the most prominent functional benefits associated with green products. Consumers often perceive green alternatives, such as organic food, chemical-free cosmetics, and eco-friendly household items, as safer and healthier options [16]. In regions where environmental degradation and pollution are significant concerns, such as China and India, health-related motivations play a critical role in driving green consumption [31]. For example, studies have shown that consumers who prioritize health-conscious behaviors are more likely to purchase green products as a preventive measure to reduce health risks associated with non-sustainable alternatives [18,30].

Cost savings and economic efficiency are additional functional benefits that motivate green purchasing behavior, particularly in emerging markets. Energy-efficient appliances, electric vehicles, and sustainable packaging offer consumers significant savings on energy, fuel, and long-term maintenance costs [17]. These financial advantages make green products a rational choice for cost-conscious consumers who seek value for money. From a theoretical perspective, the TPB suggests that perceived behavioral control, influenced by functional benefits such as affordability and efficiency, enhances consumers’ ability to adopt sustainable behaviors [12].

Functional benefits also address consumers’ utilitarian needs by offering superior product performance and efficiency. For instance, eco-friendly products are often designed to reduce waste, conserve energy, and improve functionality, which aligns with consumers’ practical expectations [9]. Research has shown that consumers are more likely to adopt green products when they perceive them as meeting or exceeding the performance of conventional alternatives [16]. This utilitarian value reinforces positive attitudes toward green consumption, as consumers can justify their purchasing decisions based on tangible outcomes.

In conclusion, functional benefits serve as a bridge between egoistic motivations, such as personal health benefits and perceived economic advantages, and green purchasing behavior. By providing measurable and practical rewards, functional benefits address consumers’ rational needs, enhancing their willingness to adopt sustainable products. Based on this analysis, we introduce a fifth hypothesis:

H5.

Functional benefits (FB) positively influence green purchasing behavior (GPB).

2.3. The Mediating Role of Symbolic and Functional Benefits

Symbolic benefits and functional benefits mediate the relationship between perceived social status and green purchasing behavior. Symbolic benefits, such as social prestige and perceived ethical responsibility, encourage consumers to adopt green products as status symbols [38]. On the other hand, functional benefits, including personal health benefits, perceived economic advantages, and durability, provide practical justifications for green consumption [37].

Prior studies emphasize that consumers weigh these benefits differently depending on product category, consumer values, and market context. For instance, Pagiaslis & Krontalis [39] found that consumers with strong pro-environmental beliefs prioritize functional benefits, whereas those with lower environmental engagement respond more to symbolic benefits. Additionally, recent work by Siddiqui et al. [40] highlights that consumers in emerging markets view green products as aspirational lifestyle choices rather than purely functional alternatives.

According to self-identity theory [28], individuals adopt behaviors that are congruent with their identity goals and desire for social recognition. In the context of green consumption, perceived social status (PSS) serves as a salient egoistic motivator, aligning with the symbolic role of consumption behaviors in expressing social identity [21,33]. This establishes the theoretical justification for including PSS as the core motivational variable.

The mediating role of symbolic benefits (SB) is directly derived from SIT, where consumers use green products to signal ethical values and gain social recognition [32]. Functional benefits (FB), in contrast, can be explained by value-based theory [29], as they include utilitarian rewards such as health improvements and financial efficiency [9,16]. The dual pathway reflects how both identity-driven and utilitarian motivations translate into behavior, offering a holistic explanation for green purchasing decisions.

Thus, the theoretical model integrates egoistic motivation (PSS) with dual mediators (SB and FB), guided by SIT and value-based theory, to explain green purchasing behavior (GPB). This structured linkage ensures that each variable serves a theoretically grounded role in the model, allowing for a coherent transition from abstract motivation to observable behavior.

2.3.1. The Pathway of Symbolic Benefits in Translating Motivations into Actions

Symbolic benefits refer to the intangible, identity-driven rewards associated with green product consumption, such as social recognition, ethical satisfaction, and status enhancement [8,21]. From the perspective of self-identity theory (SIT), individuals engage in behaviors that align with their self-concept and desired social roles. When consumers perceive personal health benefits (PHB), economic advantages (PEA), or enhanced social status (PSS) through green purchasing, symbolic benefits act as a bridge to align these motivations with their social image. For instance, Abdo et al. [33] demonstrated that symbolic benefits significantly mediate the relationship between social identity and green purchasing. In their study, consumers derived a sense of pride and societal approval from purchasing eco-friendly products, which in turn strengthened their purchasing intentions. Similarly, research by Chwialkowska et al. [35] highlights that individuals in developed markets perceive green products as symbols of ethical superiority, which reinforces their social standing.

Symbolic benefits are particularly pronounced in collectivist cultures, where societal norms and peer influence play a dominant role in shaping behaviors [30,31]. For example, in China, green purchasing is often motivated by the desire to conform to societal expectations of environmental responsibility. Consumers perceive that aligning their consumption choices with social norms enhances their reputation and status, thereby fulfilling their egoistic motivations [8]. Thus, symbolic benefits serve as an essential mechanism that converts egoistic motivations into green purchasing behavior. By acting as a psychological pathway, they fulfill individuals’ emotional and identity-driven needs while reinforcing their external self-image. Based on this discussion, we introduce a sixth hypothesis:

H6.

Symbolic benefits (SB) mediate the relationship between egoistic motivations (PHB, PEA, PSS) and green purchasing behavior (GPB).

2.3.2. Functional Rewards as a Bridge Between Motivations and Green Behavior

Functional benefits are the tangible, utilitarian rewards associated with green products, such as health improvements, cost savings, and product efficiency [16,25]. Unlike symbolic benefits, which are rooted in social identity, functional benefits appeal to consumers’ rational decision-making processes by providing measurable and practical outcomes [29,39]. For individuals motivated by personal health benefits (PHB), functional benefits act as a direct justification for green purchasing. For example, consumers perceive organic food and natural products as safer alternatives that contribute to long-term health improvements [17]. In a study conducted by Mohammadi et al. [16], functional benefits were found to mediate the relationship between health concerns and purchasing behavior, as consumers viewed green products as preventive measures to mitigate health risks.

Similarly, consumers driven by perceived economic advantages (PEA) often prioritize functional benefits, such as energy efficiency and cost savings, when making green purchasing decisions. Studies by Jaiswal and Kant [18] highlight that energy-efficient appliances, electric vehicles, and other sustainable products offer long-term financial benefits, which serve as a practical motivator for adopting green consumption practices. In emerging markets, where economic constraints influence purchasing decisions, functional benefits play a critical role in bridging egoistic motivations and behavior [25,30]. In addition, for individuals motivated by perceived social status (PSS), functional benefits provide a secondary layer of justification. While symbolic benefits enhance social image, functional benefits offer practical utility that strengthens the rational basis for green purchasing. This dual benefit further amplifies the influence of egoistic motivations on behavior [8,33].

Importantly, green attributes are not independent drivers but are inherently embedded within the broader structure of product functionality. According to the functionality value framework [10,20], consumers typically evaluate products across four dimensions: physical functionality (e.g., performance, eco-efficiency), economic functionality (e.g., cost savings), emotional functionality (e.g., ethical satisfaction), and add-on functionality (e.g., health and safety benefits). Green characteristics, such as energy efficiency, recyclability, and low chemical content, enhance each of these dimensions, thereby reinforcing the overall perceived value and exerting a significant influence on green purchasing behavior.

Therefore, functional benefits serve as an essential mediating mechanism that connects egoistic motivations with green purchasing behavior by providing tangible, utilitarian rewards. Based on this analysis, we introduce a seventh hypothesis:

H7.

Functional benefits (FB) mediate the relationship between egoistic motivations (PHB, PEA, PSS) and green purchasing behavior (GPB).

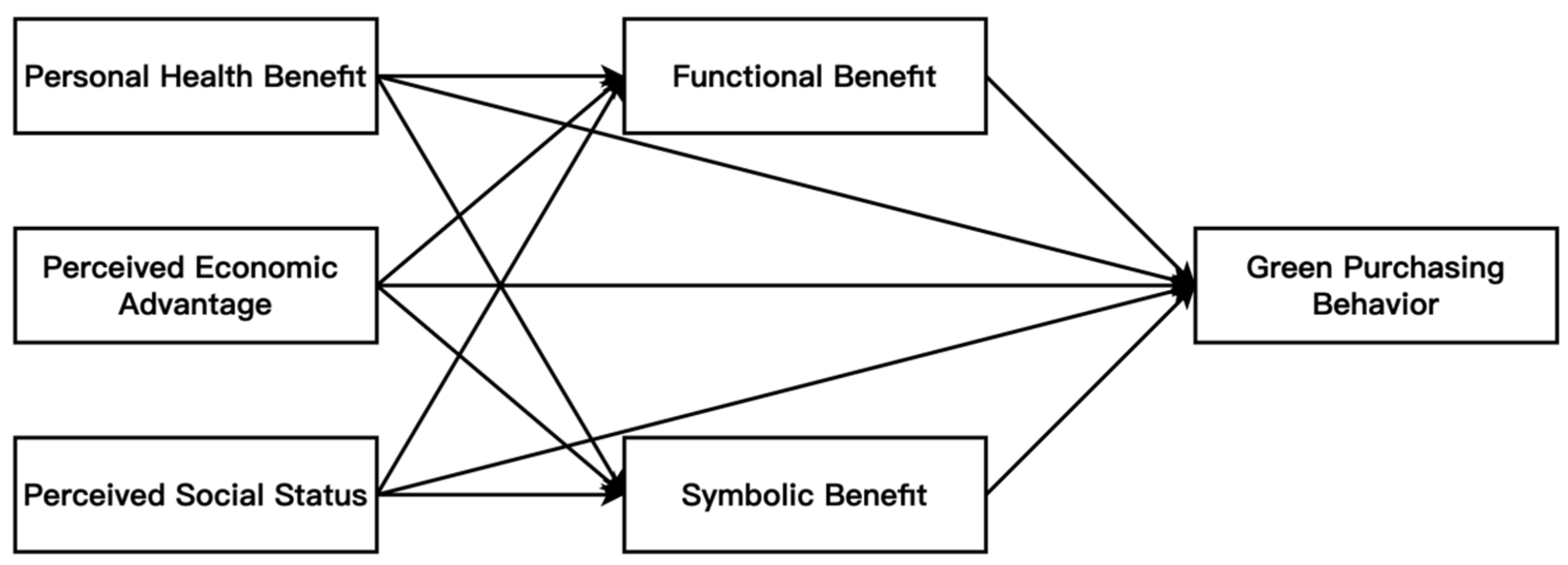

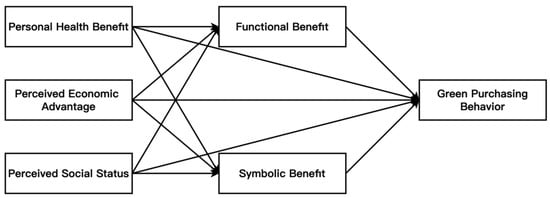

All seven hypotheses are illustrated in the proposed research framework shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Instrument Development and Measures

This study employed validated measurement scales from established literature to ensure alignment with theoretical constructs and to maintain clarity and relevance in capturing the core variables under investigation: personal health benefits (PHB), perceived economic advantages (PEA), perceived social status (PSS), symbolic benefits (SB), functional benefits (FB), and green purchasing behavior (GPB). A standardized five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree) was used across all items to facilitate consistency in responses and ease of analysis.

The questionnaire development process began with an extensive review of previous research to identify well-established scales relevant to the study constructs. For PHB, four items were adapted from Vermeir and Verbeke [42], capturing respondents’ perceptions of how green products positively impact their health, such as “Green products contribute positively to my physical well-being”. Types of PEA were assessed using three items from Thøgersen [43], reflecting the financial benefits of green purchasing, including “Purchasing green products reduces my long-term expenses”. Items for PSS were adapted from Griskevicius et al. [21], focusing on the social recognition associated with green consumption, such as “Using green products elevates my social reputation”.

The mediating variables, SB and FB, were operationalized using scales from Chen et al. [44] and Ottman [45], respectively. Symbolic benefits addressed the intangible outcomes of green consumption, such as social identity enhancement, with items like “Green products symbolize my commitment to sustainability”. Functional benefits captured practical attributes, including efficiency and reliability, with items such as “Green products are more reliable and effective.” Finally, GPB was assessed using four items from Roberts [46], focusing on consumers’ purchasing preferences, including “I often choose green products over conventional alternatives.”.

To ensure the validity and reliability of the instrument, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted on the final dataset using AMOS 26. CFA evaluated the measurement model’s properties, confirming strong factor loadings that supported the constructs’ convergent validity. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, with all constructs exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70 [47], demonstrating high internal consistency. Discriminant validity was verified by comparing the average variance extracted (AVE) values with the squared correlations between constructs, ensuring that each construct was distinct and conceptually independent. The full survey questionnaire is presented in Appendix A, and the measurement items for each construct are detailed in Appendix B.

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection Procedures

This study utilized a targeted sampling approach to collect data from Chinese consumers familiar with green products, ensuring the relevance and validity of the responses. Participants were recruited through the widely recognized Wenjuanxing platform, which is extensively used for academic surveys in China due to its accessibility and broad reach. The survey targeted individuals who had previously purchased or expressed interest in green products, aligning with the study’s focus on understanding the factors influencing green purchasing behavior.

The sampling technique adopted a convenience sampling strategy, which is commonly employed in exploratory studies of consumer behavior. While convenience sampling has limitations regarding generalizability, it is appropriate for examining theoretical relationships [48]. To mitigate potential biases, the survey was disseminated across various demographic groups, leveraging multiple online channels to ensure diversity in participant characteristics. Respondents were required to confirm their familiarity with green products to ensure the data accurately reflected the target population.

The final sample consisted of 361 respondents, exceeding the recommended sample size for structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses. According to Hair et al. [47], a sample size of at least 10 times the number of observed variables is necessary for robust parameter estimation. The demographic distribution of the sample was analyzed to ensure diversity across age, gender, education, and income levels. While not representative of the entire Chinese population, the sample provides sufficient variation to explore the hypothesized relationships within the target demographic.

To address potential sampling biases, demographic data were compared with national statistics to evaluate representativeness. Although exact alignment was not the primary goal, steps were taken to ensure that underrepresented groups were included. For instance, participants were recruited from different regions, including urban and rural areas, to capture a range of consumer behaviors.

The data collection process adhered to ethical guidelines, ensuring voluntary participation and informed consent. Respondents were assured of the anonymity and confidentiality of their responses, reducing the likelihood of social desirability bias. The online survey format was particularly advantageous for this study, offering geographic flexibility and minimizing interviewer bias. Additionally, the absence of financial incentives avoided potential response biases often associated with extrinsic motivations [49].

3.3. Statistical Analysis

To rigorously test the hypothesized relationships and evaluate the mediating roles of SB and FB in the relationship between egoistic motivations and GPB, this study employed a multi-step statistical analysis framework. The analyses were conducted using SPSS 27 and AMOS 26, leveraging their advanced capabilities for data exploration and hypothesis testing in behavioral research. The PROCESS macro [50] was used to conduct mediation analyses, ensuring robust estimation of indirect effects.

The data analysis began with preliminary checks to address potential issues related to data quality and common method variance. Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and correlations, were computed to explore the data’s underlying structure. Harman’s single-factor test was conducted using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in AMOS to assess common method variance. The results revealed that no single factor explained the majority of variance, mitigating concerns about common method bias [49]. Additionally, normality tests were performed to ensure that the data met the assumptions required for SEM.

The measurement model was evaluated through CFA to assess the reliability and validity of the constructs. Key indicators, such as factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE), were examined to confirm convergent and discriminant validity. All constructs demonstrated factor loadings above 0.70, CR values exceeding 0.80, and AVE values greater than 0.50, satisfying the recommended thresholds [47]. Model fit indices, including the comparative fit index (CFI = 0.956), the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI = 0.949), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.048), indicated a good fit between the measurement model and the data [51].

To test the structural relationships, the structural model was analyzed using AMOS. The direct effects of PHB, PEA, and PSS on GPB were estimated, alongside the indirect effects mediated by SB and FB. Bootstrapping with 2000 resamples was performed to compute confidence intervals for the mediation effects, providing robust statistical estimates. The results confirmed the mediating roles of SB and FB, with significant indirect effects observed for all egoistic motivations.

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics were derived to examine the demographic characteristics of the sample, providing foundational insights into the population under study. As summarized in Table 2, the sample was relatively gender-balanced, with 52.1% female and 47.9% male respondents. Regarding age distribution, the largest segment (27.1%) was aged 21–30 years, followed by the 31–40-year group (23.8%), indicating that young and middle-aged consumers dominated the sample. Educational attainment was varied, with 56.2% of respondents holding an associate degree or higher. Income distribution reflected a broad range, with approximately half of the respondents earning between 700–2100 USD monthly. Occupationally, the sample was diverse, consisting predominantly of employees (61.8%), civil servants (15.5%), students (13.3%), and a smaller proportion of retirees and unemployed individuals (9.4%). These demographic characteristics affirm the diversity and suitability of the sample for analyzing green purchasing behaviors across different consumer groups.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics.

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

The internal consistency of each construct was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha. All constructs exhibited high reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.810 to 0.901. Specifically, PHB showed an alpha of 0.874, PEA 0.810, PSS 0.875, FB 0.885, SB 0.867, and GPB 0.901. These results exceed the commonly accepted threshold of 0.7 [52], indicating excellent internal consistency across all constructs.

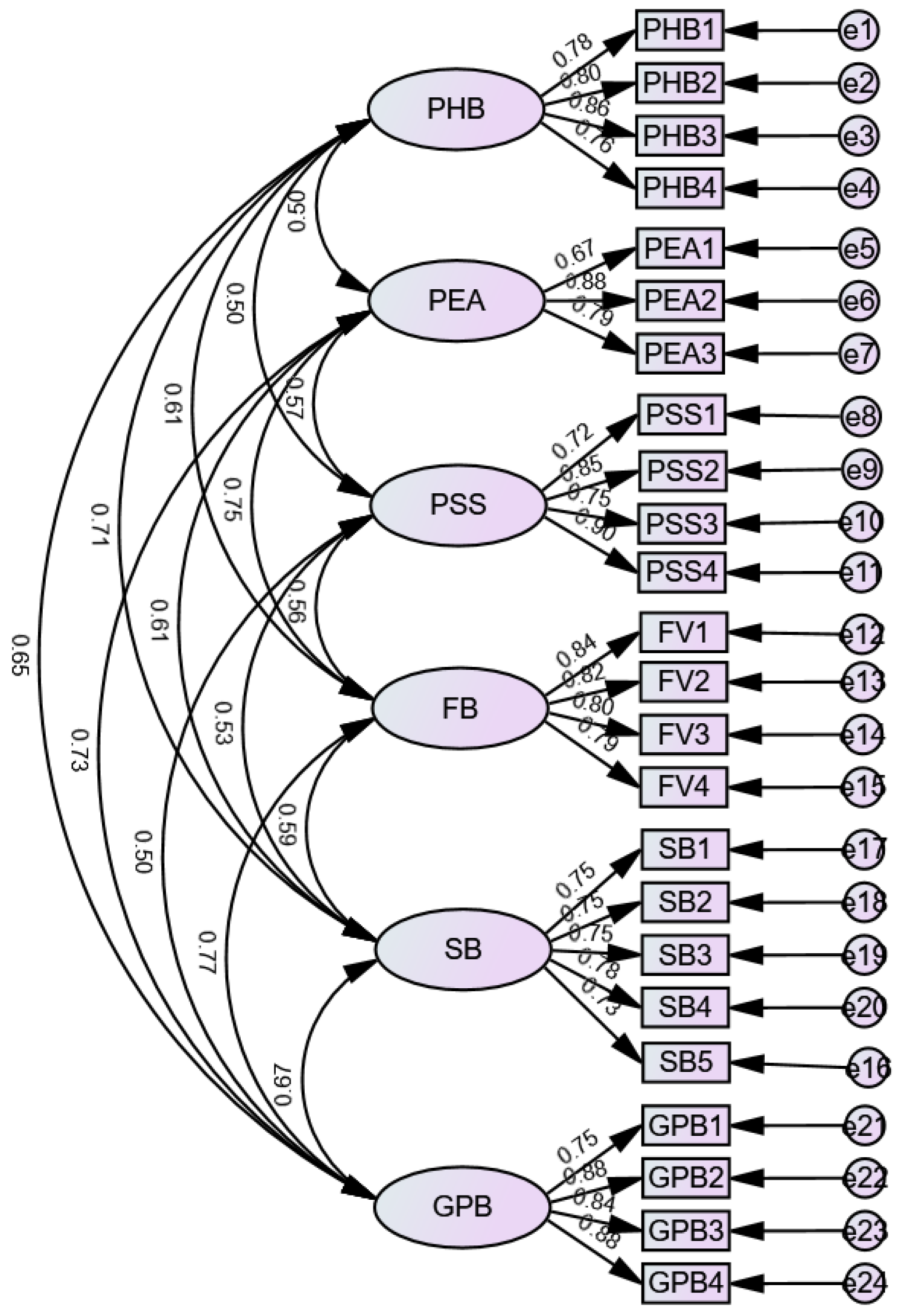

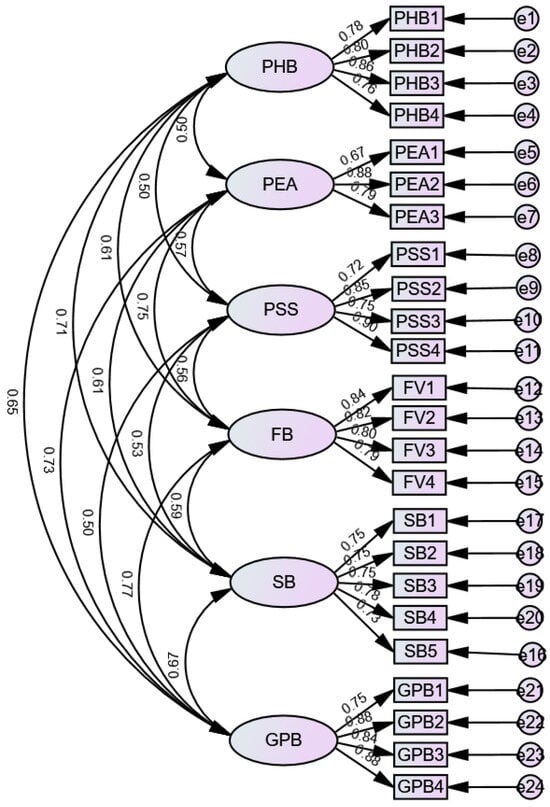

To validate the measurement model, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed. The fit indices, as shown in Table 3, revealed excellent model fit: CMIN/DF = 2.155, CFI = 0.952, TLI = 0.944, and RMSEA = 0.057, all within recommended thresholds [51]. The CFA model is visually summarized in Figure 2.

Table 3.

CFA model fit indices.

Figure 2.

CFA model diagram. Note: personal health benefits (PHB), perceived economic advantages (PEA), perceived social status (PSS), functional benefits (FB), symbolic benefits (SB), green purchasing behavior (GPB).

Convergent validity was confirmed through three criteria: all standardized factor loadings exceeded 0.70, average variance extracted (AVE) values were above 0.5, and composite reliability (CR) values surpassed 0.7 [47]. These results demonstrate that the indicators reliably measured their intended constructs.

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

To empirically validate the proposed conceptual framework, structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed following the preliminary assessment of data suitability. The normality test results confirmed that the skewness and kurtosis values of all observed variables fell within the acceptable range of ±1.5 [53], suggesting that the assumption of multivariate normality was met.

Pearson correlation analysis further revealed significant and positive correlations among all key variables, with coefficients ranging from 0.448 to 0.704, each significant at the 0.01 level. These findings provided preliminary support for the hypothesized relationships and justified the application of SEM for further analysis.

The overall model fit was assessed using a range of indices, and the results demonstrated an acceptable fit, as shown in Table 4. The chi-squared to degrees of freedom ratio (CMIN/DF) was 2.146, falling within the recommended range of 1 to 3. The comparative fit index (CFI = 0.952), incremental fit index (IFI = 0.952), and normed fit index (NFI = 0.914) all exceeded the commonly accepted threshold of 0.90, indicating a good model fit. The Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI = 0.944) also surpassed the minimum standard, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.056) remained below the cutoff value of 0.08, confirming the adequacy of model fit to the observed data.

Table 4.

SEM model fit indices.

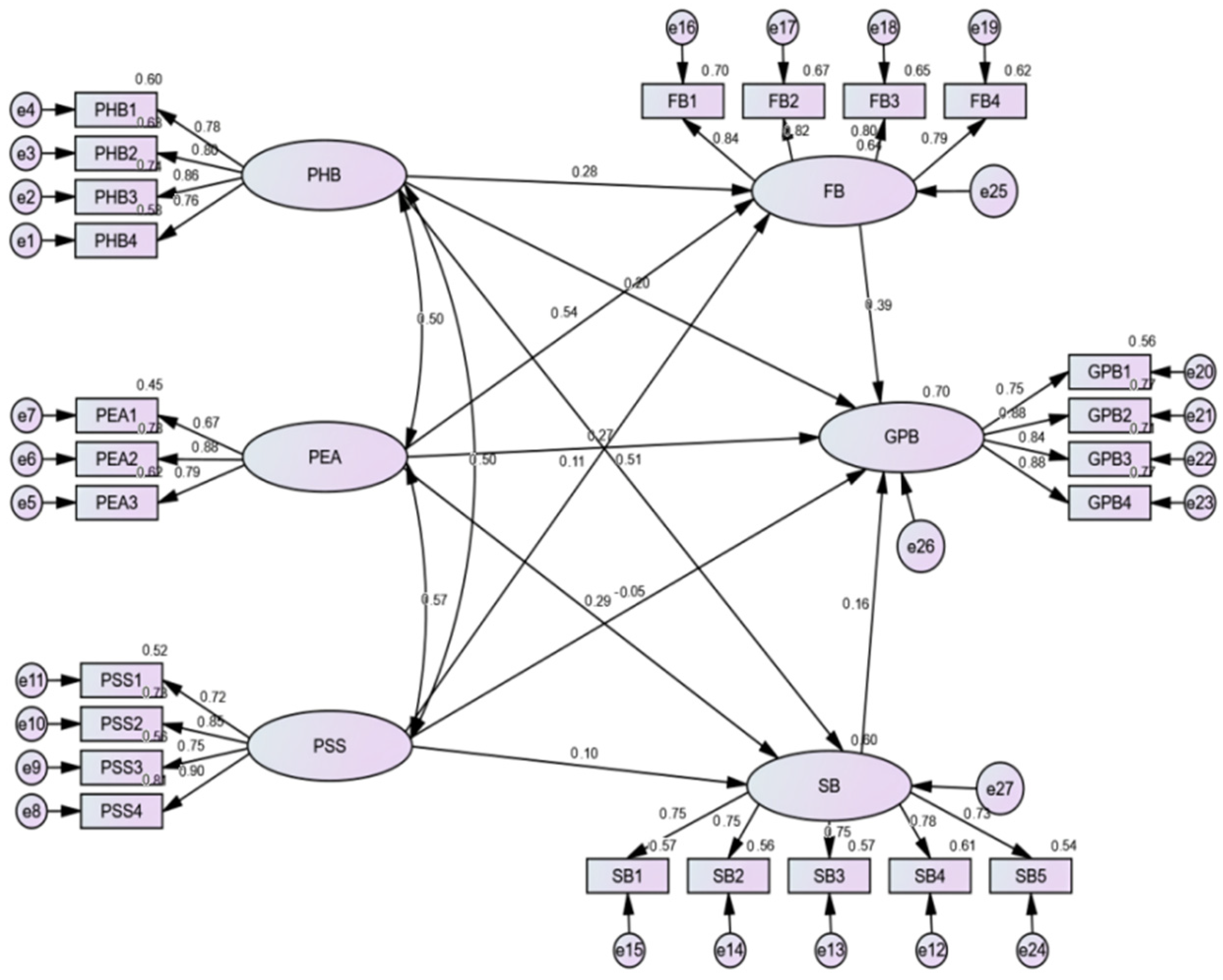

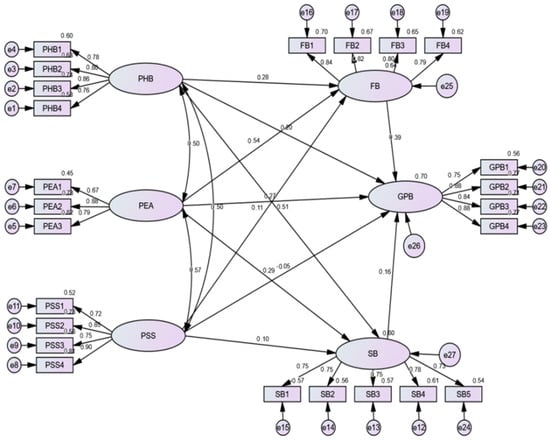

The standardized path coefficients, as illustrated in Figure 3, revealed that PHB significantly influenced FB (β = 0.276, p < 0.001) and SB (β = 0.515, p < 0.001). PEA had a strong positive effect on FB (β = 0.544, p < 0.001) and a moderate effect on SB (β = 0.292, p < 0.001). PSS significantly influenced FB (β = 0.111, p < 0.05) but had a non-significant relationship with SB (β = 0.104, p = 0.074).

Figure 3.

SEM model diagram.

Regarding GPB, FB exerted a substantial positive effect (β = 0.387, p < 0.001), while SB also positively predicted GPB (β = 0.158, p < 0.05). Direct effects from PHB (β = 0.195, p < 0.01) and PEA (β = 0.270, p < 0.001) to GPB were significant. However, the direct effect of PSS on GPB was non-significant (β = −0.047, p = 0.342), indicating that PSS may not independently drive green purchasing intentions.

In summary, the SEM results supported most of the direct hypothesized paths within the model and confirmed the good overall model fit. These results lay a robust empirical foundation for further hypothesis testing and mediation analysis in the subsequent sections.

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

The direct effects proposed in the conceptual model were evaluated by examining the standardized path coefficients and their significance levels based on the SEM results, as summarized in Table 5 and illustrated in Figure 3.

Table 5.

SEM path coefficients.

The analysis results revealed that PHB significantly and positively influenced FB (β = 0.276, p < 0.001) and SB (β = 0.515, p < 0.001), and exerted a direct positive impact on GPB (β = 0.195, p < 0.01). Similarly, PEA demonstrated a strong positive relationship with FB (β = 0.544, p < 0.001) and a moderate positive relationship with SB (β = 0.292, p < 0.001), along with a significant direct effect on GPB (β = 0.270, p < 0.001). These findings support the hypotheses that egoistic motivations linked to personal health and economic benefits are substantial direct drivers of green purchasing behavior.

In contrast, the direct path from PSS to GPB was not statistically significant (β = −0.047, p = 0.342), indicating that status concerns alone do not independently predict green purchasing actions. However, PSS showed a marginally significant effect on FB (β = 0.111, p < 0.05) and a near-significant effect on SB (β = 0.104, p = 0.074), suggesting the possibility of indirect influences through these benefit perceptions.

Both FB and SB exhibited significant positive impacts on GPB, with FB demonstrating a stronger influence (β = 0.387, p < 0.001) compared to SB (β = 0.158, p < 0.05). These results reinforce the critical roles of both practical and symbolic value perceptions in motivating sustainable purchasing behavior.

Overall, the hypothesis testing results validate most of the proposed direct relationships, while also revealing that the influence of social status on green purchasing behavior may primarily operate through mediated pathways rather than direct effects. This pattern highlights the multifaceted nature of consumer green behavior and provides a foundation for the mediation analysis that follows.

4.5. Mediation Analysis

The mediation analysis revealed that both functional benefits (FB) and symbolic benefits (SB) significantly mediate the relationship between egoistic motivations and green purchasing behavior (GPB), though their relative importance varies by antecedent. For perceived social status (PSS), the direct effect on GPB was not statistically significant, whereas both the FB and SB paths showed significant indirect effects, indicating full mediation. This suggests that status-driven motivations influence green behavior only when consumers perceive either symbolic alignment (e.g., social prestige) or functional utility (e.g., health/safety) from green products.

In contrast, personal health benefits (PHB) and perceived economic advantages (PEA) demonstrated partial mediation, with both direct and indirect effects remaining significant. PHB influenced GPB via FB (β = 0.2918) and SB (β = 0.2408), while maintaining a strong direct path (β = 0.3584), reflecting the dual role of self-care and social expression in health-related green choices. Likewise, PEA showed the most substantial total effect on GPB, combining strong direct effects (β = 0.4902) with meaningful mediation via FB (β = 0.3095) and SB (β = 0.1869). This pattern underscores that practical utility, especially in terms of cost-effectiveness and perceived quality, remains a primary motivator for green consumption, with symbolic aspects serving a complementary function.

Collectively, these results support the theorized dual-pathway model, where functional and symbolic benefits operate as distinct yet interrelated mechanisms linking egoistic drivers to green behavior. They also reinforce that while symbolic motivations matter—especially in status-oriented segments—functional considerations remain more consistently decisive in shaping actual green purchasing actions.

To maintain clarity and conciseness, detailed statistical outputs are not fully reported here but are available from the authors upon request.

5. Discussion

Our findings confirm that perceived social status significantly influences green purchasing behavior, with symbolic benefits and functional benefits serving as key mediating mechanisms. This outcome aligns with prior empirical evidence showing that egoistic, self-interest-driven motivations—including perceived social status, personal health benefits, and perceived economic advantages—are central determinants of green consumption [37,44] By simultaneously accounting for both symbolic and functional benefit pathways, our study advances the theoretical understanding of green purchasing behavior, moving beyond single-factor explanations and responding to recent scholarly calls for multidimensional modeling of pro-environmental behavior that encompasses both internal motivations and perceived value conversion mechanisms [2,3].

A central theoretical implication of our findings lies in the dual mediating role of symbolic benefits and functional benefits. Symbolic benefits—such as social prestige and identity signaling—exert a stronger influence among consumers with high status sensitivity, reinforcing Marcon et al.’s [38] proposition that green product attributes operate as social markers. This symbolic mechanism is particularly salient in cultural contexts like China, where consumer behavior is closely linked to social identity, self-presentation, and peer expectations [40]. On the other hand, functional benefits—such as product quality, health advantages, and economic value—mediate the relationship between egoistic motivations and green purchasing among consumers who are more concerned with instrumental utility than social signaling [39]. This bifurcation confirms that distinct motivational segments engage with green products via different benefit recognition pathways.

Furthermore, our study provides empirical insight into how clearly framed benefit perceptions can reduce green consumption barriers. Prior research has identified skepticism, price sensitivity, and perceived inconvenience as key obstacles to sustainable behavior [24]. Our results suggest that when symbolic or functional benefits are salient and well-communicated, these perceived obstacles are attenuated. In particular, when consumers see green consumption as a source of self-enhancement or personal well-being, they are more willing to engage in sustainable purchasing [25].

The findings also contribute to ongoing debates on the motivational balance between environmental concern and egoistic incentives. While the traditional literature often emphasizes environmental attitudes as primary predictors of green behavior, our results underscore the significant role of economic and emotional value perceptions—such as affordability, satisfaction, and perceived value for money—in motivating consumer action [36,37]. This dual-pathway insight reinforces the practical importance of designing green marketing strategies that simultaneously appeal to both self-interest and collective responsibility.

Building on the theoretical arguments of D’Adamo [12] and van Tulder [13], our study affirms that green product adoption is shaped by both tangible and intangible values. While functional benefits, such as carbon reduction or health improvements, provide rational justification, symbolic benefits allow consumers to express their environmental ethics and social responsibility. These two value types interact dynamically in shaping consumer choice. Echoing Rubáček [14], we find that especially among younger generations, green purchasing serves not only as a lifestyle preference but also as a form of identity construction—a way to embody and communicate personal responsibility within their social circles.

Finally, our findings extend existing frameworks by highlighting the institutional context in which symbolic meaning is constructed. Hála [15] emphasizes the role of eco-labels and regulatory policies in shaping public perceptions of environmental responsibility. We show that such institutional signals do not merely inform consumers but elevate the symbolic weight of green products. When firms obtain credible certifications or adopt green procurement standards, they transform sustainability from a functional attribute into a socially desirable identity marker. As such, our research integrates policy influence into the theoretical framework, emphasizing how macro-level expectations contribute to the symbolic conversion of green consumption choices.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

From a theoretical perspective, this study contributes to a more integrated understanding of green purchasing behavior (GPB) by explicitly connecting egoistic motivation—operationalized as perceived social status—with two distinct yet interrelated mediating mechanisms: symbolic benefits (SB) and functional benefits (FB). Prior research has often considered these benefits in isolation [38], but our model provides empirical evidence for their combined influence, offering a more holistic view of consumer decision-making in sustainability contexts.

Importantly, the study builds on and extends the theory of planned behavior (TPB) [27] by incorporating SB and FB as mediators, enriching the classical framework with motivational pathways that reflect both extrinsic (e.g., social prestige) and intrinsic (e.g., perceived utility) value systems. While TPB has typically focused on attitudinal, normative, and control-based predictors [41,54], our results highlight the role of benefit perception in translating intention into action. This aligns with recent extensions of TPB that emphasize reward-based and benefit-driven cognitive mechanisms as critical factors in reducing the intention–behavior gap [20,22].

The study further deepens the application of self-identity theory (SIT) [9] by emphasizing symbolic benefits as a channel through which consumers project their identity and social values in the marketplace. Green consumption, especially in status-oriented or collectivist cultures like China, often functions as a vehicle for identity signaling and moral positioning [10,21,23]. Our findings empirically support this symbolic pathway, demonstrating that consumers driven by egoistic motivations tend to favor green products not merely for environmental reasons, but as expressions of ethical self-image, social responsibility, and social distinction.

Simultaneously, the study reinforces the utility of value-based theory [29] by showing that functional benefits—such as health gains, economic savings, and product reliability—remain salient predictors of GPB. These tangible outcomes play a complementary role to symbolic rewards, reflecting a dual-motive structure in sustainability decision-making [5,45]. Recent studies also support this layered valuation model, suggesting that consumers increasingly make green choices based on a convergence of symbolic identity and practical benefit [5,9]. Our empirical model incorporates both domains, reinforcing the idea that green behavior is rarely driven by a single value orientation.

A further theoretical advancement lies in clarifying the intention–behavior gap in sustainable consumption. The integration of symbolic and functional benefits as mediators reveals how perceived value frames can reduce discrepancies between consumers’ pro-environmental attitudes and their actual purchasing behavior [55,56]. This addresses recent calls in the literature for identifying precise psychological mechanisms—such as symbolic affirmation or personal utility—that translate motivation into action [4,26].

In addition, the study provides context-specific insights by situating the theoretical model within the Chinese socio-economic and cultural environment. This not only enhances the cross-cultural relevance of TPB, SIT, and value-based theory but also addresses the empirical imbalance in sustainability research, which has traditionally focused on Western markets [54]. In collectivist societies, where group values, social identity, and public image are deeply influential, the symbolic pathway may have a magnified role in driving green behavior—an insight that invites further comparative exploration.

Finally, this study contributes to the theoretical discourse by offering a deductively grounded framework that links egoistic motivation with dual mediators rooted in established theories. The variable selection is not arbitrary; rather, it reflects a coherent integration of TPB, SIT, and value-based theory. This reinforces theoretical consistency and enhances the explanatory power of the model. Moreover, it underscores the importance of addressing consumer skepticism and behavioral barriers through value-based messaging strategies—such as highlighting social approval, health benefits, or cost-effectiveness—which can ultimately help convert sustainable attitudes into consistent green behavior [24,25].

To deepen the theoretical value of our findings, we incorporate the value package framework, which conceptualizes consumer evaluation of products through four interrelated dimensions: physical, economic, emotional, and add-on functionalities. This structure reinforces the idea that “green” is not an isolated consumption driver, but rather an integrated value embedded across multiple product functionalities [3]. By situating symbolic and functional benefits within this broader framework, we provide a more nuanced interpretation of green consumption behavior.

First, physical functionality refers to the tangible performance and health-related attributes of products. In the green consumption context, this includes the safety, technical efficiency, and environmental design of products such as organic foods and energy-efficient appliances, aligning with the functional benefits found in our study [16,17]. Second, economic functionality encompasses affordability, cost-efficiency, and perceived financial value, which significantly shape consumers’ utilitarian evaluations and drive their green purchasing intentions [37]. Third, emotional functionality is closely tied to symbolic benefits, involving personal satisfaction, social recognition, and ethical self-expression [8,10,21]. Our findings confirm that consumers frequently use green products to construct and signal environmentally responsible identities. Fourth, add-on functionality captures auxiliary values such as safety, ease of use, and environmental recyclability—elements that may be partially reflected in both symbolic and functional pathways and warrant more explicit operationalization in future models.

Interpreting our empirical findings through this four-dimensional lens enriches the explanatory power of our theoretical framework. It underscores that egoistic motivations, such as perceived social status or personal utility, do not operate in isolation but are manifested through consumers’ broader value-seeking behavior across product dimensions. This perspective helps bridge the motivational antecedents and product-specific evaluations in green purchasing behavior, and encourages future research to explore how different configurations of these functional dimensions influence consumption decisions across cultures, markets, and product categories.

5.2. Practical Implications

This study contributes to understanding how functional and symbolic benefits jointly influence green purchasing behavior and how legal, policy, and social identity factors shape consumer decisions. By building on frameworks from D’Adamo [12] and van Tulder [13], it offers practical insights into how both marketing and regulatory approaches can foster green consumption. Recent findings also support the importance of combining intrinsic (e.g., identity, pride) and extrinsic (e.g., affordability, performance) benefit appeals to enhance green product acceptance [20,57].

Consumers often weigh both benefit types—symbolic and functional—when making green choices. As environmental concern grows, the desire to express social responsibility and values through consumption becomes more salient. This shift urges firms and policymakers to leverage legal tools such as eco-labels and subsidies. Experimental research in China, for example, shows that higher environmental literacy and trust in certification systems increase consumer responsiveness to such cues [35].

Green consumption, however, is not only driven by individual motives but also by broader social and cultural factors. Therefore, further research should explore behavior across different regions and policy environments. He and Li [3] argue for policy designs that align behavioral interventions with social norms and awareness campaigns to support long-term behavioral change.

For practitioners, this study offers several actionable insights. First, marketers should highlight both the symbolic and functional dimensions of green products. Emphasizing symbolic value—such as social prestige and identity expression—can attract consumers seeking societal recognition [8,21]. Branding strategies that portray green products as lifestyle statements are especially effective in status-driven markets [4,58].