Social Media Influence: Bridging Pro-Vaccination and Pro-Environmental Behaviors Among Youth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Media as a Medium for Participatory Communication

2.2. Social Media Influence on Environmental Behavior

- Identifying and collaborating with micro- and macro-influencers aligned with both public health and environmental values.

- Tailoring content formats and tones to the communication styles of different audience segments.

- Framing messages around shared experiences, empathy, and aspirational narratives that inspire collective action.

2.3. Bridging Health and Environmental Behaviors

2.4. Conceptual Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

- Exposure to and type of content on social media;

- Influence of opinion leaders and influencers;

- Personal and social experiences;

- Algorithmic amplification;

- Emotional resonance and message framing;

- Social environment and peer influence.

3.2. Research Objectives

- O1.

- Evaluate the influence of exposure to science-based content on social media on public attitudes toward vaccination and pro-environmental behavior.

- O2.

- Investigate the impact of misinformation on social media on vaccine hesitancy and environmental skepticism.

- O3.

- Determine the effectiveness of opinion leaders in promoting vaccine acceptance and environmental responsibility via social media.

- O4.

- Analyze the relationship between financial investments in digital campaigns and public attitudes toward vaccination and sustainability.

- O5.

- Examine the influence of psychosocial factors on health- and environment-related decisions in the digital context.

- O6.

- Evaluate the role of social media algorithms in shaping public opinion on vaccines and environmental issues.

- O7.

- Assess the effectiveness of personalized, emotionally resonant educational content in reducing vaccine hesitancy and ecological apathy.

3.3. Hypotheses Development and Theoretical Justification

3.4. Data Analysis Technique

4. Results

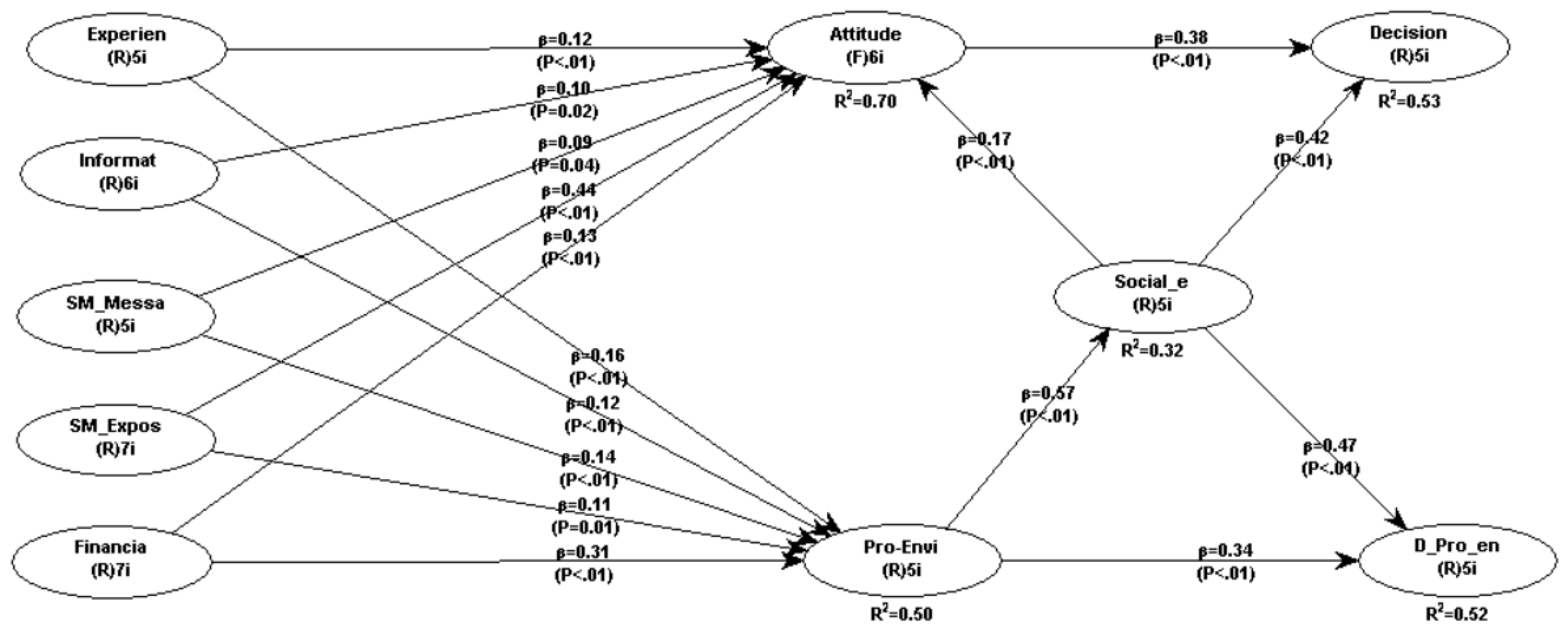

- Previous Experience (β = 0.12; p < 0.01): Previous experiences have a positive influence on attitudes towards vaccines, indicating that both direct and indirect encounters shape individuals’ perceptions.

- Official Sources of Information (β = 0.10; p = 0.02): Official information sources contribute positively to the formation of a favorable attitude towards vaccines, albeit with a relatively modest impact.

- Social Media Messages (β = 0.09; p = 0.04): Social media messages exert a marginal yet significant effect on attitudes, underscoring the impact of online communications on public perceptions.

- Exposure to Social Media (β = 0.44; p < 0.01): Interaction with social media proves to be the most influential factor on attitudes, suggesting that engagement with social platforms can substantially shape public opinion.

- Financial Investments (β = 0.13; p < 0.01): Financial aspects related to vaccination, including perceived costs and resource allocation, substantially affect attitudes.

- Social Environment (β = 0.17; p < 0.01): The social environment plays a crucial role, reflecting how social groups and communities influence the development of attitudes towards vaccination.

- Attitude towards Vaccines (β = 0.38; p < 0.01): A favorable attitude towards vaccines serves as a strong predictor of the vaccination decision, suggesting that positive perceptions enhance the likelihood of choosing to get vaccinated.

- Social Environment (β = 0.42; p < 0.01): The social environment is even more influential than individual attitudes in shaping the vaccination decision, highlighting the importance of social norms and support in the decision-making process.

- Pro-environmental Attitude (R2 = 0.50): The model shows that 50% of the variance in Pro-environmental Attitude is explained by the following predictors:Social Media Messages (β = 0.16; p < 0.01): Emotionally resonant and engaging messages shared via social platforms have a significant influence on pro-environmental attitudes, indicating that storytelling and content framing can shift youth perceptions toward sustainability.

- Exposure to Social Media (β = 0.12; p < 0.01): Frequent interaction with digital content related to environmental topics positively correlates with awareness and concern, highlighting the power of platform engagement in shaping eco-consciousness.

- Financial Investments (β = 0.14; p < 0.01): Investment in digital environmental campaigns positively affects environmental attitudes, confirming that well-funded, targeted messaging enhances user receptivity.

- Official Sources of Information (β = 0.11; p = 0.01): Official environmental communication contributes modestly but significantly to forming pro-environmental beliefs, underlining the importance of institutional trust.

- Previous Experience (β = 0.11; p = 0.01): Personal or indirect involvement in environmental initiatives increases concern and favorable attitudes, suggesting that familiarity enhances emotional investment.

- Financial Factors (again, β = 0.31; p < 0.01): This strong coefficient may reflect the overlap in perception regarding how environmental actions are funded or incentivized, further emphasizing the importance of perceived value and accessibility.

- Pro-environmental Decision (R2 = 0.52): 52% of the variance in Pro-environmental Decision is explained by the following:

- Pro-environmental Attitude (β = 0.34; p < 0.01): As expected, a strong, positive attitude toward environmental issues significantly increases the likelihood of engaging in sustainable behavior, confirming the attitudinal–behavioral link.

- Social Environment (β = 0.47; p < 0.01): The influence of peers, family, and social norms is even more pronounced in environmental decisions than in vaccination choices. This underscores that sustainable behavior is deeply embedded in group identity, shared values, and cultural acceptance.

Cross-Cutting Insights

5. Discussion

- Empathetic storytelling to drive emotional connection

- Evidence-based messaging adapted to the audience’s values and concerns

- Cultural and contextual tailoring to different demographic and psychographic segments

- Collaboration with digital influencers and peer leaders to normalize desired behaviors

- Algorithmic tools to prioritize verified content and reduce the spread of misinformation

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

7. Conclusions

8. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vosoughi, S.; Roy, D.; Aral, S. The spread of true and false news online. Science 2018, 359, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachmad, Y.E. Social Media Impact Theory; Academia: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cinelli, M.; De Francisci Morales, G.; Galeazzi, A.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Starnini, M. The echo chamber effect on social media. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023301118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, C.R.; Sloan, R.; Giedt, J.Z. Defining, measuring, and modeling accruals: A guide for researchers. Rev. Account. Stud. 2018, 23, 827–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baym, N.K. Personal Connections in the Digital Age; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Parveen, F.; Jaafar, N.I.; Ainin, S. Social media usage and organizational performance: Reflections of Malaysian social media managers. Telemat. Inform. 2015, 32, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. The early bird catches the news: Nine things you should know about micro-blogging. Bus. Horizons 2011, 54, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Nirula, A.; Heller, B.; Gottlieb, R.L.; Boscia, J.; Morris, J.; Huhn, G.; Cardona, J.; Mocherla, B.; Stosor, V.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody LY-CoV555 in outpatients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y.; He, T.; Mueller, T.; Smola, A.; et al. Resnest: Splitattention networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–20 June 2022; pp. 2736–2746. [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein, C. Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guess, A.M.; Lerner, M.; Lyons, B.; Montgomery, J.M.; Nyhan, B.; Reifler, J.; Sircar, N. A digital media literacy intervention increases discernment between mainstream and false news in the United States and India. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 15536–15545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.L.; Wiysonge, C. Social media and vaccine hesitancy. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e004206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessi, A.; Zollo, F.; Del Vicario, M.; Puliga, M.; Scala, A.; Caldarelli, G.; Uzzi, B.; Quattrociocchi, W. Users Polarization on Facebook and Youtube. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; McPhetres, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.G.; Rand, D.G. Fighting COVID-19 misinformation on social media: Experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy-nudge intervention. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, C.; Akos, P.; Domina, T.; Young, Z. Student-to-school counselor ratios: A meta-analytic review of the evidence. J. Couns. Dev. 2021, 99, 418428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M.J.; Harris, E.A.; Fielding, K.S. The psychological roots of anti-vaccination attitudes: A 24-nation investigation. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schivinski, B.; Dabrowski, D. The effect of social media communication on consumer perceptions of brands. J. Mark. Commun. 2016, 22, 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bavel, J.J.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.S.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Cikara, M.; Crockett, M.J.; Crum, A.J.; Douglas, K.M.; Druckman, J.N.; et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsch, C.; Korn, L.; Sprengholz, P.; Felgendreff, L.; Eitze, S.; Schmid, P.; Böhm, R. Social and behavioral consequences of mask policies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 21851–21853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. Accuracy prompts are a replicable and generalizable approach for reducing the spread of misinformation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowsky, S.; Cook, J.; Ecker, U.; Albarracin, D.; Kendeou, P.; Newman, E.J.; Pennycook, G.; Porter, E.; Rand, D.; Zaragoza, M.S.; et al. The Debunking Handbook 2020; Center for Climate Change Communication: Fairfax, VA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. COVID19 Weekly Epidemiological Update, 43rd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, J.B.; Hawthorne, J.; Perreault, M.F.; Park, E.H.; Hode, M.G.; Halliwell, M.R.; McGowen, S.E.T.; Davis, R.; Vaid, S.; McElderry, J.A.; et al. Social media and disasters: A functional framework for social media use in disaster planning, response, and research. Disasters 2015, 39, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roozenbeek, J.; Schneider, C.R.; Dryhurst, S.; Kerr, J.; Freeman, A.L.J.; Recchia, G.; van der Bles, A.M.; van der Linden, S. Susceptibility to misinformation about COVID-19 around the world. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 201199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, R.; Dana, T.; Buckley, D.I.; Selph, S.; Fu, R.; Totten, A.M. Epidemiology of and risk factors for coronavirus infection in health care workers: A living rapid review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 120136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsch, C.; Böhm, R.; Korn, L.; Holtmann, C. On the benefits of explaining herd immunity in vaccine advocacy. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2017, 1, 0056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, S.; Leiserowitz, A.; Rosenthal, S.; Maibach, E. Inoculating the Public against Misinformation about Climate Change. Glob. Challenges 2017, 1, 1600008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broniatowski, D.A.; Jamison, A.M.; Qi, S.; AlKulaib, L.; Chen, T.; Benton, A.; Quinn, S.C.; Dredze, M. Weaponized health communication: Twitter bots and Russian trolls amplify the vaccine debate. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 1378–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luttrell, R. Social Media: How to Engage, Share, and Connect; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, ML, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S.; Lavergne, V.; Skinner, A.M.; GonzalesLuna, A.J.; Garey, K.W.; Kelly, C.P.; Wilcox, M.H. Clinical practice guideline by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA): 2021 focused update guidelines on management of Clostridioides difficile infection in adults. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e1029e1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auxier, B.; Anderson, M. Social Media Use in 2021. Pew Research Center. 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/ (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Guess, A.; Nagler, J.; Tucker, J. Less informed but more exposed: How young adults are vulnerable to misinformation. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau4585. [Google Scholar]

- Dube, A.; Jacobs, J.; Naidu, S.; Suri, S. Monopsony in online labor markets. American Economic Review. Insights 2020, 2, 3346. [Google Scholar]

- Cascini, F.; Pantovic, A.; Al-Ajlouni, Y.A.; Failla, G.; Puleo, V.; Melnyk, A.; Lontano, A.; Ricciardi, W. Social media and attitudes towards a COVID19 vaccination: A systematic literature review. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 48, 101454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muric, G.; Wu, Y.; Ferrara, E. COVID19 vaccine hesitancy on social media: Building a public Twitter data set of antivaccine content, vaccine misinformation, and conspiracies. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e30642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnevie, E.; Rosenberg, S.D.; Kummeth, C.; Goldbarg, J.; Wartella, E.; Smyser, J. Using social media influencers to increase knowledge and positive attitudes toward the flu vaccine. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, S.L.; Mauldin, R.F. The “anti-vax” movement: A quantitative report on vaccine beliefs and knowledge across social media. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.; Thomson, P.; Rockloff, M.J.; Pennycook, G. Going against the herd: Psychological and cultural factors underlying the ‘vaccination confidence gap’. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, N.T.; Chapman, G.B.; Rothman, A.J.; Leask, J.; Kempe, A. Increasing vaccination: Putting psychological science into action. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2017, 18, 149–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, M.M.; Holban, A.M.; Călugăreanu, A.; Orzan, O.A. Recent advances in diagnosis and therapy of skin cancers through nanotechnological approaches. In Nanostructures in Therapeutic Medicine; Grumezescu, R., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 285–306. [Google Scholar]

| Experien | Informat | SM_Messa | Financia | SM_Expos | Attitude | Decision | Social_e | Pro-Envi | D_Pro_en | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.640 | 0.813 | 0.429 | 0.731 | 0.831 | 0.770 | 0.768 | 0.788 | 0.565 | 0.753 |

| Average variances extracted | 0.415 | 0.518 | 0.417 | 0.384 | 0.505 | 0.467 | 0.524 | 0.542 | 0.475 | 0.510 |

| Q-squared | 0.617 | 0.535 | 0.318 | 0.510 | 0.521 | |||||

| R squared | 0.698 | 0.533 | 0.323 | 0.505 | 0.522 |

| Experien | Informat | SM_Messa | Financia | SM_Expos | Attitude | Decision | Social_e | Pro-Envi | D_Pro_en | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experien | (0.644) | 0.673 | 0.545 | 0.614 | 0.599 | 0.615 | 0.609 | 0.689 | 0.567 | 0.587 |

| Informat | 0.633 | (0.720) | 0.629 | 0.611 | 0.649 | 0.632 | 0.665 | 0.720 | 0.598 | 0.678 |

| SM_Messa | 0.545 | 0.699 | (0.646) | 0.612 | 0.505 | 0.456 | 0.511 | 0.623 | 0.496 | 0.591 |

| Financia | 0.664 | 0.681 | 0.612 | (0.639) | 0.601 | 0.624 | 0.653 | 0.689 | 0.622 | 0.615 |

| SM_Expos | 0.599 | 0.649 | 0.505 | 0.601 | (0.721) | 0.617 | 0.669 | 0.660 | 0.509 | 0.517 |

| Attitude | 0.615 | 0.632 | 0.456 | 0.624 | 0.717 | (0.684) | 0.650 | 0.667 | 0.548 | 0.559 |

| Decision | 0.609 | 0.665 | 0.511 | 0.623 | 0.669 | 0.650 | (0.724) | 0.669 | 0.636 | 0.560 |

| Social_e | 0.689 | 0.710 | 0.623 | 0.629 | 0.660 | 0.667 | 0.669 | (0.736) | 0.513 | 0.647 |

| Pro-Envi | 0.567 | 0.598 | 0.496 | 0.622 | 0.509 | 0.548 | 0.636 | 0.513 | (0.689) | 0.582 |

| D_Pro_en | 0.587 | 0.678 | 0.591 | 0.615 | 0.517 | 0.559 | 0.560 | 0.647 | 0.582 | (0.714) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orzan, A.-O. Social Media Influence: Bridging Pro-Vaccination and Pro-Environmental Behaviors Among Youth. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114814

Orzan A-O. Social Media Influence: Bridging Pro-Vaccination and Pro-Environmental Behaviors Among Youth. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):4814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114814

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrzan, Anca-Olguța. 2025. "Social Media Influence: Bridging Pro-Vaccination and Pro-Environmental Behaviors Among Youth" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 4814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114814

APA StyleOrzan, A.-O. (2025). Social Media Influence: Bridging Pro-Vaccination and Pro-Environmental Behaviors Among Youth. Sustainability, 17(11), 4814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114814