‘Making a Positive Environmental Impact’: Exploring the Role of Volunteering at a Campus Community Garden

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Campus Community Gardens and Student Motivations

1.2. Benefits and Challenges of Participation in a Campus Community Garden

1.3. Promoting Students’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection Procedures

2.2. Sample

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Findings

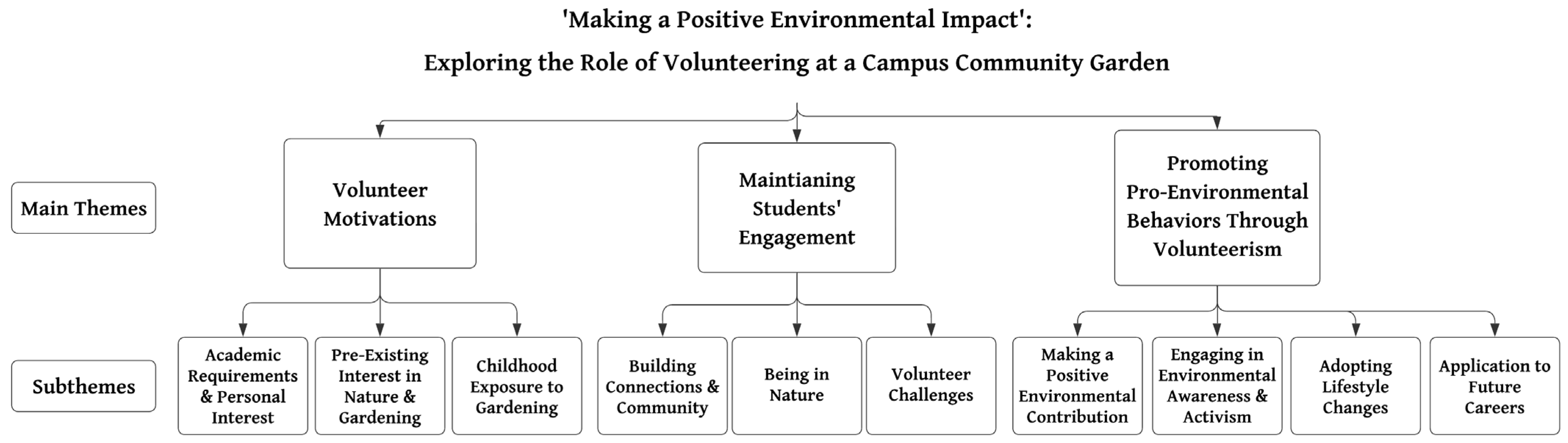

3.1. Diagram of Themes and Subthemes (See Figure 1)

3.2. Theme One: Volunteer Motivations

3.2.1. Academic Requirements and Personal Interests

3.2.2. Pre-Existing Interest in Nature and Gardening

3.2.3. Childhood Exposure to Gardening

“I think it’s a little difficult for me to sometimes communicate with my grandparents because they don’t speak a lot of English and my Mandarin is not very good, and so it’s hard to connect over something. And I think gardening was one of those things that my grandpa and I really got along with—we’re really both interested in. And I guess it just gives us opportunities to connect as well”.

3.3. Theme Two: Maintaining Students’ Engagement

3.3.1. Building Connections and Community

“My favorite part is always interacting with the other students that are volunteering…it makes more community inside the community garden [as you are] not only cultivating plants…but also cultivating relationships and networking. And I think that’s just inherently valuable”.

“I think the most important thing [I learned], honestly, was just not feeling weird to introduce myself first…sometimes it feels really awkward when you’re in a situation and no one is really speaking or introducing themselves. But in the garden, that’s something I’ve had to do multiple times. And so, it’s just something that is easier and it’s kind of nice to know that I am able to facilitate conversations now”.

“I think my favorite aspect of volunteering at the garden is getting to connect with the plants. So, the garden is trying to [have us] build relationships with our plants and our greenery, which is what our ancestors did. And so, taking the time to really sit with plants, using your five senses, smelling or touching, tasting if it’s safe to eat and using your eyes just to really observe a plant for more than its face value. And so, it’s time for you to really inspect or investigate a plant and find new things about the plants that you didn’t know before”.

3.3.2. Being in Nature

“I think a benefit would be going into a serene and relaxing environment. I feel like when I am surrounded by plants, I feel more relaxed, especially with finals and stuff. So going into a calmer environment I feel is very beneficial to my mental health. I feel like before I started work or before I started volunteering there—I was really stressed out just because of school and stuff. But then I noticed that I started to calm down more when I started volunteering there”.

3.3.3. Volunteer Challenges

“I don’t enjoy turning compost. I don’t think anyone really does. It’s crazy how hot the compost could get…there’s a lot of science in it. But yeah, it can literally start steaming. It’s really hot. It doesn’t smell great. It’s definitely not my favorite part, but I don’t mind doing it. You know, it’s also a lot of work shoveling and stuff like that, but really it’s not too bad”.

3.4. Theme Three: Promoting Pro-Environmental Behaviors Through Volunteerism

3.4.1. Making a Positive Environmental Contribution

“At the end of the day, it’s like after you finish volunteering and you see the result, you’re very motivated and you can see what you did physically, not just academically. So, you have a result. And then even when time passes, if you planted a plant, you can go back to it, even harvest it, which is the best”.

“I found it really interesting to see all of the hard work from planting seeds to watching it grow and watering it to being able to harvest fruits and vegetables. And in the end, it was really rewarding to be able to harvest as well as share the produce with the campus community at the food pantry”.

“…you get to help your community [with clean-up, reducing food waste, and being more resourceful], even if it’s in a small way… [I found] small things, even if they don’t seem like a big difference, like small things such as being more resourceful, everything matters”.

3.4.2. Engaging in Environmental Awareness and Activism

“[I learned] how composting works, when fruits and vegetables are in season, and some other stuff about plants in general. How sunflowers are spicy so that animals don’t eat them before they’re completely ripe and have germinated. I thought that was cool. So just general plant facts and how to apply the stuff you learn in the garden at home”.

“I think the most important thing I’ve learned is…that a lot of food is grown through hard work and there are a lot of people out there that have their livelihoods depending on that hard work…We spent a month trying to support fava farmers that are not very attended to—by trying to instate some form of school legislation just to support more community garden efforts…And then we were also trying to promote it on our own social media platforms to say these farmers are in need of support and they should be more valued because we get what they produce and we don’t really see how they produce it”.

3.4.3. Adopting Lifestyle Changes

“They do compost—helping reduce food waste. Obviously not everybody composts, but knowing that there are people out there that do it, it also influenced me to start bringing in my own food scraps and trying to reduce my own food waste. I feel like seeing the compost puts waste into perspective for me, knowing before I started working in the garden, my food scraps just go in the trash can and that just goes into the landfill. And now knowing it’s getting put back into earth by becoming soil, I feel like that’s a huge thing that they’re doing environmentally”.

“I feel like I go to the garden, and it helps me become a lot more conscious of environmental things…So have you ever seen that chart where it has how much water usage for different types of food? I think it was titled “How Thirsty Is Our Food”. I just briefly remember someone in the garden bringing it up, and it basically has liters of water required to produce one kilogram of the following food products. I don’t know, that was kind of an eye opener for me because Bovine meat is at the very, very top, with over 15,000 L of water required per kilogram followed by nuts and whatever else. And that kind of encouraged me to not eat as much beef or meat in general”.

“It’s definitely influenced me to want to have something like that when I have my own house or yard to be able to grow my own food that’s not from a grocery store and I can make sure it’s safe and everything. And I just think it’s pretty sustainable to have your own garden that’s clean and you don’t have to worry about extra expenses or food waste, because then you could just compost it. I think gardening is a really important thing and it’s definitely a hobby that you can have throughout your entire life”.

3.4.4. Application to Future Careers

“… [the compost] it kind of helped me realize that I’m really interested in waste diversion and wanting to reduce the amount of waste that goes into landfills on a bigger scale, on a scale of a whole city or a whole county or a whole state. And so, I think that’s kind of one of my ideal career paths would be to work with municipalities to help them figure out a system to collect food waste so that it can be composted and then that compost can be used to fertilize plants in the surrounding areas”.

4. Discussion

4.1. Motivations

4.2. Sustained Engagement

4.3. Campus Community Gardens as Sites for Promoting Pro-Environmental Behaviors

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| CCG | Campus community garden |

References

- Sustainable Campuses. College Pulse Insights. 2022. Available online: https://bit.ly/4iavM8G (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Leal Filho, W.; Aina, Y.A.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Purcell, W.; Nagy, G.J. Climate change: Why higher education matters? Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, S.; Suresh, M. Synergizing education, research, campus operations, and community engagements towards sustainability in higher education: A literature review. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 1015–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, C.; Freedman, D. Review and analysis of the benefits, purposes, and motivations associated with community gardening in the United States. J. Community Pract. 2010, 18, 458–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raneng, J.; Howes, M.; Pickering, C.M. Current and future directions in research on community gardens. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 79, 127814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Bowers, A.W.; Roth, N.W.; Holthuis, N. Environmental education and K-12 student outcomes: A review and analysis of research. J. Environ. Educ. 2018, 49, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlett, P.F. Campus sustainable food projects: Critique and engagement. Am. Anthropol. 2011, 113, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milstein, T.; Sherry, C.; Carr, J.; Siebert, M. “Got to get ourselves back to the garden”: Sustainability transformations and the power of positive environmental communication. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2024, 67, 2116–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothukuchi, K.; Molnar, S.A. Sustainable food systems at urban public universities: A survey of U-21 universities. J. Urban Aff. 2015, 37, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STARS, Sustainability Tracking Assessment & Rating System. 2025. Available online: https://stars.aashe.org/resources-support/help-center/v2-innovation-leadership/community-garden/ (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Arnett, J.J.; Jensen, L.A. Human Development: A Cultural Approach, 3rd ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gage, R.L.; Thapa, B. Volunteer motivations and constraints among college students: Analysis of the volunteer function inventory and leisure constraints models. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2012, 41, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sextus, C.P.; Hytten, K.F.; Perry, P. A systematic review of environmental volunteer motivations. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2024, 37, 1591–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Young, R.; Scheuer, K.; Roush, J.; Kozeleski, K. Student interest in campus community gardens: Sowing the seeds for direct engagement with sustainability. In The Contribution of Social Sciences to Sustainable Development at Universities; Filho, W.L., Zint, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duram, L.A.; Klein, S.K. University food gardens: A unifying place for higher education sustainability. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 9, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.J.; Morales Knight, L.F.; Wallach, J. Gardening activities, education, and self-esteem: Learning outside the classroom. Urban Educ. 2007, 42, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loso, J.; Staub, D.; Colby, S.E.; Olfert, M.D.; Kattelmann, K.; Vilaro, M.; Colee, J.; Zhou, W.; Franzen-Castle, L.; Mathews, A.E. Gardening experience is associated with increased fruit and vegetable intake among first-year college students: A cross-sectional examination. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staub, D.; Colby, S.E.; Olfert, M.D.; Kattelmann, K.; Zhou, W.; Horacek, T.M.; Greene, G.W.; Radosavljevic, I.; Franzen-Castle, L.; Mathews, A.E. A multi-year examination of gardening experience and fruit and vegetable intake during college. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Huh, M.R. Analysis of satisfaction and characteristics of using university campus gardens for enhancing the mental well-being of university students. J. People Plants Environ. 2023, 26, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, J. Campus community gardens and student health: A case study of a campus garden and student well-being. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 70, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, S.; Bacon, K.; Hee, A.; Deshpande, S. A mixed-methods explorative study on gardening and wellbeing among college students. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2023, 55, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftandilian, D.; Dart, L. Using garden-based service-learning to work toward food justice, better educate students, and strengthen campus-community ties. J. Community Engagem. Scholarsh. 2013, 6, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, R.L.; Robinson, Z. Reviewing University Community Gardens for Sustainability: Taking stock, comparisons with urban community gardens and mapping research opportunities. Local Environ. 2018, 23, 652–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-Rueda, N.; Guillén-Royo, M.; Guardiola, J. Pro-environmental behavior, connectedness to nature, and wellbeing dimensions among Granada students. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Null, D.C.; Asirvatham, J. College students are pro-environment but lack sustainability knowledge: A study at a mid-size Midwestern US university. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2023, 24, 660–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, A.M.; Knoch, D.; Berger, S. When and how pro-environmental attitudes turn into behavior: The role of costs, benefits, and self-control. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 79, 101748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohmah, I.N.; Salsabila, Z.; Andriyani, A.; Wati, I.R. Analysis of pro-environmental behavior in college students: A literature review. Res. Horiz. 2024, 4, 409–420. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Basics of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 860–886. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asah, S.T.; Bengston, D.N.; Westphal, L.M. The influence of childhood: Operational pathways to adulthood participation in nature-based activities. Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 545–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izenstark, D.; Middaugh, E. Patterns of family-based nature activities across the early life course and their association with adulthood outdoor participation and preference. J. Leis. Res. 2022, 53, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuß, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Marquez, S.; Cirach, M.; Dadvand, P.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Gidlow, C.; Grazuleviciene, R.; Kruize, H.; Zijlema, W. Low childhood nature exposure is associated with worse mental health in adulthood. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, N.M.; Lekies, K.S. Nature and the life course: Pathways from childhood nature experiences to adult environmentalism. Child. Youth Environ. 2006, 16, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, T.; Tracey, D.; Truong, S.; Ward, K. Community gardens as local learning environments in social housing contexts: Participant perceptions of enhanced wellbeing and community connection. Local Environ. 2022, 27, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, W.I.; Dillon, D. Community gardening: Stress, well-being, and resilience potentials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soga, M.; Cox, D.; Yamaura, Y.; Gaston, K.; Kurisu, K.; Hanaki, K. Health benefits of urban allotment gardening: Improved physical and psychological well-being and social integration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izenstark, D.; Ebata, A.T. Theorizing family-based nature activities and family functioning: The integration of Attention Restoration theory with a family routines and rituals perspective. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2016, 8, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izenstark, D.; Ebata, A.T. The effects of the natural environment on attention and family cohesion: An experimental study. Child. Youth Environ. 2017, 27, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.T.C.; Shanahan, D.F.; Hudson, H.L.; Plummer, K.E.; Siriwardena, G.M.; Fuller, R.A.; Anderson, K.; Hancock, S.; Gaston, K.J. Doses of neighborhood nature: The benefits for mental health of living with nature. BioScience 2017, 67, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackey, N.Q.; Tysor, D.A.; McNay, G.D.; Joyner, L.; Baker, K.H.; Hodge, C. Mental health benefits of nature-based recreation: A systematic review. Ann. Leis. Res. 2021, 24, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Development. World Bank. 2025. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/overview (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Diekmann, A.; Preisendörfer, P. Green and greenback: The behavioral effects of environmental attitudes in low-cost and high-cost situations. Ration. Soc. 2003, 15, 441–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izenstark, D.; Boone, B. Exploration of emerging adults’ volunteer experiences at a campus community garden. Presented at the Society for Research on Adolescence Biennial Meeting, Chicago, IL, USA, 18–20 April 2024.

| Category | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 20 | 80% |

| Male | 3 | 12% |

| Non-Binary | 2 | 8% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Asian American | 13 | 52% |

| White | 6 | 24% |

| Latinx/Hispanic | 4 | 16% |

| Mixed-race | 2 | 8% |

| Year in School | ||

| Fourth Year+ | 18 | 72% |

| Third Year | 3 | 12% |

| Second Year | 4 | 16% |

| First Year | 0 | 0% |

| On/Off Campus | ||

| On Campus | 5 | 20% |

| Off Campus | 20 | 80% |

| Hours Volunteered | ||

| 9+ | 10 | 40% |

| 6–9 | 5 | 20% |

| 3–6 | 4 | 16% |

| <3 | 6 | 24% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Izenstark, D.; Boone, B.A. ‘Making a Positive Environmental Impact’: Exploring the Role of Volunteering at a Campus Community Garden. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4951. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114951

Izenstark D, Boone BA. ‘Making a Positive Environmental Impact’: Exploring the Role of Volunteering at a Campus Community Garden. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):4951. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114951

Chicago/Turabian StyleIzenstark, Dina, and Barbara Ann Boone. 2025. "‘Making a Positive Environmental Impact’: Exploring the Role of Volunteering at a Campus Community Garden" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 4951. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114951

APA StyleIzenstark, D., & Boone, B. A. (2025). ‘Making a Positive Environmental Impact’: Exploring the Role of Volunteering at a Campus Community Garden. Sustainability, 17(11), 4951. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114951