Abstract

Facing severe depopulation and aging, rural Japanese communities—particularly marginal settlements (genkai shūraku)—increasingly require revitalization strategies that integrate local culture and elder well-being. This study examines the Ōsawa Engawa Café, a community-led initiative in a mountainous tea-growing village, as a site of ikigai-zukuri—the active creation of life purpose among elderly residents. With the use of a mixed-methods approach, including spatial analysis, household surveys, and interviews, Chi-square Automatic Interaction Detection (CHAID) decision tree analysis was applied to identify factors shaping distinct household café operational states: Operating, Discontinued, and Never Operated. Qualitative findings reveal that support from local leaders, experts, and the government enabled the Ōsawa Engawa café’s launch. Broad household participation, often guided by elderly women, sustained the initiative by sharing local culture—such as engawa (verandas), Zairai tea (native variety), and omotenashi (hospitality)—thereby nurturing residents’ ikigai through daily engagement. Complementing these insights, the CHAID analysis revealed a hierarchy of influential factors: high-frequency support from out-migrated family members was the strongest predictor of continued operation; in the absence of such support, co-resident family cooperation proved essential; where both were lacking, agricultural engagement distinguished households that discontinued from those that never operated. Practically, the Ōsawa model offers a replicable, bottom-up strategy that activates the Rural Cultural Landscape (landscapes shaped by traditional rural life and culture, RCL) through community engagement grounded in cultural practices and elderly ikigai-zukuri, contributing to sustainable rural livelihoods. Theoretically, this study reframes ikigai-zukuri as a key socio-cultural pillar of community resilience in aging rural areas. Fostering such culturally embedded, purpose-driven initiatives is essential for building vibrant, adaptive rural communities in the face of demographic decline. However, the study acknowledges that the Ōsawa model’s success is rooted in its specific socio-cultural context, and its replication in other cultural settings may be limited without contextual adaptation.

1. Introduction

Rapid aging and depopulation pose profound challenges to the sustainability of rural communities globally, particularly undermining traditional livelihoods and social structures [1,2]. While linked to broader factors like globalization, this decline is fundamentally driven by the demographic transition [3,4] from high to low fertility and mortality rates manifesting acutely in rural areas [5,6]. The concentration of economic activities and population in urban centers, driven by disparities in employment, education, and services, further accelerates rural out-migration [7]. Particularly among younger generations, this migration intensifies existing challenges faced by rural areas [8]. This demographic shift, coupled with the erosion of traditional livelihoods and social structures, poses a fundamental threat to the well-being and sense of purpose of elderly residents who remain in rural communities. This global trend highlights the need for place-based rural revitalization strategies [9] that empower local elderly residents and foster their sense of “ikigai” [10] through community contribution, meaningful social roles, and strengthened regional connections [11].

Globally, rural revitalization has been pursued in ways that align with countries’ distinct resources, priorities, and socio-economic conditions. In the European Union, rural revitalization often emphasizes a holistic, place-based, and people-centered approach, recognizing the multifunctionality of rural areas and integrating economic, social, environmental, and cultural objectives [12,13]. Bottom-up, community-led initiatives and participatory planning are prioritized, leveraging local assets and strengthening social capital [7,14]. In contrast, the United States has tended to favor market-driven solutions, private-sector investment, and entrepreneurship, with a significant emphasis on attracting new residents through natural amenities and lower costs of living [15,16]. In many developing countries, including China, state-led strategies and top-down planning remain dominant, though there is increasing acknowledgement of the need for integrated approaches [17,18]. However, while such approaches are valuable, they often prioritize economic development and infrastructure over the socio-cultural needs of aging populations, such as cultural continuity, meaningful social roles, and a sustained sense of belonging [19].

Japan, confronting the world’s most rapidly aging population [20] and the unique challenge of marginal settlements (genkai shūraku) [21], faces extreme depopulation, offering a crucial context for exploring alternative approaches to rural revitalization. In these communities, where the elderly constitute a significant majority, the limitations of purely economic or infrastructure-focused strategies become particularly apparent [22]. This makes Japan not only a country in crisis, but also a vital context for rethinking how culturally grounded, elder-centered approaches can contribute to community resilience.

Japan highlights the importance of considering ikigai—a Japanese concept signifying a sense of purpose, meaning, motivation, and belonging often derived from meaningful activities and social contributions [10,11]. Research has linked ikigai to better mental health, psychological well-being, and healthy aging [23,24]. In response, the Japanese government has introduced ikigai-zukuri—welfare programs aimed at enhancing older adults’ life purpose (ikigai)—through activities such as hobby classes and fitness groups [25,26].

However, such efforts are mainly concentrated in urban and peri-urban areas and are rarely implemented in depopulated rural regions. This reveals a major policy gap, particularly given the severe aging and population decline in marginal settlements. Although rural older adults often report higher ikigai levels than urban ones [27], this does not signify a lack of need for support; rather, it underscores their potential to remain active contributors to their communities. In rural Japan, daily life is built upon strong emotional and social ties among families, neighbors, and local communities [27]. These relationships, as some studies suggest, help older adults—especially women—find ikigai through learning, cooperation, and practical work embedded in their local context [27,28]. Strengthening such locally rooted ikigai is therefore essential for fostering aging in place and sustaining marginal settlements.

Despite its importance, existing studies have largely overlooked the social and community dimensions of ikigai—particularly its role as a collective, culturally embedded process [29,30]. Addressing this gap, the present study examines how community-based engagement in a marginal settlement can foster ikigai among older adults, not merely as personal well-being, but as a mechanism of rural sustainability. To systematically explore this mechanism and the interplay of factors involved, this study develops and applies a multi-layered conceptual framework, which will be detailed in the following section.

We used a mixed-methods approach, including interviews with local residents, project managers, and visitors, as well as field observations, to investigate how older residents in Ōsawa—a small mountainous settlement in Shizuoka, Japan—cultivate ikigai through community-based engagement. Our focus was on elderly participants involved in the Engawa Café project, examining their sense of purpose and social involvement through café operation and daily interaction.

In this community-led project, elderly residents utilize traditional engawa (verandas) [31] to host temporary cafés, fostering ikigai-zukuri (enhancing life purpose) through meaningful participation embedded in local culture and everyday social exchange. By engaging in community life, elderly residents cultivate a sense of purpose, achievement, and belonging, transforming ikigai into a driver of community resilience and a pathway toward sustainable rural futures.

2. Research Framework

Traditional rural revitalization strategies in Japan, from early “chiiki kasseika” focused on large-scale infrastructure [32] to more recent “chihō sōsei” emphasizing urban–rural tourism and attracting new residents [33], often prove insufficient [9], particularly in aging, depopulating marginal settlements [34]. While potentially achieving short-term goals like infrastructure improvement or economic activity, these top-down approaches typically fail to tackle the root causes of rural decline—namely, structural economic changes, demographic shifts, and the subsequent erosion of sustainable local livelihoods [32,35]. Such approaches may neglect the persistent distinctiveness of rural life [36] and fail to grasp the complexities of blurred rural–urban interfaces [37], applying standardized, externally-driven models instead of recognizing and leveraging unique local strengths and capacities [38]. Critically, such strategies tend to undervalue or neglect the adaptive capacity embedded within the existing “domestic economy” [39] or “peasant economy” [40]—the traditional, flexible, family-based livelihood strategies incorporating diverse activities, such as local crafts, food processing, and small-scale tourism ventures, beyond formal agriculture [41,42] that persist in many marginalized communities. Consequently, critical underlying issues like the erosion of local culture [43], declining community cohesion [44], and impacts on elderly residents’ identity and self-worth [45] are often overlooked. Recognizing these limitations, this study explores ikigai-zukuri. Drawing from perspectives like the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [46], we define ikigai-zukuri as the active construction of life purpose through meaningful social participation and roles [47]. We argue that fostering ikigai-zukuri is crucial for sustainable livelihoods and community resilience, to systematically investigate how ikigai-zukuri contributes to community resilience within the complex realities of depopulating rural areas, and to capture the underlying dynamics, this study proposes and employs a conceptual framework specifically developed by the authors.

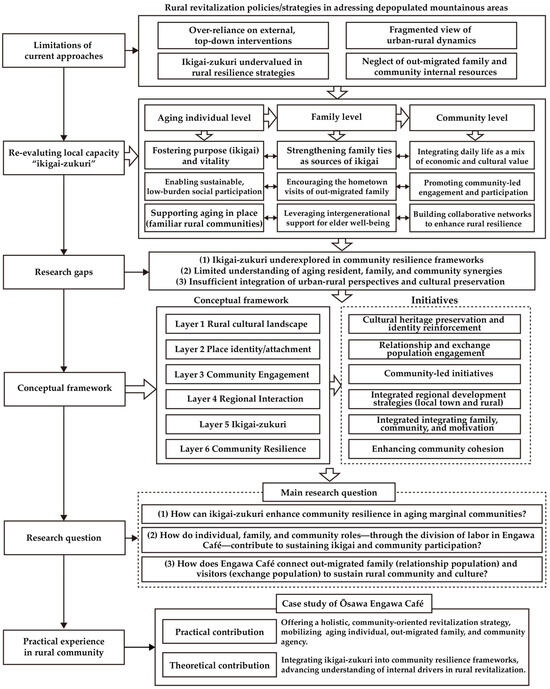

This proposed conceptual framework is structured into six interrelated layers (see Table 1 and Figure 1), elucidating the pathway through which ikigai-zukuri can be constructed and contribute to resilience in rural areas.

Table 1.

Conceptual framework: fostering ikigai-zukuri and community resilience in rural areas.

Figure 1.

Research framework: Ikigai-zukuri as a driver of community resilience in aging marginal settlements. “Kaso” refers to severe depopulation and aging in rural Japan; “Genkai shūraku” refers to marginal settlements (typically with over 50% of residents aged 65 or older). In this framework, “ikigai-zukuri” refers to the active creation of purpose and meaning in life through social participation in aging rural communities. “Relationship population” denotes out-migrated family members who maintain ties with their hometowns, while “exchange population” refers to visitors engaging in short-term stays and interactions with the community. The framework illustrates how re-evaluating local capacity through ikigai-zukuri addresses limitations of current revitalization approaches and provides a theoretical basis for understanding community resilience, examined through the Ōsawa Engawa Café case study. This figure was created by the authors.

The pathway begins with the foundational context: the Rural Cultural Landscape (landscapes shaped by traditional rural life and culture, RCL) (Layer 1), offering resources and foundation [48], and residents‘ deep Place Identity and Attachment (Layer 2), providing vital emotional grounding rooted in Ōsawa’s history [48,49]. This belonging fosters local participation motivation and serves as an enduring tie, drawing back out-migrated families for crucial support [50,51].

These foundations enable key mechanisms: Community Engagement (Layer 3), sustained by the interplay of local commitment and external family support; Regional Interaction (Layer 4) [3,9]; and the activation of local cultural practices. Residents find meaningful action by engaging with cultural elements—recognizing daily practices as valued assets and sharing them outward.

These mechanisms collectively enable the core process of ikigai-zukuri (Layer 5). This central meaning-making occurs as residents reaffirm cultural identity, foster social belonging, and exercise agency, converging everyday cultural practice with social connection and personal validation. This framework thus views community resilience (Layer 6) not just as an external goal but as intrinsically linked to the internal process of ikigai-zukuri [38,52]. The flourishing of ikigai enhances social and cultural dimensions of resilience (e.g., cohesion, continuity). Conversely, a resilient community supports ikigai-zukuri, creating a vital positive feedback loop (Figure 1).

Layers 1–2 support the conditions, Layers 3–4 enact the mechanisms, Layer 5 crystallizes the internal process, and Layer 6 captures the emergent outcomes (Table 1). This conceptual framework highlights three interconnected levels of participation (individual, family, and community) crucial for fostering ikigai-zukuri and community resilience. Grounded in this analytical structure, the present study aims to answer the following (Figure 1): (1) How can ikigai-zukuri enhance community resilience in aging marginal settlements? (2) How do individual, family, and community roles contribute to sustaining ikigai and participation? (3) How does the Engawa Café connect out-migrated families and visitors to sustain rural vitality and culture?

To explore these questions empirically, we conduct an in-depth case study of the Ōsawa Engawa Café. By examining ikigai-zukuri as emerging from sustained engagement across the layers of our conceptual framework within this specific context, we aim to offer a new way to conceptualize resilience in depopulated, aging settlements, thereby generating both practical insights and theoretical contributions (Figure 1).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.1.1. Ōsawa, a Traditional Tea-Growing Section in Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan

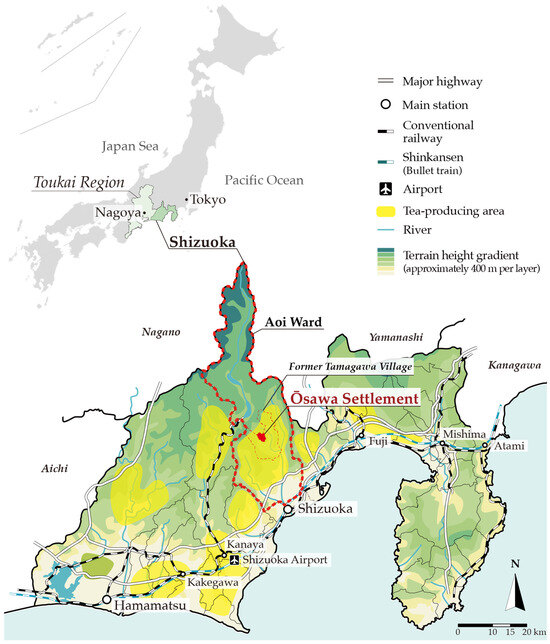

This study was conducted in Ōsawa, a small mountain settlement located in Aoi Ward, Shizuoka City, Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan. Located approximately one hour by car from the city center, Ōsawa is accessible only via winding mountain roads, which underscores its relative remoteness. As shown in Figure 2, Shizuoka Prefecture—situated in the Tōkai Region along the Pacific coast—is widely recognized as one of Japan’s most important tea-producing areas, with cultivation zones spread across diverse geographic settings, particularly in its upland regions.

Figure 2.

Location and Regional Context of the Ōsawa Settlement, Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan (Note: Base map and administrative boundaries are based on data from the Shizuoka Prefectural Government. Tea-producing areas are marked based on information from the Shizuoka Prefecture Tea Industry Promotion Division [53]. Visualized using Google Earth Pro (version 7.3)).

Aoi Ward, in the northern part of Shizuoka City, is renowned for producing Honyama tea and is often cited as the historical birthplace of tea cultivation in the prefecture (Figure 2). Within this area, the former Tamagawa Village is among the core production zones of Honyama tea. Although Tamagawa was later merged into Shizuoka City’s Aoi Ward [54], local identity and customary practices have remained closely tied to the former village framework.

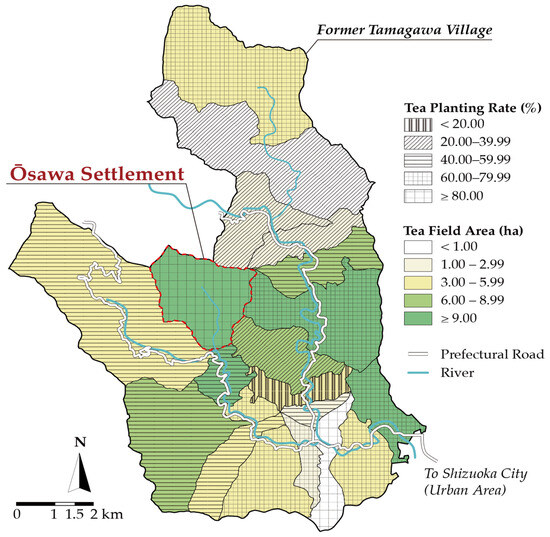

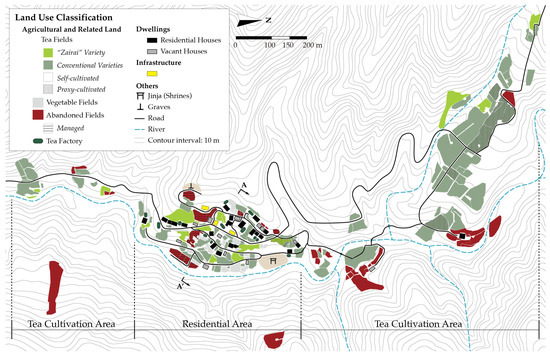

To better understand the spatial context of the Ōsawa settlement, including the distribution of tea fields and overall land-use patterns, a Geographic Information System (GIS)-based analysis was conducted using ArcMap 10.8 (Esri Inc., Redlands, CA, USA). For Figure 3, farmland parcel data published in 2022 by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) were used as the base layer [55]. Since this dataset includes all types of agricultural land without distinguishing tea fields, potential tea plots were first identified based on land-use symbols on the Standard Map provided by the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (GSI; last updated 1 April 2014, accessed via GIS tile server). These candidate plots were then cross-verified using Google Satellite imagery (last modified 6 December 2022), with reference to the 2023 cultivation status. Additional historical imagery was consulted to avoid misclassifying fields undergoing replanting or recent clearing. For Figure 4, the land-use and spatial structure of the Ōsawa settlement were mapped based on GSI’s Standard Map and field observation. Land cover was manually classified into agricultural, residential, and forest zones using satellite imagery interpretation and on-site verification.

Figure 3.

Tea field area and planting rate in the Tamagawa Region (source: authors, based on data from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) farmland parcel dataset, validated using GSI Standard Maps and Google Maps aerial imagery).

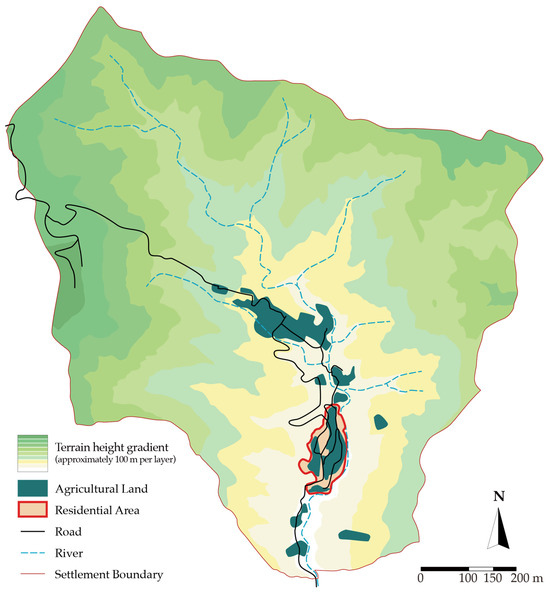

Figure 4.

Land use and spatial structure of Ōsawa settlement.

Ōsawa, located on the periphery of the former Tamagawa area, is believed to be the first settlement in the region to begin cultivating tea, with historical records dating back to 1606 [56]. Tea farming has remained the primary livelihood for local residents ever since. As shown in Figure 3, Ōsawa holds a central role in the region’s tea economy, with more than 9 hectares of tea fields and a planting rate exceeding 90%. These indicators reflect not only the scale of production but also the deep integration of tea cultivation into the community’s economy and identity.

Figure 4 illustrates the internal land-use structure of Ōsawa. It reveals a linear settlement pattern along the river valley, with residential areas clustered in the south and surrounded by agricultural land, predominantly tea fields. This stable, tea-centered production model has evolved through close interaction with the natural environment and has shaped a distinctive land-use system and agricultural landscape rooted in both ecological adaptation and everyday rural life.

3.1.2. Local Culture and Community Life

Ōsawa’s social fabric today reflects both deep-rooted traditions and urgent demographic challenges. In 1685, the settlement comprised 13 households, expanding to over 30 households by the Meiji period (1868–1912) [56,57]. However, like many rural communities in Japan, Ōsawa has experienced significant population decline. Today, only 22 households remain, and more than half of the residents are aged 65 or older [58], classifying the settlement as a “marginal settlement” [34].

Despite this demographic downturn, the village retains a highly cohesive community structure rooted in kinship and tradition. Due to its remote location and limited in-migration, the Ōsawa community has remained highly stable and is predominantly composed of two family lineages descended from the samurai of the Sanada clan [57]. This demographic stability, combined with close kinship ties and a long-standing reliance on tea cultivation, has fostered a dense social network and enduring cultural traditions. Everyday interactions such as exchanging greetings, and offering mutual assistance are common within the settlement. Though seemingly minor, these practices reflect a tightly knit local community built on emotional bonds and mutual dependence, which Nawata (1999) identifies as key elements of communal cohesion [59].

Within this social structure, multiple self-organized groups have emerged. Traditional organizations, such as the neighborhood association (chōnaikai) and women’s association (fujinkai), manage daily affairs, seasonal events, and collective decision-making [60]. In addition, since the 1960s, Ōsawa has maintained a specialized body: the Tea Industry Research Association (TIRA). This association holds annual tea evaluation contests to recognize top-performing tea farmers, fostering a culture of pride and excellence in tea quality. Each tea farmer takes great pride in their tea, and this sense of personal identity has endured even as market profits have declined. It was precisely this deep-rooted pride and sense of collective identity that enabled the association to quickly respond to the decline of the tea industry and become one of the key driving forces behind the Engawa Café initiative.

3.1.3. From Tradition to Local Innovation: The Community-Initiated Engawa Café

While tea farming has long shaped both the economy and everyday life in Ōsawa, the mountainous terrain imposes significant disadvantages compared to lowland regions. Facing prolonged declines in tea prices, and labor shortages, the community—led by the TIRA—began seeking new ways to sustain their traditional livelihoods.

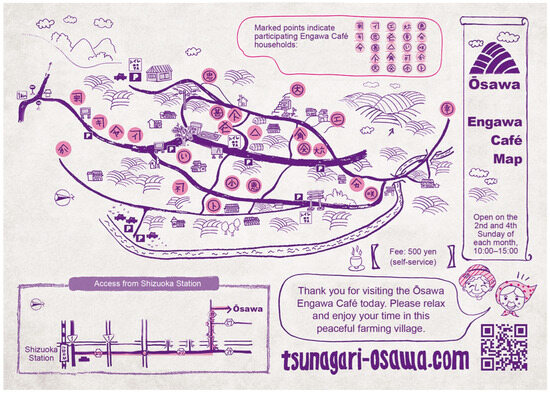

One such initiative was the Engawa Café: a community-led project launched as part of broader revitalization efforts. Operated by individual households on a voluntary basis, the café adopts unified pricing and shared management to minimize operational burdens. It makes use of local resources such as traditional homes, tea fields, and home-processed tea. On café days, visitors are welcomed into the village to enjoy tea, handmade refreshments, and casual conversation in a relaxed rural setting (Table 2, Figure 5). While modest in scale, the Engawa Café illustrates how small mountain communities can reframe their traditions as living resources—fostering both social cohesion and a renewed sense of purpose among residents.

Table 2.

Operational overview of the Engawa Café project.

Figure 5.

Visitor map of the Ōsawa Engawa Café. Source: adapted with permission from Ref. [61]. 2023, Ōsawa Promotion Association.

3.2. Study Design

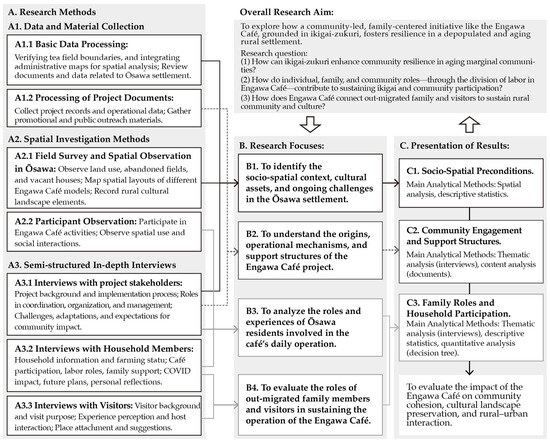

To examine how the Engawa Café project fosters rural revitalization in the context of a depopulated and aging rural settlement, this study adopts a qualitative, locally grounded design combining seven interrelated methods across three categories (Figure 6). First, to understand the socio-spatial context and local cultural assets, we conducted: basic data processing, field surveys and spatial observation, and stakeholder interviews regarding the background of the Ōsawa settlement. Second, to investigate the origins and operational structure of the Engawa Café project, we analyzed: project documents and outreach materials, and conducted stakeholder interviews focused on coordination and support mechanisms. Third, to analyze resident roles and everyday experiences, we used: participant observation during café operations, in-depth interviews with household members, and follow-up stakeholder interviews. Fourth, to evaluate the contribution of out-migrated family members and visitors, we conducted: in-depth interviews with household members regarding family roles, and visitor interviews capturing motivations, engagement, and perceived impact.

Figure 6.

Research workflow and methodological framework. Note: Different arrow styles are used solely for visual clarity and do not indicate different types of relationships.

Interviews were conducted with a total of 26 individuals, including local residents, project stakeholders, and visitors (Table 3 and Table 4). All participants provided informed consent prior to data collection. As shown in Table 3, ten of Ōsawa’s 22 households were interviewed directly, while information for the remaining twelve was obtained through proxy interviews conducted by the Ōsawa representative. This individual, a long-standing community leader, was closely familiar with all households and conducted follow-up visits to validate and supplement the reported information. Two project stakeholders and seven visitors were also interviewed (Table 4). Household IDs and participant numbers are retained throughout the analysis to ensure consistency in qualitative citations.

Table 3.

Profile of Ōsawa households and interview participation.

Table 4.

Profile of interviewed project managers and visitors.

To enhance the quality and credibility of the qualitative analysis, triangulation was used across methods and respondent types to cross-check key themes (Figure 6). Data saturation was considered reached when no new codes appeared in later interviews. Based on this empirical foundation, we conducted a structured thematic analysis to identify participation patterns and underlying mechanisms. The Engawa Café initiative was examined from three interrelated perspectives: spatial, communal, and familial (Figure 6).

At the socio-spatial level, we examined the preconditions of the Ōsawa settlement, including its social structure, land-use patterns, local cultural assets, and the multifunctional use of engawa spaces. At the community level, we examined the role of local leadership, informal rules, mutual support systems, and the organizational structures that facilitated collective action. At the household level, we focused on family composition, gender roles, internal cooperation, and the involvement of out-migrated family members who returned to assist in café operations. These individuals, along with repeat visitors, played a pivotal role in enabling certain households to continue participation, highlighting the importance of inter-household and intergenerational ties in sustaining community-based initiatives. This multi-layered framework provided a comprehensive interpretive basis for identifying participation patterns and informed the subsequent quantitative validation using CHAID analysis.

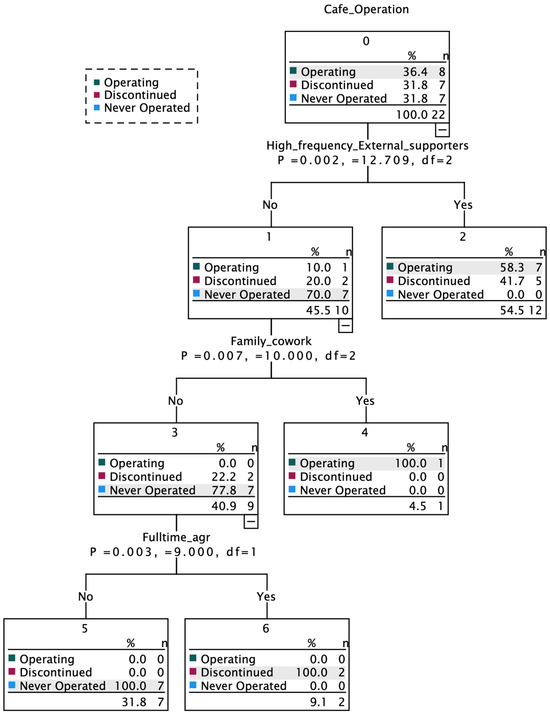

Based on these qualitative insights, a Chi-square Automatic Interaction Detection (CHAID) decision tree analysis was subsequently conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0.1 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) [62]. This method is well-suited for categorical variables and is commonly used to identify statistically significant hierarchical relationships among multiple predictors [63,64]. The dependent variable was café operational status (Operating, Discontinued, or Never Operated), while all independent variables were binary (more details on this in later sections).

The analysis was based on a total sample of n = 22 households. To enhance the robustness and generalizability of the model, a five-fold cross-validation procedure was applied. The maximum tree depth was set to automatic (up to three levels for CHAID). The minimum number of cases required for parent and child nodes was set to 4 and 1, respectively. The significance level for node splitting and category merging was set at p < 0.01, with Bonferroni adjustment, to mitigate overfitting risks associated with the small sample size [64]. Pearson’s chi-square test was employed as the splitting criterion. This quantitative analysis was conducted primarily to validate and support the qualitative findings, providing additional insights into the household-level determinants of café operational status.

By interpreting this case within the broader field of Japanese rural revitalization, our analysis highlights how bottom-up, culturally rooted approaches such as ikigai-zukuri models like the Engawa Café can enhance community cohesion, cultural landscape preservation, and rural–urban interaction, and can inform more context-responsive policy design and adaptive development frameworks.

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Spatial Preconditions for the Engawa Café Project

4.1.1. Demographic Changes and Agricultural Resilience in Ōsawa

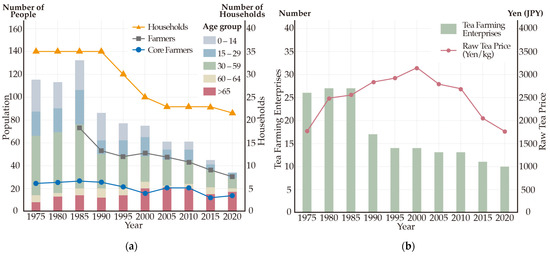

The demographic and agricultural data presented in this section are primarily based on official statistics compiled by the Shizuoka City Office and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) [58]. Additional information—particularly the longitudinal changes in the number of households and the most recent demographic and agricultural data (as of around 2025)—was supplemented through interviews with the Ōsawa representative (A2).

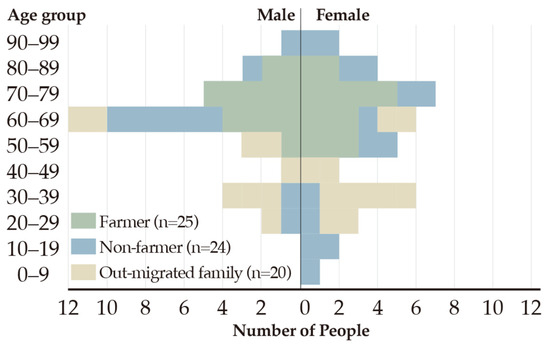

A key characteristic of Ōsawa’s population dynamics is the shift from social attrition (primarily out-migration) during the 1990s–2000s to an increasing impact from a natural decrease after 2010. This period (1990s–2000s) saw a sharp decline in the number of households, which subsequently stabilized (Figure 7a). Structurally, by 2020, the elderly population constituted over half of the total, while the youngest cohort (0–14 years) represented less than 10% (Figure 7a). According to interviews with the Ōsawa representative (A2) regarding the situation circa 2025, agriculture is primarily undertaken by the middle-aged and older population, as nearly all residents under 50 have migrated out, leading to a critical lack of agricultural successors (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Demographic and agricultural trends in Ōsawa (1975–2020). (a) Population trends showing age group distribution, total farmers, core farmers, and number of households; (b) trends in the number of tea farming enterprises and the raw tea price (JPY/kg). Note: data pertaining to households and farming enterprises from 1975 to 1985 include both subsistence and commercial farm households, whereas data from 1990 onwards solely represent commercial farm households [58]. Household number data were obtained through an interview with the Ōsawa representative (A2).

Figure 8.

Demographic structure of Ōsawa by age group, sex, and status (farmer, non-farmer, out-migrated family) as of approximately 2025. Data source: interview with the Ōsawa representative (A2).

As shown in Figure 7, while out-migration has contributed to a decrease in tea farming enterprises (Figure 7b), the core agricultural workforce has remained relatively stable over recent decades (Figure 7a), enabling Ōsawa to maintain a high cultivation rate. However, the continuous decline in raw tea prices (Figure 7b) has severely impacted farmers’ incomes. As a result, Ōsawa tea farmers have adapted cultivation practices to reduce labor and costs, shifting from three annual harvests to just one while also minimizing or ceasing the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Furthermore, compared with other crops, tea cultivation suffers less from bird and animal damage and does not require frequent crop rotation [65]. This reduced agricultural demand allows Ōsawa’s tea farmers more time and energy for part-time work or other activities, such as the Engawa Café.

Notably, over half of the residents aged 80–89 continue to engage in agriculture (Figure 8). This aligns with Japan’s world-leading life expectancy [66] and findings that farmers often experience greater longevity than non-farmers [67]. This suggests that although Ōsawa’s current agricultural production relies heavily on farmers aged 60 and over, they may sustain these activities for another 10 to 20 years.

4.1.2. Spatial Characteristics and Landscape Dynamics in Ōsawa

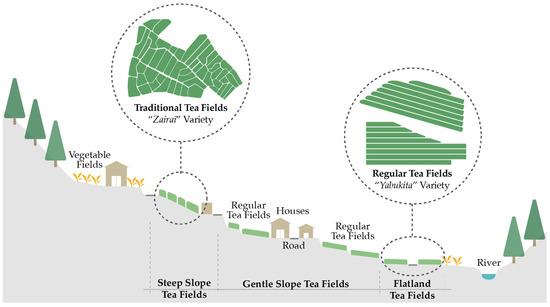

As illustrated in Figure 9, Ōsawa settlement follows a linear pattern along the river valley, integrating residential dwellings, tea fields, and private tea factories. Tea cultivation dominates the agricultural landscape, characterized by small, dispersed fields on sloped terrain. Alongside fields of improved varieties like Yabukita, Ōsawa maintains traditional fields of native varieties (Zairai). These Zairai tea (native variety) fields, often exhibiting irregular, curvilinear patterns (Figure 10) suited to historical manual harvesting, persist despite their low market value (fetching only about 40% of Yabukita’s price) and representing less than 1% of Shizuoka’s tea cultivation area [68]. Their preservation in Ōsawa (Figure 10) is largely confined to steep slopes where conversion to Yabukita (which thrives on more favorable land) is impractical. Nevertheless, these Zairai tea fields, with their deep roots, disease resistance, and longevity (often over 100 years), offer ecological benefits such as soil retention and biodiversity support [69], serving as vital symbols of Ōsawa’s cultural landscape. Beyond its landscape and ecological significance, Zairai tea has also emerged as a signature offering of the Engawa Café, allowing visitors to directly engage with a product deeply rooted in local tradition.

Figure 9.

Land use distribution in Ōsawa (observed 2025). Data source: fieldwork observations and interview with the Ōsawa representative (A2). See Figure 10 for a schematic cross-section along line A–A′.

Figure 10.

Schematic cross-section along line A–A′ in Figure 9, illustrating topography and land use patterns in Ōsawa. Data source: fieldwork observations and interview with the Ōsawa representative (A2).

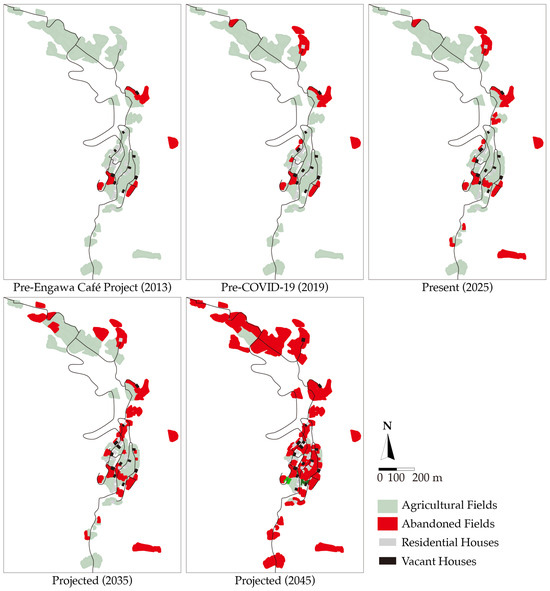

However, reflecting the decline of the tea industry and depopulation, Ōsawa also faces spatial degradation challenges, including abandoned tea fields and an increasing number of vacant houses (Figure 9). Land abandonment has become particularly evident in peripheral areas over the past decade (Figure 11). Even the launch of the Engawa Café has not been sufficient to halt this structural decline, which is primarily driven by aging and the lack of successors. Nevertheless, aided by the long-standing community custom of mutual support (sōgo-fujo) and further motivated by the Engawa Café project, residents actively manage vacant spaces, supplementing regular collective settlement cleaning activities. Some residents who have ceased farming even entrust their tea fields to others for cultivation, receiving a portion of the harvested tea as compensation, demonstrating a non-monetary, trust-based mutual support mechanism (Figure 9).

Figure 11.

Evolution of land abandonment and housing vacancy in Ōsawa: past trends, present status, and future projections (2013–2045). Data source: interview with the Ōsawa representative (A2); compiled by the author.

Beyond these practical efforts, the Engawa Café has also contributed indirectly to landscape conservation by reinforcing the cultural and symbolic value of local spaces. Although residents did not explicitly associate the Engawa Café with landscape conservation, Ōsawa has maintained a comparatively high rate of tea cultivation (Section 3.1.1), particularly of the traditional Zairai variety, relative to neighboring settlements. Through visitors’ interest and appreciation for Ōsawa’s landscape, the project has reinforced residents’ recognition of its value. This, in turn, has indirectly encouraged conservation efforts and helped mitigate rural landscape degradation.

While these mutual support practices effectively mitigate landscape degradation and contribute to spatial and cultural continuity, the temporal comparison of land use changes (Figure 11) also indicates that community internal efforts alone may struggle to fundamentally address the structural risks posed by advancing aging and depopulation. Land and housing abandonment is projected to accelerate sharply over the next two decades—posing not only a risk of agricultural collapse but also a deeper threat to the continuity of the community itself.

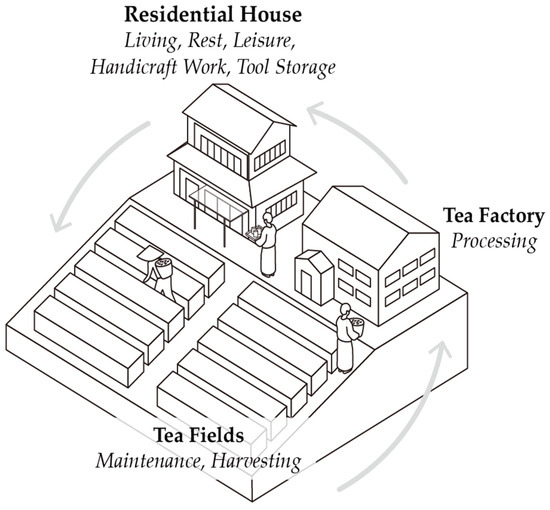

4.1.3. Livelihood, Lifestyle, and the Continuing Landscape

Ōsawa’s livelihood pattern, centered on tea cultivation, reflects a traditional lifestyle in which work, family, and place are deeply interwoven, forming a distinctive cultural landscape [70]. Although declining profitability in the tea industry has led many farmers to shift to part-time farming, the traditional, family-centered practice of self-cultivation and processing remains widespread (Figure 12). During harvest season, tea farmers collaborate with family members—including out-migrated relatives—reinforcing both livelihoods and intergenerational ties. Their ongoing commitment to traditional farming reflects not only a pursuit of quality but also supports the persistence of the traditional Zairai variety. Despite its bitterness and lower market value, Zairai tea is refined through local processing techniques to bring out its unique qualities. These enduring practices embody intergenerational memory, technical knowledge, and a strong sense of place [71], showing how cultural identity and place attachment continue to shape livelihood choices.

Figure 12.

Schematic representation of the traditional “Self-cultivation and Processing” cycle in Ōsawa’s tea farming households (during harvest season). Data source: interview with the Ōsawa representative (A2); compiled by the author.

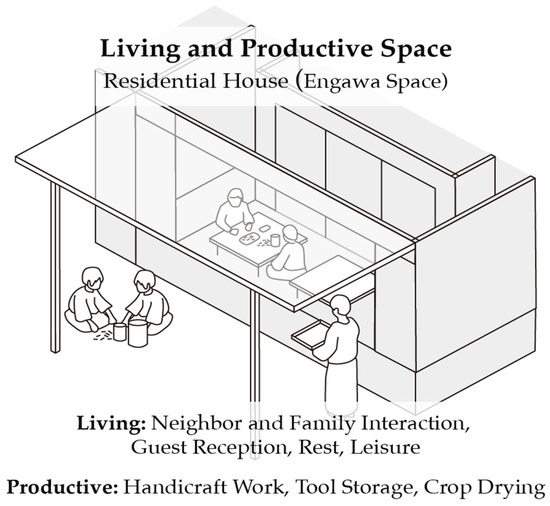

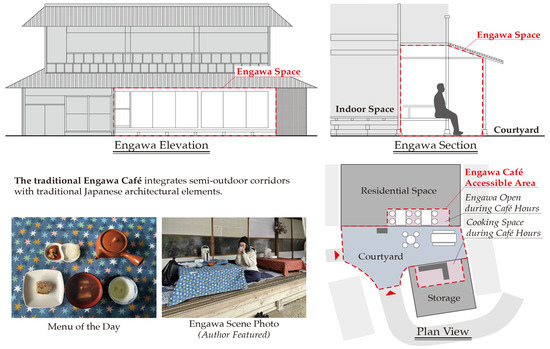

This enduring attachment to tradition also manifests in everyday spatial practices—particularly through the use of the engawa. As a transitional space in traditional Japanese dwellings, the engawa historically served multiple functions, including neighborhood interaction, crop processing, and tool storage [72,73]. While this architectural feature has largely disappeared in modern housing [74], it remains integral in Ōsawa to daily life and work, especially in farming households where it is still commonly used to host guests—reflecting the local spirit of omotenashi (hospitality) (Figure 13). Despite economic and demographic decline, Ōsawa residents continue to uphold cultural practices—a commitment rooted in strong place attachment and cultural identity. Studies suggest that higher place attachment is associated with stronger ikigai [75]. In this light, their efforts to preserve traditional livelihoods and spatial routines can be seen as an active pursuit of ikigai.

Figure 13.

Multifunctional role of the engawa space as a living and productive area in traditional Ōsawa households. Data source: interview with the Ōsawa representative (A2); compiled by the author.

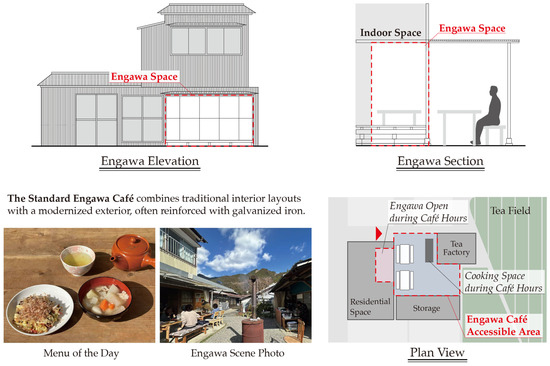

4.1.4. Spatial Reinterpretation and Cultural Continuity: Three Forms of the Engawa Café

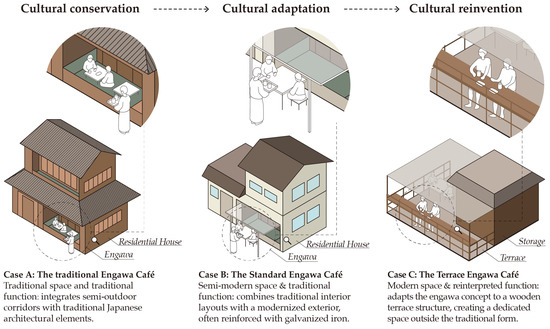

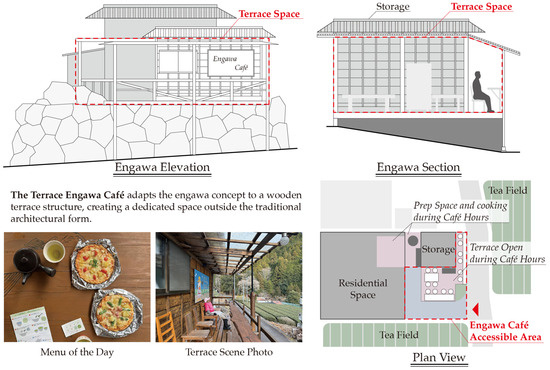

Through the Engawa Café initiative, residents welcome visitors into their engawa, not only sharing their everyday lives in an authentic setting, but also actively sustaining the traditional functions of this spatial element by transforming what was once a private space into a semi-public one. To examine how spatial form intersects with cultural practice in the Engawa Café project, we compare three distinct configurations (Figure 14), each representing a different configuration of architectural structure and cultural continuity:

Figure 14.

Typology of Engawa Café configurations: three models of Engawa Café implementation in Ōsawa. Data source: fieldwork observations; compiled by the author. See Appendix A, Figure A1, Figure A2 and Figure A3 for detailed statements.

Case A: The first café preserves both traditional architecture and the engawa function. Operated by a multigenerational tea-farming household, the grandmother welcomes visitors with handmade seasonal snacks, offering an intimate look into rural domestic life. As one guest reflected, “It made me feel like returning to childhood” (C4). In this case, the engawa acts as a spatial catalyst that evokes memory and emotion, enhancing place attachment and visitor satisfaction [76,77].

Case B: This café adopts a modernized exterior while retaining traditional interior layouts and cultivating Zairai tea. Visitors are invited to engage in activities such as comparative tea tasting and wood chopping. One participant noted, “Seeing the fire burn with the wood I split gave me a real sense of accomplishment” (C2). These embodied, participatory experiences foster affective engagement and help renew both personal and collective ties to rural culture [78,79].

Case C: Operated by a non-farming family, this café recreates the engawa experience using a wooden terrace and pizza oven originally built for their children. Tea is sourced from former family-owned fields now cultivated by neighbors. “Even if it’s not a traditional engawa, it still connects us with others,” one resident explained. The experience offers visitors a creative reinterpretation of rural hospitality.

While Case A represents a costly preservation of cultural form, Cases B and C show more flexible adaptations to contemporary material conditions. In all cases, however, the cultural logic of the engawa is preserved—demonstrating strong functional and symbolic continuity. As Hall (1932) argues, identity does not depend on unbroken spatial or temporal presence [80]. Traditions can retain symbolic meaning even amid material change. This café thus represents not a rupture, but a reinterpretation, where continuity is maintained through emotional and cognitive ties rather than physical replication [80].

4.2. Structural Foundations and Ikigai-Driven Logic Behind the Engawa Café Project

4.2.1. Multi-Actor Coordination and Implementation Mechanism

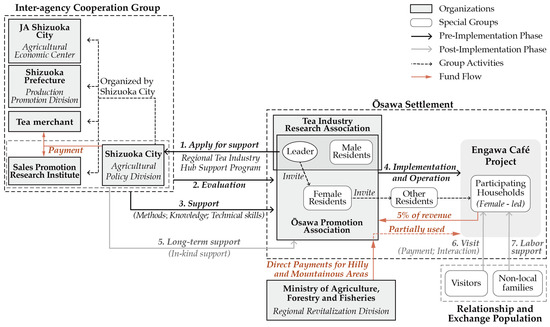

Figure 15, based on interviews with the Ōsawa representative (A2) and a Shizuoka City official (A1), illustrates how the Engawa Café project emerged not through top-down planning, but through continuous dialogue and adaptive coordination across institutional, expert, and community actors. It began when the Ōsawa representative (A2) applied for support under Shizuoka City’s Regional Tea Industry Hub Support Program (Step 1). Following evaluation, the proposal was approved (Step 2), and a multi-agency platform was formed, involving five stakeholders: city officials, the prefectural agricultural office, JA Shizuoka, a tea merchant, and an advertising consultant. These actors held biweekly meetings with the Ōsawa representative (A2) and the TIRA (Step 3), while the Ōsawa representative (A2) relayed discussions to all households through monthly meetings, ensuring transparency and community-wide involvement.

Figure 15.

Implementation and funding mechanism of the Engawa Café Project. Data source: interviews with the Ōsawa representative (A2) and the Shizuoka City Government Official (A1); compiled by the author.

Among the early proposals, residents suggested upgrading tea processing equipment, but this proved financially unviable. Meanwhile, the city’s recommendation to sell directly at farmers’ markets was declined due to residents’ limited marketing experience. At this turning point, the local tea merchant—well-acquainted with Ōsawa’s daily life and social culture—proposed a hospitality-centered model tailored to local conditions. Drawing on the community’s spirit of omotenashi (hospitality) and the multifunctionality of engawa, the Engawa Café concept was born and gained unanimous support at the monthly meeting (Step 4).

While strong local leadership was vital [81], resident cooperation was equally crucial [82]. In Ōsawa, high participation stemmed not only from traditional mutual support but also from residents’ deep attachment to their way of life—the key source of ikigai. This attachment motivated them to actively engage in local revitalization efforts and participate in collective decision-making.

The Ōsawa representative (A2) played a key intermediary role, while the tea merchant, drawing on local knowledge, proposed a culturally resonant model that encouraged residents to stay engaged in meaningful and familiar practices. External actors (ICG) provided technical and business support, helping to reduce risk and build confidence.

Together, these structural and motivational foundations—anchored in ikigai—enabled the successful implementation of the Engawa Café project as both a cultural revitalization effort and a sustainable community practice.

4.2.2. Women’s Participation and the Everyday Practice of Ikigai

Given that café operations center on food preparation, a task traditionally undertaken by women in most households [83,84], female participation was essential for the project’s viability. To facilitate this, the community established the Ōsawa Promotion Association (OPA), by inviting female leaders to join the previously male-led TIRA (Figure 15, Step 4). Female residents became the main implementers of the Engawa Café.

In rural Japan, women’s roles centered on domestic duties and supporting farm labor [85,86], often limiting their engagement in formal economic activities and community decision-making [87]. While national policies increasingly advocate for women‘s “social participation”, their potential and willingness often remain overlooked or unsupported in many rural communities [86].

The Engawa Café provided an opportunity that fit with women’s existing routines and skills, especially in cooking and hospitality. To support flexible involvement, OPA allowed each household to decide whether and when to participate, rather than requiring fixed schedules. This structure reduced pressure and made it easier for women to take part.

Through involvement in OPA meetings and coordination tasks, female residents gained greater visibility in community affairs. More importantly, their engagement—centered on food sharing, and neighborly exchange—reflected a form of participation deeply tied to their sense of ikigai [28]. The Engawa Café thus served not only as a tool for local revitalization but also as a meaningful space where women could contribute in ways that reinforced purpose, belonging, and continuity.

4.2.3. Sustaining the Engawa Café: A Multi-Source Support Framework

The Engawa Café project’s viability hinges on its multi-source financial framework. While Shizuoka City provided initial start-up funding of approximately JPY 1,000,000 via the “Regional Tea Industry Hub Support Program” for essential early-stage costs like consulting and basic infrastructure (Figure 15, step 3), this municipal subsidy alone was not sufficient.

The successful launch and continued operation of the project have relied heavily on an annual subsidy of approximately JPY 800,000. This support is provided by the MAFF through the “Direct Payments for Hilly and Mountainous Areas” program. Although originally intended to sustain agricultural activities in disadvantaged regions, the subsidy has been flexibly used to support rural revitalization efforts such as the Engawa Café project [88]. However, eligibility for this subsidy depends on the continued use of farmland. If land abandonment in Ōsawa persists, the payments may be gradually reduced or even terminated, posing a direct threat to the café’s long-term sustainability.

Additionally, participating households contribute 5% of their café revenue to the OPA to support the maintenance of communal facilities and the ongoing operation of the Engawa Café.

To complement public support, participating households contribute 5% of café earnings to the OPA to maintain communal facilities and café operations (Figure 15, Step 5). Support has also come from non-resident family members, who directly assist in operations, and from visitors, who contribute financially and emotionally through their presence (Figure 15, Steps 6–7). These combined forms of engagement foster a new type of relationship-based support that blends economic input with social solidarity—laying a hybrid foundation for long-term sustainability.

4.3. Evolving Participation and Support Structures of the Engawa Café

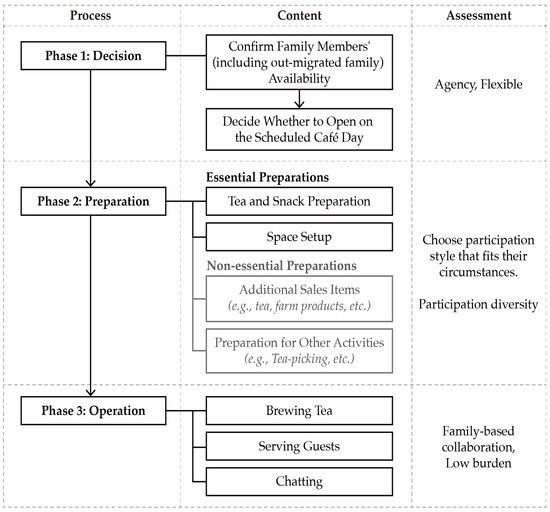

4.3.1. Flexibility in Participation: Household-Specific Operational Models

The Engawa Café project operates on a highly autonomous model, allowing each household to tailor its participation according to family availability, resources, and preferences (Figure 16). Decisions on whether to open on scheduled café days, what menu items or services to provide (e.g., tea-picking, farm experiences), whether to offer additional sales goods (e.g., tea or produce), and how to arrange the engawa space are all left to individual households. This highly flexible and low-burden approach has been widely accepted, fostering diverse participation styles and ensuring continuity.

Figure 16.

Household decision-making and operational flow in the Engawa Café project. Data source: interviews with local residents; compiled by the author.

4.3.2. From Economic Motives to Ikigai Realization: The Deepening Dynamics of Residents

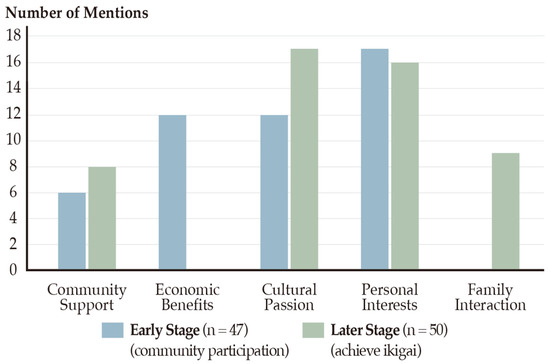

As shown in Figure 17, initial participation in the Engawa Café project was primarily motivated by the hope of promoting tea and boosting sales, a goal aligned with the project’s original aim of revitalizing the tea industry (See Appendix A, Table A1 for detailed statements). However, interest in cooking and chatting served as an essential prerequisite for participation; without such enjoyment, residents noted they would not have chosen to get involved. Over time, however, their motivations shifted toward non-economic goals such as cultural transmission, urban–rural exchange, family reconnection, and personal enjoyment. Interviews revealed frequent references to ikigai, reflecting a strong desire among residents for self-worth and recognition.

Figure 17.

Frequency of mentioned motivations for Engawa Café participation: early vs. later stages. Note: Frequencies represent the number of distinct instances where each motivation was semantically identified and coded from participant interview transcripts. Each distinct semantic expression of a motivation was counted once, even if discussed extensively. The early stage analysis is based on data from 15 households, and the later stage analysis is based on data from 8 households. See Appendix A, Table A1 for detailed statements and household IDs.

For many in Ōsawa, agricultural work itself already constitutes a form of ikigai. As one resident (ID. 8) shared, “Every time before going to the tea fields, I say ‘Let’s have a great day together’ and thank them when I’m done”. Yet, with the ongoing decline of the tea industry and population loss, affirmation from visitors has become a vital source of encouragement for maintaining this sense of purpose. The Engawa Café has not only brought out-migrated family members back more frequently but has also strengthened intra-family bonds and provided residents with meaningful roles to express their skills and contribute to others, reinforcing both personal value and collective cohesion.

Consistent with national trends reported by the Japanese Cabinet Office, older adults primarily derive ikigai from “family connections” (44.1%), “hobbies and leisure” (33.5%), and “engagement in work” (31.8%), with economic income ranking lowest (6.5%) [89]. This study similarly finds that emotional fulfillment, social recognition, and intergenerational ties are key drivers of continued participation in the Café project.

4.3.3. Factors Influencing Engawa Café Operational Status: A Household-Level Analysis

As shown in Table 5, although 15 households have participated in the Engawa Café, only eight remain active, revealing structural barriers to long-term sustainability.

Table 5.

Distribution of key household characteristics by Engawa Café operational status.

Among the seven households that never operated, five are male-only. Due to the gendered division of food preparation and their focus on external careers, these residents tend to derive ikigai from personal work rather than family or community engagement.

The seven households that discontinued operations mainly did so due to the illness or passing of elderly women who led the café. While younger women were present, they often faced time constraints from work or childcare. Still, many expressed hopes of resuming post-retirement. As noted by residents (ID. 5, 7) said: “Once I have time, I’d like to reopen the Café”. Female-led efforts without family support also proved unsustainable, as in ID. 7 and 12.

In contrast, the currently operating households generally demonstrate a pattern of intra-family collaboration. Most also receive regular support from out-migrated relatives, who primarily assist with guest reception, while a few contribute remotely through packaging design or social media promotion (ID. 2, 8), thereby strengthening family ties.

Although women play a central role in operating the Engawa Café, long-term continuity requires sustained support from other family members.

4.3.4. Post-Pandemic Visitor Shifts: Deepening Bonds and the Rise of the Related Population

As shown in Table 6, the Engawa Café attracted an average of 5728 annual visitors before COVID-19, primarily from Shizuoka City (63%). Most were aged 50–69, a demographic generally characterized by economic stability [90] and a strong interest in rural cultural and landscape experiences [91]. Notably, 44% were repeat visitors, suggesting high levels of satisfaction and place attachment.

Table 6.

Comparison of Engawa Café operations Pre- and Post-COVID-19.

Since the pandemic, annual visitor numbers dropped to 1251 (2024), and per-session income was reduced by more than half. While residents acknowledged the impact of fewer guests and lower earnings, they also reported deeper engagement with visitors, including more meaningful conversations and occasional participation in farming activities (ID. 2, 6, 8, 10, 14, 21). Repeat visitors became the primary customer base, motivating many households to continue café operations (ID. 6, 8, 10, 14, 21). Several visitors described the deep attachment they developed to the café and the community:

“I felt lonely during the pandemic, so I came back as soon as the Café reopened. I visit almost every time.”(C1)

“We’ve become good friends. I even invited them to visit my home.”(C7)

“I bring tea that I personally enjoy sharing with the residents.”(C8)

“The air, the landscape, the food, and the people here make me feel truly relaxed.”(C3)

Despite a three-year suspension and decreased revenue, household livelihoods remained stable due to diversified income sources such as tea cultivation and off-farm employment. Ōsawa’s longstanding tea culture not only underpins the Café’s continued appeal but also enhances its resilience to external shocks.

The concepts of exchange population (kōryū jinkō) [92] and related population (kankei jinkō) [93] are key to rural studies in Japan. The former refers to short-term visitors with minimal ties, while the latter includes non-residents who maintain ongoing connections with a locality [94]. Unlike typical tourism-based models, the Engawa Café operates through close, in-home interactions. This structure creates conditions that support the transition from communication to related population [95]. In the post-pandemic period, repeat visitors have become the primary customer base, forming stable, trust-based relationships with local residents.

By fostering place attachment and embedding non-residents into local social networks, related populations can supplement community functions and support rural revitalization beyond short-term economic approaches [95,96].

4.3.5. External Support and Family Collaboration: Key Determinants of Café Continuity

Building on previous analyses, this section examines how external family support, intra-family collaboration, and engagement in tea farming influence the operational status of Engawa Cafés. While interviews (Section 4.2.2 and Section 4.3.3) emphasized the importance of senior female participation and household cooperation, the roles of external support and agricultural involvement remain less clearly understood.

To quantitatively assess the effects of these factors, a dataset consisting of nine categorical variables across four dimensions was constructed based on interview data (Table 7). To reduce the risk of overfitting due to the small sample size, a conservative significance threshold of p < 0.01 was applied [64].

Table 7.

Structure of variables used in decision tree analysis.

Although the re-substitution error was acceptable (0.227), the higher cross-validation risk (0.409) suggests limited generalizability (Table 8). Accordingly, the results should be interpreted within the scope of this study.

Table 8.

Model risk estimates from CHAID decision tree analysis.

The model correctly classified 77.3% of households overall, with high accuracy for “Operating” and “Never Operated” households (Table 9). “Discontinued” cases were harder to predict due to their reliance on health-related factors, which were excluded from the model to avoid overfitting.

Table 9.

Classification matrix for household café operation status predicted by CHAID model.

The results of the CHAID analysis (Figure 18) show that the most significant predictor was high-frequency external family support (χ2 = 12.709, p = 0.002, df = 2). Among the 12 households with such support, seven (58.3%) maintained café operations. Although external supporters typically assist only with simple tasks, their involvement likely facilitates intergenerational interaction, fulfilling elderly residents’ ikigai-related need for family connection [89]. In this sense, café activities serve as a vehicle for sustaining family bonds.

Figure 18.

CHAID decision tree.

Second, among households lacking external support, internal family cooperation emerged as the next key factor (χ2 = 10.000, p = 0.007, df = 2). In families without active internal collaboration, particularly those composed solely of elderly males (see Section 4.3.3), café operation was never initiated. The remaining households, ID. 7 and 18, had operated previously but discontinued following the death of the lead member, with no one available to take over. This supports residents’ comments: “If no one helps, it’s hard to keep going” (ID. 2, 6, 10, 14, 21).

Finally, in the absence of both external and internal support, the presence of full-time farmers emerged as the determining factor (χ2 = 9.000, p = 0.003, df = 1). Households ID. 7 and 18 continued tea farming even after discontinuing café operations, underscoring agriculture as their core livelihood. In contrast, households that never operated a café (e.g., ID. 1, 11, 16, 20, 22) were mostly engaged in off-farm employment, suggesting that their primary focus may have already shifted away from the village.

All household participation provided a robust foundation for the decision tree analysis. The results clearly demonstrate that the long-term viability of the Engawa Café project depends not solely on labor or agricultural resources but more fundamentally on the presence of external family support and intra-household collaboration. Without both, residents continue tea farming as their primary livelihood, and agriculture is still their core occupational identity. While the café may enhance farmers’ social identity, it does not alter the agricultural basis of that identity [97].

5. Discussion

This study conducted a detailed analysis of the socio-spatial dynamics, formation, and community participation of the Engawa Café in Ōsawa. The findings reveal not only the underlying logic of rural livelihoods in marginal settlements but also how a small, locally grounded initiative can enhance community resilience.

The following discussion examines this case through the lens of ikigai-zukuri, focusing on community capacity, external catalysts, and cultural landscape assets. It highlights how local resources—without large-scale infrastructure or economic investment—can foster aging in place, intergenerational ties, and rural revitalization.

5.1. The Underlying Logic of Rural Livelihoods: A Case Study of the Ōsawa Marginal Settlement

Ōsawa’s agricultural livelihood, closely tied to residents’ cultural identity, reflects the role of farming as both an economic activity and a source of spiritual and cultural fulfillment. Despite its declining profitability, farming remains a point of pride for many residents, evident in their continued cultivation of low-market-value Zairai tea (Section 4.1.2) and expressed reverence for agricultural work (Section 4.3.2). Studies show that even when no longer economically central, farming continues to symbolize social status and life meaning in rural communities [97,98].

Ōsawa’s communal solidarity and tradition of mutual support underpin the persistence of this marginal settlement [59]. Residents not only engage in altruistic, self-initiated efforts to maintain the settlement’s landscape (Section 4.1.2) but also collaborate within families to operate the Engawa Café. These operations frequently involve out-migrated family members, demonstrating a broader pattern of intergenerational engagement. Collectively, these dynamics reflect the strong community cohesion and familial support that characterize rural Japanese society [25].

While aging poses severe challenges for marginal settlements, particularly in terms of isolation from broader society, the proactive pursuit of ikigai among older residents emerges as a potential driver of rural revitalization. Ōsawa faces acute demographic decline (Section 4.1.1); however, rather than passively accepting social disconnection, many senior residents actively seek renewed interaction and recognition through participation in the Engawa Café project. By engaging in meaningful labor and maintaining connections with visitors and family members, they strive to sustain their sense of ikigai.

Rooted in long-standing tea cultivation, Ōsawa’s local culture has shaped both its landscape and residents’ daily practices, reinforcing a stable sense of identity and belonging. For rural residents, the village is not only a place of residence but also a site of inherited traditions. This close connection between people and land has supported the continuity of the community despite demographic and economic decline. The case of Ōsawa illustrates how localized cultural practices can contribute to the persistence of marginal settlements under structural pressures.

5.2. Defining Ikigai-Zukuri (Enhancing Life Purpose) and Its Significance

Findings from the Engawa Café project suggest that ikigai-zukuri can be an effective strategy for revitalizing marginal settlements and promoting “aging in place” among rural older adults.

Unlike mainstream policies that focus on urban-centered, welfare-oriented activities such as hobby classes and sports events [25,26], our findings highlight the importance of work-like, family-based, and locally rooted participation as key sources of ikigai, particularly in rural contexts. Aging in rural areas is often accompanied by shrinking social roles, isolation, and limited access to services. However, as seen in the Ōsawa case, older residents are active contributors to the local community. Their roles include hosting visitors, maintaining traditional production-based lifestyles, and coordinating with out-migrated family members to sustain the Engawa Café initiative. These forms of everyday engagement reaffirm their social value and reinforce a sense of purpose. In this context, aging is not an endpoint but a phase of active redefinition.

Given ikigai’s link to lower mortality and better mental health [99,100], ikigai-zukuri initiatives like the Engawa Café provide older adults with opportunities to reclaim agency, maintain both physical and emotional vitality, and remain socially connected. Since many older people prefer to remain in their lifelong communities, even in marginal settlements [101], such locally embedded initiatives are increasingly vital. Ikigai-zukuri can strengthen personal well-being while enhancing rural resilience, thereby supporting sustainable aging in place [3].

Based on our analysis of the Ōsawa case, this study defines ikigai-zukuri as follows:

“A locally grounded approach that provides sustainable, low-burden, family-based opportunities for work or social participation (Section 4.2) [102,103], encouraging the return of out-migrated family members (Section 4.3.2 and Section 4.3.5) [104] and enabling older residents to lead fulfilling lives in familiar surroundings (Section 4.1.3)”.

5.3. Repositioning Roles for Rural Continuity: Insights from Ōsawa’s Six Actors Framework

The sustainability of marginal settlements like Ōsawa depends not on a single actor but on the coordinated efforts of six key actors: residents, related population, exchange population, local leaders, embedded experts (such as tea merchants), and public institutions, including local and national governments. This framework, derived from the stakeholder analysis presented in Table 10, highlights the multifaceted nature of community revitalization. What emerges is not just a collective effort but a community-based revitalization framework grounded in ikigai-zukuri, where clearly differentiated roles contribute to rural resilience and long-term sustainability.

Table 10.

Key roles and responsibilities in the Ōsawa marginal settlement.

5.3.1. Local Participation as the Foundation of Ikigai-Zukuri

Ikigai-zukuri projects must begin with local actors. In Ōsawa, older residents were not passive recipients of support but active agents capable of initiating and sustaining engagement. Their participation in community-run initiatives like the Engawa Café allowed them to express agency, pass down knowledge, and reframe their roles within the social fabric (Section 4.3.2). These practices, rooted in everyday life, form the core of ikigai-zukuri.

The local leader played a pivotal role in facilitating this process. His strengths included not only deep local knowledge, personal credibility, and social connectivity but also the ability to identify residents’ real needs and mediate effectively between external actors (such as tea merchants and municipal staff) and the community (Section 4.2.1).

5.3.2. External Relations: Building Emotional and Functional Linkages

In ikigai-zukuri, external populations contribute not only practical assistance but also essential emotional support. Out-migrated family members, as part of the relationship population, play a crucial role in supplementing local labor, strengthening familial bonds, and maintaining intergenerational ties. Although they are not permanent residents, many return regularly during key community events (Section 4.3.2 and Section 4.3.5). Their primary motivation is to support family activities, with leisure playing a secondary role [105]. These recurring visits constitute a form of soft capital, flexible, emotionally grounded, and more adaptable to local realities than rigid, resettlement-focused policies. Moreover, the recognition and encouragement they offer help reaffirm residents’ sense of ikigai [106].

Exchange populations, such as short-term visitors, often form close interpersonal connections with residents during their stay. The immediate positive feedback they provide boosts residents’ confidence and reinforces their sense of ikigai (Section 4.3.2). Through repeated and meaningful interactions, some of these visitors gradually evolve into relationship population members, developing lasting ties with the community.

Together, relationship and exchange populations form a reciprocal loop that sustains ikigai-zukuri: emotional affirmation and social recognition from outsiders enhance residents’ motivation, while residents’ authenticity and hospitality deepen visitors’ attachment to the place. This mutual reinforcement contributes not only to individual well-being but also to the long-term social cohesion and revitalization of marginal settlements like Ōsawa. However, these interactions remain contingent on the continued presence of local actors. As aging progresses without generational succession, the disappearance of elder residents could disrupt these relational networks entirely. Therefore, these connections should not be viewed as stable assets, but as fragile and relational dynamics that require sustained support.

5.3.3. Deepening Exchange: From Communication to Relationship Population

A particularly important implication lies in the evolving relationship between the communication population and the relationship population. The findings suggest that the formation of relationship populations depends not on casual or repeated contact but on deeper forms of engagement that foster place attachment [95].

The continued return of repeat visitors after the pandemic suggests that Ōsawa is capable of fostering relationship populations. Once these ties are formed, they tend to be resilient and enduring, persisting even in the face of external disruptions. However, how to further encourage relationship populations to take on more active roles in local revitalization remains a key challenge for future rural policy and practice.

5.3.4. The Role of Locally Informed Experts and Supportive Institutions

The successful implementation of ikigai-zukuri requires not only local initiative but also enabling conditions that support it. To avoid overreliance on top-down interventions, external support should provide flexible resources in ways that respect and strengthen community-driven efforts.

Locally informed expert involvement is essential for empowering rural communities, particularly in understanding local rhythms, resource constraints, and emotional dynamics. Unlike conventional rural initiatives that rely on top-down technical expertise, the Ōsawa case illustrates the value of actors with deep local knowledge [107,108,109]. The inclusion of a local tea merchant, well-versed in both community dynamics and tea-related livelihoods, helped craft proposals that resonated with residents and fostered voluntary participation (Section 4.2.1). However, the lack of such hybrid “embedded experts” within municipal structures remains a challenge for long-term institutional continuity.

Policy-based institutional support, such as financial subsidies, technical guidance, and training programs, has also contributed to the project’s stability by lowering participation costs and incentivizing broader involvement (Section 4.2.3). Yet the effectiveness of such support depends on its responsiveness to local realities. When external interventions overlook community needs and emotional thresholds, they risk becoming performative or resisted [110]. The most impactful role for government is not directive, but enabling—offering flexible resources that reinforce, rather than replace, local initiatives.

The Ōsawa case shows that effective ikigai-zukuri relies on the coordinated roles of six key actors. Residents anchor daily practice and cultural continuity; relationship populations offer periodic support and reinforce family ties; exchange populations bring new contacts that may deepen into lasting relationships. Their combined engagement creates a bottom-up form of participation rooted in local life. Crucially, such processes require facilitation. Locally embedded experts help align external resources with community needs. Meanwhile, flexible institutional backing can reduce participation barriers while respecting local autonomy.

Together, these elements suggest that ikigai-zukuri, when grounded in everyday life and supported by locally appropriate mechanisms, can revitalize marginal settlements by enabling older residents to remain active, contribute meaningfully, and maintain social ties, rather than relying on large-scale investment or population return.

5.4. Landscapes of Participation: The Role of Cultural Space in Sustaining Ikigai-Zukuri

5.4.1. The Role of RCLs in Supporting Ikigai-Zukuri

In Ōsawa, the success of ikigai-zukuri was not only driven by social structures but also supported by the ongoing presence of a locally sustained cultural landscape. The continued cultivation of Zairai tea, use of engawa spaces, and preservation of everyday rural routines indicate that residents still value and identify with their cultural environment (Section 4.1.2, Section 4.1.3 and Section 4.1.4). This recognition suggests a latent sense of pride and attachment, an inner motivation that can be reactivated through ikigai-zukuri.

Moreover, the distinctiveness of the landscape itself serves as a cultural resource. Its aesthetic and symbolic qualities offer emotional grounding for residents and help attract and retain visitors (Section 4.3.4) [111]. Unlike preservation through regulation or tourism-led commodification, ikigai-zukuri utilizes the landscape through everyday livelihood practices.

This case shows that where local culture is still practiced and valued, cultural landscapes can function as both the basis and expression of sustainable, community-driven revitalization.

5.4.2. From Inhabitation to Involvement: Landscape as Shared Space

In Ōsawa, the continuity of the landscape is supported not only by local residents but also by exchange and relationship populations. Repeat visitors and returning out-migrated family members contribute through seasonal visits, informal support, and shared cultural activities (Section 4.3.4 and Section 4.3.5). These interactions turn the landscape into a relational space, shaped by emotional ties and mutual involvement.

What sustains the landscape is not its physical features alone but the social practices that keep it meaningful in people’s lives. Through ikigai-zukuri, daily routines, such as tea farming, cooking, or hosting, become ways for residents and outsiders to share the place. In doing so, the landscape evolves into a shared cultural asset where participation fosters connection, and connection reinforces care.

5.4.3. Ikigai-Zukuri as an RCL-Preserving Practice

The Engawa Café project illustrates that ikigai-zukuri can contribute to the preservation of RCLs. Rather than treating landscape elements as a static heritage to be protected or commodified through tourism [112,113], ikigai-zukuri sustains them as living, functional spaces embedded in daily life [114]. It aligns with the concept of a “continuing landscape” [70].

Older residents continue to engage in tea cultivation, food preparation, and place-based hospitality, not for economic gain, but as meaningful acts of contribution and connection. These practices, motivated by personal fulfillment and social recognition, maintain both the physical upkeep and symbolic continuity of the landscape. They also support rural integrity through the continued production of local agricultural goods, the conservation of land and biodiversity, the maintenance of circular ecological systems, and the sustenance of community life [115].

Although grounded in a rural Japanese context, this approach suggests a broader possibility: when people are supported to engage meaningfully with their local culture, ikigai-zukuri can help sustain both tangible and intangible heritage, especially in aging or shrinking communities.

5.5. Limitations of Ikigai-Zukuri

Despite the positive outcomes observed in Ōsawa, several limitations of the ikigai-zukuri approach must be acknowledged.

First, the sustainability of the initiative remains vulnerable due to its household-based structure and financial dependency. Participation relies heavily on the continued availability and health of older family members (Section 4.3.3), while operational costs are largely supported by national farmland subsidy schemes (Section 4.2.3). As agricultural land use continues to decline, access to such subsidies may become more uncertain, threatening long-term viability [116].

Second, the impact of the project has remained relatively localized. While it has successfully attracted returning out-migrated family members and repeat visitors, especially from nearby urban areas, its influence has yet to expand beyond a limited social circle (Section 4.3.4 and Section 4.3.5). Broader demographic and economic revitalization effects are still limited in scale.

Third, although the village’s Zairai tea fields and engawa spaces form a distinctive cultural landscape, their value remains under-recognized by both residents and policymakers (Section 4.1.2 and Section 4.1.3). Without efforts to reframe these assets as shared community resources, opportunities to broaden engagement and enhance the project’s cultural impact may be missed [111,117].

Finally, the model’s replicability remains uncertain. Ōsawa’s success rests on a combination of cultural continuity, internal cohesion, and the presence of locally embedded experts. In marginal settlements lacking such foundations, it is unclear whether ikigai-zukuri can be implemented with the same effect. Further research is needed to explore conditions for effective adaptation in diverse rural contexts.

6. Conclusions

In the face of accelerating depopulation, aging, and youth out-migration, ensuring the sustainable future of marginal settlements has become a critical challenge for rural revitalization in Japan and beyond. This study defines ikigai-zukuri as a community-based revitalization strategy that reactivates the social roles of older adults by leveraging family ties, cultural resources, and external support, offering a viable pathway for sustaining marginal settlements.

At the individual level, as the primary residents of marginal settlements, older adults are not passive recipients of care, but active agents. Rooted in local cultural contexts, their lifestyles, place-based identities, and everyday practices collectively shape a “continuing landscape” [70]. These everyday practices and identities became key resources not only for their own ikigai, but also for attracting visitors and reinforcing the village’s cultural value [118]. As shown in Section 4.3.4, many visitors to the Engawa Café were primarily motivated by the opportunity to interact with local residents. This underscores a central principle: people as a part of the local identity and maintaining traditional practices (Zairai tea); therefore, rural revitalization needs to begin by recognizing the value of older residents’ everyday practices and by strengthening the conditions that enable their continuity.

At the community level, the project was grounded in a stable and trust-based environment, where traditional mutual support systems—such as the Ōsawa Promotion Association (OPA) and the monthly yoriai meetings—allowed every resident to have a voice in decision-making, reinforcing a shared sense of agency and belonging. The household-based participation model enabled older adults to continue engaging in familiar tasks, while intergenerational collaboration revitalized family ties and reaffirmed the roles and status of elders within the home. These dynamics not only strengthened residents’ sense of purpose but also helped shape the community as a space for sustaining ikigai.