The Playground for Radical Concepts: Learning from the Tussengebied

Abstract

1. Introduction: The Use of Spatial Concepts in the Metropolitan Planning

2. Theoretical Framework and Methods

3. Results: Learning from the Tussengebied

3.1. The Dutch Planning Context

3.2. The Tussengebied as a Playground for Radical Concepts

3.3. Patchwork Metropolis

3.4. Urbanized Landscape

3.5. Field Metropolis

4. Discussion: Toward a Novel View of the Tussengebied

4.1. Knowing What

4.2. Knowing How

4.3. Knowing What End

4.4. Doing

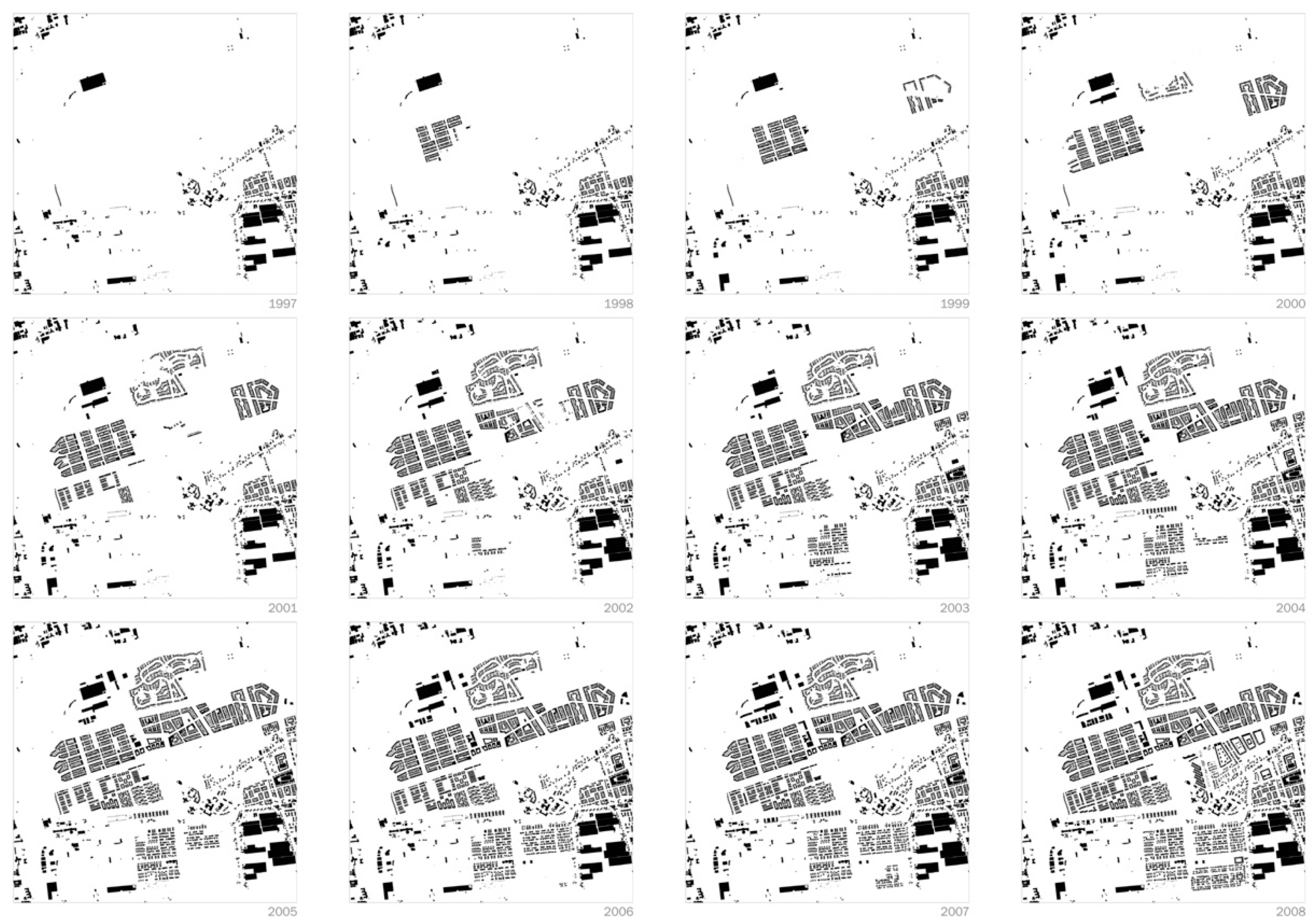

4.5. Ypenburg District

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Breheny, M.J. The Renaissance of Strategic Planning? Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1991, 18, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieverts, T. Cities without Cities: An Interpretation of the Zwischenstadt, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-0-415-27260-5. [Google Scholar]

- Albrechts, L. Planners as Catalysts and Initiators of Change. The New Structure Plan for Flanders. Eur. Plan. Stud. 1999, 7, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechts, L.; Healey, P.; Kunzmann, K.R. Strategic Spatial Planning and Regional Governance in Europe. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2003, 69, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies; Macmillan: London, UK, 1997; ISBN 978-0-333-49574-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gaeta, L.; Janin Rivolin, U.; Mazza, L. Governo del Territorio e Pianificazione Spaziale; CittàStudi: Turin, Italy, 2013; ISBN 978-88-2517-382-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, K.; Galland, D.; Harrison, J. (Eds.) Metropolitan Regions, Planning and Governance; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-25631-9. [Google Scholar]

- Balducci, A.; Curci, F.; Fedeli, V. Una galleria di ritratti dell’Italia post-metropolitana. Territorio 2016, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, A.; Raffini, L.; Alteri, L. Il Tramonto Della Città. La Metropoli Globale tra Nuovi Modelli Produttivi e Crisi Della Cittadinanza; DeriveApprodi: Roma, Italy, 2019; ISBN 978-88-6548-296-4. [Google Scholar]

- Corsi, S.; Sali, G.; Monaco, F.; Mazzocchi, C. The Cores of Metropolitan Areas: Evidence from Five European Contexts. TERRITORIO 2015, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N.; Pullano, T. Stato, Spazio, Urbanizzazione; Guerini Scientifica: Milan, Italy, 2016; ISBN 978-88-8107-404-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pisano, C. The Patchwork Metropolis: Between Patches, Fragments and Situations. In The Horizontal Metropolis Between Urbanism and Urbanization; Viganò, P., Cavalieri, C., Barcelloni Corte, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 93–100. ISBN 978-3-319-75975-3. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, L.; Poelman, H. Regional Typologies: A Compilation; European Union Regional Policy; European Union: Milan, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The State of European Cities Report—European Environment Agency. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/sustainability-transitions/urban-environment/links/data-and-information/the-state-of-european-cities-report (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Soja, E.W. Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory; Verso Books: London, UK, 2010; p. 228. ISBN 978-1-84467-669-9. [Google Scholar]

- Secchi, B.; Viganò, P. La ville Poreuse. Un Projet Pour le Grand Paris et la Métropole de L’après-Kyoto, 1st ed.; METISPRESSES: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; ISBN 978-2-940406-56-2. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, S. Points and Lines: Diagrams and Projects for the City; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-1-56898-155-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pisano, C.; Saddi, V. Open and Closed Figures in Dutch Spatial Planning. In Shaping Regional Futures: Designing and Visioning in Governance Rescaling; Lingua, V., Balz, V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 173–181. ISBN 978-3-030-23573-4. [Google Scholar]

- Meijsmans, N.; de Zwart, B. Towards a Culture of Regional Design. OASE-Territ 2009, 80, 108–125. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. The Treatment of Space and Place in the New Strategic Spatial Planning in Europe. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2004, 28, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettoretto, L.; Indovina, F. La Città Diffusa; DAEST—IUAV: Venice, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hertweck, F.; Marot, S. The City in the City. Berlin: A Green Archipelago; Lars Mueller Publishers: Zurich, Switzerland, 2013; ISBN 978-3-03778-326-9. [Google Scholar]

- Viganò, P.; Cavalieri, C.; Barcelloni Corte, M. (Eds.) The Horizontal Metropolis Between Urbanism and Urbanization; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-75974-6. [Google Scholar]

- Indovina, F. Dalla Città Diffusa All’arcipelago Metropolitano; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2009; ISBN 978-88-568-1170-4. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, F.R.; Jones, B.D. Agendas and Instability in American Politics, 2nd ed.; Chicago Studies in American Politics; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-226-03949-7. [Google Scholar]

- van Duinen, L. New Spatial Concepts Between Innovation and Lock-in: The Case of the Dutch Deltametropolis. Plan. Pract. Res. 2015, 30, 548–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, D. Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making; Revised ed.; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-393-97625-0. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.L. Institutional Analysis and the Role of Ideas in Political Economy. Theory Soc. 1998, 27, 377–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L. Ideas, Politics, and Public Policy. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2002, 28, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, M.A. Setting the Stage: A Dramaturgy of Policy Deliberation. Adm. Soc. 2005, 36, 624–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rein, M.; Laws, D. Controversy, Reframing and Reflection. In The Revival of Strategic Spatial Planning; Salet, W.G.M., Faludi, A., Eds.; KNAW: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dematteis, G. Progetto Implicito. Il Contributo Della Geografia Umana Alle Scienze del Territorio, 2nd ed.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2002; ISBN 978-88-204-9830-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pisano, C. L’uso di Spatial Concept nel progetto d’area vasta. Tre genealogie a confronto. CRIOS 2019, 18, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secchi, B. Isotropy vs Hierarchy. In Landscape of Urbanism; Ferrario, V., Sampieri, A., Viganò, P., Eds.; Officina Edizioni: Venezia, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Viganò, P.; Secchi, B.; Fabian, L. Water and Asphalt: The Project of Isotropy/Editors: Paola Viganò, Bernardo Secchi, Lorenzo Fabian; UFO (Amsterdam, Netherlands); Park Books: Zürich, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-906027-71-5. [Google Scholar]

- Guida, G. Immaginare Città. Metafore e Immagini per la Dispersione Insediativa, 1st ed.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2011; ISBN 978-88-568-3536-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P. The World Cities; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1971; ISBN 978-0-07-025600-2. [Google Scholar]

- van Assche, K.; Beunen, R.; Verweij, S. Comparative Planning Research, Learning, and Governance: The Benefits and Limitations of Learning Policy by Comparison. Urban Plan. 2020, 5, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, C.A.; Radaelli, C.M. Systematising Policy Learning: From Monolith to Dimensions. Polit. Stud. 2013, 61, 599–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, A.; Alvesson, M.; Kärreman, D. Critical Performativity: The Unfinished Business of Critical Management Studies. Hum. Relat. 2009, 62, 537–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.; Gibbons, J.D. Rank Correlation Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford Univ Pr: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-0-19-520837-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bogner, A.; Littig, B.; Menz, W. (Eds.) Interviewing Experts, 2009th ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-230-22019-5. [Google Scholar]

- Iriste, S.; Katane, I. Expertise as a Research Method in Education. Rural Environ. Educ. Personal. 2018, 11, 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Davoudi, S. Planning as Practice of Knowing. Plan. Theory 2015, 14, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. Epistemological Bricolage: How Practitioners Make Sense of Learning. Adm. Soc. 2007, 39, 476–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schon, D. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1984; ISBN 978-0-465-06878-4. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M.; Lee Ashcraft, K.; Thomas, R. Identity Matters: Reflections on the Construction of Identity Scholarship in Organization Studies. Organization 2008, 15, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hering, J.G. Do We Need “More Research” or Better Implementation through Knowledge Brokering? Sustain. Sci. 2016, 11, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackler, F. Knowledge, Knowledge Work and Organizations: An Overview and Interpretation. Organ. Stud. 1995, 16, 1021–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, C. Patchwork Metropolis. Un Modello Teorico per Il Progetto Dei Territori Contemporanei. Ph.D. Thesis, Università degli Studi di Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pellenbart, P.H.; Van Steen, P.J.M. Making Space, Sharing Space: The New Memorandum on Spatial Planning in the Netherlands. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En Soc. Geogr. 2001, 92, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander Wandl, D.I.; Nadin, V.; Zonneveld, W.; Rooij, R. Beyond Urban–Rural Classifications: Characterising and Mapping Territories-in-between across Europe. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 130, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Cammen, H.; de Klerk, L.A.; Dekker, G.; Witsen, P.P. The Selfmade Land: Culture and Evolution of Urban and Regional Planning in the Netherlands; Unieboek|Het Spectrum: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 978-90-491-0701-7. [Google Scholar]

- Needham, B.; Dekker, A. The Fourth Report on Physical Planning in the Netherlands. Neth. J. Hous. Environ. Res. 1988, 3, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, G.L. Greenheart Metropolis: Planning the Western Netherlands; Palgrave: Macmillan/London, UK, 1966; ISBN 978-1-349-81773-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lambregts, B.; Zonneveld, W. From Randstad to Deltametropolis: Changing Attitudes towards the Scattered Metropolis. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2004, 12, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, S.E.; Kemp, S.P. Integrating Social Science and Design Inquiry through Interdisciplinary Design Charrettes: An Approach to Participatory Community Problem Solving. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2006, 38, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balz, V.; Zonneveld, W. Regional Design in the Context of Fragmented Territorial Governance: South Wing Studio. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 23, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, T. Imagining Future Places: How Designs Co-Constitute What Is, and Thus Influence What Will Be. Plan. Theory 2011, 10, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, C. The Segmented Metropolis. The Tussengebied According to Neutelings, Palmboom and Alkemade. MONU 2017, 26, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Neutelings, W.J. Willem Jan Neutelings, Architect; Uitgeverij 010: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1991; ISBN 978-90-6450-120-3. [Google Scholar]

- Palmboom, F. Landschap en Verstedelijking Tussen Den Haag en Rotterdam; Stadsontwikkeling Gemeente: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1990; ISBN 978-90-72979-02-5. [Google Scholar]

- Delta Metropool. Available online: https://www.oma.com/projects/delta-metropool (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Pisano, C. Patchwork Metropolis. Progetto di Città Contemporanea; Lettera Ventidue edizioni: Siracusa, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Beelen, K. Imag(En)Ing the Real. The ‘Region’ as a Project of Cartographic Re-Configuration. In Designing for a Region; Uitgeverij SUN: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Palmboom, F. Rotterdam, Verstedelijkt Landschap. OASE 1987, 17, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Palmboom, F. Drawing the Ground Landscape Urbanism Today; Birkhuser Architecture: Basel, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dirk, S. Het Casco-Concept: Een Benaderingswijze Voor Landschapsplanning; NBLF: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Devolder, A.-M. Alexanderpolder: New Urban Frontiers; Laterza: Thoth, Egypt, 1993; ISBN 978-90-6868-074-4. [Google Scholar]

- Betsky, A. The New Land: The work of palmbout urban landscapes. In The New Land: The Work of Palmbout Urban Landscapes; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2012; pp. 29–32. ISBN 978-3-0346-1207-4. [Google Scholar]

- Secchi, B. Prima Lezione di Urbanistica, 15th ed.; Laterza Editore: Bari, Italy, 2000; ISBN 978-88-420-6060-4. [Google Scholar]

| Expert | Year | Spatial Concept | Commission |

|---|---|---|---|

| Willem Jan Neutelings | 1989 | Patchwork Metropolis | Commissioned by the Department of Housing Development of the Municipality of The Hague to study and design the area of the Zuidrand (Southern Edge) between The Hague and Delft |

| Palmbout—Frits Pamboom | 1990 | Urbanized Landscape | Developed as a theoretical study and then applied in the development plan for the Prinsenland (1987), a Rotterdam expansion area, and the Ypenburg masterplan (1993) in the Zuidrand (Southern Edge) between The Hague and Delft |

| Office for Metropolitan Architecture—Floris Alkemade | 2002 | Field Metropolis | A competition launched by the Dutch Rijksbouwmeester that followed the research of the Deltametropool Foundation, coordinated by Dirk Frieling, launched to study Randstad as a unique Metropolitan Region of 2800 km2 and almost 7 million inhabitants |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pisano, C. The Playground for Radical Concepts: Learning from the Tussengebied. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086958

Pisano C. The Playground for Radical Concepts: Learning from the Tussengebied. Sustainability. 2023; 15(8):6958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086958

Chicago/Turabian StylePisano, Carlo. 2023. "The Playground for Radical Concepts: Learning from the Tussengebied" Sustainability 15, no. 8: 6958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086958

APA StylePisano, C. (2023). The Playground for Radical Concepts: Learning from the Tussengebied. Sustainability, 15(8), 6958. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086958