Integrating OCBE Literature and Norm Activation Theory: A Moderated Mediation on Proenvironmental Behavior of Employees

Abstract

1. Introduction

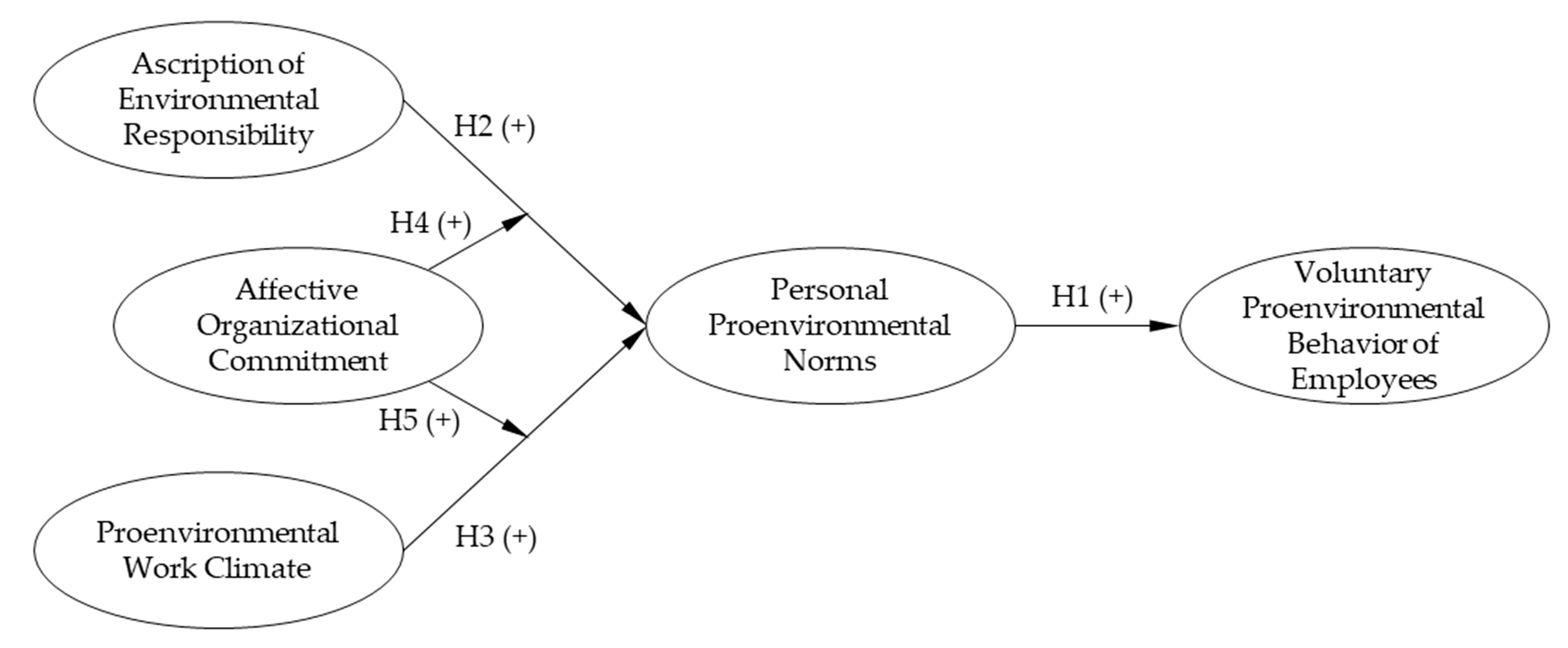

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Conceptualizing Voluntary Proenvironmental Behavior

2.2. VPBE and the Case of Student Workforce

2.3. Determinants of VPBE

2.3.1. Determinants of VPBE from the Norm Activation Model

2.3.2. Determinants of VPBE from an OCBE Perspective

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Participants

3.2. Measurements, Data Preparation, and Analyses

| Common Domains | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author(s) (Chronological) | Scale | Resource Conservation | Mobility Behavior | Environmentally Sound Consumption | Recycling and Waste Avoidance | Further Domains |

| Schultz and Zelezny [193] | Self-reported proenvironmental behaviors across cultures | Conserve water Conserve energy | Public transportation | Purchase environmentally safe products | Recycling | |

| Kaiser and Wilson [194] | General ecological behavior | Water and power conservation | Ecological automobile use | Ecologically aware consumer behavior | Ecological garbage removal Garbage inhibition | Prosocial behavior Volunteering in nature-protection activities |

| Nordlund and Garvill [98] | Domains of everyday proenvironmental behaviors | Energy conservation | Transportation behavior | Environmentally responsible consumption | Recycling and reusing | |

| Kaiser et al. [195] | Forty behavior items grouped into six domains | Energy conservation | Mobility and transportation | Consumerism | Waste avoidance Recycling | Vicarious behaviors toward conservation |

| Whitmarsh and O’Neill [182] | Proenvironmental behavior | Energy and water use | Transport actions | Environmentally sound shopping choices | Waste behavior | |

| Swim and Becker [196] | Environmentally friendly behavior | Energy conservation | Change in food consumption | Activism for climate change | ||

| Lanzini and Thøgersen [197] | Self-reported proenvironmental behaviors | Energy and water conservation | Public transport Biking Carpooling | Green purchasing | Recycling Saving paper | Volunteering |

| López-Mosquera et al. [198] | Habitual proenvironmental behaviors | Reduced car use frequency | Environmentally responsible purchase frequency | Recycling frequency | ||

| Rhead et al. [199] | Proenvironmental behavior categories | Water and energy conservation | Travel | Food | Recycling | |

| Larson et al. [38] | Frequently studied universal actions of environmentalism and civic engagement | Water conservation Energy conservation | Environmentally conscious transportation | Green or ecofriendly purchasing | Recycling Waste reduction | Proenvironmental actions in the socio-political arena |

| Balundė et al. [200] | General ecological behavior | Fuel-efficient driving | Sustainable transportation modes | Recycling behavior | Environmental activism | |

| Li et al. [53] | Review article; no single scale but categories | Energy consumption | Transport use | Purchase of green products | Recycling Waste management | |

| Yuriev et al. [201] | Review article; no single scale but categories | Energy-saving | Traveling and commuting | Recycling | General green behaviors Other | |

| Foster et al. [52] | Proenvironmental behavior categories | Air-conditioning Printing Drinking (to capture energy and water conservation) Computer use Light use | Sustainable shopping | Recycling | ||

| Construct | α | KMO | MSA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | ||||

| Ascription of environmental responsibility (AER) | 0.73 | 0.71 | ||

| I feel jointly responsible for environmental pollution, losses of biodiversity, and global warming because of … | ||||

| … my consumption of resources (e.g., energy and water). (AER_01) | 0.68 | |||

| … my mobility behavior. (AER_02) | 0.74 | |||

| … my food consumption (e.g., meat consumption). (AER_03) | 0.77 | |||

| … the waste I generate. (AER_04) | 0.69 | |||

| Proenvironmental work climate (PEWC) | 0.92 | 0.89 | ||

| Our organization believes it is important to protect the environment. (PEWC_01) | 0.91 | |||

| The goals of our organization are directly aligned with environmental issues and concerns. (PEWC_02) | 0.91 | |||

| In our organization, employees try to minimize harm to the environment. (PEWC_03) | 0.89 | |||

| In our organization, employees care about the environment. (PEWC_04) | 0.91 | |||

| Our organization’s environmental efforts receive full support from our senior management. (PEWC_05) | 0.87 | |||

| Our organization’s environmental goals are driven by the senior management team. (PEWC_06) | 0.87 | |||

| Affective organizational commitment (AC) | 0.88 | 0.71 | ||

| Working for my organization has a great deal of personal meaning to me. (AC_01) | 0.78 | |||

| I feel a strong sense of belonging to my organization. (AC_02) | 0.65 | |||

| I feel emotionally attached to my organization. (AC_03) | 0.72 | |||

| Personal proenvironmental norms (PEN) | 0.78 | 0.76 | ||

| I feel a personal obligation to … | ||||

| … fulfill my tasks at the workplace as resource-conserving as possible (e.g., saving energy and water). (PEN_01) | 0.73 | |||

| … be mobile as environmentally friendly as possible during my work (e.g., travel to work, business travels, short distances). (PEN_02) | 0.76 | |||

| … to buy or consume environmentally friendly produce at the workplace (e.g., seasonal produce, locally grown, and organic foods). (PEN_03) | 0.79 | |||

| … produce as little waste as possible at my workplace, and recycle paper, beverage bottles, etc. (PEN_04) | 0.76 | |||

| Voluntary proenvironmental behavior (VPBE) | 0.81 | 0.79 | ||

| I take every opportunity to actively participate in environmental protection at work. (VPBE_01) | 0.82 | |||

| I do more for the environment at work than I am expected to. (VPBE_02) | 0.75 | |||

| I try to convince my colleagues of the importance of protecting the environment. (VPBE_03) | 0.79 | |||

| I make suggestions about environmentally friendly practices to my supervisors, in an effort to increase my company’s environmental performance. (VPBE_04) | 0.82 | |||

| I point out to my colleagues their non-ecological behavior. (VPBE_05) | 0.77 | |||

4. Results

| No. | Measure | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AER | 3.26 | 0.80 | — | |||||||

| 2 | PEWC | 3.15 | 0.93 | 0.06 | — | ||||||

| 3 | AC | 3.24 | 0.90 | 0.16 ** | 0.25 ** | — | |||||

| 4 | PEN | 3.69 | 0.70 | 0.29 ** | 0.15 * | 0.08 | — | ||||

| 5 | VPBE | 2.57 | 0.78 | 0.19 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.14 | 0.48 ** | — | |||

| 6 | Age | 24.12 | 2.42 | –0.00 | 0.12 | 0.14 | –0.01 | 0.12 | — | ||

| 7 | Sex (1 = female) | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0.01 | –0.05 | 0.03 | 0.25 ** | –0.08 | –0.21 ** | — | |

| 8 | Graduate (1 = master) | 0.65 | 0.48 | –0.04 | 0.11 | 0.18 * | –0.05 | –0.04 | 0.48 ** | 0.04 | — |

| Model 1 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: Personal proenvironmental norms | Estimate | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |||

| Constant | 3.66 | 0.05 | 73.38 | 0.00 | 3.56 | 3.76 | |||

| Independent variables | |||||||||

| Proenvironmental work climate | 0.10 | 0.05 | 1.97 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.19 | |||

| Ascription of responsibility | 0.21 | 0.05 | 4.09 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.30 | |||

| Moderator | |||||||||

| Affective organizational commitment | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.82 | –0.09 | 0.11 | |||

| Interactions | |||||||||

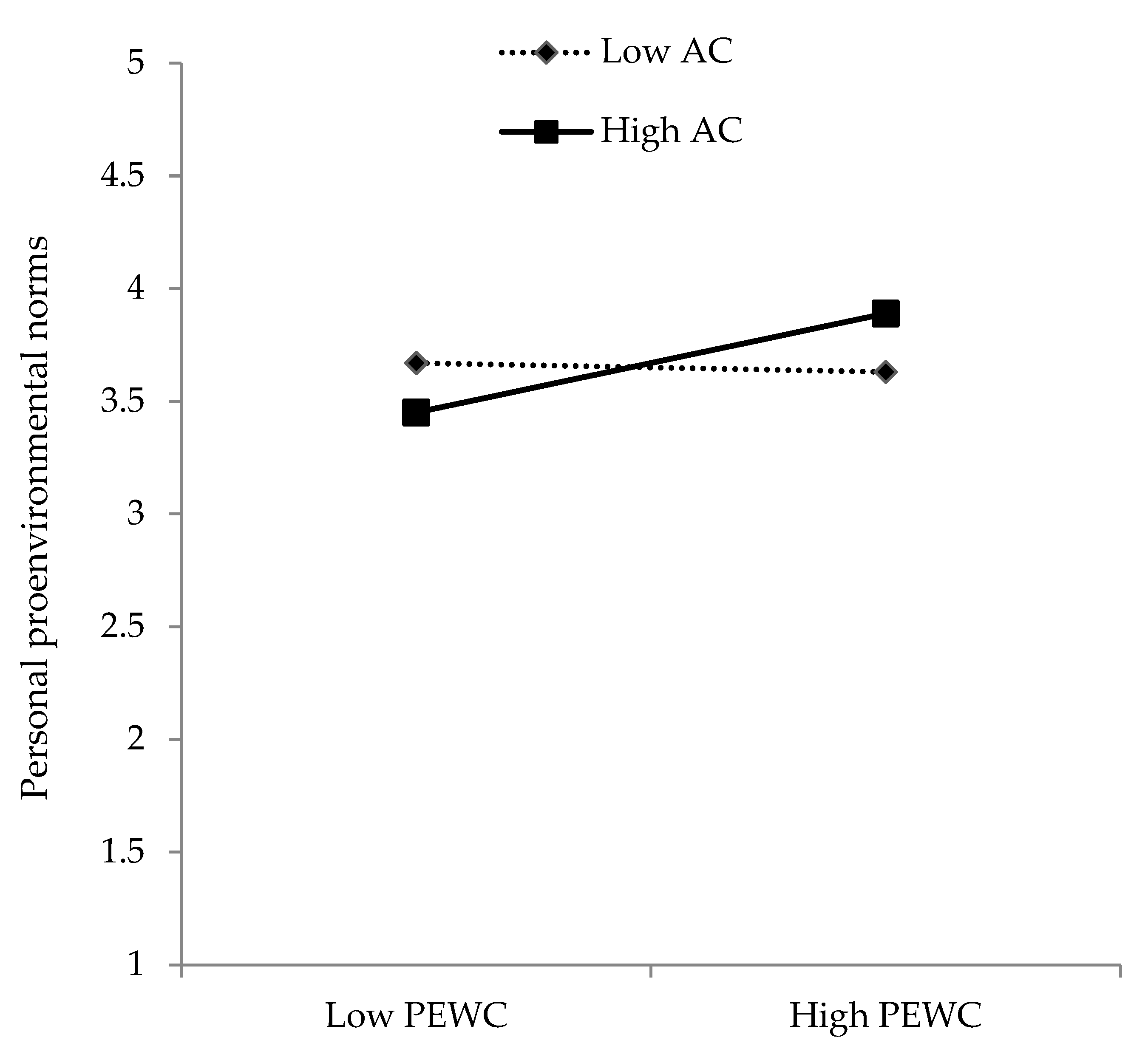

| Affective organizational commitment x Proenvironmental work climate | 0.12 | 0.04 | 2.78 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.21 | |||

| Affective organizational commitment x Ascription of responsibility | –0.03 | 0.05 | –0.49 | 0.62 | –0.13 | 0.08 | |||

| R2 | 0.14 | ||||||||

| F(5,183) | 6.04 *** | ||||||||

| Model 2 | |||||||||

| Dependent variable: Voluntary proenvironmental behavior of employees | Estimate | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |||

| Constant | 0.77 | 0.28 | 2.77 | 0.01 | 0.22 | 1.32 | |||

| Independent variables | |||||||||

| Proenvironmental work climate | 0.10 | 0.05 | 2.10 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.20 | |||

| Ascription of responsibility | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.76 | 0.45 | –0.06 | 0.14 | |||

| Mediator | |||||||||

| Personal proenvironmental norms | 0.49 | 0.07 | 6.57 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.63 | |||

| R2 | 0.25 | ||||||||

| F(3,185) | 20.41 *** | ||||||||

5. Discussion

5.1. Normative Mechanisms Underlying VPBE: Distinguishing Integrated and Introjected Proenvironmental Norms

5.2. Theoretical Implications for the Application of the Norm Activation Model to the Corporate Context for Proenvironmental Behavior

5.3. Implications for Practice

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5.5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Babiak, K.; Trendafilova, S. CSR and environmental responsibility: Motives and pressures to adopt green management practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 18, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, A.; de Gregorio, E.; Bonnes, M.; Bonaiuto, M.; Carrus, G.; Garcia-Mira, R.; Maricchiolo, F. Low carbon energy behaviors in the workplace: A qualitative study in Italy and Spain. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lülfs, R.; Hahn, R. Corporate Greening beyond Formal Programs, Initiatives, and Systems: A Conceptual Model for Voluntary Pro-environmental Behavior of Employees. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2013, 10, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravind, D.; Christmann, P. Decoupling of Standard Implementation from Certification: Does Quality of ISO 14001 Implementation Affect Facilities’ Environmental Performance? Bus. Ethics Q. 2011, 21, 73–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Ahmad, N.; Sial, M.S.; Cherian, J.; Han, H. CSR and organizational performance: The role of pro-environmental behavior and personal values. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 30, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. The relationship between pro-environmental attitude and employee green behavior: The role of motivational states and green work climate perceptions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2020, 27, 7341–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Environmental Sustainability at Work: A Call to Action. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 5, 444–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Kim, Y.; Han, K.; Jackson, S.E.; Ployhart, R.E. Multilevel Influences on Voluntary Workplace Green Behavior: Individual Differences, Leader Behavior, and Coworker Advocacy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1335–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruepert, A.M.; Keizer, K.; Steg, L. The relationship between Corporate Environmental Responsibility, employees’ biospheric values and pro-environmental behaviour at work. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, I.M.; Rauvola, R.S.; Rudolph, C.W.; Zacher, H. Employee green behavior: A meta-analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1146–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; Arshad, M.Z.; Kamran, H.w.; Scholz, M.; Han, H. Relationship between corporate social responsibility at the micro-level and environmental performance: The mediating role of employee pro-environmental behavior and the moderating role of gender. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuriev, A.; Boiral, O.; Francoeur, V.; Paillé, P. Overcoming the barriers to pro-environmental behaviors in the workplace: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Umrani, W.A. Corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behavior at workplace: The role of moral reflectiveness, coworker advocacy, and environmental commitment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Farrukh, M.; Iqbal, M.K.; Farhan, M.; Wu, Y. Corporate social responsibility and employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior: The role of organizational pride and employee engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1104–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Toward a new measure of organizational environmental citizenship behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 75, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtz, G.M.; Williams, K.J. Attitudinal and motivational antecedents of participation in voluntary employee development activities. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 635–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.E.; Ulhas, K.R. Working to Reduce Food Waste: Investigating Determinants of Food Waste amongst Taiwanese Workers in Factory Cafeteria Settings. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Paillé, P. Organizational Citizenship Behaviour for the Environment: Measurement and Validation. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Chen, Y.; Boiral, O.; Jin, J. The Impact of Human Resource Management on Environmental Performance: An Employee-Level Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Mejía-Morelos, J.H.; Marché-Paillé, A.; Chen, C.C.; Chen, Y. Corporate Greening, Exchange Process among Co-workers, and Ethics of Care: An Empirical Study on the Determinants of Pro-Environmental Behaviors at Coworkers-Level. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raineri, N.; Mejía-Morelos, J.H.; Francoeur, V.; Paillé, P. Employee eco-initiatives and the workplace social exchange network. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordano, M.; Welcomer, S.; Scherer, R.F.; Pradenas, L.; Parada, V. A Cross-Cultural Assessment of Three Theories of Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Comparison between Business Students of Chile and the United States. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 634–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. The norm activation model and theory-broadening: Individuals’ decision-making on environmentally-responsible convention attendance. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, G. Antecedents of employee electricity saving behavior in organizations: An empirical study based on norm activation model. Energy Policy 2013, 62, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.; Shivarajan, S.; Blau, G. Enacting Ecological Sustainability in the MNC: A Test of an Adapted Value-Belief-Norm Framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 59, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannakis, G.; Lioukas, S. Values, attitudes and perceptions of managers as predictors of corporate environmental responsiveness. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 100, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherbaum, C.A.; Popovich, P.M.; Finlinson, S. Exploring Individual-Level Factors Related to Employee Energy-Conservation Behaviors at Work. J. Appl. Soc. Pyschol. 2008, 38, 818–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Mejía-Morelos, J.H. Modelling How Managers Support Their Subordinates toward Environmental Sustainability: A Moderated-Mediation Study. JABR 2017, 33, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesenheimer, J.S.; Greitemeyer, T. Special Issue “What Influences an Individual’s Pro-environmental Behavior?” Sustainability 2021. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability/special_issues/individual_pro_environmental_behavior (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Thøgersen, J. Norms for environmentally responsible behaviour: An extended taxonomy. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Howard, J.A. A normative decision-making model of altruism. In Altruism and Helping Behavior; Rushton, J.P., Sorrentino, R.M., Eds.; L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 1981; pp. 89–211. [Google Scholar]

- Temminck, E.; Mearns, K.; Fruhen, L. Motivating Employees towards Sustainable Behaviour. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2015, 24, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosti-Kharas, J.; Lamm, E.; Thomas, T.E. Organization OR Environment? Disentangling Employees’ Rationales behind Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment. Organ. Environ. 2017, 30, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Sarigöllü, E. The Behavior-Attitude Relationship and Satisfaction in Proenvironmental Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 1106–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.R.; Stedman, R.C.; Cooper, C.B.; Decker, D.J. Understanding the multi-dimensional structure of pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Dewitte, S. Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 63, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blok, V.; Wesselink, R.; Studynka, O.; Kemp, R. Encouraging sustainability in the workplace: A survey on the pro-environmental behaviour of university employees. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Poškus, M.S. The Importance of Environmental Knowledge for Private and Public Sphere Pro-Environmental Behavior: Modifying the Value-Belief-Norm Theory. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, A.; Maleksaeidi, H. Pro-environmental behavior of university students: Application of protection motivation theory. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Boiral, O. Pro-environmental behavior at work: Construct validity and determinants. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruepert, A.M.; Keizer, K.; Steg, L.; Maricchiolo, F.; Carrus, G.; Dumitru, A.; García Mira, R.; Stancu, A.; Moza, D. Environmental considerations in the organizational context: A pathway to pro-environmental behaviour at work. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 17, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.H.; Peters, G.-J.Y.; Kok, G. A Review of Determinants of and Interventions for Proenvironmental Behaviors in Organizations. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 2933–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, T.L.; Barr, S.W.; Gilg, A.W. A Novel Conceptual Framework for Examining Environmental Behavior in Large Organizations: A Case Study of the Cornwall National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 426–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratt, C.; Stern, P.C.; Matthies, E.; Nenseth, V. Home, Car Use, and Vacation. Environ. Behav. 2014, 47, 436–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamm, E.; Tosti-Kharas, J.; Williams, E.G. Read This Article, but Don’t Print It: Organizational Citizenship Behavior toward the Environment. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 163–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.H.; Peters, G.-J.Y.; Kok, G. Energy-Related Behaviors in Office Buildings: A Qualitative Study on Individual and Organisational Determinants. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 61, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, B.; Muhammad, Z.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Faezah, J.N.; Johansyah, M.D.; Yong, J.Y.; ul-Haque, A.; Saputra, J.; Ramayah, T.; Fawehinmi, O. Determinants of Pro-Environmental Behaviour in the Workplace. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhao, L.; Ma, S.; Shao, S.; Zhang, L. What influences an individual’s pro-environmental behavior? A literature review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Employee Green Behaviors. In Managing Human Resources for Environmental Sustainability; Jackson, S.E., Ones, D.S., Dilchert, S., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 85–116. ISBN 978-0-470-88720-2. [Google Scholar]

- Boiral, O.; Paillé, P.; Raineri, N. The Nature of Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors. In The Psychology of Green Organizations; Robertson, J.L., Barling, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 12–32. ISBN 9780199997480. [Google Scholar]

- Zientara, P.; Zamojska, A. Green organizational climates and employee pro-environmental behaviour in the hotel industry. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1142–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, B.; Shahzad, K.; Shafi, M.Q.; Paille, P. Predicting required and voluntary employee green behavior using the theory of planned behavior. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1300–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, D.; Rasche, A.; Etzion, D.; Newton, L. Guest Editors’ Introduction: Corporate Sustainability Management and Environmental Ethics. Bus. Ethics Q. 2017, 27, 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tencati, A.; Misani, N.; Castaldo, S. A Qualified Account of Supererogation: Toward a Better Conceptualization of Corporate Social Responsibility. Bus. Ethics Q. 2020, 30, 250–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francoeur, V.; Paillé, P.; Yuriev, A.; Boiral, O. The Measurement of Green Workplace Behaviors: A Systematic Review. Organ. Environ. 2021, 34, 18–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O. Greening the Corporation Through Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gault, J.; Leach, E.; Duey, M. Effects of business internships on job marketability: The employers’ perspective. Educ. Train. 2010, 52, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiman-Smith, L.; Bauer, T.N.; Cable, D.M. Are You Attracted? Do You Intend to Pursue? A Recruiting Policy-Capturing Study. J. Bus. Psychol. 2001, 16, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.N.; Aiman-Smith, L. Green career choices: The influence of ecological stance on recruiting. J. Bus. Psychol. 1996, 10, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, S.; Lucas, R. A coincidence of needs? Empl. Relat. 2001, 23, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant-Smith, D.; McDonald, P. Ubiquitous yet Ambiguous: An Integrative Review of Unpaid Work. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 559–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, P.P. The impact of compensation, supervision and work design on internship efficacy: Implications for educators, employers and prospective interns. J. Educ. Work. 2017, 30, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coco, M. Internships: A Try Before You Buy Arrangement. SAM Adv. Manag. J. 2000, 65, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Knemeyer, A.M.; Murphy, P.R. Logistics internships: Employer and student perspectives. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2002, 32, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divine, R.; Miller, R.; Wilson, J.H.; Linrud, J. Key Philosophical Decisions to Consider When Designing an Internship Program. J. Manag. Mark. Res. 2008, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, P.; Lopes, B.; Costa, M.; Seabra, D.; Melo, A.I.; Brito, E.; Dias, G.P. Stairway to employment? Internships in higher education. High. Educ. 2016, 72, 703–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paisey, C.; Paisey, N.J. Developing skills via work placements in accounting: Student and employer views. Account. Forum 2010, 34, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maertz, C.P., Jr.; Stoeberl, P.A.; Marks, J. Building successful internships: Lessons from the research for interns, schools, and employers. Career Dev. Int. 2014, 19, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.W.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green Human Resource Management: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelly, C.; Cross, J.E.; Franzen, W.S.; Hall, P.; Reeve, S. Reducing Energy Consumption and Creating a Conservation Culture in Organizations: A Case Study of One Public School District. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 316–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J.G. Educating Business Students About Sustainability: A Bibliometric Review of Current Trends and Research Needs. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesselbarth, C.; Schaltegger, S. Educating change agents for sustainability—Learnings from the first sustainability management master of business administration. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Perales, I.; Valero-Gil, J.; La Leyva-de Hiz, D.I.; Rivera-Torres, P.; Garcés-Ayerbe, C. Educating for the future: How higher education in environmental management affects pro-environmental behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, K.-P.; Finstad-Milion, K.; Janczak, S. Educating corporate sustainability—A multidisciplinary and practice-based approach to facilitate students’ learning. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 996–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, A.; Carrico, A.R.; Raimi, K.T.; Truelove, H.B.; Araujo, B.; Yeung, K.L. Meta-analysis of pro-environmental behaviour spillover. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, N.; Franco, M. Antecedents, processes and outcomes of an internship program: An employer’s perspective. JARHE 2022, 14, 556–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magbool, M.A.H.b.; Amran, A.; Nejati, M.; Jayaraman, K. Corporate sustainable business practices and talent attraction. SAMPJ 2016, 7, 539–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoc Thang, N.; Rowley, C.; Mayrhofer, W.; Anh, N.T.P. Generation Z job seekers in Vietnam: CSR-based employer attractiveness and job pursuit intention. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2022, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Story, J.; Castanheira, F.; Hartig, S. Corporate social responsibility and organizational attractiveness: Implications for talent management. Soc. Responsib. J. 2016, 12, 484–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, P.S. The Intern to Employee Career Transition. J. Career Dev. 2018, 45, 566–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, P.S.; Teo, S.T.; Nguyen, D.; Nguyen, N.P. Intern to employee conversion via person–organization fit. Educ. Train. 2021, 63, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewery, D.; Church, D.; Pretti, J.; Nevison, C. Testing a Model of Co-Op Students’ Conversion Intentions. Can. J. Career Dev. 2019, 18, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Choudhury, M. Business school interns’ intention to join: Studying culture, work engagement and leader-member exchange in virtual internship. HESWBL 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, M.S.; Kavanagh, P.S.; Dollard, M.F. An Integrated Model of Work–Study Conflict and Work–Study Facilitation. J. Career Dev. 2018, 45, 504–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenette, A. Making the Intern Economy: Role and Career Challenges of the Music Industry Intern. Work. Occup. 2013, 40, 364–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Emmerik, H.; Sanders, K. Social embeddedness and job performance of tenured and non-tenured professionals. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2004, 14, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L.; Gifford, R.; Vlek, C. Factors influencing car use for commuting and the intention to reduce it: A question of self-interest or morality? Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G.; Bartels, J. The Norm Activation Model: An exploration of the functions of anticipated pride and guilt in pro-environmental behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 39, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. Environmental psychology matters. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 541–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Hunecke, M.; Blöbaum, A. Social context, personal norms and the use of public transportation: Two field studies. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, R.; Devine-Wright, P.; Mill, G.A. Comparing and Combining Theories to Explain Proenvironmental Intentions: The Case of Commuting-Mode Choice. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 731–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative explanations of helping behavior: A critique, proposal, and empirical test. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1973, 9, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, A.M.; Garvill, J. Value Structures behind Proenvironmental Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Gouveia, V.V.; Cameron, L.D.; Tankha, G.; Schmuck, P.; Franěk, M. Values and their Relationship to Environmental Concern and Conservation Behavior. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2005, 36, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.S.; Stern, P.C.; Elworth, J.T. Personal and contextual influences on househould energy adaptations. J. Appl. Psychol. 1985, 70, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.R.; Orwin, R.; Schurer, L. Defensive Denial and High Cost Prosocial Behavior. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 3, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.; Bondy, K.; Schuitema, G. Listen to others or yourself? The role of personal norms on the effectiveness of social norm interventions to change pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 78, 101688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, M.H.; Nguyen, P.M. Integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Norm Activation Model to Investigate Organic Food Purchase Intention: Evidence from Vietnam. Sustainability 2022, 14, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L.; Garvill, J.; Nordlund, A.M. Acceptability of travel demand management measures: The importance of problem awareness, personal norm, freedom, and fairness. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunecke, M.; Blöbaum, A.; Matthies, E.; Höger, R. Responsibility and Environment: Ecological norm orientation and external factors in the domain of travel mode choice behavior. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 830–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratt, C. The Impact of Norms and Assumed Consequences on Recycling Behavior. Environ. Behav. 1999, 31, 630–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizin, S.; van Dael, M.; van Passel, S. Battery pack recycling: Behaviour change interventions derived from an integrative theory of planned behaviour study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 122, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botetzagias, I.; Dima, A.-F.; Malesios, C. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior in the context of recycling: The role of moral norms and of demographic predictors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 95, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldo, R.; Castro, P. The outer influence inside us: Exploring the relation between social and personal norms. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 112, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, B.F.; Bishop, J.W.; Govindarajulu, N. A Conceptual Model for Organizational Citizenship Behavior Directed toward the Environment. Bus. Soc. 2009, 48, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.H.; van Breukelen, G.J.; Peters, G.-J.Y.; Kok, G. Proenvironmental travel behavior among office workers: A qualitative study of individual and organizational determinants. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2013, 56, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. Morality and Prosocial Behavior: The Role of Awareness, Responsibility, and Norms in the Norm Activation Model. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 149, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Elicitation of moral obligation and self-sacrificing behavior: An experimental study of volunteering to be a bone marrow donor. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1970, 15, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. J. Soc. Isssues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg, S.; Schmidt, P. Incentives, Morality, or Habit? Predicting Students’ Car Use for University Routes with the Models of Ajzen, Schwartz, and Triandis. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Organisational sustainability policies and employee green behaviour: The mediating role of work climate perceptions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Parker, S.L.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Bridging the gap between green behavioral intentions and employee green behavior: The role of green psychological climate. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 996–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.J.; Borucki, C.C.; Kaufman, J.D. Contemporary perspectives on the study of psychological climate: A commentary. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2002, 11, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuenzi, M.; Schminke, M. Assembling Fragments into a Lens: A Review, Critique, and Proposed Research Agenda for the Organizational Work Climate Literature. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 634–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.G.; West, M.A.; Shackleton, V.J.; Dawson, J.F.; Lawthom, R.; Maitlis, S.; Robinson, D.L.; Wallace, A.M. Validating the organizational climate measure: Links to managerial practices, productivity and innovation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 379–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; Ehrhart, M.G.; Macey, W.H. Organizational climate and culture. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Kelley, K. The Effects of Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility on Employee Attitudes. Bus. Ethics Q. 2014, 24, 165–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Carleton, E. Uncovering How and When Environmental Leadership Affects Employees’ Voluntary Pro-environmental Behavior. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2018, 25, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magill, M.S.; Yost, P.R.; Chighizola, B.; Stark, A. Organizational climate for climate sustainability. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2020, 72, 198–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. On the Importance of Pro-Environmental Organizational Climate for Employee Green Behavior. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 5, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N.; Fouquereau, E.; Forest, J.; Brunault, P.; Colombat, P. The Impact of Organizational Factors on Psychological Needs and Their Relations with Well-Being. J. Bus. Psychol. 2012, 27, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamm, E.; Tosti-Kharas, J.; King, C.E. Empowering Employee Sustainability: Perceived Organizational Support toward the Environment. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manika, D.; Wells, V.K.; Gregory-Smith, D.; Gentry, M. The Impact of Individual Attitudinal and Organisational Variables on Workplace Environmentally Friendly Behaviours. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 663–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Parker, S.L.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Employee Green Behavior: A Theoretical Framework, Multilevel Review, and Future Research Agenda. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raineri, N.; Paillé, P. Linking Corporate Policy and Supervisory Support with Environmental Citizenship Behaviors: The Role of Employee Environmental Beliefs and Commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.A.; Killmer, A.B.C. Corporate greening through prosocial extrarole behaviours—A conceptual framework for employee motivation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2007, 16, 554–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Sial, M.S.; Ahmad, N.; Sehleanu, M.; Li, Z.; Zia-Ud-Din, M.; Badulescu, D. CSR as a Potential Motivator to Shape Employees’ View towards Nature for a Sustainable Workplace Environment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado Astudillo, R.I.; Maldonado Astudillo, Y.P.; Méndez Zavala, J.A.; Manzano Jiménez, C.L.; Astudillo Miller, M.X. Corporate Social Responsibility and Proenvironmental Behaviour in Employees: Evidence in Acapulco, Mexico. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.A.; Steger, U. The Roles of Supervisory Support Behaviors and Environmental Policy in Employee Ecoinitiatives at Leading-Edge European Companies. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 605–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C.A. Organizational Support for Employees: Encouraging Creative Ideas for Environmental Sustainability. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2001, 43, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, J.W.; Scott, K.D.; Burroughs, S.M. Support, Commitment, and Employee Outcomes in a Team Environment. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 1113–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossholder, K.W.; Settoon, R.P.; Henagan, S.C. A Relational Perspective on Turnover: Examining Structural, Attitudinal, and Behavioral Predictors. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldner, A.W. The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Frenkel, S.J. Explaining task performance and creativity from perceived organizational support theory: Which mechanisms are more important? J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 1165–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Chiaburu, D.S.; Kirkman, B.L. Cross-Level Influences of Empowering Leadership on Citizenship Behavior. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1076–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhou, K.; Che, Y.; Han, Y. Promoting employees’ pro-environmental behaviour through empowering leadership: The roles of psychological ownership, empowerment role identity, and environmental self-identity. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2021, 30, 604–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Round, H.; Bhattacharya, S.; Roy, A. Ethical Climates in Organizations: A Review and Research Agenda. Bus. Ethics Q. 2017, 27, 475–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Cheema, S.; Javed, F. Activating employee’s pro-environmental behaviors: The role of CSR, organizational identification, and environmentally specific servant leadership. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraz, N.A.; Ahmed, F.; Ying, M.; Mehmood, S.A. The interplay of green servant leadership, self-efficacy, and intrinsic motivation in predicting employees’ pro-environmental behavior. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1171–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, S. Drivers of Proactive Environmental Strategy in Family Firms. Bus. Ethics Q. 2011, 21, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; van Kasteren, Y.; Louis, W.; McKenna, B.; Russell, S.; Spinks, A. Using individual householder survey responses to predict household environmental outcomes: The cases of recycling and water conservation. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 106, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.B.; Iyer, E.S.; Kashyap, R.K. Corporate Environmentalism: Antecedents and Influence of Industry Type. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-J. Hotels’ environmental policies and employee personal environmental beliefs: Interactions and outcomes. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrend, T.S.; Baker, B.A.; Thompson, L.F. Effects of Pro-Environmental Recruiting Messages: The Role of Organizational Reputation. J. Bus. Psychol. 2009, 24, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Ansari, N.; Raza, A.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H. Fostering employee’s pro-environmental behavior through green transformational leadership, green human resource management and environmental knowledge. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 179, 121643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of Green HRM Practices on Employee Workplace Green Behavior: The Role of Psychological Green Climate and Employee Green Values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Stanley, D.J.; Herscovitch, L.; Topolnytsky, L. Affective, Continuance, and Normative Commitment to the Organization: A Meta-analysis of Antecedents, Correlates, and Consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 61, 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997; ISBN 9780761901051. [Google Scholar]

- Mercurio, Z.A. Affective Commitment as a Core Essence of Organizational Commitment. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2015, 14, 389–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Steers, R.M.; Porter, L.W. The measurement of organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1979, 14, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Herscovitch, L. Commitment in the workplace: Toward a general model. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2001, 11, 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marique, G.; Stinglhamber, F.; Desmette, D.; Caesens, G.; de Zanet, F. The Relationship between Perceived Organizational Support and Affective Commitment. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 68–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.; Ostertag, F. Disentangling voluntary pro-environmental behaviour of employees (VPBE)—Fostering research through an integrated theoretical model. In Research Handbook on Employee Pro-Environmental Behaviour; Wells, V., Gregory-Smith, D., Manika, D., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 83–105. ISBN 9781786432834. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Panagopoulos, N.G.; Rapp, A.A. Employee judgments of and behaviors toward corporate social responsibility: A multi-study investigation of direct, cascading, and moderating effects. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 990–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, M.; Zibarras, L.D.; Stride, C. Using the theory of planned behavior to explore environmental behavioral intentions in the workplace. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulhus, D.L.; Vazire, S. The self-report method. In Handbook of Research Methods in Personality Psychology; Robins, R.W., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 224–239. ISBN 978-1-60623-612-3. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, J.M.; Lance, C.E. What Reviewers Should Expect from Authors Regarding Common Method Bias in Organizational Research. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Predictive validity of the theory of planned behaviour: The role of questionnaire format and social desirability. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 9, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormos, C.; Gifford, R. The validity of self-report measures of proenvironmental behavior: A meta-analytic review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, A.H.; van der Werff, B.R.; Henning, J.B.; Watrous-Rodriguez, K. When do recycling attitudes predict recycling?: An investigation of self-reported versus observed behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krettenauer, T.; Lefebvre, J.P. Beyond subjective and personal: Endorsing pro-environmental norms as moral norms. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 76, 101644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Godwin, L.N. Is the Perception of ‘Goodness’ Good Enough? Exploring the Relationship between Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Organizational Identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkin, T.R. A Brief Tutorial on the Development of Measures for Use in Survey Questionnaires. Organ. Res. Methods 1998, 1, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissing-Olson, M.J.; Iyer, A.; Fielding, K.S.; Zacher, H. Relationships between daily affect and pro-environmental behavior at work: The moderating role of pro-environmental attitude. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, A.; Stolberg, A. Explaining pro-environmental behavior with a cognitive theory of stress. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Doka, G.; Hofstetter, P.; Ranney, M.A. Ecological behavior and its environmental consequences: A life cycle assessment of a self-report measure. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, J.A.; DeGeest, D.; Li, A. Tackling the problem of construct proliferation: A guide to assessing the discriminant validity of conceptually related constructs. Organ. Res. Methods 2016, 19, 80–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; de Groot, J.I.M. Explaining prosocial intentions: Testing causal relationships in the norm activation model. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 49, 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O’Neill, S. Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse pro-environmental behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. Value Orientations and Environmental Beliefs in Five Countries: Validity of an Instrument to Measure Egoistic, Altruistic and Biospheric Value Orientations. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2007, 38, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. Value Orientations to Explain Beliefs Related to Environmental Significant Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 330–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Dreijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W. Factors influencing the acceptability of energy policies: A test of VBN theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Armeli, S.; Rexwinkel, B.; Lynch, P.D.; Rhoades, L. Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D. The Quest to Improve the Human Condition: The First 1500 Articles Published in Journal of Business Ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 26, 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Fallon, M.J.; Butterfield, K.D. A Review of The Empirical Ethical Decision-Making Literature: 1996–2003. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 59, 375–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Palomino, P.; Bañón-Gomis, A.; Linuesa-Langreo, J. Impacts of peers’ unethical behavior on employees’ ethical intention: Moderated mediation by Machiavellian orientation. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2019, 28, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, T.E. Potential Problems in the Statistical Control of Variables in Organizational Research: A Qualitative Analysis with Recommendations. Organ. Res. Methods 2005, 8, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernerth, J.B.; Aguinis, H. A Critical Review and Best-Practice Recommendations for Control Variable Usage. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 69, 229–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Brannick, M.T. Methodological Urban Legends: The Misuse of Statistical Control Variables. Organ. Res. Methods 2011, 14, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Zelezny, L.C. Values and Proenvironmental Behavior: A Five-Country Survey. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1998, 29, 540–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Wilson, M. Assessing People’s General Ecological Behavior: A Cross-Cultural Measure. J. Appl. Soc. Pyschol. 2000, 30, 952–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Oerke, B.; Bogner, F.X. Behavior-based environmental attitude: Development of an instrument for adolescents. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swim, J.K.; Becker, J.C. Country Contexts and Individuals’ Climate Change Mitigating Behaviors: A Comparison of U.S. versus German Individuals’ Efforts to Reduce Energy Use. J. Soc. Isssues 2012, 68, 571–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzini, P.; Thøgersen, J. Behavioural spillover in the environmental domain: An intervention study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Mosquera, N.; Lera-López, F.; Sánchez, M. Key factors to explain recycling, car use and environmentally responsible purchase behaviors: A comparative perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 99, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhead, R.; Elliot, M.; Upham, P. Assessing the structure of UK environmental concern and its association with pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balundė, A.; Perlaviciute, G.; Steg, L. The Relationship between People’s Environmental Considerations and Pro-Environmental Behavior in Lithuania. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F.; Rice, J. Little Jiffy, Mark IV. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziuban, C.D.; Shirkey, E.C. When is a correlation matrix appropriate for factor analysis?: Some decision rules. Psychol. Bull. 1974, 81, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Giering, A. Konzeptualisierung und Operationalisierung komplexer Konstrukte: Ein Leitfaden für die Marketingforschung. Mark. ZFP J. Res. Manag. 1996, 18, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed.; Taylor and Francis: Florence, Italy, 2016; ISBN 9781138797024. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Scheer, L.K.; Steenkamp, J.-B.E.M. The Effects of Supplier Fairness on Vulnerable Resellers. J. Mark. Res. 1995, 32, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2018; ISBN 9781462534654. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, L.M.; Sarkis, J. The role of employees’ leadership perceptions, values, and motivation in employees’ provenvironmental behaviors. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, J.; Terry, D.J. Volunteer Decision Making by Older People: A Test of a Revised Theory of Planned Behavior. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 22, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, L.A. Dispositional and Organizational Influences on Sustained Volunteerism: An Interactionist Perspective. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 58, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W.; Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Its Nature, Antecedents, and Consequences; SAGE Publications, Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780761929963. [Google Scholar]

- Mouro, C.; Duarte, A.P. Organisational Climate and Pro-Environmental Behaviours at Work: The Mediating Role of Personal Norms. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 635739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liang, J.; Yang, J.; Ma, X.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Yang, G.; Ren, G.; Feng, Y. Analysis of the environmental behavior of farmers for non-point source pollution control and management: An integration of the theory of planned behavior and the protection motivation theory. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 237, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujitani, M.L.; Riepe, C.; Pagel, T.; Buoro, M.; Santoul, F.; Lassus, R.; Cucherousset, J.; Arlinghaus, R. Ecological and social constraints are key for voluntary investments into renewable natural resources. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2020, 63, 102125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, R.H.; Blakely, G.L.; Niehoff, B.P. Does Perceived Organizational Support Mediate the Relationship between Procedural Justice and Organizational Citizenship Behavior? Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Grima, F.; Dufour, M.-È. Contribution to social exchange in public organizations: Examining how support, trust, satisfaction, commitment and work outcomes are related. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 520–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staats, H.; van Leeuwen, E.; Wit, A. A longitudinal study of informational interventions to save energy in an office building. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2000, 33, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, D.R. What is the Difference between Organizational Culture and Organizational Climate?: A Native’s Point of View on a Decade of Paradigm Wars. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 619–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, B.B.; Afsar, B.; Hafeez, S.; Khan, I.; Tahir, M.; Afridi, M.A. Promoting employee’s proenvironmental behavior through green human resource management practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, M.; Kaptein, M. Virtue and virtuousness in organizations: Guidelines for ascribing individual and organizational moral responsibility. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2021, 30, 801–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronrod, A.; Tchetchik, A.; Grinstein, A.; Turgeman, L.; Blass, V. Promoting new pro-environmental behaviors: The effect of combining encouraging and discouraging messages. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 86, 101945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rua, T.; Lawter, L.; Andreassi, J. Desire to be ethical or ability to self-control: Which is more crucial for ethical behavior? Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2017, 26, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. Do Not Cross Me: Optimizing the Use of Cross-Sectional Designs. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 34, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taris, T.W.; Kessler, S.R.; Kelloway, E.K. Strategies addressing the limitations of cross-sectional designs in occupational health psychology: What they are good for (and what not). Work Stress 2021, 35, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, A.M.; Corrigall, E.; Lieb, P.; Ritchie, J.E., Jr. Sex Differences in Job Attribute Preferences among Managers and Business Students. Group Organ. Manag. 2000, 25, 108–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, G.C.; Batchelor, J.H.; Seers, A.; O’Boyle, E.H.; Pollack, J.M.; Gower, K. What does team-member exchange bring to the party?: A meta-analytic review of team and leader social exchange. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettis, R.A.; Hitt, M.A. The new competitive landscape. Strat. Manag. J. 1995, 16, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaburu, D.S.; Harrison, D.A. Do peers make the place? Conceptual synthesis and meta-analysis of coworker effects on perceptions, attitudes, OCBs, and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1082–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chomvilailuk, R.; Butcher, K. How hedonic and perceived community benefits from employee CSR involvement drive CSR advocacy behavior to co-workers. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2022, 31, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O. Tacit Knowledge and Environmental Management. Long Range Plan. 2002, 35, 291–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJonghe, N.; Doctori-Blass, V.; Ramus, C.A. Employee eco-initiatives: Case studies of two eco-entrepreneurial companies. In Frontiers in Eco-Entrepreneurship Research, 1st ed.; Libecap, G.D., Ed.; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2009; pp. 79–125. ISBN 978-1-8485-5950-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Sorensen, K.L. Toward a Further Understanding of the Relationships between Perceptions of Support and Work Attitudes. Group Organ. Manag. 2008, 33, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, R.O.; Burciaga, A. Organizational environmental orientation and employee environmental in-role behaviors: A cross-level study. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2020, 29, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ostertag, F. Integrating OCBE Literature and Norm Activation Theory: A Moderated Mediation on Proenvironmental Behavior of Employees. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097605

Ostertag F. Integrating OCBE Literature and Norm Activation Theory: A Moderated Mediation on Proenvironmental Behavior of Employees. Sustainability. 2023; 15(9):7605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097605

Chicago/Turabian StyleOstertag, Felix. 2023. "Integrating OCBE Literature and Norm Activation Theory: A Moderated Mediation on Proenvironmental Behavior of Employees" Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097605

APA StyleOstertag, F. (2023). Integrating OCBE Literature and Norm Activation Theory: A Moderated Mediation on Proenvironmental Behavior of Employees. Sustainability, 15(9), 7605. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097605