Psychosocial Risks in Non-University Teachers: A Comparative Study between Spain and Mexico on Their Occupational Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

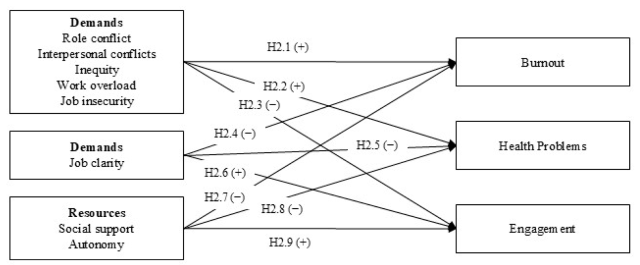

Objectives and Hypotheses

- Objective 1. Analyse psychosocial risks in Spanish and Mexican non-university teachers.

- Objective 2. Evaluate the relationships established between demand factors and resources as antecedents and burnout, health problems, and engagement as consequences in both countries.

- Objective 3. Analyse the moderating effect of the country on the relationships between demands, resources, and consequences.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Demands

2.4. Resources

2.5. Consequences

2.6. Procedure

- (1)

- Being a teacher at an institution other than a university.

- (2)

- Being actively working during the evaluation period.

- (3)

- Having signed the informed consent and the confidentiality agreement that is framed within the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

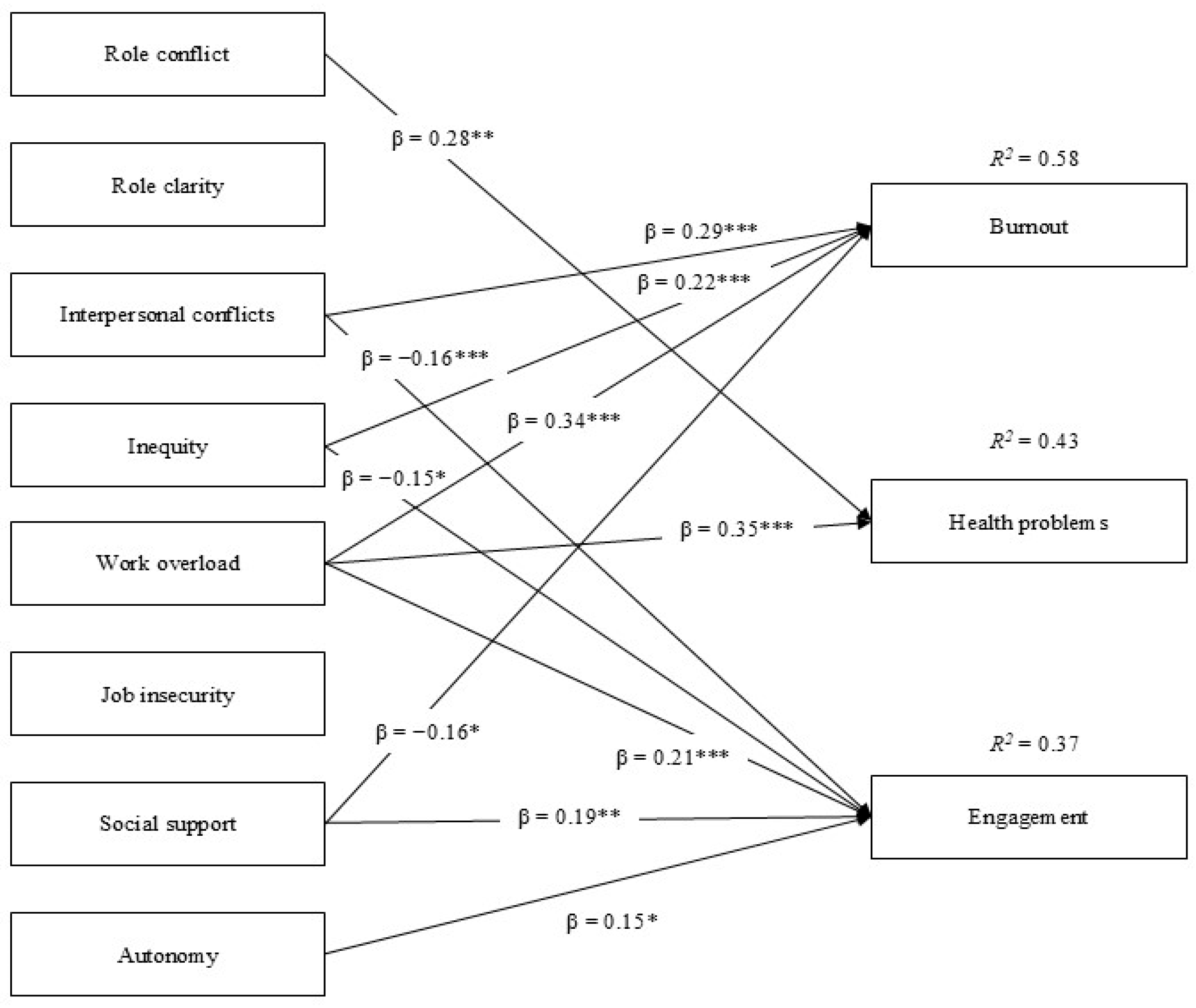

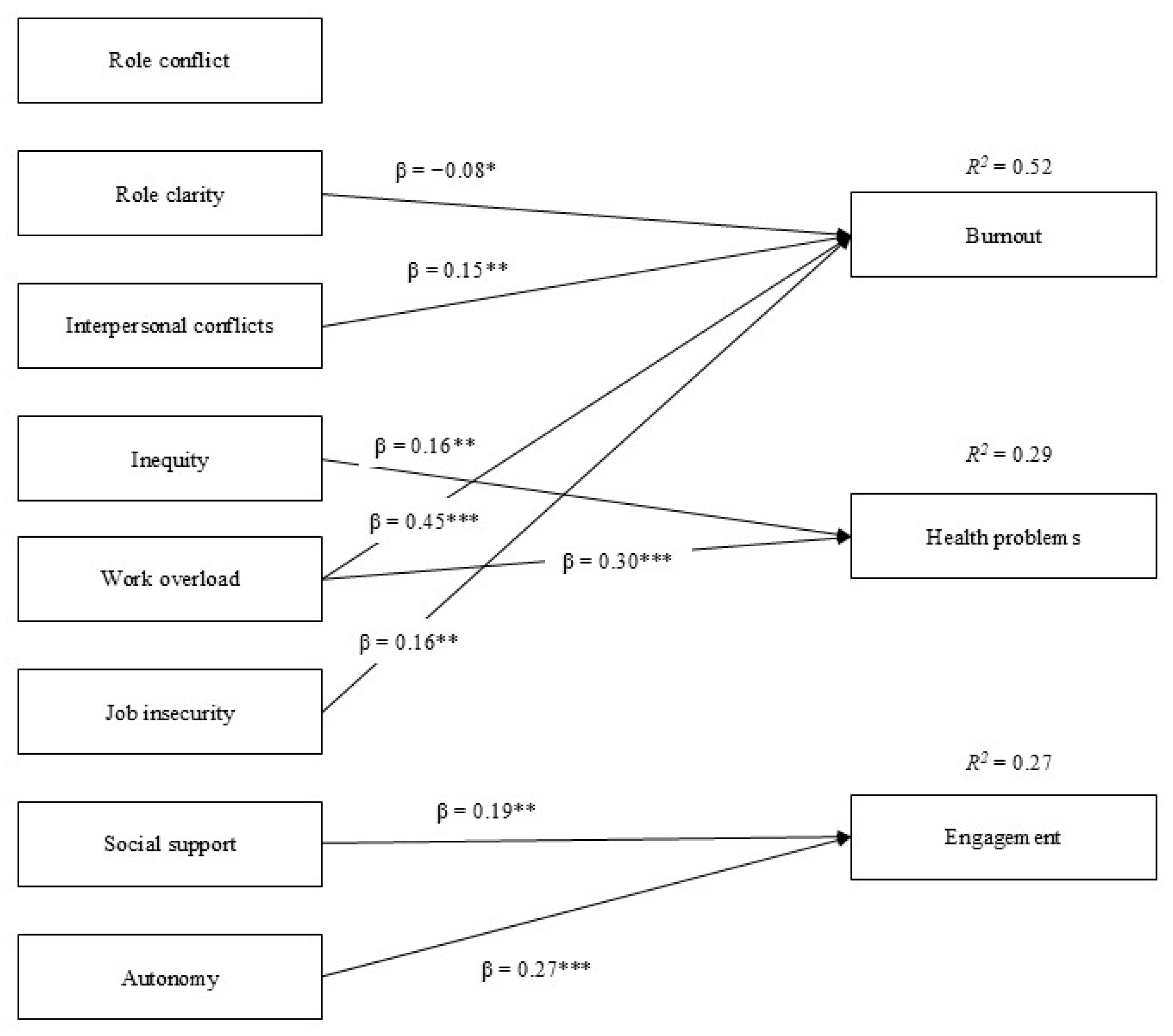

3.2. Reliability, Validity, and Relationship between the Variables

3.3. Moderating Effect of the Country on the Relationships between Demands, Resources, and Consequences

4. Discussion

4.1. Objective Analysis

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Conclusions

4.4. Implications and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Valencia-Contrera, M.; Rivera-Rojas, F. Psychosocial occupational risks: A proposed definition. Med. J. Chile 2023, 151, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (OSHA-EU). III Emerging Risks Survey. 2020. Available online: https://ketlib.lib.unipi.gr/xmlui/bitstream/handle/ket/945/Issue-2002-Developing-a-risk-prevention-culture-in-Europe.pdf?sequence=2 (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- National Institute of Safety and Health at Work (INSST). Mental Health and Work; National Institute of Safety and Health at Work (INSST): Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association (APA). 2023 Work in America Survey; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, J. Work Is Killing Us: How to Improve Occupational Health; LID Business Publishing: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa Cabrera, E.L. Psychosocial Risks and Quality of Work Life in Employees of Health Centers in Trujillo, 2023. [Final Degree Project, César Vallejo University]. Institutional Digital Repository of the César Vallejo University. 2023. Available online: https://repositorio.ucv.edu.pe/bitstream/handle/20.500.12692/137121/LaRosa_CEL-SD.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Uribe-Prado, J.F. Psychosocial, burnout and psychosomatic risks in public sector workers. Adm. Res. 2020, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Peñaherrera, M.; Merino-Salazar, P.; Benavides, F.G.; López-Ruiz, M.; Gómez-García, A.R. Occupational health in Ecuador: A comparison with surveys on working conditions in Latin America. Rev. Bras. Saúde Ocup. 2020, 45, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Production and Labor (MPyT). National Survey of workers on Conditions of Employment, Work, Health and Safety [ECETSS] 2018; Ministry of Production and Labor: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mengistie, B.A.; Azene, Z.N.; Haile, T.T.; Abiy, S.A.; Abegaz, M.Y.; Taye, E.B.; Alemu, H.N.; Demeke, M.; Melese, M.; Tsega, N.T.; et al. Work-related burnout and its associated factors among midwives working at public hospitals in northwest Ethiopia: A multi-centered study. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1256063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Sorensen, K.L.; Yim, F.H.K. Does the Job Satisfaction—Job Performance Relationship Vary Across Cultures? J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2009, 40, 761–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grum, B.; Kobal Grum, D. Concepts of social sustainability based on social infrastructure and quality of life. Facilities 2020, 38, 783–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeter, E.; Rad, D. Global life satisfaction and general antisocial behavior in young individuals: The mediating role of perceived loneliness in regard to social sustainability—A preliminary investigation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). Calculating the Cost of Work-Related Stress and Psychosocial Risks; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work: Bilbao, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, E.; Van Bergen, P. Teacher burnout during COVID-19: Associations with instructional self-efficacy but not emotion regulation. Teach. Teach. 2023, 29, 310–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Du, R. Psychological capital, mindfulness, and teacher burnout: Insights from Chinese EFL educators through structural equation modeling. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1351912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madigan, D.J.; Kim, L.E.; Glandorf, H.L.; Kavanagh, O. Teacher burnout and physical health: A systematic review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 119, 102173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havet, N.; Plantier, M. The links between difficult working conditions and sickness absences in the case of French workers. Labour 2023, 37, 160–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, K.P.; Aguinis, H. How to prevent and combat employee burnout and create healthier workplaces during crises and beyond. Bus. Horiz. 2022, 65, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Safety and Health at Work (INSST). Annual Report on Work Accidents in Spain 2022; National Institute of Safety and Health at Work: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Llorca-Pellicer, M.; Gil-LaOrden, P.; Prado-Gascó, V.J.; Gil-Monte, P.R. The role of psychosocial risks in burnout, psychosomatic disorders, and job satisfaction: Linear models vs a QCA approach in non-university teachers. Psychol. Health 2023, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sainz, M.; Moreno-Bella, E.; Torres-Vega, L.C. Perceived unequal and unfair workplaces trigger lower job satisfaction and lower workers’ dignity via organizational dehumanization and workers’ self-objectification. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 53, 921–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañavate, G.; Meneghel, I.; Salanova, M. The Influence of Psychosocial Factors according to Gender and Age in Hospital Care Workers. Span. J. Psychol. 2023, 26, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, A.; Bouillon-Minois, J.B.; Bagheri, R.; Pélissier, C.; Charbotel, B.; Llorca, P.M.; Zak, M.; Ugbolue, U.C.; Baker, J.S.; Dutheil, F. The influence of burnout on cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1326745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Y.M.; Voo, P.; Maakip, I. Psychosocial factors, depression, and musculoskeletal disorders among teachers. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Membrive-Jiménez, M.J.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Suleiman-Martos, N.; Velando-Soriano, A.; Ariza, T.; de la Fuente-Solana, E.I.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A. Relation between Burnout and Sleep Problems in Nurses: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erjavec, K.; Leskovic, L. Long-term healthcare professionals’ experiences of burnout and correlation between burnout and fatigue: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 36, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klopack, E.T.; Crimmins, E.M.; Cole, S.W.; Seeman, T.E.; Carroll, J.E. Social stressors associated with age-related T lymphocyte percentages in older US adults: Evidence from the US Health and Retirement Study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2202780119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Domínguez, V.; Gómez-Domínguez, T.; Navarro-Mateu, D.; Giménez-Espert, M.C. The Influence of COVID-19 and Psychosocial Risks on Burnout and Psychosomatic Health Problems in Non-University Teachers in Spain during the Peak of the Pandemic Regressions vs. fsQCA. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Rodríguez, V.; Maeso-González, E.; Gutiérrez-Bedmar, M.; García-Rodríguez, A. Psychosocial risk and job satisfaction in professional drivers. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 994358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Wijn, A.N.; van der Doef, M.P. Reducing Psychosocial Risk Factors and Improving Employee Well-Being in Emergency Departments: A Realist Evaluation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 728390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenção, L.G.; Sodré, P.C.; Gazetta, C.E.; da Silva, A.G.; Castro, J.R.; Maniglia, J.V. Occupational stress and work engagement among primary healthcare physicians: A cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2022, 140, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Monte, P.R. Work Well-Being, Stress at Work and Occupational Health. In Manual of Work Psychology; Gil-Monte, P., Prado-Gascó, V.J., Eds.; Pyramid: Buffalo, MN, USA, 2021; pp. 243–285. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek, R. Job demands, job decision latitude and mental strain: Implications for job design. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.; Theorell, T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity and the Reconstruction of Working Life; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Monte, P.R. (Coord.) Manual of Psychosociology Applied to Work and the Prevention of Occupational Risks; Pyramid: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar Fernández, F.X.; Lombardero Posada, X.M.; Méndez Fernández, A.B.; Murcia Álvarez, E.; González Fernández, A. Influence of role stress on Spanish social workers’ burnout and engagement: The moderating function of recovery and coping. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2023, 26, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alblihed, M.; Alzghaibi, H.A. The Impact of Job Stress, Role Ambiguity and Work–Life Imbalance on Turnover Intention during COVID-19: A Case Study of Frontline Health Workers in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennbrant, S.; Dåderman, A. Job demands, work engagement and job turnover intentions among registered nurses: Explained by work-family private life inference. Work 2021, 68, 1157–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Top, M.; Tekingunduz, S. The Effect of Organizational Justice and Trust on Job Stress in Hospital Organizations. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2018, 50, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickum, M.; Desrumaux, P. Burnout among lawyers: Effects of workload, latitude and mediation via engagement and over-engagement. Psychiatry Psychol. Law 2023, 30, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Domínguez, V.; Navarro-Mateu, D.; Gómez-Domínguez, T.; Giménez-Espert, M.C. How much do we care about teacher job insecurity during the pandemic? A bibliometric review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1098013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.P.; Huang, F.; Liang, Q.; Liao, F.Z.; Tang, C.Z.; Luo, M.L.; Lu, S.L.; Lian, J.J.; Li, S.E.; Wei, S.Q.; et al. Socioeconomic factors, perceived stress, and social support effect on neonatal nurse burnout in China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pressley, T.; Marshall, D.T.; Moore, T. Understanding teacher burnout following COVID-19. Teach. Dev. 2024, 28, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguayo-Estremera, R.; Membrive-Jiménez, M.J.; Albendín-García, L.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Romero-Bejar, J.L.; de la Fuente-Solana, E.I.; Cañadas, G.R. Analysing Latent Burnout Profiles in a Sample of Spanish Nursing and Psychology Undergraduates. Healthcare 2024, 12, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şahan, C.; Tur, M.B.; Demiral, Y. The Relationship Between Psychosocial Risks and Sleep Disorders in Health Care Workers. J. Turk. Sleep Med. 2020, 7, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, B.; Bardhoshi, G. Demands, resources, meaningful work, and burnout of counselors-in-training. Couns. Educ. Superv. 2022, 61, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inggamara, A.; Pierewan, A.C.; Ayriza, Y. Work–life balance and social support: The influence on work engagement in the Sixth European Working Conditions Survey. J. Employ. Couns. 2022, 59, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Exploring the impact of workload, organizational support, and work engagement on teachers’ psychological well-being: A structural equation modeling approach. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1345740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, Y.; Lv, H.; Jiang, R.; Zhao, P.; Zheng, X.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Mao, F. The prevalence and correlates of burnout among Chinese preschool teachers. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, I.; Martínez-Ramón, J.P.; Ruiz-Esteban, C.; García-Fernández, J.M. Latent profiles of burnout, self-esteem and depressive symptomatology among teachers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozoemena, E.L.; Agbaje, O.S.; Ogundu, L.; Ononuju, A.H.; Umoke, P.C.I.; Iweama, C.N.; Kato, G.U.; Isabu, A.C.; Obute, A.J. Psychological distress, burnout, and coping strategies among Nigerian primary school teachers: A school-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čecho, R.; Švihrová, V.; Čecho, D.; Novák, M.; Hudečková, H. Exposure to mental load and psychosocial risks in kindergarten teachers. Zdrav. Varst. 2019, 58, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douelfiqar, I.; el Madhi, Y.; Soulaymani, A.; el Wahbi, B.; el Faylali, H. Evaluation of Psychosocial Risks Among High School Teachers in Morocco. Int. J. Eng. Pedag. 2023, 13, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischlitzki, E.; Amler, N.; Hiller, J.; Drexler, H. Psychosocial Risk Management in the Teaching Profession: A Systematic Review. Saf. Health Work 2020, 11, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefi, M.; Abdullah, A.G.K. The impact of organizational stressors on job performance among academic staff. Int. J. Instr. 2019, 12, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANPE. Annual Report of the Teacher’s Ombudsman for the 2022/2023 Academic Year; ANPE: Murcia, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bottiani, J.H.; Duran, C.A.K.; Pas, E.T.; Bradshaw, C.P. Teacher stress and burnout in urban middle schools: Associations with job demands, resources, and effective classroom practices. J. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 77, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. Teachers in Europe: Careers, Development and Well-Being; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). TALIS 2018 Results (Volume II) Teachers and Heads of Educational Centers as Valued Professionals; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Vílchez, J.J. Influence of Transformational Leadership on the Development of Psychological Harassment at Work (Mobbing). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). UIS.Stat Massive Data Download Service. 2023. Available online: https://uis.unesco.org/bdds (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Barragan, L.F.G.Y. Violence in the school context in Guanajuato, Mexico. Int. J. Psychol. 2023, 58, 932–933. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.J.; Lu, C.Q.; Siu, O.L. Job insecurity and job performance: The moderating role of organizational justice and the mediating role of work engagement. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Real, T.J.; Díaz-Román, T.M.; Mendiri, P. Vocal Problems and Burnout Syndrome in Nonuniversity Teachers in Galicia, Spain. Folia Phoniatr. Logop. 2024, 76, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, A.J.C.; Escorza, Y.H. Adaptation of primary school teachers to distance classes and burnout. J. Psychol. Auton. Univ. State Mex. 2022, 11, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unda, S.; Hernández-Toledano, R.A.; García-Arreola, O.; Lozada, C.E. Psychosocial risk factors predictors of Burnout Syndrome (BTS) in high school teachers. Psychol. Inf. 2020, 119, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado-Gascó, V.; Gómez-Domínguez, M.T.; Soto-Rubio, A.; Díaz-Rodríguez, L.; Navarro-Mateu, D. Stay at home and teach: A comparative study of psychosocial risks between Spain and Mexico during the pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez-Espert, M.C.; Prado-Gascó, V.; Soto-Rubio, A. Psychosocial Risks, Work Engagement, and Job Satisfaction of Nurses During COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 566896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Monte, P.R. The UNIPSICO Battery: Psychometric properties of scales that evaluate psychosocial demand factors. Arch. Occup. Risk Prev. 2016, 19, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Elst, T.; de Witte, H.; de Cuyper, N. The Job Insecurity Scale: A psychometric evaluation across five European countries. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2014, 23, 364–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Monte, P.R.; CESQT. Questionnaire for the Evaluation of Burnout Syndrome due to Work. Manual (2nd ed.). TEA Editions. 2019. Available online: https://web.teaediciones.com/CESQT--CUESTIONARIO-PARA-LA-EVALUACION-DEL-SINDROME-DE-QUEMARSE-POR-EL-TRABAJO.aspx (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Shimazu, A.; Hakanen, J.; Salanova, M.; de Witte, H. An ultra-short measure for work engagement: The UWES-3 validation across five countries. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2019, 35, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farndale, E.; Beijer, S.E.; Van Veldhoven, M.J.; Kelliher, C.; Hope-Hailey, V. Work and organisation engagement: Aligning research and practice. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2014, 1, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0; Released 2020; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M. EQS 6 Structural Equations Program Manual; Multivariate Software, Inc.: Encino, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 4. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS. 2022. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Becker, J.M.; Cheah, J.H.; Gholamzadeh, R.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM’s most wanted guidance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.H.; Lo, M.C.; Razak, Z.; Pasbakhsh, P.; Mohamad, A.A. Resources confirmation for tourism destinations marketing efforts using PLS-MGA: The moderating impact of semi-rural and rural tourism destination. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, T.Y.; Seifried, C. Virtual interactions and sports viewing on social live streaming platforms: The role of co-creation experiences, platform involvement, and follow status. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 162, 113884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A First on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Aguirre, M.I.; Barriga Medina, H.R.; Campoverde Aguirre, R.E.; Melo Vargas, E.R.; Armijos Yambay, M.B. Job Motivation, Burnout and Turnover Intention during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Are There Differences between Female and Male Workers? Healthcare 2022, 10, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Jørgensen, M.B.; Milczarek, M.; Munar, L. Healthy Workers, Thriving Companies: A Practical Guide to Well-Being at Work; European Agency for Safety and Health at Work: Bilbao, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bergh, L.; Leka, S.; Zwetsloot, G. Tailoring psychosocial risk assessment in the oil and gas industry by exploring specific and common psychosocial risks. Saf. Health Work 2018, 9, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, L.; Truxillo, D.; Bodner, T.; Pytlovany, A.; Richman, A. Exploration of the impact of organizational context on a workplace safety and health intervention. Work Stress 2019, 33, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorca-Pellicer, M.; Soto-Rubio, A.; Gil-Monte, P.R. Development of Burnout Syndrome in non-university teachers: Influence of demand and resources variables. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 644025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saloviita, T.; Pakarinen, E. Teacher burnout explained: Teacher-, student-, and organization-level variables. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 97, 103221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Hernández, E.F. Vocation and burnout in Mexican teachers. Educ. XX1 2023, 26, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, V.G.; Perilla-Toro, L.E.; Hermosa, A.M. Health risk for university professors associated with occupational psychosocial risk factors. Univ. Psychol. 2019, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, A.M.; Derbis, R. Work Stressors and Intention to Leave the Current Workplace and Profession: The Mediating Role of Negative Affect at Work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, V.; Topa, G.; Beléndez, M. Organizational justice and work stress: The mediating role of negative, but not positive, emotions. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2019, 151, 109392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Dunn, R.; Amlôt, R.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. Social and occupational factors associated with psychological distress and disorder among disaster responders: A systematic review. BMC Psychol. 2016, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, A.; Eguchi, H.; Kachi, Y.; Tsutsumi, A. Perceived psychosocial safety climate, psychological distress, and work engagement in Japanese employees: A cross-sectional mediation analysis of job demands and job resources. J. Occup. Health 2023, 65, e12405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, T.; Nagata, T.; Odagami, K.; Nagata, M.; Adi, N.P.; Mori, K.; Matsuyama, A. Workplace Social Support and Work Engagement Among Japanese Workers: A Nationwide Cross-sectional Study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 65, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wielers, R.; Hummel, L.; van der Meer, P. Career insecurity and burnout complaints of young Dutch workers. J. Educ. Work 2022, 35, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masa, A.; Derzsi-Horváth, M.; Tobak, O.; Deutsch, K. Mental Health and Social Support of Teachers in Szeged, Hungary. Int. J. Instr. 2022, 15, 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okojie, G.; Ismail, I.R.; Begum, H.; Ferdous Alam, A.S.A.; Sadik-Zada, E.R. The Mediating Role of Social Support on the Relationship between Employee Resilience and Employee Engagement. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role conflict | 1.09 | 0.86 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0–4 |

| Role clarity | 3.26 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0–4 |

| Interpersonal conflicts | 0.67 | 0.55 | 0.00 | 2.67 | 0–4 |

| Inequity | 1.98 | 0.98 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0–4 |

| Work overload | 1.87 | 0.71 | 0.17 | 3.50 | 0–4 |

| Job insecurity | 1.71 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1–5 |

| Social support | 2.78 | 0.92 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0–4 |

| Autonomy | 2.65 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0–4 |

| Burnout | 1.07 | 0.70 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0–4 |

| Health problems | 1.15 | 0.82 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0–4 |

| Engagement | 3.92 | 0.85 | 1.67 | 5.00 | 1–5 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role conflict | 0.88 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 3.80 | 0–4 |

| Role clarity | 3.65 | 0.60 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0–4 |

| Interpersonal conflicts | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 2.67 | 0–4 |

| Inequity | 2.09 | 0.84 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0–4 |

| Work overload | 1.53 | 0.70 | 0.17 | 3.83 | 0–4 |

| Job insecurity | 1.39 | 0.66 | 1.00 | 4.20 | 1–5 |

| Social support | 2.54 | 0.95 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0–4 |

| Autonomy | 2.65 | 0.90 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0–4 |

| Burnout | 0.98 | 0.62 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0–4 |

| Health problems | 1.20 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 3.56 | 0–4 |

| Engagement | 3.94 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1–5 |

| Variable | Spain | Mexico | 1−β | t-Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | t | p | ||

| Role conflict | 1.09 (0.86) | 0.88 (0.67) | 0.87 | 3.05 | 0.002 |

| Role clarity | 3.26 (0.82) | 3.65 (0.60) | 0.99 | −5.49 | 0.000 |

| Interpersonal conflicts | 0.67 (0.55) | 0.45 (0.47) | 0.92 | 5.30 | 0.000 |

| Inequity | 1.98 (0.98) | 2.09 (0.84) | 0.63 | −1.17 | 0.245 |

| Work overload | 1.87 (0.71) | 1.53 (0.70) | 0.99 | 4.85 | 0.000 |

| Job insecurity | 1.71 (0.99) | 1.39 (0.66) | 0.96 | 3.11 | 0.002 |

| Social support | 2.78 (0.92) | 2.54 (0.95) | 0.85 | 2.79 | 0.006 |

| Autonomy | 2.65 (0.80) | 2.65 (0.90) | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.658 |

| Burnout | 1.07 (0.70) | 0.98 (0.62) | 0.66 | 1.10 | 0.274 |

| Health problems | 1.15 (0.82) | 1.20 (0.80) | 0.53 | −0.69 | 0.490 |

| Engagement | 3.92 (0.85) | 3.94 (0.87) | 0.51 | 0.26 | 0.799 |

| βSpain | βMexico | Δβ | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social support ➔ Engagement | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.999 |

| Social support ➔ Health problems | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.09 | 0.392 |

| Social support ➔ Burnout | −0.16 | −0.07 | −0.10 | 0.322 |

| Autonomy ➔ Engagement | 0.15 | 0.27 | −0.12 | 0.334 |

| Autonomy ➔ Health problems | −0.04 | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.565 |

| Autonomy ➔ Burnout | −0.04 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.773 |

| Role clarity ➔ Engagement | 0.04 | 0.11 | −0.07 | 0.558 |

| Role clarity ➔ Health issues | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.738 |

| Role clarity ➔ Burnout | −0.08 | −0.08 | 0.00 | 0.993 |

| Role conflict ➔ Engagement | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.890 |

| Role conflict ➔ Health problems | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.300 |

| Role conflict ➔ Burnout | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.463 |

| Interpersonal conflicts ➔ Engagement | −0.16 | 0.02 | −0.18 | 0.094 |

| Interpersonal conflicts ➔ Health problems | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.551 |

| Interpersonal conflicts ➔ Burnout | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.152 |

| Inequity ➔ Engagement | −0.15 | −0.05 | −0.10 | 0.423 |

| Inequity ➔ Health problems | −0.02 | 0.16 | −0.18 | 0.119 |

| Inequity ➔ Burnout | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.156 |

| Job insecurity ➔ Engagement | −0.03 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.663 |

| Job insecurity ➔ Health problems | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.743 |

| Job insecurity ➔ Burnout | −0.01 | 0.16 | −0.17 | 0.044 |

| Work overload ➔ Engagement | −0.21 | −0.16 | −0.05 | 0.760 |

| Work overload ➔ Health problems | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.05 | 0.698 |

| Work overload ➔ Burnout | 0.34 | 0.45 | −0.11 | 0.443 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanchis-Giménez, L.; Tamarit, A.; Prado-Gascó, V.J.; Sánchez-Pujalte, L.; Díaz-Rodríguez, L. Psychosocial Risks in Non-University Teachers: A Comparative Study between Spain and Mexico on Their Occupational Health. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166814

Sanchis-Giménez L, Tamarit A, Prado-Gascó VJ, Sánchez-Pujalte L, Díaz-Rodríguez L. Psychosocial Risks in Non-University Teachers: A Comparative Study between Spain and Mexico on Their Occupational Health. Sustainability. 2024; 16(16):6814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166814

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanchis-Giménez, Lucía, Alicia Tamarit, Vicente Javier Prado-Gascó, Laura Sánchez-Pujalte, and Luis Díaz-Rodríguez. 2024. "Psychosocial Risks in Non-University Teachers: A Comparative Study between Spain and Mexico on Their Occupational Health" Sustainability 16, no. 16: 6814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166814

APA StyleSanchis-Giménez, L., Tamarit, A., Prado-Gascó, V. J., Sánchez-Pujalte, L., & Díaz-Rodríguez, L. (2024). Psychosocial Risks in Non-University Teachers: A Comparative Study between Spain and Mexico on Their Occupational Health. Sustainability, 16(16), 6814. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16166814