Effects of Individualism, Collectivism, Materialism, and Willingness to Pay for Environmental Protection on Environmental Consciousness and Pro-Environmental Consumption Behavior in Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Environmental Consciousness

2.2.2. Individualism and Collectivism

2.2.3. Materialism

2.2.4. WTP for Environmental Protection

2.2.5. Pro-Environmental Consumption Behavior

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Clusters

3.2. Differences between Individualism, Collectivism, Materialism, WTP for Environmental Protection, and Environmental Consciousness between Groups with Low and High Environmental Consciousness

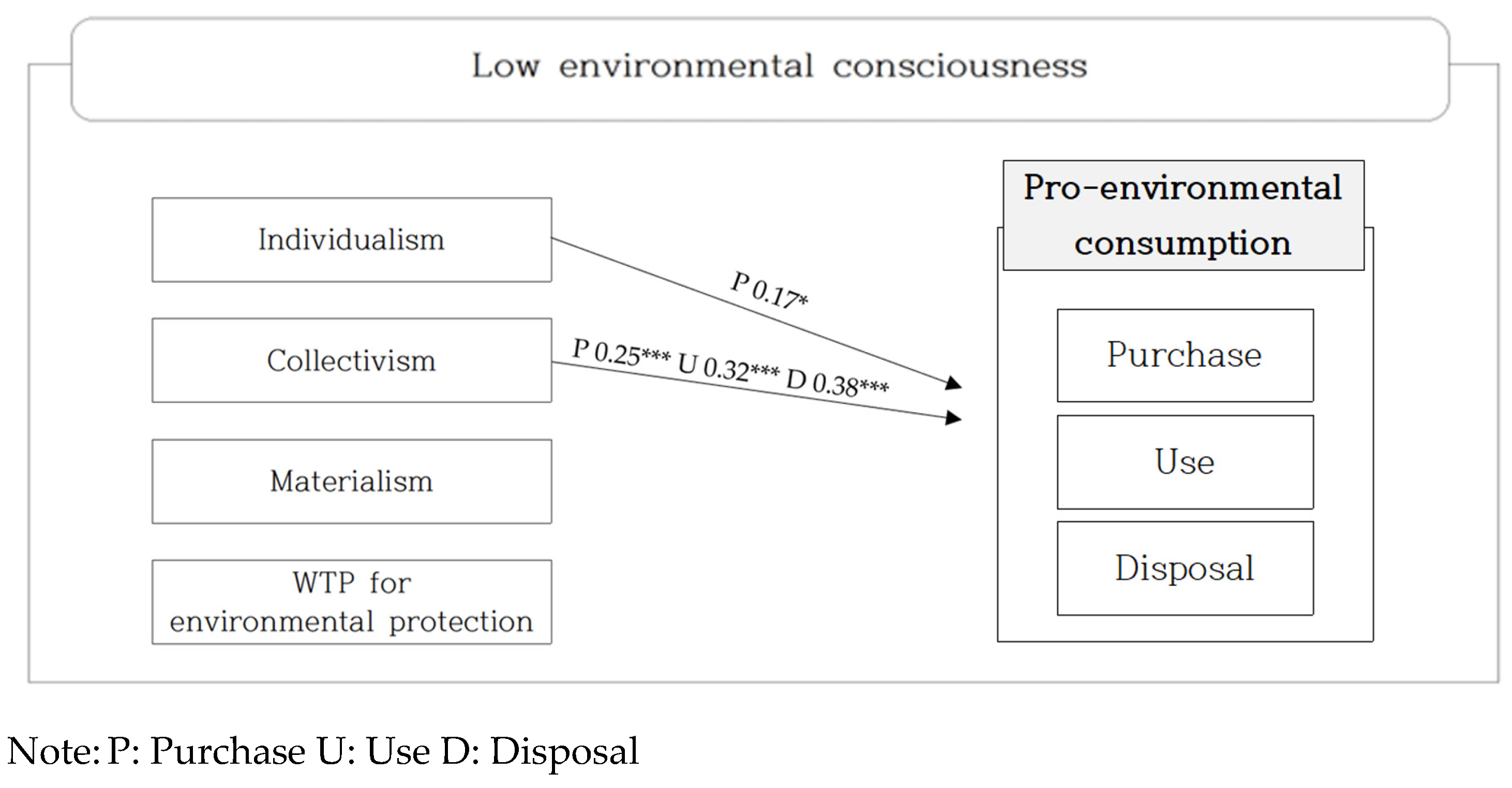

3.3. Factors Affecting Pro-Environmental Consumption Behavior in the Low Environmental Consciousness Group

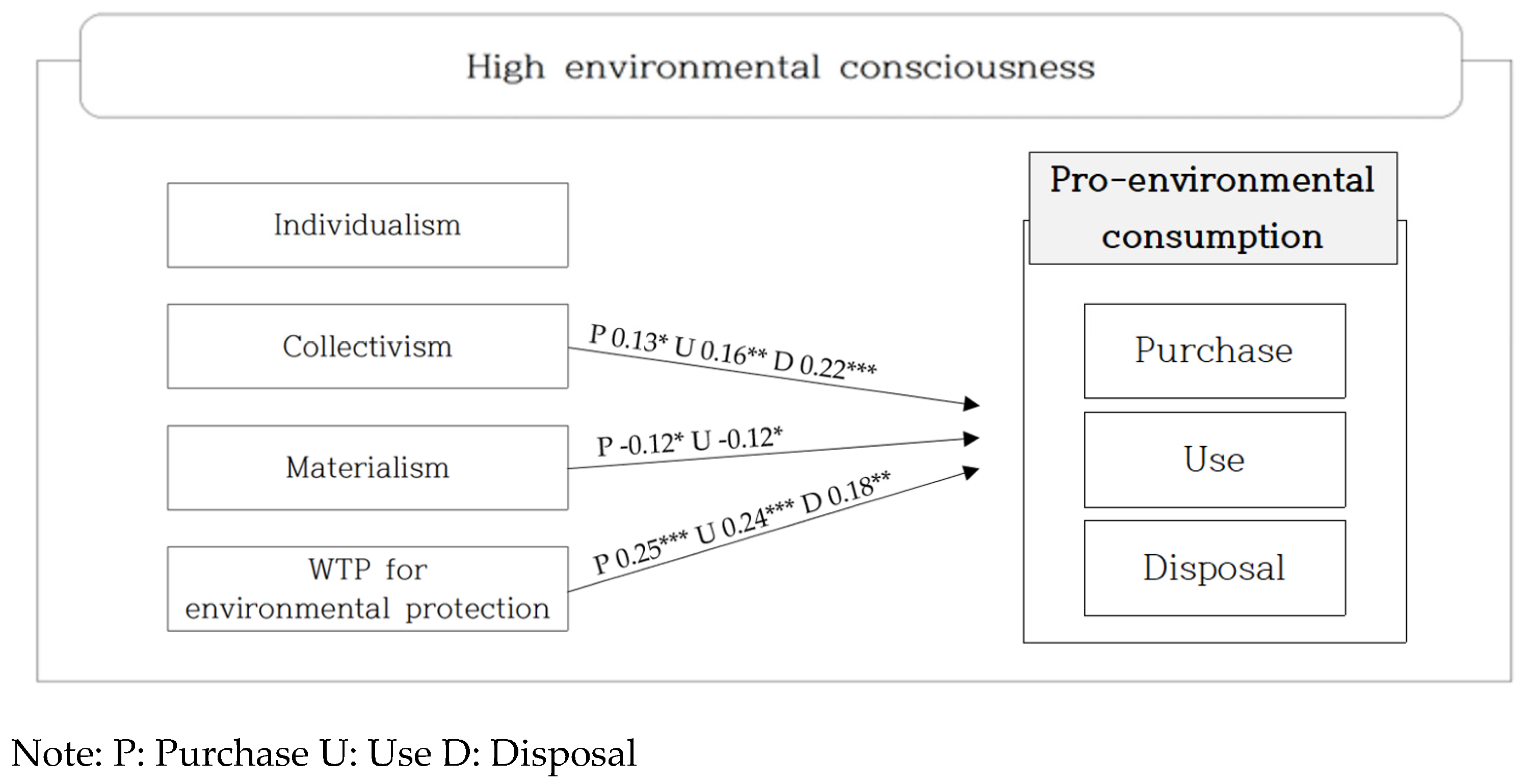

3.4. Factors Affecting Pro-Environmental Consumption Behavior in the Group with High Environmental Consciousness

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions and Limitations

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Economic Forum. The Global Risks Report 2021 16th Edition. World Economic Forum. 2001. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-risks-report-2021 (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Seo, Y.L. Domestic. Waste Increased Due to COVID-19. Small Action. In My Hand Seoul News. Available online: https://mediahub.seoul.go.kr/archives/2000966 (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Statistics Korea. Korean Social Trends. 2020. Available online: http://kostat.go.kr/sri/srikor/srikor_pbl/7/2/index.board?bmode=read&bSeq=&aSeq=386936&pageNo=1&rowNum=10&navCount=10&currPg=&searchInfo=&sTarget=title&sTxt= (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Kye, S.J. Study on children’s consciousness and behavior for the environmental conservation. Hum. Ecol. Res. 1997, 35, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Alibei, M.A.; Johnson, C. Environmental concern: A cross-cultural analysis. J. Int. Cross-Cult. Stud. 2009, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Samdahl, D.M.; Robertson, R. Social determinants of environmental concern: Specification and test of the model. Environ. Behav. 1989, 21, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, M.R.; Stafford, T.F.; Stafford, M.R. Green issues: Dimensions of environmental concern. J. Bus. Res. 1994, 31, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd’Razack, N.T.; Medayese, S.O.; Shaibu, S.I.; Adeleye, B.M. Habits and benefits of recycling solid waste among households in Kaduna, North West Nigeria. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 28, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.H.; Kim, K.J.; Rha, J.Y.; Choi, S.A. Green consumption competency: A conceptual model of its framework and components. Consum. Policy Educ. Rev. 2010, 6, 95–119. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, P.W.; Gouveia, V.V.; Cameron, L.D.; Tankha, G.; Schmuck, P.; Fraěk, M. Values and their relationship to environmental concern and conservation behavior. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2005, 36, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Roth, K. Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.J.; Lee, J.S.; Sheu, C. Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.C.; Lin, T.H.; Lai, M.C.; Lin, T.L. Environmental consciousness and green customer behavior: An examination of motivation crowding effect. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.T.; Niu, H.J. Green consumption: Environmental knowledge, environmental consciousness, social norms, and purchasing behavior. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1679–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Cho, S.Y. The effects of high school students’ environmental concerns and subjective norms on purchase intentions of eco-friendly products: Mediating effect of attitude toward eco-friendly products and service. J. Korean Soc. Environ. Educ. 2019, 32, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birgelen, M.; Semeijn, J.; Keicher, M. Packaging and pro-environmental consumption behavior—Investigating purchase and disposal decisions for beverages. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C.; Gelfand, M.J. Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.E.M.; Geyskens, I. How country characteristics affect the perceived value of websites. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, D.; Hahn, R. Understanding collaborative consumption: An extension of the theory of planned behavior with value-based personal norms. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 158, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. Individualism and Collectivism; Westview Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-081-331-850-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hooft, E.V.; Jong, M. Predicting job seeking for temporary employment using the theory of planned behavior: The moderating role of individualism and collectivism. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iran, S.; Geiger, S.M.; Schrader, U. Collaborative fashion consumption–a cross cultural study between Tehran and Berlin. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J.A.; Shrum, L.J. The influence of individualism, collectivism, and locus of control on environmental beliefs and behavior. J. Public Policy Mark. 2001, 20, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.K. Determinants of Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2001, 18, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Y. Effect of collectivist orientation and ecological attitude on actual environmental commitment: The moderating role of consumer demographics and product involvement. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 1997, 9, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Aswal, C. Green purchase intentions, collectivism and materialism: An empirical investigation. Delhi Univ. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2017, 4, 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.M. Antecedents of green purchase behavior: An examination of collectivism, environmental concern, and Pce. Adv. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 592–599. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, R.W. Materialism: Trait aspects of living in the material world. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, J. Shop ‘til we drop? Television, materialism and attitudes about the natural environment. Mass Commun. Soc. 2007, 10, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilikidou, I.; Delistavrou, A. Influence of the Materialistic Values on Consumers’ Pro-environmental Post-purchase Behavior. In Marketing Theory and Applications, Proceedings of the 2004 American Marketing Association Winter Educators’ Conference 15; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2004; pp. 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Strizhakova, Y.; Coulter, R.A. The ‘green’ side of materialism in emerging BRIC and developed markets: The moderating role of global cultural identity. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2013, 30, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleim, M.R.; Smith, J.S.; Andrews, D.; Cronin, J.J., Jr. Against the green: A multi-method examination of the barriers to green consumption. J. Retail. 2013, 89, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Rana, J. Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Zamora, M.; Torres-Ruiz, F.J.; Murgado-Armenteros, E.M.; Parras-Rosa, M. Organic as a heuristic cue: What Spanish consumers mean by organic foods. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, V.A.; Karakaya, F. Consumer segments in organic foods market. J. Consum. Mark. 2014, 31, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essoussi, L.H.; Zahaf, M. Decision making process of community organic food consumers: An exploratory study. J. Consum. Mark. 2008, 25, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grankvist, G.; Biel, A. The importance of belief and purchase criteria in the choice of eco-labeled food products. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C.; Kast, S.W. Promoting sustainable consumption: Determinants of green purchases by Swiss consumers. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 883–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organic Consumers Association. Despite the Economic Dip, Organic Food Sales Soar. Despite Economic Dip, Organic Food Sales Soar. Available online: https://www.organicconsumers.org (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Kang, K.H.; Stein, L.; Heo, C.Y.; Lee, S. Consumers’ willingness to pay for green initiatives of the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, E.L. It’s not easy being green: The effects of attribute tradeoffs on green product preference and choice. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 41, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J.A.; Shrum, L.J. The recycling of solid wastes: Personal values, value orientations, and attitudes about recycling as antecedents of recycling behavior. J. Bus. Res. 1994, 30, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.B. Influence on the Product Image and Product Purchasing-Intention of Environmental Consciousness of Consumers. Master’s Thesis, Dong-A University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.H. Study on Lifestyle Characteristics, Environmental Consciousness and Consumption Behavior of Green Consumers. Master’s Thesis, Ewha womans University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, W.A.; Kim, K.O. Scale development in the propensity of collectivism—Individualism among Korean consumers. J. Consum. Stud. 2000, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yim, M.J. The Effects of Face Circumstances upon Consumption Behavior Intention: Focusing on the Moderating Effect of Materialism and Individualism. Ph.D. Thesis, Dong-A University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- You, J.H.; Seoul, K.O.A. Validation study of the Korean version of material values scale. Korean J. Cult. Soc. Issues 2018, 24, 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Moon, H.; Jung, S.E.; Severt, K. The effect of environmental values and attitudes on consumer willingness to pay more for organic menus: A value-attitude-behavior approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 33, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.C.; Kim, C.S.; Lee, C.H. The level of corporate social responsibility’s effects on public favorability and willingness to pay the premium price. Korean J. Advert. 2009, 20, 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, E.A.; Lee, K.A. A Study on Green Consumption Capacity Assessment; Korea Consumer Agency: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Soyer, M.; Dittrich, K. Sustainable consumer behavior in purchasing, using and disposing of clothes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice-Hall: Bergen County, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0138132637. [Google Scholar]

- Arısal, I.; Atalar, T. The exploring relationships between environmental concern, collectivism and ecological purchase intention. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 235, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Park, N.K.; Han, J.H. Gender difference in environmental attitude and behaviors in adoption of energy-efficient lighting at home. J. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 6, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L.M.; Hatch, A.; Johnson, A. Cross-national gender variation in environmental behaviors. Soc. Sci. Q. 2004, 85, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thormann, T.F.; Wicker, P. Willingness-to-pay for environmental measures in non-profit sport clubs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusyani, E.; Lavuri, R.; Gunardi, A. Purchasing eco-sustainable products: Interrelationship between environmental knowledge, environmental concern, green attitude, and perceived behavior. Sustainability 2001, 13, 4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booysen, F.; Guvuriro, S.; Campher, C. Horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism and preferences for altruism: A social discounting study. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 178, 110856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.K. Thinking green, buying green? Drivers of pro-environmental purchasing behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2015, 32, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H’Mida, S. Factors contributing in the formation of consumers’ environmental consciousness and shaping green purchasing decisions. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Computers & Industrial Engineering, Troyes, France, 6–9 July 2009; pp. 957–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.H.; Hahn, J.H. Green consumers’ self-construal and commitment with the impact of environmental education. J. Vocat. Educ. Res. 2009, 28, 133–156. [Google Scholar]

- Tilikidou, I. The effects of knowledge and attitudes upon Greeks’ pro-environmental purchasing behavior. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2007, 14, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, W.; Yongquan, H. Effect of materialism on pro-environmental behavior among youth in China: The role of nature connectedness. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Information, incentives, and pro-environmental consumer behavior. J. Consum. Policy 1999, 22, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Characteristics | S.D./% | Mean/n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 50.00 | 236 |

| Male | 50.00 | 236 | |

| Education | ≤High school graduate | 21.19 | 100 |

| University graduate | 68.21 | 322 | |

| >University graduate | 10.59 | 50 | |

| Income (Units: Monthly; €1 = ₩1450) | Under €1400 | 11.23 | 153 |

| €1400 to less than €2100 | 19.92 | 94 | |

| €2100 to less than €2800 | 18.64 | 88 | |

| €2800 to less than €3500 | 13.98 | 66 | |

| €3500 to less than €4200 | 13.14 | 62 | |

| €4200 to less than €4900 | 9.32 | 44 | |

| €4900 to less than €5600 | 4.66 | 22 | |

| €5600 to less than €6300 | 4.45 | 21 | |

| €6300 to less than €7000 | 2.12 | 10 | |

| Over €7000 | 2.54 | 12 | |

| Age (years) | 13.31 | 44.33 |

| Total | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | t-Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 472 (100.00) | 212 (44.92) | 260 (55.08) | |

| M (S.D) | M (S.D) | M (S.D) | ||

| Environmental consciousness | 4.34 (0.49) | 3.89 (0.35) | 4.70 (0.20) | −31.36 *** |

| Low Environmental Consciousness (n = 212) | High Environmental Consciousness (n = 260) | t-Statistic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | S.D. | M | S.D. | |||

| Individualism | 3.34 | 0.49 | 3.32 | 0.63 | 0.44 | |

| Collectivism | 3.57 | 0.48 | 3.79 | 0.59 | −4.31 *** | |

| Materialism | 2.92 | 0.49 | 2.74 | 0.53 | 3.65 *** | |

| WTP for environmental protection | 3.27 | 0.75 | 4.03 | 0.77 | −10.82 *** | |

| Pro-environmental consumption behavior | Purchase | 3.52 | 0.54 | 3.96 | 0.57 | −8.49 *** |

| Use | 3.50 | 0.52 | 3.96 | 0.57 | −9.03 *** | |

| disposal | 3.62 | 0.55 | 3.93 | 0.62 | −5.61 *** | |

| Pro-Environmental Consumption Behavior | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchase | Use | Disposal | ||||||||

| B | β | SE | B | β | SE | B | β | SE | ||

| (constant) | 0.98 | 0.46 | 1.55 | 0.41 | 1.38 | 0.47 | ||||

| Control variable | Gender (ref. Female) | |||||||||

| Male | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.07 | −0.12 | −0.12 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 | |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.01 ** | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | |

| Education level (ref ≤High school graduate) | ||||||||||

| University graduate | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.12 | |

| >University graduate | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.26 * | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.14 | |

| Income | −0.03 * | −0.14 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.02 | |

| Independent variable | Individualism | 0.19 * | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| Collectivism | 0.28 *** | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.35 *** | 0.32 | 0.07 | 0.44 *** | 0.38 | 0.08 | |

| Materialism | −0.13 | −0.12 | 0.08 | −0.07 | −0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.08 | |

| WTP for environmental protection | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | |

| F(9, 202) | 5.26 *** | 9.14 *** | 5.18 *** | |||||||

| R2 | 0.190 | 0.290 | 0.188 | |||||||

| Adj.R2 | 0.154 | 0.258 | 0.152 | |||||||

| Pro-Environmental Consumption Behavior | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchase | Use | Disposal | ||||||||

| B | β | SE | B | β | SE | B | β | SE | ||

| (constant) | 2.90 | 0.43 | 2.82 | 0.42 | 2.89 | 0.47 | ||||

| Control variable | Gender (ref. Female) | |||||||||

| Male | −0.06 | −0.05 | 0.07 | −0.15 * | −0.13 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.08 | |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.12 | 0.00 | |

| Education level (ref ≤High school graduate) | ||||||||||

| University graduate | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.12 | |

| >University graduate | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.14 | |

| Income | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| Independent variable | Individualism | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.06 |

| Collectivism | 0.13 * | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.15 ** | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.23 *** | 0.22 | 0.07 | |

| Materialism | −0.13 * | −0.12 | 0.07 | −0.13 * | −0.12 | 0.06 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.07 | |

| WTP for environmental protection | 0.19 *** | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.18 *** | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.14 ** | 0.18 | 0.05 | |

| F(9, 205) | 3.96 *** | 4.61 *** | 3.26 ** | |||||||

| R2 | 0.125 | 0.142 | 0.105 | |||||||

| Adj.R2 | 0.093 | 0.112 | 0.073 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cho, S.Y.; Jung, J. Effects of Individualism, Collectivism, Materialism, and Willingness to Pay for Environmental Protection on Environmental Consciousness and Pro-Environmental Consumption Behavior in Korea. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7596. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097596

Cho SY, Jung J. Effects of Individualism, Collectivism, Materialism, and Willingness to Pay for Environmental Protection on Environmental Consciousness and Pro-Environmental Consumption Behavior in Korea. Sustainability. 2023; 15(9):7596. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097596

Chicago/Turabian StyleCho, So Yeon, and Joowon Jung. 2023. "Effects of Individualism, Collectivism, Materialism, and Willingness to Pay for Environmental Protection on Environmental Consciousness and Pro-Environmental Consumption Behavior in Korea" Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7596. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097596

APA StyleCho, S. Y., & Jung, J. (2023). Effects of Individualism, Collectivism, Materialism, and Willingness to Pay for Environmental Protection on Environmental Consciousness and Pro-Environmental Consumption Behavior in Korea. Sustainability, 15(9), 7596. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097596