The goal of this study is to identify the evaluations of the users of the areas that have not yet been declared as urban transformation areas and who have not developed economic expectations about their residential units and their environment and to measure their loyalty to the place. After the literature survey, a 5-point Likert scale and a semi-structured questionnaire were first distributed among the users living in this neighborhood to investigate their satisfaction with housing and neighborhood, the use of open and semi-open spaces, and the perception of locality. The user survey was approved by the Bursa Uludağ University of Science and Engineering Sciences Research and Publication Ethics Committee on 27 September 2021 (number of session 2021-08, decision number 4). Then, field research was carried out by applying Delphi technique to the experts involved in housing redevelopment (designer, contractor, NGO, local government). In accordance with the data obtained from the literature survey and the questionnaire distributed among the neighborhood users, semi-structured open-ended questions were prepared for experts who take an active part in housing redevelopment. The expert survey was approved by Bursa Uludağ University of Science and Engineering Sciences Research and Publication Ethics Committee on 28 February 2022 (number of session 2022-02, decision number 2). In this study, all the participants, including users and experts who completed the questionnaire, were informed, consent was obtained, and the study was conducted according to ethical guidelines. The effects of physical, social, and economic dimensions on the scale of change occurring in housing units, neighborhoods, and urban spaces were questioned with the criteria that are effective in determining the scale. In this study, the expert opinions obtained through the Delphi technique and the approaches of residential unit users in the neighborhood were evaluated together. The main subjects of the research are the effect of scale on the formation of locality in the neighborhood, the effect of the physical scale of the housing units that make up the neighborhood on the social scale, the role of the user in determining appropriate local production scale, and the approach of experts involved in the housing redevelopment process to determine the scale.

This study aims to reveal the parameters determined according to the approaches of “users” and “experts” involved in housing production in determining the scale of housing production in accordance with local characteristics in housing redevelopment.

3.1. Bursa-Hürriyet Neighborhood

The Hürriyet Neighborhood located in Bursa was selected for the field study. Bursa is the fourth largest city in Türkiye in terms of population. Along with its history and geographical potential, it is a developing city with job creation due to industrialization, and its population is increasing rapidly with the (internal–external) immigrants it has received. The Hürriyet Neighborhood is one of the neighborhoods in Bursa where Turkish immigrants from the Balkans settled in the 1950s and where new immigrants have arrived over time through kinship and neighborhood ties. The neighborhood is characterized by low-rise buildings, and housing supply is met on a parcel-by-parcel basis [

37]. It can be said that it has preserved its general physical and socio-cultural character until now. Therefore, Hürriyet Neighborhood was found suitable for the research due to its local users and neighborhood characteristics.

Hürriyet Neighborhood is an old neighborhood close to the Organized Industrial Zone and Sanayi Street (

Figure 3). It was established in the early 1950s. In those years, the housing units were built by the state for citizens/relatives of people of Turkish origin (with ethnic structure) who migrated en masse from Bulgaria to Türkiye. Some of these houses, built with a grid plan, single floor, and out of adobe bricks and masonry, continue to exist today (

Figure 4). It is recognized as one of the tidiest neighborhoods of Bursa due to its orderly streets formed with grid plan [

38].

With the immigration policy implemented after 1950, the people of Turkish origin who came from Bulgaria about every 10 years continued to settle near their relatives or compatriots who had come before [

38]. Today, the Hürriyet Neighborhood is a clean, quiet, peaceful neighborhood where the majority of its inhabitants are former Bulgarian immigrants, and the users are happy [

38,

39]. In the neighborhood, where the social relations are observed to be strong and low-rise construction (3 floors on average) is widespread, new housing unit supply is carried out on the basis of parcels. In general, it can be said that the neighborhood has not changed much and has preserved its physical and socio-cultural character [

37]. In the 1960s, urban planning initiations around the city, including the Hürriyet Neighborhood, were implemented, through which parcels were created, accelerating the housing construction. Over time, users have tried to meet their needs with informal/illegal interventions, such as incorporating the garden into the house, adding rooms, or floors, etc. However, this situation has brought quality problems in terms of urban structuring (i.e., strength, layout, aesthetics, identity, etc.).

It is observed that the houses in Hürriyet Neighborhood do not rise as much as in other regions of Bursa. One of the reasons for this is that due to the existence of the Yunuseli Airport, which was established in the 1940s, there was a height restriction in and around the Hürriyet Neighborhood until recently. Later, the restrictions were lifted, and the way for high-rise construction was opened in the immediate vicinity (

Figure 5A). Another reason the houses in the neighborhood do not rise as much as in other regions is that the existing construction criteria and parcel sizes in the setting are relatively small. However, in recent years, some larger plots in the İstiklal and Adalet Neighborhoods, which were established in the same manner as the Hürriyet Neighborhood, have undergone functional changes. The areas in question have been converted into residential areas, and much taller buildings (approximately 10–15 stories) have been produced (

Figure 5B,C). It is expected that this situation will have an effect on the housing market, especially in the surrounding area, create additional pressure on other housing units in terms of conversion, and result in an upward trend. It is foreseen that this scale change in the region will affect social scales as well as physical and economic scales in the future.

The objective of this research’s field study is to identify the priorities and needs of local users in Hürriyet Neighborhood, which has been observed to have strong attachment and social characteristics but has experienced quality loss in the event of the reconstruction of housing. The aim is also to identify the potential of the area and produce results that focus on the utilization of this potential. In the survey conducted in Hürriyet Neighborhood, the environmental qualities of the residence and the neighborhood, user satisfaction, and perception of locality were investigated. The commitment of the existing users to the Hürriyet Neighborhood and how the users perceive the local scale were investigated. The Hürriyet Neighborhood serves as a hub and a commercial center for other nearby neighborhoods.

There are 765 buildings consisting of an average of 3 floors in the Hürriyet Neighborhood. While 723 buildings are being used for residential purposes, 20 of them have been granted construction registration certificates. Building registration certificate: The document to be created for the buildings that have been evaluated within the scope of zoning peace. The building registration certificate is a temporary document issued for the purpose of registering a building that was constructed illegally or in violation of permits before 31 December 2017 and does not provide additional rights in terms of zoning regulations and does not establish any acquired rights. It serves to document the zoning status of the building and its compliance with permits until it is made compliant or undergoes urban redevelopment [

42] within the scope of zoning peace. Zoning peace: The practice of registering buildings that are unlicensed or in violation of permits and attachments in an attempt to find a compromise between the state and the citizens as part of preparations for natural disaster risks, referred to as “zoning peace” by the public; it is regulated under the Zoning Law No 3194 [

42] regulation with an amendment published in the Official Gazette 2018. Since the municipality only detects illegal structures upon notification and complaint, the number and condition of illegal structures could not be determined (Bursa Metropolitan Municipality, 2022). According to 2020 data, the population of Hürriyet Neighborhood is 4732. One person per household was selected for the survey application. Since the average number of households was 3.5 in Türkiye (in 2020), the population group of the study was calculated to be 1352. In the survey study oriented at the users, a total of 65 participants were evaluated through a 2-month data collection process (October–November 2021), using a random selection method and face-to-face survey application. Due to the difficult conditions and the limited amount of time after the pandemic, 5% of the sample was made up. The questionnaire consists of 5 sections. The survey includes questions about user characteristics, housing characteristics and satisfaction, neighborhood characteristics and satisfaction, outdoor space use, locality, and scale assessment. An open-ended question was posed at the end of the survey. In this study, both quantitative and qualitative research methods were used together. The calculations were made using the Excel program. The reliability of this study was measured using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which is appropriate for Likert scale and individual responses, and the value was 0.85. Cronbach’s alpha is considered reliable when it is greater than 0.70 [

43].

In this study, while determining the criteria for the scale elements, studies on satisfaction and quality of life, belonging and loyalty, neighborhood, and other social relations at the scale of housing, housing environment, and neighborhood were analyzed. Demographic and socio-economic information was analyzed to determine the characteristics of the housing users. In addition, the age and condition of the housing, second house ownership, and the number of vehicles were questioned, and the economic status and economic conditions of the users were investigated within the scope of the subject. While investigating housing and neighborhood qualities and satisfaction, all criteria were examined, and the criteria that may be directly or indirectly related to local identity, belonging, and scale were determined and focused on the subject [

26,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52].

The female–male distribution of users participating in the survey is nearly equal. The majority of the participants are middle-aged or elderly. Although 65% of the participants were born in Bursa, they stated that they were of immigrant origin (Bulgaria). It was found that 77% of the participants have an income of less than TRY 6000, and almost all of them are in the lower-middle income group. Despite this, 78% of users live in their own homes (

Table 2).

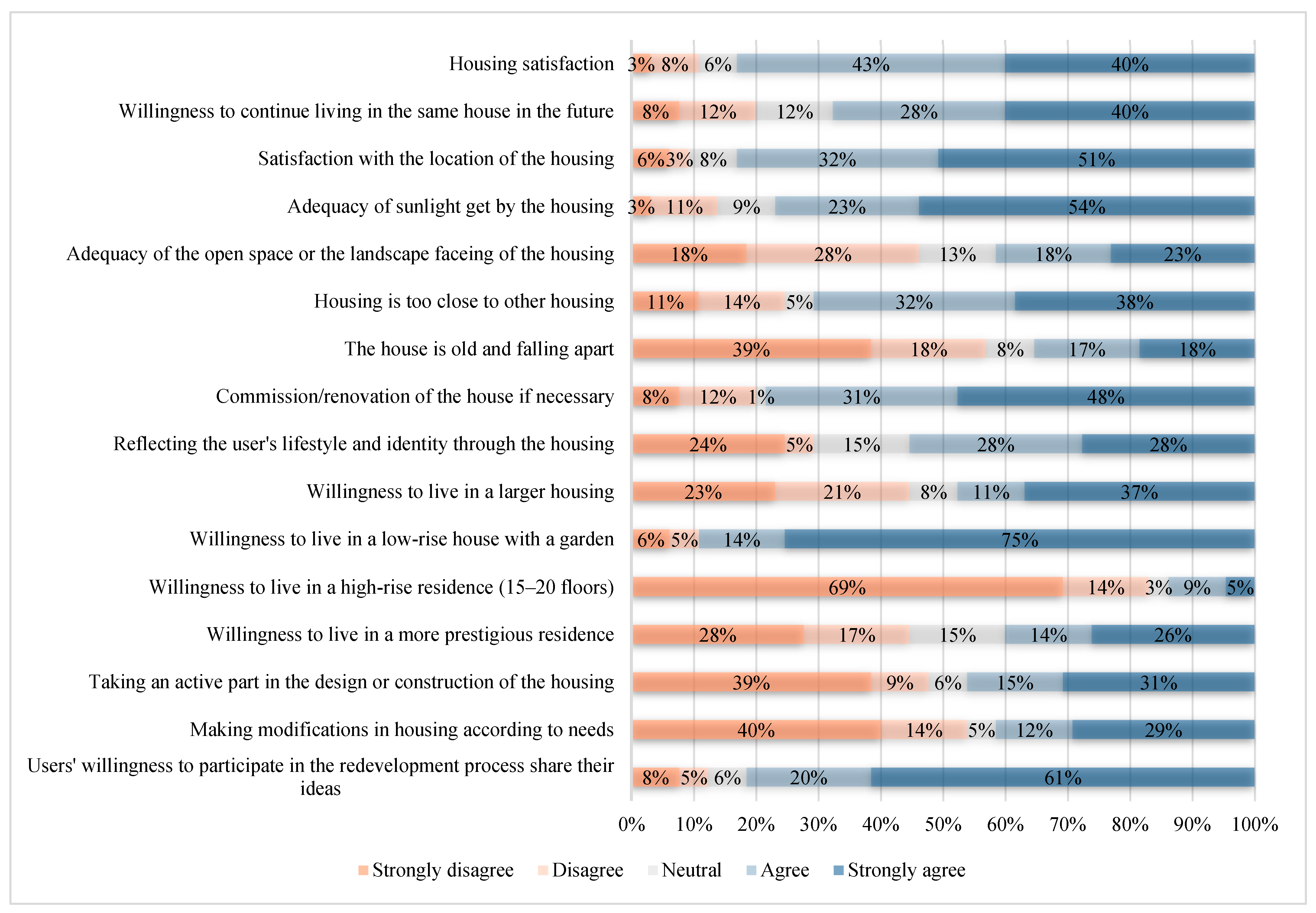

Users are satisfied with their housing (83%) and want to live in the same housing in the future. More than half of the users think that their housing reflects their lifestyle (56%). Almost half of the users want to live in a larger housing unit (48%). The percentage of those who want to live in low-rise housing with a garden is high (89%). However, the percentage of those who express that they want to live in higher-rise (15–20 floors) housing is relatively small (14%), while the percentage of those who want to live in more prestigious housing is remarkable (40%). Almost half of the users have taken part in the design or construction of their home (46%) and have made changes to their home in line with their needs (41%). If housing is to be reproduced, the percentage of those who want to participate in the process and present their ideas is quite high (81%) (

Figure 6).

Most of the users surveyed are satisfied with the neighborhood they live in (85%). The location of the neighborhood is quite advantageous in the city (96%). The neighborhood is considered to be authentic and attractive (63%) and, at the same time, lively (80%). It is stated that there is a parking problem (77%). Within walking distance of the neighborhood, daily needs are met (92%), and social facilities (education, health, shopping, religious facilities, etc.) are found to be partially sufficient (78%). Users stated that they meet their neighbors regularly (65%), help their neighbors (77%), and greet people they do not know (57%). Users think that their lifestyle is similar to that of the residents of the neighborhood (73%) and reflects themselves in terms of identity and culture (60%). The majority of users feel that they belong to the neighborhood (77%), and more than half of them want to live in the same neighborhood even if they move out of the housing they live in (55%). More than half of the users think the neighborhood has unique local characteristics (60%) (

Figure 7).

Figure 8 shows the purposes for which users utilize the open and common spaces in residence. It is worth noting that the use of the doorstep area is very common. The doorstep is mainly used for parking, children’s playground, eating and drinking, sitting, and chatting with neighbors. Other open and communal spaces are used quite widely for various purposes.

Figure 9 shows that the respondents to the questionnaire have stated that the low number of floors (75%) of the houses in the Hürriyet Neighborhood, the low population density (75%), and the fact that the residents have been living there for a long time (85%) are the main aspects that affect the local character of the neighborhood. In addition, it is observed that the fact that the neighborhood consists of low-rise residential buildings is effective in the formation of neighborhood relations and social ties (90%). This result was associated with the low density and the scale of the residential buildings. It is stated that transportation to social facilities (education, health, shopping, religious facilities, etc.) within walking distance is effective in the formation of the local characteristics of the neighborhood (87%). It is seen that the accessibility and reachability at the horizontal scale in the neighborhood support the liveliness and have an effect on the neighborhood character. Furthermore, it is stated that the continuity of the neighborhood’s residents has an essential role in the continuity of the locality (76%). A large portion of the users think that the production of high-rise residential buildings in the housing redevelopment process will have negative effects on the local characteristics (83%).

After the Hürriyet Neighborhood field research had been completed, the experts involved in the housing redevelopment processes were surveyed using the Delphi method. The Delphi method is a technique created by Dalkey and Helmer (1963) [

53] that allows for identifying the issues on which consensus is reached or not reached among the experts surveyed on a topic. This approach is prominent with the principle of “two views are better than one” and is considered reliable as it allows experts to express their ideas without influencing each other and to freely change their decisions. Basically, there are four features: privacy in participation, repetition, controlled feedback, and statistical analysis.

The Delphi method was implemented during the 3-month data collection period (March–May 2022) and was a result of face-to-face interviews conducted with experts in 3 separate rounds. In round 1, in-depth interviews were conducted with the experts, the data obtained were analyzed, and prominent issues were identified. The opinions of experts on the determined topics were evaluated, and the information obtained through the literature research was also used to create survey questions using a 5-point Likert scale. The prepared questions were directed to experts in the second round. The results of this stage were evaluated, and questions on which a consensus was reached and questions on which a consensus was not reached were determined. In the third round, each expert was provided the opportunity to re-evaluate and change their responses by returning their previous answers along with the overall averages to them. As a result of this round, the criteria on which consensus was reached and those on which consensus was not reached were determined by evaluating the results.

When identifying experts who play an active role in housing redevelopment, attention was paid to the fact that participants are located in Bursa, have previous urban regeneration experience, and have at least 10 years of experience. Although an equal number of men and women were sought, due to the majority of experts who met the criteria being men, equal representation was not possible. A total of 16 participants, consisting of 4 women and 12 men, were included. The characteristics of the expert participants, consisting of designers, contractors, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), and a local administration group, are shown in

Table 3.

The study sections using the Delphi method are shown in

Table 4. The first round of the survey distributed to expert participants consisted of open-ended questions. Each expert’s response was evaluated, and the prominent criteria were identified and grouped as topics. Arguments related to the criteria under these topics were determined, and the experts were surveyed again, twice, using a 5-point Likert scale.

This study evaluates the priorities section in the final part of the Delphi study that was conducted on the experts. In the priorities section, 16 criteria were determined under 4 titles, and expert participants were asked to rank these criteria according to their level of importance. Only the 3rd round results were evaluated. The top 5 priority criteria for the first 3 titles and the top 10 priority criteria for the last title were evaluated, compared, and interpreted together with the answers of the users of the Hürriyet Neighborhood.

3.1.1. The Causes of Problems in the Housing Redevelopment

Experts were asked to rank the criteria relevant to the topic according to their order of priority. The most important criterion was given 16 points, and the scoring continued in decreasing order, whereby the criterion not selected was given 0 points. The numbers included in the graphs are the sum of these scores, which are determined by each of the experts for one criterion.

In the priorities section, the first thing expected from expert participants was to rank the causes of the problems encountered in housing redevelopment according to their priorities (

Figure 10).

The causes of problems in the housing redevelopment, according to experts:

(1) Economic constraints: Economic effects increase production costs by raising material prices, making it difficult for middle- and low-income users to afford and purchase housing. As housing sales increase, the prices of rental houses also increase, and access to housing gradually becomes more difficult. Starting from the country scale, the economic constraint is an important criterion that affects all other sub-scales.

(2) Users’ expectations are focused on economic rent: Users in the Hürriyet Neighborhood have also complained that developers are profit-oriented. Profit generated in housing production leads to grievances when it is not shared rightly among the actors. According to expert participants, when housing is redeveloped, users should pay the difference in value or settle for a smaller housing unit as the property has gained economic surplus/additional value. The fact that users did not pay any money in some redevelopment projects in Bursa created the same expectation for users in other regions. When the fee or housing size cannot be agreed upon by and between the user and the contractor, the financial resources required for the contractor to start the development work cannot be created. This situation has slowed down the housing redevelopment. To create resources, the local government has granted the right to increase the floor area ratio by 0.50 in some areas, and the scale of housing after the urban transformation has increased by approximately 1.5 times. However, the issue that is usually ignored in this approach is the effect of the economic rent distribution conflict between the contractor and the user on the city and the case of social benefit. The most critical issue affecting the scale of the city is the sharing of economic rent.

(3) Inability to take comprehensive decisions at higher scales: Due to the fact that city plans are roughly created without collecting sufficient data and analysis with current advanced technology, attempts to solve problems happen later on the fly and with short-term resolutions.

(4) Local administration’s inability to bring actors together in the right way: Local administration is expected to create a viable model by assuming a certain type of regulatory role (i.e., game planner) and function as an arbitrator. The contractors, in particular, are critical of the local administration’s role in the market as a developer of its own, competing with the private sector. On the other hand, through this way, the housing prices in the market can be kept under some kind of control by the local administrations.

(5) Failure to ensure effective participation of actors and users in the process: What is expected from effective participation is that, in addition to determining the standard of living, habits, local characteristics, user needs, and wishes, users should play a role in the design and assume an active role in the decision process.

According to experts, the criterion “local characteristics and disregard of the user identity” ranked 13th among the problems experienced in the housing redevelopment, which is quite far behind. This either indicates that the experts who take an active part in the housing redevelopment do not have adequate sensitivity towards maintaining the local characteristics of the neighborhoods, or it shows that other values are prioritized before preserving the local characteristics.

3.1.2. The Necessary Criteria for Ensuring Social Sustainability from the Users’ Perspective

In the priorities section, the second thing expected from expert participants was to rank the criteria necessary for ensuring social sustainability from the user’s perspective according to their priorities (

Figure 11).

According to experts, the priority criteria for ensuring social sustainability from the user’s perspective are as follows:

(1) Creating common spaces and interfaces in a proper manner for the living culture: It is observed that the use of open and shared spaces (i.e., doorstep, garden, courtyard, terrace, and balcony) is widespread among the users in the Hürriyet neighborhood (see

Figure 8). Especially in settlements where the climate is mild and the users are culturally familiar with the street, it is important to create common areas and interfaces to ensure social sustainability.

(2) Continuing to live in the same place and with former neighbors: Users think that the continuity of neighborhood residents is important for the continuation of locality in the housing redevelopment (75%) (see

Figure 9). The state of being neighborly and familiar in old and established neighborhoods is also considered valuable by experts. For the continuity of the locality, the existence of the current user must be preserved.

(3) Increasing transportation and accessibility opportunities: Users in the Hürriyet neighborhood have expressed that the location of the neighborhood within the city is advantageous (97%), and public transportation is sufficient. Users have stated that vehicles are dense, and there is a shortage of parking spots in the neighborhood (77%). About half of the users responded positively to the suggestion that the neighborhood they live in is suitable for bicycle use (56%) and the suggestion that the neighborhood they live in is suitable for stroller and wheelchair use (51%) (see

Figure 7). The Hürriyet Neighborhood has a flat topography; thus, it is suitable for cycling. Bicycle use is also widespread in the cultural/habitual sense. However, it is necessary to rearrange narrow streets and sidewalks, create bicycle paths and signs, and make floor materials suitable for accessible transportation (

Figure 12). According to experts and users, increasing transportation and accessibility opportunities is essential for social sustainability.

(4) Users being able to find traces of their identity and former neighborhood: Users in the Hürriyet Neighborhood also think that the neighborhood reflects them in terms of identity and culture (60%), their lifestyle is similar to other neighborhood residents (72%), and the neighborhood has unique and local characteristics (60%) (see

Figure 7). Users have described these local characteristics as follows: the Hürriyet Neighborhood is calm, safe, clean, and tidy; the neighbor relations and cooperation between the residents remain; and the social relations are strong. In addition, the use of low-rise houses, gardens, and terraces is widespread, and certain cultural habits continue, such as winter food preparation at home, etc. The green areas around the neighborhood (agricultural and recreational areas) are considered valuable. It has been stated that squares named after state officials and used as meeting places that carry spiritual meaning should be preserved within the neighborhood. It has also been emphasized that the function of the commercial axes that are widely used should be preserved in order to continue social behaviors and living habits. Keeping the social memory alive and transferring some local features to the new settlement was considered important by both experts and users in terms of social sustainability.

(5) Economic accessibility: In particular, unaffordable apartment maintenance fees and rental prices cause users to leave their residential units, which is seen as an existential problem in ensuring social sustainability.

3.1.3. Features That a Neighborhood Unit Should Have after Housing Redevelopment

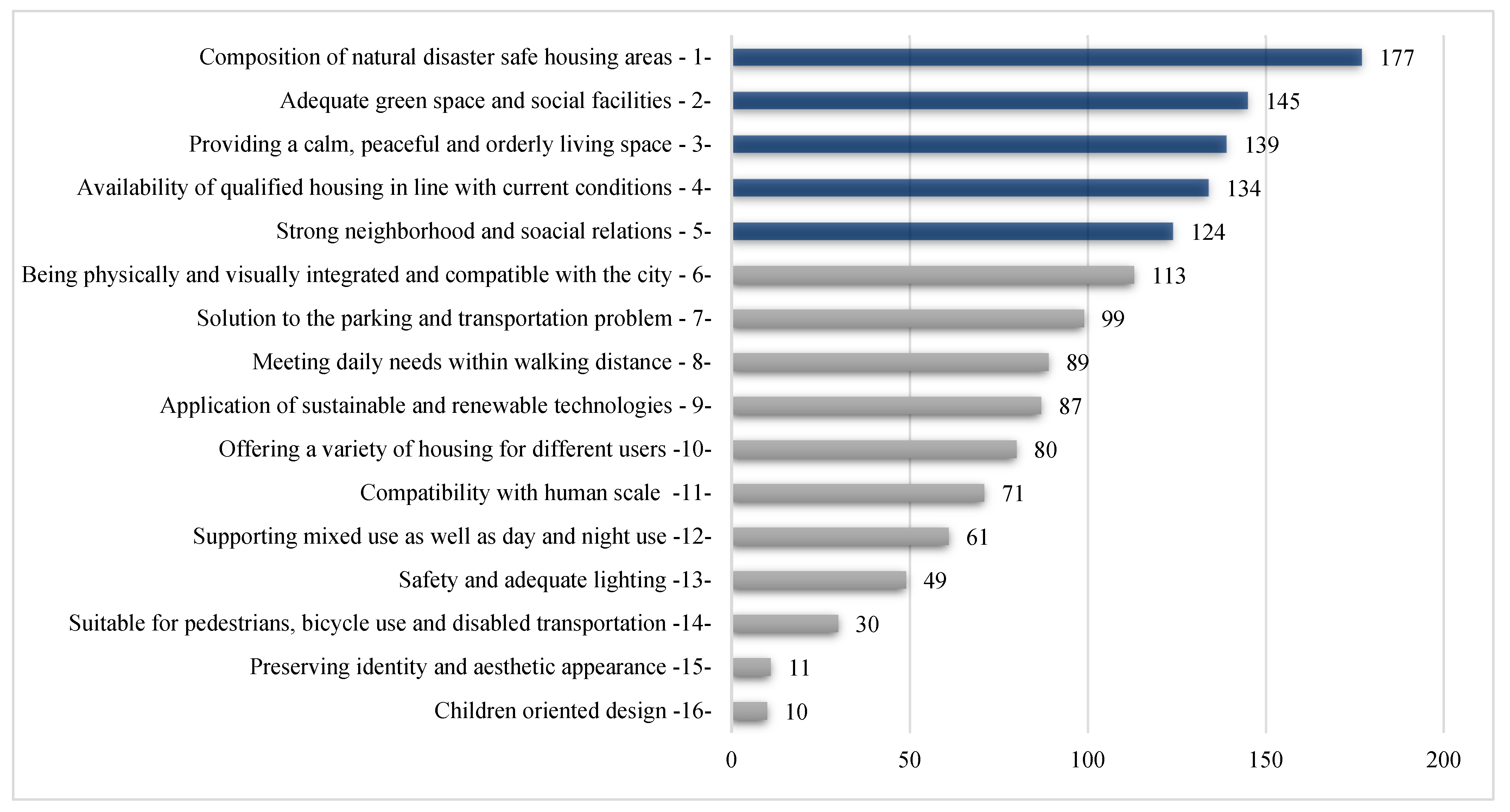

Thirdly, the expert participants were asked to rank the criteria defining the characteristics that a neighborhood unit should have after housing redevelopment (

Figure 13).

Features that a neighborhood unit should have after housing redevelopment:

(1) Disaster-safe housing areas: A portion of users in the Hürriyet Neighborhood have stated that they have made modifications to their housing according to their needs (41%). Although it is seen that housing modifications yield changes within the interior and result in illegal interventions, such as building additional floors, the data on illegal constructions is insufficient. After the Great Marmara earthquake of 1999, zoning regulations were updated, and new rules for structural safety were established. Recently, it has been observed that users have redeveloped their residences at the parcel level by reaching agreements with various contractors. It can be assumed that these structures were built according to the new legislation and are safer in terms of natural disasters. The presence of old, inferior-quality housing and crumbling areas in the Hürriyet Neighborhood that were built prior to 1999 without any input from architectural and engineering services makes the redevelopment of housing necessary (

Figure 14).

(2) Sufficient green spaces and social facilities: One of the biggest problems in our cities, where population and housing density are increasing, is the insufficiency of social facilities such as qualified green spaces, recreational facilities, schools, and health centers. The users in Hürriyet Neighborhood are of the opinion that the social facilities in the neighborhood (i.e., educational facilities, health centers, shopping malls, prayer rooms, etc.) are sufficient (78%). It has been verbally stated that the health sector is considered inadequate. The percentage of those who think that there are enough children’s playgrounds (49%) and enough green spaces (38%) in the neighborhood is quite small (see

Figure 7). Since the only children’s playgrounds and recreational areas (

Figure 15A,B) in the neighborhood are insufficient at the neighborhood level, other parks and recreational areas in nearby neighborhoods are used in most cases.

(3) Providing a calm, peaceful, and orderly living space: The percentage of users in the Hürriyet Neighborhood who think that the neighborhood is lively and energetic (80%) and those who think that the neighborhood is dense and crowded (67%) is higher (see

Figure 7). The reason for this density is that many people from the surrounding areas visit the Hürriyet Neighborhood to shop at the stores and use the social facilities in the neighborhood. The percentage of those who responded that they can meet their daily needs within walking distance in the neighborhood where they live (92%) is quite high. There is a high percentage of users who feel safe walking around the neighborhood (70%) and those who say that children can walk to school alone (71%) (see

Figure 7). The perception of security in the neighborhood is high, and the crime rate is low. It argued that a complex, noisy, unsafe, and stressful life continues in areas where neighborhoods host an increasing number of immigrants, especially in areas where low-income groups live and illegal construction is intense. Since it is the fundamental right of every urban person to live in healthy and high-quality environments, improving these conditions is important for ensuring the health and well-being of the urban population.

(4) Production of housing that is suitable and of good quality to current conditions: Especially in neighborhoods that have existed for a long time, the houses may lose their structural integrity over time and become unable to meet the needs of today, even if they were initially produced with architectural and engineering services according to the conditions of the time; therefore, it is necessary to rebuild them. On the other hand, it is indisputable that illegal structures built without technological production, legal regulation, or supervision should be renewed. Among the users of the Hürriyet Neighborhood, the percentage of those who say that their housing unit is old and crumbling down (35%) is remarkable. The percentage of those who say that they have made or commissioned maintenance or renovation works in the housing unit they live in when necessary (79%) is high. The percentage of those who say that they have taken active part in the design or construction of the housing they live in (46%) and those who say that they have made modifications to their housing unit according to their needs (41%) is important (see

Figure 6). It is seen that the users in the Hürriyet Neighborhood have adapted their housing units.

(5) Strong neighborhood and social relations: Users in the Hürriyet Neighborhood regularly meet with their neighbors (65%). Those who help their neighbors constitute 77%, and those who greet strangers in the neighborhood constitute 57% (see

Figure 7). Neighborhood and other social relations create a sense of security and strengthen the sense of belonging and loyalty to the neighborhood.

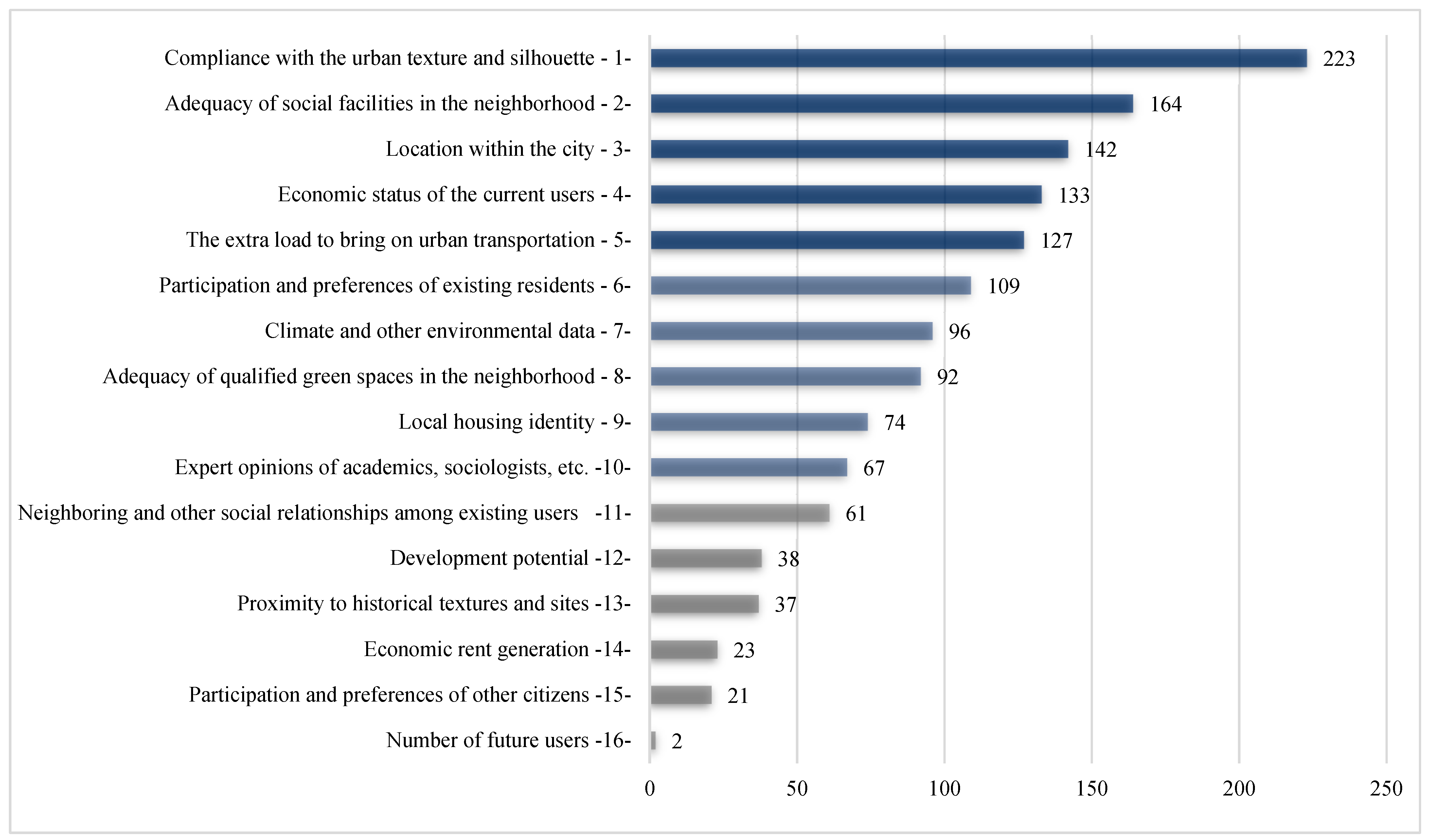

3.1.4. Strategic Approach to Determining the Scale of Housing (Physical–Social–Economic) in the Housing Redevelopment

Fourthly, the expert participants were asked to rank the criteria that should be taken into account in creating a strategic approach for determining the scale (physical–social–economic) of housing redevelopment in terms of priorities when developing (

Figure 16).

According to experts, the priority criteria for determining the scale in the housing redevelopment are as follows:

(1) Conformity to urban texture and silhouette: In this study conducted on the scale of Bursa, it can be argued that Bursa’s prior urban transformation experiences (for example, Doğanbey TOKI) have had quite an impact in prioritizing this criterion (

Figure 17A). The users of Hürriyet Neighborhood do not want to live in a higher-rise residential building (15–20 floors) (83%); they want to live in a low-rise residential building with a garden (89%) (see

Figure 6). The percentage of those who think that the low-rise buildings (3–4 floors) are effective in forming the local characteristics of the neighborhood (74%) is remarkable. It is believed that the production of high-rise residential buildings in the housing redevelopment will negatively affect local characteristics (83%) (see

Figure 9).

(2) Adequacy of social equipment areas in the neighborhood: Residents of the Hürriyet Neighborhood think that access to social facilities (i.e., education, health, shopping, mosque, etc.) within walking distance is effective in forming the local characteristics of the neighborhood (86%). On the other hand, the lack of health and education institutions and similar social facilities in the neighborhoods causes social inequality. It forces those who want to access these services from other places to bring additional traffic load to the city.

(3) Location in the city: It is thought that the location will be decisive regarding its effect on the silhouette and the extra density it will bring to the environment. It is thought that the location of the Hürriyet Neighborhood within the city is advantageous (84%) (see

Figure 7). Additionally, the users express that they are satisfied with the location of the housing they live in (83%) (see

Figure 6).

(4) Economic status of the current user: In determining the scale of housing, it is necessary to perform an in-depth analysis of the economic conditions, living standards, and social status of the user. Hürriyet Neighborhood users are generally lower-middle income earners. Even if they move out of the house they live in, they express that they want to live in the same neighborhood again (55%) (see

Figure 7) and that they do not want to live in higher houses (83%) (see

Figure 6).

(5) The extra load it will bring on urban transportation: The percentage of users (77%) who say that there is a high vehicle density and a shortage of parking spots in the Hürriyet Neighborhood is high. In the current situation, increasing the population and traffic density in regions where the density is already high is undesirable. In this case, alternative means of transportation should be provided, or a model that encourages the reduction of density should be proposed.

(6) Participation and preferences of existing housing users: If housing is to be redeveloped, the number of users who want to participate in the process and present their ideas is relatively high (82%) (see

Figure 6). Effective participation of users in all decision making and design processes provides transparency; increases trust, satisfaction, and a sense of belonging; and facilitates the achievement of accurate results. By participating in the determination of the scale, typological diversity can be created according to the preferences of the users, and monotypization/homogeneity can be prevented by creating mobility in accordance with the silhouette.

(7) Climate and other environmental data: It is necessary to evaluate essential issues such as maintaining natural air flows in the city, circulation of clean and dirty air, formation of wind and rain, and temperature increase in collaboration with experts. The fact that there are more users (77%) in the Hürriyet Neighborhood who say that their housing units receive enough sunlight is associated with the fact that the houses have few floors. However, the number of those who think their residential unit is too close to other residences (70%) is also high. The reason for this is the creation of facades very close to each other by renovating on a parcel basis (

Figure 18A–C).

(8) Adequacy of qualified green spaces in the neighborhood: As the population and housing density increase, the ratio of qualified green spaces per capita decreases. However, in the areas where housing redevelopment is carried out, there is also the destruction of the natural environment along with the existing building environment. When we look at the city of Bursa, which used to be called “Green Bursa”, with a satellite image, it can be argued that qualified green areas are particularly rare, except for large urban parks, and that they do not meet the need on the neighborhood scale (see

Figure 3).

(9) Local housing identity: Users in the Hürriyet Neighborhood think that the neighborhood has unique and local characteristics (60%) (see

Figure 7). The notable characteristics of housing in Hürriyet Neighborhood are described as follows: low-rise buildings; living with relatives and shared use of common areas; widespread use of open and semi-open interfaces such as gardens, courtyards, terraces, balconies, and doorsteps; and widespread cultivation of plants such as vines and flowers and provision of space for them within the housing. Cultural habits such as winter food preparation and the need for storage and preparation space are among the common features. The term “local housing identity” refers to the production of spaces that will ensure the continuity of unique features that are formed by the use and preferences of local users and that differentiate the area from other locations. In rapidly changing and immigration-heavy cities, it is necessary to aim for the redevelopment of housing by combining the continuity of the sense of place and belonging in these old neighborhoods, which are few in number, and the unique local features and current conditions of the local housing.

(10) Expert opinions by academics and sociologists: In the study, in-depth interviews conducted with experts have focused on the example of the Doğanbey TOKİ urban transformation project in Bursa. It has been pointed out that the results would have been different if the expert opinions had been taken into account in the process. Expert opinions should be included in the housing redevelopment process.