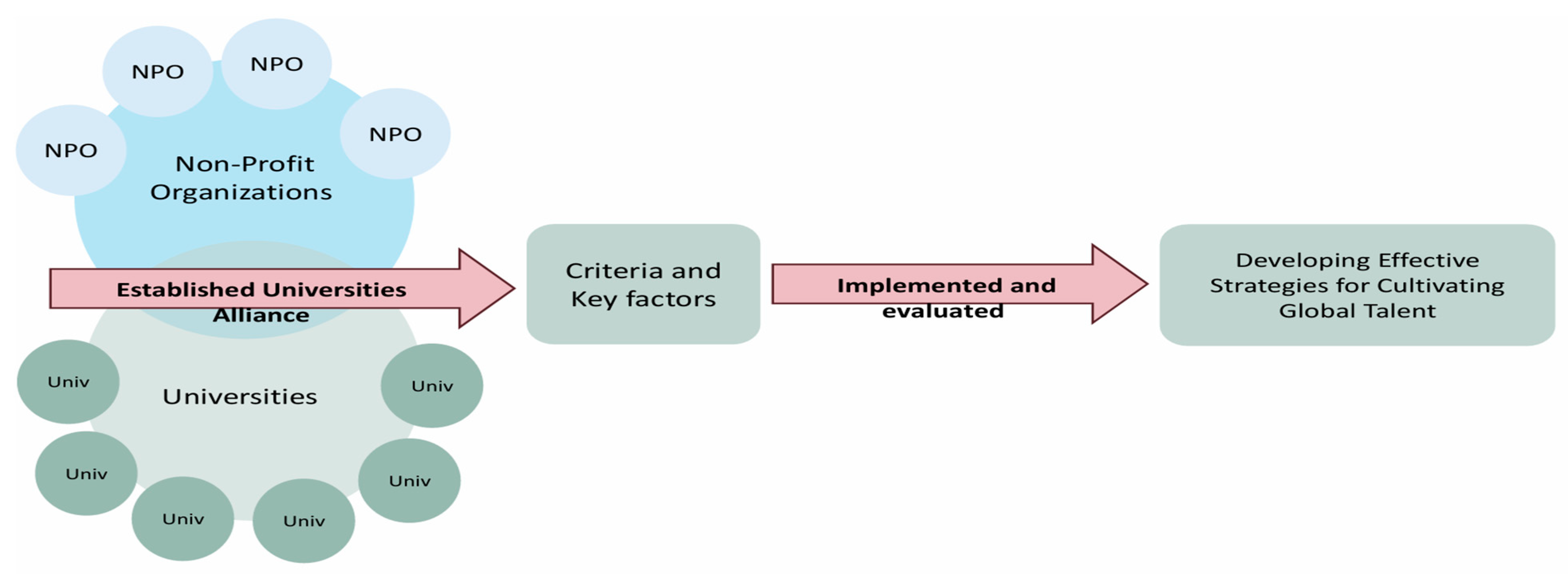

Sustainable Open Innovation Model for Cultivating Global Talent: The Case of Non-Profit Organizations and University Alliances

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Application of the Open Innovation Model

2.2. Strategic Planning for Global Talent Cultivation Through Non-Profit Organizations

2.3. The Role of the University Alliance in Global Education

3. Methodology

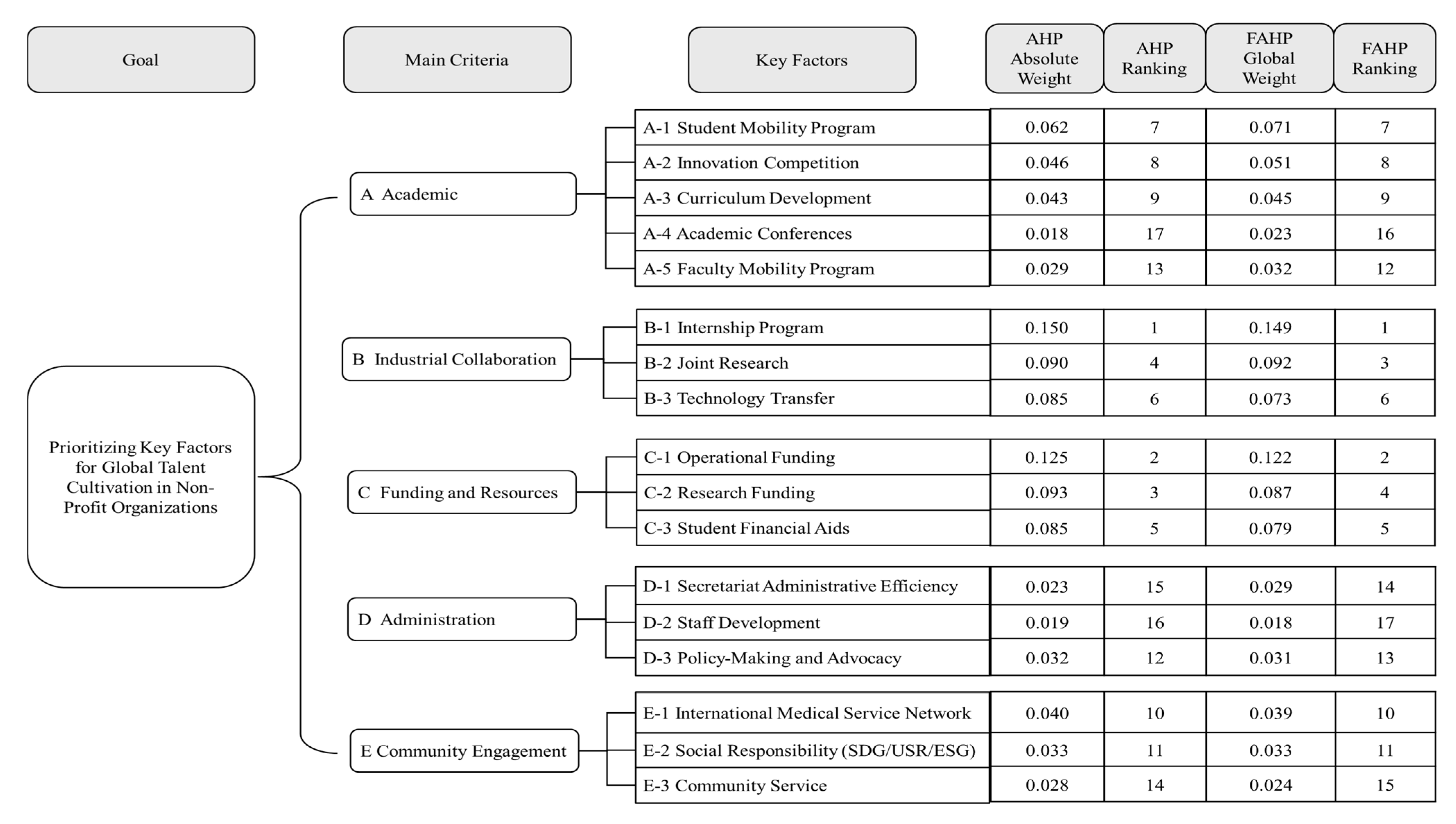

3.1. Identifying Criteria and Key Factors

3.1.1. Academic

3.1.2. Industrial Collaboration

3.1.3. Funding and Resources

3.1.4. Administration

3.1.5. Community Engagement

3.2. Comparison of AHP and Fuzzy AHP

3.2.1. Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP)

3.2.2. Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process (FAHP)

4. Research Analysis and Result

4.1. AHP and FAHP Structural Weight Analysis

4.2. Comparative Analysis of AHP and FAHP Using Local Weights

4.2.1. The Role of Local and Global Weights in AHP and FAHP: A Dual-Level Analytical Approach for Decision Making

4.2.2. Criteria Weight Analysis

4.3. Sub-Criteria Weight Measurement Analysis

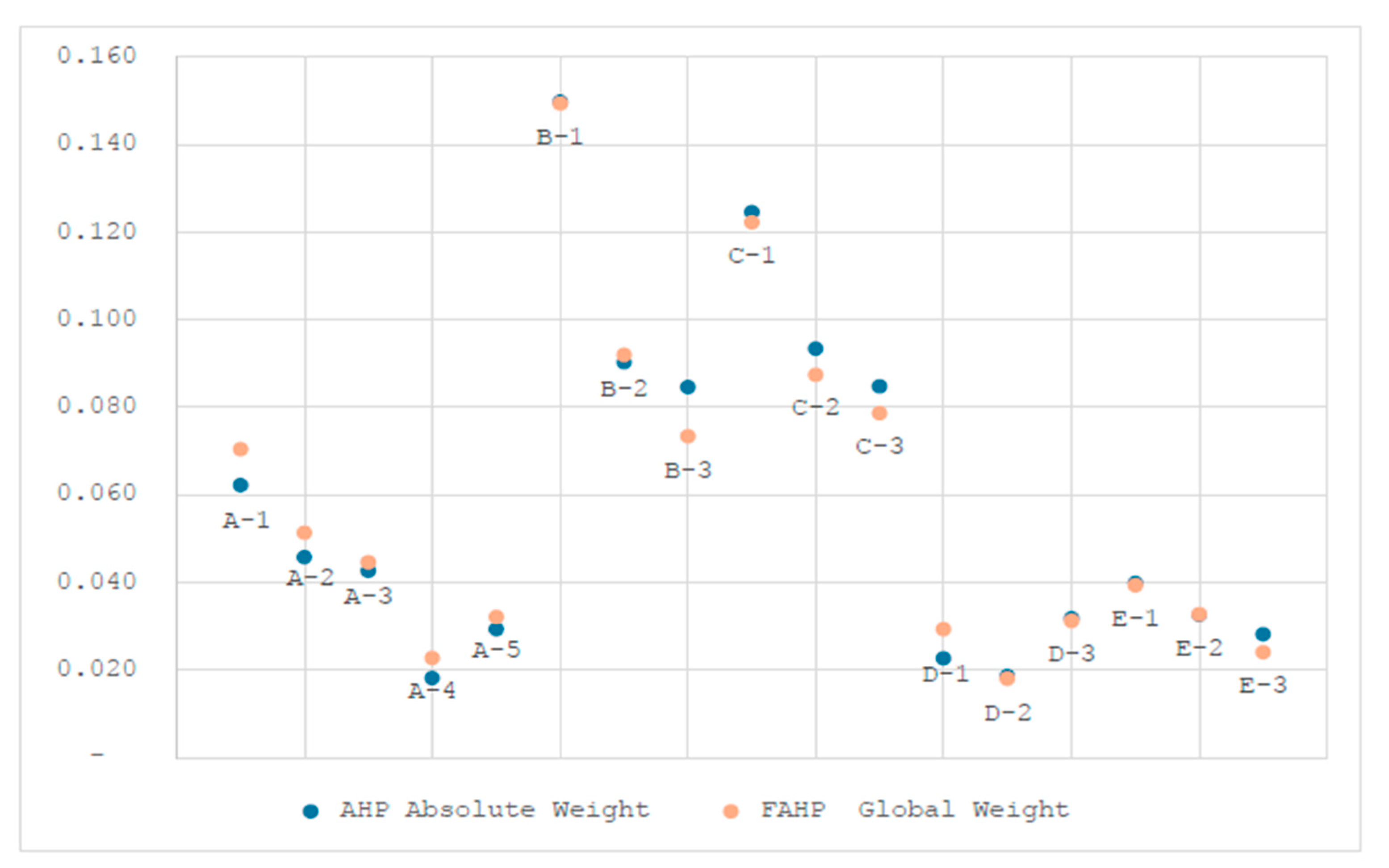

4.4. Analysis of Weight Distribution Among All Factors

5. Discussion

5.1. Contextualizing Results Within Existing Literature

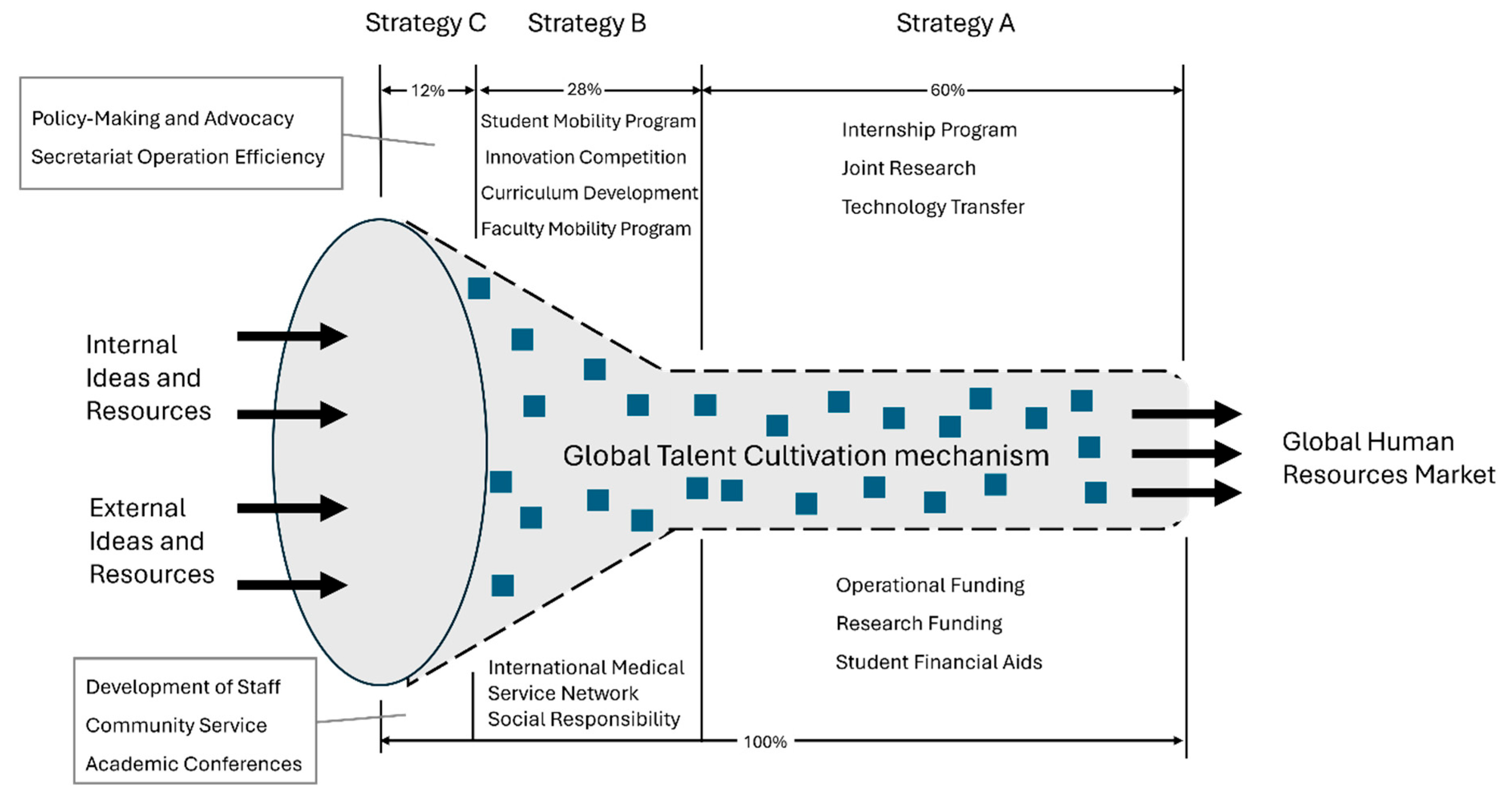

5.2. Forming an Open Innovation Strategic Model

5.2.1. Strategy A: Collaborative Strategies

5.2.2. Strategy B: Interactive Strategies

5.2.3. Strategy C: Foundational Strategies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Collins, A.; Halverson, R. Rethinking Education in the Age of Technology: The Digital Revolution and Schooling in America; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Olson, C.; Kroeger, K.R. Global competency and intercultural sensitivity. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2001, 5, 116–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. The logic of open innovation: Managing intellectual property. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2003, 45, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, J.M. Strategic Planning for Public and Nonprofit Organizations: A Guide to Strengthening and Sustaining Organizational Achievement; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng, C.H. Pollution haven, private politics, and competitive dynamics: How do irresponsible MNEs challenged by an international NGO compete to act responsibly? Manag. Int. Rev. 2024, 64, 871–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassmann, O.; Enkel, E. Towards a theory of open innovation: Three core process archetypes. RD Manag. Conf. 2004, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.; Brunswicker, S. A fad or a phenomenon? The adoption of open innovation practices in large firms. Res. Technol. Manag. 2014, 57, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhaverbeke, W.; Chesbrough, H.; West, J. New Frontiers in Open Innovation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.; Bogers, M. Explicating open innovation: Clarifying an emerging paradigm for understanding innovation. In New Frontiers in Open Innovation; Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., West, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. The future of open innovation: The future of open innovation is more extensive, more collaborative, and more engaged with a wider variety of participants. Res. Technol. Manag. 2017, 60, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renjini, D. Market Orientation of Nonprofit Organizations: An Indian Perspective; Vernon Press: Malaga, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Todeva, E.; Knoke, D. Strategic alliances and models of collaboration. Manag. Decis. 2005, 43, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, T. Civic Responsibility and Higher Education; Greenwood Publishing Group: Westport, CT, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, P.A. Leveraging Paradoxical Tensions: An Ethnographic Case Study of a Private Nonprofit US Higher Education Institution. Ph.D. Thesis, Creighton University, Omaha, NE, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. How to reinvent capitalism—And unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Manag. Sustain. Bus. 2011, 323. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.; Stevenson, H.; Wei–Skillern, J. Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different, or both? Entrepr. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansoff, H.I. The Concept of Strategy; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G. External control of organizations: Resource dependence perspective. In Organizational Behavior 2; Miner, J.B., Ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015; pp. 355–370. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, B.A. Teachers’ use of textbooks in the digital age. Cogent Educ. 2015, 2, 1015812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, S. Higher education and public good. High. Educ. Q. 2011, 65, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jon, J.E. Power dynamics with international students: From the perspective of domestic students in Korean higher education. High. Educ. 2012, 64, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.J.; Meyer, J.W. The University and the Global Knowledge Society; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Charney, A.H.; Libecap, G.D. The contribution of entrepreneurship education: An analysis of the Berger program. Int. J. Entrep. 2003, 1, 385–417. [Google Scholar]

- Trowler, P. Academic tribes and territories: The theoretical trajectory. Österr. Z. Geschichtswiss. 2014, 25, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- De Wit, H.; Altbach, P.G. Internationalization in higher education: Global trends and recommendations for its future. Policy Rev. High. Educ. 2021, 5, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunaratne, K.; Perera, N. Students’ perception on the effectiveness of industrial internship programme. Educ. Q. Rev. 2019, 2, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The dynamics of innovation: From National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.; Bogers, M.L.; Jennings, P.D.; Xue, L. Technology transfer from national/federal labs and public research institutes: Managerial and policy implications. Res. Policy 2003, 52, 104646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazzafi, S. Consumer buying decision process toward products. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Dev. 2019, 2, 130–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, C.; Sørensen, M.P. The size of research funding: Trends and implications. Sci. Public Policy 2015, 42, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, D.B.; Marcucci, P.N. Financing Higher Education Worldwide: Who Pays? Who Should Pay? Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, P.F. Lessons for successful nonprofit governance. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 1990, 1, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, D.; Hirsh, S. A New Vision for Staff Development; Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development: Alexandria, VA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jansson, A. Mediatization as a framework for social design: For a better life with media. Des. Cult 2018, 10, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qodirov, F.; Muhitdinov, X. Features that increase efficiency in the provision of medical services and factors affecting them. Ta’lim Rivojl. Tahlil. Online Ilmiy J. 2022, 2, 192–199. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Lee, N. Best of breed: When it comes to gaining a market edge while supporting a social cause “corporate social marketing” leads the pack. Soc. Mark. Q. 2005, 11, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringle, R.G.; Hatcher, J.A. Campus–community partnerships: The terms of engagement. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 58, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. The analytic hierarchy process: What it is and how it is used. Math. Model. 1987, 9, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, G.H.; Teng, J.Y. Transportation investment project selection with fuzzy multiobjectives. Transp. Plan. Technol. 1993, 17, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.K.; Agrawal, S.; Gupta, R.D. Comparison of GIS-based AHP and fuzzy AHP methods for hospital site selection: A case study for Prayagraj City, India. GeoJournal 2021, 87, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinogradova-Zinkevič, I.; Podvezko, V.; Zavadskas, E.K. Comparative assessment of the stability of AHP and FAHP methods. Symmetry 2021, 13, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashek-Al-Aziz, M. A comparative study on AHP and FAHP for consistent and inconsistent data. Int. J. Comput. Inf. Technol. 2014, 5, 140702. [Google Scholar]

- Bonzano, A.; Cunningham, P.; Smyth, B. Learning feature weights for CBR: Global versus local. In Proceedings of the AI* IA 97: Advances in Artificial Intelligence: 5th Congress of the Italian Association for Artificial Intelligence, Rome, Italy, 17–19 September 1997; Saitta, L., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 417–426. [Google Scholar]

| Criteria | Key Factors |

|---|---|

| A. Academic | A-1 Student Mobility Programs |

| A-2 Innovation Competition | |

| A-3 Curriculum Development | |

| A-4 Academic Conferences | |

| A-5 Faculty Mobility Programs | |

| B. Industry Collaboration | B-1 Internship Programs |

| B-2 Joint Research Projects | |

| B-3 Technology Transfer | |

| C. Funding and Resources | C-1 Operational Funding |

| C-2 Research Funding | |

| C-3 Student Financial Aids | |

| D. Administration | D-1 Secretariat Operation Efficiency |

| D-2 Staff Development | |

| D-3 Policy Making and Advocacy | |

| E. Community Engagement | E-1 International Medical Service Network |

| E-2 Social Responsibility | |

| E-3 Community Service |

| No | Position | Institute | Category | Year of Experience | Education Level | Gender | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | President | National Pintung University | Education | >30 | PHD | Male | 60–70 |

| 2 | President | Jinwen University | Education | >30 | PHD | Female | 60–70 |

| 3 | Vice President | National Central University | Education | >30 | PHD | Male | 60–70 |

| 4 | Vice President | National Tsing Hua University | Education | >30 | PHD | Male | 60–70 |

| 5 | Vice President | Chung Yuan Christian University | Education | >30 | PHD | Male | 60–70 |

| 6 | Former Chairman | Taiwan Power Company | Corporate | >30 | PHD | Male | 70-80 |

| 7 | Chairman | Martas Precision Slide Co., Ltd. | Corporate | >40 | Master | Male | 60–70 |

| 8 | General Manager | 3D IC Lab | Corporate | >10 | PHD | Male | 40–50 |

| 9 | Chairwoman | Global Federation of Chinese Business Woman | NPO | >20 | PHD | Female | 60–70 |

| 10 | Chairman | Green Tourism Association of Taiwan | NPO | >30 | PHD | Male | 60–70 |

| 11 | Executive Director | Saylingwen Cultural and Educational Foundation | NPO | >30 | Master | Male | 60–70 |

| 12 | Senor Director | UAiTED University Alliance | NPO | >10 | Master | Female | 40–50 |

| n | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| R.I. | 0 | 0 | 0.58 | 0.9 | 1.12 | 1.24 | 1.32 | 1.41 | 1.45 | 1.49 | 1.51 | 1.58 | 1.56 | 1.57 | 1.58 | 1.58 | 1.58 |

| Scale | Definition | Triangular Fuzzy Numbers | Scale Reciprocal | Reciprocal of Triangular Fuzzy Numbers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Equally Important | (1, 1, 1) | 1 | (1, 1, 1) |

| 2 | (1, 2, 3) | 1/2 | (1/3, 1/2, 1) | |

| 3 | Slightly Important | (2, 3, 4) | 1/3 | (1/4, 1/3, 1/2) |

| 4 | (3, 4, 5) | 1/4 | (1/5, 1/3, 1/3) | |

| 5 | Strongly Important | (4, 5, 6) | 1/5 | (1/6, 1/5, 1/4) |

| 6 | (5, 6, 7) | 1/6 | (1/7, 1/6, 1/5) | |

| 7 | Very Strongly Important | (6, 7, 8) | 1/7 | (1/8, 1/7, 1/6) |

| 8 | (7, 8, 9) | 1/8 | (1/9, 1/8, 1/7) | |

| 9 | Extremely Important | (8, 9, 9) | 1/9 | (1/9, 1/9, 1/8) |

| Feature | AHP | FAHP |

|---|---|---|

| Type of Input | Crisp (exact) pairwise comparisons | Fuzzy numbers (Triangular Fuzzy Numbers—TFNs) |

| Handling Uncertainty | Less effective in handling uncertainty and subjectivity | Better for subjective and imprecise judgments |

| Pairwise Comparison Scale | Uses Saaty’s 1–9 scale | Uses Triangular Fuzzy Numbers (TFNs) |

| Mathematical Model | Uses Eigenvalue Method | Uses Fuzzy Logics and Defuzzification Methods (e.g., Chang’s Extent Analysis, Lambda-Max, etc.) |

| Consistency Check | Requires Consistency Ratio (CR) < 0.1 | More flexible with consistency since fuzzy logic inherently manages vagueness |

| Application Suitability | Works well when expert judgment is precise | Ideal when expert judgment is vague, linguistic, or uncertain |

| Scenario | Precise and well-defined criteria | Uncertainty in decision making (e.g., expert opinions vary significantly) |

| Small number of decision makers with high agreement | Large group decision making with subjective opinions | |

| Crisp and numerical data available | Linguistic terms used in judgment (e.g., “Moderately Important”, “Very Important”) |

| Criterion | AHP Absolute Weight | FAHP Global Weight | Weight Difference | Deviation (%) | Uncertainty Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-1 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 25 | High |

| C-1 | 0.11 | 0.095 | 0.015 | 13.63636 | Moderate |

| C-2 | 0.1 | 0.085 | 0.015 | 15 | Moderate |

| A-1 | 0.06 | 0.045 | 0.015 | 25 | High |

| D-1 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 33.33333 | High |

| E-2 | 0.025 | 0.035 | 0.01 | 40 | High |

| B-2 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 11.11111 | Moderate |

| B-3 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 12.5 | Moderate |

| C-3 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 11.11111 | Moderate |

| Feature | AHP Local Weight | AHP Global Weight | FAHP Local Weight | FAHP Global Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Importance within a specific category | Overall importance in the entire hierarchy | Importance within a specific category | Overall importance in the entire hierarchy |

| Calculation | Derived from pairwise comparisons inside a category | Local weight multiplied by the main criterion’s weight | Derived from pairwise comparisons within a single category | Local weight multiplied by the parent criterion’s weight |

| Scope | Relative ranking inside a category | Absolute ranking in the full decision model | Relative ranking inside a category | Absolute ranking in the whole system |

| Summation | Local weights sum to 1 within each category | Global weights sum to 1 across all categories | Local weights sum to 1 within a category | Global weights sum to 1 across all categories |

| Use Case | Helps compare importance inside a category | Used for final ranking and decision-making | Helps in understanding priorities within a main criterion | Helps in determining overall priority in the decision-making system |

| Evaluation Criteria | Key Factors | AHP Weight | AHP Relative Ranking | FAHP Local Weight | FAHP Relative Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic | A-1 Student Mobility Program | 0.314 | 1 | 0.318 | 1 |

| A-2 Innovation Competition | 0.231 | 2 | 0.232 | 2 | |

| A-3 Curriculum Development | 0.215 | 3 | 0.202 | 3 | |

| A-4 Academic Conferences | 0.092 | 5 | 0.103 | 5 | |

| A-5 Faculty Mobility Program | 0.148 | 4 | 0.145 | 4 | |

| Industry Collaboration | B-1 Internship Program | 0.461 | 1 | 0.475 | 1 |

| B-2 Joint Research | 0.278 | 2 | 0.292 | 2 | |

| B-3 Technology Transfer | 0.261 | 3 | 0.233 | 3 | |

| Funding and Resources | C-1 Operational Funding | 0.411 | 1 | 0.424 | 1 |

| C-2 Research Funding | 0.309 | 2 | 0.303 | 2 | |

| C-3 Student Financial Aids | 0.280 | 3 | 0.273 | 3 | |

| Administration | D-1 Secretariat Operation Efficiency | 0.310 | 2 | 0.374 | 2 |

| D-2 Development of Staff | 0.255 | 3 | 0.229 | 3 | |

| D-3 Policy-Making and Advocacy | 0.436 | 1 | 0.397 | 1 | |

| Community Engagement | E-1 International Medical Service Network | 0.396 | 1 | 0.409 | 1 |

| E-2 Social Responsibility | 0.324 | 2 | 0.341 | 2 | |

| E-3 Community Service | 0.280 | 3 | 0.251 | 3 |

| Evaluation Criteria | Criteria | AHP Local Weight | Relative Ranking | FAHP Local Weight | Relative Ranking | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | A | Academic | 0.198 | 3 | 0.222 | 3 |

| B | Industry Collaboration | 0.325 | 1 | 0.315 | 1 | |

| C | Funding and Resources | 0.303 | 2 | 0.289 | 2 | |

| D | Administration | 0.073 | 5 | 0.079 | 5 | |

| E | Community Engagement | 0.101 | 4 | 0.096 | 4 | |

| Key Factors | AHP Absolute Weight | AHP Absolute Ranking | FAHP Global Weight | FAHP Global Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-1 Internship Program | 0.150 | 1 | 0.149 | 1 |

| C-1 Operational Funding | 0.125 | 2 | 0.122 | 2 |

| B-2 Joint Research | 0.090 | 4 | 0.092 | 3 |

| C-2 Research Funding | 0.093 | 3 | 0.087 | 4 |

| C-3 Student Financial Aids | 0.085 | 5 | 0.079 | 5 |

| B-3 Technology Transfer | 0.085 | 6 | 0.073 | 6 |

| A-1 Student Mobility Program | 0.062 | 7 | 0.071 | 7 |

| A-2 Innovation Competition | 0.046 | 8 | 0.051 | 8 |

| A-3 Curriculum Development | 0.043 | 9 | 0.045 | 9 |

| E-1 International Medical Service Network | 0.040 | 10 | 0.039 | 10 |

| E-2 Social Responsibility | 0.033 | 11 | 0.033 | 11 |

| A-5 Faculty Mobility Program | 0.029 | 13 | 0.032 | 12 |

| D-3 Policy Making and Advocacy | 0.032 | 12 | 0.031 | 13 |

| D-1 Secretariat Operation Efficiency | 0.023 | 15 | 0.029 | 14 |

| E-3 Community Service | 0.028 | 14 | 0.024 | 15 |

| A-4 Academic Conferences | 0.018 | 17 | 0.023 | 16 |

| D-2 Development of Staff | 0.019 | 16 | 0.018 | 17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, C.-W.; Liu, P.-T.; Thy, Y.-H.; Peng, C.L. Sustainable Open Innovation Model for Cultivating Global Talent: The Case of Non-Profit Organizations and University Alliances. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5094. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115094

Lee C-W, Liu P-T, Thy Y-H, Peng CL. Sustainable Open Innovation Model for Cultivating Global Talent: The Case of Non-Profit Organizations and University Alliances. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):5094. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115094

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Cheng-Wen, Pei-Tong Liu, Yin-Hsiang Thy, and Choong Leng Peng. 2025. "Sustainable Open Innovation Model for Cultivating Global Talent: The Case of Non-Profit Organizations and University Alliances" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 5094. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115094

APA StyleLee, C.-W., Liu, P.-T., Thy, Y.-H., & Peng, C. L. (2025). Sustainable Open Innovation Model for Cultivating Global Talent: The Case of Non-Profit Organizations and University Alliances. Sustainability, 17(11), 5094. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115094