Emerging Dynamics of Training, Recruiting and Retaining a Sustainable Maritime Workforce: A Skill Resilience Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Human Resource (HR) Practices among Employers

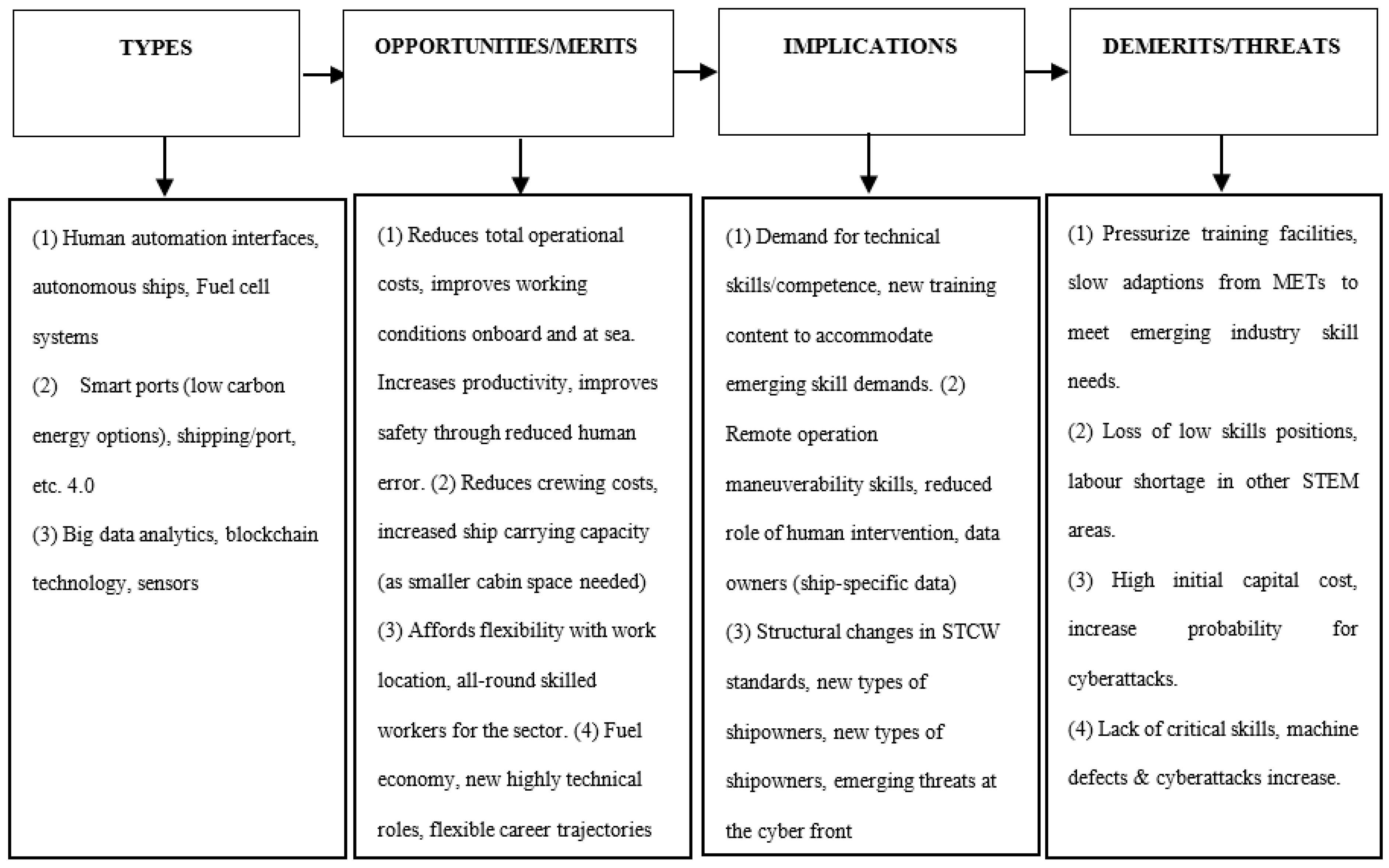

2.2. Industry Automation and Labour Implications

3. Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptives

4.2. Entry into the Workforce

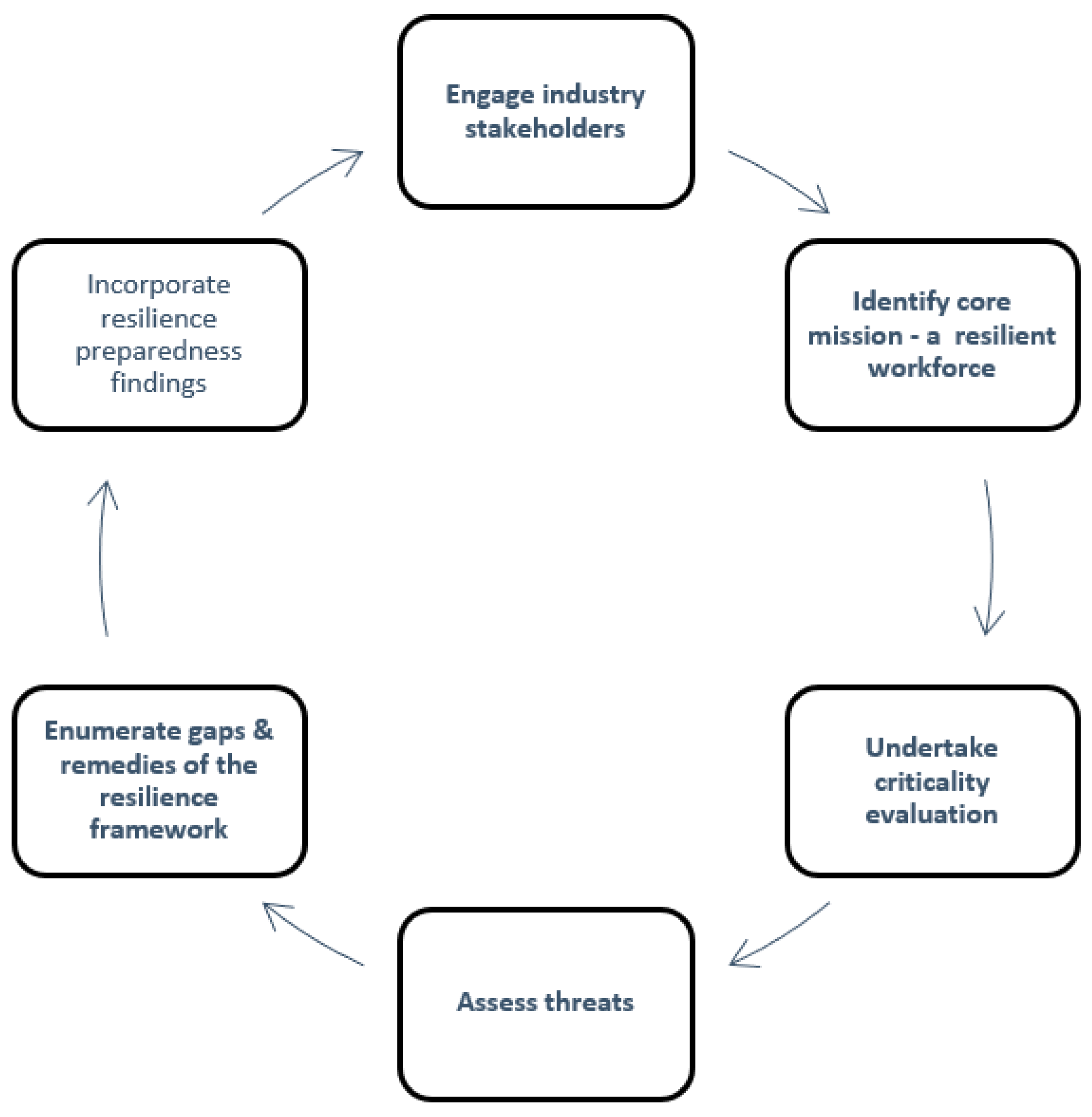

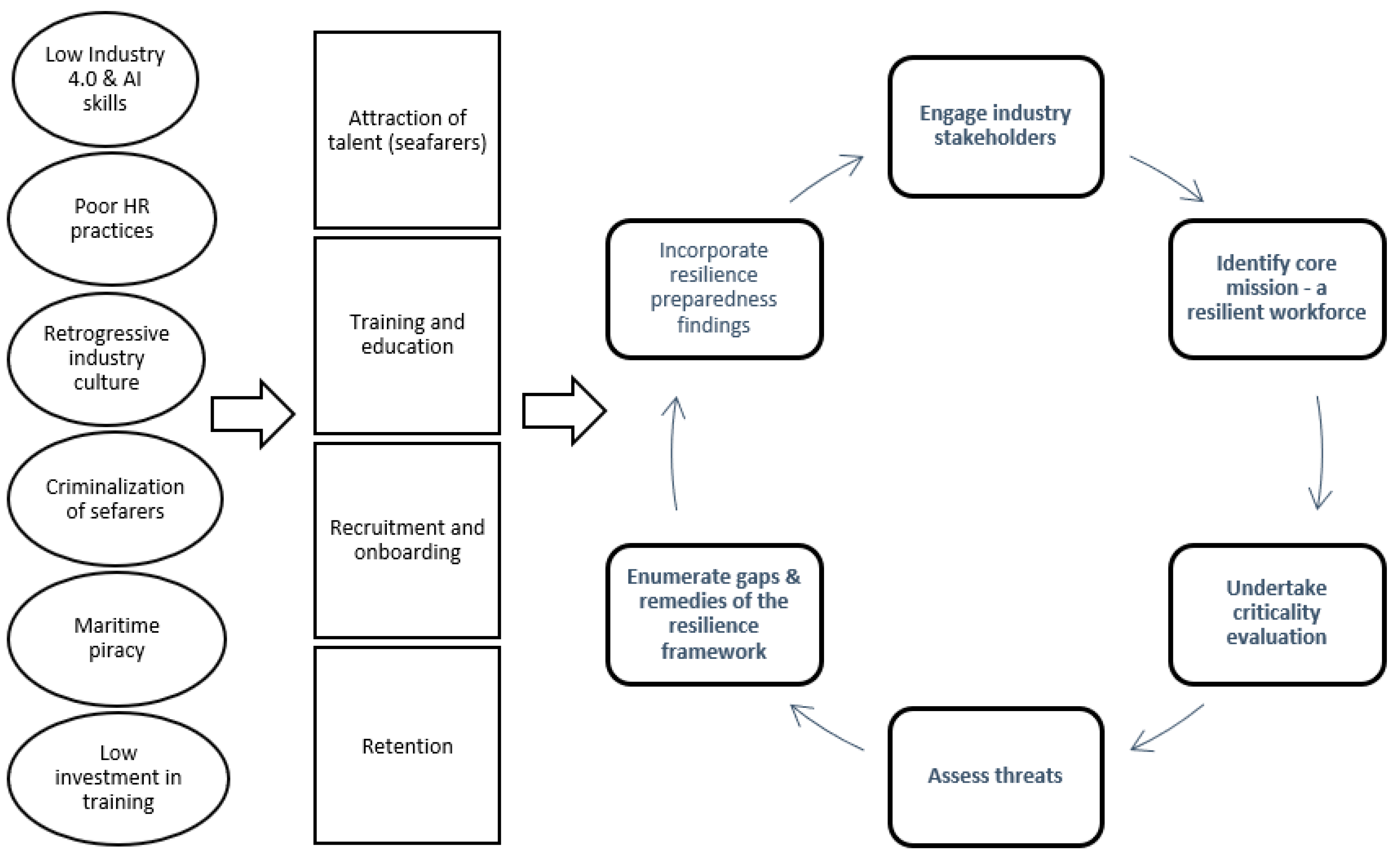

4.3. Framework for Building Resilience

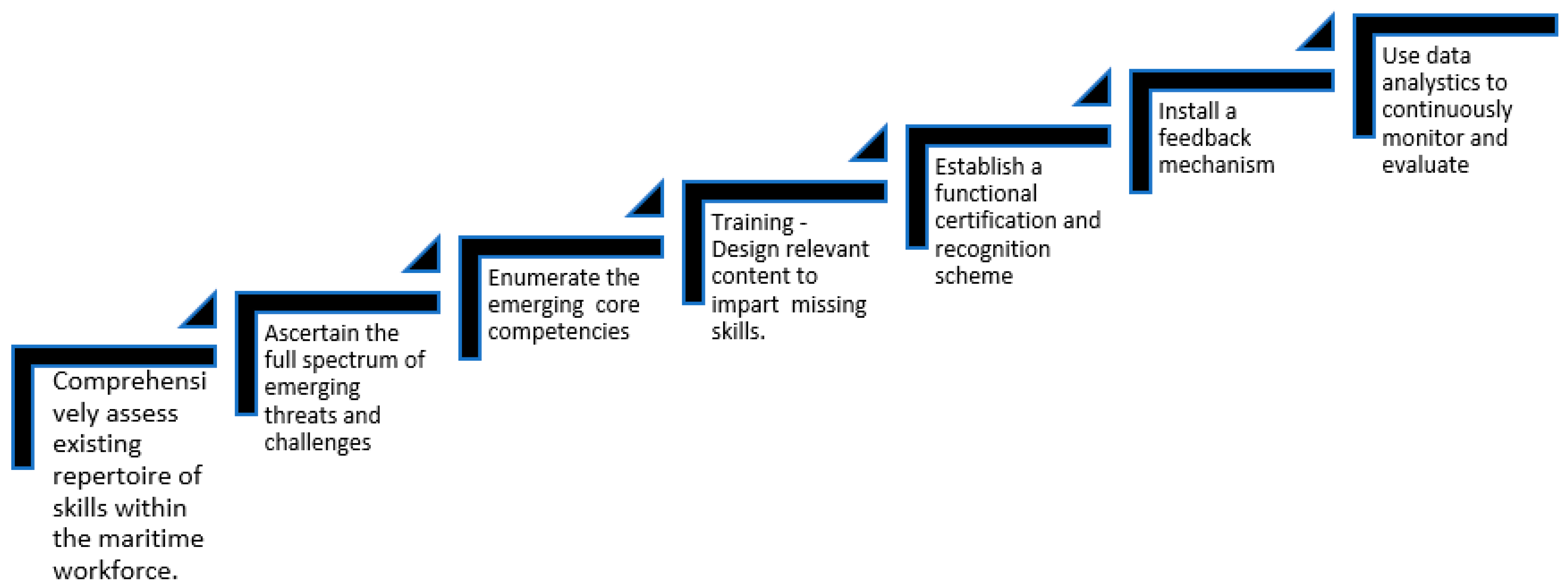

5. Conclusions and Policy Considerations

- All stakeholders of the maritime transportation sector, especially employers, must take a long-term approach to developing skilled talents to meet the aggregate workforce demands. This is a more sustainable approach to developing human capital for the sector and will help ameliorate or overcome the many challenges to which Industry 4.0 imperatives expose the sector. It therefore means that traditional, reactionary and short-term HR practices such as short-term contracts and poaching of highly skilled talents (e.g., officers of specialized tankers) will need to be phased out, giving way to employee-centred programmes in which the entire career lifecycle of the workforce is given the preeminence. Any workplace design in this regard needs to focus on building the capability of the workforce and equipping them with amphibious skills to easily alternate between shipside and portside job roles;

- The maritime transportation sector needs a concerted sustainable approach to training the workforce. This underscores an importation (from general human resource practice circles) and meticulous application of sustainable HRM concepts. This encapsulates a rethink of existing training models for the workforce, fairness and equity concerning pay/conditions of service, among other things. The current practice where seafarer pay and conditions of service differ depending on nationality and ethnicity will not inure to the benefit of the maritime transportation sector and is certainly a threat to its sustainability. Thus, pursuing a sustainable HRM strategy not only leads to the retention of highly skilled talents within the workforce but also strengthens the attraction of very gifted people within the Generation Y and Z brackets to the sector. Already, there is strong competition between maritime transportation and other sectors (IT, AI and other landside roles) for talents in the younger generation brackets;

- Given that the transition towards digitalization of the sector is revolutionary and inevitable, the syllabus and training content of Maritime Education Training establishments will need a paradigm shift. As part of the wider global supply chain, which is also undergoing intensive digitalization, maritime transportation is exposed to new risks such as maritime cyber security. Also, the emergence of automated ships and smart ports only increases the probability of cyber-attacks. New training content must cater for cyber awareness training for seafarers and port workers, among other things. This is part of the compendium of changes needed to build resilience in the workforce for the maritime transportation sector. There is thus an urgent need for content revision/overhaul to equip future graduates of maritime colleges with holistic and futuristic skill sets. Since building resilience inherently hinges on intellectual capabilities, training institutes must work together with sector employers and other stakeholders to unearth the specific cybersecurity skill sets lacking and what is needed to produce a cyber-resilient maritime-related workforce. Future competence demands will be mostly in the area of technology, and this has to be infused into the training curriculum in time to prepare the right number and mix of skills for a sustainable maritime transport sector. Further, new training content will need to consider the transfer of technical, critical reasoning and problem-solving skills to realize an analytical workforce.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gekara, V.O.; Sampson, H. The World of the Seafarer: Qualitative Accounts of Working in the Global Shipping Industry; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Slišković, A.; Juranko, A. Dual life of seafarers’ families: Descriptive study of perspectives of seafarers’ partners. Community Work. Fam. 2019, 22, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. Review of Maritime Transport 2022. 2022. Available online: https://unctad.org/rmt2022 (accessed on 8 April 2023).

- Liu, K.; Yu, Q.; Yuan, Z.; Yang, Z.; Shu, Y. A systematic analysis for maritime accidents causation in Chinese coastal waters using machine learning approaches. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2021, 213, 105859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, T.R.; Adebambo, O.; Feijoo, M.C.; Elhaimer, E.; Hossain, T.; Edwards, S.J.; Morrison, C.E.; Romo, J.; Sharma, N.; Taylor, S.; et al. Environmental effects of marine transportation. In World Seas: An Environmental Evaluation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 505–530. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder-Hinrichs, J.U.; Song, D.W.; Fonseca, T.; Lagdami, K.; Shi, X.; Loer, K. Transport 2040: Automation, Technology, Employment-The Future of Work; World Maritime University: Malmo, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Notteboom, T.; Pallis, A.; Rodrigue, J.-P. Port Economics, Management and Policy; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jo, S.; D’agostini, E. Disrupting technologies in the shipping industry: How will MASS development affect the maritime workforce in Korea. Mar. Policy 2020, 120, 104139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, O. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Sustainability of the Maritime Labour Force. In The Transformation of Global Trade in a New World; Marco-Lajara, B., Özer, A.C., Falcó, J.M., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 158–179. [Google Scholar]

- Kotcharin, S.; Maneenop, S. Geopolitical risk and corporate cash holdings in the shipping industry. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 136, 101862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benamara, H.; Hoffmann, J.; Youssef, F. Maritime transport: The sustainability imperative. In Sustainable Shipping: A Cross-Disciplinary View; Psaraftis, H., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, K.; Su, C.W.; Tao, R.; Umar, M. How do geopolitical risks affect oil prices and freight rates? Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2021, 215, 105955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, H. Wider implications of autonomous vessels for the maritime industry: Mapping the unprecedented challenges. In Advances in Transport Policy and Planning; Milakis, D., Thomopoulos, N., Wee, B.V., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 263–289. [Google Scholar]

- Ampah, J.D.; Yusuf, A.A.; Afrane, S.; Jin, C.; Liu, H. Reviewing two decades of cleaner alternative marine fuels: Towards IMO’s decarbonization of the maritime transport sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesar, L.D.; Cahoon, S.; Fei, J.; Sallah, C. A Exploring the antecedents of high mobility among ship officers: Empirical evidence from Australia. Marit. Policy Manag. 2021, 48, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, J. (Ed.) Managing Human Resources in the Shipping Industry; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Zhang, P. Human Resource Management in Shipping: Issues, Challenges, and Solutions; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Andrei, D.M.; Griffin, M.A.; Grech, M.; Neal, A. How demands and resources impact chronic fatigue in the maritime industry. The mediating effect of acute fatigue, sleep quality and recovery. Saf. Sci. 2020, 121, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesar, D.L. The global shortage of ship officers: An investigation of the complexity of retention issues among Australian seafarers. In Australian Maritime College, University of Tasmania; University of Tasmania: Launceston, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- BIMCO/ICS. The Global Supply and Demand for Seafarers in 2021; BIMCO: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev, P.; Soares, C.G. (Eds.) Sustainable Development and Innovations in Marine Technologies. In Proceedings of the 18th International Congress of the Maritme Association of the Mediterranean (IMAM 2019), Varna, Bulgaria, 9–11 September 2019; CRC Press: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.E.; Sharma, A.; Gausdal, A.H.; Chae, C.J. Impact of automation technology on gender parity in maritime industry. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2019, 18, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silos, J.M.; Piniella, F.; Monedero, J.; Walliser, J. Trends in the global market for crews: A case study. Mar. Policy 2012, 36, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogusławski, K.; Gil, M.; Nasur, J.; Wróbel, K. Implications of autonomous shipping for maritime education and training: The cadet’s perspective. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2022, 24, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, K.; Song, D.-W. Maritime logistics for the next decade: Challenges, opportunities and required skills. In Global Logistics and Supply Chain Strategies for the 2020s: Vital Skills for the Next Generation; Merkert, R., Hoberg, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Caesar, L.D.; Cahoon, S.; Fei, J. Understanding the complexity of retention among seafarers: A perspective of Australian employers. Aust. J. Marit. Ocean. Aff. 2020, 12, 16–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesar, L.D.; Cahoon, S.; Fei, J. Exploring the range of retention issues for seafarers in global shipping: Opportunities for further research. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2015, 14, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lottum, J.; Van Zanden, J.L. Labour productivity and human capital in the European maritime sector of the eighteenth century. Explor. Econ. Hist. 2014, 53, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanowska, B.B.; Kozłowski, A.; Dąbrowski, J.; Klimek, H. Seaport innovation trends: Global insights. Mar. Policy 2023, 152, 105585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabić, M.; Maley, J.F.; Švarc, J.; Poček, J. Future of digital work: Challenges for sustainable human resources management. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’agostini, E.; Ryoo, D.-K.; Jo, S.-H. A study on Korean seafarer’s perceptions towards unmanned ships. J. Navig. Port Res. 2017, 41, 381–388. [Google Scholar]

- Tester, K. Technology in Shipping: The Impact of Technological Change on the Shipping Industry; Clyde & Co.: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, L.Y.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Yuen, K.F. Key knowledge domains for maritime shipping executives in the digital era: A knowledge-based view approach. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbakhsh, M.; Emad, G.R.; Cahoon, S. Industrial revolutions and transition of the maritime industry: The case of Seafarer’s role in autonomous shipping. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2022, 38, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emad, G.R.; Shahbakhsh, M. Digitalization Transformation and its Challenges in Shipping Operation: The Case of Seafarers Cognitive Human Factor. Adv. Transp. 2022, 60, 684–690. [Google Scholar]

- Heering, D.; Maennel, O.; Venables, A. Shortcomings in cybersecurity education for seafarers. In Developments in Maritime Technology and Engineering; Soares, C.G., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Zikmund, W.G.; Babin, B.J.; Carr, J.C.; Griffin, M. Business Research Methods; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, T. Gaining and maintaining access: Exploring the mechanisms that support and challenge the relationship between gatekeepers and researchers. Qual. Soc. Work. 2011, 10, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, S.; Grace, R.; Llewellyn, G. Negotiating with gatekeepers in research with disadvantaged children: A case study of children of mothers with intellectual disability. Child. Soc. 2016, 30, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzon, A.; Bayart, C. Workshop Synthesis: Web-based surveys, new insight to address main challenges. Transp. Res. Procedia 2018, 32, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D. Design effects in the transition to web-based surveys. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 32, S90–S96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, B.B.; Hardie, T.L. Readability of advance directive documents. Image J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 1997, 29, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, T.M. Response rates to expect from web-based surveys and what to do about it. J. Ext. 2008, 46, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kitada, M. Women seafarers: An analysis of barriers to their employment. In The World of the Seafare; Gekara, V.O., Sampson, H., Eds.; Springer: Malmo, Sweden, 2021; pp. 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, K.; Wadsworth, E.; Honebon, S.; Broadhurst, E.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, P. Gender in the maritime space: How can the experiences of women seafarers working in the UK shipping industry be improved? J. Navig. 2021, 74, 1238–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.C.; Emad, G.R.; Fei, J. Key factors impacting women seafarers’ participation in the evolving workplace: A qualitative exploration. Mar. Policy 2023, 148, 105407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Li, Y.; Zheng, G.; Zhang, P. Exploring into contributing factors to young seafarer turnover: Empirical evidence from China. J. Navig. 2021, 74, 914–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.H.; Hur, H.; Ho, Y.; Yoo, S.; Yoon, S.W. Workforce resilience: Integrative review for human resource development. Perform. Improv. Q. 2020, 33, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afenyo, M.; Caesar, L.D. Maritime cybersecurity threats: Gaps and directions for future research. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2023, 236, 106493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesar, L.D.; Fei, J. Recruitment and the image of the shipping industry. In Managing Human Resources in the Shipping Industry; Fei, J., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon, UK, 2018; pp. 18–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, F.L.; Wood, G.; Wang, M.; Li, A.S. Riding the tides of mergers and acquisitions by building a resilient workforce: A framework for studying the role of human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2021, 31, 100747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moenkemeyer, G.; Hoegl, M.; Weiss, M. Innovator resilience potential: A process perspective of individual resilience as influenced by innovation project termination. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 627–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Sub-Category | Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–33 yrs | 39 | 19.7 | 21.9 |

| 34–46 yrs | 64 | 32.3 | 36.0 | |

| 47–65 yrs | 65 | 32.8 | 36.5 | |

| Over 65 yrs | 10 | 5.1 | 5.6 | |

| Total | 178 | 89.9 | ||

| Missing value | 20 | 10.1 | ||

| Total | 198 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Gender | Male | 176 | 88.9 | 98.9 |

| Female | 2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | |

| Total | 178 | 89.9 | ||

| Missing value | 20 | 10.1 | ||

| Total | 198 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Job category | Cadet | 2 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| Integrated rating | 6 | 3.0 | 3.4 | |

| Officer | 122 | 61.6 | 68.5 | |

| Master | 48 | 24.2 | 27.0 | |

| Total | 178 | 89.9 | ||

| Missing value | 20 | 10.1 | ||

| Total | 198 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Family status | Married | 120 | 60.6 | 67.4 |

| Single | 18 | 9.1 | 10.1 | |

| Divorces/separated | 14 | 7.1 | 7.9 | |

| In a relationship | 26 | 13.1 | 14.6 | |

| Total | 178 | 89.9 | ||

| Missing value | 20 | 10.1 | ||

| Total | 198 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Department | Deck | 105 | 53.0 | 59.0 |

| Engine | 48 | 24.2 | 27.0 | |

| Other | 25 | 12.6 | 14.0 | |

| Total | 178 | 89.9 | ||

| Missing value | 20 | 10.1 | ||

| Total | 198 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Category | Sub-Category | Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company Type | Shipping company | 101 | 51.0 | 58.7 |

| Manning Company | 42 | 21.2 | 24.4 | |

| Ship managing company | 29 | 14.6 | 16.9 | |

| Total | 172 | 86.9 | ||

| Missing value | 26 | 13.1 | ||

| Total | 198 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| Yrs of experience | 5 yrs or less | 13 | 6.6 | 7.3 |

| 6–10 yrs | 35 | 17.7 | 19.7 | |

| 11–20 yrs | 55 | 27.8 | 30.9 | |

| Over 20 yrs | 75 | 37.9 | 42.1 | |

| Total | 178 | 89.9 | ||

| Missing value | 20 | 10.1 | ||

| Total | 198 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| AOBS | 15–20 yrs | 116 | 58.6 | 65.2 |

| 21–26 yrs | 39 | 19.7 | 21.9 | |

| 27–32 yrs | 9 | 4.5 | 5.1 | |

| 33–38 yrs | 7 | 3.5 | 3.9 | |

| 39–45 yrs | 7 | 3.5 | 3.9 | |

| Total | 178 | 89.9 | ||

| Missing value | 20 | 10.1 | ||

| Total | 198 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |

| LOPS | 5 yrs or less | 20 | 10.1 | 11.5 |

| 6–10 yrs | 23 | 11.6 | 13.2 | |

| 11–20 yrs | 52 | 26.3 | 29.9 | |

| Lifetime | 79 | 39.9 | 45.4 | |

| Total | 174 | 87.9 | ||

| Missing value | 24 | 12.1 | ||

| Total | 198 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Length of Period Intending to Work in Shipping as a Seafarer (Years) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Sub-category | 5 yrs or less | 6–10 yrs | 11–20 yrs | Lifetime | Total |

| Age | 18–33 yrs | 5 (12.8%) | 4 (10.3%) | 18 (46.2%) | 12 (30.8) | 39 (100.0%) |

| 34–46 yrs | 9 (14.3%) | 13 (20.6%) | 15 (23.8%) | 26 (41.3%) | 63 (100.0%) | |

| 47–65 yrs | 2 (3.2%) | 6 (9.5%) | 19 (30.2%) | 36 (57.1%) | 63 (100.0%) | |

| Over 65 yrs | 4 (44.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (55.6%) | 9 (100.0) | |

| Total | 20 (11.5%) | 23 (13.2%) | 52 (29.9%) | 79 (45.4%) | 174 (100.0) | |

| Years of experience | 5 yrs or less | 2 (15.4%) | 2 (15.4%) | 6 (46.2%) | 3 (23.1%) | 13 (100.0%) |

| 6–10 yrs | 4 (11.4%) | 12 (34.3%) | 11 (31.4%) | 8 (22.9%) | 35 (100.0%) | |

| 11–20 yrs | 6 (11.1%) | 5 (9.3%) | 26 (48.1%) | 17 (31.5%) | 54 (100.0%) | |

| Over 20 yrs | 8 (11.1%) | 4 (5.6%) | 9 (12.5%) | 51 (70.8%) | 72 (100.0%) | |

| Total | 20 (11.5%) | 23 (13.2%) | 52 (29.9%) | 79 (45.4%) | 174 (100.0%) | |

| Family status | Married | 15 (12.9%) | 19 (16.4%) | 30 (25.9%) | 52 (44.8%) | 116 (100.0%) |

| Single | 3 (16.7%) | 2 (11.1%) | 6 (33.3%) | 7 (38.9%) | 18 (100.0%) | |

| Divorced/separated | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (42.9%) | 8 (57.1%) | 14 (100.0%) | |

| In a relationship | 2 (7.7%) | 2 (7.7%) | 10 (38.5%) | 12 (46.2%) | 26 (100.0%) | |

| Total | 20 (11.5%) | 23 (13.2%) | 52 (29.9%) | 79 (45.4%) | 174 (100.0%) | |

| Factor | Number | Mean | Rank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1.2 | Interest in the lifestyle at sea | 198 | 3.94 | 1 |

| A1.1 | Prospect of earning good salary/wages | 197 | 3.84 | 2 |

| A1.9 | Opportunity to travel | 197 | 3.84 | 3 |

| A1.7 | Availability of career prospects and opportunities for advancement | 197 | 3.59 | 4 |

| A1.8 | Pride and prestige for the position of ship master | 197 | 3.02 | 5 |

| A1.5 | Growing up in a coastal town | 197 | 2.84 | 6 |

| A1.6 | Influence from friends and colleagues | 197 | 2.56 | 7 |

| A1.4 | Influence from parents | 197 | 2.34 | 8 |

| A1.10 | Other | 189 | 2.24 | 9 |

| A1.3 | A family tradition | 197 | 2.20 | 10 |

| (a) | ||||

| Component | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| D7.1 Poor working conditions onboard | 0.738 | |||

| D7.2 Lack of new and fresh challenges | 0.651 | |||

| D7.4 Lack of opportunities for training | 0.702 | |||

| D7.5 Lack of opportunities for progression to higher ranks onboard | 0.770 | |||

| D7.6 Continual refusal of shore leave during port hours | 0.506 | |||

| D7.7 Lack of recreational facilities onboard | 0.649 | |||

| D7.8 Dissatisfaction with the employer | 0.800 | |||

| D7.9 Lack of a supportive organisational culture | 0.875 | |||

| D7.10 Bullying from superiors or workmates onboard | 0.796 | |||

| D7.11 Inability to contact family from sea | 0.600 | |||

| D7.12 Poor mentoring from superiors onboard | 0.769 | |||

| D9.1 Late payment of salary | 0.865 | |||

| D9.3 Salary not increasing within an expected period | 0.706 | |||

| D9.4 Persistent failure of employer to pay salary due to financial problems | 0.832 | |||

| D9.5 Lack of long service bonuses | 0.743 | |||

| D9.6 Problems with being granted sick leave | 0.856 | |||

| D9.8 Lack of compensation schemes | 0.634 | |||

| D9.9 Poor food onboard | 0.552 | |||

| D8.1 Jailing of seafarers for operational error | 0.624 | |||

| D8.3 Small crew size onboard | 0.635 | |||

| D8.4 Too much paperwork to be done per voyage | 0.846 | |||

| D8.5 Loneliness while at sea | 0.541 | |||

| D8.7 Onboard fatigue | 0.700 | |||

| D8.9 Lack of adequate rest | 0.590 | |||

| D8.10 Staying long time at sea away from family | 0.536 | |||

| D8.11 Too much workload onboard | 0.770 | |||

| D8.14 Availability of job opportunities on land | 0.540 | |||

| D6.1 To live in a relationship | 0.811 | |||

| D6.2 Desire to start a family | 0.876 | |||

| D6.3 To care for aging parents | 0.761 | |||

| D6.4 Family stress | 0.783 | |||

| D6.5 Financial stress | 0.752 | |||

| D6.7 Desire to work on land | 0.616 | |||

| (b) | ||||

| Component | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| D7.1 Poor working conditions onboard | 0.757 | |||

| D7.2 Lack of new and fresh challenges | 0.521 | |||

| D7.4 Lack of opportunities for training | 0.751 | 0.556 | ||

| D7.5 Lack of opportunities for progression to higher ranks onboard | 0.772 | 0.514 | ||

| D7.6 Continual refusal of shore leave during port hours | 0.667 | 00.511 | ||

| D7.7 Lack of recreational facilities onboard | 0.783 | 0.527 | 0.541 | |

| D7.8 Dissatisfaction with the employer | 0.770 | |||

| D7.9 Lack of a supportive organisational culture | 0.857 | 0.517 | ||

| D7.10 Bullying from superiors or workmates onboard | 0.777 | 0.570 | ||

| D7.11 Inability to contact family from sea | 0.750 | 0.613 | ||

| D7.12 Poor mentoring from superiors onboard | 0.820 | 0.598 | ||

| D9.1 Late payment of salary | 0.522 | 0.854 | ||

| D9.3 Salary not increasing within an expected period | 0.744 | |||

| D9.4 Persistent failure of employer to pay salary due to financial problems | 0.576 | 0.860 | ||

| D9.5 Lack of long service bonuses | 0.519 | 0.801 | ||

| D9.6 Problems with being granted sick leave | 0.602 | 0.894 | ||

| D9.8 Lack of compensation schemes | 0.597 | 0.782 | ||

| D9.9 Poor food onboard | 0.627 | 0.729 | ||

| D8.1 Jailing of seafarers for operational error | 0.701 | |||

| D8.3 Small crew size onboard | 0.508 | 0.514 | 0.772 | |

| D8.4 Too much paperwork to be done per voyage | 0.727 | |||

| D8.5 Loneliness while at sea | 0.732 | 0.671 | ||

| D8.7 Onboard fatigue | 0.560 | 0.516 | 0.824 | |

| D8.9 Lack of adequate rest | 0.583 | 0.521 | 0.729 | |

| D8.10 Staying long time at sea away from family | 0.672 | 0.529 | ||

| D8.11 Too much workload onboard | 0.509 | 0.841 | ||

| D8.14 Availability of job opportunities on land | 0.532 | 0.626 | ||

| D6.1 To live in a relationship | 0.777 | |||

| D6.2 Desire to start a family | 0.812 | |||

| D6.3 To care for aging parents | 0.778 | |||

| D6.4 Family stress | 0.734 | |||

| D6.5 Financial stress | 0.758 | |||

| D6.7 Desire to work on land | 0.671 | 0.504 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caesar, L.D. Emerging Dynamics of Training, Recruiting and Retaining a Sustainable Maritime Workforce: A Skill Resilience Framework. Sustainability 2024, 16, 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010239

Caesar LD. Emerging Dynamics of Training, Recruiting and Retaining a Sustainable Maritime Workforce: A Skill Resilience Framework. Sustainability. 2024; 16(1):239. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010239

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaesar, Livingstone Divine. 2024. "Emerging Dynamics of Training, Recruiting and Retaining a Sustainable Maritime Workforce: A Skill Resilience Framework" Sustainability 16, no. 1: 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010239

APA StyleCaesar, L. D. (2024). Emerging Dynamics of Training, Recruiting and Retaining a Sustainable Maritime Workforce: A Skill Resilience Framework. Sustainability, 16(1), 239. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16010239