Abstract

Project-based learning (PBL) is a student-centered, inquiry-based approach in which students design and execute projects that address meaningful challenges. Over time, PBL has been adapted across various educational levels, disciplines, and cultural contexts, leading to a diverse body of knowledge. Given these variations, it is crucial to systematize existing research to identify well-established aspects and areas that require further exploration. This study conducts a systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) methodology. It uses the foundational PBL model as a reference to analyze its essential elements in design and implementation, particularly in terms of their contribution to sustainable education. A total of 25 studies were included in the final review sample. The research aims to examine current practices and identify gaps or inconsistencies in application. The qualitative analysis highlights crucial aspects such as project design, evaluation strategies, and interdisciplinary alignment. Findings reveal challenges in ensuring consistency across practices, with a predominant focus on procedural execution. However, the review also uncovers that existing studies address cognitive and socio-emotional dimensions in ways that require further investigation. Based on these findings, the study proposes a refined framework for the implementation of PBL, aiming to guide more effective and context-sensitive applications. These findings underscore the need for further exploration of how PBL can holistically support learner growth, enhance engagement, and contribute to more sustainable and impactful educational practices. Theoretical implications point to a deeper understanding of how PBL can integrate cognitive, emotional, and interdisciplinary components to foster this holistic development, while operational implications highlight the importance of institutional support, teacher training, and flexible curricular policies to ensure successful and sustainable implementation.

1. Introduction

The interest in implementing project-based learning arises from the need to shift from educational approaches based on the transmission of knowledge towards methodologies where the student plays a more active role, which promote meaningful and reflective learning, as well as greater interaction among teachers, students, and the community [1,2]. Rooted in socio-constructivist principles, this transition emphasizes meaningful learning and the construction of knowledge through social interaction and problem-solving in real contexts [3,4]. While PBL draws on historical educational philosophies such as Dewey’s “learning by doing” and Kilpatrick’s Project Method [5], current discourse emphasizes how these principles are operationalized today to meet 21st century learning needs.

Innovation and action are pivotal in driving this transition towards renewed educational practices. In this line, PBL stands out as a strategy that transcends conventional classroom boundaries, creating an educational setting that “… takes students outside of the traditional classroom environment and into a vibrant, experimental one” [6] (p.1), thus responding to this call to action in a new framework that puts the student at the center of their learning process, while promoting cognitive competencies and social and affective development [7]. Given the current global context, aligning PBL with sustainability goals is essential for equipping learners with the competencies required to address real-world challenges. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 4 emphasizes inclusive, equitable, and quality education, which can be effectively supported through interdisciplinary and inquiry-driven approaches such as PBL.

PBL is widely recognized today as a pedagogical approach capable of fostering deep, competency-based learning. The Gold Standard PBL framework proposed by Larmer et al. [8] provides a structured foundation built around seven essential design elements, such as a challenging problem or question, sustained inquiry, authenticity, student voice and choice, reflection, critique and revision, and the creation of a public product, that together promote authentic, inquiry-driven educational experiences. Beyond the core elements of the Gold Standard, rigorous PBL requires the application of specific strategies such as task management, scaffolding, collaborative methods, and assessment tools [9]. Moreover, experts emphasize that the success of PBL implementation depends on additional factors, such as the number of implementation stages, the educational context, detailed understanding of students and teachers, institutional support, and the availability of resources [6,8,10,11]. Understanding how these layers interact and are implemented in diverse educational settings is critical to refining PBL practices and ensuring their effectiveness in fostering deep and meaningful learning experiences. However, despite growing evidence of PBL’s potential, its implementation remains uneven across educational settings. A recent meta-analysis highlighted how PBL impacts differ across educational levels: in elementary learners, it strengthens collaborative skills; in middle school, it enhances creativity, critical thinking, and cooperative spirit; and in high school, it significantly boosts critical reasoning [12]. These findings also reveal that many variables, including family background, teacher preparation, and available resources, moderate these outcomes, suggesting that current PBL practices are far from standardized. This underscores the need for a systematic review that maps implementation patterns and evaluates the degree of fidelity to foundational PBL principles.

PBL implementation is further hampered by a number of regulatory, organizational, social, and contextual challenges, which hinders its applicability in certain educational settings. Among the most commonly encountered challenges, resistance to change from educators, administrators, and families fosters a social dialog that needs an objective and accurate response grounded in a comprehensive analysis of the situation [13]. Likewise, uncertainties regarding students’ effective acquisition of knowledge and the development of competencies, coupled with insufficient material, and technological and financial resources, further complicate the implementation of project-based learning [14]. The pressure to comply with benchmark assessments, often misaligned with project-based learning principles [15], is generating conflicts in the adoption of this methodological approach. Though research indicates that effective PBL fosters problem-solving skills, engagement, and deeper learning [16,17], its impact on standardized assessments remains contested, with some studies highlighting teachers’ lack of expectation that students will perform better on standardized tests when working with PBL [18], while others suggest that students who engage in PBL tend to perform better on traditional exams compared to their peers in more conventional learning environments [8].

Another critical barrier to effective implementation of PBL lies in the planning and execution of projects. Teachers often encounter challenges in designing and facilitating PBL, largely due to limited professional development and insufficient methodological training [9]. Moreover, time constraints and curricular rigidity pose additional hurdles, as the lack of opportunities for collaborative planning among teachers significantly hinders their capacity to design and implement high-quality projects, which requires more extensive planning and flexibility than traditional instruction [1,19]. Additionally, stakeholders’ perceptions and roles significantly influence PBL’s adoption and sustainability. While students often report higher engagement, motivation, and fun [20], educators and school leaders may express hesitations due to regulatory constraints and the absence of institutional support [21,22]. Policymakers, in turn, grapple with the challenge of integrating PBL into existing educational frameworks while ensuring equity and effectiveness across diverse learning contexts [23]. These systemic challenges highlight the need for a structured and systematic examination of how PBL is being implemented and whether its practical aspects align with the theoretical foundations that define it.

In this context, it is crucial to evaluate and organize existing knowledge on how PBL is implemented in various educational settings, as reflected in the current scientific literature. Understanding whether the practices identified as PBL adhere to its foundational principles or deviate from its theoretical conception is essential [19]. Furthermore, it is imperative to examine whether PBL-based interventions tend to prioritize certain dimensions of learning over others, such as emphasizing the development of specific competencies at the expense of theoretical knowledge acquisition or vice versa.

Equally important is the examination of the impact of these practices on learning outcomes, as well as on the attributions that different educational stakeholders—teachers, administrators, students, and policymakers—make about the effectiveness of PBL. This approach not only enables the identification of patterns and trends in its implementation but also provides a robust foundation for the development of strategies that enhance the reach, equity, and effectiveness of this pedagogical method across a wide array of educational contexts. In addition, understanding how PBL supports the development of competencies such as collaboration, critical thinking, and social responsibility allows for its implementation to be effectively aligned with the broader goals of sustainable education. In this sense, analyzing PBL’s effectiveness necessarily involves evaluating and reflecting on its proven capacity to promote inclusive, relevant, and future-oriented learning that prepares students to contribute meaningfully to sustainable development.

Thus, conducting a systematic review not only provides a rigorous analytical basis, but also represents a sustainable strategy in educational research, as it draws upon existing evidence to organize dispersed knowledge. By doing so, it minimizes redundancy and supports the development of a more integrative and adaptable implementation framework. While this study concentrates on the implementation of PBL, it is important to acknowledge that such implementation can have significant implications for the cognitive [24] and socio-emotional [25] domains. How these dimensions are affected by different approaches to PBL implementation remains an important area for future research.

Therefore, rather than assuming a predefined balance between these dimensions, this study critically examines how existing PBL models privilege certain aspects over others, which may have implications for the development of a more integrative and equitable framework. By focusing on implementation, the study questions the underlying assumptions of these models and evaluates whether their emphasis on specific dimensions aligns with the broader objectives of PBL. In doing so, it lays the groundwork for a more systematic mapping of PBL’s key dimensions, providing valuable insights for the improvement of pedagogical strategies and the formulation of educational policies that promote more comprehensive, sustainable, and effective applications of PBL in diverse educational contexts [8,13,26].

To this end, the following research questions (RQs) are proposed:

- RQ1. How are the core elements of PBL being integrated into educational institutions according to the scientific literature?

- RQ2. Is PBL truly being conducted when it is claimed to be?

- RQ3. What are the critical gaps or imbalances in the implementation of PBL, and how might these be addressed to better support knowledge acquisition and competency development?

- RQ4. How do the identified implementation patterns influence learning outcomes and the perceptions of PBL’s effectiveness across diverse and sustainable learning contexts?

The research questions were developed based on a preliminary analysis of the field and are aligned with current theoretical and practical challenges in PBL implementation. Their formulation allows for a qualitative exploration of both structural and pedagogical dimensions, ensuring relevance and feasibility within the scope of a systematic review.

Accordingly, the subsequent sections develop the methodological approach adopted (Section 2), present the results in relation to the proposed research questions (Section 3), offer a critical discussion of the main findings (Section 4), and conclude with the principal implications and directions for future research (Section 5).

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review aims to explore existing models and practices related to PBL, with a particular focus on identifying the essential elements of its design and implementation [27]. The study critically examines how PBL is applied in educational institutions including pre-school, primary, secondary, and tertiary education. It mainly explores its practical application, evaluating its authenticity when claimed to be implemented. It first systematizes existing studies to identify patterns and inconsistencies, followed by a directed content analysis based on the frameworks established by leading PBL scholars [9]. Our study applies the Gold Standard PBL framework alongside key implementation components, and critical success factors to ensure a rigorous evaluation of PBL in educational settings [6,10,11]. By adhering to this research-based model, we aim to assess the extent to which PBL practices align with established best practices, measuring their fidelity to core principles. Furthermore, our research questions seek to identify challenges that may hinder the effective and consistent application of PBL in contemporary education, offering insights into its real-world implementation and impact.

2.1. Procedure

The methodology applied is based on systematic literature review studies [28] within a qualitative design. It focuses on the most recent theoretical and practical advances in the implementation of PBL in educational centers over the past decade. This approach differs from traditional narrative reviews by being less prone to bias, more objective and detailed, and more rigorous and explicit in the criteria used for the inclusion of studies [29]. The study was conducted in two main stages. In the first stage, the study’s main objective, research questions, and inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined. This stage also encompassed the design of the search strategy and the identification of relevant databases and search terms, following the PRISMA guidelines, in order to ensure the validity and rigor throughout the workflow [30]. The literature search was carried out using two major academic databases: Web of Science (WOS) and SCOPUS. Eligibility criteria and search strategies were established using the Participants, Intervention, Context, Outcomes (PICO) model framework. Based on these criteria, relevant studies were identified and screened for inclusion. Key information was then extracted from the selected studies by evaluating their methodological quality. To ensure transparency and reproducibility, the methodological quality of each study was assessed using qualitative appraisal criteria, including clarity of research design, coherence between objectives and methodology, rigor in data collection and analysis, and the adequacy of conclusions based on results. These criteria, informed by an established framework, Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP), enabled a consistent evaluation of the internal validity and applicability of the findings. During this process, it became evident that a comprehensive approach to PBL requires a phased analysis due to its complexity and multilayered structure, as noted by Thomas and Harden [31]. As a result, the focus of this review was narrowed to the implementation aspect, allowing for a more in-depth and structured exploration while laying the groundwork for future research on other aspects of PBL.

In the second stage, a qualitative synthesis of the selected studies is conducted through a directed content analysis [32] guided by the framework proposed in this study. The findings are synthesized by identifying patterns, trends, and significant differences, which are then connected to the research questions [33]. Finally, conclusions are drawn regarding the implementation and effectiveness of PBL, assessing its impact on learning outcomes. Additionally, recommendations are provided for future research to explore other factors that influence its application, ensuring a more comprehensive understanding of its challenges and benefits. A qualitative assessment of the research questions was also conducted during the study design phase to ensure that they were analytically grounded and methodologically viable. Their focus on implementation patterns, conceptual fidelity, and perceived effectiveness reflects a deliberate alignment with the epistemological foundations of qualitative inquiry.

2.1.1. Stage 1. Definition of Objectives and Search Strategy Design/Criteria for Systematic Review

In the initial stage of the study, a foundational framework is established to ensure clarity and methodological rigor throughout the research process. This begins with defining the study’s primary objective, formulating precise research questions, and establishing clear inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine the relevance and eligibility of studies for review. Following this, a comprehensive search strategy is designed, involving the identification of appropriate databases and the selection of key search terms tailored to capture the scope of the investigation. To uphold the validity and consistency of the methodology, the entire process adheres to the PRISMA guidelines.

The initial search was conducted using two different databases, WOS and SCOPUS, with the aim of identifying eligible studies that met the inclusion criteria. The search was carried out between May and June 2024, employing the combination of terms “Project-Based Learning” and “implementation”, which yielded a total of 1844 documents in SCOPUS and 26,214 in WOS.

The next step was to refine the set by using the Boolean operators AND and OR in combination with the descriptors “intervention”, “practice”, “design”, “model”, among others. These searches showed an extensive amount of scientific productions and, thanks to this initial phase, it was possible to obtain an overview of the object of study, the existing models in the literature on project-based learning, and the relevance of conducting a systematic review.

The final systematic search was concluded at the end of June, using a 10-year search window (from 2015 to 2024, inclusive) and only English-language articles. This search yielded a total of 17,761 results in WOS and 876 in SCOPUS, with a final filter applied being “students”. The final combination of terms used was as follows:

((project based learning) AND (intervention OR implementation OR practice) AND (model OR design OR principles OR dimensions OR evaluation OR assessment OR reflection))

The new search returned a total of 1072 documents in WOS and 184 in SCOPUS. The inclusion and exclusion criteria used are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria according to PICO model.

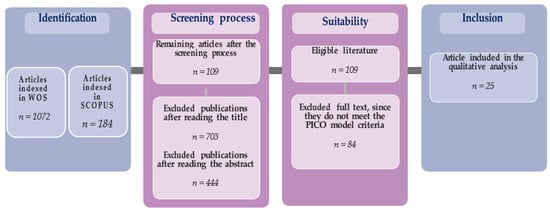

To minimize individual biases, both authors participated in all three phases of the screening and selection of the studies [35]. The first screening was based on titles, by which n= 703 were discarded (n = 593 in WOS, and n= 110 in SCOPUS) as they were deemed irrelevant to the study’s focus, resulting in a total of 479 in WOS and 74 in SCOPUS. Upon the abstract review, n= 444 did not meet the inclusion criteria, leaving a final sample of n = 109 (n= 74 in WOS and n = 35 in SCOPUS). Finally, the full-text screening was carried out, yielding a total of n = 5 studies in SCOPUS and n = 20 in WOS, with n = 54 papers excluded in WOS and n = 30 in SCOPUS, for not meeting certain criteria that had not been identified in the earlier phases of the screening. As a result, n = 25 articles were included in the systematic review (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Planning, identification, and eligibility process workflow.

A closer examination of these 25 selected studies revealed that while many of them addressed the core components and implementation strategies of PBL, several also discussed broader elements [36] such as cognitive development and socio-emotional learning [16]. Although these dimensions were deemed valuable, they extended beyond the scope of the current review. To maintain analytical focus and methodological rigor, the decision was made to narrow the scope exclusively to the implementation of PBL. This approach allows for a more in-depth and structured analysis of how PBL is operationalized in educational practice, while acknowledging the need for future studies to address other interrelated components.

To ensure the level of consensus in the screening phase, the reviewers (the authors of this article) were trained. Initially, 20 randomly selected articles were analyzed to assess agreement levels. Disagreements were resolved through discussion until consensus was achieved. This process was repeated until an adequate agreement level was reached (Cohen’s Kappa > 0.8). Once reviewer training concluded, all articles were screened. Consensus articles were included in the final selection, while those without consensus were discussed for potential inclusion.

The same procedure was followed for the second phase of the study. Reviewer training involved randomly selecting five articles, assessing consensus, and discussing disagreements. The level of consensus was adequate (Cohen’s Kappa > 0.8), so the process was not repeated. Finally, reviewers independently categorized the articles, and the final categorization included articles where both reviewers agreed.

2.1.2. Stage 2. Direct Content Analysis

In this phase, a direct content analysis of the selected models was conducted [32], in order to evaluate the implementation and effectiveness of PBL [8,10,11]. It first focused on the general characteristics of the selected studies, highlighting trends in research activity, predominant methodologies, and the geographical distribution of contributions. Additionally, core procedural components and key methodological practices, including task design, scaffolding, collaboration, research, problem-solving, and assessment, were explored. Further analysis identified critical gaps and imbalances in PBL execution, such as the lack of structured implementation stages, insufficient institutional support, and disparities in resource accessibility. These findings underscore the need for more standardized frameworks to enhance the depth, consistency, and scalability of PBL, ensuring alignment with its foundational principles and the promotion of meaningful learning experiences.

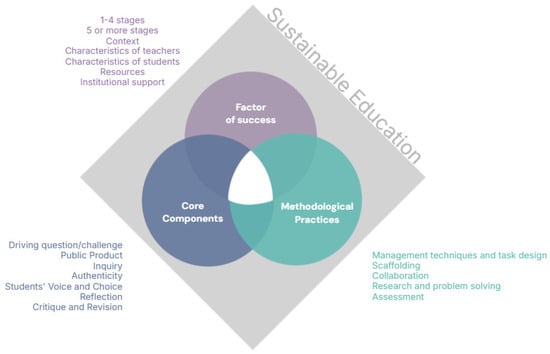

Figure 2 illustrates the analytical framework used in this review, integrating the three key dimensions examined: core components, methodological practices, and contextual success factors. These categories emerged from a systematic content analysis of the selected studies and provided the structure for organizing and interpreting findings in relation to the search questions. The square background represents the overarching framework of sustainable education, emphasizing the integration of these pedagogical elements into a model aligned with SDG 4 and UNESCO’s Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) agenda.

Figure 2.

Analytical framework for PBL dimensions within sustainability-oriented education model.

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of Selected Models

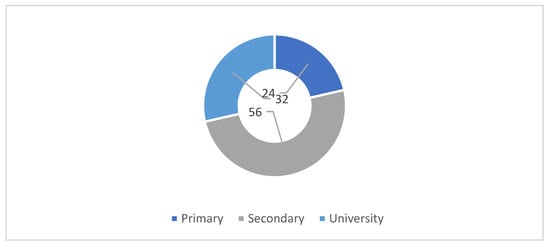

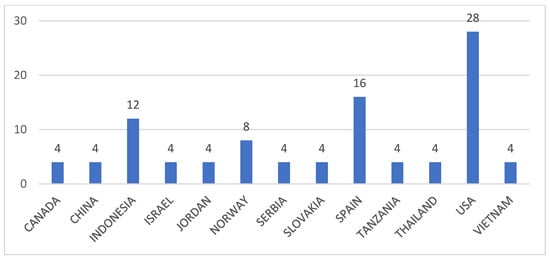

The selected studies identify several noteworthy trends related to PBL. Scientific outputs on PBL have shown a steady increase over the past decade, with 2022 and 2023 showing the highest research activity compared to previous years, as illustrated in Table 2. This trend seems to be maintained in 2024, the year of the study. As 2024 was still ongoing, it was possible that the number of publications would continue to rise. In recent years, most studies have focused on secondary and tertiary education (Figure 3), with a predominant use of quantitative methodologies, whereas research on PBL in early childhood and primary education remains scarce. Additionally, the United States and Spain stand out as leading countries in PBL research, with Indonesia also showing a growing interest in the field (Figure 4).

Table 2.

Models chosen following systematic review.

Figure 3.

Educational stages addressed in PBL studies.

Figure 4.

Country distribution of PBL research.

3.2. Overview of Research Questions

3.2.1. RQ1. How Are the Core Elements of PBL Being Integrated into Educational Institutions According to the Scientific Literature?

To address RQ 1, this section examines the adherence of studies to core PBL principles. These principles, identified by experts as pillars of PBL [8], include the driving question or challenge, public product, inquiry, authenticity, students’ voice and choice, reflection, and critique and revision (Table 3). The success of PBL depends on the correct implementation of these fundamental components, which ensure the authenticity and effectiveness of the approach. By analyzing the presence and integration of these elements in the reviewed studies, we evaluate whether these components are adequately incorporated and how they influence the learning experience.

Table 3.

Core components, categories, and sources.

As shown in Table 3, the inclusion rates across studies reveal significant variability: public product is the most consistently present component (100%), followed by authenticity (92%), driving question (88%), and inquiry (88%). Other essential elements, such as students’ voice and choice (76%), and critique and revision (76%), show moderate presence, while reflection appears in only 68% of cases. These findings provide a nuanced understanding of the extent to which core PBL principles are integrated into educational practices (RQ1). Although the high percentage of inclusion of some components shows the strengths of PBL implementation, such as public presentations of projects, alignment with the real world, and the presence of driving questions and inquiry, there are still areas of improvement in terms of reflection, critique and revision, and students’ voice and choice.

When seen in detail, driving questions or challenges often revolved around real-world problems, promoting authentic engagement and problem-solving [37,38,39]. However, in several cases, the formulation of these questions was instructor-led, limiting students’ participation in this foundational stage [40,41] or simply students were not involved in formulating any questions [42,55,61]. In some studies [43,46,53,56], the assigned project poses clear challenges related to the creation of useful digital tools in project management, introducing key concepts such as digitization or mechanical engineering.

The public product was the most consistently implemented component, appearing in 100% of the studies. These products ranged from community presentations [37,38,40,41,42,44,48,50,52,55,56,57] to functional tools and creative outputs [39,43,45,46,47,49,51,53,54,58,59,60,61].

Inquiry was present in 88% of the studies, underscoring its importance in fostering research and critical thinking. Students engaged in activities like data collection [37,51,53,57,60,61], analysis [38,39,40,41,53,60], hypothesis testing [39], and problem-solving [38,43,44,45,46,47,54,59,60,61], in some cases ending up in innovative solutions. Some inquiries were structured through tools like empathy maps and concept diagrams and future scenarios design [48,49,52]. However, in [58], the main research focus was practical applicability rather than deep exploration of data.

Authenticity was identified in 92% of the studies, indicating its strong integration into PBL. Projects often addressed real-world issues, such as environmental sustainability, engineering challenges, or community needs. Most studies ground projects into real-world contexts, except for [40] (weak contextualization) and [47], which overlooks cultural or socio-economic issues, failing to enrich the educational experience.

Students’ voice and choice appeared in 76% of the studies, suggesting a moderate level of integration. In these cases, students had opportunities to make decisions about project topics, methods, or outputs. In some studies, students had autonomy in structuring projects, addressing sustainability [51], economy [38], final product creation [40,41], students’ roles [44], strategies and tools [45], design and implementation of projects [50], and approaches and solutions within teams [58], which ultimately fostered creativity and ownership. Others, however, highlighted students’ freedom to define the characteristics of their products within certain constraints [56]. Nevertheless, significant gaps were noted, as many projects remained predominantly teacher-directed [47,49,52,53,54,57].

As for reflection, it was included in 68% of the studies analyzed [37,38,39,41,43,45,46,48,50,51,52,55,56,57,58,59,60]. In these cases, it was primarily implemented in the final stages of the project, serving as a retrospective activity rather than an ongoing process. In contrast, studies where reflection was absent [40,42,44,47,49,53,54,61] did not provide students with opportunities to critically evaluate their learning processes or refine their approaches.

Critique and revision were implemented in 76% of the studies [37,38,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,51,53,54,55,56,58,59,61], typically through peer feedback and teacher reviews. Meanwhile, mentor guidance provided expert insights [47,48,49,51,53], ensuring that projects meet academic and professional standards.

These findings suggest that while most studies succeed in ensuring the visibility of PBL through public products and authentic tasks, key reflective and metacognitive practices are frequently neglected. The low inclusion rate of reflection (68%) and the moderate presence of students’ voice and choice (76%) raise concerns about how deeply learners are engaged in self-regulated learning and collaborative participation within projects. Their inconsistent application suggests that while many projects claim to be PBL, they may in fact fall short in realizing its full transformative potential.

Figure 5 presents the frequency of inclusion for each core component, methodological practice, and contextual success factor identified in the reviewed studies. This comparative view highlights areas of strength and underrepresentation in current PBL implementation.

Figure 5.

Percentage of studies in which each core component (blue), methodological practice (green), and contextual success factor (purple) of PBL was identified.

3.2.2. RQ2. Is PBL Truly Being Conducted When It Is Claimed to Be?

RQ2 examines whether PBL is truly implemented as intended. The findings reveal variations in how key elements, such as task design, scaffolding, collaboration, research, and assessment, are implemented across the reviewed studies. By reviewing the literature, this section aims to analyze these discrepancies, identify patterns in current practices, and assess the extent to which claimed PBL implementations align with its fundamental principles.

With regard to key methodological practices, out of the 25 studies analyzed, only 6 studies (24%) incorporated all suggested methodological components, indicating that full adherence to PBL frameworks remains rare. Below is a detailed breakdown of how categories are incorporated across various studies (Table 4).

Table 4.

Methodological practices layer, categories, and sources.

As shown in Table 4, only 44% of the studies include authentic task design and management strategies. However, this percentage increases significantly for collaboration (80%), scaffolding (84%), and research and problem-solving, as well as assessment, which both exhibit a 92% inclusion rate across the studies. Results show that studies [37,38,39,40,42,43,44,45,47,48,56] include detailed task designs, promoting creativity and technical skills. However, other studies, such as [46,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,57,58,59,60,61], fail to go beyond structured, pre-defined activities. In some cases, though students collaborate to do tasks, there is no explicit mention of the use of project management techniques so that students can plan and monitor their progress.

Scaffolding, with an inclusion rate of 84% among the studies analyzed, is primarily provided in [37,38,39,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61] through teacher facilitation, where guidance was tailored to students’ needs. This support varies in implementation: some teachers effectively use questioning techniques to promote deeper thinking, while others concentrate on procedural assistance.

Group work was a central component of most projects [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,48,49,51,52,55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. However, the quality of collaboration and discourse among students varied significantly. In certain projects, teachers and students reported employing strategies such as flexible grouping, student-led discussions, and peer feedback to enhance teamwork [37,38,46,48,51,59,60]. Students were encouraged to take responsibility for their collaborative efforts, with teamwork facilitated through the assignment of specific roles and tasks [43,52,55]. Additionally, students applied problem-solving methods to navigate uncertainties [44,45,57,58], which, in some cases, fostered self-confidence, creativity, and group cohesion [56,61].

Research and problem-solving are integral components of PBL, with various studies demonstrating how these skills are embedded within project activities [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. Structured activities explicitly encouraged inquiry and problem-solving in [40,52], yet the level of rigor in data interpretation and research processes often varied. Projects frequently promoted the application of critical analysis and problem-solving skills [41,42,44,45,46,59], with some designs integrating concepts across multiple courses to deepen inquiry-based learning [56]. Conversely, though inquiry was promoted, strategies for teaching advanced problem-solving techniques remained largely unexplored in some studies [37,51,53].

As for assessment, though present in most articles [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,55,56,57,58,60,61], there is a noticeable lack of balance between both formative and summative methods. In some cases, assessments were comprehensive, incorporating self-evaluation, peer feedback, and teacher-driven rubrics [37]. However, some studies focused more heavily on summative approaches, with less emphasis on formative assessment during project development [54,59].

Although assessment and inquiry are robustly represented, task management and project design strategies are among the most frequently overlooked components, appearing in fewer than half of the studies (44%). This signals a significant gap in the structural scaffolding required for students to effectively plan, execute, and reflect on their work, potentially limiting PBL’s depth and sustainability in real-world classroom contexts.

3.2.3. RQ3. What Are the Critical Gaps or Imbalances in the Implementation of PBL, and How Might These Be Addressed to Better Support Knowledge Acquisition and Competency Development?

To address RQ3, which focuses on identifying the critical gaps and success factors in PBL implementation to ensure effective knowledge acquisition and competency development (Table 5), this section analyses both the primary challenges and key success factors in PBL.

Table 5.

Factors of success layer, categories, and sources.

The analysis of success factors in PBL implementation reveals notable variations across different aspects. Regarding the structure of PBL stages, 40% of the studies [37,38,42,43,44,47,52,54,55,59] implemented projects with 1–4 stages, while 48% [40,41,45,46,48,49,50,51,53,57,58,60] followed a more extended process with five or more stages, suggesting that nearly half of the cases employed a more comprehensive approach to project execution.

The context in which PBL is applied was considered in 96% of the studies [37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61] except [43]. However, other key factors appear to be significantly underrepresented. Teacher characteristics were only analyzed in 20% of the studies [37,41,46,51,59], highlighting a potential gap in examining how educator experience, training, and facilitation skills impact PBL outcomes. Similarly, student characteristics were considered in only 32% of the cases [41,48,49,51,52,59,60,61], meaning that aspects such as student autonomy, prior knowledge, and engagement levels are often overlooked.

In terms of resources, 64% of studies [37,38,39,41,46,49,51,52,53,55,56,57,58,59,60,61] acknowledged their importance, reflecting that access to materials, technology, and time allocation is a crucial determinant in PBL success. However, institutional support was examined in only 20% of the studies [37,42,51,53,55], suggesting that administrative backing, curriculum alignment, and policy frameworks are often underexplored in PBL research.

3.2.4. RQ4. How Do the Identified Implementation Patterns Influence Learning Outcomes and the Perceptions of PBL’s Effectiveness Across Diverse and Sustainable Learning Contexts?

The findings for RQ4, which examines how the elements explored in RQ1, RQ2, and RQ3 influence learning outcomes and stakeholder perceptions of PBL, are derived from an integrated analysis of the previous research questions. Specifically, RQ1 provided insights into how PBL is conceptualized and designed across diverse contexts, highlighting variations in project structure, teacher guidance, and learner autonomy. RQ2 explored the methodological strategies used to assess PBL’s effectiveness, showing how these align, or fail to align, with desired competencies such as collaboration, creativity, and interdisciplinary thinking. RQ3, in turn, focused on implementation challenges, revealing critical enabling conditions such as project management structures, peer interaction dynamics, and institutional support.

Together, these findings underscore the complex interplay of cognitive, social, procedural, and contextual factors that shape the effectiveness of PBL. To further deepen this understanding, and in alignment with a focus on sustainable development, a cross-sectional analysis was conducted to classify the 25 reviewed studies according to the sustainability dimensions addressed. Eleven dimensions were identified to capture both traditional sustainability pillars (environmental, economic, scientific, institutional, or health-related) and transversal educational competencies (social, cognitive, emotional, communicative, technical, cultural).

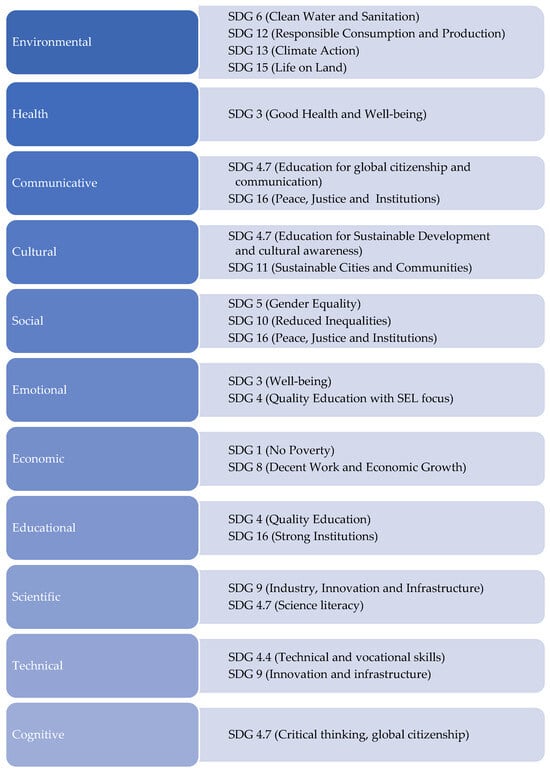

To further contextualize the relevance of the sustainability dimensions identified in this review, each category was mapped against the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [62,63] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Sustainability category and related SDGs.

As shown in Figure 6, this alignment illustrates the diverse ways in which PBL practices can contribute to global sustainability agendas. For example, environmental dimensions found in several studies relate directly to SDG 6 (Clean Water), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption), SDG 13 (Climate Action), and SDG 15 (Life on Land). Similarly, projects emphasizing health-related aspects support SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), while economic and technical dimensions align with SDG 8 (Decent Work) and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure).

Notably, social, cultural, emotional, and communicative dimensions correspond to SDG 4.7, which calls for education that promotes global citizenship, equity, inclusion, and intercultural understanding. This alignment reinforces the potential of PBL not only to enhance disciplinary learning but also to contribute meaningfully to the development of the competencies and values needed for sustainable societies, as envisioned by UNESCO and the 2030 Agenda [63].

In order to provide a clearer overview of how sustainability dimensions are distributed across the selected studies, Table 6 presents each category, the number and percentage of studies addressing it, and the corresponding sources. This structured breakdown allows for the identification of patterns in how project-based learning (PBL) contributes to different aspects of sustainable development, both in terms of disciplinary focus and broader societal impact.

Table 6.

Sustainable layer, categories, and sources.

The results show a marked dominance of social and institutional sustainability dimensions (40% each), indicating that many PBL studies emphasize collaborative learning, equity, and institutional transformation. This aligns with the goals of SDG 4 promoted by UNESCO [62], which advocate for inclusive and equitable education that fosters sustainable communities and institutions.

Meanwhile, environmental, technical, and cognitive dimensions were addressed in 28% of the studies, reflecting the increasing inclusion of STEM/STEAM-focused projects aimed at enhancing technological skills and environmental awareness, two core elements of education for sustainable futures. These findings underscore the multidimensionality of sustainability and reinforce PBL’s role in developing critical competencies for 21st century challenges. Less represented were the economic (20%), scientific (12%), and cultural (8%) dimensions, despite their relevance in global sustainability frameworks. Particularly underrepresented were the health, emotional, and communicative dimensions (each only 4%), which calls for more holistic and inclusive models of PBL that integrate well-being, empathy, and interpersonal skills.

4. Discussion

The implementation of project-based learning has proven to be an effective methodology for fostering critical thinking, collaboration, and meaningful learning [1,6,64]. However, the results of this study reveal significant variability in how PBL is executed across different educational contexts.

The findings suggest that while PBL is widely recognized for its potential to foster engagement, creativity, and real-world problem-solving [1,6,8,64], its implementation remains inconsistent [23]. One of the key takeaways from this study is the discrepancy between theoretical models of PBL and their practical application in educational settings [36]. Although essential elements such as the driving question and public product are consistently integrated, the depth of student involvement and the extent of reflective practices appear to vary significantly across studies.

A particularly revealing aspect of the data is the degree to which students are actively engaged in formulating the driving question. While this element serves as the foundation for inquiry and problem-solving [9], in many cases, it is primarily instructor-led rather than student-generated. This raises concerns about whether students are truly empowered to shape their learning experiences or if they are merely executing pre-designed tasks. A more participatory approach, where students have greater agency in identifying and defining the problem, could enhance engagement and promote a deeper sense of ownership over the learning process [65]. Similarly, while the public product is widely implemented and serves as a key motivation for students, its long-term impact is less frequently considered [23]. Many studies demonstrate how students produce tangible outputs such as presentations, prototypes, and creative works, yet fewer discuss whether these products contribute to sustained learning beyond the project itself. This raises questions about the extent to which PBL fosters lasting competencies versus simply culminating in a final product without curricular alignment or deeper cognitive and metacognitive processing [24].

The role of inquiry within PBL also presents an interesting contrast. Some studies illustrate its potential to promote critical thinking through research, data analysis, and hypothesis testing [17]. However, the structure and depth of inquiry differ significantly. In some cases, inquiry is scaffolded in ways that encourage independent exploration, while in others, it is overly structured, limiting students’ ability to engage in self-directed learning [9]. This suggests that while inquiry is a foundational element of PBL, its implementation requires careful balancing between guidance and autonomy to ensure that students are both supported and challenged [66]. Another area to consider is the integration of authenticity into PBL projects. Although many studies align projects with real-world challenges [26], few of them fall short in contextualizing these challenges within students’ cultural or socio-economic backgrounds. Without this connection, projects may feel abstract rather than personally meaningful, potentially reducing student motivation and engagement [20]. A stronger emphasis on locally relevant issues could enhance the depth of learning and make PBL experiences more impactful.

One of the most significant gaps identified is the role of student autonomy. While some projects allow students to make meaningful decisions about their work, such as selecting topics, structuring project plans, or defining deliverables, others remain predominantly teacher-directed [23]. This undermines one of the fundamental principles of PBL: fostering self-regulation and learner independence [21]. If students are not actively involved in making key decisions, they may struggle to develop the problem-solving and decision-making skills that PBL aims to cultivate.

Reflection, a critical yet often underutilized component of PBL, is another area requiring further attention [67]. Although some studies incorporate reflection at various stages, in many cases, it is confined to the final phase of the project, serving as a retrospective rather than an ongoing or feedforward practice. This limits students’ ability to refine their understanding throughout the process, as students do not only learn from experience, but also from reflecting on it [5]. Embedding reflection at multiple points could encourage deeper cognitive engagement and allow students to continually assess and improve their work [25].

Similarly, critique and revision processes, though present, often lack the progressive depth required to maximize their effectiveness. Many studies incorporate feedback cycles through peer and teacher reviews, yet these cycles are not always structured in ways that allow for sustained improvement [66]. A more deliberate integration of formative assessment mechanisms could help students refine their thinking and enhance the quality of their final outputs.

Another area to consider is the integration of interdisciplinarity in PBL, which, although present in many projects, has not been consistently recognized as a fundamental component. Despite its potential to foster holistic thinking and inclusion, interdisciplinarity has largely been treated as an additional feature rather than a core pedagogical element of PBL. This omission limits the depth of learning connections students can make across disciplines, which is a key factor in preparing them for complex, real-world challenges [68]. The recognition of interdisciplinarity as an essential element rather than a peripheral feature represents a novel contribution of this study, offering a framework for rethinking how PBL can connect diverse areas of knowledge to create deeper and more socially relevant learning experiences. This also implies the need to redefine the distribution of subject areas within educational centers, in order to adopt a transdisciplinary approach. Taken together, these insights underscore the need for greater alignment between the theoretical foundations of PBL and its practical execution. The inconsistencies observed suggest that while PBL is often claimed to be implemented, its application may not always fully adhere to its core principles. Addressing these gaps, particularly in student agency, inquiry depth, reflective practice, and interdisciplinarity could strengthen PBL’s effectiveness and ensure that it delivers on its promise of fostering deep, meaningful learning experiences.

In addressing RQ2 (Is PBL truly being conducted when it is claimed to be?), the findings suggest that while many studies claim to implement PBL, inconsistencies in task design, scaffolding, collaboration, inquiry, and assessment indicate that it is not always fully realized as intended. These discrepancies raise concerns about whether PBL is genuinely applied as a student-centered, inquiry-driven methodology or if, in some cases, it is being implemented in a more superficial or teacher-directed manner.

One of the defining characteristics of PBL is the integration of tasks that promote real-world engagement and independent learning [8,69]. However, the analysis of task design in the reviewed studies indicates that while some projects encourage creativity and technical skill development, many remain overly structured, with pre-defined activities that restrict student autonomy. In some cases, project management strategies are absent. This suggests that, at times, project-based activities are implemented without the necessary degree of student agency, limiting the methodology’s transformative potential.

Regarding scaffolding, while most studies demonstrate the presence of teacher-facilitated guidance, the depth and nature of scaffolding vary considerably. Some educators employ dynamic strategies that adapt to students’ needs, promoting deeper thinking and problem-solving skills, while others focus primarily on procedural support, limiting opportunities for cognitive growth. The inconsistency in scaffolding approaches suggests that PBL is not always fully realized as an inquiry-driven learning process but is sometimes reduced to guided task completion rather than an iterative, student-centered experience.

Collaboration is a cornerstone of PBL, yet the extent to which it is meaningfully integrated into projects differs among the reviewed studies. However, not addressing group dynamics or problem-solving strategies results in uneven contributions and, at times, individual work replacing collaboration [23]. The lack of structured approaches to teamwork in certain cases raises concerns about whether these projects genuinely embody the collaborative principles central to PBL or if they merely incorporate surface-level group work.

Inquiry and problem-solving are also fundamental to PBL [17]. The analysis shows that while many projects encourage students to engage in research, the extent of inquiry varies significantly. Some studies emphasize structured research approaches, in others, problem-solving is heavily teacher-controlled, limiting students’ ability to develop independent inquiry skills. In these cases, students often follow teacher-led steps and instructions that resemble traditional methodologies, where the learning path follows an instruction-to-investigation model rather than a challenge-to-inquiry transformation. This not only restricts autonomy or limits students’ ability to make meaningful decisions about their learning, but also undermines the essence of PBL by compromising its key principles, such as student agency, authenticity, and deep engagement, where the challenge drives the learning, the investigation is fueled by students’ curiosity, and there is room to explore, fail, iterate, and make meaningful decisions throughout the process. These practices prompt questions about whether students in these projects are truly engaging in authentic problem-based learning or merely go along with structured assignments under the guise of inquiry.

Assessment in PBL should encompass both formative and summative strategies to support continuous learning and reflection [67]. However, the reviewed studies reveal an imbalance between these approaches. Many studies focus on evaluating cognitive and technical skills while overlooking soft skills such as communication, leadership, and empathy, critical competencies in real-world problem-solving. The absence of comprehensive formative assessment structures in certain cases indicates that PBL is not always implemented in a way that maximizes student learning and development.

The analysis highlights several critical gaps in PBL implementation that impact knowledge acquisition and competency development (RQ3). One key factor is the number of implementation stages, as projects with fewer stages tend to prioritize task completion over structured reflection and iterative feedback, limiting opportunities for deeper learning and skill. In contrast, studies incorporating multiple stages demonstrate better integration of reflection, scaffolding, and assessment, leading to more engaged and self-directed learners [11]. Another significant aspect is the role of contextualization. Studies that provide rich contextual details, such as student demographics, faculty expertise, and institutional settings, show stronger alignment between student needs and project goals [22]. When PBL is adapted to the specific educational environment, students experience higher engagement, motivation, and real-world applicability of their learning [26]. Faculty qualifications also contribute to PBL success, as experienced educators are better equipped to implement effective scaffolding and formative assessment strategies [21]. Additionally, access to resources remains a challenge, with disparities in technological tools and institutional support creating uneven learning experiences [9]. While some projects benefit from advanced tools and well-equipped environments, others struggle due to a lack of digital resources and infrastructure, hindering project scalability and student participation [36]. Studies showcasing well-established institutional support highlight benefits regarding access to technology, research databases, and interdisciplinary resources. Another asset of administrative backing is curricular integration and alignment with institutional objectives.

The core elements and implementation patterns of PBL directly impact learning outcomes and perceptions of its effectiveness (RQ4). Well-structured projects with clear stages, reflection, and feedback enhance student engagement, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills [9,64]. In contrast, inconsistencies in task design, scaffolding, and assessment reduce opportunities for deep learning and self-regulation [23]. However, the gaps observed in institutional support and resource accessibility create variability in PBL’s effectiveness [26], underscoring the need for consistent implementation frameworks to maximize its impact. A lack of institutional support can hinder teachers’ ability to collaborate, access to necessary materials, and time allocation for planning and assessment [1]. This often leads to superficial implementation, where the core principles of PBL are not fully realized. Effective PBL implementation typically requires substantial coordination efforts, including cross-disciplinary planning, continuous formative assessment design, and alignment with curricular standards. Without formal structures that support this workload, such as scheduled collaboration time, professional development, and administrative backing, teachers may experience burnout or revert to traditional methods, reducing the transformative potential of PBL for student learning.

This may also help explain why, despite its frequent mention in the literature, interdisciplinarity is not consistently considered a core component of PBL. While theoretically aligned with PBL’s philosophy, interdisciplinary work requires significant logistical coordination and institutional support, elements that are often lacking in real-world educational contexts [68]. As a result, schools may adopt a more discipline-specific approach to PBL that is easier to manage within existing constraints, which can diminish the richness interdisciplinarity brings to PBL. Consequently, students may miss opportunities to make meaningful connections across subject areas, limiting their ability to approach real-world problems from multiple perspectives. The holistic nature of learning, a hallmark of well-implemented PBL, is therefore compromised, reducing students’ capacity to transfer knowledge and engage inquiry that mirrors complex societal challenges.

These implementation barriers are also reflected in the types of sustainability dimensions most commonly addressed in PBL research and practice. As shown in our analysis, PBL tends to emphasize social and institutional/educational dimensions, such as collaboration, equity, and school-level innovation, likely because these are more feasible to implement within existing systems. Environmental, technical, and cognitive dimensions also appear frequently, often through STEM- or STEAM-related projects that prioritize disciplinary integration, design thinking, and real-world problem-solving.

In contrast, affective, health-related, and communicative competencies, which are equally central to the transformative vision of Education for Sustainable Development [62,63], are rarely prioritized in implementation. These underrepresented areas (each appearing in only 4% of studies) often require a pedagogical shift toward well-being, empathy, emotional engagement, and dialog, which in turn depend on institutional cultures that value and support these aims. The lack of time, training, or curriculum flexibility may prevent teachers from addressing these competencies meaningfully, reinforcing a narrow, outcome-driven vision of PBL that misses its broader humanistic potential.

Therefore, the same constraints that limit interdisciplinarity also explain why certain sustainability dimensions are systematically underrepresented in PBL practice. Addressing these systemic issues through better design and structural support, broader definitions of success, a comprehensive step-by-step implementation, and professional development aligned with holistic sustainability goals is essential for realizing the full potential of PBL as a driver of quality education and sustainable development.

The findings discussed above give rise to several important theoretical and managerial implications, which are outlined below.

4.1. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the existing literature by providing a systematic analysis of the gaps between theoretical principles of PBL and their actual implementation in different educational settings. By highlighting the inconsistent application of key elements, particularly student agency, reflection, and inquiry, this work extends existing conceptualizations of PBL beyond its structural components to emphasize deeper pedagogical concerns such as learner empowerment, authentic inquiry, interdisciplinarity, and versatility. This versatility refers to PBL’s adaptability across different educational levels, disciplines, and contexts, enabling it to respond to heterogeneous learner needs and institutional conditions while preserving its core principles.

In doing so, it builds upon and challenges current models, arguing for a redefinition of interdisciplinarity not as a supplementary feature, but as a core element integral to the transformative intent of PBL [68]. This repositioning has important theoretical consequences, especially for advancing frameworks that integrate sustainability, equity, and 21st century competencies into everyday educational practices. Moreover, the study explicitly articulates its originality by synthesizing and critically evaluating how reflective and metacognitive practices are underutilized in practice. It thus invites a reconceptualization of what constitutes “authentic” PBL and underscores the need for a paradigm shift that prioritizes continuous reflection, student-led inquiry, and structural support as foundational, not optional.

4.2. Managerial Implications

From a practical perspective, this research offers valuable insights for school leaders, curriculum designers, and policymakers aiming to foster effective PBL environments. First, it underscores the necessity of institutional support, including ongoing professional development through targeted training, peer mentoring, structured collaboration time, and administrative alignment, to ensure that PBL is implemented with fidelity and depth. Institutions should develop implementation plans that incorporate formative assessment cycles, collaborative planning frameworks, and interdisciplinary coordination mechanisms.

Second, this study emphasizes the importance of scaffolded inquiry and formative feedback, particularly in diverse classroom contexts. In settings with limited resources or varying student readiness levels, scaffolding strategies can be adapted to include peer-led inquiry circles, teacher-guided reflection journals, and differentiated questioning techniques. Feedback mechanisms can include checkpoints with rubrics, peer-review protocols, and iterative revisions supported by coaching. These methods can be scaled flexibly to accommodate different educational realities while preserving the integrity of the PBL model.

Finally, the study reveals that structural and systemic constraints, such as curricular rigidity, policy misalignment, and insufficient teacher training, play a decisive role in limiting the depth and consistency of PBL implementation. These factors must be addressed through institutional and policy reforms that prioritize PBL as a strategic objective, allocate resources for capacity-building, and embed interdisciplinary learning within curricular standards. Addressing these implications holistically can significantly increase the sustainability, equity, and transformative potential of PBL across educational contexts.

5. Conclusions

Over the past decades, PBL has become increasingly prominent in educational practice due to its potential to enhance student engagement and foster essential skills. Yet the wide range of implementation models has brought into question how effectively these practices align with the foundational principles of PBL and whether they consistently achieve the intended learning outcomes.

This study reveals that, although many PBL initiatives demonstrate adherence to foundational elements and incorporate selected implementation strategies, significant inconsistencies persist across educational contexts. These are particularly evident in areas such as student autonomy, depth of inquiry, structured reflection, and formative assessment. While key components are often present at a surface level, limited scaffolding and collaboration undermine the development of self-regulated learning and higher-order thinking skills.

Interdisciplinarity, although frequently acknowledged in theory, is not systematically used to support inclusive and holistic learning, reducing its transformative potential. Furthermore, weaknesses in project structure, contextual relevance, and institutional support continue to negatively impact learning outcomes and stakeholders’ perceptions of PBL’s educational value.

Maximizing PBL’s impact requires greater implementation consistency, institutional backing, and teacher training. Addressing these structural challenges is key to unlocking PBL’s full potential as a meaningful, inclusive, and future-ready learning approach. In addition, the uneven integration of some sustainability dimensions, especially emotional, communicative, and health-related aspects, highlights the need for broader pedagogical frameworks that align PBL with the competencies outlined in SDG 4 and UNESCO’s vision for education for sustainable development. Furthermore, this study offers an original contribution by inviting a reconceptualization of authentic PBL, not by introducing new components, but by emphasizing the need to integrate reflective thinking as an on-going process and to strengthen student-led inquiry as core, sustained practices. It argues that interdisciplinarity should no longer be treated as an auxiliary component, but rather as a transformative core of the model, especially if PBL is to meaningfully integrate competencies related to sustainability, equity, and 21st century challenges. This vision calls for a paradigm shift that positions the versatility of PBL as a key strength in addressing the diversity of educational contexts.

Despite the valuable insights provided, this study has limitations, particularly in assessing PBL’s cognitive and socio-emotional impact. Future research should prioritize longitudinal and mixed-method approaches to investigate how learners internalize, transfer, and sustain knowledge and competencies over time, providing a more holistic view of the learning process and the sustainability of its outcomes across emotional, cognitive, and behavioral domains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S.-G. and S.R.-d.-C.; methodology, R.S.-G. and S.R.-d.-C.; validation, R.S.-G. and S.R.-d.-C.; formal analysis, R.S.-G. and S.R.-d.-C.; investigation, R.S.-G. and S.R.-d.-C.; resources, R.S.-G. and S.R.-d.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S.-G.; writing—review and editing, R.S.-G. and S.R.-d.-C.; visualization, R.S.-G. and S.R.-d.-C.; supervision, R.S.-G. and S.R.-d.-C.; project administration, R.S.-G. and S.R.-d.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PBL | Project-based learning |

| RQ | Research question |

| WOS | Web of Science |

| PICO | Participants, Intervention, Context, Outcomes |

| CASP | Critical Appraisal Skills Programme |

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

| STEAM | Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics |

References

- Sánchez-García, R. Project-Based Learning: Impact on the Acquisition of Content, Competencies and Skills in Primary and Secondary Bilingual Education. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain, March 2022. Available online: https://helvia.uco.es/xmlui/handle/10396/22731 (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Zambrano-Briones, M.A.; Hernández Díaz, A.; Mendoza Bravo, K.L. El aprendizaje basado en proyectos como estrategia didáctica. Rev. Conrado 2022, 18, 172–182. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J. La Construcción de lo Real en el Niño; Crítica: Barcelona, Spain, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Experience and Education; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Gras-Velázquez, A. Project-Based Learning in Second Language Acquisition: Building Communities of Practice in Higher Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Trilling, B.; Fadel, C. 21st Century Skills: Learning for Life in Our Times; Jossey-Bass/Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Larmer, J.; Mergendoller, J.R.; Boss, S. Setting the Standard for Project Based Learning: A Proven Approach to Rigorous Classroom Instruction; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, P.; Saab, N.; Post, L.S.; Admiraal, W. A review of project-based learning in higher education: Student outcomes and measures. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 102, 101586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, B.; Wells, J.; Kingston, S. Transforming Schools Using Project-Based Learning Performance Assessment, and Common Core Standards; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stoller, F.L.; Myers, C.C. Project-Based Learning: A Five-Stage Framework to Guide Language Teachers. In Project-Based Learning in Second Language Acquisition: Building Communities of Practice in Higher Education; Gras-Velázquez, A., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Guan, Y.; Hu, Z. The efficacy of project-based learning in enhancing computational thinking among students: A meta-analysis of 31 experiments and quasi-experiments. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 14513–14545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullan, M. The New Meaning of Educational Change, 4th ed.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Hyler, M.E.; Gardner, M. Effective Teacher Professional Development; Learning Policy Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins, G.; McTighe, J. Understanding by Design, 2nd ed.; Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Strobel, J.; van Barneveld, A. When is PBL More Effective? A Meta-synthesis of Meta-analyses Comparing PBL to Conventional Classrooms. Interdiscip. J. Probl.-Based Learn. 2009, 3, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.; Leary, H. A Problem Based Learning Meta Analysis: Differences Across Problem Types, Implementation Types, Disciplines, and Assessment Levels. Interdiscip. J. Probl.-Based Learn. 2009, 3, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.Y.; Yalvac, B.; Capraro, M.M.; Capraro, R.M. In-service Teachers’ Implementation and Understanding of STEM Project Based Learning. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2015, 11, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Skelcher, S.; Gao, F. An investigation of teacher experiences in learning the project-based learning. J. Educ. Learn. 2021, 15, 490–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, R.; Pavón, V. Students’ perceptions on the use of Project-Based Learning in CLIL: Learning outputs and psycho affective considerations. Lat. Am. J. Content Lang. Integr. Learn. 2021, 14, 69–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertmer, P.A.; Simons, K.D. Jumping the PBL Implementation Hurdle: Supporting the Efforts of K–12 Teachers. Interdiscip. J. Probl.-Based Learn. 2006, 1, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, W. Theory to reality: A few issues in implementing problem-based learning. Educ. Tech Res. Dev 2011, 59, 529–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condliffe, B.; Quint, J.; Visher, M.G.; Bangser, M.R.; Drohojowska, S.; Saco, L.; Nelson, E. Project-Based Learning: A Literature Review; MDRC: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shekh-Abed, A. Metacognitive self-knowledge and cognitive skills in project-based learning of high school electronics students. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2024, 50, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigner, M.S. The Use of Project-Based Learning to Scaffold Student Social and Emotional Learning Skill Development, Science Identity, and Science Self-Efficacy. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/7566 (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Flook, L.; Cook-Harvey, C.; Barron, B.; Osher, D. Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2019, 24, 97–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Cajaraville, A.; Reyes-de-Cózar, S.; Navazo-Ostúa, P. SCHEMA: A Process for the Creation and Evaluation of Serious Games—A Systematic Review towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; The Cochrane Collaboration and John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-470-69951-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Revilla, J.; Greca, I.M.; Meneses-Villagrá, J.-Á. Effects of an integrated STEAM approach on the development of competence in primary education students. J. Study Educ. Dev. 2021, 44, 838–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, B.; Catalá-López, F.; Moher, D. La extensión de la declaración PRISMA para revisiones sistemáticas que incorporan metaanálisis en red: PRISMA-NMA. Med. Clínica 2016, 147, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the Synthesis of Evidence: A Critical Review. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2008, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, D.; Oliver, S.; Thomas, J. An Introduction to Systematic Reviews, 2nd ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-de-Cózar, S.; Pérez-Escolar, M.; Navazo, P. Digital Competencies for New Journalistic Work in Media Outlets: A Systematic Review. Media Commun. 2022, 10, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.M.; Arnold, S.R.; Weise, J.; Pellicano, E.; Trollor, J.N. Defining autistic burnout through experts by lived experience: Grounded Delphi method investigating #AutisticBurnout. Autism 2021, 25, 2356–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokotsaki, D.; Menzies, V.; Wiggins, A. Project-based learning: A review of the literature. Improv. Sch. 2016, 19, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dole, S.; Bloom, L.; Kowalske, K. Transforming Pedagogy: Changing Perspectives from Teacher-Centered to Learner-Centered. Interdiscip. J. Probl.-Based Learn. 2016, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia, J.D.; Martínez Soria, V. Creative Project-based learning to boost technology innovation. Tic Rev. Iinnovació Educativa 2017, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, J.; Arshavsky, N.; Glennie, E.; Charles, K.; Rice, O. The Relationship Between Project-Based Learning and Rigor in STEM-Focused High Schools. Interdiscip. J. Probl.-Based Learn. 2017, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahasneh, A.M.; Alwan, A.F. The Effect of Project-Based Learning on Student Teacher Self-efficacy and Achievement. Int. J. Instr. 2018, 11, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culclasure, B.T.; Longest, K.C.; Terry, T.M. Project-Based Learning (Pjbl) in Three Southeastern Public Schools: Academic, Behavioral, and Social-Emotional Outcomes. Interdiscip. J. Probl.-Based Learn. 2019, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.Q.; Tran, T.N.P. Attitudes toward the Use of Project-Based Learning: A Case Study of Vietnamese High School Students. J. Lang. Educ. 2020, 6, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngereja, B.; Hussein, B.; Andersen, B. Does Project-Based Learning (PBL) Promote Student Learning? A Performance Evaluation. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, B.D.; Knežević, J.B.; Maričić, S.M. The influence of project-based learning on student achievement in elementary mathematics education. S. Afr. J. Educ. 2021, 41, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, B. Addressing Collaboration Challenges in Project-Based Learning: The Student’s Perspective. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudjimat, D.A.; Nyoto, A.; Romlie, M. Implementation of Project-Based Learning Model and Workforce Character Development for the 21st Century in Vocational High School. Int. J. Instr. 2021, 14, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwantono, S.; Wulansari, R.E.; Nabawi, R.A.; Safitri, D.; Kiong, T.T. The Effectiveness of Project-Based Learning On 4Cs Skills of Vocational Students in Higher Education. J. Tech. Educ. Train. 2022, 14, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespí, P.; García-Ramos, J.M.; Queiruga-Dios, M. Project-Based Learning (PBL) and Its Impact on the Development of Interpersonal Competences in Higher Education. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 2022, 11, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidergor, H.E. Effects of Innovative Project-Based Learning Model on Students’ Knowledge Acquisition, Cognitive Abilities, and Personal Competences. Interdiscip. J. Probl.-Based Learn. 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botella, A.M.; Ramos, P.R. Teaching Dilemmas and Student Motivation in Project-based Learning in Secondary Education. Interdiscip. J. Probl.-Based Learn. 2022, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, N.; Rodriguez-Meehan, M.; Stork, M.G. This School is Made for Students: Students’ Perspectives on PBL. J. Form. Des. Learn. 2022, 6, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanillas, E. The impact of interdisciplinary Project Based Learning on young learners’ speaking results. Porta Linguarum 2023, 39, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.R.; Marji, M.; Sutadji, E.; Sugandi, M. Integration of STEM project-based learning into 21st century learning and innovation skills (4Cs) in vocational education using SEM model analysis. Hacet. Univ. J. Educ. 2023, 38, 454–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maros, M.; Korenkova, M.; Fila, M.; Levicky, M.; Schoberova, M. Project-based learning and its effectiveness: Evidence from Slovakia. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 4147–4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saimon, M.; Lavicza, Z.; Dana-Picard, T. Enhancing the 4Cs among college students of a communication skills course in Tanzania through a project-based learning model. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 6269–6285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, R.M.; Jazayeri, Y.; Behjat, L.; Potter, M. Design of an Integrated Project-Based Learning Curriculum: Analysis Through Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2023, 66, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Chen, C.; Touitou, I.; Bartz, K.; Schneider, B.; Krajcik, J. Predicting student science achievement using post-unit assessment performances in a coherent high school chemistry project-based learning system. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2023, 60, 724–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-M.; Tu, C.-C. Developing a Project-Based Learning Course Model Combined with the Think–Pair–Share Strategy to Enhance Creative Thinking Skills in Education Students. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]