Challenges That Need to Be Addressed before Starting New Emergency Remote Teaching at HEIs and Proposed Solutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

- ERT is implemented as a fully remote teaching solution for education, delivered for the duration of a crisis and consisting of online, blended or hybrid courses.

- ERT tends to provide temporary access to education in a manner that is quick to set up and is readily available during an emergency or crisis.

- Once the crisis subsides, ERT switches to the previous way of teaching or evolves into a more resilient and improved version.

- During crises, preparation time is limited, leading to ERT being implemented with minimal or no prior preparation in the organizational, pedagogical and technical aspects.

2. Literature Review

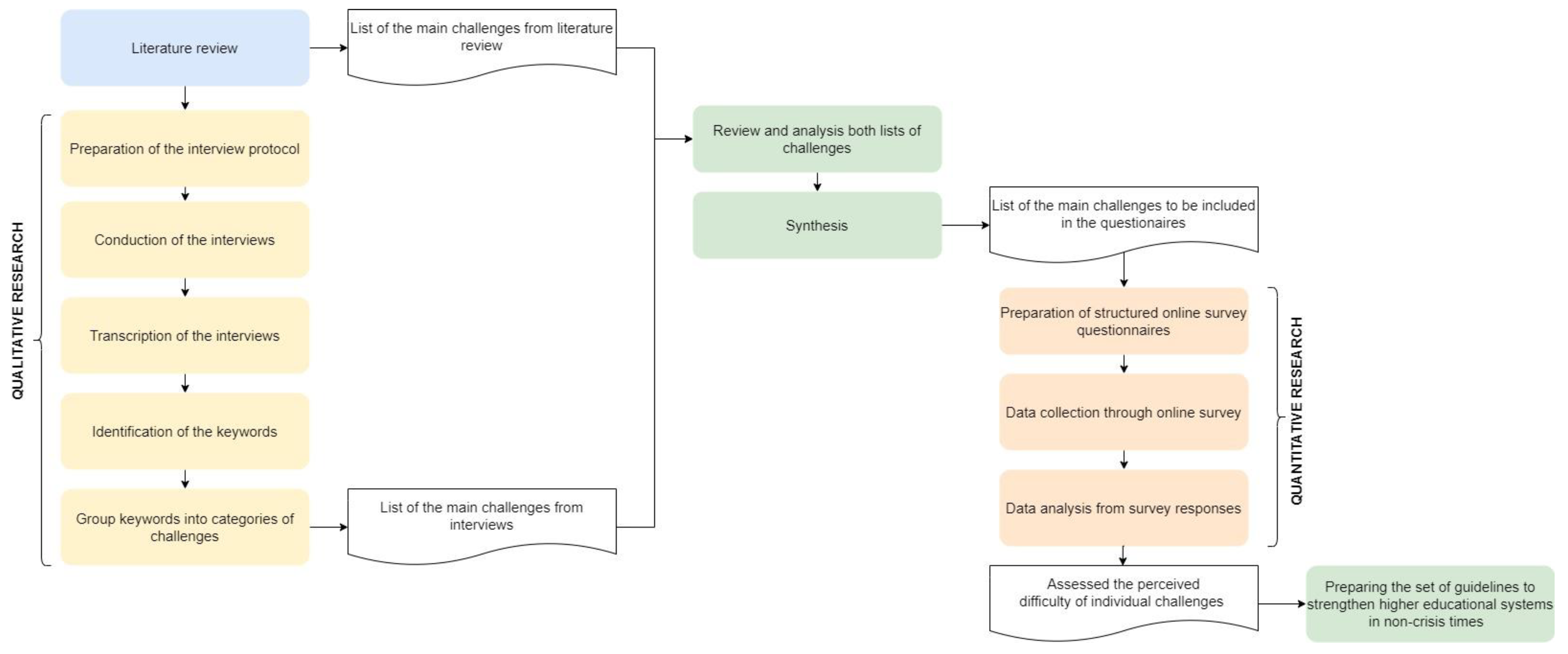

3. Methods

- RQ1: What challenges did students participating in ERT face in the period from March 2020 to March 2021?

- RQ2: What challenges did professors face during the implementation of ERT in the period from March 2020 to March 2021?

4. Results

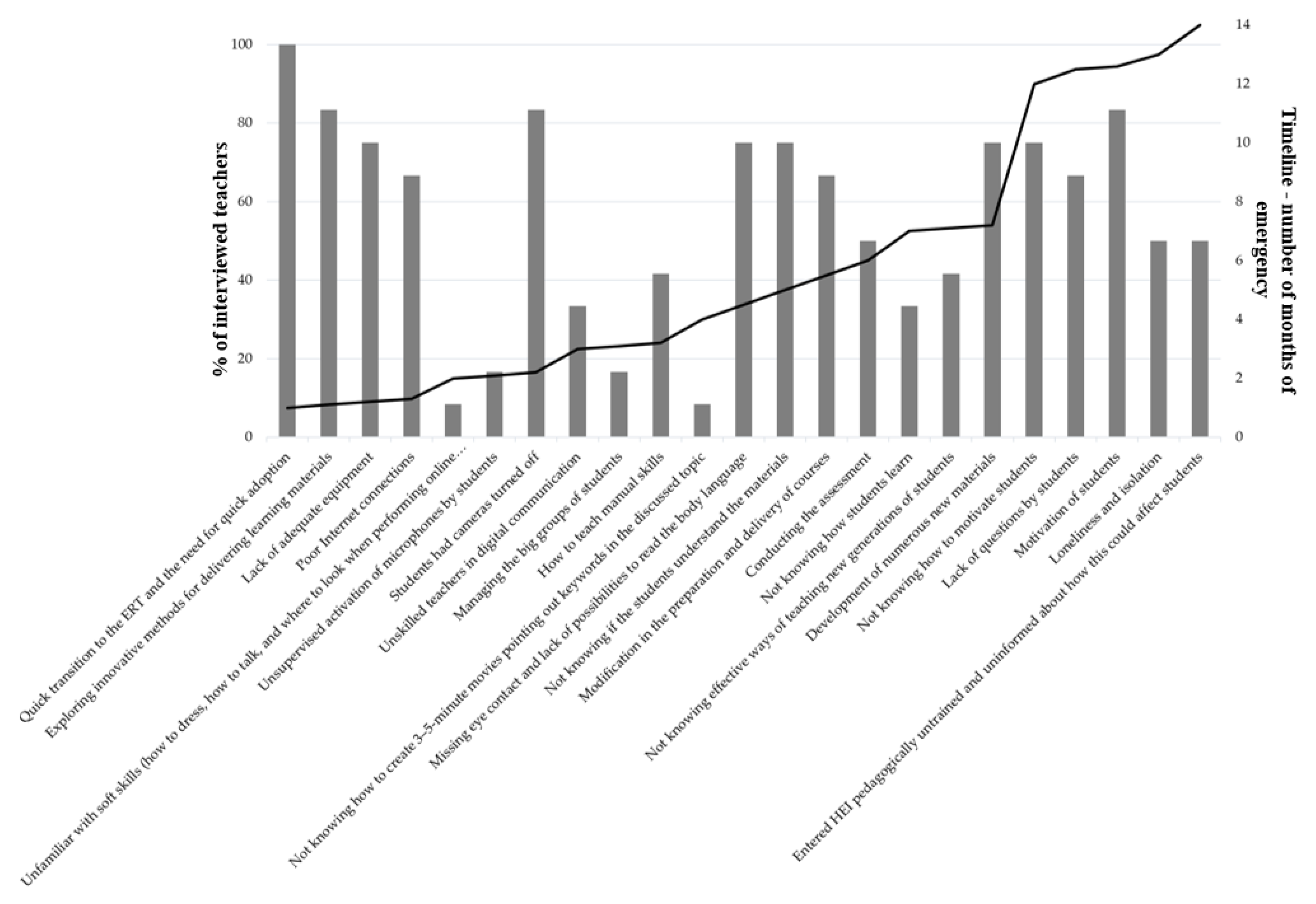

4.1. Qualitative Research—Interviews: Reported Teachers’ and Students’ Challenges at Practicing Emergency Remote Teaching

4.2. Quantitative Research—Survey: A Detailed Insight into the Perceived Difficulty of Challenges in Implementing Emergency Remote Teaching

4.2.1. An Insight into the Perceived Difficulty of Challenges from the Teachers’ Perspective

- Quick changes from live classes to online classes (p = 0.007);

- Learning new teaching methods (p < 0.001);

- Developing new resources and implementing them effectively (p = 0.009);

- Not appropriately preparing lectures (p = 0.045);

- Slow/less response of students (p = 0.001).

4.2.2. An Insight into the Perceived Difficulty of Challenges from the Students’ Perspective

5. Discussion

- Intensive establishment of gigabit infrastructure and equipping households—as well as educational institutions—with essential information and communication equipment for virtual communication. According to interviews with professors and students, when ERT started, technical challenges, such as internet access, were the most present and, to a lesser extent, represented an insurmountable obstacle. Many students did not own cameras. However, when the cameras were bought, it turned out that many switched-on cameras slowed down or even interrupted the online event. The switched-on cameras have often disturbed the participants’ focus, as they had an insight into the intimacy of the home environment of others. It slowly became a given that the cameras remained off. Teachers who used ICT for all teaching hours for the first time during the imposed transition to ERT turned out to be poorly prepared and unprofessional in the eyes of the students. The resulting slow processing of teaching material often bored students and allowed them to shift their attention to other stimuli from their home environment.

- Familiarize students and teachers with the nature of virtual environments. During the initial implementation of ERT, teachers had to learn how to teach in front of cameras, setting a neutral background, dressing, etc. Students did not receive these skills. Even though the teachers improved their approach to teaching in front of cameras, it did not stop the students from retreating behind the cameras. It was detected that there was also a discernible reduction in the level of interaction between teachers and students. The teachers rated the difficulty of this challenge highly, as they did not know how their specific teaching method in front of the cameras affected the students’ engagement. Some of the interviewed teachers have stopped improving themselves pedagogically precisely because of the lack of feedback. Teachers’ and students’ digital competencies need to be developed synchronously since ERT requires competence on both sides. Including some virtual sessions in the regular lectures could contribute to addressing this situation. Indeed, it can be argued that HEIs that permanently teach online are more resilient to crises than those that traditionally teach students in physical classrooms. With them, technical challenges in the transition to ERT are hardly to be expected. Also, a minimal occurrence of methodological and pedagogical challenges could be expected due to a busy schedule with interventions of support services within HEIs.

- Continuous upgrading of digital competencies and training materials. Interviews with professors revealed a challenge of low teachers’ digital, methodological, social, and pedagogical competencies during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was solved by the individual’s self-education or education initiated by the HEIs. This complicated the task of adapting the existing training materials to new learning environments. It could be argued that post-lockdown teachers are better qualified to implement online teaching than pre-ERT on average. In the interviews with the professors, we also noticed that only 10% of them upgraded their competences beyond the necessary scope. We could conclude that after the end of ERT, most professors stop upgrading their competences (and training materials) if there is no external motivator. The present study concludes that the core challenge is not a lack of students’ motivation or engagement but rather a mechanism that would motivate teachers and students to improve.

- Foster the usage of multiple communication channels between participants in the pedagogical process. After a year and a half of the imposed transition to ERT, the social challenges completely overshadowed the technical ones. Social challenges, also researched by [6,16,17,24,25,26], were observed to the greatest extent in online teaching and less in hybrid and distant modes. Despite meeting in real-time in the online classroom, there was a lack of communication, which could have smoothed the stress of teachers and students. Students inherently predisposed towards shyness and reservedness faced limited opportunities to transcend their natural limitations, as the teachers could not detect their condition due to the cameras being switched off. The lack of communication made it difficult for all students to participate, which is one of the characteristics of sustainable learning. Sustainable learning is defined as long-lasting, continuous, participative, purposeful, renewable, and habitual [38,48].

- Co-creation of educational systems with HEIs, teachers, and students. Past experiences with ERT have revealed that teachers face the challenges of ERT organized within the auspices of the departments, while the students are not organized to function as a unit in times of crises. The teachers were able to foresee the challenges because, despite the lockdown, there was minimal time for planning. HEIs, on the other hand, put students in front of the facts with almost no choices. Involving students in the planning phase of ERT would help reduce stress on the part of students and allow them to prepare themselves and solve potential problems earlier. Teachers would be aware of students’ challenges, and students would be aware of teachers’ challenges. They would mutually develop a platform of trust and a sense of safety, which is the basis for information exchange and interaction. The lack of interaction was mainly reflected in the students’ lack of motivation, shortened students’ attention span, and unresponsiveness. Investing efforts in organizing students into operational units during non-crisis times can pay off during ERT in the form of greater student engagement and, consequently, better learning outcomes.

- Stimulate students’ motivation and engagement by exploring different teaching methods and tools. Researching live examples of ERT revealed that low student motivation stood out in the field of social challenges. It is believed that if teachers can help students develop a strong motivation to learn, this can significantly improve students’ learning outcomes [49]. Experiments in educational psychology show that students’ motivation drives learning activities, stimulates students’ interest in learning, maintains a certain level of arousal, and leads to certain learning activities [50]. Teachers should constantly try new teaching methods and plan interesting activities to stimulate students’ interest in learning and thus enhance their subjective initiative [49]. To motivate students, it is necessary to know what motivates them, but contrary to expectations, interviewed teachers in the present research reported a lack of knowledge on how their activities in front of cameras encourage students. The current study also confirms a lower level of pedagogical competences of teachers as already discussed by other authors [6,21,23,24,27,30]. During ERT implementation, teachers recognized the need to adapt teaching methods to the ERT teaching environment. However, they were less aware of where to get acquainted with appropriate teaching methods and how different teaching methods could be effectively used within ERT. As a result, teachers mostly refrained from choosing the most suitable teaching methods, clinging to previous knowledge as they tried to cope with the preparation of teaching materials, monitoring the student performance, and finding ways of formative assessment that were compatible with ERT. The teachers interviewed admitted that they knew that many online applications and software tools were available to help them with ERT, but they lacked time and energy to find them and learn how to use them. The challenge of learning how to use different online teaching aids was already discussed in the scientific literature before the imposed transition to ERT [51,52]. The lockdown only made the challenge relevant in practice. The present study supports the need for the creation of databases of teaching methods and digital teaching aids, as well as the result of illustrative short instructions that help future users to master the necessary basics in a very short time.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crawford, J.; Butler-Henderson, K.; Rudolph, J.; Malkawi, B.; Glowatz, M.; Burton, R.; Magni, P.A.; Lam, S. COVID-19: 20 countries’ higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2020, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, S.J. Education and the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospects 2020, 49, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, D.T.; Shannon, D.M.; Love, S.M. How teachers experienced the COVID-19 transition to remote instruction. Phi Delta Kappan 2020, 102, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trust, T.; Whalen, J. Should teachers be trained in emergency remote teaching? Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2020, 28, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Pillay, A. South African Postgraduate STEM Students’ Use of Mobile Digital Technologies to Facilitate Participation and Digital Equity during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, F.; Grifoni, P.; Guzzo, T. Online Learning and Emergency Remote Teaching: Opportunities and Challenges in Emergency Situations. Societies 2020, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, C.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.; Trust, T.; Bond, A. The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Educ. Rev. 2020, 27, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Khlaif, Z.N.; Salha, S.; Kouraichi, B. Emergency remote learning during COVID-19 crisis: Students’ engagement. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 7033–7055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achen, K.; Rutledge, D. The Transition from Emergency Remote Teaching to Quality Online Course Design: Instructor Perspectives of Surprise, Awakening, Closing Loops, and Changing Engagement. Community Coll. J. Res. Pract. 2023, 47, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barquero, V.V.; Arce, N.G.; León, S.M. Transitioning from face-to-face classes to emergency remote learning. Rev. Leng. Mod. 2022, 10, 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.; Chung, S.Y.; Ko, J. Rethinking teacher education policy in ICT: Lessons from emergency remote teaching (ERT) during the COVID-19 pandemic period in Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A.; Sharma, R.C. Emergency remote teaching in a time of global crisis due to CoronaVirus pandemic. Asian J. Distance Educ. 2020, 15, i–vi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Pradas, S.; Hernández-García, Á.; Chaparro-Peláez, J.; Prieto, J.L. Emergency remote teaching and students’ academic performance in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, 106713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlejohn, A.; Gourlay, L.; Kennedy, E.; Logan, K.; Neumann, T.; Oliver, M.; Potter, J.; Rode, J.A. Moving Teaching Online: Cultural Barriers Experienced by University Teachers during COVID-19. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2021, 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, S.; Jung, H. Exploring University Instructors’ Challenges in Online Teaching and Design Opportunities during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2021, 20, 308–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arja, S.B.; Fatteh, S.; Nandennagari, S.; Pemma, S.S.K.; Ponnusamy, K.; Arja, S.B. Is Emergency Remote (Online) Teaching in the First Two Years of Medical School During the COVID-19 Pandemic Serving the Purpose? Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2022, 13, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramarenco, R.E.; Burcă-Voicu, M.I.; Dabija, D.-C. Student Perceptions of Online Education and Digital Technologies during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Electronics 2023, 12, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drane, C.; Vernon, L.; O’Shea, S. The Impact of ‘Learning at Home’ on the Educational Outcomes of Vulnerable Children in Australia during the COVID-19 Pandemic; Literature Review prepared by the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education; Curtin University: Bentley, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Wan, B. The digital divide in online learning in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Technol. Soc. 2022, 71, 102122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owusu-Fordjour, C.; Koomson, C.K.; Hanson, D. The impact of COVID-19 on learning—The perspective of the ghanaian student. Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 2020, 7, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, J.E.; Pohan, C. Resilient Instructional Strategies: Helping Students Cope and Thrive in Crisis. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 2021, 22, ev22i1.2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ülger, K. Uzaktan Eğitim Modelinde Karşılaşılan Sorunlar-Fırsatlar ve Çözüm Önerileri. Intern. J. Contemp. Educ. Stud. 2021, 7, 393–412. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachopoulos, D. COVID-19: Threat or Opportunity for Online Education? High. Learn. Res. Commun. 2011, 10, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizka, L.; Probst, G. Learning during (or despite) COVID-19: Business students’ perceptions of online learning. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2023, 31, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir-Inbal, T.; Blau, I. Facilitating Emergency Remote K-12 Teaching in Computing-Enhanced Virtual Learning Environments during COVID-19 Pandemic—Blessing or Curse? J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2021, 59, 1243–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, M.M.M.A.; Alhamad, M.M. Emergency remote teaching of foreign languages at Saudi universities: Teachers’ reported challenges, coping strategies and training needs. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 8919–8944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, B.N.Y.; Ahmad, J. Are we Prepared Enough? A Case Study of Challenges in Online Learning in A Private Higher Learning Institution during the COVID-19 Outbreaks. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2020, 7, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusmann, B.; Trippenzee, M.; Fokkens-Bruinsma, M.; Sanderman, R.; Schroevers, M.J. Providing emergency remote teaching: What are teachers’ needs and what could have helped them to deal with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic? Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 118, 103815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimers, F.; Schleicher, A.; Saavedra, J.; Tuominen, S. Supporting the Continuation of Teaching and Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Annotated Resources for Online Learning. Available online: https://globaled.gse.harvard.edu/files/geii/files/supporting_the_continuation_of_teaching.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2023).

- Bacon, K.L.; Peacock, J. Sudden challenges in teaching ecology and aligned disciplines during a global pandemic: Reflections on the rapid move online and perspectives on moving forward. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 3551–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, K.; Javed, K.; Arooj, M.; Sethi, A. Advantages, Limitations and Recommendations for online learning during COVID-19 pandemic era: Online learning during COVID-19 pandemic era. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, S27–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, D.C.; Grajek, S. Faculty Readiness to Begin Fully Remote Teaching. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/blogs/2020/3/faculty-readiness-to-begin-fully-remote-teaching (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Johnson, N.; Veletsianos, G.; Seaman, J. U.S. Faculty and Administrators’ Experiences and Approaches in the Early Weeks of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Online Learn. 2020, 24, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, P.D.; Gregersen, T.; Mercer, S. Language teachers’ coping strategies during the COVID-19 conversion to online teaching: Correlations with stress, wellbeing and negative emotions. System 2020, 94, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bol, T. Inequality in homeschooling during the Corona crisis in the Netherlands. First results from the LISS Panel. SocArXiv 2020. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, D.O. COVID-19: Exacerbating Educational Inequalities? Public Policy.IE. Available online: https://publicpolicy.ie/covid/covid-19-exacerbating-educational-inequalities/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Thomas, M.S.C.; Rogers, C. Education, the science of learning, and the COVID-19 crisis. Prospects 2020, 49, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilkington, L.I.; Hanif, M. An account of strategies and innovations for teaching chemistry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2021, 49, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, F.; Budhrani, K.; Wang, C. Examining Faculty Perception of Their Readiness to Teach Online. Online Learn. 2019, 23, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, J. Teaching Online—A Time Comparison. Online J. Distance Learn. Adm. 2005, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X. Challenges of ‘School’s Out, But Class’s on’ to School Education: Practical Exploration of Chinese Schools during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sci. Insights Educ. Front. 2020, 5, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looi, K.H. Dataset of Challenges of Emergency Remote Teaching in Malaysia; Xiamen University: Xiamen, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golicic, S.L.; Davis, D.F.; McCarthy, M.T. A Balanced Approach to Research in Supply Chain Management. In Research Methodologies in Supply Chain Management; Kotzab, V.H., Seuring, R., Müller, M., Reiner, G., Eds.; Physica-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gosling, D.; Moon, J. How to Use Learning Outcomes and Assessment Criteria, 3rd ed.; SEEC: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gauda, K. Influence of an educational film on the effectiveness of technical education. Adv. Sci. Technol.-Res. J. 2013, 7, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, P.G.; Moreto, G.; Blasco, M.G.; Levites, M.R.; Janaudis, M.A. Education through Movies: Improving teaching skills and fostering reflection among students and teachers. J. Learn. Arts Res. J. Arts Integr. Sch. Communities 2015, 11, n1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schlesselman, L.S. Perspective from a Teaching and Learning Center during Emergency Remote Teaching. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, ajpe8142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sälzer, C.; Roczen, N. Assessing global competence in PISA 2018: Challenges and approaches to capturing a complex construct. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Glob. Learn. 2018, 10, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wang, Q.; Chin, N.S.; Teo, E.W. Analysis of Learning Motivation and Burnout of Malaysian and Chinese College Students Majoring in Sports in an Educational Psychology Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 691324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Koka, A.; Hein, V.; Tilga, H.; Raudsepp, L. Motivational processes in physical education and objectively measured physical activity among adolescents. J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, H.-H.; Weng, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-H. Which students benefit most from a flipped classroom approach to language learning? Flipped classroom does not fit all students. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 49, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, R.A.; Kamsin, A.; Abdullah, N.A. Challenges in the online component of blended learning: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2020, 144, 103701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé-Beteta, X.; Navarro, J.; Gajšek, B.; Guadagni, A.; Zaballos, A. A Data-Driven Approach to Quantify and Measure Students’ Engagement in Synchronous Virtual Learning Environments. Sensors 2022, 22, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Challenge | Challenge | References |

|---|---|---|

| Technical | No or low-performance internet connection | Drane et al. (2020); Ferri et al. (2020); Owusu-Fordjour (2020); Guo & Wan (2022); Shay & Pohan (2021); Ülger (2018), Vlachopoulos (2020); Trust & Whalen (2020); Arja et al. (2022); Zizka & Probst (2022); Cramarenco et al. (2023) [4,6,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] |

| Lack of electronic devices/ICT equipment | Ferri et al. (2020); Guo & Wan (2022); Shay & Pohan (2021); Shamir-Inbal & Blau (2021); Cramarenco et al. (2023) [6,17,19,21,25] | |

| Inability to access online tools and SW by students | Latif & Alhamad (2023) [26] | |

| Lack of technological knowledge | Yusuf (2020); Shamir-Inbaul & Blau (2021) [25,27] | |

| Lack of digital skills | Ferri et al. (2020); Trust & Whalen (2020); Klusmann et al. (2022); Reimers et al. (2020); Cramarenco et al. (2023) [4,6,17,28,29] | |

| Pedagogical | Traditional learning methods do not meet the needs of ERT | Ferri et al. (2020); Bacon & Peacock (2021); Shamir-Inbal & Blau (2021); Mukhtar (2020) [6,25,30,31] |

| Need to change navigation through the course | Brooks & Grajek (2020), Johnson et al. (2020); Mukhtar (2020); Cramarenco et al. (2023) [17,31,32,33] | |

| Lack of structured content versus the abundance of online resources | Ferri et al. (2020), Maclntyre et al. (2020) [6,34] | |

| Finding new ways of formative assessment | Brooks & Grajek (2020); Johnson et al. (2020); Shamir-Inbal & Blau (2021) [25,32,33] | |

| Students do not use cameras | Arja et al. (2022) [16] | |

| Social | Lack of interactivity and motivation of students | Bol (2020); Doyle (2020); Ferri et al. (2020); Latif & Alhamad (2023); Thomas & Rogers (2020); Shamir-Inbal & Blau (2021); Arja et al. (2022); Zizka & Probst (2022); Cramarenco et al. (2023) [6,16,17,24,25,26,35,36,37] |

| Loss of human interaction between teachers and students and among students themselves | Ferri et al. (2020); Arja et al. (2022); Zizka & Probst (2022) [6,13,24] | |

| Non-responsive students | Latif & Alhamad (2023) [26] | |

| Feeling overwhelmed with all the online learning resources and tools available | Trust & Whalen (2020) [4] | |

| Loneliness and anxiety | Shamir-Inbal & Blau (2021) [25] |

| Methodological Tool Used | |

|---|---|

| Literature review | |

| Interviews |

|

| Structured online survey |

|

| Challenge | Teachers (%) | Students (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Modification in the preparation and delivery of courses | 66.67 | / |

| Quick transition to the ERT and the need for quick adoption | 100 | 75 |

| Development of numerous new materials | 75 | / |

| Exploring innovative methods for delivering learning materials | 83.33 | / |

| Motivation of students | 83.33 | / |

| Lack of adequate equipment | 75 | 87.5 |

| How to teach manual skills | 41.67 | / |

| Managing big groups of students | 16.67 | / |

| Students had cameras turned off | 83.33 | / |

| Unsupervised activation of microphones by students | 16.67 | 18.75 |

| Poor internet connections | 66.67 | 43.75 |

| Lack of eye contact and no options to read the body language | 75 | 56.25 |

| Loneliness and isolation | 50 | 68.75 |

| Not knowing if the students understand the class content | 75 | / |

| Lack of questions by students | 66.67 | 31.25 |

| Conducting the assessment | 50 | / |

| Not knowing effective ways of teaching new generations of students | 41.67 | / |

| Not knowing how students learn | 33.33 | / |

| Not knowing how to motivate students | 75 | / |

| Not knowing how to create 3–5 min movies pointing out keywords in the discussed topic | 8.33 | / |

| Entered HEI pedagogically untrained and uninformed about how this could affect students | 50 | / |

| Teachers unskilled in digital communication | 33.33 | 43.75 |

| Unfamiliar with soft skills (how to dress, how to talk, and where to look when performing online activities) | 8.33 | / |

| Students understood less of the content delivered | / | 50 |

| Challenge | Type of Challenge *** | Perceived Level of Difficulty Regarding the Teaching Mode | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online | Hybrid | ||||

| Average * | Std | Average | Std ** | ||

| No personal contact with students | S | 3.9 | 1.20 | 3.7 | 1.26 |

| Not knowing if students understand the lecturers and are engaged with the session | S | 3.7 | 1.26 | 3.5 | 1.25 |

| Slow/less response from students | S | 3.4 | 1.29 | 3.2 | 1.18 |

| Not knowing how to provide the students with hands-on experience in the laboratory | M | 3.3 | 1.47 | 3 | 1.32 |

| Low level of students’ motivation | S | 3.3 | 1.21 | 2.9 | 1.21 |

| Difficult cooperation between students because they do not know/see each other | S | / | / | 3.1 | 1.16 |

| Developing new resources and implementing them effectively | M | 3 | 1.24 | 2.9 | 1.20 |

| Speed of the shift from face-to-face lectures to ERT | M | 2.8 | 1.42 | 2.7 | 1.21 |

| Learning new teaching methods | P | 2.7 | 1.18 | 2.6 | 1.19 |

| Not appropriately prepared for online events | M | 2.6 | 1.28 | 2.4 | 1.10 |

| Technical problems with internet connection | T | 2.5 | 1.26 | 2.4 | 1.34 |

| Technical problems with software use | T | 2.3 | 1.15 | 2.3 | 1.35 |

| Technical problems with cameras and microphones | T | 2.2 | 1.03 | 2.3 | 1.31 |

| Low digital competence of students | T | 2.2 | 1.08 | 2 | 1.15 |

| Average Time to Prepare One Pedagogical Hour | Teaching Mode | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Face-to-Face | Online | Hybrid | ||||

| No. of Teachers | % | No. of Teachers | % | No. of Teachers | % | |

| Less than 1 h | 47 | 20.26 | 12 | 5.17 | 9 | 3.88 |

| 1 h to 2 h | 85 | 36.64 | 75 | 32.33 | 58 | 25 |

| 2 h to 4 h | 68 | 29.31 | 89 | 38.36 | 65 | 28 |

| More than 4h | 24 | 10.35 | 54 | 23.28 | 32 | 13.79 |

| No experience | 8 | 3.45 | 4 | 1.72 | 68 | 29.31 |

| Sum | 232 teachers (100%) | |||||

| Statement | Teaching Mode | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online | Hybrid | |||

| No. of Teachers | % | No. of Teachers | % | |

| Less teaching material than for face-to-face | 53 | 29.44 | 18 | 19.78 |

| The exact amount of teaching material for face-to-face | 102 | 56.67 | 70 | 76.92 |

| More teaching material than for face-to-face | 25 | 13.89 | 3 | 3.30 |

| Challenge | Perceived Level of Difficulty Regarding to the Teaching Mode | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online | Hybrid | |||

| Average * | Std ** | Average | Std | |

| No spontaneous student–student contact | 3.6 | 1.3 | - | - |

| Low self-discipline | 3.3 | 1.47 | 3.1 | 1.33 |

| Not willing to speak out/ask questions in public | 3.2 | 1.36 | - | - |

| No personal contact with teachers | 3.1 | 1.38 | - | - |

| Low level of digital competence among teachers | 3.1 | 1.39 | - | - |

| Low level of self-motivation | 3.1 | 1.43 | - | - |

| Often only voice communication | 3.1 | 1.39 | - | - |

| Technical problems with the internet connection | 3.0 | 1.44 | 3 | 1.35 |

| Rare opportunities to interact, discuss and ask questions | 3.0 | 1.41 | - | - |

| The teacher’s inability to maintain contact with all students | 3 | 1.34 | 3 | 1.36 |

| Poorly prepared lectures/tutorials | 2.9 | 1.36 | - | - |

| The rapid change from physical face-to-face teaching to online | 2.8 | 1.5 | - | - |

| In the lectures, I understood less than I did before ERT | 2.8 | 1.36 | - | - |

| Not knowing how to use software | 2.6 | 1.39 | 2.6 | 1.33 |

| Technical problems with cameras and microphones | 2.6 | 1.39 | 2.7 | 1.39 |

| Motivational Factors | Average Motivational Impact | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Teacher’s teaching methods | 4.4 | 0.84 |

| Student’s interest in the course content | 4.4 | 0.75 |

| The strength of desire to complete studies | 4.1 | 0.99 |

| Teacher’s personality | 4 | 0.95 |

| Access to materials | 3.8 | 1.05 |

| Mode of study (online, live, etc.) | 3.6 | 1.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Šinko, S.; Navarro, J.; Solé-Beteta, X.; Zaballos, A.; Gajšek, B. Challenges That Need to Be Addressed before Starting New Emergency Remote Teaching at HEIs and Proposed Solutions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031144

Šinko S, Navarro J, Solé-Beteta X, Zaballos A, Gajšek B. Challenges That Need to Be Addressed before Starting New Emergency Remote Teaching at HEIs and Proposed Solutions. Sustainability. 2024; 16(3):1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031144

Chicago/Turabian StyleŠinko, Simona, Joan Navarro, Xavier Solé-Beteta, Agustín Zaballos, and Brigita Gajšek. 2024. "Challenges That Need to Be Addressed before Starting New Emergency Remote Teaching at HEIs and Proposed Solutions" Sustainability 16, no. 3: 1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031144

APA StyleŠinko, S., Navarro, J., Solé-Beteta, X., Zaballos, A., & Gajšek, B. (2024). Challenges That Need to Be Addressed before Starting New Emergency Remote Teaching at HEIs and Proposed Solutions. Sustainability, 16(3), 1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031144