Abstract

The rapid development of the ever-changing information and communication society demands skills from its members that allow access to and adapt to the various situations that they may face. To achieve this, it is essential to acquire a set of key competencies throughout different stages of life, among which we find digital competence. This systematic review aims to analyse, through a series of focal points and indicators, the internationally published interventions in the last ten years aimed at improving digital literacy and the acquisition of this competence by students in early childhood education, primary education, and higher education, as well as professionals from various fields. The procedure followed for the selection of the interventions has been documented and graphically represented according to the PRISMA statement, with searches conducted across various databases and journals. In total, 26 studies were selected, covering the period before, during, and after the COVID-19 health lockdown, and the influence of the lockdown on the development of digital competence was examined. The obtained results show the evolution of the selected interventions in terms of general aspects, instructional and evaluative procedures, fidelity, and encountered limitations. The results demonstrate a growing concern for the development of digital competence, amplified by the needs arising during the COVID-19 lockdown and evidenced by an increase in interventions aimed at this goal. It also showcases the relationship between adequate acquisition and the nurturing of other psychoeducational variables like motivation or satisfaction.

1. Introduction

1.1. Digital Competence

There are multiple reasons to investigate the impact of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) on society in general. In the last decades of the 20th century, these technologies have gradually been introduced into various social areas, providing new opportunities for accessing knowledge and communication [1]. Furthermore, numerous benefits resulting from their acquisition and development have been confirmed, such as the promotion of autonomy, efficiency, responsibility, flexibility, critical, and reflective thinking, among other aspects. These elements favour the development, learning, well-being, and quality of life of this group, preparing them for their future professional life [2]. In summary, ICTs contribute to the development of society.

Currently, digital competence is considered fundamental in the school curriculum, as reflected in the Common Framework for Digital Teaching Competence. This framework is based on international proposals from organizations such as the International Society for Technology in Education [3] and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [4]. Digital competence is among the seven Key Competences that must be developed in a cross-cutting manner according to current regulations. Digital competence involves skills related to searching, obtaining, processing, and communicating information, as well as transforming it into knowledge. It encompasses various skills, from accessing information to transmitting it in different formats, using information and communication technologies as an essential tool for staying informed, learning, and communicating [5].

The inclusion of sustainability in digital competence involves exploring how the ethical and responsible handling of technology can positively impact sustainable development. This entails understanding how digital tools can be used to reduce environmental impact, promote social and economic inclusion, ensure equality in access to information and digital resources, and adopt approaches that benefit future generations. Integrating sustainability into digital competence requires a comprehensive perspective that considers both the technical and ethical and social aspects of technology utilization [6].

In this article, a systematic review will be conducted on the acquisition and development of digital competences through various interventions, as well as their relationship with psychological and educational variables, in students from different educational stages, as well as in education professionals and various occupational fields, across the entire lifespan.

The studies presented describe interventions conducted in the last ten years with the aim of analysing the development of digital competence in various contexts. This period has been selected due to the significant increase in interventions aimed at acquiring digital competence and the clear trend towards online instruction and assessment, which was accentuated during and after the COVID-19 lockdown [7]. In this systematic review, an analysis of various indicators will be carried out for each of the selected interventions. They all share several common elements: (i) pre- and post-assessment of digital competence or literacy, as well as, in some cases, the psychological and educational variables associated with them; (ii) a description, to varying degrees, of the chosen sample and the instructional procedure followed, whether online (MOOC) or in-person; and (iii), the presentation and analysis of the obtained results, concluding with a discussion, conclusion, and, in most cases, limitations and future research directions.

Finally, during the procedure, each of the articles was reviewed with the purpose of classifying them according to a set of focal points which are described below. For greater ease, they have been organized into various tables according to the following points: (i) a general analysis of the participants, the construct to be addressed, and the instructional procedure carried out; (ii) the degree of focus on the role of the instructor and the student, the materials, and the grouping chosen for the intervention; (iii) the articles have also been classified according to the evaluation procedure, constructs to be assessed, moments, materials and instruments, satisfaction, and their validation; (iv) the fidelity of the treatment was also analysed, considering controls and indicators and how they were used; and (v), the various limitations that each of the interventions may present have been observed.

1.2. Justification

An analysis of the scientific literature on digital competence development models reveals that research has primarily focused on digital literacy in educational settings, either through direct student instruction or through teacher training, with the aim of transferring this competence to students [8]. Numerous studies have addressed digital competence in relation to the social environment. Systematic reviews have been conducted on various variables from the 2018 PISA Report, such as the use of digital devices at home and social relationships [9], but not enough attention has been given to the development of online or in-person interventions specifically aimed at promoting digital competence.

The COVID-19 lockdown has underscored the growing need to develop digital literacy at all levels, both in the educational and professional, as well as in the social sphere. In this regard, there is evidence linking digital competence with psycho-educational variables [10]. Variables such as motivation, satisfaction, stress, or academic performance, coupled with distance education, resulting from the lack of resources or limited acquisition of digital competence, hinder proper functioning in the technological environment [11,12].

The results of these studies, in addition to highlighting the existing digital divides in different contexts, both in terms of internet access and digital devices [13], underscore the immediate and effective need for intervention in the methodologies used to acquire digital competence, both for students and teachers.

In response to the identified needs in the educational, professional, and social realms, interventions for digital literacy among students, teachers, and even beyond the educational field have been proposed in the last decade. Some of these proposals are in the pilot stage [14,15], while other interventions have been implemented and are the subject of our review. The studies analysed include various instructional approaches, from in-person classes to online courses, such as the well-known MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) or NOOCs (Nano and Open Online Courses), as well as blended learning, where instruction or assessment is carried out online or in person, respectively. In recent years, the number of MOOCs has increased significantly, leading to systematic reviews that analyse studies where the instructional procedure for digital competence development has been based on an online course [16,17].

1.3. Digital Competence and Sustainability

There is no universally agreed-upon definition of the term “sustainability”, especially given its consideration in various contexts. According to Kuhlman & Farrington [18], it can be defined as the maintenance of well-being over an extended, possibly indefinite, period. Additionally, research suggests that sustainability comprises three components: (i) environmental, (ii) economic, and (iii) social [19].

The examination of digital competence plays a fundamental role in promoting sustainability by enabling a comprehensive assessment of the ability of educational institutions and other organizations to adopt digital technologies effectively and ethically [20].

The development of digital competence in the educational context during the COVID-19 lockdown is closely linked to sustainability in various ways. Firstly, the rapid adoption of online education and the strengthening of digital skills among teachers and students have reduced the need for commuting, thus contributing to a reduction in carbon footprint by decreasing mobility. Additionally, online education can be more resource-efficient by reducing the need for printed materials and providing access to sustainable digital resources [21].

Furthermore, digital competence fosters a mindset more oriented towards sustainability by enabling individuals to access information about environmental and social issues, which can inspire greater commitment and action in preserving the environment and promoting sustainable practices in daily life. Increased motivation for its use has amplified concerns and the search for answers, solutions, and alternatives to current socio-environmental problems.

Collectively, digital competence plays a fundamental role in the transition toward a more sustainable world by driving efficiency, awareness, and action concerning environmental and social challenges [22,23].

This work places the social component at the forefront by addressing the global sustainable development goals, “ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education and promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all”, with a focus on digital transformation [24]. It seems natural that the integration of digital tools into educational methods would lead to an improvement in the quality of education [25,26], making it a suitable step towards achieving the aforementioned goal.

1.4. The Present Study

Therefore, digital competence is considered crucial for autonomously navigating the educational and professional challenges we face in a constantly changing society of communication and information. In the past decade, systematic reviews have been conducted that have analysed areas related to digital competence and literacy, clarifying both concepts and investigating their correct usage [27]. Additionally, there are empirical studies, bibliographical analyses, mappings, and meta-analyses of previous systematic reviews where articles related to digital competence in the educational context over the past decade can be extracted [28,29,30,31]. These analyses are descriptive, comparative, evolutionary, or clinical in nature. This review focuses on articles extracted from these studies, but specifically analyses those that include an intervention.

On one hand, there is evidence of numerous systematic reviews focused on the analysis of studies related to the acquisition of digital teaching competence. These reviews encompass various educational models centred on the development of teacher digital literacy [32] or the theoretical underpinnings of teaching competence [33,34]. They also span different educational stages, such as higher education [35] and primary education [36,37]. Although most of these reviews aim to analyse studies focused on assessing the educational practices or methodologies proposed for the development of digital competence [38,39,40,41].

On the other hand, there are systematic reviews focused on the analysis of studies investigating the evaluation of digital competence acquisition procedures in higher education students [42,43,44], in primary education [45], or in early childhood education [46,47]. Finally, due to the demands arising from the COVID-19 lockdown, the systematic review conducted by Armas-Alba et al. [48] stands out, focusing on the use of ICTS and the development of digital teaching competence in response to the educational needs of students with special educational needs during the health crisis. Similarly, the systematic analysis carried out by Scagliusi [49] focuses on the development of digital literacy for youth entrepreneurship post-lockdown.

In both cases, involving students and teachers, these are articles that assess digital competence, the teaching and learning procedures in educational structures, but without delving into interventions [50]. On the other hand, studies were found that demonstrate the development achieved in digital literacy through various interventions on teachers [51] or students at various educational stages [52,53,54,55]. There are also reviews focused on the student’s engagement, from a behavioural, emotional, and cognitive perspective, experienced when advancing in the acquisition of digital competence [56].

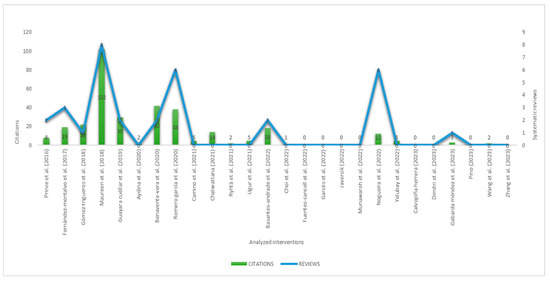

Regarding the selected interventions for analysis (see Figure 1), it is evident that some of them have been included in previous systematic reviews. For example, the study conducted by Basantes-Andrade et al. [57] was selected in the reviews by Basantes-Andrade et al. [58] and by De la Cruz-Campos et al. [59]. Similarly, the intervention conducted by Benavente-Vera et al. [60] was analysed in the study by Chavarry [61] and by Sanchez & Fernández [62]. In all four cited reviews, the analysis revolves around interventions aimed at developing teaching digital competencies. The same is true for the interventions carried out by Gómez-Trigueros & Moreno-Vera [63], cited in the review conducted by Velandia-Rodriguez et al. [64], and that of Guayara-Cuéllar et al. [65], included in the studies by Hernández et al. [66] and by Viñoles-Consentino et al. [55].

Figure 1.

Relationship between citing articles and systematic reviews that include the analysed interventions). Prince et al. (2016) [67]; Fernández-montalvo et al. (2017) [68]; Gómez-trigueros et al. (2018) [63]; Maureen et al. (2018) [69]; Guayara cuéllar et al. (2019) [65]; Aydina et al. (2020) [70]; Benavente-vera et al. (2020) [60]; Romero garcía et al. (2020) [71]; Camino et al. (2021) [72]; Chatwattana (2021) [73]; Ryhtä et al. (2021) [74]; Ugur et al. (2021) [75]; Basantes-andrade et al. (2022) [57]; Choi et al. (2022) [76]; Fuentes-cancell et al. (2022) [77]; Garcés et al. (2022) [78]; Javorcik (2022) [79]; Munawaroh et al. (2022) [80]; Nogueira et al. (2022) [81]; Yelubay et al. (2022) [82]; Calvopiña herrera (2023) [83]; Dimitri et al. (2023) [84]; Gabarda méndez et al. (2023) [85]; Pino (2023) [86]; Wang et al. (2023) [87]; Zhang et al. (2023) [88].

On the other hand, the intervention conducted by Fernández-montalvo [68] has been analysed in various systematic reviews [45,89,90] that compile studies focused on the evaluation and development of digital literacy in primary education. Similarly, the intervention published by Maureen et al. [69] is included in numerous reviews that focus on the development of literacy and digital competence acquisition in early childhood education or preschool stages [91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98].

Finally, the intervention conducted by Gabarda-Méndez et al. [85] is included in the systematic review published by Marrero-Sánchez & Vergara-Romero [99], which focuses on the analysis of interventions to improve digital competence in university students. All the reviews mentioned so far focus their analysis on digital competencies in one period or stage, highlighting the need to expand the field of study and compare it with other educational phases, an objective proposed in this review.

The article published by Romero-García et al. [71] was analysed in various systematic reviews, focusing on both teacher digital competence [64,100] and digital literacy at the university level [101,102]. It was also included in the review conducted by Reyes-Argüelles et al. [103], where 15 articles detailing problem-based learning during the lockdown were analysed. In contrast to this last review, the present one extends the scope of analysis from the period before to the one after the health crisis, including the during.

Regarding the intervention by Prince et al. [67], it can be found analysed in systematic reviews focused on the study of the development of 21st-century educational competencies and skills, uncovering articles from the last decade focused on digital competence as well as other competencies such as mathematical or literary [104,105]. The main difference with the present review lies in the specificity and depth given to digital literacy and competence, and the influence COVID-19 has had on it.

Finally, there are numerous researchers that include the article published by Nogueira et al. [81] in their reviews. Some are focused on the relationship between digital literacy, the impact of new technologies, and mathematical learning [106,107,108], while others analyse the educational structure and digital development in classrooms [109,110,111]. The present review provides an innovative perspective with a focus on development influenced by the lockdown era and the analysis of various intervention quality indicators (see Table S4).

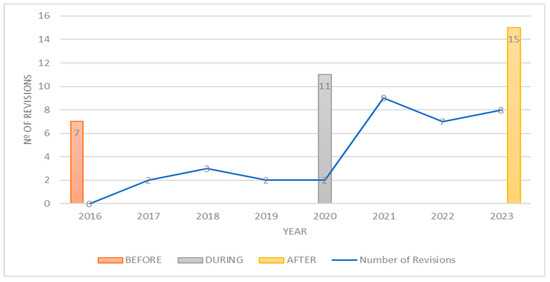

Although this review has selected the studies from these other reviews, the indicators and focuses have been different. New reviews are needed that focus, for example, on the pre-post situation and during the COVID-19 lockdown (see Figure 2). This is the first need we will address in this analysis. There is a need for a systematic review that combines the acquisition of digital competence at different stages of the life cycle with differences before, during, and after the health crisis caused by the COVID-19 lockdown, and how all of this affects psychoeducational variables such as personal satisfaction [1,112].

Figure 2.

Systematic reviews related to the acquisition of digital competence published in recent years).

This is the added value of this systematic review. In addition to all the studies related to interventions previously analysed by other authors, new ones have been selected, recently published, in order to update the scientific literature, which has been growing exponentially in recent years. Finally, the main contribution of the study is the analysis, first, by focuses and indicators and, later, of the results obtained depending on whether the intervention was carried out before, during, or after the COVID-19 lockdown.

The systematic review addresses the problem through the following research questions: (i) What are the results of empirically validated interventions related to teachers and students, their causal, mediating, and moderating roles in relation to psychological variables in the acquisition of digital competence? (ii) How does the instructional and evaluative procedure affect the development of digital literacy and psychoeducational variables in teachers and students? (iii) What are the strengths and limitations found in the various articles analysed? What can be contributed to future research lines? (iv) How does the COVID-19 lockdown affect the effectiveness of these procedures and the role of variables?

The answers to the various research questions have been obtained through the achievement of general and specific objectives. The general objective was to carry out a systematic review focused on empirically validated interventions in recent years, with national and international data. Specifically, it focused on variables related to the development of digital competence and psychoeducational variables. The specific objectives included: (i) Discuss the focuses analysed in each of the reviewed articles, detailing their instructional and evaluative procedures, the characteristics of the participants, objectives, results, conclusions, and fidelity. (ii) Identify the limitations and future research lines of each of the articles, offering alternatives and practical applications.

To achieve these objectives, the following working hypotheses were proposed: (i) Relevant differences in the contributions of empirical evidence from the studies by focuses would be observed: instructional procedure, evaluative procedure, participant characteristics, objectives, results, conclusions, and fidelity; (ii) differential psychoeducational patterns contributed by the analysed and classified interventions, the results obtained in them, and their relationship with the development of digital competence would be identified; (iii) it is expected that the evidence obtained will demonstrate the relevant mediating role of psychological variables in the causal relationship between digital literacy competencies through content and academic, learning, and adaptive outcomes; and (iv) the differences and similarities extracted after the analysis by focuses, sequenced in the pre-, during-, and post-COVID-19 lockdown stages would be evidenced.

2. Method

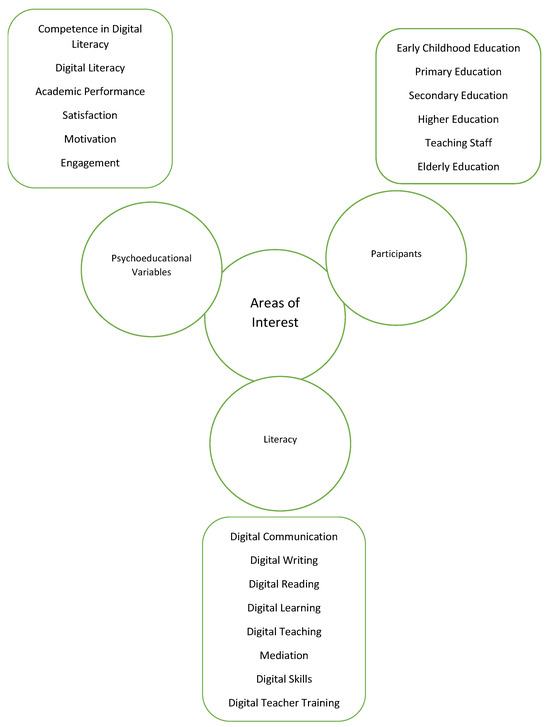

To carry out this systematic review, a four-phase procedure was followed, based on the model by Miller et al. & by Scott et al. [113,114], which are detailed as follows: (i) starting with a diagram of relevant terms and thematic axes (see Figure 3), a literature search was conducted using databases such as Web of Science, Scopus, Research Gate and in journals such as MDPI or Frontiers; (ii) the inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied with the addition of other criteria, such as studies published in peer-reviewed journals, reference databases, and citation indexes, following the contributions of Cooper et al. [115]; and (iii), once the inclusion and exclusion criteria were established, they were applied following an agreement between the observers for their coding, with the aim of conducting qualitative and quantitative analyses.

Figure 3.

Search terms used for the selection and screening of articles to analyse.

On one hand, both the subject and the content and terms were carefully selected, taking into account the educational needs related to the acquisition and development of digital competence as previously mentioned in the theoretical framework and evidenced by studies [116,117]. On the other hand, once the search terms were defined, which provide meaning to digital competence, the range of participants has been narrowed down. The selection covers the entire life cycle of an individual, including Early childhood, primary, secondary, and higher education, without forgetting the teaching staff. All of this is done with the purpose of comparing the development observed in various educational and biological stages [57,69]. Regarding the search criteria, focus areas, and selected indicators for analysis, those considered essential for conducting a comprehensive quality analysis of each intervention were chosen [113,114].

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

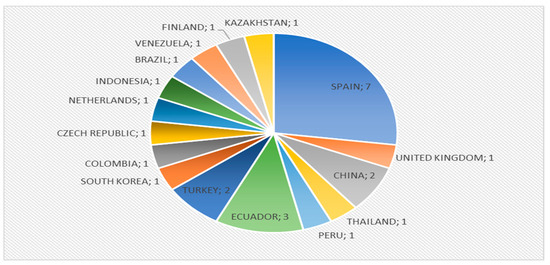

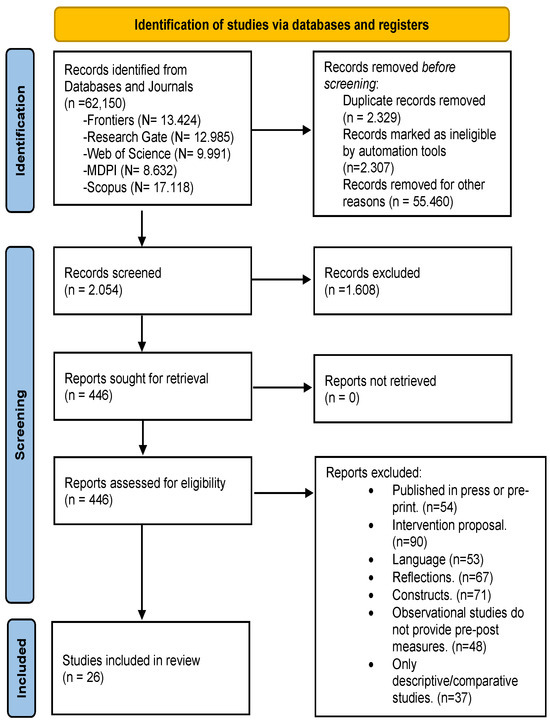

At this point, it should be noted that the procedure will be documented and graphically represented according to the PRISMA statement [118]. A total of 26 intervention studies were identified and collected through a search in databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, or Research Gate, and from journals such as Frontiers or MDPI. These studies were classified and analysed using tables that cover various aspects, including general aspects, evaluation instruments, treatment fidelity, instructional procedure, and limitations. The selected studies were sequenced based on their publication date, before, during, and after the COVID-19 lockdown. A column structure was used to describe the indicators, and rows were used for each of the selected interventions (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Number of interventions published by country among those analysed.

For the selection of articles to be analysed, a series of inclusion and exclusion criteria were taken into account. Regarding the typology of the studies, only those related to instructional interventions carried out, only studies that have been published (not in press or preprint) in the last ten years (January 2013–October 2023); the theme of the articles is related to digital competence and psychological variables. Regarding the language, we include those written in English or Spanish, regardless of where they have been implemented. Therefore, studies published in other languages are excluded.

We select those that refer to an instructional intervention that contrasts some digital competence improvement program with psychological variables, excluding single-case or clinical studies. Therefore, other types such as comparative, descriptive, evolutionary, interpretative, and proposals were excluded. Intervention studies that do not contain analyses of psychological variables as well as observational studies that do not provide pre-post intervention measures were excluded.

Hence, the resulting number of 26 studies. Nevertheless, this number of studies is considered appropriate, considering the systematic reviews conducted and published in Sustainability in recent years, focusing on the development of digital competence (see Table S5).

Regarding the assessment of study quality following the PRISMA approach, the analysis focused on treatment fidelity is considered the most crucial aspect in appraising their quality. Consequently, this analysis is also seen as an assessment of quality. A detailed exploration of the fidelity indicators for each intervention has facilitated the creation of a helpful ranking, reflected in a specific table as described in the corresponding results. This analysis, based on the rigorous control of scientifically validated interventions, provides a quality assessment approach from that perspective.

Furthermore, it delves into the limitations of the studies, allowing for a comparative analysis between them regarding their methodology and the context of their published reports. This encompasses evaluating methodological and contextual strengths such as currency, precise problem formulation, rigorous analysis of the measurement of psychological constructs and considered competencies, instrument validation, coherence between propositions and backgrounds, discussion and conclusions, and the appropriate use of data to support claims.

Overall, this approach offers an evaluation of article quality from a broader perspective, encompassing both formal and content-related aspects, beyond the specificity of the intervention, which is primarily assessed based on treatment fidelity.

PRISMA checklist has been included, as an example, for three interventions, one for each period (pre, during, and post COVID-19) [68,72,77] (see Tables S1–S3).

After defining objectives, hypotheses, and research questions, inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as keywords, were established. These were structured as search terms to build the search string.

Subsequently, the same procedure was followed in all databases and sources. Keywords were added, combined with “AND” or “OR” between each of them. In the search engine, results were filtered based on exclusion and inclusion criteria such as: publication period (2013–2023), open access, language and document type. An example of a search string would be the one used in Web of Science: TS = “digital competence” OR “digital literacy” AND “education” AND “intervention”. Timespan: 2013–2023. Open access.

3. Results

The aspects that were reviewed, ranging from more general indicators such as participants, duration, or objectives of each study, to more specific ones like quality indicators or fidelity to check the validity of each intervention. The review has concluded with a more specific examination of the instructional procedure proposed in each study and its evaluation, to understand and extract the details of each, compare them, and show their similarities and differences. After analysing these indicators, the limitations found in each of the interventions were classified to highlight the difficulties that readers may encounter when drawing conclusions due to the absence of various data (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

PRISMA flow diagram. Details of the number of studies selected and excluded at each stage along with their reasons.

3.1. Comparison among the Different Focuses

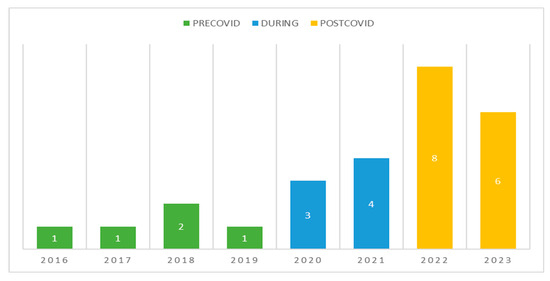

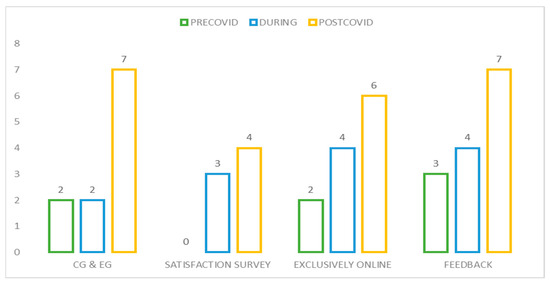

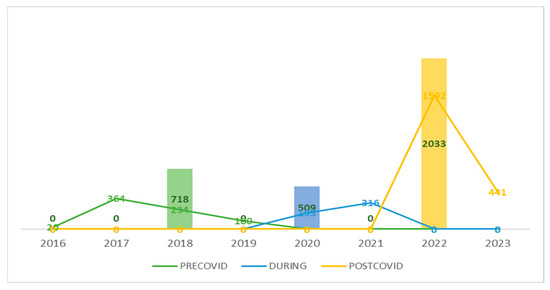

Before delving into each of the approaches and comparing them in general, significant differences can be observed in various indicators before, during, and after the COVID-19 lockdown period. The first difference concerns the number of studies focused on acquiring digital competencies, showing a clear increase in the quantity of interventions aimed at achieving this goal since the end of the lockdown (see Figure 6). This has entailed a larger participant sample as the health crisis was coming to an end, and a preference for online or blended modalities was observed, which has been predominant up to the present year, with a trend toward in-person learning again (see Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Number of selected interventions by years. Before, during, and after COVID-19.

Figure 7.

Development of the number of interventions providing information on the following’s indicators pre, during and post COVID-19.

Furthermore, a higher number of participants has enabled an improvement in the instructional and evaluative procedure, which has become more controlled, with a growing preference for the division into Control and Experimental Groups. Additionally, there was an increased focus on assessing participant satisfaction, especially since the middle of the health crisis. To achieve positive results in this indicator, continuous information exchange between instructors and participants has been encouraged (see Figure 7).

The studies selected from the period prior to the lockdown primarily focus on the acquisition of digital competence as defined by the European educational framework. There is much less concern for its professional development, as evidenced by the number of studies conducted in these years, particularly those addressing professional development rather than purely curricular development. These studies form the foundation for the design of interventions aimed at this goal and mark the beginning of the use of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs).

During the years of the health crisis, there is a growing concern for the educational and professional development of digital competence due to the needs arising from online education and remote work. This is evident in an increased number of interventions aimed at achieving digital literacy in various domains. These interventions provide guidelines for online instruction and assessment. These procedures are complemented by online monitoring, using digital resources such as virtual classrooms, rubrics, and online forms. In addition, psychoeducational aspects have become a concern for researchers, including academic performance and participant satisfaction. To address these concerns, online meetings and feedback mechanisms between instructors and participants have been introduced.

Finally, after the period of restrictions resulting from the lockdown, there is a surge in interventions aimed at promoting digital competence in all areas. It has become one of the primary goals for the proper development of society. The main contributions during this period include significantly larger sample sizes than in previous years, longer-duration instruction, and a trend toward hybrid and in-person modalities. This trend is evident in the last year, marking a shift away from online-only interventions. The assessment of psychoeducational constructs like motivation and participant well-being becomes more established, driven by academic problems encountered during the quarantine and health crisis.

3.1.1. General Overview

When analysing interventions, it is important to consider various general aspects that can influence their effectiveness. These aspects include the participants involved, the specific construct or topic addressed, the research questions, and the stated objectives. It is also relevant to consider the professional context to which the intervention is directed, as the approaches and strategies used can vary depending on the context. Another aspect to consider is the instructional procedure used, which can include specific techniques and strategies to facilitate learning and skill development.

3.1.2. Assessment Instruments

The assessment of an intervention is fundamental to understand its effectiveness and make necessary adjustments. In this regard, it is important to define the appropriate time for evaluation, either during the intervention or upon its completion. Direct observations can provide valuable information about the participants’ performance in real-life situations. Additionally, performance tasks can be used to assess the practical application of acquired knowledge. Questionnaires and self-reports, as well as rating scales, are common tools for collecting data from participants. Other assessment methods include the use of physical or virtual portfolios to collect work samples and the evaluation of intervention effects, participant satisfaction, and result validation through individual or group feedback.

3.1.3. Fidelity and Quality of the Treatment

The fidelity of an intervention refers to the extent to which it is implemented according to the established plan. To assess fidelity, the timing of the comparison between the intervention group and the control group, if applicable, must be considered. It is also important to have a written protocol detailing the steps to follow in the intervention and ensuring consistency in implementation. Comparable training for instructors is crucial to minimize variations in intervention implementation. Detailed records should be maintained to assess whether the intervention is being applied consistently and uniformly. Additionally, it is essential to evaluate the relevance of the intervention and conduct regular meetings to provide feedback and make necessary adjustments.

3.1.4. Instructional Procedure

The instructional intervention encompasses various aspects related to the design and implementation of learning activities. This includes the selection and development of appropriate teaching materials, the instructor’s role during the intervention, the participants’ role in the learning procedure, and the grouping of participants in collaborative activities. The context in which the intervention takes place must also be considered, whether it is in a formal educational setting or a specific professional environment. The duration of the intervention is also a factor to consider as it can influence the depth and quality of learning. Finally, it is essential to assess the results obtained through the intervention and analyse whether the stated objectives were achieved.

3.1.5. Limitations

Despite good intentions and efforts made in interventions, it is important to recognize and address any limitations that may arise. These limitations can manifest in various aspects, such as the available background on the study topic, the participant sample used, the measurement instruments employed, the intervention program design, the results obtained, the discussion and conclusions made, as well as general limitations that can affect the validity and generalizability of findings. Recognizing these limitations and highlighting them in the research is essential as they provide a critical and transparent view of the study. Furthermore, additional comments and reflections can help contextualize and better understand the identified limitations.

All the selected studies show interventions in which the digital competence is assessed both before and after instruction. The aim is to assess the teaching and learning procedure, whether there has been an improvement in participants’ digital literacy, and to what level this competence has been acquired. Below are five tables, each focusing on specific constructs, and a detailed explanation of each one.

3.2. General Overview

Research on digital competence and literacy has been the subject of study in various works in recent years. The analysed findings indicate the importance of understanding how the lockdown has affected research in this field and how digital competence has become even more relevant in today’s society. Some of them have limitations in terms of presenting data from the participant sample. However, other researchers have managed to provide detailed information. In terms of intervention design, a high number of them opt for a quasi-experimental, descriptive, and cross-sectional approach, contributing not only to digital competence but also to other educational areas such as linguistics or mathematics, and even to other professional fields such as healthcare or IT. The selection of a purely qualitative or quantitative analysis or a mixed one offers a greater variety of choices (see Table 1).

Table 1.

A comprehensive analysis of the reviewed empirical teaching studies, addressing elements such as the participant subjects, the groups involved, the methodological design, the examined concepts, and the skills developed. Each of these aspects is detailed in the report’s content.

In most cases, data from the participant samples have been presented, but not in studies such as those by Benavente-Vera et al.; by Chatwattana & by Garcés et al. [60,73,78] where only the total number of participants is shown, without specifying gender or average age. Regarding the COVID lockdown, a lower average number of participants was observed during the health crisis due to the difficulties encountered during the period of restrictions on gatherings. It was higher before and with a greater difference after the health crisis (see Figure 8). Within the sample, with respect to groupings, half of the studies propose intervention on a single experimental group, without dividing it with another control group. The use of a division into EG (experimental group) and CG (control group) increases after the lockdown, adding originality and higher quality to post-COVID studies because dividing the sample into two groups allows for a differential analysis of the constructs studied, thus improving the reliability of the research and the effectiveness of the instruction provided [81,88].

Figure 8.

Accumulation of selected participants in the samples each year. Pre, during, and post COVID-19.

As for the construct being worked on, all articles focus on digital competence or literacy in the same field. The studies by Yelubay et al. [82], which focus on motivation, by Maureen et al. [69] on linguistic competence, and by Romero-García et al. [71] on academic performance, stand out as exceptions, adding an extra dimension for analysis. It is important to highlight the significance of psycho-educational variables such as motivation and satisfaction during and after the quarantine period, becoming priorities to evaluate in most interventions. Due to the restrictions during the health crisis, which caused various psycho-educational issues in students and teachers, the protection, care, and development of psychological variables related to education, such as motivation, commitment, digital well-being, and academic performance, gained importance in interventions once the state of emergency was lifted [86,87].

Instruction focused on achieving the highest possible level of digital competence has influenced the selection of techniques and strategies for interventions. There is a clear trend toward designing and implementing online courses (MOOC and NANO MOOC), digital applications, websites, and virtual classrooms aimed at practical use to improve digital literacy. Virtual intervention becomes more pronounced during the years when COVID-related health measures are in place, as online education is seen as necessary. This trend continues in studies published after the lockdown, with the use of gamification [76] and social networks [70,77]. After the health crisis, there is a stagnation in the trend toward online intervention, with the number of studies opting for in-person modalities equaling those using online methods [83,86].

Regarding the instruction provided, the mentioned studies that aim to develop psycho-educational variables propose a different instructional procedure. For instance, Wang et al. [87] use gamification to foster engagement and digital well-being. Pino & in Yelubay et al. [82,86], case studies applied to solving problems relevant to participants’ lives and various tasks with playful elements, such as video editing, quiz solving, or online forum debates, are proposed to enhance student motivation, instead of a more traditional instruction. Similarly, Maureen et al. [69], focused on acquiring linguistic competence, and Romero-García et al. [71], focused on academic performance, propose instructional procedures with some original contributions, such as a classic and virtual storytelling or a customized mathematical game and workshop, respectively.

Finally, the research objectives and questions are referenced. Among the analysed articles, some explicitly include both questions and objectives, while others include one of the two indicators. The study by Benavente-Vera et al. [60] does not specify either. The indicators related to the stated objectives or questions mainly focus on verifying the effectiveness of the intervention and assessing the level of development of the worked construct, which in these studies is the acquisition of digital competence. It is observed that studies in which the development of another psycho-educational construct, such as commitment, motivation, or academic performance [71,86,87], is combined with the development of digital competence, are reflected in the research objectives or questions as a goal to achieve. This becomes more prominent during and after the lockdown when the achievement of these variables’ development is emphasized as an objective to affirm the effectiveness of the intervention.

To facilitate the identification and reading of the displayed results, the table has been condensed. As a result, some indicators are retained in this document, while the remaining ones can be found in the supplementary materials section (see Table S6).

Meaning of abbreviations in the table: NM = Number of men; NW = Number of women; EG = Experimental group; CG = Control group.

3.3. Assessment Instruments

The analysis of the evaluation instruments in a study refers to the procedure of examining and critically evaluating those used to collect data and obtain relevant information within the framework of an intervention. The assessment of digital competence and literacy has also been the subject of study where different instruments have been employed to measure participants’ progress. We will analyse the evaluation approaches used in these studies, focusing on the application of the instruments at different times and under the influence of the COVID-19 lockdown. The participants are mostly from educational environments, ranging from primary education to university students or teachers. The latter group predominates in interventions following the lockdown, with the aim of training future teachers to use digital tools efficiently (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Evaluation tools used in the educational implementation of the analysed studies are described in detail in the report, presenting a comprehensive comparison among the various instruments and their application.

In addition, we will highlight the moments when each of the evaluation instruments is applied. All the studies conduct a diagnostic and final evaluation after the intervention. The article by Munawaroh et al. [80] stands out as it includes an evaluation conducted weeks after the final assessment to check if the results persist over time. Regarding the influence of COVID, the health crisis has compelled not only the instruction but also the evaluation procedures to be conducted online. This necessity has adapted the assessments of successive studies, maintaining digital tools in assessing the progress made in most articles [79,88].

Not only have evaluations been conducted before and after the instruction, but some interventions also include ongoing monitoring using various resources. On one hand, regarding the portfolio used, the use of questionnaires or surveys in diagnostic, formative, and summative evaluation stands out. On the other hand, rubrics are used for completing activities, and in the study by Prince et al. [67], interviews with participants are utilized. Once again, there is a progression towards digitizing various evaluative instruments, evolving from paper questionnaires or surveys to the use of online forms like Google Forms. Reliability testing of these instruments with proprietary data is also observed in most studies, with some exceptions [63,65,78].

The observations are also described, where there is a general focus on performance, difficulties, and limitations. In some studies, such as Wang et al. [87], psychoeducational variables such as engagement, motivation, or interest are observed and evaluated. In the studies by Yelubay et al. & by Pino [82,86] variables such as digital well-being and motivation are assessed through questionnaires and case studies. Concerns have arisen from the quarantine and the sudden introduction of online education in the educational context, affecting both teachers, students, and their families.

The last group includes various studies that introduce satisfaction surveys for the participants’ families, adding extra value to the intervention. There is a growing concern about the satisfaction of participants and their families due to the digital tools introduced during the health crisis [71,73,75]. This evaluation continues after the lockdown, being absent before it. Once the instructional and evaluation procedure is completed, a questionnaire is sent to assess the satisfaction with the course. The results obtained in these types of surveys reinforce the need to use MOOC-type interventions to develop digital competence, as the satisfaction of participants and their families is high [57,83].

Finally, reference is made to both task performance evaluation and what is assessed with the evaluation instrument, with recurring results in the vast majority of interventions. In the first group, the focus is on competence level, performance, mastery, and the results of the pre- and post-tests. In the second group, the instruments are used to assess the design and effectiveness of the course conducted, as well as digital competence, either in a generalized manner or divided into areas or subfactors [57,76,77]. In conclusion, the last column provides critical comments on the evaluation procedure of each article.

To facilitate the identification and reading of the displayed results, the table has been condensed. As a result, some indicators are retained in this document, while the remaining ones can be found in the supplementary materials section (see Table S7).

3.4. Fidelity and Quality of the Treatment

Regarding the quality control of interventions, different treatment fidelity indicators can provide valuable information to understand the rigor, confidence, and potential for generalization of results to other studies or educational practices, enabling them to be considered empirically validated studies or interventions. To achieve this, they are classified according to a series of indicators outlined below (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment fidelity refers to the consistency of implementing the educational approach. The report provides a comprehensive description of each control element and indicator, detailing their comparative application across the various studies. Additionally, it includes the measurement factors and adjustment variables used in the pedagogical intervention in the analysed studies.

Initially, it can be observed that all interventions share a common pattern. They begin with a prior empirical review before designing the course, followed by a needs analysis or diagnostic assessment of the sample population for which the intervention is intended. This is done to design an optimal and efficient intervention capable of adapting information found in previous articles to the selected participants. To enhance the course’s instruction, in addition to the prior reviews and needs assessment, meetings with experts [67,74,81] or instructor training [70,76] are conducted. Subsequently, the instruction and ongoing and final evaluation take place.

Next, the instructional procedure is detailed, with a common factor in all interventions being the execution of online activities during the course to improve digital literacy. This includes the use of storytelling [69], gamification [87], and case study resolution [86], which contribute originality to the procedure. The entire procedure is monitored and observed, mostly online, except in the case of Guayara-Cuéllar et al. [65], where it is not specified. This monitoring can begin to lean towards online methods, such as virtual classrooms, particularly during the COVID-induced quarantine, and continues even after its conclusion. Among the remaining indicators, it is worth highlighting the predominant use of continuous online portfolios, which include tasks, activities, problem-solving, case studies, forums, debates, and games.

Continuing the analysis, it is indicated whether the program script is detailed in a broken down or schematic manner [60,78,79,81]. Regarding the relevance of the instruction, the majority of interventions are curriculum-based, with horizontal alignment seen in only a few articles [76,83,87]. It is noteworthy that in some studies, both vertical and horizontal approaches are combined, especially during and after the health crisis [73,77,82,86].

The instruction is applied equally to all participants, except in studies comparing an experimental group and a control group, where the experimental group receives the instruction while the control group does not. The use of two groups was observed occasionally before the COVID-19 lockdown [68,69], and it became more common during [71,73] and after the lockdown [76,80,88]. The division into control and experimental groups adds value to the studies by providing another comparison between participants, enhancing result consistency.

Finally, concerning the feedback provided by instructors, more than half consistently inform participants. A higher concentration of studies considering communication with participants as essential is observed in interventions conducted after the lockdown, a period, during which constant contact between instructors and students through ICTs became normalized [57,77,81,82,83,85,87]. There is a clear trend toward constant online feedback, both with participants and their families [81]. Regarding communication among stakeholders during instruction, the use of meetings is evident. Meetings are used in half of the interventions analysed, both before and during the health crisis, and are present in the majority of interventions proposed after the crisis.

To facilitate the identification and reading of the displayed results, the table has been condensed. As a result, some indicators are retained in this document, while the remaining ones can be found in the supplementary materials section (see Table S8).

3.5. Instructional Procedure

The analysis of the instructional procedure is a fundamental phase in the design and development of education and training, particularly in the context of teaching and learning. It refers to the systematic and detailed study of all the stages involved in creating an intervention. In this phase, a comprehensive evaluation of the educational context and the students to whom the instruction is directed is carried out. The main aspects addressed during the analysis of the instructional procedure are outlined below (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Instructional procedure. Parameters and monitoring measures implemented throughout the various interventions. The report provides a detailed analysis of each of the control elements and indicators and describes how they were comparatively applied in the different studies.

Initially, the roles of both the instructor and the student are highlighted. It is observed that the instructor performs the roles of a researcher and instructor, while the student actively participates in each activity. Furthermore, an equitable distribution is noted in terms of grouping into large or small groups and the context of application, whether online or in-person, except for those published during the lockdown, where online mode predominates. Before and after the lockdown, it is noted that there is a similar number of interventions that choose one or the other criterion, although some articles opt for a combination of both modes, both in-person and online [60,71,76,85].

The results of the interventions expose the contrast between the initial assessment of the participants conducted before the instruction with those derived from the questionnaires and tests completed once the course is finished. In all of them, significant progress is shown in terms of digital competence acquisition, with more evident results in studies that present a comparison between EG and CG, where the experimental group has achieved greater development in digital literacy. Depending on the article, the results are shown more explicitly, through tables and graphs, categorizing them based on the treatments applied [60], the areas worked on [71], or the different psycho-educational variables [87].

Regarding the effectiveness of online or in-person instruction and monitoring, considering the results of each study, which base the intervention’s effectiveness on the comparison of pre and post results and, where applicable, the CG and EG, we can affirm that both modalities produce positive effects on the participants. In both situations, technology tools are used, as practical tasks are performed on digital devices, with the difference being the physical presence in the instructor’s classroom or through a virtual classroom, or the method used for evaluation or the classes delivered. In all cases, the use of ICTs is essential.

The selection of an online modality versus an in-person one is based on the initial digital competence level of the participants or, in studies conducted during the lockdown, the emerging needs of that period. Therefore, it is evident that both online and in-person modalities are equally effective in acquiring and developing digital competence, and their selection has not been made to ensure the intervention’s effectiveness, but based on the needs of the moment, available resources, or the characteristics of the chosen sample.

The analysis of the instructional procedure is completed with the presentation of the duration of the instruction in each study. A wide range is observed, divided into modules or courses, starting from four sessions [60] to the entire school year [85]. Articles published during the lockdown show a shorter duration than those before and after it, with the latter suggesting more long-lasting instructions. Regarding the materials used, as it concerns the training of digital competence, there is a clear trend toward the use of ICT, social media, virtual classrooms, Google, and MOOC-NANO MOOC.

3.6. Limitations

The analysis of limitations in studies refers to the procedure of identifying, evaluating, and discussing the constraints or weaknesses that affect the validity, reliability, or generalizability of the results obtained in each intervention. This phase is essential in presenting the findings as it provides a critical and transparent assessment of the scope and implications of the results, enabling a more precise interpretation and a proper understanding of the quality of the research conducted (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Limitations of the educational strategies addressed in the examined empirical studies. Each of these areas is detailed extensively in the main report.

In analysing different the interventions of various studies, several limitations have been identified in each of them. These interventions have been classified according to the specific indicators detailed in the corresponding columns and comments have been added for each selected study. Therefore, in this section, a comprehensive analysis of these limitations will not be provided.

In general terms, a common limitation observed is the failure to explicitly present the objectives, research questions, or hypotheses raised. As a result, the conclusions do not address the questions, nor do they indicate whether the objectives were achieved or if the hypotheses were fulfilled. Another limitation that has been found recurrently is the uniform application of treatment to the entire sample group, without making a distinction between an experimental group and a control group.

Additionally, in selecting the sample, there was limited information about the characteristics of the group, such as gender, age, inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as the randomness in the sampling procedure. When choosing the sample, once again, there was limited information regarding the group’s characteristics, gender, age, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the randomness of the sampling procedure in a generalized manner.

To facilitate the identification and reading of the displayed results, the table has been condensed. As a result, some indicators are retained in this document, while the remaining ones can be found in the supplementary materials section (see Table S9).

4. Discussion

In this discussion, we will analyse the results obtained in the study based on the stated objectives, provide an evaluation of the response to the research questions, explore practical applications of the work conducted, identify encountered limitations, and present possible solutions for future research.

In comparison to other systematic reviews published in recent years, focused on the analysis of one of the two groups involved in the teaching–learning procedures, the teaching staff, we can observe, on one hand, systematic reviews focused on the theoretical foundation and models applied by educators [32,33,34]. On the other hand, there are evaluations of practices and educational methodologies proposed for the development of digital competence [38,39,40]. This article provides a novel approach by analysing interventions specifically designed for the acquisition and development of teacher digital competence, using results obtained from the analysis of the models, theoretical foundation, practices, and methodologies selected in the mentioned reviews.

Given the division observed across different educational stages, both for educators in higher education [35] and primary education [36,37], as well as for students in higher education [42,43,44], primary education [45], or early childhood education [46,47], where articles assess digital competence and teaching–learning procedures within educational structures, yet without delving into interventions [48,49,50]. This review has amalgamated the various educational stages into a single analysis, with the aim of conducting a more comprehensive analysis, focused on the individual’s life cycle. Consequently, there has been an in-depth exploration of the digital literacy development field, not only concerning the range of stages and years of research but also in terms of adherence to the analysis of interventions aimed at competency development.

This study adds value by not only analysing the instructional and evaluative procedures, limitations, general aspects, and fidelity in interventions directed towards the acquisition of digital competence [53] but also by linking these to psychoeducational constructs [56]. This includes interventions performed on educators [51] or students from various educational stages [52,54,55]. It highlights the evolution observed in the research field during the pre-lockdown, lockdown, and post-lockdown COVID-19 periods. The results obtained have been related to indicators and focuses based on the needs emerging from the health crisis, giving rise to new evidence and trends in the research field. The significance contributed by research and empirical analysis to the acquisition of digital competence in recent years is evident in this systematic review.

The objectives set at the beginning of the research have been evaluated based on the results obtained. Each of the objectives has been systematically addressed, allowing for progress and the achievement of expected results. This has enabled the completion of a systematic review of interventions carried out in the last decade, discussing the analysed focal points, their indicators, and the changes experienced during the health crisis. All of this has revealed limitations and future lines of research, paving the way for practical applications detailed further on. Furthermore, the proposed hypotheses have been largely confirmed, thereby substantiating the validity of the approach and methodology used.

The research questions of the study have been answered satisfactorily. The collected data and the analysis performed have provided strong evidence to address each of the research questions, leading to a deeper understanding. (i) What are the results of empirically validated interventions related to teachers and students, their causal, mediating, and moderating roles in relation to psychological variables in the acquisition of digital competence? The results analysed in the corresponding section have shed light on the roles of both students and teachers within each of the interventions. They have also highlighted the relationship of their roles with psychological variables such as satisfaction or motivation, which have proven to be crucial in acquiring digital competence. (ii) How does the instructional and evaluative procedure affect the development of digital literacy and psychoeducational variables in teachers and students? Again, in the tables where each intervention has been analysed, the relationship and importance of an instructional and evaluative process that considers the motivation of both students and teachers, as well as their well-being or satisfaction, are shown. (iii) What are the strengths and limitations found in the various articles analysed? What can be contributed to future research lines? When analysing the different interventions, various limitations have been successfully identified in each of them, allowing for an answer to this question, all categorized in the corresponding table. On the other hand, a future line of research is established, which would be conducting a meta-analysis. Alternatively, as a practical implication, an improvement in educational methodologies is suggested, favouring not only learning but also the development of key psychoeducational variables in the acquisition of digital competence. (iv) How does the COVID-19 lockdown affect the effectiveness of these procedures and the role of variables? The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic-induced lockdown has been evidenced not only in the acquisition of digital competence but also in the increasing relevance and importance attributed to various psychoeducational variables related to it.

Furthermore, within the analysis of the results, the importance of the instructional and evaluative procedures in digital literacy development has been emphasized, along with the changes experienced during the lockdown and how these affect the analysed indicators. All of the above has allowed for the identification of both limitations and strengths in each of the selected studies and, consequently, their potential contributions to future lines of research and practical applications.

As an added value of the present work, a triple analysis of the quality of the reviewed studies is presented. Initially, it is assessed within the inclusion and exclusion criteria, excluding articles lacking comparative data in proposals, reflections, or interventions. Subsequently, within the “Results” section, a specific focus on evaluating quality and fidelity of treatments is included, featuring a corresponding table and its description. Finally, it culminates with an analysis centred on the limitations, providing this systematic review with both a comprehensive and specific assessment of the Quality of the selected interventions.

On the other hand, when examining the results obtained, the development of digital competence in education and various institutions during the lockdown contributes to sustainability by reducing the ecological footprint and promoting greater awareness and action on sustainable issues. The analysis of this skill set enables the identification of areas in need of improvement, fosters innovation, and eases the transition towards more sustainable psychoeducational models. This is achieved by taking into account environmental, social, and economic factors in the implementation of technological solutions, ultimately contributing to the preservation of resources and long-term well-being.

Despite the significant results, some limitations in the research were identified. One of the main challenges was the selection of the languages in which the articles have been published, as those translated into English and Spanish were chosen, which could significantly reduce the number of selected articles. To address this limitation in future studies, we suggest broadening the range of included languages, thereby increasing the sample of interventions.

Due to the rapid developments in technology and digitalization in recent years, coupled with the impact of COVID-19 on digital competence, and the difficulty of finding interventions in this field dating back before 2016, the selected range has been a decade. It would be advisable to analyse the numerous interventions that are expected to be published in this field in the near future in future research.

One of the main limitations encountered was attempting to classify the analysed interventions into the three periods based on their publication date rather than their implementation date. This was due to a lack of detailed information in some studies regarding when exactly the interventions took place. In these cases, the publication date becomes the only available and reliable information to organize the articles, providing methodological consistency to the systematic review.

On the other hand, organizing the studies based on the publication date could ensure a more consistent comparison over time. This would allow evaluating how interventions have evolved as the literature progresses, facilitating the identification of trends and changes in strategies over the years.

The publication date reflects the context in which the study was conducted and its relevance at that time. This is crucial for understanding the specific conditions, approaches, and concerns during the pre, during, and post-COVID periods.

The need for future reviews that classify interventions based on their implementation year is acknowledged, as there might be a difference of several years between that date and the article’s publication.

The findings of this study have various practical applications in the relevant field. On one hand, the obtained results enable educators to identify successful approaches, facilitating the adjustment of educational strategies to suit diverse contexts. Furthermore, it can influence educational policy formulation by providing key insights into enhancing the acquisition of digital competence in various circumstances. Simultaneously, by acknowledging the relationship between digital competence and psychoeducational variables, specific tactics can be developed for a healthy and constructive use of technology.

Also, in this systematic review, only articles that presented interventions were selected, leaving aside pilot proposals, which are mentioned in the introduction. It is recommended to conduct a systematic review that analyses different pilot proposals with the aim of implementing them in the future. Finally, as an idea for a future line of research could consider a systematic review in the form of a meta-analysis. This would combine results obtained from qualitative and quantitative analyses, significantly enhancing the study’s quality.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review has successfully analysed interventions aimed at acquiring digital competence before, during, and after the COVID-19 lockdown. Through five tables, a range of focal points has been classified and discussed, encompassing general aspects, instructional procedures, evaluation instruments, fidelity, quality, and limitations. Each of these focal points was associated with various indicators, which facilitated the analysis of the results. These findings have highlighted the increasing significance of digital literacy in recent years, as well as various psychoeducational variables associated with this construct, such as motivation and satisfaction. All of this takes on particular relevance in light of the needs arising during the health crisis.

The recommendations stemming from this study are aimed at enhancing the sustainability of the development of digital competence in educational and familial contexts, as improper use and implementation of new technologies can pose a threat to sustainability.

The social significance of this work lies in the potential for the proactive development of pedagogical recommendations that are perceived as valuable in improving the sustainability of education in relation to the use of digital tools, taking into account both the educational and family contexts.

In conclusion, while this review has effectively met its objectives, provided answers to research questions, and contributed valuable and original insights to the field of educational research, it has also revealed certain limitations. Instead of viewing these limitations as failures, they should be considered as the foundation for future lines of research and practical applications, which will further contribute to the growth and sharing of knowledge.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su16010051/s1, Table S1: PRISMA checklist Camino et al. (2021); Table S2: PRISMA checklist Fernández Montalvo et al. (2017); Table S3: PRISMA checklist Fuentes-Cancell et al. (2022); Table S4: Distribution of the analysed interventions included in other previous systematic reviews; Table S5: Systematic reviews related to digital competence found on the Sustainability website, including the years covered, number of studies analysed, and the added value our study brings to them; Table S6: A comprehensive analysis of the reviewed empirical teaching studies, addressing elements such as the participant subjects, the groups involved, the methodological design, the examined concepts, and the skills developed. Each of these aspects is detailed in the report’s content; Table S7: Evaluation tools used in the educational implementation of the analysed studies are described in detail in the report, presenting a comprehensive comparison among the various instruments and their application; Table S8: Treatment fidelity refers to the consistency of implementing the educational approach. The report provides a comprehensive description of each control element and indicator, detailing their comparative application across the various studies. Additionally, it includes the measurement factors and adjustment variables used in the pedagogical intervention in the analysed studies; Table S9: Limitations of the educational strategies addressed in the examined empirical studies. Each of these areas is detailed extensively in the main report. Refs. [119,120,121,122,123,124] are cited in the supplementary materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.-B., J.-N.G.-S., M.L.Á.-F. and S.M.d.B.-C.; methodology, A.D.-B., J.-N.G.-S., M.L.Á.-F. and S.M.d.B.-C.; software, A.D.-B., J.-N.G.-S., M.L.Á.-F. and S.M.d.B.-C.; validation, A.D.-B., J.-N.G.-S., M.L.Á.-F. and S.M.d.B.-C.; formal analysis, A.D.-B., J.-N.G.-S., M.L.Á.-F. and S.M.d.B.-C.; investigation, A.D.-B., J.-N.G.-S., M.L.Á.-F. and S.M.d.B.-C.; resources, A.D.-B., J.-N.G.-S., M.L.Á.-F. and S.M.d.B.-C.; data curation, A.D.-B., J.-N.G.-S., M.L.Á.-F. and S.M.d.B.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.-B., J.-N.G.-S., M.L.Á.-F. and S.M.d.B.-C.; writing—review and editing, A.D.-B., J.-N.G.-S., M.L.Á.-F. and S.M.d.B.-C.; visualization, A.D.-B., J.-N.G.-S., M.L.Á.-F. and S.M.d.B.-C.; supervision, A.D.-B., J.-N.G.-S., M.L.Á.-F. and S.M.d.B.-C.; project administration, A.D.-B., J.-N.G.-S., M.L.Á.-F. and S.M.d.B.-C.; funding acquisition, A.D.-B., J.-N.G.-S., M.L.Á.-F. and S.M.d.B.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The general operating funds of the universities have been used Universidad de León (Spain), Instituto Politécnico de Coimbra and NICSH (Portugal).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Núñez, M.; de Obesso, M.M.; Pérez, C.A. New challenges in higher education: A study of the digital competence of educator in COVID times. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 174, 121270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INTEF Marco Común de Competencia Digital Docente. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. 2017. Available online: https://bit.ly/2jqkssz (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- ISTE (Ed.) NETS for Teachers: National Educational Technology Standards for Teachers. 2008. Available online: https://bit.ly/2UaLExK (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- UNESCO Normas UNESCO Sobre Competencias en TIC Para Docentes. 2008. Available online: http://goo.gl/pGPDGv (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Hinojo, F.J.; Leiva, J.J. Competencia Digital e Interculturalidad: Hacia una Escuela Inclusiva y en Red. REICE Rev. Iberoam. Sobre Calid. Efic. Cambio Educ. 2022, 20, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattar, J.; Santos, C.C.; Cuque, L.M. Analysis and Comparison of International Digital Competence Frameworks for Education. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picón, G.A.; de Caballero, G.K.G.; Sánchez, J.N.P. Desempeño y formación docente en competencias digitales en clases no presenciales durante la pandemia COVID-19. Arandu UTIC 2021, 8, 139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Trigueros, I.M.; Binimelis, J. Aprender y enseñar con la escala del mapa para el profesorado de la “generación”: La competencia digital docente. Rev. Electrónica Recur. Internet Sobre Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2021, 238, 1–18. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10045/129434 (accessed on 23 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, N.; Mercader Rubio, I.; Trigueros Ramos, R.; Oropesa Ruiz, N.F.; García-Sánchez, J.N.; García Martín, J. Digital Competence, Use, Actions and Time Dedicated to Digital Devices: Repercussions on the Interpersonal Relationships of Spanish Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, D.H.; Levitt, J.T.; Bufka, L.F. The dissemination of empirically supported treatments: A view to the future. Behav. Res. Ther. 1999, 37, S147–S162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, A.; Correia, N.; Zaccoletti, S.; Daniel, J.R. Anxiety and social support as predictors of student academic motivation during the COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 644338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Jia, X.; Tao, R.; Dördüncü, H. COVID-19: A Source of Stress and Depression Among University Students and Poor Academic Performance. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 898556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacini, L.; Murat, M. Beyond the COVID-19 lockdown: Remote learning and education inequalities. Empirica 2023, 50, 207–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabero-Almenara, J.; Barragán-Sánchez, R.; Palacios-Rodríguez, A.; Martín-Párraga, L. Design and Validation of t-MOOC for the Development of the Digital Competence of Non-University Teachers. Technologies 2021, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pérez, S.; Cabero-Almenara, J.; Barroso-Osuna, J.; Palacios-Rodríguez, A. T-MOOC for initial teacher training in digital competences: Technology and educational innovation. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 846998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guajardo Leal, B.E.; Navarro-Corona, C.; Valenzuela González, J.R. Systematic mapping study of academic engagement in MOOC. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2019, 20, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Córdova, J.F.; Arriazu, R. El aprendizaje de competencias en los MOOC. Una revisión sistemática de la literatura. Rev. Latinoam. De Tecnol. Educ. 2023, 22, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlman, T.; Farrington, J. What is Sustainability? Sustainability 2010, 2, 3436–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattos, L.K.D.; Flach, L.; Costa, A.M.; Moré, R.P.O. Effectiveness and Sustainability Indicators in Higher Education Management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisiene, A.G.; Rapuano, V.; Raisys, S.J.; Lucinskaite-Sadovskiene, R. Teleworking Experience of Education Professionals vs. 623 Management Staff: Challenges Following Job Innovation. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2022, 2, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]