The Optimization of Steam Generation in a Biomass-Fired Micro-Cogeneration Prototype Operating on a Modified Rankine Cycle

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- The use of a batch boiler dedicated to straw combustion as a heat source;

- To maintain heat as a main product of the system’s operation;

- To provide low investment costs.

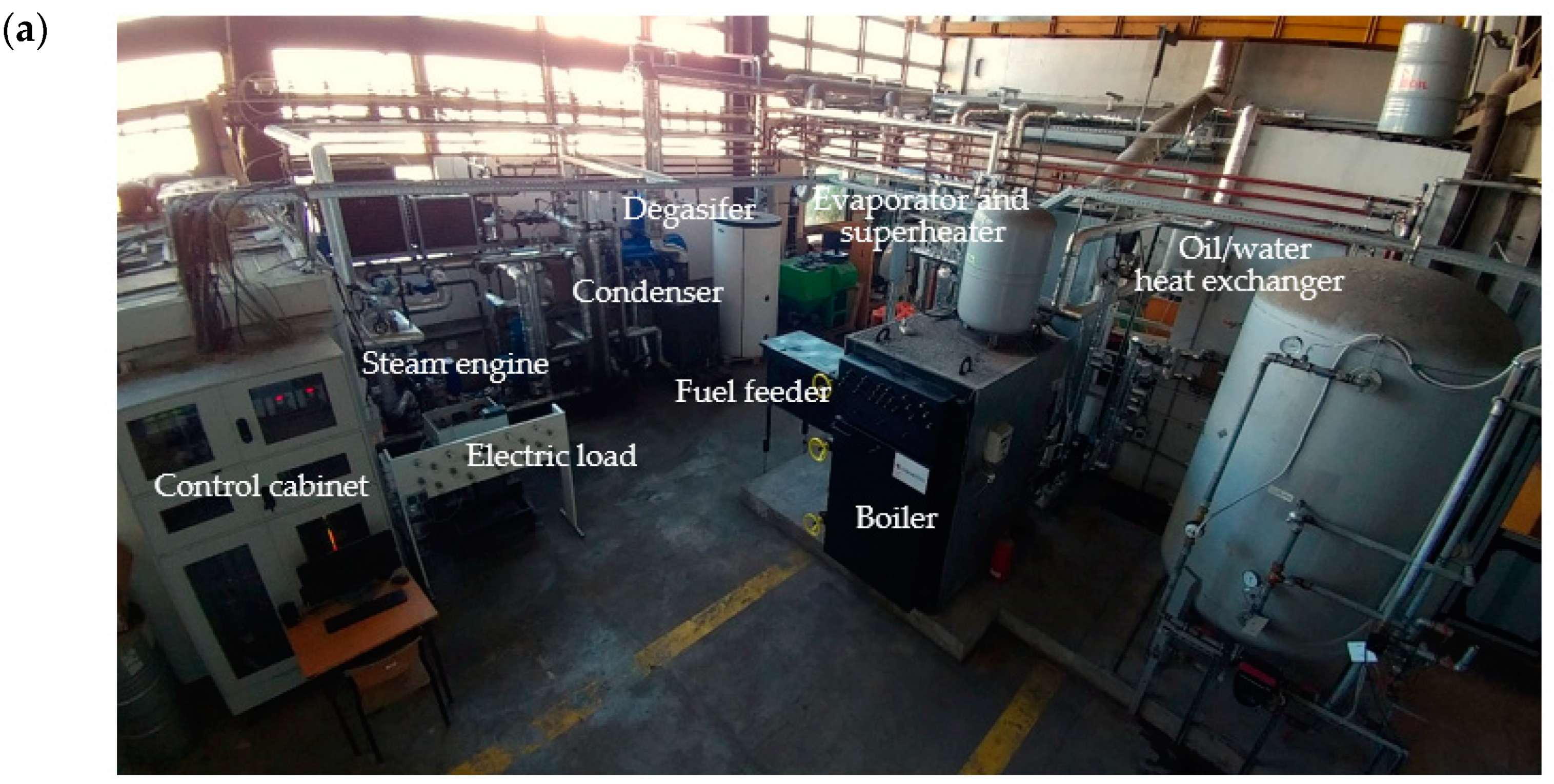

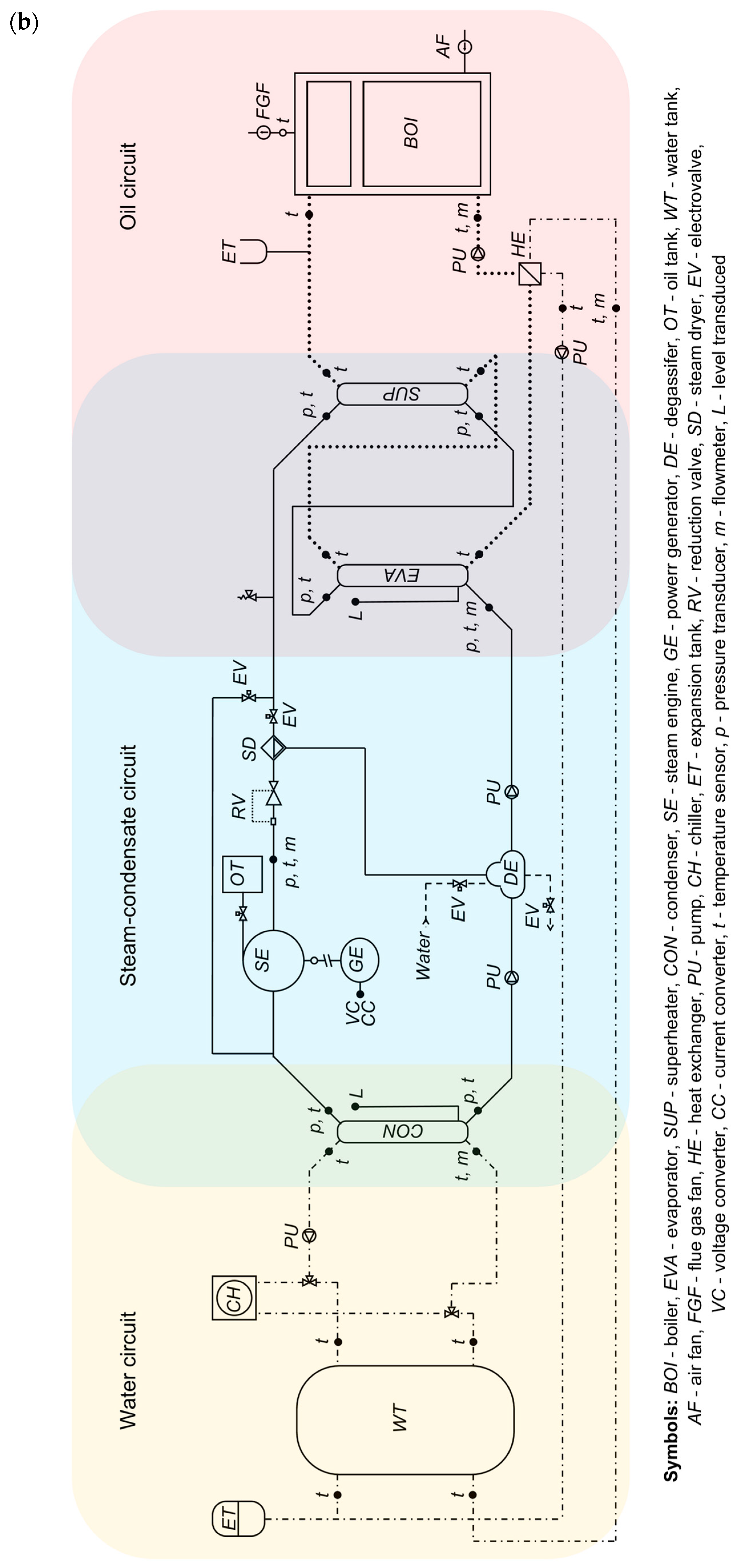

2.1. Construction of the Prototypical System

- Flue gas temperature at the outlet from the boiler;

- Thermal oil temperature (in the selected points) and flow;

- Condensate and steam temperature and pressure (at the selected points);

- The current and voltage generated in the power generator.

2.2. Experimental Procedure

2.3. Retrofitting Optimization of the System

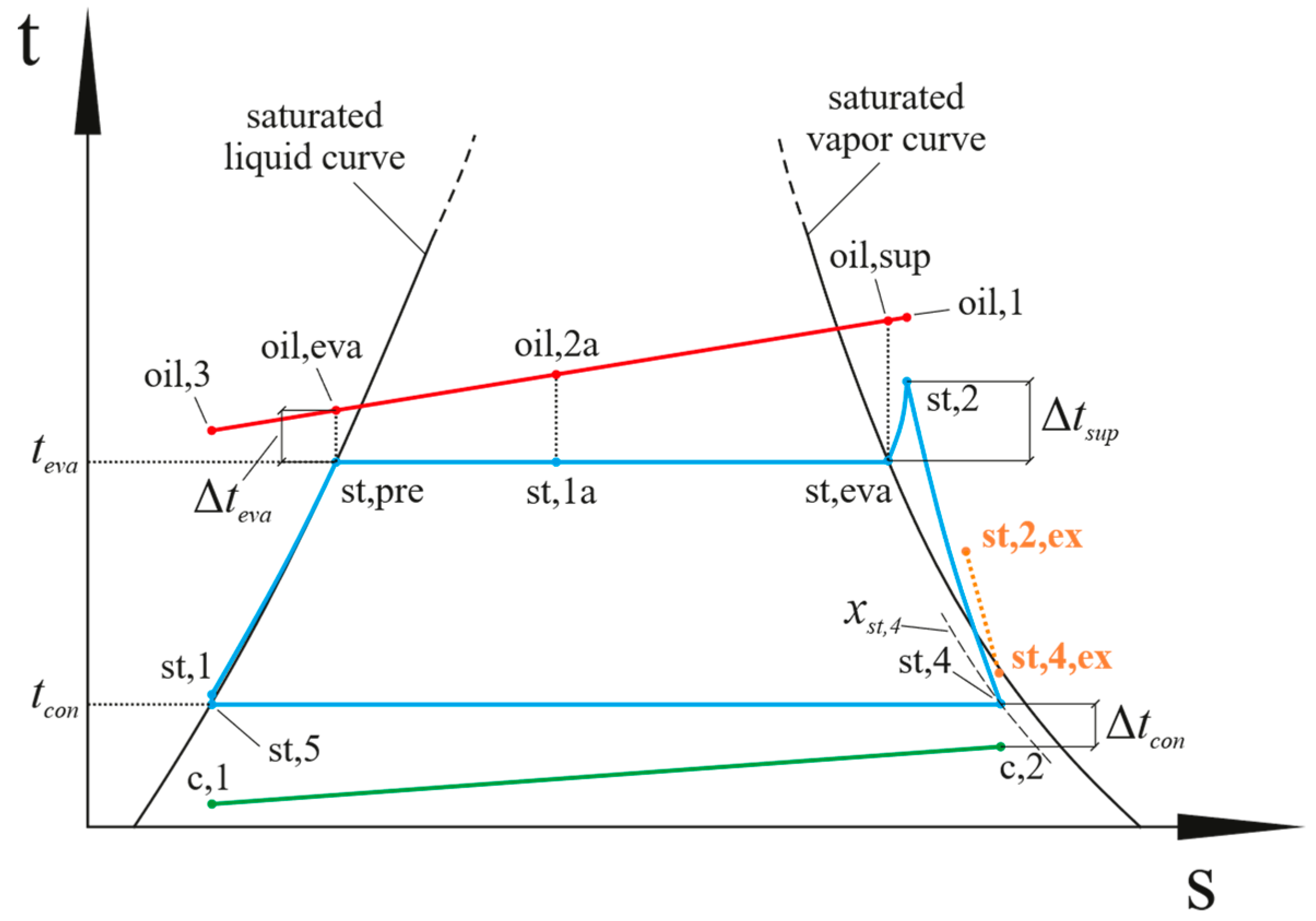

2.4. Thermodynamic Model

- Isobaric preheating (st,1–st-pre), evaporation (st,pre–st,eva), and superheating (st,eva–st,2) in the heat exchangers (“evaporator” and “superheater”);

- Irreversible expansion (st,2–st,4) in the steam engine;

- Isobaric condensation (st,4–st,5) in the condenser;

- Irreversible pressurizing (st,5–st,1) of the fluid in the pump.

2.5. Heat Transfer Analysis

- “Evaporator”

- “Superheater”

- “Condenser”

2.6. Input Parameters

2.7. Validation of the Model

2.8. Optimization Problem

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Steam Temperature and Pressure at the Outlet from the Superheater

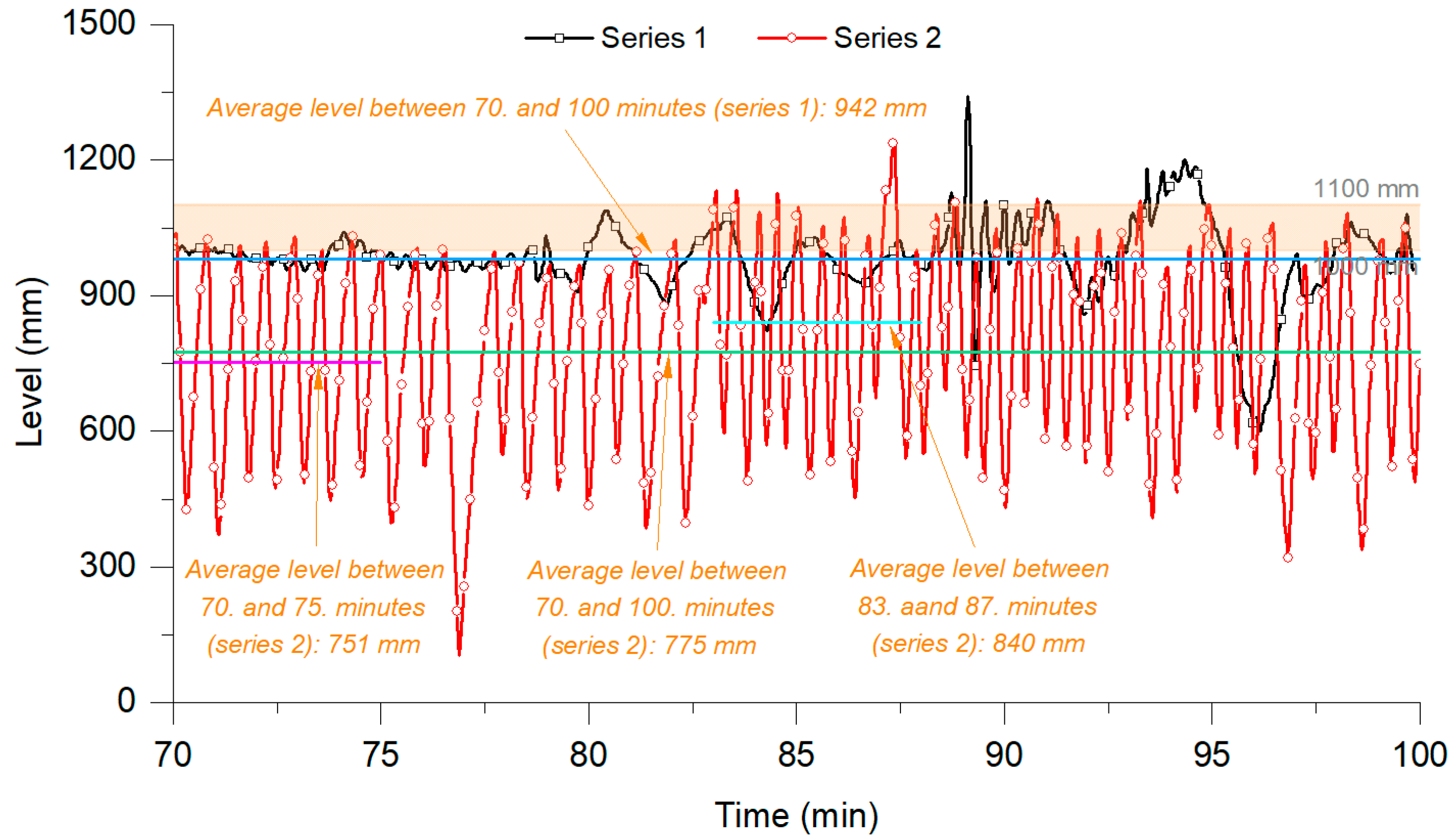

3.2. A Comparison of Continuous and Two-State Control of Condensate Pump Operation

3.3. The Efficiency of the Evaporator and Superheater

3.4. Condensate and Steam Temperature Distribution in the Steam–Condensate Circuit

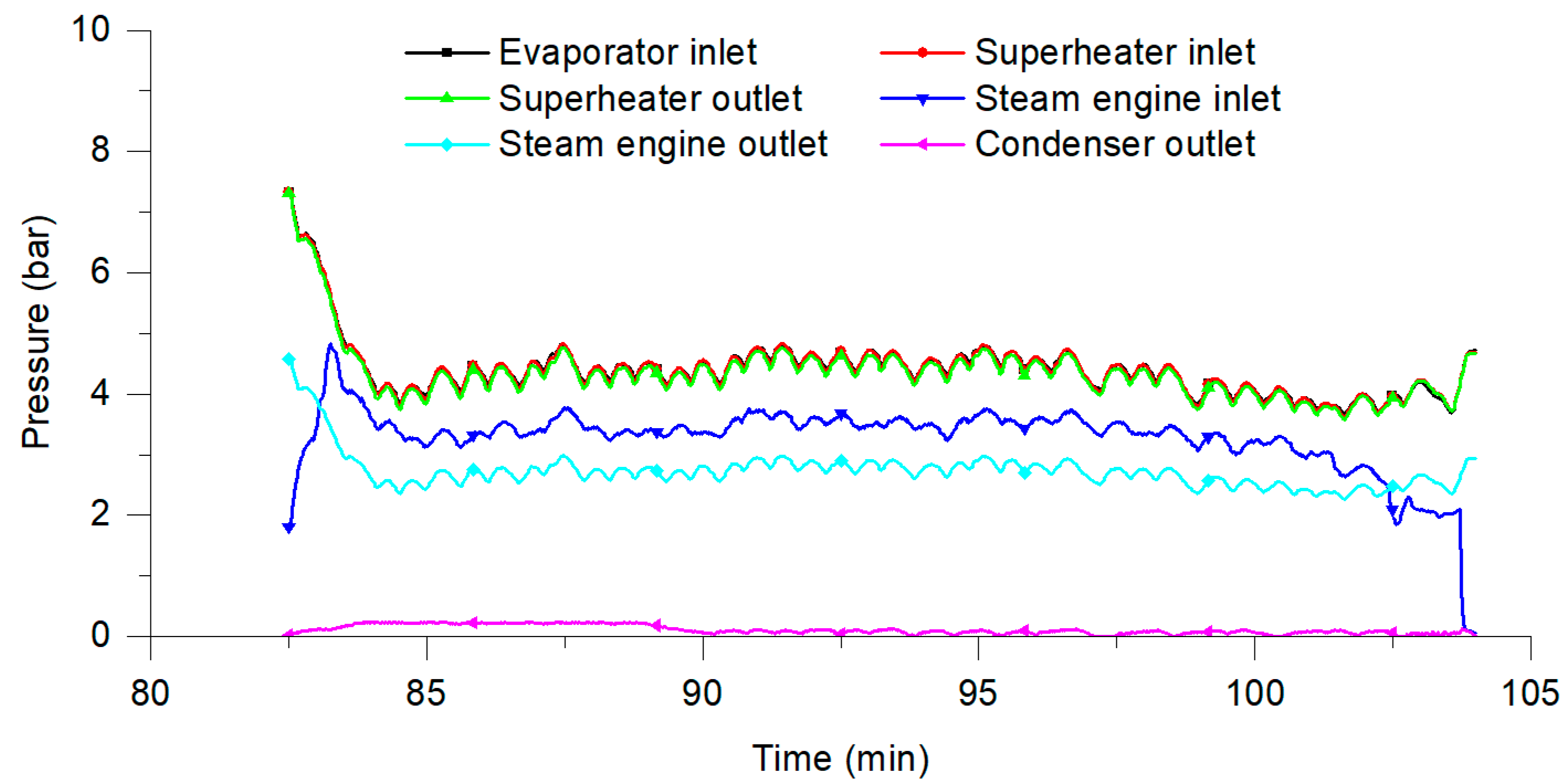

3.5. Condensate and Steam Pressure Distribution in the Steam–Condensate Circuit

3.6. Steam Temperature and Pressure Variations in the Steam Pipeline

3.7. Operating Characteristics of the Power Generator

3.8. Optimization Results

4. Conclusions

- The use of continuous control of condensate pump operation allowed providing a more stable condensate level in the evaporator. Between the 70th and 100th minutes of the combustion process, the average water level was 942 mm in the case of a continuous control and 775 mm in the case of a two-state control.

- In the considered time, the average superheater power related to its surface was over three times lower compared to the evaporator, and the efficiency of the superheater was calculated to be ca. 17 times lower than the evaporator efficiency.

- Significant drops in the steam temperature and pressure were observed in the pipeline between the superheater outlet and steam engine inlet: 52.3 K and 0.89 bar, respectively.

- The maximum obtained electrical power was only ca. 1.15 kWe. The main reason for such a low value was a very low power generator capacity, but other limitations were caused also by low steam pressure (which was a consequence of limitations in oil and steam temperature and steam bus construction, including large pipe capacity). Based on the observed system limitations, the required modifications were listed.

- Based on the suggested technological improvements, an original thermodynamic model incorporating new (evaporation ratio, ER) and well-established (superheating degree, SD) parameters was developed. Making use of the model, a retrofitting optimization of the system was conducted.

- The results of a retrofitting optimization of the system show that the electrical power output may be as high as 9.0 kWe.

- At the optimal operating conditions, the studied system was characterized by an energy utilization factor of 97.9%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| A | heat transfer area [m2] |

| ER | evaporation ratio [-] |

| c | specific heat capacity [kJ kg−1 K−1] |

| f | objective function [kWe] |

| h | specific enthalpy [kJ kg−1] |

| k | overall heat transfer coefficient [W m−2 K−1] |

| ṁ | mass flow rate [kg s−1] |

| P | power output [kW] |

| heat transfer rate [kW] | |

| SD | superheating degree [-] |

| s | specific entropy [kJ kg−1 K−1] |

| t | temperature [°C] |

| volume flow rate [L min−1] | |

| vector of decision variables | |

| x | steam quality [-] |

| Greek symbols | |

| Δt | temperature difference [K] |

| η | efficiency [%] |

| Sub- or superscripts | |

| CON | condenser |

| con | condensation |

| c | cooling water |

| E | evaporator |

| eva | evaporation |

| HX | heat exchanger |

| i | isentropic |

| in | inlet |

| log | logarithmic |

| m | mechanical |

| oil | oil |

| out | outlet |

| P | pump |

| PE | piston engine |

| pre | preheating |

| S | superheater |

| st | steam |

| sup | superheating |

| T | transposition |

References

- Ventura, C.; Wu, Q. Theoretical Evaluation of Photovoltaic Thermal Water Source Heat Pump, Application Potential and Policy Implications: Evidence from Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Statistics—An Overview—Statistics Explained. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Energy_statistics_-_an_overview#Final_energy_consumption (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Delgado-Plaza, E.; Carrillo, A.; Valdés, H.; Odobez, N.; Peralta-Jaramillo, J.; Jaramillo, D.; Reinoso-Tigre, J.; Nuñez, V.; Garcia, J.; Reyes-Plascencia, C.; et al. Key Processes for the Energy Use of Biomass in Rural Sectors of Latin America. Sustainability 2022, 15, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koval, V.; Laktionova, O.; Udovychenko, I.; Olczak, P.; Palii, S.; Prystupa, L. Environmental Taxation Assessment on Clean Technologies Reducing Carbon Emissions Cost-Effectively. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshikovhi, A.; Motaung, T.E. Technologies and Innovations for Biomass Energy Production. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentice d’Accadia, M.; Sasso, M.; Sibilio, S.; Vanoli, L. Micro-Combined Heat and Power in Residential and Light Commercial Applications. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2003, 23, 1247–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, A.D.; Leach, M.A. Cost-Effective Operating Strategy for Residential Micro-Combined Heat and Power. Energy 2007, 32, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmquist, A. Swedish Micro-CHP Solution—Externally Fired Microturbine System (Conference)|ETDEWEB. In Proceedings of the 2. World Conference on Pellets; Joenkoeping, Sweden, 30 May–1 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Alanne, K.; Saari, A. Sustainable Small-Scale CHP Technologies for Buildings: The Basis for Multi-Perspective Decision-Making. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2004, 8, 401–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, K.; Hayden, A.C.S. Integrated Thermoelectric and Organic Rankine Cycles for Micro-CHP Systems. Appl. Energy 2012, 97, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, P.; Casati, E.; Trapp, C.; Mathijssen, T.; Larjola, J.; Turunen-Saaresti, T.; Uusitalo, A. Organic Rankine Cycle Power Systems: From the Concept to Current Technology, Applications, and an Outlook to the Future. J. Eng. Gas. Turbine Power 2015, 137, 100801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Xu, C.; Liao, Z.; Du, X.; Wei, G.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y. A Review of Concentrated Photovoltaic-Thermal (CPVT) Hybrid Solar Systems with Waste Heat Recovery (WHR). Sci. Bull 2017, 62, 1388–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M.; Pandey, A.K.; Abd Rahim, N.; Tyagi, V.V.; Shahabuddin, S.; Saidur, R. Concentrated Photovoltaic Thermal Systems: A Component-by-Component View on the Developments in the Design, Heat Transfer Medium and Applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 186, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Shao, Y.; Li, J. A Biomass-Fired Micro-Scale CHP System with Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC)—Thermodynamic Modelling Studies. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 3985–3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champier, D. Thermoelectric Generators: A Review of Applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 140, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figaj, R.; Sornek, K.; Podlasek, S.; Żołądek, M. Operation and Sensitivity Analysis of a Micro-Scale Hybrid Trigeneration System Integrating a Water Steam Cycle and Wind Turbine under Different Reference Scenarios. Energies 2020, 13, 5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veringa, H.J.; Biomass, E. Advanced Techniques for Generation of Energy from Biomass and Waste; Energy Research Center of the Netherlands (ECN): Westerduinweg, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinavičienė, J. Assessment of Potential of Forest Wood Biomass in Terms of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszewska, D.; Olczak, P. Evaluation of Using Gas Turbine to Increase Efficiency of the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC). Energies 2020, 13, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sornek, K. Prototypical Biomass-Fired Micro-Cogeneration Systems—Energy and Ecological Analysis. Energies 2020, 13, 3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, E. Steam Power Plants. WIT Trans. State Art. Sci. Eng. 2008, 42, 99–139. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T. Methods of Improving the Efficiency of Thermal Power Plants. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1449, 12001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Goswami, D.Y.; Stefanakos, E.K. A Review of Thermodynamic Cycles and Working Fluids for the Conversion of Low-Grade Heat. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 3059–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drescher, U.; Brü, D. Fluid Selection for the Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) in Biomass Power and Heat Plants. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2006, 27, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.S.; Ribeiro, J.B.; Mendes, R.; Vaz, G.C.; André, J.C. ORC Based Micro-Cogeneration Systems for Residential Application—A State of the Art Review and Current Challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 92, 728–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badami, M.; Mura, M. Preliminary Design and Controlling Strategies of a Small-Scale Wood Waste Rankine Cycle (RC) with a Reciprocating Steam Engine (SE). Energy 2009, 34, 1315–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.K.; Lin, R. A Review of Engine Advanced Cycle and Rankine Bottoming Cycle and Their Loss Evaluations; SAE Technical Papers 830124; SAE: New Yor, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, G.; Shao, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Riffat, S.B. Experimental Investigation of a Biomass-Fired ORC-Based Micro-CHP for Domestic Applications. Fuel 2012, 96, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, G.; Bori, V.; Lazzaretto, A.; Toniato, G.; Danieli, P. Experimental Investigation of an Innovative Biomass-Fired Micro-ORC System for Cogeneration Applications. Renew Energy 2020, 161, 1226–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajs, J.; Mikielewicz, D.; Jakubowska, B. Performance of the Domestic Micro ORC Equipped with the Shell-and-Tube Condenser with Minichannels. Energy 2018, 157, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, E.; Nguyen, T.D.; Gan, Y.X.; Coronella, C.J.; Zuzga, M.; Li, M. Chemical Looping with Oxygen Uncoupling of Hydrochar in a Combined Cycle for Renewable and Low-Emission Power Generation. Digit. Chem. Eng. 2022, 5, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jradi, M.; Riffat, S. Experimental Investigation of a Biomass-Fuelled Micro-Scale Tri-Generation System with an Organic Rankine Cycle and Liquid Desiccant Cooling Unit. Energy 2014, 71, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ependi, S.; Nur, T.B. Design and Process Integration of Organic Rankine Cycle Utilizing Biomass for Power Generation. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 309, 012055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azish, E.; Assareh, E.; Azizimehr, B.; Lee, M. Exergoeconomic Analysis of an Integrated Electric Power Generation System Based on Biomass Energy and Organic Rankine Cycle. Aust. J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantoni, A.; Villarini, M.; Marcantonio, V.; Gallucci, F.; Cecchini, M. Performance Analysis of a Small-Scale ORC Trigeneration System Powered by the Combustion of Olive Pomace. Energies 2019, 12, 2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirillo, D.; Di Palma, M.; La Villetta, M.; Macaluso, A.; Mauro, A.; Vanoli, L. A Novel Biomass Gasification Micro-Cogeneration Plant: Experimental and Numerical Analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 243, 114349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fraia, S.; Figaj, R.D.; Massarotti, N.; Vanoli, L. An Integrated System for Sewage Sludge Drying through Solar Energy and a Combined Heat and Power Unit Fuelled by Biogas. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 171, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calise, F.; Capuozzo, C.; Carotenuto, A.; Vanoli, L. Thermoeconomic Analysis and Off-Design Performance of an Organic Rankine Cycle Powered by Medium-Temperature Heat Sources. Sol. Energy 2014, 103, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calise, F.; Dentice D’Accadia, M. Simulation of Polygeneration Systems. Energies 2016, 9, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The MathWorks Inc. MATLAB, Version R2019a; The MathWorks Inc.: Natick, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon, E.W.; Huber, M.L.; McLinden, M.O. NIST Standard Reference Database 23: Reference Fluid Thermodynamic and Transport Properties-REFPROP, Version 9.1; National Institute of Standards and Technology, Standard Reference Data Program: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- EMET-IMPEX. Available online: https://emet-impex.com.pl/ (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Boundy, B.; Diegel, S.W.; Wright, L.; Davis, S.C. Biomass Energy Data Book; Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, G.; Li, L.; Yang, Q.; Tang, B.; Liu, Y. Expansion Devices for Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) Using in Low Temperature Heat Recovery: A Review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 199, 111944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shengjun, Z.; Huaixin, W.; Tao, G. Performance Comparison and Parametric Optimization of Subcritical Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) and Transcritical Power Cycle System for Low-Temperature Geothermal Power Generation. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 2740–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzopoulou, M.A.; Simpson, M.; Sapin, P.; Markides, C.N. Off-Design Optimisation of Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) Engines with Piston Expanders for Medium-Scale Combined Heat and Power Applications. Appl. Energy 2019, 238, 1211–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, M.; Borsukiewicz, A. Multi-Objective Approach for Determination of Optimal Operating Parameters in Low-Temperature ORC Power Plant. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 200, 112075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, M.; Borsukiewicz, A.; Szopik-Depczynska, K.; Ioppolo, G. Determination of an Optimal Pinch Point Temperature Difference Interval in ORC Power Plant Using Multi-Objective Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 217, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzopoulou, M.A.; Lecompte, S.; De Paepe, M.; Markides, C.N. Off-Design Optimisation of Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) Engines with Different Heat Exchangers and Volumetric Expanders in Waste Heat Recovery Applications. Appl. Energy 2019, 253, 113442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsukiewicz-Gozdur, A. Pumping Work in the Organic Rankine Cycle. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2013, 51, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Wu, S.-Y.; Yi, T.-T.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.-R. Multi-Objective Optimization of Evaporation and Condensation Temperatures for Subcritical Organic Rankine Cycle. Energy 2015, 83, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Equipment | Range | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| flue gas temperature | K-type (NiCR-Ni) thermocouple sensors | −40–1200 °C | ±2.2 °C or ±0.75% |

| thermal oil temperature | Pt100 resistance sensors | −50–400 °C | tolerance ± 0.3 + 0.005 × [t] |

| thermal oil flow | ultrasonic flow meter | 0–50 kg/h | measuring error up to 2% |

| condensate and steam temperature | Pt100 resistance sensors | −50–400 °C | tolerance ± 0.3 + 0.005 × [t] |

| condensate and steam pressure | transducers | 0–16 bars | |

| the current generated in the power generator | the current transducers | 0–15 A | measuring error lower than ±0.5% |

| the voltage generated in the power generator | the voltage transducers | 0–400 V | measuring error lower than ±0.5% |

| Parameter | Series 1 | Series 2 |

|---|---|---|

| The amount of rectangular straw bales in the initializing load | 4 | 4 |

| The amount of additional rectangular straw bales added during the combustion process | 9 | 4 |

| Assumed flue gas temperature at the boiler’s outlet | 320–340 °C | 320–340 °C |

| Assumed thermal oil temperature at the boiler’s outlet | 190–210 °C | 190–210 °C |

| Assumed pressure of the steam at the superheater’s outlet | 8 | 8 |

| The way of control the condensate pump operation | Continuous control | Two-state control |

| Electric load setting | Constant | Various |

| toil,1 [°C] | [L min−1] | tc,1 [°C] | Δtcon [K] | Δtpinch,min [K] | ηi,PE [%] | ηm [%] | ηel [%] |

| 210 | 46.3 | 20.0 | 10.0 | 3.00 | 50 | 85 | 95 |

| ηi,P [%] | kpre [W m−2 K−1] | keva [W m−2 K−1] | ksup [W m−2 K−1] | kcon [W m−2 K−1] | AE,real [m2] | AS,real [m2] | ACON,real [m2] |

| 75 | 300 | 567 | 35.6 | 485 | 5.10 | 5.10 | 10.7 |

| Series No. | The Heat Generated in the Boiler and Transferred to the Oil MJ | Heat Transferred from Oil to Condensate and Steam MJ | Heat Transferred from Oil to Water MJ | Heat Losses in Pipes and Fittings MJ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 721.4 ± 14.6 | 458.8 ± 9.3 | 200.3 ± 4.1 | 62.3 ± 1.3 |

| 2 | 574.6 ± 11.6 | 314.1 ± 6.4 | 233.2 ± 4.7 | 27.3 ± 0.5 |

| Position | Evaporator | Superheater |

|---|---|---|

| The average temperature at the inlet to the heat exchanger [°C] | 55.0 | 168.7 |

| The average temperature at the outlet from the heat exchanger [°C] | 168.7 | 187.4 |

| The average pressure in the heat exchanger area (on the steam–condensate side) [bar] | 6.8 | 6.7 |

| Amount of condensate/steam [kg] | 55.0 | 55.0 |

| The amount of heat received from the oil [kWh] | 8.67 | 2.63 |

| The amount of heat transferred to the condensate/steam [kWh] | 6.43 | 0.12 |

| The average power in relation to the heat exchange surface [kW/m2] | 9.8 | 3.0 |

| Heat exchanger efficiency [%] | 74.2 | 4.5 |

| Element | Pressure Variations, Bars | Temperature Variations, K |

|---|---|---|

| Evaporator and superheater | −0.07 | +151.3 |

| Pipeline between superheater and steam engine | −0.89 | −52.3 |

| Steam engine | −0.71 | −46.5 |

| Decision Variables | Objective Function | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| teva [°C] | SD [-] | Δteva [K] | tcon [°C] | ER [-] | Pel [kWe] |

| 143 | 0.80 | 3.00 | 46.4 | 0.56 | 9.03 |

[kW] | [kW] | PP [kW] | Pnet [kW] | RCG [%] | εR [%] | ηR [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 103 | 91.4 | 0.02 | 9.01 | 0.22 | 97.9 | 10.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sornek, K.; Jankowski, M.; Borsukiewicz, A.; Filipowicz, M. The Optimization of Steam Generation in a Biomass-Fired Micro-Cogeneration Prototype Operating on a Modified Rankine Cycle. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010009

Sornek K, Jankowski M, Borsukiewicz A, Filipowicz M. The Optimization of Steam Generation in a Biomass-Fired Micro-Cogeneration Prototype Operating on a Modified Rankine Cycle. Sustainability. 2024; 16(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleSornek, Krzysztof, Marcin Jankowski, Aleksandra Borsukiewicz, and Mariusz Filipowicz. 2024. "The Optimization of Steam Generation in a Biomass-Fired Micro-Cogeneration Prototype Operating on a Modified Rankine Cycle" Sustainability 16, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010009

APA StyleSornek, K., Jankowski, M., Borsukiewicz, A., & Filipowicz, M. (2024). The Optimization of Steam Generation in a Biomass-Fired Micro-Cogeneration Prototype Operating on a Modified Rankine Cycle. Sustainability, 16(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010009