Chinese and British University Teachers’ Emotional Reactions to Students’ Disruptive Classroom Behaviors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Situational and Dispositional Antecedents of International Teachers’ Emotions

2.2. International Teachers’ Emotional Acculturation and Well-Being

2.3. Appraisals and Teachers’ Emotional Experiences

2.3.1. Goals

2.3.2. Certainty

2.3.3. Accountability

2.3.4. Coping Potential/Control

2.3.5. Values/Norms

2.4. Current Research

- Main question

- Subquestions

3. Study One: Questionnaire Survey

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Sample

3.1.2. Measures

3.1.3. Procedure

3.1.4. Analyses

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Correlation Analysis

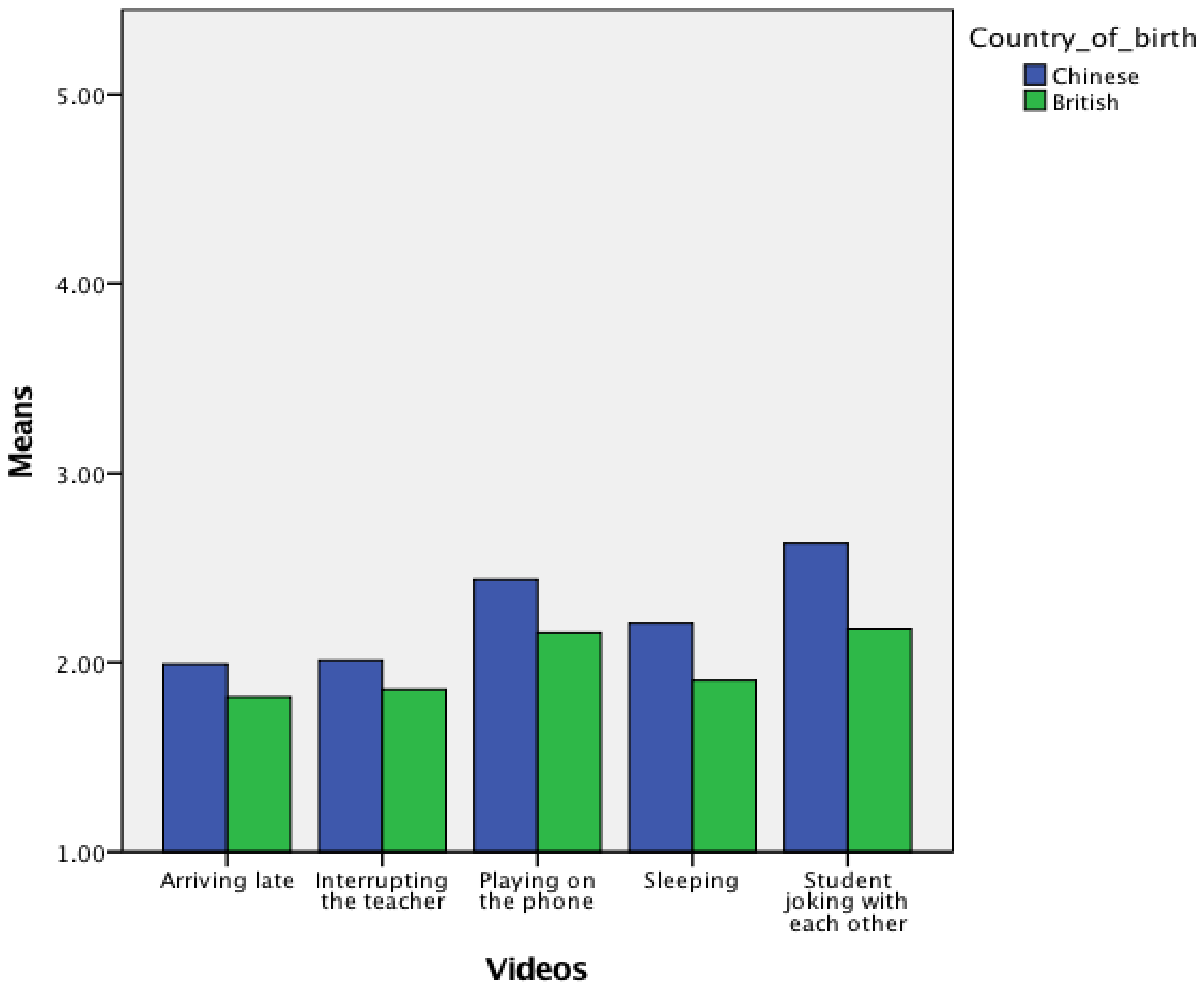

3.2.2. Comparisons between Chinese and British Teachers

4. Study Two: Interview Study

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Sample

4.1.2. Measures

- Why would Chinese teachers experience a significantly higher level of anxiety and shame than British teachers?

- What factors would influence Chinese and British teachers’ appraisals?

4.1.3. Procedure

4.1.4. Analyses

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Theme 1 Differences in the Appraisal Dimensions

…As a Chinese teacher I am not familiar with the environment. I am not a native, and I also have a lot of new rules I need to follow; sometimes I may want to discipline the student… but to be honest, if you put us in the situation I just mentioned, I dare not do what the British teachers had done.(Xiaoxia, Chinese)

So I don’t know if Chinese teachers may be new to the UK. And maybe their experience is completely different from our education and [they have] completely different undergraduate courses as well… I think the distress of teaching in a different country and the fact that [it] is [not] an easy comparison to your own undergraduate or whatever you know you did yourself back in higher education.(Frank, British)

Especially when some unexpected situations happen in their (Chinese teachers’) class, they don’t know how to react. For instance, here, if I see a student comes to my class late, I’m not sure if I should smile and say, “It’s ok”, and let them sit down or tell them, “You had better not be late next time”.(Anjun, Chinese)

I mean, if you’re teaching in a context which you’re not used to, you don’t really know how the students will behave or interact and how you’ll be judged. It is from the fear of being judged inadequate or sort of different.(Barbara, British)

So my guess is who feels responsible for the behavior. It could annoy you intentionally, but you may not feel responsible for that. However, if you feel somehow you’re responsible for it, then you’re going to feel more anxious about it. Let’s say somehow, it might be a question of who’s to blame.(Daniel, British)

Speaking of anxiety, Chinese teachers would like to link teaching outcomes to their performance. They may think, “I am the one who is teaching you. If you don’t learn well, maybe I have a bit [of] responsibility for that, too.”(Hanya, Chinese)

I suppose shame is something quite personal. I take the view that students are responsible for their own education. They chose to be there…So if somebody is not behaving professionally in a lecture, I don’t see that it’s my fault…and they need to learn how to behave.(Barbara, British)

I have a class every Friday morning. There are 13 students enrolled in it. But usually only 5 to 6 people show up, and sometimes even less. In this situation, the leading lecturer and the other teaching assistant always gave me support by telling me I should not take it personally because it’s Friday morning. Many students just could not get up early at the very end of the week.(Yuli, Chinese)

I personally think the class should be under my control; at least, I thought that way before I came to the UK. Later, after I got some training here, I realised that as a teacher, you are not only a controller, not only a teacher, but an assistant, a listener or a facilitator to your class. So, I think maybe Chinese teachers feel more anxious because they perceive the situation has gone beyond their controlling abilities.(Xiaoxia, Chinese)

4.2.2. Theme 2 Diversity of Cultural Values

The UK tends to be a, I think, quite individualistic society, and I think China is perhaps more community oriented or united. And so that’s perhaps why I tend to say if you’re not working hard, in fact it’s your problem, it’s not my problem. Maybe, I don’t know, I’m guessing, but in China [there is] more of the feeling that you have to, like, bring everybody else along.(Albert, British)

Speaking of shame, could it be because students did not give you the “face (respect)”? Take me as an example: even if the students behaved well in my class, I would still feel anxious because I would worry [about] if I performed well. It seems we Chinese really care about our “face” (figure in public).(Anjun, Chinese)

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion on the Quantitative Findings

5.2. Discussion on the Qualitative Findings

6. Conclusions

6.1. Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. The European Higher Education Area in 2015: Bologna Process: Implementation Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015; p. 308. [Google Scholar]

- Mayumi, K.; Zheng, Y. Becoming a speaker of multiple languages: An investigation into UK university students’ motivation for learning Chinese. Lang. Learn. J. 2023, 51, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HESA. Higher Education Staff Statistics: UK, 2021/22. In Annual; Higher Education Statistics Agency: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- HESA. Staff in Higher Education 2015/16. In Annual; Higher Education Statistics Agency: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- British Council. UK Parents: Mandarin ‘Most Beneficial’ Non-European Language. Available online: https://www.britishcouncil.org/contact/press/uk-parents-mandarin-most-beneficial-non-european-language (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Antoniadou, M.; Quinlan, K.M. Thriving on challenges: How immigrant academics regulate emotional experiences during acculturation. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doppen, F.H.; An, J. Student teaching abroad: Enhancing global awareness. Int. Educ. 2014, 43, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Pak, B. Pedagogical Challenges of Immigrant Minority Teacher Educators: A Collaborative Autoethnography Study. In To Be a Minority Teacher in a Foreign Culture: Empirical Evidence from an International Perspective; Mary Gutman, W.J., Beck, M., Bekerman, Z., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 285–300. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.-Y. “Crossing the River by Feeling the Stones”: Understanding Chinese Minority Teachers’ Transnational and Transitional Experiences. In To Be a Minority Teacher in a Foreign Culture: Empirical Evidence from an International Perspective; Mary Gutman, W.J., Beck, M., Bekerman, Z., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Yan, B. Chinese Immigrant Teachers in American Institutions of Higher Education: Challenge, Adaptation, and Development. DEStech Trans. Soc. Sci. Educ. Hum. Sci. 2017, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Howe, E.R. Teacher Acculturation Stories of Pathways to Teaching; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Alberts, H.C. The challenges and opportunities of foreign-born instructors in the classroom. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2008, 32, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, M. Mentoring, role modeling, and acculturation: Exploring international teacher narratives to inform supervisory practices. Res. Educ. Adm. Leadersh. 2020, 5, 640–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Di Napoli, R.; Borg, M.; Maunder, R.; Fry, H.; Walsh, E. Becoming and being an academic: The perspectives of Chinese staff in two research-intensive UK universities. Stud. High. Educ. 2010, 35, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L.; Lengyel, D. Research on minority teachers in Germany: Developments, focal points and current trends from the perspective of intercultural education. In To Be a Minority Teacher in a Foreign Culture: Empirical Evidence from an International Perspective; Mary Gutman, W.J., Beck, M., Bekerman, Z., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- Strasser, J. Germany: Professional Networks of Minority Teachers and Their Role in Developing Multicultural Schools. In To Be a Minority Teacher in a Foreign Culture: Empirical Evidence from an International Perspective; Mary Gutman, W.J., Beck, M., Bekerman, Z., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Yip, S.Y. Immigrant teachers’ experience of professional vulnerability. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2023, 51, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoebe, C.; Ellsworth, K.R.S. Appraisal Processes in Emotion. In Handbook of Affective Sciences; Richard, J., Davidson, K.R.S., Hill Goldsmith, H., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 572–595. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S. Emotion and Adaptation; Oxofrd University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R.; Frenzel, A.C.; Goetz, T.; Perry, R.P. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: An integrative approach to emotions in education. In Emotion in Education; Paul Schutz, R.P., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Roseman, I.J.; Smith, C.A. Appraisal theory: Overview, assumptions, varieties, controversies. In Appraisal Processes in Emotion: Theory, Methods, Research; Klaus, R., Scherer, A.S., Johnstone, T., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita, B.; Boiger, M.; De Leersnyder, J. The cultural construction of emotions. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 8, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Leersnyder, J.; Mesquita, B.; Kim, H.; Eom, K.; Choi, H. Emotional fit with culture: A predictor of individual differences in relational well-being. Emotion 2014, 14, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ward, C.; Geeraert, N. Advancing acculturation theory and research: The acculturation process in its ecological context. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 8, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Refining the teacher emotion model: Evidence from a review of literature published between 1985 and 2019. Camb. J. Educ. 2021, 51, 327–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenier, V.; Derakhshan, A.; Fathi, J. Emotion regulation and psychological well-being in teacher work engagement: A case of British and Iranian English language teachers. System 2021, 97, 102446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mérida-López, S.; Extremera, N. Emotional intelligence and teacher burnout: A systematic review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 85, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, A.C.; Daniels, L.; Burić, I. Teacher emotions in the classroom and their implications for students. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 56, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagenauer, G.; Hascher, T.; Volet, S.E. Teacher emotions in the classroom: Associations with students’ engagement, classroom discipline and the interpersonal teacher-student relationship. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2015, 30, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, H.; Montgomery, D. Exploring Korean and American teachers’ preferred emotional types. Roeper Rev. 2010, 32, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Exploring primary teacher emotions in Hong Kong and Mainland China: A qualitative perspective. Educ. Pract. Theory 2017, 39, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijda, N.H. The Emotions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Paula Niedenthal, S.K.-G.; Ric, F. Psychology of Emotion: Interpersonal, Experiential, and Cognitive Approaches; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, M.-L.; Taxer, J. Teacher emotion regulation strategies in response to classroom misbehavior. Teach. Teach. 2021, 27, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C. The dance of incivility in nursing education as described by nursing faculty and students. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2008, 31, E37–E54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, P.A.; Crowder, K.C.; White, V.E. The development of a goal to become a teacher. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 93, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirkov, V. Summary of the criticism and of the potential ways to improve acculturation psychology. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2009, 33, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucerain, M.M. Moving forward in acculturation research by integrating insights from cultural psychology. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2019, 73, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batja Mesquita, J.D.L.; Jasini, A. The cultural psychology of acculturation. In Handbook of Cultural Psychology, 2nd ed.; Dov Cohen, S.K., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 502–535. [Google Scholar]

- Eid, M.; Diener, E. Norms for experiencing emotions in different cultures: Inter- and intranational differences. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 869–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W.L.; Gabriel, S.; Lee, A.Y. “I” value freedom, but “we” value relationships: Self-construal priming mirrors cultural differences in judgment. Psychol. Sci. 1999, 10, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, D. Culture and self: An empirical assessment of Markus and Kitayama’s theory of independent and interdependent self-construals. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 2, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D.; Coon, H.M.; Kemmelmeier, M. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 3–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S.; Park, H.; Sevincer, A.T.; Karasawa, M.; Uskul, A.K. A cultural task analysis of implicit independence: Comparing North America, Western Europe, and East Asia. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 236–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Z.; Zhang, Z.; Bhatt, G.; Yum, Y.-O. Rethinking culture and self-construal: China as a middle land. J. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 146, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. Cross-cultural perspectives on personality. In Handbook of Personality Psychology; Robert Hogan, J.J., Briggs, S., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1997; pp. 439–464. [Google Scholar]

- Gundlach, M.; Zivnuska, S.; Stoner, J. Understanding the relationship between individualism–collectivism and team performance through an integration of social identity theory and the social relations model. Hum. Relat. 2006, 59, 1603–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gausel, N.; Leach, C.W. Concern for self-image and social image in the management of moral failure: Rethinking shame. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S.; Mesquita, B.; Karasawa, M. Cultural affordances and emotional experience: Socially engaging and disengaging emotions in Japan and the United States. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 890–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiger, M.; Deyne, S.D.; Mesquita, B. Emotions in “the world”: Cultural practices, products, and meanings of anger and shame in two individualist cultures. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mosquera, P.M.R.; Manstead, A.S.; Fischer, A.H. The role of honor-related values in the elicitation, experience, and communication of pride, shame, and anger: Spain and the Netherlands compared. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 26, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Leersnyder, J. Emotional acculturation: A first review. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 17, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, L. Psychology and Culture: Thinking, Feeling and Behaving in a Global Context; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- De Leersnyder, J.; Kim, H.S.; Mesquita, B. My emotions belong here and there: Extending the phenomenon of emotional acculturation to heritage culture fit. Cogn. Emot. 2020, 34, 1573–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leersnyder, J.; Mesquita, B.; Kim, H.S. Where do my emotions belong? A study of immigrants’ emotional acculturation. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kafetsios, K.G. Interdependent self-construal moderates relationships between positive emotion and quality in social interactions: A case of person to culture fit. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kateri, E.; Papastylianou, D.; Karademas, E. Perceived Discrimination and Psychological Well-Being Among Immigrants Living in Greece: Separation as Mediator and Interdependence as Moderator. Eur. J. Psychol. 2022, 18, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leersnyder, J.; Kim, H.; Mesquita, B. Feeling right is feeling good: Psychological well-being and emotional fit with culture in autonomy-versus relatedness-promoting situations. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peeters, M.C.; Oerlemans, W.G. The relationship between acculturation orientations and work-related well-being: Differences between ethnic minority and majority employees. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2009, 16, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrid, S.; Baldwin, N.; Belbase, S. Feeling culture: The emotional experience of six early childhood educators while teaching in a cross-cultural context. Glob. Stud. Child. 2016, 6, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, B.; Frijda, N.; Scherer, K. Culture and Emotion, Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology Vol. 2: Basic Processes and Developmental Psychology; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Karandashev, V. Cultural Models of Emotions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Klassen, R.M.; Chiu, M.M. The occupational commitment and intention to quit of practicing and pre-service teachers: Influence of self-efficacy, job stress, and teaching context. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 36, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijda, N.H. The Laws of Emotion; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, K.R. The nature and study of appraisal: A review of the issues. In Appraisal Processes in Emotion: Theory, Methods, Research; Klaus, R., Scherer, A.S., Johnstone, T., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 369–391. [Google Scholar]

- Anne, C.; Frenzel, T.G.; Elizabeth, J.; Stephens, B.J. Antecedents and effects of teachers’ emotional experiences: An integrated perspective and empirical test. In Advances in Teacher Emotion Research; Paul, A., Schutz, M.Z., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 129–151. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R.E.; Wheatley, K.F. Teachers’ emotions and teaching: A review of the literature and directions for future research. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 15, 327–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.; Schutz, L.P.A.; Meca, R. Williams-Johnson Educational psychology perspectives on teachers’ emotions. In Advances in Teacher Emotion Research; Paul, A., Schutz, M.Z., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Roseman, I.J. Cognitive determinants of emotion: A structural theory. In Review of Personality & Social Psychology; Shaver, P., Ed.; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1984; Volume 5, pp. 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.A.; Ellsworth, P.C. Patterns of cognitive appraisal in emotion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 48, 813–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Lazarus, R.S. Appraisal components, core relational themes, and the emotions. Cogn. Emot. 1993, 7, 233–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R.; Hoyle, R.H. Situations, dispositions, and the study of social behavior. In Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R.; Goetz, T.; Perry, R.P. Achievement emotions questionnaire (AEQ). In User’s Manual; University of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zmud, J.; Lee-Gosselin, M.; Munizaga, M.; Carrasco, J.A. Transport Survey Methods: Best Practice for Decision Making; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ivankova, N.V.; Creswell, J.W.; Stick, S.L. Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: From theory to practice. Field Methods 2006, 18, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, C. Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-Researchers; Wiley-Blackwell: West Sussex, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educ. Res. 2004, 33, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wheldall, K.; Merrett, F. Which classroom behaviours do primary school teachers say they find most troublesome? Educ. Rev. 1988, 40, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Kulm, G. Chinese teachers’ perceptions of students’ classroom misbehaviour. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.; Leung, J. Disruptive classroom behaviors of secondary and primary school students. Educ. Res. J. 2002, 17, 219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R.; Goetz, T.; Frenzel, A.C.; Barchfeld, P.; Perry, R.P. Measuring emotions in students’ learning and performance: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ). Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 36, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, O.B.; Boschi-Pinto, C.; Lopez, A.D.; Murray, C.J.; Lozano, R.; Inoue, M. Age Standardization of Rates: A New WHO Standard; (GPE Discussion Paper Series: No. 31); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, A.Y.; Jim, C.Y. Citizen attitude and expectation towards greenspace provision in compact urban milieu. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frenzel, A.C.; Thrash, T.M.; Pekrun, R.; Goetz, T. Achievement emotions in Germany and China: A cross-cultural validation of the Academic Emotions Questionnaire—Mathematics. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2007, 38, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luxon, T.; Peelo, M. Academic sojourners, teaching and internationalisation: The experience of non-UK staff in a British University. Teach. High. Educ. 2009, 14, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, A.C.; Goetz, T.; Lüdtke, O.; Pekrun, R.; Sutton, R.E. Emotional transmission in the classroom: Exploring the relationship between teacher and student enjoyment. J. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 101, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiang, Y. Negotiating professional identities in teaching language abroad: An inquiry of six native Chinese teachers in Britain. Lang. Learn. J. 2021, 49, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.E.; Oxley, L.; Asbury, K. “My brain feels like a browser with 100 tabs open”: A longitudinal study of teachers’ mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 92, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitayama, S.; Park, H. Cultural shaping of self, emotion, and well-being: How does it work? Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2007, 1, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katana, M.; Röcke, C.; Spain, S.M.; Allemand, M. Emotion regulation, subjective well-being, and perceived stress in daily life of geriatric nurses. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dewaele, J.-M.; Wu, A. Predicting the emotional labor strategies of Chinese English Foreign Language teachers. System 2021, 103, 102660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Country of birth | - | −0.08 | −0.24 * | −0.14 | −0.31 ** | −0.20 | 0.08 |

| 2 Anger | - | - | 0.67 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.72 ** |

| 3 Anxiety | - | - | - | 0.77 ** | 0.71 ** | 0.62 ** | 0.52 * |

| 4 Hopelessness | - | - | - | - | 0.70 ** | 0.72 ** | 0.51 ** |

| 5 Shame | - | - | - | - | - | 0.80 ** | 0.35 ** |

| 6 Sadness | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.37 ** |

| 7 Annoyance | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Age | - | −0.14 | −0.22 * | −0.17 | −0.24 * | −0.07 | 0.02 |

| 2 Anger | - | - | 0.67 ** | 0.63 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.72 ** |

| 3 Anxiety | - | - | - | 0.78 ** | 0.71 ** | 0.62 ** | 0.52 * |

| 4 Hopelessness | - | - | - | - | 0.70 ** | 0.72 ** | 0.51 ** |

| 5 Shame | - | - | - | - | - | 0.80 ** | 0.35 ** |

| 6 Sadness | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.37 ** |

| 7 Annoyance | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Chinese Teachers | British Teachers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | η2 | p | |

| Anger | 2.58 | 0.94 | 2.43 | 1.02 | - | 0.48 |

| Anxiety | 2.12 | 1.01 | 1.67 | 0.83 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| Hopelessness | 1.99 | 0.93 | 1.71 | 0.96 | - | 0.18 |

| Shame | 1.90 | 1.03 | 1.36 | 0.67 | 0.10 | 0.00 |

| Sadness | 1.91 | 0.99 | 1.57 | 0.74 | - | 0.07 |

| Annoyance | 3.04 | 0.91 | 3.12 | 0.92 | - | 0.46 |

| Chinese Teachers | British Teachers | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 7 | 6 | 13 |

| Gender | F = 6, M = 1 | F = 1, M = 5 | F = 7, M = 6 |

| Age (mean/SD) | 28.29/5.01 | 45.50/12.88 | 36.23/12.80 |

| Years of teaching in the UK (mean/SD) | 2.10/2.07 | 16.33/12.46 | 8.66/11.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, X.; Klassen, R.M. Chinese and British University Teachers’ Emotional Reactions to Students’ Disruptive Classroom Behaviors. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511798

Xu X, Klassen RM. Chinese and British University Teachers’ Emotional Reactions to Students’ Disruptive Classroom Behaviors. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511798

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Xinyuan, and Robert M. Klassen. 2023. "Chinese and British University Teachers’ Emotional Reactions to Students’ Disruptive Classroom Behaviors" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511798

APA StyleXu, X., & Klassen, R. M. (2023). Chinese and British University Teachers’ Emotional Reactions to Students’ Disruptive Classroom Behaviors. Sustainability, 15(15), 11798. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511798