Knowledge, Competencies, and Skills for a Sustainable Sport Management Growth: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

“As sport changes, what is required to be a competent sports manager is transformed”.(cit. Hoye, 2004 [1]).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Search within European Professional Databases

2.2. Protocol and Eligibility Criteria for the Systematic Literature Review

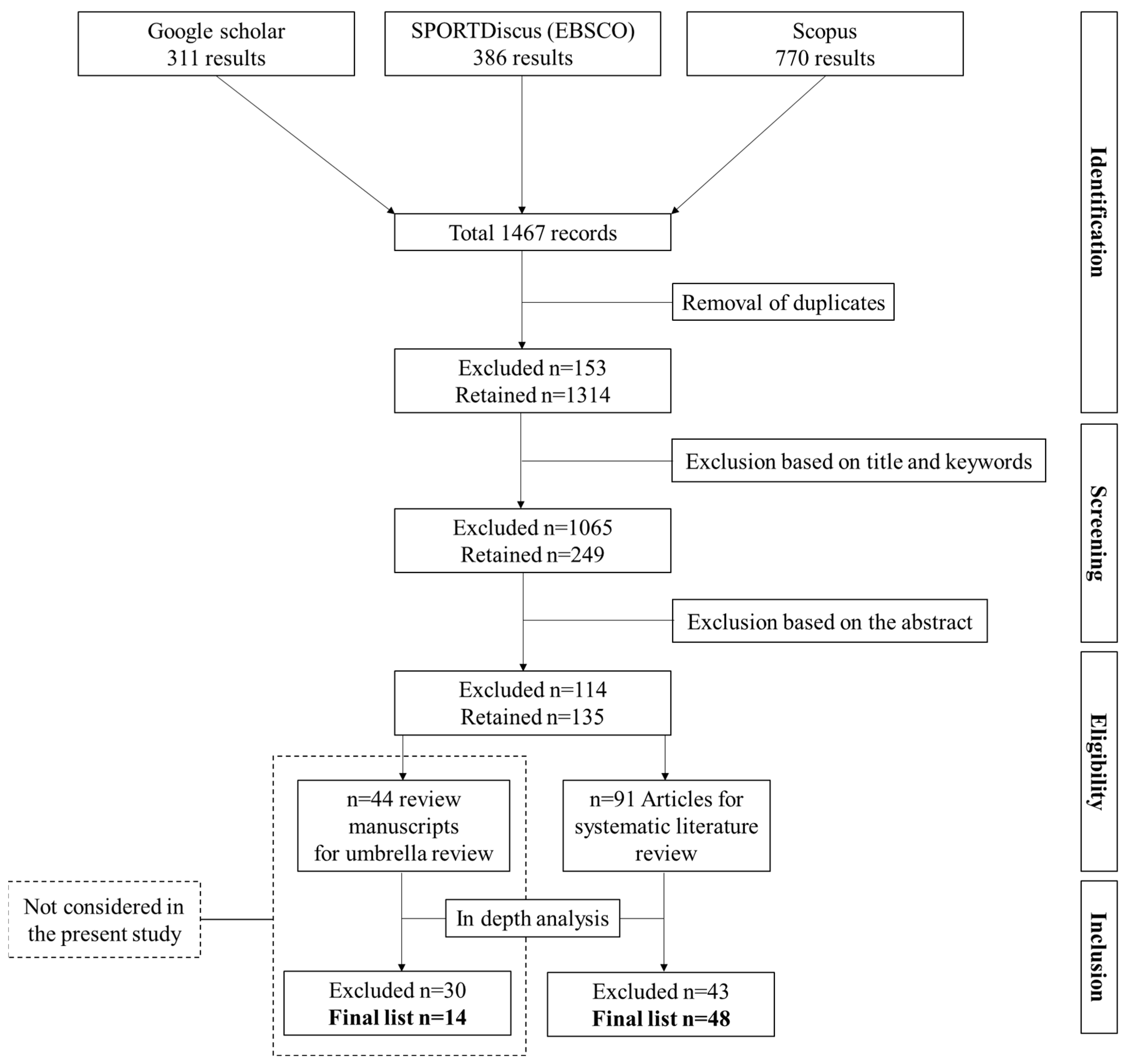

2.3. Literature Search Process

2.4. Study Selection and Data Collection Process

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. European Framework for Sport Management Related Occupations and Relevant K/C/S

3.2. General Findings from the Systematic Literature Review

| Ref. | Authors and Year | Research Context | Country | Continent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [40] | Parent et al., 2012 | Sport events | Canada and Norway | Mixed |

| [41] | Bravo et al., 2012 | Collegiate athletic administration | United States | North America |

| [42] | Arnold et al., 2012 | Leadership in sport organizations | United Kingdom | Europe |

| [25] | Emery et al., 2012 | Employability and work in sport management | Australia | Oceania |

| [43] | Won et al., 2013 | Collegiate athletic administration | United States | North America |

| [44] | Pauline, 2013 | Sport events | United States | North America |

| [45] | Eksteen et al., 2013 | Sport organizations | South Africa | Africa |

| [46] | Hardin et al., 2013 | Collegiate athletic administration | United States | North America |

| [47] | Shahram and Mehran, 2013 | Sport organizations | Iran | Asia |

| [48] | Jones and Jones, 2014 | Sport management education | United Kingdom | Europe |

| [49] | Diacin and VanSickle, 2014 | Sport organizations | United States | North America |

| [50] | Fang and Kim, 2014 | Sport management education | China, Japan, Korea and Taiwan | Asia |

| [51] | Benar et al., 2014 | Leadership in sport organizations | Iran | Asia |

| [52] | Misener and Doherty, 2014 | Sport organizations | Canada | North America |

| [53] | Eksteen et al., 2015 | Sport management education | South Africa | Africa |

| [54] | DeLuca and Braunstein-Minkove, 2016 | Sport management education | United States | North America |

| [55] | Marjoribanks and Farquharson, 2016 | Leadership in sport organizations | Australia | Oceania |

| [56] | Molan et al., 2016 | Leadership in sport organizations | Ireland | Europe |

| [57] | Wemmer and Koenigstorfer, 2016 | Sport organizations | Germany | Europe |

| [58] | Magnusen and Kim, 2016 | Sport management education | United States | North America |

| [59] | Tsitskari et al., 2017 | Employability and work in sport management | Greece | Europe |

| [60] | Megheirkouni, 2017 | Leadership in sport organizations | Syria | Asia |

| [61] | Dinning, 2017 | Employability and work in sport management | United Kingdom | Europe |

| [62] | Freitas et al., 2017 | Leadership in sport organizations | Brazil | South America |

| [63] | Megheirkouni and Roomi, 2017 | Leadership in sport organizations | United Kingdom | Europe |

| [64] | Shreffler et al., 2018 | Employability and work in sport management | United States | North America |

| [23] | Fahrner and Schüttoff, 2019 | Employability and work in sport management | Germany | Europe |

| [65] | Pierce, 2019 | Sport management education | United States | North America |

| [66] | Wohlfart et al., 2019 | Employability and work in sport management | Germany, Norway, and Spain | Europe |

| [67] | O’Boyle et al., 2019 | Leadership in sport organizations | Australia | Oceania |

| [13] | Ströbel et al., 2020 | Sport management education | Germany and United States | Mixed |

| [68] | DeLuca et al., 2020 | Sport management education | United States | North America |

| [69] | de Schepper et al., 2020 | Employability and work in sport management | The Netherlands | Europe |

| [70] | Pate and Bosley, 2020 | Sport management education | United States | North America |

| [71] | Sattler and Achen, 2021 | Employability and work in sport management | United States | North America |

| [12] | Wohlfart et al., 2021 | Employability and work in sport management | Germany | Europe |

| [72] | Omrčen, 2021 | Sport management education | Croatia | Europe |

| [73] | Duclos-Bastíaset al., 2021 | Sport organizations | Chile | South America |

| [74] | Sauder et al., 2021 | Sport management education | United States | North America |

| [75] | Escamilla-Fajardo et al., 2021 | Sport organizations | Spain | Europe |

| [76] | Lu, 2021 | Sport management education | Taiwan | Asia |

| [77] | López-Carril et al., 2021 | Sport management education | Spain | Europe |

| [22] | Nová, 2021 | Sport organizations | Nine EU countries (NASME project) | Europe |

| [78] | Robinson et al., 2021 | Collegiate athletic administration | United States | North America |

| [79] | Veraldo and Yost, 2021 | Sport management education | United States | North America |

| [80] | Finch et al., 2021 | Employability and work in sport management | United States | North America |

| [81] | Davies and Ströbel, 2022 | Sport management education | Germany and United States | Mixed |

| [82] | Atilgan and Kaplan, 2022 | Sport organizations | Turkey | Europe |

3.3. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3.1. Emerging Topics

3.3.2. Methodologies, Instruments, Participants’ Characteristics, and Quality Assessment of the Included Studies

3.4. Relevant K/C/S Extracted from the Included Studies

3.5. Comparison between K/C/S in the ESCO Platform and in the Scientific Literature

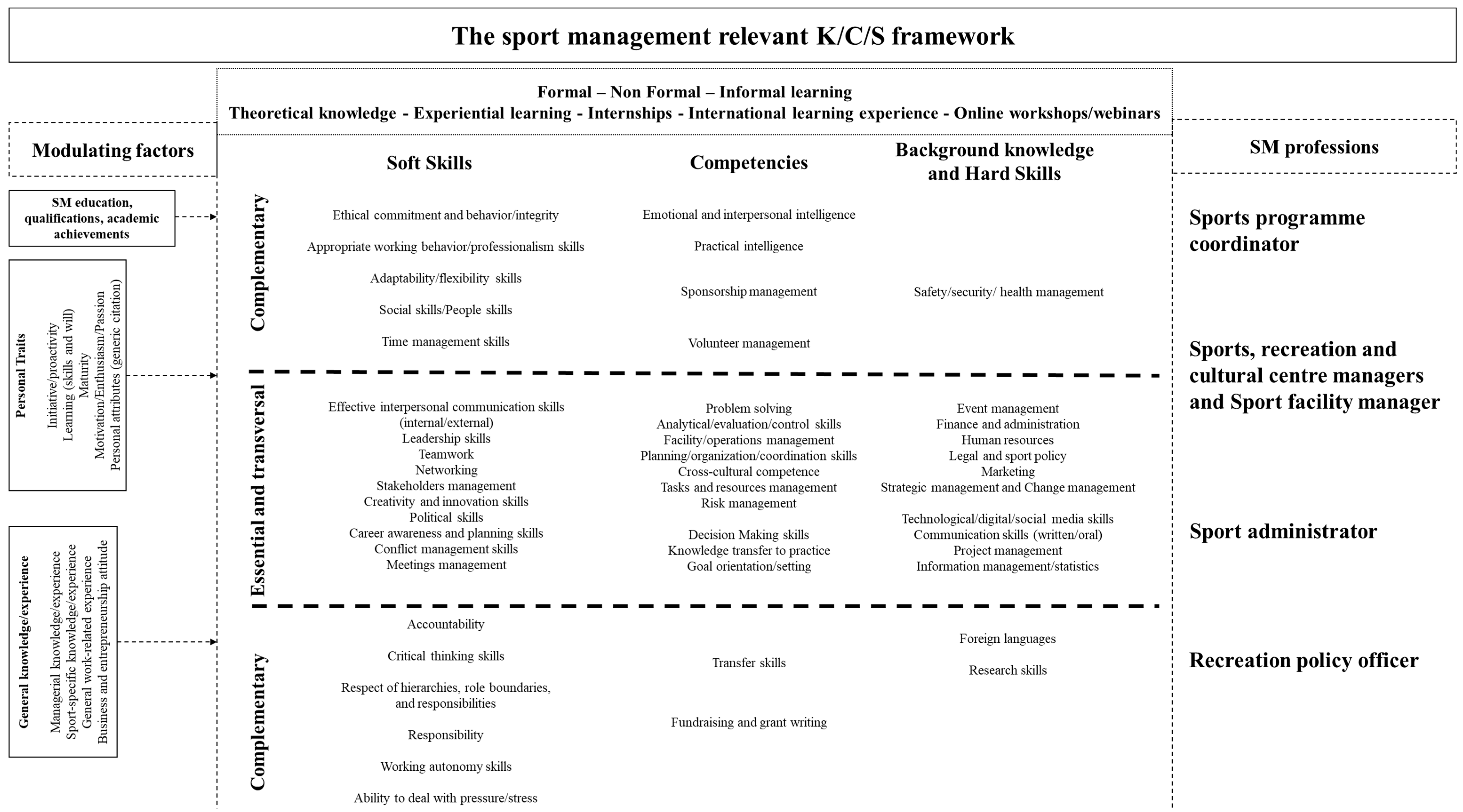

3.6. Harmonized K/C/S Framework Derived from the Scientific Findings

- Core relevant aspects pertaining to essential and transversal BK, HS, C, and SS have positioned at the core;

- Additional, complementary, emerged BK, HS, C, and SS have positioned at the superior and inferior edges, based on their potential relevance and/or pertinence in relation to the different sport management professional profiles;

- Academic preparation and achievements, GE, and PT/A have been considered as modulating factors, further enriching the sport management professional in succeeding in the labor market;

- A comprehensive and harmonized approach, including different types of learning (i.e., formal, non-formal, and informal) in relation to both theoretical knowledge and practical experience (i.e., experiential learning, internships, workshops), and in a global perspective (i.e., internationalization) should be considered in educating future sport management professionals. In fact, to allow sport managers to progress vertically, to move horizontally, and/or to operate transversal working shifts during their professional career, it is crucial to equip them with a wide variety of K/C/S to be developed though different approaches and/or training methodologies.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoye, R. Leader-member exchanges and board performance of voluntary sport organisations. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2004, 15, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitts, B.G.; Stotlar, D.K. Fundamentals of Sport Marketing, 5th ed.; Fitness Information Technology: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Study on the Economic Impact of Sport through Sport Satellite Accounts. Research Report. 2018. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/865ef44c-5ca1-11e8-ab41-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-71256399 (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Zhang, J.J.; Breedlove, J.; Kim, A.; Bo, H.H.; Anderson, D.J.F.; Zhao, T.T.; Johnoson, L.; Pitts, B. Issues and new ideas in international sport management: An introduction. In International Sport Business Management, 1st ed.; Zhang, J.J., Pitts, B.G., Johnson, L.M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, G.B.; Fink, J.S.; Zhang, J.J. The Distinctiveness of Sport Management Theory and Research. Kinesiol. Rev. 2021, 10, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nová, J. Developing the entrepreneurial competencies of sport management students. Procedia Soc. 2015, 174, 3916–3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutović, T.; Relja, R.; Popović, T. The constitution of profession in a sociological sense: An example of sports management. Econ. Sociol. 2020, 13, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COSMA. Promoting Excellence in Sport Management Education Worldwide. 2023. Available online: https://www.cosmaweb.org/ (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- NASSM. North American Society for Sport Management. 2023. Available online: https://nassm.org/ (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- EASM. European Association for Sport Management. 2023. Available online: https://www.easm.net/general-information/ (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Miragaia, D.A.M.; Soares, J.A.P. Higher education in sport management: A systematic review of research topics and trends. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2017, 21, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfart, O.; Adam, S.; Hovemann, G. Aligning competence-oriented qualifications in sport management higher education with industry requirements: An importance–performance analysis. Ind. High. 2021, 36, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ströbel, T.; Ridpath, B.D.; Woratschek, H.; O’Reilly, N.; Buser, M.; Pfahl, M. Co-branding through an international double degree program: A single case study in sport management education. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2020, 14, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifried, C.S. A review of the North American Society for Sport Management and its foundational core—Mapping the influence of “history”. J. Manag. Hist. 2014, 20, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piovani, V.G.S.; Vieira, S.V.; Both, J.; Rinaldi, I.P.B. Internship at Sport Science undergraduate courses: A scoping review. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2019, 27, 100233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, L.; Mahoney, T.Q.; Lovich, J.M.; Scialabba, N. Practice makes perfect: Practical experiential learning in sport management. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 2018, 89, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Association for Sport Management. 2023. Available online: https://wasmorg.com/about/evolution-of-wasm/ (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Cunningham, G.B. Theory and theory development in sport management. Sport Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, G.B.; Fink, J.S.; Doherty, A. Developing theory in sport management. In Routledge Handbook of Theory in Sport Management; Cunningham, G.B., Fink, J.S., Doherty, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ciomaga, B. Sport management: A bibliometric study on central themes and trends. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2013, 13, 557–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.M.; Batista, P.; Carvalho, M.J. Framing sport managers’ profile: A systematic review of the literature between 2000 and 2019. SPORT TK-Rev. EuroAmericana Cienc. Deporte 2022, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nová, J. New directions for professional preparation—A competency-based model for training sport management personnel. In Sport Governance and Operations, 1st ed.; Euisoo, K., Zhang, J.J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 244–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrner, M.; Schüttoff, U. Analysing the context-specific relevance of competencies—Sport management alumni perspectives. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2019, 20, 344–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Higher Education Area and Bologna Process. 2023. Available online: http://www.ehea.info/index.php (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Emery, P.R.; Crabtree, R.M.; Kerr, A.K. The Australian sport management job market: An advertisement audit of employer need. Ann. Leis. Res. 2012, 15, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoye, R.; Smith, A.C.T.; Nicholson, M.; Stewart, B. Sport Management Principles and Applications, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, L.M. Competency-based approaches to sport management. J. Sport Manag. 1987, 1, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.A. The status and future of sport management: A Delphi study. J. Sport Manag. 2005, 19, 117–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Towards More Gender Equality in Sport—Recommendations and Action Plan from the High Level Group on Gender Equality in Sport. 2022. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/684ab3af-9f57-11ec-83e1-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- UN General Assembly. Resolution Adopted on 25 September 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/291/89/PDF/N1529189.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- European Parliament. Motion for a European Parliament Resolution on EU Sports Policy: Assessment and Possible Ways Forward. 2021. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2021-0318_EN.html (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Council of Europe. European Convention of Human Rights. 2021. Available online: https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/convention_eng.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Moore, M.E.; Huberty, L. Gender differences in a growing industry: A case of sport management education. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Invent. 2014, 3, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, A.B.; Pfister, G.U. Women in sports leadership: A systematic narrative review. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport. 2021, 56, 317–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Miracle Project. Women’s Empowerment in Sport and Physical Education Industry. 2023. Available online: http://www.newmiracle.simplex.lt/ (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- European Skills, Competences, Qualifications and Occupations (ESCO). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/esco/portal/home?resetLanguage=true&newLanguage=en (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/esco/portal/escopedia/International_Standard_Classification_of_Occupations__40_ISCO_41_?resetLanguage=true&newLanguage=en (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagno, M.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018. Registration of Copyright (#1148552). Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada. 2018. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Parent, M.M.; Eskerud, L.; Hanstad, D.V. Brand creation in international recurring sports events. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, G.; Won, D.; Shonk, D.J. Entry-Level Employment in Intercollegiate Athletic Departments: Non-Readily Observables and Readily Oberservable Attributes of Job Candidates. J. Appl. Sport Manag. 2012, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, R.; Fletcher, D.; Molyneux, L. Performance leadership and management in elite sport: Recommendations, advice and suggestions from national performance directors. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2012, 12, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, D.; Bravo, G.; Lee, C. Careers in collegiate athletic administration: Hiring criteria and skills needed for success. Manag. Sport Leis. 2013, 18, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauline, G. Engaging students beyond just the experience: Integrating reflection learning into sport event management. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2013, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eksteen, E.; Malan, D.D.J.; Lotriet, R. Management competencies of sport club managers in the North-West Province, South Africa. Afr. J. Phys. Health Educ. Recreat. Danc. 2013, 19, 928–936. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, R.; Cooper, C.G.; Huffman, L.T. Moving on up: Division I athletic directors’ career progression and involvement. JASM 2013, 5, 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Shahram, S.; Mehran, N. Relationship Between Communicational Skills and Barriers to Individual Creativity of Sport Boards of Guilan. Choregia 2013, 9, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Jones, A. Attitudes of Sports Development and Sports Management undergraduate students towards entrepreneurship: A university perspective towards best practice. Educ. Train. 2014, 56, 716–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diacin, M.J.; VanSickle, J.L. Computer program usage in sport organizations and computer competencies desired by sport organization personnel. Int. J. Appl. Sports Sci. 2014, 26, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, E.S.Y.; Kim, C. Construction of sports business professional competence cultivation indicators in Asian higher education. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. 2014, 36, 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Benar, N.; Ramezani Nejad, R.; Surani, M.; Gohar Rostami, H.; Yeganehfar, N. Designing a Managerial Skills Model for Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) of Professional Sports Clubs in Isfahan Province. Sport Sci. Rev. 2014, 23, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misener, K.; Doherty, A. In support of sport: Examining the relationship between community sport organizations and sponsors. Sport Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eksteen, E.; Willemse, Y.; Malan, D.D.J.; Ellis, S. Competencies and training needs for school sport managers in the North- west Province of South Africa. J. Phys. Educ. Sport Manag. 2015, 6, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLuca, J.R.; Braunstein-Minkove, J. An evaluation of sport management student preparedness: Recommendations for adapting curriculum to meet industry needs. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2016, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjoribanks, T.; Farquharson, K. Contesting competence: Chief executive officers and leadership in Australian Football League clubs. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2016, 34, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molan, C.; Matthews, J.; Arnold, R. Leadership off the pitch: The role of the manager in semi-professional football. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2016, 16, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wemmer, F.; Koenigstorfer, J. Open innovation in nonprofit sports clubs. Voluntas 2016, 27, 1923–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusen, M.; Kim, J.W. Thriving in the political sport arena: LMX as a mediator of the political skill–career success relationship. J. Appl. Sport Manag. 2016, 8, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitskari, E.; Goudas, M.; Tsalouchou, E.; Michalopoulou, M. Employers’ expectations of the employability skills needed in the sport and recreation environment. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2017, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megheirkouni, M. Leadership competencies: Qualitative insight into non-profit sport organisations. Int. J. Public Leadersh. 2017, 13, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinning, T. Preparing sports graduates for employment: Satisfying employers expectations. High. Educ. Ski. 2017, 7, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, D.; Girginov, V.; Teoldo, I. What do they do? Competency and managing in Brazilian Olympic Sport Federations. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2017, 17, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megheirkouni, M.; Roomi, M.A. Women’s leadership development in sport settings: Factors influencing the transformational learning experience of female managers. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2017, 41, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreffler, M.B.; Schmidt, S.H.; Weiner, J. Sales training in career preparation: An examination of sales curricula in sport management education. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2018, 12, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, D. Analysis of sport sales courses in the sport management curriculum. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2019, 24, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfart, O.; Adam, S.; García-Unanue, J.; Hovemann, G.; Skirstad, B.; Strittmatter, A.M. Internationalization of the sport management labor market and curriculum perspectives: Insights from Germany, Norway, and Spain. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2019, 14, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Boyle, I.; Shilbury, D.; Ferkins, L. Toward a working model of leadership in nonprofit sport governance. J. Sport Manag. 2019, 33, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLuca, J.R.; Mudrick, M.T.; Sauder, M.H. Optimistic & Boundaryless: Sport Management Students’ Conceptualization of Career. Schole 2020, 35, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Schepper, J.; Sotiriadou, P.; Hill, B. The role of critical reflection as an employability skill in sport management. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2021, 21, 280–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, J.R.; Bosley, A.T. Understanding the skills and competencies athletic department social media staff seek in sport management graduates. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2020, 14, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, L.; Achen, R. A foot in the door: An examination of professional sport internship job announcements. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2021, 15, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omrčen, D. An assessment of the importance of language skills and vocabulary knowledge in a foreign language: The case for sport management. J. Engl. Acad. 2021, 9, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duclos-Bastías, D.; Giakoni-Ramírez, F.; Parra-Camacho, D.; Rendic-Vera, W.; Rementería-Vera, N.; Gajardo-Araya, G. Better managers for more sustainability SOs: Validation of sports managers competency scale (COSM) in Chile. Sustainability 2021, 13, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauder, M.H.; DeLuca, J.R.; Mudrick, M.; Taylor, E. Conceptualization of diversity and inclusion: Tensions and contradictions in the sport management classroom. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2021, 29, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla-Fajardo, P.; Alguacil, M.; Gómez-Tafalla, A.M. Effects of entrepreneurial orientation and passion for work on performance variables in sports clubs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.F. Enhancing university student employability through practical experiential learning in the sport industry: An industry-academia cooperation case from Taiwan. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2021, 28, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Carril, S.; Villamón, M.; González-Serrano, M.H. Linked (In) g sport management education with the sport industry: A preliminary study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, G.M.; Magnusen, M.J.; Neubert, M.; Miller, G. Servant leadership, leader effectiveness, and the role of political skill: A study of interscholastic sport administrators and coaches. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2021, 16, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraldo, C.M.; Yost, D. Service learning and travel abroad in the Dominican Republic: Developing competencies for international sport management. Int. J. Sport Manag. 2021, 22, 170–194. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, D.J.; O’Reilly, N.; Legg, D.; Levallet, N.; Fody, E. So you want to work in sports? An exploratory study of sport business employability. Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2022, 12, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.; Ströbel, T. Global Sport Management Learning from Home: Expanding the International Sport Management Experience Through a Collaborative Class Project. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2022, 16, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atilgan, D.; Kaplan, T. Investigation of the relationship among crisis management, decision-making and self-confidence based on sport managers in Turkey. Spor Bilim. Araştırmaları Derg. 2022, 7, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychen, D.; Salganik, L.A. (Eds.) Holistic model of competence. In Key Competencies for a Successful Life and Well-Functioning Society; Hogrefe and Huber: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Matteson, M.L.; Anderson, L.; Boyden, C. “Soft skills”: A phrase in search of meaning. Portal-Libr. Acad. 2016, 16, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Institute for Gender Equality. Gender in Sport. 2017. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/publications/gender-sport (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- International Olympic Committee. IOC Gender Equality Review Project. 2017. Available online: https://stillmed.olympic.org/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/IOC/What-We-Do/Promote-Olympism/Women-And-Sport/Boxes%20CTA/IOC-Gender-Equality-Report-March-2018.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- International Olympic Committee. IOC Factsheet—Women in the Olympic Movement. 2021. Available online: https://stillmed.olympics.com/media/Documents/Olympic-Movement/Factsheets/Women-in-the-Olympic-Movement.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Galloway, B.J. The glass ceiling: Examining the advancement of women in the domain of athletic administration. McNair Sch. Res. J. 2012, 5, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Schaillée, H.; Derom, I.; Solenes, O.; Straume, S.; Burgess, B.; Jones, V.; Renfree, G. Gender inequality in sport: Perceptions and experiences of generation Z. Sport Educ. Soc. 2021, 26, 1011–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, M.G.; Grappendorf, H.; Wells, J.E.; Burton, L.J. Career Breakthroughs of Women in Intercollegiate Athletic Administration: What is the Role of Mentoring? Sport Innov. J. 2017, 10, 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinkins, L. Innovation Opportunities in Sport Management: Agile Business, Flash Teams, and Human-Centered Design. Sport Innov. J. 2021, 2, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication on a European Skills Agenda for Sustainable Competitiveness, Social Fairness and Resilience. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1223&langId=en (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. Skills, Gualifications and Jobs in the EU: The Making of a Perfect Match? 2015. Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/files/3072_en.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2023).

- Europass. Validation of Non-Formal and Informal Learning. 2023. Available online: https://europa.eu/europass/en/validation-non-formal-and-informal-learning (accessed on 22 March 2023).

| Occupation | ESCO Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Sport administrator | 1349.22 | Sport administrators act in a middle management role within sport organizations at all levels, in any sport or country in Europe (e.g., sport clubs, federations, and local authorities). They carry out organizational tasks across a wide range of functions in accordance with the strategy and policies set by management, boards of directors and committees. They play a crucial role in the overall delivery of sport and their work in sport organizations directly impact the unlocking of the potential of the sector in Europe towards health, social inclusion, and economy. |

| Sports, recreation and cultural center managers and Sport facility manager | 1431 and 1431.3 | Sports, recreation and cultural center managers plan, organize and control the operations of establishments that provide sporting, artistic, theatrical and other recreational and amenity services. Sport facility managers lead and manage a sport facility or venue, including its operations, programming, sales, promotion, health and safety, development, and staffing. They ensure it provides excellent customer service whilst achieving business, financial and operational targets. |

| Sports program coordinator | 2422.17 | Sports program coordinators coordinate sports and recreation activities and policy implementation. They develop new programs and aim to promote and implement them as well as ensure the maintenance of sports and recreation facilities. |

| Recreation policy officer | 2422.12.13 | Recreation policy officers research, analyze and develop policies in the sports and recreation sector and implement these policies to improve the sport and recreation system and improve the health of the population. They strive to increase the participation in sports, support athletes, enhance the performance of athletes in national and international competitions, improve social inclusion and community development. They work closely with partners, external organizations or other stakeholders and provide them with regular updates. |

| Main transversal skill set (n = 29) | Analytic/evaluation/control skills Business and entrepreneurship knowledge/experience Career awareness and planning skills Conflict management skills Creativity and innovation skills Cross-cultural competence Effective interpersonal communication skills (internal/external) Event management Finance and administration management Fundraising/funding opportunities Human resources management Leadership skills Legal and policy management Marketing knowledge Meetings management Networking Planning/organization/coordination skills Political skills Problem solving skills Research skills Risk management Safety/security/health management Stakeholders management Strategic management and ability to manage change Tasks and resources management Teamwork Technological and digital skills Volunteer management | |

| Ref. | Purpose | Sample | Sample Size | Gender | Methodology | Instruments/ Tools | Variables | MMAT Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [40] | To examine the brand creation process for international recurring sports events, using the FIS Cross-Country Alberta (Canada) World Cup 2008 and the FIS Cross-Country World Cup Drammen (Norway) 2008 as case studies | Key organizing committee members and event stakeholders | Key organizing committee members (n = 10) Event stakeholders (n = 5) | ND | Qual (triangulation strategy) | Semi-structured interviews (n = 15); Archival documents review (n = 46) | Key components in the branding process | 7 |

| [41] | To examine the perceived importance of skills and attributes for entry-level applicants to collegiate athletic departments during the hiring process | Directors (Athletic, Associate, Departmental) from Division I, II, and III | n = 315 (response rate: 15.2%) | Male (62%); Female (33%); ND = 5% | Quant | Online Quest. (20 closed-end items with a 1–5 pt. Likert Scale; One open-end question) | Rating of the importance of easily observable and not-readily observable skills, traits, abilities and other attributes | 7 |

| [42] | To enhance performance leadership and management in elite sport | Performance directors | n = 13 | Male (90%); Female (10%) | Qual | Semi-structured interviews | Recommendations, advices, and suggestions for other leaders, managers, and SOs to manage Olympic programs more effectively | 7 |

| [25] | To determine employers’ needs in the Australian SM job market and to evaluate occupational audit of SM positions | Job advertisements over a six-month period from different employment websites | n = 13 | NA | Mixed | Website screening | Keywords search (‘sport’ and ‘management’) in promotional, job descriptions, and publicly available working positions. Full and part-time employment data were collected and screened | 7 |

| [43] | To examine how collegiate athletic administrators consider job attributes when hiring for entry-level positions and the perceived skills and traits to succeed in this environment | Directors (Athletic, Associate, Departmental) from Division I, II, and III | n = 279 (response rate: 15.8%) | Male (60%); Female (40%) | Quant | Online survey (closed-ended items, 11 pt. scale) | Rating of profiles and 10 conjoint scenarios of both hypothetical job candidate or employee (attributes, and skills needed to succeed in the job) | 6 |

| [44] | To describe an experiential learning process that incorporates reflective learning within the context of a sport event management course and to investigate the relative learning outcomes | SM students (undergraduate) | n = 55 | ND | Qual | Reflective journal assignments and assessments (triangulation) | Students’ perceptions of the experiential learning process | 6 |

| [45] | To compare the perceptions of both sport club managers (self-perception) and coaches in relation to managers’ competencies | Sport club managers and coaches from 9 sport disciplines | n = 60 (response rate: 79%); (sport managers n = 30; coaches n = 30) | Male (71.5%); Female (28.5%) | Quant | Quest (closed-ended scaled items) | Rating of the importance and application of 25 competencies to manage effectively a sports club | 4 |

| [46] | To examine the career progression of NCAA Division I Athletic Directors (educational and career background) and their involvement in activities and functions within the athletic department. | Athletic Directors from Division I | n = 99 (response rate: 29.4%) | ND | Mixed | Online Quest (open-ended questions) and an adapted version of the Scale of Athletic Priorities | Educational information, career progression, professional experience, and the most rewarding and the most challenging aspects of their position; their involvement in duties and responsibilities | 4 |

| [47] | To analyze the relationship between communicational skills and barriers to individual creativity of personnel of a Department of Sports and Youth and Sport Boards | Board members | n = 174 (estimated response rate: 90%) | ND | Quant | Quest | Barton (1990) standard questionnaire for the assessment of communication skills; Pfeiffer (1990) standard questionnaire to assess barriers to individual creativity | 4 |

| [48] | To explore the attitudes and experiences of Sports Development and Sports Management students toward entrepreneurship education, highlighting best practice from a pedagogical perspective | SM students (undergraduate) | n = 122 | Male (49.2%); Female (50.8%) | Qual | Semi-structured interviews | Impact and value of entrepreneurship education upon attitudes, knowledge and career choices through introductory, follow-up and probing questions | 7 |

| [49] | To investigate the specific computer programs used by sport organization employees, the tasks they performed with those programs, and expectations regarding computer competencies SM graduates as job applicants should possess | Employees in different SOs | n = 35 (response rate: 82%) | Male (57%); Female (43%) | Qual | Semi-structured interviews | Specific computer programs used by participants, the tasks they were completing with these programs; insights into participants’ expectations with regard to the computer competencies a candidate for employment a graduate in SM should possess | 6 |

| [50] | To address the establishment of the competence indicators for sports business management professionals within the education programs in Asian higher education institutions (10 university departments) | Professors, chairmen, and class/program planners in sport business and management; experts and scholars from academia, government and industry. | n = 58 | ND | Mixed | Focus groups, interviews, online Quest. (44 closed-ended items, Likert-type scale 1–5 pt.) | Evaluation of six dimensions in relation to sport business professional competence indicators (professional knowledge, professional skills, communication, administration, work-related attitude and creativity) | 5 |

| [51] | To examine the skills of the Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) of professional sports clubs and to present and suggest an appropriate skills model for managers | Sport managers of professional sport clubs | n = 76 (response rate: 91.5%) | Male (77.6%); Female (22.4%) | Quant | Quest (19 closed-ended items Likert-type scale 1–5 pt.) | Assessment of the managerial skills (conceptual, human, technical, and political) | 4 |

| [52] | To examine the relationship between community SOs (CSO) and sponsors, in terms of critical elements of the relationship process and their perceived impact on important outcomes for those clubs | Presidents of CSOs (or their representative) | n = 250 (response rate: 42%) | ND | Quant | Online Quest (45 closed-ended items, Likert-type scale 1–7 pt.) | Perceptions of the CSO–sponsors relationship process and outcomes in relation to “operational competence” (capturing technical and conceptual skills), “dependability” (consistency and trust), “balance”, and “relational competence” (interpersonal skills) | 7 |

| [53] | To determine the competencies and training needs of secondary school sport managers in South Africa | School sport managers (only 5% as full-time employees as school sport managers) | n = 79 (response rate: 64%) | Male (75%); Female (25%) | Quant | Quest (closed-ended, scaled items) | Competencies perceived as important to manage school sport; to which extent participants perform these competencies; their perceived training needs in relation to specific SM competencies | 4 |

| [54] | To examine SM curricula to ensure a progression and evolution toward a superior level of student preparedness for their internship experiences | SM students; site supervisors | Students: n = 136 (survey: n = 100, response rate: 74%; focus groups: n = 59, response rate: 43%); Site supervisors: n = 82 (survey: response rate: 100%; feedbacks: n = 49; response rate: 60%) | Students: Male (75%); Female (25%); Site supervisors: Male (78%); Female (22%) | Mixed | Online survey (closed-ended items, Likert-type scale 1–5 pt.); Intern performance analysis; Focus groups; Site supervisor feedback | Survey: Five dimensions related to career preparation (general preparation, communication skills, critical thinking, technology, and leadership development and ethics). Written feedback from students for qualitative responses regarding their internship experiences. Focus groups: semi-structured questions to assess student’s perceptions regarding their academic path and internship experiences. Supervisors’ feedback related to how the SM program could better prepare interns and what specific skill areas students were lacking. | 4 |

| [55] | To examine the construction of competence through an analysis of leadership and management in AFL clubs, during a period of great change for the AFL (2003-2006), considering leadership and management competence as social and organizational constructions | Chief Executive Officers (CEO), presidents/chairs (president), and football managers from 16 AFL clubs | n = 38 | ND | Qual | Semi-structured interviews | Participants’ perceptions of their club: mission, organizational success, organizational structure, relations, commercial aspects, how organizational relationships were managed, decision making, key decision makers, and challenges faced. Perceptions regarding competencies, knowledge, and background experience required to be a manager and leader in an AFL club | 4 |

| [56] | To explore the manager of the pitch leadership role, utilizing semi-professional football in Ireland as the research setting | Managers, players and board members from four clubs | n = 11 (4 managers, 4 players and 3 board members) | Male (100%); Female (0%) | Qual | Interviews | Perceptions regarding the manager’s leadership role with players away from the coaching and in-game context, the manager’s interactions with the board, support staff, and the media | 5 |

| [57] | To investigate open innovation (i.e., the use of purposive inflows and outflows of knowledge to innovate) in the context of non-profit sports clubs | Board members of non-profit sport clubs | n = 11 | Male (73%); Female (27%) | Qual | Semi-structured interviews | Participants’ perceptions regarding the management of different aspects in their club (competition, cooperation, costumer integration, distribution of tasks, qualifications, commitment, organizational structure, infrastructure, financial situation), also in relation to innovation | 7 |

| [58] | To examine the mediation effects of leader–member exchange (LMX) in the relationships between political skill and four career-related outcomes (career satisfaction, perceived external marketability, life satisfaction, and perceived effectiveness) in SM | SM students (undergraduate) | n = 201 (response rate: 85%) | Male (70%); Female (30%) | Quant | Quest. (Modified versions of validated scales) | Assessment of six main domains corresponding to political skill, career satisfaction, perceived external marketability, life satisfaction and general life satisfaction, and perceived effectiveness | 5 |

| [59] | To examine Greek sport and recreation employers’ perceptions of employees’ skills needed in this industry, testing the applicability of the Greek version of Survey of Employability Skills Needed in the Workforce (SESNW, Robinson, 2006) | Employers in the sport sector (owners and/or general managers, executive or technical manager, P.E. counselor) | n = 193 (response rate: 60.7%) divided in four groups of employers | Male (72.5%); Female (27.5%) | Quant | Quest. (Greek version of the SESNW: 50 closed-ended items, Likert-type scale 1–5 pt.) | Employers’ expectations on graduates’ employability skills | 5 |

| [60] | To explore leadership competencies in non-profit SOs | Presidents of sports federations from 7 sport disciplines, department managers, board members, and Olympic coaches | n = 18 | Male (72%); Female (28%) | Qual | Semi-structured interviews | Perceived relevant leadership behaviors, competencies and capabilities in non-profit SOs | 6 |

| [61] | To explore skills, attributes, capabilities, and knowledge that a sports employer requires a SM graduate | Employers in the sport sector, sport industry professionals, and academic scholars | n = 21 | ND | Qual | Semi-structured interviews and written feedback | Perceptions of the most important knowledge and skills graduates should have and how university can develop them (i.e., employability skills and enterprise skills) | 5 |

| [62] | To explore the management competencies of Presidents of Brazilian Olympic Sport Federations (OSF) presenting different degrees of professionalization and how they operate | Presidents of Olympic Sport Federations | n = 10 | Male (90%); Female (10%) | Mixed | Online Quest. (Managers’ competencies (MBI): Lawrence et al., 2009); semi-structured interviews; Observations | Rating of real and ideal competencies; perceptions on management competencies; observations included visits to presidents’ federation offices and notes were taken about their communication behavior, staff dress code, workplace’s physical layout and other artefacts | 7 |

| [63] | To explore the positive and negative factors influencing transformational learning experiences of female leaders in women’s leadership development programs in sports | Sport managers from several SOs | n = 10 | Male (0%); Female (100%) | Qual | Semi-structured interviews (phone) | Participants’ perceptions and experiences regarding their participation in the leadership program | 4 |

| [64] | To determine the prominence of sales courses within SM curricula as well as industry perceptions of preferred qualifications | Colleges/universities and SM hiring managers | Colleges/ universities: n = 481; SM hiring managers: n = 10 | Male (100%); Female (0%) | Qual | Semi-structured interviews (phone and Skype) | Expectations for new hires in relation to: prior industry experience, educational degree; potential differences when considering education and prior industry experience in the hiring process; difference between a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree in SM when hiring; requisite skills to succeed as a sales representative; level of preparedness of graduates | 7 |

| [23] | To examine how specific patterns of competencies are associated with SM alumni’s occupational context | SM graduate students | n = 142 (response rate: 51%) | ND | Quant | Online survey | Four competency dimensions (Self-competency, Social competency, Methodological competency, SM competency) | 7 |

| [65] | To examine the curriculum posted on program websites of sales education in undergraduate SM programs | Institutional websites of universities; SM program directors, sales scholars, department chairs | n = 104 (response rate: 28.4%) | ND | Quant | Institutional website screening; Online survey | SM curricula screening for sport sales courses; survey to examine how sport sales courses are administered and the plans and perceptions of programs not offering a sport sales course yet | 7 |

| [66] | To apply “Europeanness” to the analysis of internationalization in the SM labor market and which changes this trend necessitates for SM curricula | SM professionals | n = 30 | Male (73%); Female (27%) | Qual | Semi-structured interviews | Open-ended questions related to main themes, trends, competencies, job development, and recruitment | 7 |

| [67] | To explore leadership within non-profit sport governance | Board members and Chief Executive Officers | n = 16 | ND | Qual | Interviews | Leadership style, skills and characteristics, the challenges of leading in a federally-based governance model, and the issue of shared leadership between the CEO and the board | 7 |

| [13] | To examine how international co-branding can be implemented as a strategic advantage in the development of SM programs to better prepare future practitioners for a growing international sport marketplace | Co-branded double degree program involving two universities; practitioners in the global sport industry | n = 68 | ND | Mixed | Program analysis; online survey | Qualitative data (i.e., program description, analysis of program in both universities, publicly available information about the institutions); online survey with practitioners in the global sport industry to obtain the views of professionals working in the sport industry about joint global SM programs | 7 |

| [68] | To holistically examine the decision-making process of SM students, including their motivations to enter the major and their career aspirations | SM students (undergraduate) | n = 47 | Male (47%); Female (53%) | Qual | Semi-structured interviews; focus groups (gender-segregated) | Factors related to the decision to enroll in SM education, perceptions and expectations related to the major, career aspirations, and industry perceptions | 7 |

| [69] | To examine the extent to which SM students address the individual and social dimensions of critical reflection during work-integrated learning (WIL) experiences and whether these skills align with what employers seek in the hiring process | Students, academic supervisors and industry supervisors from 20 universities | n = 288 (Industry Supervisors (n = 35), Academic Supervisors (n = 25), Students (n = 228)) | ND | Mixed | On-line semi-structured Quest. (37 closed-ended items, Likert-type scale 1–6 pt; open-ended questions) | Assessment of the individual and social dimension of critical reflection during WIL; perceptions regarding the need for critical reflection in SM graduates | 7 |

| [70] | To explore how to best prepare SM students to enter the field of sport communication, specifically using social media in college athletics | Professionals overseeing social media accounts for universityathletic departments | n = 4 | Male (100%); Female (0%) | Qual | Semi-structured interviews | Participants’ perceptions on the use of social media, skills sought in students, and how to educate students | 4 |

| [71] | To examine professional sport industry internship job postings in the United States by examining the content of online announcements | Internship postings from two designated online databases over a six-month period | n = 2 websites (215 unique internship announcements) | NA | Qual | Website screening | 24 variables to examine eachinternship job posting (descriptive information, administrative components, and transferrable skills) | 7 |

| [12] | To examine competencies needed in the sport industry and the proficiency of SM students (Erasmus project “New Age of SM Education in Europe”, NASME) | Experts from the field of SM in Germany; SM students | Experts: n = 54 (response rate: 54.4%); Students: n = 83 (response rate: 67%) | Experts: Male (81%); Female (19%); Students: Male (66%); Female (34%) | Quant | Semi-structured Quest (72 items) | Rating of competencies, skills and requirements (importance and proficiency). Competence areas: social, action, personal, marketing management, digital, general management, SM | 7 |

| [72] | To determine the importance of the knowledge of English as a foreign language, language skills, and knowledge of sports management-specific terminology | SM students (undergraduate) | n = 70 | Male (63%); Female (37%) | Quant | Quest. (57 closed-ended items, Likert-type scale | Assessment of basic language skills—reading, writing, listening and speaking—and the specific English vocabulary knowledge in relation to SM | 4 |

| [73] | To analyze the validity and reliability of Sports Managers Competency Scale (COSM) in the Chilean context | Municipal sport managers | n = 212 | Male (82.5%); Female (17.5%) | Quant | Quest. (Closed-ended items, Likert-type scale 1–5 pt.) | 31 management competencies, grouped into six dimensions: governance, sport foundations, budgeting, risk management, computer skills, and communication | 4 |

| [74] | To explore how SM students conceptualize diversity and inclusion | SM students (undergraduate) | n = 13 | Male (39%); Female (61%) | Qual | Semi-structured interviews (phone) | SM students’ conceptualization of diversity and inclusion, their holistic perspectives on the topic beyond the traditional focus on race and gender | 7 |

| [75] | To understand the influences of entrepreneurial orientation and passion for work on service quality and sporting performance in SOs | Managers of non-profit sport clubs | n = 199 | ND | Quant | Quest | Assessment of entrepreneurial orientation, passion for work, service quality, and sporting performance | 4 |

| [76] | To develop an industry–academia strategy to help undergraduate SM students enhance employability through practical experiential learning (PEL) in a specific sporting event | Students, professors and enterprise mentors (Taiwan Masters Golf Tournament) | Students: n = 65; Professors: n = 6; Enterprise mentors: n = 4 | ND | Mixed | In-depth interviews and Quest. survey | Perceptions of supervisors and students who participated in the event regarding PEL in sport industry and employability by performing the importance-performance analysis (IPA) | 5 |

| [77] | To introduce an innovative course on LinkedIn in an SM program through experiential learning, as a driver of students’ career development and professional interactions. To assess the learning outcomes, a new scale was developed and tested | SM students (undergraduate) | n = 90 (response rate: 82%) | Male (82%); Female (18%) | Quant | Quest. (LinkedIn’s Professional Development Potential SM Scale, Likert-type scale 1–5 pt.) | Assessment of students’ perceptions of LinkedIn as a tool to develop their professional profile and entrepreneurial attitudes as a SM operator | 7 |

| [22] | To test the suitability of a general managerial competency model for sport managers | Experts in the sport labor market (clubs—30%; federations—22%; public sector—29%; private sector—19%). | n = 557 | ND | Quant | Online Quest. (72 closed-ended items, Likert-type scale 1–5 pt.) | Rating of the perceived performance and importance of SM competencies | 5 |

| [78] | To explore servant leadership and leader effectiveness outcomes in sport administration and to examine if political skill plays a moderating role | Athletic directors and coaches | Athletic directors: n = 250; Head coaches: n = 809 | Male (75%); Female (25%) | Quant | Online Quest. (Political SkillInventory (PSI): 18 items, Likert-type scale 1–7 pt.; Servant Leadership Scale: 14-item Likert-type scale 1–7 pt.) | Athletic directors: Assessment of political skills (social astuteness, interpersonal influence, apparent sincerity, and networking). Head coaches: evaluation of theservant leadership behaviors of their school’s AD and leader effectiveness. Perceived affective organizational commitment and job satisfaction | 7 |

| [79] | To examine the experiences of students participating in service learning and travel abroad, to explore whether these experiences are useful to work internationally in sport | SM students (undergraduate) | n = 6 | Male (33%); Female (77%) | Qual | Journals; Focus groups | Personal experiences during the trip; focus groups (n = 2) after the trip to critically reflect upon the travel experiences | 4 |

| [80] | To examine the credentials and competency demands of the sport business labor market in the United States | Job advertisements in 2008 and 2018 | n = 613 (2008: n = 200; 2018: n = 413) | NA | Mixed | Website screening | Job postings for sport business positions categorized according to sector, organization size, and functional role | 7 |

| [81] | To identify an innovative solution to improve global SM learning, showing how institutions from different countries can collaborate virtually to provide students with practical international perspectives through an applied sport globalization project | SM students (undergraduate) | American students: n = 30; German students: n = 13 | ND | Qual | Prompts and narrative reflections | Learning experiences and evaluation of the international joint class project | 5 |

| [82] | To investigate the relationship between crisis management, decision-making styles, and self-confidence skills in decision making in sport managers | Sport managers | n = 226 | ND | Quant | Online Quest. (Crisis Management Scale; Melbourne Decision-Making Quest. I-II; Self-Confidence Scale) | Assessment of the crisis management skills, the self-esteem and decision-making styles, and the level of self-confidence | 5 |

| Assigned Cluster | Items (K/C/S) | Frequency of Occurrence (%) in the Included Studies (n = 48) | Presence in the ESCO Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| Background knowledge | Sport management education, qualifications, academic achievements | 19 | |

| Event management | 25 | Present | |

| Finance and administration | 44 | Present | |

| Human resources | 25 | Present | |

| Legal and sport policy | 23 | Present | |

| Marketing | 35 | Present | |

| Strategic management and change management | 33 | Present | |

| Competence | Analytical/evaluation/control skills | 33 | Present |

| Cross-cultural competence | 29 | Present | |

| Decision-making skills | 23 | ||

| Emotional and interpersonal intelligence | 10 | ||

| Facility/operations management | 31 | Present | |

| Fundraising and grant writing | 6 | Present | |

| Goal orientation/setting | 15 | ||

| Knowledge transfer to practice | 17 | ||

| Planning/organization/coordination skills | 31 | Present | |

| Practical intelligence | 2 | ||

| Problem solving | 35 | Present | |

| Risk management | 21 | Present | |

| Sponsorship management | 17 | ||

| Tasks and resources management | 25 | Present | |

| Transfer skills | 6 | ||

| Volunteer management | 6 | Present | |

| General experience | Managerial knowledge/experience | 35 | |

| Sport-specific knowledge/experience | 33 | ||

| General work-related experience | 17 | ||

| Business and entrepreneurship attitude | 31 | Present | |

| Hard skills | Communication skills (written/oral) | 48 | |

| Foreign languages | 13 | ||

| Information management/statistics | 17 | ||

| Project management | 15 | Present | |

| Research skills | 10 | Present | |

| Safety/security/health management | 13 | Present | |

| Technological/digital/social media skills | 46 | Present | |

| Personal Traits | Initiative/proactivity | 13 | |

| Learning (skills and will) | 19 | ||

| Maturity | 2 | ||

| Motivation/Enthusiasm/Passion | 21 | ||

| Personal attributes (generic) | 17 | ||

| Soft skills | Ability to deal with pressure/stress | 6 | |

| Accountability | 17 | ||

| Adaptability/flexibility skills | 23 | ||

| Appropriate working behavior/professionalism skills | 27 | ||

| Career awareness and planning skills | 15 | Present | |

| Conflict management skills | 13 | Present | |

| Creativity and innovation skills | 25 | Present | |

| Critical thinking skills | 33 | ||

| Effective interpersonal communication skills (internal/external) | 65 | Present | |

| Ethical commitment and behavior/integrity | 40 | ||

| Leadership skills | 54 | Present | |

| Meetings management | 8 | Present | |

| Networking | 44 | Present | |

| Personal/self-management | 19 | ||

| Political skills | 19 | Present | |

| Respect of hierarchies, role boundaries, and responsibilities | 15 | ||

| Responsibility | 15 | ||

| Social skills/People skills | 23 | ||

| Stakeholders management | 35 | Present | |

| Teamwork | 46 | Present | |

| Time management skills | 21 | ||

| Working autonomy skills | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guidotti, F.; Demarie, S.; Ciaccioni, S.; Capranica, L. Knowledge, Competencies, and Skills for a Sustainable Sport Management Growth: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7061. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097061

Guidotti F, Demarie S, Ciaccioni S, Capranica L. Knowledge, Competencies, and Skills for a Sustainable Sport Management Growth: A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2023; 15(9):7061. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097061

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuidotti, Flavia, Sabrina Demarie, Simone Ciaccioni, and Laura Capranica. 2023. "Knowledge, Competencies, and Skills for a Sustainable Sport Management Growth: A Systematic Review" Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7061. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097061

APA StyleGuidotti, F., Demarie, S., Ciaccioni, S., & Capranica, L. (2023). Knowledge, Competencies, and Skills for a Sustainable Sport Management Growth: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 15(9), 7061. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097061