Relationship Between Perceived Authenticity, Place Attachment, and Tourists’ Environmental Behavior in Industrial Heritage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Foundation

2.1. Perceived Authenticity

2.2. Place Attachment

2.3. Environmentally Responsible Behavior (ERB)

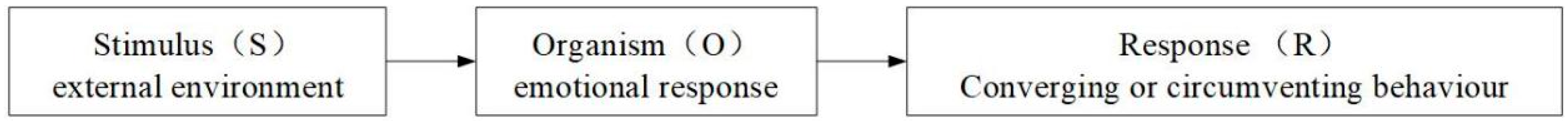

2.4. S-O-R Modelling

3. Research Hypotheses and Model Proposal

3.1. Perceived Authenticity and Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior

3.2. Object-Related Authenticity and Existential Authenticity

3.3. Perceived Authenticity and Place Attachment

3.4. Place Attachment and Environmentally Responsible Behavior

3.5. The Mediating Role of Place Attachment

4. Research Design

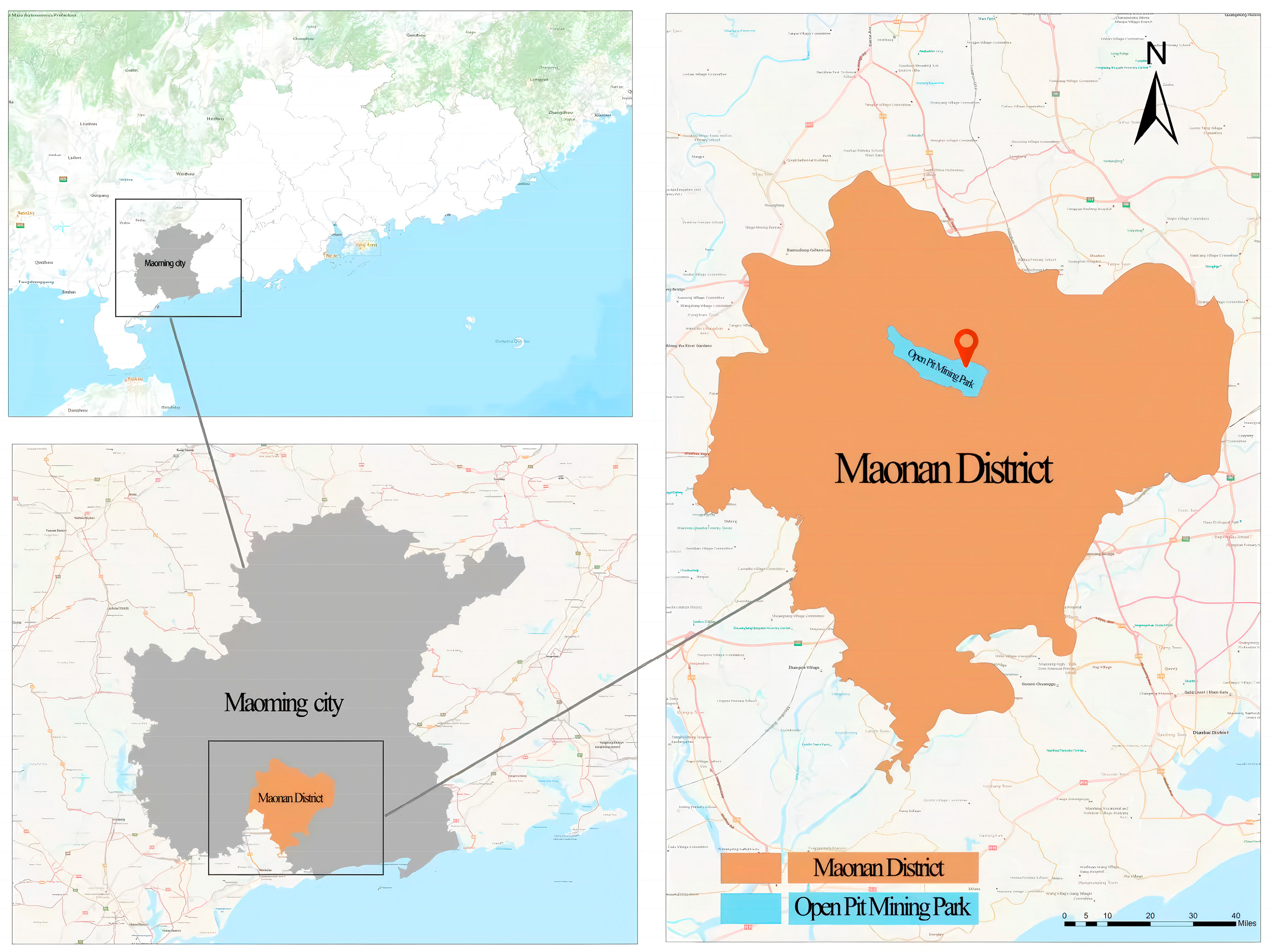

4.1. Overview of the Case Study Site

4.2. Questionnaire Design

4.3. Data Collection

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

5.2. Measurement Model Evaluation

5.3. Direct Effect Test

5.4. Mediating Effect Test

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions and Discussion

6.2. Theoretical Contributions

6.3. Practical Implications

6.4. Research Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GFI | Goodness of fit index |

| NFI | Normed fit index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis index |

| AVE | Average variance extracted |

| RMSEA | Root mean square error of approximation |

| AGFI | Adjusted goodness of fit index |

| CFI | Comparative fit index |

| IFI | Incremental fit index |

| CR | Composite reliability |

References

- Zhang, T.; Wei, C.; Nie, L. Experiencing authenticity to environmentally responsible behavior: Assessing the effects of perceived value, tourist emotion, and recollection on industrial heritage tourism. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1081464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, T.; Zabkar, V. A consumer-based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.-H. The Effects of Recreation Experience, Environmental Attitude, and Biospheric Value on the Environmentally Responsible Behavior of Nature-Based Tourists. Environ. Manag. 2015, 56, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, J.; Ccong, L. The effects of perceived value and place attachment on tourists’ environmental responsibility behaviors—A case study of Beijing Olympic Forest Park. Arid Zone Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Cheng, J.; Hu, D. Mechanism of service quality’s influence on tourists’ environmental responsibility behavior. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 41, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Fu, W.; Hong, S. A study on the relationship of landscape perception on the influence of park recreationists’ environmentally responsible behaviors—Taking Fuzhou Mountain Park as an example. For. Econ. 2021, 43, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, Y.; Björk, P.; Weidenfeld, A. Authenticity and place attachment of major visitor attractions. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H. Authenticity, satisfaction, and place attachment: A conceptual framework for cultural tourism in African island economies. Dev. South. Afr. 2015, 32, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Lin, V.S.; Jin, W.; Luo, Q. The Authenticity of Heritage Sites, Tourists’ Quest for Existential Authenticity, and Destination Loyalty. J. Travel Res. 2016, 56, 1032–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, X.; Wang, Q. A study on the relationship between perceived authenticity, place attachment and tourists’ loyalty—The case of “Five Avenues” in Tianjin. Enterp. Econ. 2021, 40, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhangsun, B.W.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Liang, J.X. Authenticity, place attachment and the tourists’ environmental responsibility behaviors in nature reserves. Issues For. Econ. 2023, 43, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, E.; Björk, P.; Coudounaris, D.N. Memorable nature-based tourism experience, place attachment and tourists’ environmentally responsible behaviour. J. Ecotour. 2022, 22, 542–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camatti, N.; di Tollo, G.; Gastaldi, F.; Camerin, F. Cultural heritage reuse applying fuzzy expert knowledge and machine learning: Venice’s fortresses case study. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2025, 12, 225–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.B.; Zhang, J.; Edelheim, J.R. Rethinking traditional Chinese culture: A consumerbased model regarding the authenticity of Chinese calligraphic landscape. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Zhou, Z. Influence of Authenticity Perception of Culture Tourism on Tourists’ Loyalty: The Mediating Effects of Tourists’ Well-being. J. Bus. Econ. 2018, 315, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.; Buchmann, A.; Månsson, M.; Fisher, D. Authenticity in tourism theory and experience. Practically indispensable and theoretically mischievous? Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 89, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M.; Hatamifar, P. Understanding memorable tourism experiences and behavioural intentions of heritage tourists. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 21, 100621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, A.; Yuksel, F.; Bilim, Y. Destination attachment: Effects on customer satisfaction and cognitive, affective and conative loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Weiler, B.; Smith, L.D.G. Place attachment and pro-environmental behaviour in national parks: The development of a conceptual framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, J.M.; Eisenhauer, B.W.; Stedman, R.C. Environmental Concern: Examining the Role of Place Meaning and Place Attachment. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borden, R.J.; Schettino, A.P. Determinants of Environmentally Responsible Behavior. J. Environ. Educ. 1979, 10, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, S.P.; Graefe, A.R. Testing a Conceptual Framework of Responsible Environmental Behavior. J. Environ. Educ. 1997, 29, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, O. Attitudinal Determinants Of Environmentally Responsible Behavior. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2001, 29, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H. How recreation involvement, place attachment and conservation commitment affect environmentally responsible behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qin, X.; Zhou, Y. A comparative study of relative roles and sequences of cognitive and affective attitudes on tourists’ pro-environmental behavioral intention. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 28, 727–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.-H.; Yang, C.-C. Conceptualizing and measuring environmentally responsible behaviors from the perspective of community-based tourists. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Jeong, E.; Kim, W. Environmentally Responsible Museums’ Strategies to Elicit Visitors’ Green Intention. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2018, 46, 1881–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, H.; Yayla, O.; Tarinc, A.; Keles, A. The Effect of Environmental Management Practices and Knowledge in Strengthening Responsible Behavior: The Moderator Role of Environmental Commitment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Wang, Y.; Shi, J.; Guo, W.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Z. Structural Relationship between Ecotourism Motivation, Satisfaction, Place Attachment, and Environmentally Responsible Behavior Intention in Nature-Based Camping. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, A.; Kılıçlar, A. The effect of tourists’ gastronomic experience on emotional and cognitive evaluation: An application of S-O-R paradigm. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2022, 6, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Hu, X.; Lee, H.M.; Zhang, Y. The Impacts of Ecotourists’ Perceived Authenticity and Perceived Values on Their Behaviors: Evidence from Huangshan World Natural and Cultural Heritage Site. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y. A study on the relationship between tourism authenticity, place attachment and tourists’ environmental responsibility behavior—Taking Hongcun in Huangshan City as an example. J. Huangshan Coll. 2024, 26, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Steiner, C.J. Reconceptualizing object authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Su, Y.; Ren, L.; Nijkamp, P. The influence of individual authenticity experience on tourists’ behavioral intentions: The chain mediating role of place dependence and place identity. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 28, 1279–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi-Feng, Z.; Zhi-Wei, L. Destination authenticity, place attachment and loyalty: Evaluating tourist experiences at traditional villages. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 26, 3887–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.E.; Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Cao, M. Examining the Antecedents of Environmentally Responsible Behaviour: Relationships among Service Quality, Place Attachment and Environmentally Responsible Behaviour. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Cheng, S.; Liu, Q. A study on the influence of social responsibility and local attachment on environmental responsibility behavior in tourist destinations—A case study of Yuelu Mountain Scenic Spot in Changsha. Geogr. Res. Dev. 2022, 41, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, A.; Gao, G.; Li, H.; Guo, Y. The effect of tourists’ perception of authenticity on loyalty: An integrative model. J. Tour. 2025, 40, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. The value and development and utilization of mining area under the perspective of industrial heritage protection—Taking the planning of open-pit mine ecological park in Maoming City, Guangdong as an example. Environ. Prot. 2017, 45, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yin, P. Testing the structural relationships of tourism authenticities. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The Measurement of Place Attachment: Validity and Generalizability of a Psychometric Approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakić, T.; Chambers, D. Rethinking the consumption of places. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1612–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Sun, G.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Q. Effect of tourism authenticity on tourist’s environmentally responsible behavior of traditional village: Roles of nostalgia and Taoist ecological value. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Sci. Ed.) 2022, 49, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaske, J.J.; Kobrin, K.C. Place Attachment and Environmentally Responsible Behavior. J. Environ. Educ. 2001, 32, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 177 | 46.30% |

| Female | 205 | 53.70% | |

| Age | 18–22 | 62 | 16.20% |

| 23–35 | 136 | 35.60% | |

| 36–45 | 83 | 21.70% | |

| 46–55 | 58 | 15.20% | |

| 56 years old and above | 43 | 11.30% | |

| Educational Attainment | High school and vocational school | 115 | 30.10% |

| College and undergraduate | 214 | 56% | |

| Postgraduate and above | 53 | 13.90% | |

| Occupation | Government and public institution employees | 74 | 19.40% |

| Enterprise/Company employees | 105 | 27.50% | |

| Students | 53 | 13.90% | |

| Freelancers | 86 | 22.50% | |

| Retired employees | 38 | 9.90% | |

| Other | 26 | 6.80% | |

| Income Situation | Below 2000 | 42 | 11% |

| 2001–5000 | 136 | 35.60% | |

| 5001–8000 | 92 | 24.10% | |

| 8001–10,000 | 67 | 17.50% | |

| Above 10,000 | 45 | 11.80% |

| Indicator | CMIN/DF | RMSEA | GFI | AGFI | NFI | CFI | TLI | IFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | <3 | <0.08 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 |

| Output | 2.87 | 0.036 | 0.978 | 0.97 | 0.979 | 0.986 | 0.983 | 0.986 |

| Judgement | Favorable | Favorable | Favorable | Favorable | Favorable | Favorable | Favorable | Favorable |

| Variable and Measurement Items | Factor Loading | t-Value | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Object-Related Authenticity (OA) | — | — | 0.906 | 0.658 | 0.901 |

| The original appearance of the open-pit mine ecological park left a deep impression on me. | 0.868 | — | — | — | — |

| I am very interested in the historical and cultural heritage of the open-pit mine ecological park. | 0.892 | 23.455 *** | — | — | — |

| I think the open-pit mine ecological park has unique local customs and practices. | 0.798 | 19.391 *** | — | — | — |

| I like the overall layout and greenery of the open-pit mine ecological park. | 0.831 | 20.74 *** | — | — | — |

| I enjoy the environment of the open-pit mine ecological park, which offers many interesting places to visit. | 0.643 | 14.055 *** | — | — | — |

| Existential Authenticity (EV) | — | — | 0.876 | 0.588 | 0.870 |

| I am very interested in the tourism activities of the open-pit mine ecological park. | 0.824 | — | — | — | — |

| I think the open-pit mine ecological park helps me understand industrial heritage. | 0.818 | 18.098 *** | — | — | — |

| I enjoy the unique natural experience in the open-pit mine ecological park. | 0.750 | 16.105 *** | — | — | — |

| I believe the open-pit mine ecological park provides a good spiritual experience. | 0.774 | 16.804 *** | — | — | — |

| I think the open-pit mine ecological park is closely related to human civilization. | 0.654 | 13.531 *** | — | — | — |

| Place Dependence (PD) | — | — | 0.879 | 0.595 | 0.871 |

| I think the open-pit mine ecological park is the ideal place for leisure. | 0.829 | — | — | — | — |

| I believe no other place can provide the environment and facilities that match the open-pit mine ecological park. | 0.788 | 12.583 *** | — | — | — |

| Compared to other places, I prefer the open-pit mine ecological park. | 0.808 | 12.889 *** | — | — | — |

| The open-pit mine ecological park is more suitable for various activities than other places. | 0.782 | 12.662 *** | — | — | — |

| Visiting the open-pit mine ecological park is more satisfying than visiting any other place. | 0.633 | 13.122 *** | — | — | — |

| Place Identity (PI) | — | — | 0.922 | 0.704 | 0.921 |

| I really like the open-pit mine ecological park. | 0.786 | — | — | — | — |

| The open-pit mine ecological park is very special to me. | 0.875 | 19.259 *** | — | — | — |

| The open-pit mine ecological park is full of wonderful memories for me. | 0.881 | 19.428 *** | — | — | — |

| Visiting the open-pit mine ecological park helps me reflect on the relationship between humans and nature. | 0.834 | 18.084 *** | — | — | — |

| The experience activities in the open-pit mine ecological park are very meaningful to me. | 0.815 | 17.557 *** | |||

| Environmentally Responsible Behavior (ERB) | — | — | 0.874 | 0.583 | 0.921 |

| I comply with the regulations to not damage the ecological environment of industrial heritage during my visit. | 0.682 | — | — | — | — |

| I do not litter while visiting the open-pit mine ecological park. | 0.708 | 16.082 *** | — | — | — |

| I discuss the environmental protection issues of the open-pit mine ecological park with my companions. | 0.842 | 16.485 *** | — | — | — |

| I am willing to participate in environmental protection activities at the open-pit mine ecological park. | 0.822 | 13.687 *** | — | — | — |

| I use my spare time to learn about environmental protection. | 0.750 | 13.143 *** | — | — | — |

| Variable | AVE | OA | EV | PD | PI | ERB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OA | 0.658 | 0.811 | ||||

| EV | 0.588 | 0.199 | 0.767 | |||

| PD | 0.595 | 0.296 | 0.753 | 0.771 | ||

| PI | 0.704 | 0.544 | 0.518 | 0.569 | 0.839 | |

| ERB | 0.583 | 0.525 | 0.513 | 0.653 | 0.675 | 0.764 |

| Hypothesis Path | Standardized Path Coefficient | Standard Error | t-Value | p-Value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: OA → ERB | 0.288 | 0.047 | 4.411 | *** | Supported |

| H2: EV → ERB | −0.037 | 0.075 | −0.475 | 0.635 | Unsupported |

| H3: OA → EV | 0.199 | 0.054 | 3.527 | *** | Supported |

| H4a: OA → PD | 0.146 | 0.03 | 3.442 | *** | Supported |

| H4b: OA → PI | 0.42 | 0.043 | 8.615 | *** | Supported |

| H5a: EV → PD | 0.754 | 0.05 | 10.968 | *** | Supported |

| H5b: EV → PI | 0.223 | 0.074 | 2.75 | 0.006 | Supported |

| H6: PD → PI | 0.27 | 0.106 | 3.176 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H7: PD → ERB | 0.43 | 0.114 | 4.874 | *** | Supported |

| H8: PI → ERB | 0.326 | 0.065 | 5.161 | *** | Supported |

| Effect | Hypothesis Path | Estimate Value | Path Product Relationship | Bias-Corrected 95% CI | Conclusions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Error | Z-Value | Lower | Upper | ||||

| Indirect Effect | H9a: OA → PD → ERB | 0.012 | 0.002 | 1.500 | −0.012 | 0.034 | Unsupported |

| H9b: OA → PI → ERB | 0.057 | 0.028 | 2.035 | 0.018 | 0.124 | Supported | |

| H9c: OA → PD → PI → ERB | 0.125 | 0.047 | 2.660 | 0.044 | 0.226 | Supported | |

| Total | OA → ERB | 0.194 | 0.053 | 3.660 | 0.100 | 0.300 | Supported |

| Indirect Effect | H10a: EV → PD → ERB | 0.063 | 0.031 | 2.032 | 0.011 | 0.153 | Supported |

| H10b: EV → PI → ERB | 0.307 | 0.103 | 2.981 | 0.150 | 0.559 | Supported | |

| H10c: EV → PD → PI → ERB | 0.069 | 0.034 | 2.029 | 0.009 | 0.188 | Supported | |

| Total | EV → ERB | 0.439 | 0.102 | 4.304 | 0.284 | 0.684 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qiu, N.; Wu, J.; Li, H.; Pan, C.; Guo, J. Relationship Between Perceived Authenticity, Place Attachment, and Tourists’ Environmental Behavior in Industrial Heritage. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115152

Qiu N, Wu J, Li H, Pan C, Guo J. Relationship Between Perceived Authenticity, Place Attachment, and Tourists’ Environmental Behavior in Industrial Heritage. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):5152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115152

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiu, Nengjie, Jiawei Wu, Haibo Li, Chen Pan, and Jiaming Guo. 2025. "Relationship Between Perceived Authenticity, Place Attachment, and Tourists’ Environmental Behavior in Industrial Heritage" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 5152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115152

APA StyleQiu, N., Wu, J., Li, H., Pan, C., & Guo, J. (2025). Relationship Between Perceived Authenticity, Place Attachment, and Tourists’ Environmental Behavior in Industrial Heritage. Sustainability, 17(11), 5152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115152