Abstract

Small cities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia face the challenges of adequately providing for their citizens and maintaining and growing their population. This study of small cities in Saudi Arabia provides insights into the prevalent challenges faced by small cities from the perspective of a sample of experts in related fields. In this research, a self-completing online questionnaire was designed to gather valuable quantitative data on five critical themes drawn from relevant theoretical considerations, case studies of small cities, and official government documents. This study explores the issues of existing infrastructure, governance processes, relationships with other cities, current economic activity, and potential development opportunities. The findings suggest that the local urban governance and strategic planning of urban growth are among the main components of successful development in small cities, especially by providing local planning authorities with greater autonomy while considering the cities’ regional integration to form links with larger cities. As research in small cities in Saudi Arabia remains unexplored, the findings also highlight areas of further research which may lay the groundwork for future researchers and be utilized by policy makers to devise more effective policies and implementation strategies that render small cities more sustainable.

1. Introduction

Research on small cities has the potential to provide invaluable insights into a variety of fields, yet it remains largely overlooked by urban theorists [1]. From socioeconomic trends to public health and infrastructure, the study of small cities can offer essential perspectives on structure, function, and sustainability. Examining small cities can also provide perspectives on urbanism at large, as it allows for more detailed comparisons between different types of cities and a better understanding of their respective characteristics and effects. Through the collection of valuable data and insights, a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of urbanization can be gained, which can inform policy decisions and improve people’s lives.

This research focuses on small cities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Despite the massive growth in the Saudi population and extensive urbanization (as outlined in the literature review below), small cities continue to suffer a declining population, while large cities of over 1 million inhabitants continue to grow. This research seeks to gain a comprehensive understanding of the difficulties experienced by small cities in Saudi Arabia through the collection and analysis of expert opinions. The aims are to explore five critical themes (infrastructure, governance, relationships, economic activity, and development) and offer valuable insights to assist policy makers in formulating strategies that could lead to making small cities more sustainable.

Research on small cities in Saudi Arabia is of particular significance for understanding the dynamic and rapidly evolving socioeconomic landscape of the Kingdom. Exploring the intricate interrelationships between small cities and larger urban centers provides information on regional economic development and regional connections, as well as on how different populations can adapt to changing circumstances. As such, examining the smaller cities that make up Saudi Arabia will provide opportunities to develop better strategies to address issues related to urbanization, resource allocation, and governance in the years ahead.

1.1. Literature Review

Approximately 50% of the global urban population resides in urban areas with populations below 500,000 [2]. However, smaller urban settlements are rarely mentioned in mainstream discussions on urban studies, suggesting that smaller urban areas are often overlooked or ignored in the scholarly discourse on urbanization [3,4]. In fact, only a relatively small body of research exists that specifically focuses on small cities [1]. While several attempts have been made by researchers to theorize the world urban spectrum, small cities and towns continue to be left aside [3]. The development and environmental challenges faced by small cities in developing nations have received limited attention, despite their demographic significance at a global level [5]. These smaller urban areas have been largely neglected in discussions on developmental and environmental issues, indicating a gap in the research and understanding of their unique challenges [3,4,5].

Small cities are perceived as unique places with their own distinct histories, potential for agency, and specific environmental and political contexts. This highlights the need to recognize the diversity and complexity of small cities and to consider their individual characteristics and local contexts in research and analysis [5]. Numerous theorists have effectively advocated for the inclusion of small- and medium-sized cities in mainstream discussions within the field of urban studies [1,5,6]. Such efforts have helped to bring attention to the importance of these smaller urban areas in the scholarly discourse and highlight their significance in urban studies research [3]. It is imperative to examine the local practices, processes, identities, and autonomies of small cities and to develop a research agenda that specifically focuses on these unique urban areas. This underscores the importance of understanding the distinct characteristics and dynamics of small cities [1]. While there may be limitations to using quantitative data for researching small cities, such measures can still contribute to acknowledging the importance of small cities and the need for ongoing scholarly attention to better understand them [1]. Efforts should be made to explicitly identify the political, economic, social, cultural, spatial, and physical aspects that are relevant to small cities, both in isolation and as a collective. This approach can reveal practices and processes that have not been adequately addressed in urban theory thus far. By thoroughly examining these elements, we can gain deeper insights into the complexities of small cities and contribute to advancing our understanding of them in urban studies research [1].

This article sits within this context. Directing our focus towards the destinies and prospects of small cities may offer potential solutions to seemingly daunting challenges. This can aid in the formulation of a cohesive and critical research agenda for small cities that builds upon the existing progress made in the field. By actively exploring the opportunities and issues faced by small cities, we can make meaningful contributions towards advancing our understanding of these urban areas and addressing their unique challenges [1].

While it is important to consider larger urban frameworks, it is equally essential to examine the unique characteristics and dynamics of small cities in specific national contexts for a more comprehensive understanding [1]. Such an examination in a specific national context provides a more comprehensive understanding. This is the approach adopted in this article and contributes to a nuanced understanding of small cities and their place within the broader urban landscape of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

1.2. Urban Growth in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia is a rapidly urbanizing kingdom and has one of the highest levels of urbanization in the world [7]. Data from 1950 to 2015 show that there has been an exponential increase in urbanization from 21% to 83%, with eight out of ten people now living in cities [7], and it is expected to reach 90% by 2050 [8]. In 2017, the population of Saudi Arabia was heavily concentrated in three regions, Makkah (26%), Riyadh (25%), and Eastern Province (15%), which collectively accounted for 66% of the nation’s population [7]. Additionally, Saudi Arabia has one of the highest population growth rates in the world, reaching 34 million in 2020 [7]. For over four decades, Saudi Arabia has been faced with the problem of imbalances in resources, population, and activity distribution throughout its regions [8].

Since the late 1970s, the Saudi Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs (MoMRA) has led investigations into these demographic dynamics with the release of several documents on spatial national development [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. With the aim of promoting a more balanced development, numerous reviews and revisions have been released to reflect updated development priorities and future challenges for the Kingdom [8]. The most recent development is the National Spatial Strategy 2030 (NSS 2030) [14], which outlines a general approach to national urban policy, particularly in terms of defining investment priorities and fostering integrated urban and regional development in the most efficient manner. The NSS 2030 included topics such as natural resources, economy, industry and agriculture, social infrastructure, transportation, and physical infrastructure. Development corridors, growth centers, the administrative structure, and their spatial implications were also incorporated more recently [14]. The NSS 2030 shed light on the importance of small cities, stating that “medium and small cities and rural communities will form the basic building blocks for the development of regions of the Kingdom by best utilizing social and economic growth factors that have comparative advantages in these cities of the Kingdom” [14] (p. 5). The physical development of Saudi Arabia will be guided by this spatial strategy which aims to integrate the various regions and balance the population across the country.

In alignment with this goal, the NSS 2030 objectives have put a strong emphasis on economic growth, with the overall objective of achieving balanced regional development. Saudi authorities are faced with the dilemma of having to reconcile economic efficiency and social equity. The concentration of resources is needed for efficient economic development, while the diffusion of services is needed for equitable social outcomes. Therefore, the NSS must strive to find a balance between these two forces, all while striving for environmental sustainability. While Saudi citizens will continue to look for opportunities, the government must establish harmony rather than homogeneity [14].

1.3. Small Cities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

The United Nations Statistical Commission has endorsed a new method called the Degree of Urbanisation, which classifies cities into three size classes: 50,000–99,999, 100,000–499,999, and 500,000 or more inhabitants [15]. However, in Saudi Arabia, the Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs classifies cities into three different categories: (i) metropolises or large cities which have a population of more than one million inhabitants; (ii) secondary cities or medium cities with between 300,000 and one million inhabitants; and (iii) small cities with a population of fewer than 300,000 inhabitants [7]. Therefore, a combination of these two classification systems is used in this paper to define urban size small cities with a population of more than 50,000 and less than 300,000. Settlements with a population of less than 50,000 inhabitants are classified by the UN as towns and villages and are consequently not examined in this paper.

There are approximately 50 small cities scattered throughout the Kingdom, and they include Al Qunfudhah (on the Red Sea coast), Ar Rass and Unaizah (in the central region north of Riyadh), Gurayat (in the north near the border with Jordan), and Sharurah (near the southern border with Yemen). To safeguard against socio-economic disparity, the NSS 2030 aims to provide small towns and rural communities with the resources necessary for growing investment and development [14]. Specifically targeting regions with large clusters of small cities, such as Al Qasim in the center and Assir in the southwest, the aim is to promote opportunities for economic diversification and growth while fostering the necessary competitiveness in these areas. The population of small Saudi cities continues to fall, and this trend is expected to continue into the future [8,16].

Research into the growth of small cities highlights several key factors that impede their development. Among these, political influence, openness to trade, and inadequate transport networks connecting major cities with more rural areas were identified as substantial obstacles [17,18,19]. Moreover, Kanbur and Venables [20] suggested that the emergence of large metropolitan cities posed an additional issue, preventing other smaller cities from expanding and flourishing. Therefore, it is evident that policy interventions need to be implemented at all levels for small cities and rural areas to access their potential for sustainable development.

A review from the National Spatial Strategy [8] recognizes that the modernization of urban infrastructure in smaller cities increases their potential to take on larger populations, as well as improving economic activity. Diversifying the economic base by utilizing small cities also strengthens connections between urban and rural areas, ultimately leading to a higher rate of national economic growth in the long term. Additionally, the costs of upgrading infrastructure in small cities are comparatively affordable when compared with those required for major cities. Saudi authorities recognize that the provision of infrastructure and basic amenities such as water supply, waste management, healthcare, public transport, parks, businesses, and educational institutions are essential for any city’s development regardless of their size [8]. A selection of small (and medium size) cities have been designated as “growth centers”, with the presumption that they can handle population growth in the future [8]. These growth centers are targeted to absorb and manage population increases and attract migration from major cities. Additionally, the importance of improving the administrative and development structures of these smaller cities has also been highlighted [8,9].

1.4. Growing Cities and the Challenges of Economic Clusters

Economic theorists [21,22,23,24] have argued that cities are essential catalysts for economic development and growth. Cities are hubs of activity where economies of agglomeration, or economies that benefit from the concentration of multiple businesses and services within certain geographic areas, contribute to a higher level of productivity than what is observed in rural and village districts. This is largely attributed to larger labor pools, access to markets, increased competition, and a specialized labor force which contribute to improved efficiency. As a result, cities tend to attract a broad range of firms, industries, and people that can benefit from the efficiency gains available through concentration of resources. Researchers agree that urban agglomeration, which arises from the co-location of public and private organizations, is positively associated with economic development [18,25,26,27]. Furthermore, agglomeration in cities is advantageous for numerous reasons, including the spread of local knowledge, collective labor markets, increased energy efficiency, a diverse range of markets and products, access to financing opportunities, a unique culture specific to the area, improved human capital productivity, and infrastructure availability that incentivizes businesses to locate within such regions [28,29,30,31].

Evidence suggests that while cities in developed countries can be contributors to increased productivity and economic growth, this is not necessarily the case with cities in developing nations [31,32]. In their study on the effect of city size on economic growth in 113 countries between 1980 and 2010, Frick and Rodriguez-Pose [33] argued that this phenomenon mainly applies to developed regions. For instance, researchers [23,34,35] have suggested that the quality of urban infrastructure, institutional capacity, and industry availability are more important determinants of economic development in developing countries than city size. Moreover, placing too much emphasis on large cities could be detrimental to economic advancement at a national level in such countries if smaller and mid-sized cities are neglected.

1.5. Urban Governance of Small Cities

Centralization of power has been at odds with the development of small cities. However, delegating powers to local planning authorities has created a more balanced growth process between them and larger cities [36]. In response, the United Nations Economic and Social Council (UN ECOSOC) proposed an emphasis on local urban governance to promote sustainability. Facilitative factors such as strong leadership from local authorities, participation from stakeholders in finding viable solutions, collaboration between the public and private sectors, and policy objectives that are compatible between national and local planning authorities enable this governance [37,38]. Decentralized management that encourages involvement from the public and partnership building when making decisions is among the preferred methods of governance described by researchers [38,39,40].

It is essential to recognize that decentralization does not only suggest relinquishing power to local planning authorities but rather that it should lead to cooperative and collaborative efforts from stakeholders throughout the process of development [41], including the prioritization of efficient and sustainable partnerships [42]. In addition, these aspirations for decentralization require several guiding principles that include appropriate legislative powers, clear distribution of responsibilities, a long-term commitment to building co-ordination and capacity mechanisms, and adequate monetary resources allocated specifically for the growth of small cities [43,44,45].

In Saudi Arabia, for example, the lack of autonomy of local officials to set priorities and execute projects at the local level presents a critical issue regarding the organization of local planning authorities. While seemingly elaborate structures are in place that appear to indicate decentralization [7,8], the number and type of decisions made by national authorities suggest that the system remains highly centralized, creating a kind of “mirage effect” [46]. There is a need to implement a framework of legislation and administrative procedures to ensure proper and sustainable institutionalized urban governance [38]. This requires a combination of leadership from the top and greater autonomy from the bottom [47]. The Saudi government has stated plans to promote sustainable urbanism with the specific goals to “promote decentralization process and enhance municipal capacities” and “encourage privatization process and create incentives for local economic development through public and private partnership (PPP)” [8] (p. 67). Furthermore, one of the most pivotal issues in terms of governance is creating stronger communication links between government entities and with citizens and private organizations [7]. With the implementation of such objectives by all agencies and the private sector, as well as collaboration with UN-Habitat on the Future Saudi Cities program, sustainable urban governance could be significantly improved [38].

1.6. Relationships and Interconnections between Small Cities and Large Cities

It has been found that the features of urban systems vary when socio-economic circumstances shift [48,49]. This adaptation, however, is not isolated to a single city, as it also impacts cities in the vicinity. The changing environment causes all cities to adjust and reciprocally affect each other as they adapt to new conditions. Theorists have recognized the importance of inter-city communication and exchange in the development and growth of cities [50]. An urban system is fundamentally a regional unit consisting of locations influenced by social, economic, and functional bonds that are connected hierarchically [51]. The advancement in communication technologies hastens these changes, strengthens the interactions between cities within the region, and amplifies their scope [52,53]. Consequently, it is imperative to approach cities as an amalgamation of urban settlements as opposed to separated entities independent of other localities in their region.

Developed nations have thus far achieved some success in using regional interactions between cities as a major influence on the size and function of cities, largely due to conversations, exchanges, and networks between elements of the urban system such as residents, jobs, natural resources, services, and ideas [54]. Transportation and effective communication are also vital components in enforcing stronger links in terms of power, velocity, and efficiency between interdependent urban entities. Unfortunately, these fundamental components are what many developing countries lack and have impeded their progress. This is evident in how larger towns draw economic activities at the expense of small- and medium-sized cities; more isolated secondary cities have less propensity to grow with fewer appeals for economic investments [55,56].

To ensure balanced development and offset the concentration of economic activities and population in large cities, the Saudi government has deemed the need to reinforce connections between urban hubs and rural areas and increasing the capacities of small cities as essential. This is expected to not only create a more equitable hierarchy between cities, towns, and villages along a given development corridor laid out in the National Spatial Strategy, but also have a positive effect on regional growth [8].

1.7. Enhancing Sustainable Economic Development Opportunities in Small Cities

Small cities have recently experienced an increase in global attention, with many of them gaining recognition for their uncommon yet successful development stories [57]. This trend can be attributed to the unique approaches used by such cities to stimulate sustainable economic growth and diversify their economic base. These strategies can include, but are not limited to, investing in technological infrastructure, stimulating cross-sectoral collaboration and cooperation between different stakeholders, supporting local entrepreneurial initiatives, identifying new sources of income, and capitalizing on opportunities for tourism [57]. Small cities have the potential to foster significant economic development, making them an invaluable asset for any nation and worthy of the attention of policy makers [1]. This is illustrated in studies that point to the potential of smaller cities to generate unconventional growth [58]. Small cities may not only offer a unique set of characteristics, but they may also have access to more flexibility when it comes to infrastructure and resources, allowing them to enhance a wider array of opportunities to advance development.

Furthermore, small cities in many countries have seen a marked increase in economic, social, and cultural activities [59]. This has been attributed to their ability to capitalize on the spatial advantages afforded by their proximity to larger metropolitan centers, while also offering sought-after amenities due to their own embeddedness within regional networks [60,61,62]. Many small cities are successfully leveraging these advantages to become regional centers for employment opportunities or other positive contributing factors [63].

Rather than relying solely on financial contributions from the government, small cities have the potential to benefit from a variety of methods for sustainable growth, such as industrial specialization and investment in cultural and tourism activities [34,64,65,66]. These measures can be incredibly effective in boosting local economies, stimulating economic diversification, and ultimately paving the way towards a more vibrant and sustainable future.

Small cities engaging in such strategies often demonstrate a distinct approach to economic growth compared to metropolitan centers [67], and the positive repercussions brought about by their success can be felt significantly on a regional scale [59]. This approach encourages the decentralization of economic activity, allowing small cities to enjoy the benefits that come with mastering self-governance. These include increased capacity for local decision making, improved infrastructure and public services, diversification of the economy, a better quality of life for citizens, stronger connections to regional networks and institutions, enhanced competitiveness on a global level, and higher regional economic resilience [67,68]. Furthermore, creating successful small cities can provide an opportunity for larger metropolises to learn from these success stories in terms of how local policies can be adapted to achieve similar outcomes [59].

The Saudi government has been encouraged to sustainably manage the economic growth of small cities. It has acknowledged the necessity of boosting the capabilities of local planning authorities through decentralization, which would allow municipalities to undertake a number of responsibilities under the supervision of the Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs [8]. The Kingdom has been investing heavily in local municipalities in collaboration with the private sector in order to upgrade urban infrastructure and provide better services and municipal facilities, as well as to bolster the capability of local government officials [8]. This helps to enhance the capacity of small cities to attract investment, employment opportunities, and people, thus stimulating the local, regional, and national economy. The government has also been promoting the development of universities, research centers, medical facilities, and other educational establishments throughout the country to stimulate development in local areas.

This review of the pertinent literature and government documentation serves as a framework for the investigation pursued in this study, giving rise to its research themes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

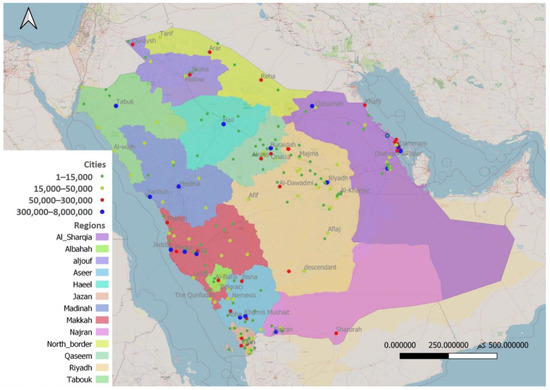

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is in the Middle East, bordering the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea. It is a large country that spans approximately two million square kilometers with an extremely diverse terrain, ranging from mountains and valleys to desert plains, making Saudi Arabia one of the most geographically varied Middle Eastern countries (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of Saudi Arabia showing cities and regions.

Within the dynamic and diverse urban context of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, this study focuses on the research question: what are the challenges facing small cities in Saudi Arabia and how can these challenges be met?

2.2. Research Method

The purpose of this research is to provide insight into the prevalent challenges facing small cities in Saudi Arabia from the perspective of a sample of experts in related fields. A review of the relevant literature informed this multi-lens approach, drawing from theoretical considerations, case studies of small cities, and official government documents. This research method focused on five critical themes drawn from the literature as having a substantial impact on the sustainability of small cities in Saudi Arabia: (i) existing infrastructure [8,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]; (ii) urban governance and administration procedures [36,37,38]; (iii) relationships with other cities [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]; (iv) current economic activity [18,23,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]; and (v) potential development opportunities [57,58,59,64,65,66]. By exploring these five components in unison, it was possible to gain a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of the current experts’ perception of small cities in Saudi Arabia, while considering the contributing factors which may shape their future growth.

Adhering to recognized quality and validity criteria [69], a self-completing online questionnaire was carefully designed on Google Forms with the aim of gathering valuable quantitative data on these five themes. The questions were rated on a five-point Likert scale: strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree. The survey consisted of twenty-eight items in six sections (Table 1).

Table 1.

Breakdown of survey sections.

2.3. Data Collection

This research collected responses from experts in urban planning and related fields. The sampling frame consisted of members of two professional databases (the Saudi Council of Engineers and the Saudi Urban Sciences Association). This list of approximately 1000 members was then filtered for more than 3 years of experience to about 700 members. This number was further reduced to around 500 by only including those holding an active license. This target group of 500 was sent a digital invitation (on WhatsApp) on 7 March 2022, explaining the purpose of the investigation and its objectives with a link to the survey on Google forms. On 22 March 2022, when 100 surveys were completed, the survey was closed as a typical response rate of 20% was achieved [69].

2.4. Data Analysis

The data analysis started with the calculation of the weighted means and standard deviation. Then, the Cronbach’s Alpha score was calculated to be 0.9348, indicating the survey was a reliable and consistent measuring instrument. To achieve the objective of simply identifying patterns and trends in the data obtained, only a percentage analysis of survey responses is presented, and these were then compared to understand their relative significance. This was deemed an appropriate tool to facilitate insight into the survey items [69]. Scores for “strongly agree/agree” and “strongly disagree/disagree” were frequently combined in this data analysis to reveal a proportional level of agreement as required for the purpose of this study.

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the key findings that address the research question and discusses the implications of these results. It is important to note that careful consideration should be given to any conclusions drawn, as well as actions taken based on the results. The findings need to be contextualized within any existing qualitative or quantitative data that have been collected to gain a fuller understanding of their significance.

3.1. Sample of Experts

The respondents were highly educated, with 56% holding post-graduate degrees (Master’s or PhDs) and 37% holding a Bachelor’s degree. They were also highly experienced in their profession, with half of the respondents having more than 20 years of experience in their field and only 5% with less than 5 years working experience. Most respondents (67%) worked in the government sector, with almost a third (27%) coming from the private sector. Respondents came from five areas of specialization (Table 2).

Table 2.

Breakdown of sample areas of specialization.

3.2. Assessment of Small City Infrastructure

The data indicate that the areas of electricity, water, education, health, roads and traffic control, and parks and recreation were ranked favorably. In each case, the majority of respondents agreed that these services were “well available” in small cities. However, public transport and sewage services saw most respondents indicating the neutral or disagree end of the scale (61% and 68%, respectively).

These results in relation to public transport and sewage services suggest that they do not adequately meet the needs of citizens. Currently, none of Saudi’s cities (big or small) provide public transport beyond basic bus networks (except for the recently completed railway in Makkah and the forthcoming Riyadh metro) [7]. It is imperative that investment be made in services lacking in small cities, as they are essential to ensure the well-being and quality of life of citizens. In terms of sewage facilities, by 2025, the government of Saudi Arabia aspires to achieve 100% coverage of sewage collection and treatment in cities with a population above 5000, with the intention to utilize the generated wastewater [7]. Investment in infrastructure for small cities can have many positive implications, including an increase in public opinion regarding the quality of small city lifestyle within these communities and the encouragement of new residents to relocate and boost population growth. Such investments can also lead to improved access to resources and services, such as health care and education, which could further support economic development. Ultimately, these benefits show that investment in infrastructure is essential for the sustainability of small cities.

The Saudi government has extensively documented its commitment to improving the quality of life of citizens [8,9,10,12,13], including dedicated initiatives for infrastructure and transportation [70]. Further study is needed to understand the specific issues surrounding essential services in small cities, for example, sewage and public transport provisions, followed by a deeper investigation of strategies to facilitate their improvement.

3.3. Perception of Economic Activities of Small Cities

Three questions asked respondents to indicate to what extent they agree with small cities’ ability to positively attract economic activities. The three variables were defined as: (i) primary economy based on local resources and skills; (ii) secondary economy based on manufacturing and production; and (iii) a tertiary economy based on trade and the provision of services.

These data on economic activities (Table 3) in small cities provide some interesting results. Primary economic activities seem to garner the most support, as 33% agreed that small cities are attracting such activities, and only 26% disagreed. However, the largest proportion remained neutral (40%), suggesting uncertainty or not knowing about this variable.

Table 3.

Small cities’ ability to attract economic activities.

Secondary economic activities had less support, as only 24% agreed and 39% disagreed. Although more respondents agreed when it comes to tertiary economic activities (35%), there was still a considerable proportion (30%) who opposed the idea, indicating a degree of discord surrounding this issue. The large number of neutral responses (35%) further suggests that there is an overall uncertainty among our experts as to how best to approach this issue.

Secondary and tertiary economic activities play a key role in the development of small cities. Investment in such activities can create jobs, improve infrastructure, promote overall economic growth, and improve quality of life. It can also drive innovation and entrepreneurship, which can often be lacking in more rural areas due to a lack of resources. Furthermore, secondary and tertiary economic activities are often vital for allowing these communities to gain access to larger markets, allowing them greater opportunities for trading goods and services with the outside world and ultimately providing necessary support that is essential for the sustainability of these small cities. National policies and funding play an important role in the development of small cities and regional areas. As outlined in the literature review, the Saudi government has clear intentions to develop the national economy, with several initiatives in place. However, the practicalities of implementing such plans to have a real impact remain elusive. Ultimately, additional research is required to gain a better understanding of small cities’ ability to attract secondary and tertiary economic activity and the necessary national and local policies required.

3.4. Urban Governance and Relationships

An investigation into the management of small cities in Saudi Arabia revealed a lack of autonomy in governance, with 42% of them perceived to be managed centrally by larger nearby cities, 41% subject to a combination of centralized and local decision-making, and only 6% being highly self-governing.

This research also aimed to explore the connection between existing local urban governance style and development potential. Most respondents (58%) agreed that the current management practices of small cities impact their ability to develop further. Only 8% did not agree with this statement, while a third were neutral.

The results support the notion that a major factor that hinders the development of small cities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is the concentration of management at the national level, leading to a disproportionate growth between major urban centers and other less developed areas. It is paramount that local authorities are given more autonomy to achieve sustainability [41], while concurrently engaging stakeholders at all levels of development and adhering to the aims of national policy [42]. To adequately support decentralization, there must be sufficient financial resources allocated to smaller cities and a qualitative advantage must be given to small- and medium-sized urban areas. Sound policies appear to be in place in the Kingdom [7,8] and the future of small cities looks promising if a comprehensive implementation process can be successfully applied.

The results also show an intriguing, yet unsurprising, view of the relationships between smaller cities and their larger neighboring cities. Almost a third of the respondents (27%) see the relationship as one of competition, with bigger cities competing for development and investments. Meanwhile, only 18% perceive the cities to be complementary to each other, suggesting that collaboration is occurring instead of rivalry. Furthermore, 43% of the respondents indicated that there is little connection between cities, indicating that each small city is its own entity with limited access to nearby resources and opportunities. When further exploring the relationship between small and large cities, respondents were asked if it had a negative effect on the growth of smaller cities. While 65% of participants agreed that this was the case, 25% were neutral and only 10% disagreed.

In response to the open-ended question about how small and big cities should interact, a coding analysis of responses suggested that respondents preferred a mutually beneficial connection between the two. Comments from the sample included advocating for an integrated connection between cities to drive small city growth, mutually beneficial relationships where economic activities are distributed throughout the region, complementarity that would foster small city growth and make them development hubs, complete infrastructure, and equity in all areas of development.

Several respondents suggested integrating resources and services to improve small cities’ quality of life, as well as strengthening their reputation to draw in investment. Likewise, there was a shared sentiment that small cities ought to have their own identity based on distinctive economic activities such as education and recreation; this may result in a more attractive lifestyle that is different from other cities, providing services without large city pollution or congestion at more affordable prices.

Research has demonstrated that cities are not independent entities but rather thrive as part of an interconnected network with other cities [50,51]. This is where an effective urban system helps to create connections between cities and communities and is an important factor that affects the growth and wellbeing of small cities, allowing them to be productive, profitable, and appealing by encouraging networks within regions. Such an interconnected system helps cities to access resources more efficiently and can drive innovation, creativity, and collaboration. It also helps create healthy competition between cities as they strive for prosperity and sustainability.

The Saudi government has identified the importance of strengthening the links between large cities and rural areas, as well as augmenting the resources of smaller cities in regional areas [8,9]. While this approach is designed to create a fairer balance between urban centers, towns, and villages within a given development framework, further research is necessary to ascertain a full exploration and understanding of the issue so that potential solutions and interventions can be implemented effectively.

3.5. Potential for Development

This final section of results suggests that small cities possess vast potential for development that is yet to be realized. Five questions investigated the level of existing and potential development in small cities.

Firstly, out of the sample surveyed, approximately half (49%) considered small cities to have satisfactory levels of development, with 38% perceiving them as weak or very weak and only 13% considering them to be at a strong level. This suggests significant variation in the perceived level of development between small cities, necessitating further research to identify the most effective strategies and policies for promoting growth and prosperity among small cities.

Secondly, the findings indicate a shared consensus on three aspects of advancing the progress of small cities: increasing infrastructure efficiency, forming legislation to connect cities, and offering an advantage to foster infrastructural advancement and inter-city integration (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors contributing to potential development of small cities in Saudi Arabia.

Small cities face many challenges as they try to capitalize on opportunities for growth and development. These challenges require efficient, connected infrastructure to better equip them for success. To create this, policy makers should consider implementing legislation to connect cities and provide the competitive advantage needed to build robust infrastructures and foster integration between different cities. This finding shows a consensus on the importance of these three factors, demonstrating the need for further exploration of effective strategies to ensure that small cities have access to successful and sustainable development.

Finally, the questionnaire concluded with an open question (59% responses), seeking opinions on how a competitive advantage could be created for small cities to enhance development. A discussion of the emergent patterns derived from summarizing the coding analysis follows.

Policy makers must provide investment opportunities that include employment, education, infrastructure, resources, and tourism, as they are essential for the development of small cities. Facilitating legal and financial procedures to stimulate the establishment of companies provides government stimulus, which may include tax exemptions and reduced fees, as well as incentives for entrepreneurs. Investing in infrastructure and services for small cities can provide financial incentives for potential investors and businesses, leading to increased economic activity. This boost in the local economy encourages sustainable growth, as well as employment and educational opportunities. Having these available also helps attract more people to settle in small cities, creating an even healthier economy. It is essential to have access to these kinds of opportunities to ensure that small cities not only survive, but also advance and prosper.

Small cities have the potential to become more competitive through initiatives such as government support for strong economy for each small region or city. This initiative would encourage investment in geographical, natural, cultural, social, and economic characteristics, providing opportunities for “competitive development”. This consequently can lead to the growth of cities and their attractiveness to investors or entrepreneurs. Such initiatives have the potential to create an environment that facilitates innovation and progress and forms an attractive location for investment or enterprises.

Decentralizing government processes and giving local planning authorities more power can be beneficial for future development. This includes expanding the scope and responsibilities of such authorities, enabling and activating the role of local administration, and involving the local population in formulating future development directions. Doing so encourages independent local planning while providing residents with a role in the initiative, innovation, and cooperation instead of centralized top-down control that hinders the establishment of local capacities. Such an approach has the potential to create more sustainable economic environments, which will benefit small cities in both the short and long term.

To make small cities more competitive, it is essential for policy makers to establish, improve, and enable infrastructure and services for existing residents as well as attract new residents to enjoy the features of living in a small city. Thoughtful regional and urban planning not only helps small cities grow sustainably but also creates job and educational opportunities that attract people from outside the area. By investing in infrastructure, a city can become attractive to potential investors, entrepreneurs, and other businesses, leading to increased economic activity and population.

To achieve competitiveness and ensure sustainable development, small cities must investigate and construct an individual set of strategies and acts that are suitable for their own circumstances and distinct from other cities. There is no one action, strategy, or policy that can be applied universally. As Thrift asserts, “one size does not fit all” [71]. Instead, the most crucial obstacle is generating a unique value proposition and fashioning a strategy that sets each small city apart from others [72]. Nevertheless, various strategies and initiatives to create a competitive advantage for small cities and enhance development have been used by governments in both developed and developing countries. For example, in recent decades, Korea has accomplished remarkable economic and social development for shrinking small cities and achieved improvements in promoting the devolution of centralized government to local authorities, balancing land development, and deconcentrating economic activities [73]. Korea’s central government has carried out extensive plans to encourage more balanced development throughout the nation. The intention is to promote growth in all areas of the country to diminish stress in the capital region and uplift rural locations. Similarly, Japan’s “One Village One Product” is a successful example of the government’s many official development assistance projects to promote rural development and enhance the growth and sustainability of small cities and towns [74]. Finally, to supply infrastructure development and job openings in small cities by lowering migration to big cities and fostering the advancement of surrounding country areas, India has been successful in establishing economic opportunities and upgrading infrastructure in many small cities across the country [75]. These are just a few examples of national government strategies that have successfully created a competitive advantage for small cities to enhance their development. By investing in key industries, promoting unique local products, and developing infrastructure, Saudi’s national government can help small cities to thrive and become more competitive in the global economy.

4. Conclusions

This study addressed the issues confronting the growth of small cities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, as well as strategies to promote their development. The findings support the consensus in the literature that small cities are vital to the national economy, face distinctive challenges, and deserve special attention. It has been demonstrated that the local urban governance and strategic planning of urban growth are among the main components in the successful development of smaller cities in the Kingdom, especially by providing local small city planning authorities with greater autonomy, while considering their regional integration to form links with larger cities.

The sustainability of small cities depends largely on the effective management of urbanization efforts. Small cities in Saudi Arabia are facing big challenges to adequately provide for their citizens and maintain and grow their population. Thus, it is essential that policy makers adhere to a comprehensive and integrated approach toward creating a balance between large and small cities and facilitating access to greater quality of life for all inhabitants, while simultaneously reinforcing ties between rural and urban regions and taking advantage of economic, environmental, and social connections between them.

It is essential to identify the strengths and competitive edge of small cities, as well as to establish a distinct identity through their spatial, historic, cultural, and human traits. This helps these cities improve their economic functions, providing citizens with greater stability and financial impacts at the national level. In addition, developing comprehensive regional and urban plans that promote sustainable development can help these cities achieve long-term growth, as has been demonstrated successfully in other countries such as Korea, Japan, and India. Saudi Arabia has committed policies and programs to provide greater economic opportunities for small cities, including improved infrastructure, job opportunities, and decentralized management that can potentially help to build more sustainable communities that are connected, prosperous, and more evenly populated. However, the implementation of these goals remains elusive.

Small cities in the Kingdom remain an understudied area, limiting our ability to understand their local complexities and nuances. While this study is unique in its focus on small cities in Saudi Arabia and opens the door to further research and discussion, it is limited to only general perceptions of a sample of experts and the analysis provided is limited in scope. A more detailed study of small cities in Saudi Arabia is recommended that may include residents and decision makers in the sample and ensure representation from all regions of the Kingdom. A detailed case study on one or comparative small cities is also recommended, as is the development of a framework for future analysis of small cities in Saudi or the wider Gulf region. Furthermore, a comparison of responses across the regions of Saudi Arabia is also deemed useful, in addition to comparisons across different groups of respondents. Local urban governance and relationships between cities is another area that requires further in-depth research to identify the essential connections among various stakeholders that will likely impact the future economic, social, political, and environmental conditions of the region. It is necessary to determine how the city can stand out, its economic role and relationship within the region, the areas where it can establish a competitive advantage, and the critical factors of the business environment that will determine success when compared to other cities. Such research could provide valuable insights in terms of how small cities in the Kingdom can provide a unique combination of strengths to enhance their future sustainable development. Further detailed analysis of the state of small cities could also serve as a stimulus for new ideas and approaches that could help authorities in different sectors formulate strategies better suited to small cities while providing evidence-based policy solutions grounded in realistic contexts. Increasing the collective understanding about how best to respond to these challenges in urbanization, while also analyzing the transferability of successful strategies in other contexts, would also help determine the best practices that can be implemented to build and connect sustainable small cities throughout the Kingdom.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A. and F.A.; methodology, S.A. and F.A.; validation, S.A. and F.A.; formal analysis, S.A. and F.A.; investigation, S.A. and F.A.; resources, S.A. and F.A.; data curation, S.A. and F.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.; writing—review and editing, F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from the Ministry of Education, Saudi Arabia through the project no. IFKSURG-2-1000.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the fact that is it non-interventional and non-experimental; the institution does not consider ethical approval a compulsory requirement for such studies.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research and Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project no. IFKSURG-2-1000.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bell, D.; Jayne, M. Small cities? Towards a research agenda. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guin, D. Contemporary perspectives of small towns in India: A review. Habitat Int. 2019, 86, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servillo, L.; Atkinson, R.; Hamdouch, A. Small and medium-sized towns in Europe: Conceptual, methodological and policy issues. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2017, 108, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véron, R. Small cities, neoliberal governance and sustainable development in the global south: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Sustainability 2010, 2, 2833–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacour, C.; Puissant, S. Re-urbanity: Urbanising the rural and ruralising the urban. Environ. Plan. A 2007, 39, 728–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori-Amoah, B. Beyond the Metropolis: Urban Geography as If Small Cities Mattered; University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Cities Report. Future Saudi Cities Programme; Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2019.

- UN Habitat. Review National Spatial Strategy; UN Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UN Habitat. Review of Regional Planning in Saudi Arabia; UN Habitat, Future Saudi Cities Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Future Saudi Cities Towards a New Agenda. Available online: https://saudiarabia.un.org/en/download/6304/31247 (accessed on 13 December 2022.).

- Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs. Atlas of Urban Boundaries for Saudi Cities; Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 1989.

- Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs, Deputy Ministry for Town Planning. Demographic, Transportation, Land Use and Economic Studies; Technical Report; SCET International/SEDES: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 1987.

- Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs. The National Spatial Strategy; Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2001.

- National Spatial Strategy. The Policy for National Spatial Strategy 2030 (White Paper); Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2018.

- United Nations Statical Commission. A Recommendation on the Method to Delineate Cities, Urban and Rural Areas for International Statistical Comparisons (Rep.). 2020. United Nations. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/51st-session/documents/BG-Item3j-Recommendation-E.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision; Online Edition; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ades, A.F.; Glaeser, E.L. Trade and circuses: Explaining urban giants. Q. J. Econ. 1995, 110, 195–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duranton, G. From cities to productivity and growth in developing countries. Can. J. Econ./Rev. Can. d’Économique 2008, 41, 689–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puga, D. Urbanization patterns: European versus less developed countries. J. Reg. Sci. 1998, 38, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbur, R.; Venables, A.J. (Eds.) Spatial Inequality and Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Glaeser, E.L.; HKallal, D.; Scheinkman, J.A.; Shleifer, A. Growth in cities. J. Political Econ. 1992, 100, 1126–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Development Report 2009. Reshaping Economic Geography; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Glaeser, E.L. A world of cities: The causes and consequences of urbanization in poorer countries. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2014, 12, 1154–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, P.C.; Graham, D.J.; Levinson, D.; Aarabi, S. Agglomeration, accessibility and productivity: Evidence for large metropolitan areas in the US. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feld, B. Startup Communities: Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Your City; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg, D. The Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Strategy as a New Paradigm for Economic Policy: Principles for Cultivating Entrepreneurship; Institute of International European Affairs: Dublin, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Economies of Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Plaziak, M.; Szymańska, A.I. Role of modern factors in the process of choosing a location of an enterprise. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 120, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakely, E.J.; Bradshaw, T.K. Planning Local Economic Development: Theory and Practice, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.D.; Rasker, R. The role of economic and quality of life values in rural business location. J. Rural. Stud. 1995, 11, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, P.; Acs, Z.J. Globalization: Countries, cities and multinationals. Reg. Stud. 2011, 45, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision. 2014. Available online: http://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/ (accessed on 15 August 2015).

- Frick, S.A.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Big or small cities? On city size and economic growth. Growth Chang. 2018, 49, 4–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camagni, R.; Capello, R.; Caragliu, A. The rise of second-rank cities: What role for agglomeration economies? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells-Quintana, D. Malthus living in a slum: Urban concentration, infrastructure and economic growth. J. Urban Econ. 2017, 98, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B. Urban Growth in Developing Countries: A Review of Current Trends and a Caution Regarding Existing Forecasts. World Dev. 2004, 32, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Economic and Social Council. Effective governance, policymaking and planning for sustainable urbanization. In Report of the Secretary-General; United Nations Economic and Social Council: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aina, Y.A.; Wafer, A.; Ahmed, F.; Alshuwaikhat, H.M. Top-down sustainable urban development? Urban governance transformation in Saudi Arabia. Cities 2019, 90, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharia, P. Autonomy and decentralization-current priorities in the local public administration management. USV Ann. Econ. Public Adm. 2012, 11, 288–292. [Google Scholar]

- Maghsoudi, R.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Effective Participation and Sustainable Urban Development: Application of City Development Strategies Approach. In Resilient and Responsible Smart Cities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Biermann, F.; Abbott, K.; Andresen, S.; Bäckstrand, K.; Bernstein, S.; Betsill, M.M.; Bulkeley, H.; Cashore, B.; Clapp, J.; Folke, C. Navigating the Anthropocene: Improving earth system governance. Science 2012, 335, 1306–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeng-Odoom, F. On the origin, meaning, and evaluation of urban governance. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr.-Nor. J. Geogr. 2012, 66, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Handbook for Policy-Makers, OECD Multi-Level Governance Studies OMD Work; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019.

- Allain-Dupré, D. Assigning Responsibilities Across Levels of Government: Trends, Challenges and Guidelines for Policy-Makers; OECD: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Essien, E. Impacts of Governance toward Sustainable Urbanization in a Midsized City: A Case Study of Uyo, Nigeria. Land 2021, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkadry, M.G. Saudi Arabia and the Mirage of Decentralization. In Public Administration and Policy in the Middle East; Dawoody, A., Ed.; Public Administration, Governance and Globalization; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.; Schulz, K.; Vervoort, J.; Van Der Hel, S.; Widerberg, O.; Adler, C.; Hurlbert, M.; Anderton, K.; Sethi, M.; Barau, A. Exploring the governance and politics of transformations towards sustainability. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Laan, L. Changing urban systems: An empirical analysis at two spatial levels. Reg. Stud. 1998, 32, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.H.; Garmestani, A.S.; Karunanithi, A.T. Threshold transitions in a regional urban system. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2011, 78, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J.W. Short-term income growth in the Canadian urban system. Can. Geogr./Géographe Can. 1976, 20, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretagnolle, A.; Daudé, E.; Pumain, D. From Theory to Modelling: Urban Systems as Complex Systems. Cybergeo Eur. J. Geogr. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Pacione, M. Urban environmental quality and human wellbeing—A social geographical perspective. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 65, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, G.; Megaro, A.; Carrubbo, L. Small-Town Citizens’ Technology Acceptance of Smart and Sustainable City Development. Sustainability 2022, 15, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbouKorin, A.A. Spatial analysis of the urban system in the Nile Valley of Egypt. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2018, 9, 1819–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, N. Extended Metropolitan Regions in Asia: A New Spatial Paradigm. In The Extended Metropolis: Settlement Transition in Asia; Ginsburg, N., Koppel, B., McGee, T.G., Eds.; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1991; pp. 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- McGee, T.G. The Emergence of Desakota in Asia: Expanding a Hypothesis. In The Extended Metropolis: Settlement Transition in Asia; Ginsburg, N., Koppel, B., McGee, T.G., Eds.; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Meili, R.; Shearmur, R. Diverse diversities—Open innovation in small towns and rural areas. Growth Chang. 2019, 50, 492–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, L.; Garcilazo, E.; McCann, P. The economic performance of European cities and city regions: Myths and realities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2013, 21, 334–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainet, H. The paradoxical place of small towns in sustainable development policies. What is beyond the images of “places where the living is easy”? Ann. Univ. Paedagog. Crac. Stud. Geogr. 2015, 8, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, D.; Dimitrov, M. As Eastern Europe Shrinks, Rural Bulgaria Is Becoming a Ghost Land. Los Angeles Times, 21 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Waiting for the End in Japan’s Terminal Villages. Forbes, 31 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Petrov, A. Where Did Everyone Go? The Sad, Slow Emptying of Bulgaria’s Vidin. Balkan Insight, 26 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann, K.; Mallach, A. The small city in the urban system: Complex pathways of growth and decline. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2021, 103, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayne, M.; Gibson, C.; Waitt, G.; Bell, D. The cultural economy of small cities. Geogr. Compass 2010, 4, 1408–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, E.J.; Burger, M.J.; Hoogerbrugge, M.M. Borrowing size in networks of cities: City size, network connectivity and metropolitan functions in Europe. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2016, 95, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitt, G.; Gibson, C. Creative small cities: Rethinking the creative economy in place. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 1223–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J. Global and world cities: A view from off the map. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2002, 26, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, D.; Babb, C.; Curtis, C. Doing Research in Urban and Regional Planning: Lessons in Practical Methods; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Quality of Life Program. Implementation Plan. 2020. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/v2030/vrps/qol/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Thrift, N. Not a straight line but a curve, or cities are not mirrors of modernity. In City Visions; Bell, D., Haddour, A., Eds.; Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M. What can cities do to enhance competitiveness? Local policies and actions for innovation. In Urban Competitiveness and Innovation; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2014; pp. 112–136. [Google Scholar]

- Youl, A.H.N. New Horizons in Well-Balanced Development in Korea: Focusing on Innovation Cities and Smart Cities; OECD: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=1113_1113283-nd6fg9yrxr&title=Regional-development (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Mukai, K.; Fujikura, R. One village one product: Evaluations and lessons learnt from OVOP aid projects. Dev. Pract. 2015, 25, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, R. Integrated development of small and medium towns in India. In Regional Science in Developing Countries; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1997; pp. 196–211. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).