From Global Goals to Classroom Realities: The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Promoting Teacher Wellbeing in Higher Education

Abstract

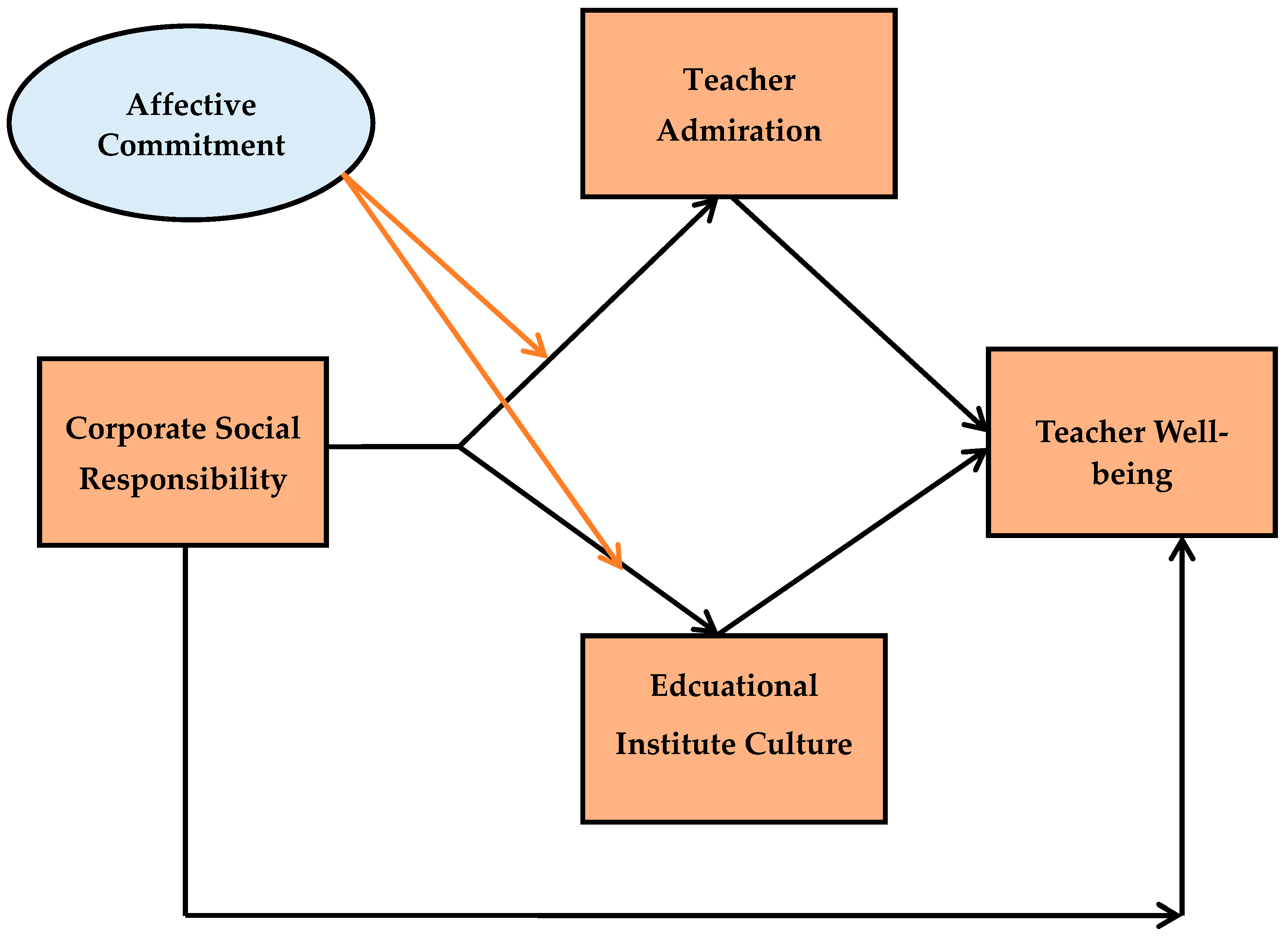

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

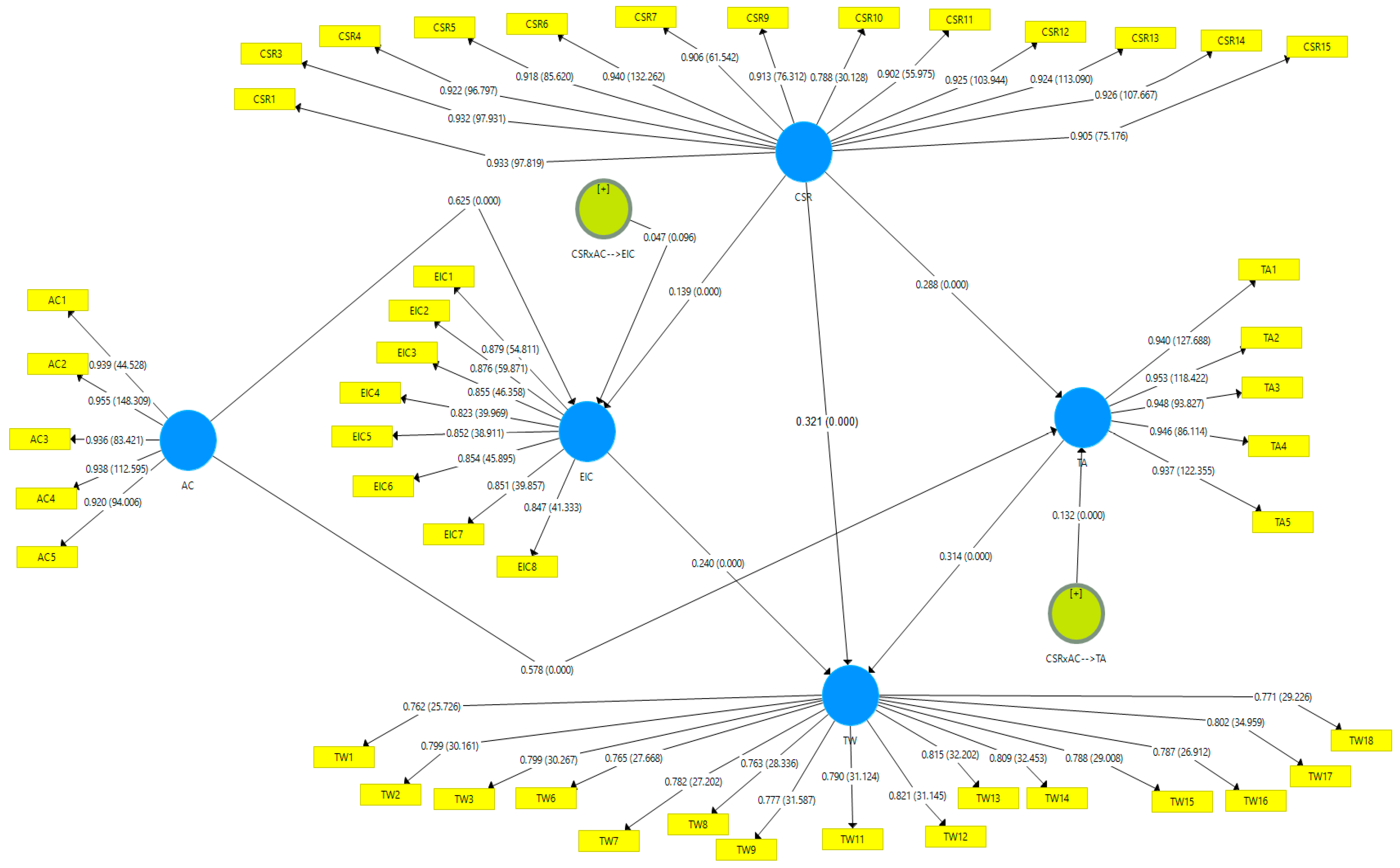

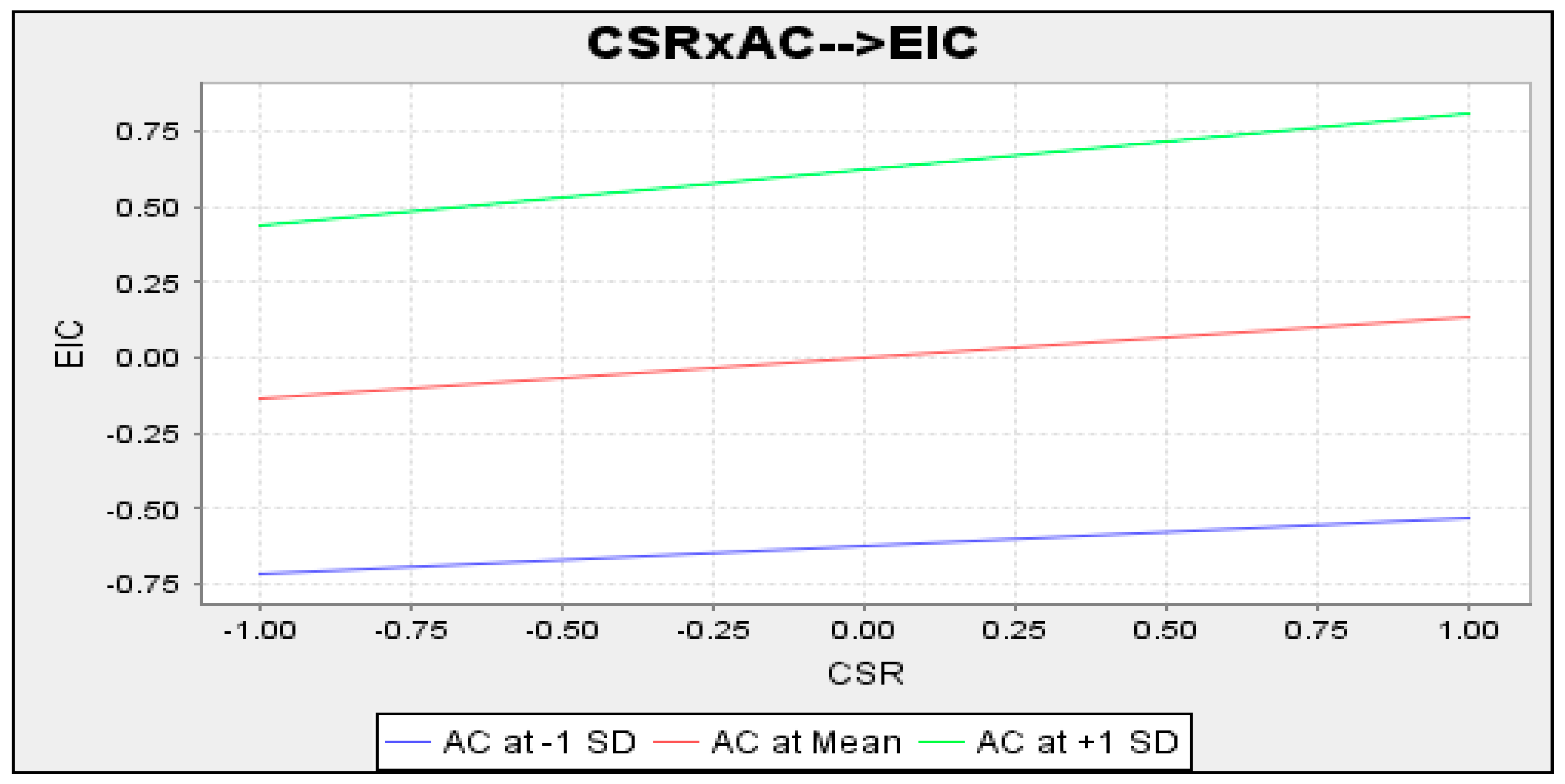

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Item | Scale | Item Description |

|---|---|---|

| CSR1 | CSR | Environmental issues are an integral part of my educational institute’s strategy. |

| CSR2 | CSR | My educational institute participates in activities that aim to protect and improve the quality of the natural environment. |

| CSR3 | CSR | My educational institute implements special programs to minimize its negative impact on the natural environment. |

| CSR4 | CSR | My educational institute takes great care so that our work does not harm the environment. |

| CSR5 | CSR | My educational institute develops activities to reduce the consumption of energy and other resources. |

| CSR6 | CSR | My educational institute targets sustainable growth that considers future generations. |

| CSR7 | CSR | My educational institute makes investments to create a better life for future generations. |

| CSR8 | CSR | My educational institute supports non-governmental organizations working in problematic areas. |

| CSR9 | CSR | My educational institute contributes to campaigns and projects that promote the well-being of society. |

| CSR10 | CSR | My educational institute contributes to cultural and charitable projects aimed at promoting the well-being of society. |

| CSR11 | CSR | My educational institute encourages employees to participate in voluntary activities. |

| CSR12 | CSR | My educational institute policies encourage employees to develop their skills and careers. |

| CSR13 | CSR | The management of my educational institute primarily concerns with employees’ needs and wants. |

| CSR14 | CSR | My educational institute implements flexible policies to provide a good work-life balance for its employees. |

| CSR15 | CSR | The managerial decisions related to employees in my educational institute are usually fair. |

| EIC1 | EIC | My educational institute provides various formal training programs to improve the skills of employees. |

| EIC2 | EIC | My educational institute provides various informal training programs to improve the skills of employees. |

| EIC3 | EIC | My educational institute encourages employees to continue their education. |

| EIC4 | EIC | My educational institute supports employees who seek to acquire job-related skills. |

| EIC5 | EIC | My educational institute supports employees who want to get a work-related education. |

| EIC6 | EIC | Employees in my educational institute cooperate with each other. |

| EIC7 | EIC | Employees in my educational institute respect each other. |

| EIC8 | EIC | Employees in my educational institute trust each other. |

| AC1 | AC | I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this educational institute. |

| AC2 | AC | I enjoy discussing my educational institute with people outside it. |

| AC3 | AC | I really feel as if this educational institute’s problems are my own. |

| AC4 | AC | I feel emotionally attached to this educational institute. |

| AC5 | AC | This educational institute has a great deal of personal meaning for me. |

| TW1 | TW | I feel satisfied with my life. |

| TW2 | TW | I am close to my dream in most aspects of my life. |

| TW3 | TW | Most of the time, I do feel real happiness. |

| TW4 | TW | I am in a good life situation. |

| TW5 | TW | My life is very fun. |

| TW6 | TW | I would hardly change my current way of life in the afterlife. |

| TW7 | TW | I am satisfied with my work responsibilities. |

| TW8 | TW | In general, I feel fairly satisfied with my present job. |

| TW9 | TW | I find real enjoyment in my work. |

| TW10 | TW | I can always find ways to enrich my work. |

| TW11 | TW | Work is a meaningful experience for me. |

| TW12 | TW | I feel basically satisfied with my work achievements in my current job. |

| TW13 | TW | I feel I have grown as a person. |

| TW14 | TW | I handle daily affairs well. |

| TW15 | TW | I generally feel good about myself, and I’m confident. |

| TW16 | TW | People think I am willing to give and to share my time with others. |

| TW17 | TW | I am good at making flexible timetables for my work. |

| TW18 | TW | I love having deep conversations with family and friends so that we can better understand each other. |

| TA1 | TA | I admire my educational institute. |

| TA2 | TA | I respect my educational institute. |

| TA3 | TA | I feel reverence towards my educational institute. |

| TA4 | TA | I feel awe towards my educational institute. |

| TA5 | TA | I feel inspired by my educational institute. |

References

- Pagán-Castaño, E.; Maseda-Moreno, A.; Santos-Rojo, C. Wellbeing in work environments. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 115, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mynaříková, L.; Novotný, L. The current challenges of further education in ICT with the example of The Czech Republic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagán-Castaño, E.; Sánchez-García, J.; Garrigos-Simon, F.J.; Guijarro-García, M. The influence of management on teacher well-being and the development of sustainable schools. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Samad, S.; Mahmood, S. Sustainable pathways: The intersection of CSR, hospitality and the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, ahead of print, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buerkle, A.; O’Dell, A.; Matharu, H.; Buerkle, L.; Ferreira, P. Recommendations to align higher education teaching with the UN sustainability goals–A scoping survey. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2023, 5, 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S.F.; Wang, M.; Tang, M.; Saeed, A.; Iqbal, J. How toxic workplace environment effects the employee engagement: The mediating role of organizational support and employee wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farid, T.; Iqbal, S.; Saeed, I.; Irfan, S.; Akhtar, T. Impact of supportive leadership during COVID-19 on nurses’ well-being: The mediating role of psychological capital. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 695091. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; AlDhaen, E.; Siddique, I. Promoting the advocacy behavior of customers through corporate social responsibility: The role of brand admiration. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2023, 128, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roofe, C. Schooling, teachers in Jamaica and social responsibility: Rethinking teacher preparation. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 14, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. Education for Sustainable Development: Global progress and China’s experience. Chin. J. Urban Environ. Stud. 2019, 7, 1940001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y. Education development in China: Education return, quality, and equity. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Rafique, Z.; Zhou, R.; Asmi, F.; Anwar, M.A.; Siddiquei, A.N. Embedded philanthropic CSR in Digital China: Unified view of prosocial and pro-environmental practices. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 695468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.O. How CSV and CSR affect organizational performance: A productive behavior perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Concepción, A.; Gil-Lacruz, A.I.; Saz-Gil, I. Stakeholder engagement, Csr development and Sdgs compliance: A systematic review from 2015 to 2021. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Zehou, S.; Raza, S.A.; Qureshi, M.A.; Yousufi, S.Q. Impact of CSR and environmental triggers on employee green behavior: The mediating effect of employee well-being. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2225–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocean, C.G.; Nicolescu, M.M.; Cazacu, M.; Dumitriu, S. The role of social responsibility and ethics in employees’ wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: An examination of construct validity. J. Vocat. Behav. 1996, 49, 252–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, B.; Yu, J.; Chua, B.-L.; Lee, S.; Han, H. Relationships among emotional and material rewards, job satisfaction, burnout, affective commitment, job performance, and turnover intention in the hotel industry. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 21, 371–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisabeth, D.R.; Yuliastanti, R.; Suyono, J.; Chauhan, R.; Thakar, I. Affective commitment, continuance commitment, normative commitment, and turnover intention in shoes industry. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 2021, 25, 1937–1945. [Google Scholar]

- Clarence, M.; Devassy, V.P.; Jena, L.K.; George, T.S. The effect of servant leadership on ad hoc schoolteachers’ affective commitment and psychological well-being: The mediating role of psychological capital. Int. Rev. Educ. 2021, 67, 305–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shagholi, R.; Zabihi, M.R.; Atefi, M.; Moayedi, F. The consequences of organizational commitment in education. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 15, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Maltin, E.R. Employee commitment and well-being: A critical review, theoretical framework and research agenda. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ren, T.; Tang, W. Teachers in the top management team and corporate social responsibility. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlsrud, A. How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P.B. Decision latitude, job demands, and employee well-being. Work. Stress 1990, 4, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.; Johar, R.F.A.; Rasdi, R.M.; Alias, S.N. School as stakeholder of corporate social responsibility program: Teacher’s perspective on outcome in school development. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2014, 23, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cherian, J.; Ahmad, N.; Han, H.; de Vicente-Lama, M.; Ariza-Montes, A. Internal corporate social responsibility and employee burnout: An employee management perspective from the healthcare sector. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Luo, Y. Driving employee engagement through CSR communication and employee perceived motives: The role of CSR-related social media engagement and job engagement. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2024, 61, 287–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.M.; Chan, T.J.; Hasan, N.A.M. Mediating role of job satisfaction on internal corporate social responsibility practices and employee engagement in higher education sector. Contemp. Manag. Res. 2020, 16, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, G.C. Social behavior as exchange. Am. J. Sociol. 1958, 63, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikariparajuli, M.; Hassan, A.; Siboni, B. Csr implication and disclosure in higher education: Uncovered points. results from a systematic literature review and agenda for future research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas, C.; Mendes, L.; Marques, C.; Galvão, A. Exploring CSR’s influence on employees’ attitudes and behaviours in higher education. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2020, 11, 653–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Devos, G.; Li, Y. Teacher perceptions of school culture and their organizational commitment and well-being in a Chinese school. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2011, 12, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thien, L.M.; Lee, H.C. Is ‘the more the better’? Investigating linear and nonlinear effects of school culture on teacher well-being and commitment to teaching across school size. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2022, 74, 101176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lummis, G.W.; Morris, J.E.; Ferguson, C.; Hill, S.; Lock, G. Leadership teams supporting teacher wellbeing by improving the culture of an Australian secondary school. Issues Educ. Res. 2022, 32, 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Espasandín-Bustelo, F.; Ganaza-Vargas, J.; Diaz-Carrion, R. Employee happiness and corporate social responsibility: The role of organizational culture. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2021, 43, 609–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhodary, D.A. Exploring the relationship between organizational culture and well-being of educational institutions in Jordan. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albasu, J.; Nyameh, J. Relevance of stakeholders theory, organizational identity theory and social exchange theory to corporate social responsibility and employees performance in the commercial banks in Nigeria. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2017, 4, 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Galliani, E.M.; Vianello, M. The emotion of admiration improves employees’ goal orientations and contextual performance. Int. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 2, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.M.; Yam, K.C.; Koopman, J.; Ilies, R. Admired and disgusted? Third parties’ paradoxical emotional reactions and behavioral consequences towards others’ unethical pro-organizational behavior. Pers. Psychol. 2022, 75, 33–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; Ryu, H.B.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Han, H. From corporate social responsibility to employee well-being: Navigating the pathway to sustainable healthcare. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 1079–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cegarra-Navarro, J.G.; Martínez-Martínez, A. Linking corporate social responsibility with admiration through organizational outcomes. Soc. Responsib. J. 2009, 5, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Ahmad, N.; Sial, M.S.; Cherian, J.; Han, H. CSR and organizational performance: The role of pro-environmental behavior and personal values. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; AlDhaen, E.; Han, H.; Scholz, M. A CSR perspective to foster employee creativity in the banking sector: The role of work engagement and psychological safety. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, M.; Mulyadi, D.; Hananto, A.L.; Muhamad, N.H.N.; Teh, K.S.M.; Don, A.G. Empowering corporate social responsibility (CSR): Insights from service learning. Soc. Responsib. J. 2018, 14, 875–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieger, S.A.; Anderer, S.; Fröhlich, A.; Bäro, A.; Meynhardt, T. Too much of a good thing? On the relationship between CSR and employee work addiction. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 166, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.; Riedel, E.; Czens, F.; Petersohn, H.; Moellmann, H.L.; Schorn, L.; Rana, M. When Do Narcissists Burn Out? The Bright and Dark Side of Narcissism in Surgeons. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Liu, H.; Yao, M. Linking young teachers’ self-efficacy and responsibility with their well-being: The mediating role of teaching emotions. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 22551–22563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, M.; Fontana, E. Managing emotions in responsible management education courses and promoting the leadership of the Sustainable Development Goals. In Business Schools, Leadership and the Sustainable Development Goals; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, P.; Mittal, A. Meaningfulness of work and employee engagement: The role of affective commitment. Open Psychol. J. 2020, 13, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Malhotra, K.; Sharma, S.K. Moderation-mediation framework connecting internal branding, affective commitment, employee engagement and job satisfaction: An empirical study of BPO employees in Indian context. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2020, 12, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Johnson, M.J. Meaningful work and affective commitment: A moderated mediation model of positive work reflection and work centrality. J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 33, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivkin, W.; Diestel, S.; Schmidt, K.-H. Affective commitment as a moderator of the adverse relationships between day-specific self-control demands and psychological well-being. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 88, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Kumar, S.P. Organizational culture as a moderator between affective commitment and job satisfaction: Empirical evidence from Indian public sector enterprises. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2018, 31, 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraoui, K.; Bensemmane, S.; Ohana, M. Corporate social responsibility and employees’ affective commitment: A moderated mediation study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-G.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. A multilevel study of the relationship between csr promotion climate and happiness at work via organizational identification: Moderation effect of leader–followers value congruence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, N.; Scholz, M.; Ullah, Z.; Arshad, M.Z.; Sabir, R.I.; Khan, W.A. The nexus of CSR and co-creation: A roadmap towards consumer loyalty. Sustainability 2021, 13, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Cherian, J.; Ahmad, N.; Scholz, M.; Samad, S. Conceptualizing the role of target-specific environmental transformational leadership between corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behaviors of hospital employees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, C. Employee well-being in organizations: Theoretical model, scale development, and cross-cultural validation. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, A.S.; Wang, H.; Xin, K.R. Organizational culture in China: An analysis of culture dimensions and culture types. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2006, 2, 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweetman, J.; Spears, R.; Livingstone, A.G.; Manstead, A.S. Admiration regulates social hierarchy: Antecedents, dispositions, and effects on intergroup behavior. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 49, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; Arshad, M.Z.; Kamran, H.W.; Scholz, M.; Han, H. Relationship between corporate social responsibility at the micro-level and environmental performance: The mediating role of employee pro-environmental behavior and the moderating role of gender. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; Mahmood, A.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Han, H.; Scholz, M. Corporate social responsibility at the micro-level as a “new organizational value” for sustainability: Are females more aligned towards it? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Han, H.; Kim, M. Elevated emotions, elevated ideas: The CSR-employee creativity nexus in hospitality. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Naveed, R.T.; Scholz, M.; Irfan, M.; Usman, M.; Ahmad, I. CSR communication through social media: A litmus test for banking consumers’ loyalty. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ahmad, A.; Lewandowska, A.; Han, H. From screen to service: How corporate social responsibility messages on social media shape hotel consumer advocacy. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2024, 33, 384–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ahmad, A.; Siddique, I. Beyond self-interest: How altruistic values and human emotions drive brand advocacy in hospitality consumers through corporate social responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 2439–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Samad, S.; Han, H. Travel and Tourism Marketing in the age of the conscious tourists: A study on CSR and tourist brand advocacy. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2023, 40, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ahmad, N.; Jiang, M.; Arshad, M.Z. Steering the path to safer food: The role of transformational leadership in food services to combat against foodborne illness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 103958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappo-Abidemi, C.; Ogujiuba, K.K. Higher education institutions and corporate social responsibility: Triple bottomline as a conceptual framework for community development. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 8, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A. Corporate social responsibility and organizational psychology: An integrative review. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 180 | 43 |

| Female | 239 | 57 |

| Age Group | ||

| Under 30 | 85 | 20 |

| 30–40 | 157 | 37.5 |

| 41–50 | 109 | 26 |

| Over 50 | 68 | 16.5 |

| Experience | ||

| Less than 5 years | 119 | 28 |

| 5–10 years | 150 | 36 |

| More than 10 years | 150 | 36 |

| Educational Level | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 109 | 26 |

| Master’s degree | 195 | 46.5 |

| PhD or Doctorate | 115 | 27.5 |

| Type of Institution | ||

| Public sector | 251 | 60 |

| Private sector | 168 | 40 |

| Construct | Item Loading Range | Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | 0.920–0.955 | 0.966 | 0.966 | 0.973 | 0.879 |

| CSR | 0.788–0.940 | 0.983 | 0.983 | 0.984 | 0.830 |

| EIC | 0.823–0.879 | 0.947 | 0.948 | 0.956 | 0.730 |

| TA | 0.937–0.953 | 0.970 | 0.970 | 0.976 | 0.893 |

| TW | 0.762–0.821 | 0.957 | 0.959 | 0.961 | 0.622 |

| Variable | R Square | R Square Adjusted | f Squared AC | f Squared CSR | f Squared EIC | f Squared TA | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EIC | 0.463 | 0.460 | 0.654 | 1.144 | |||

| TA | 0.494 | 0.491 | 0.634 | 0.310 | 1.144 | ||

| TW | 0.264 | 0.258 | 0.048 | 0.048 | 0.076 | 1.224 |

| Variable | AC | CSR | EIC | TA | TW | HTMT AC | HTMT CSR | HTMT EIC | HTMT TA | HTMT TW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | 0.938 | 0.355 | 0.673 | 0.677 | 0.455 | 0.365 | 0.703 | 0.699 | 0.468 | |

| CSR | 0.911 | 0.333 | 0.417 | 0.244 | 0.345 | 0.426 | 0.247 | |||

| EIC | 0.855 | 0.617 | 0.444 | 0.644 | 0.460 | |||||

| TA | 0.945 | 0.475 | 0.485 | |||||||

| TW | 0.789 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Coefficient | Std. Dev. | T-Stats | p-Value | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | Accepted/Rejected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | CSR→TW | 0.321 | 0.070 | 4.586 | 0.000 | 0.193 | 0.372 | Accepted |

| H2 | CSR→EIC | 0.139 | 0.033 | 4.167 | 0.000 | 0.075 | 0.210 | Accepted |

| H4 | CSR→EIC→TW | 0.033 | 0.012 | 2.748 | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.064 | Accepted |

| H5 | CSR→TA | 0.288 | 0.043 | 6.729 | 0.000 | 0.211 | 0.371 | Accepted |

| H7 | CSR→TA→TW | 0.090 | 0.022 | 4.150 | 0.000 | 0.051 | 0.135 | Accepted |

| H8a | CSRxAC→EIC→TW | 0.011 | 0.008 | 1.496 | 0.135 | −0.001 | 0.030 | Rejected |

| H8b | CSRxAC→TA→TW | 0.041 | 0.014 | 3.046 | 0.002 | 0.018 | 0.071 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, S. From Global Goals to Classroom Realities: The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Promoting Teacher Wellbeing in Higher Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6815. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166815

Wu S. From Global Goals to Classroom Realities: The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Promoting Teacher Wellbeing in Higher Education. Sustainability. 2024; 16(16):6815. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166815

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Shixiao. 2024. "From Global Goals to Classroom Realities: The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Promoting Teacher Wellbeing in Higher Education" Sustainability 16, no. 16: 6815. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166815

APA StyleWu, S. (2024). From Global Goals to Classroom Realities: The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Promoting Teacher Wellbeing in Higher Education. Sustainability, 16(16), 6815. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166815