The Relationship between Environmental Bullying and Turnover Intention and the Mediating Effects of Secure Workplace Attachment and Environmental Satisfaction: Implications for Organizational Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

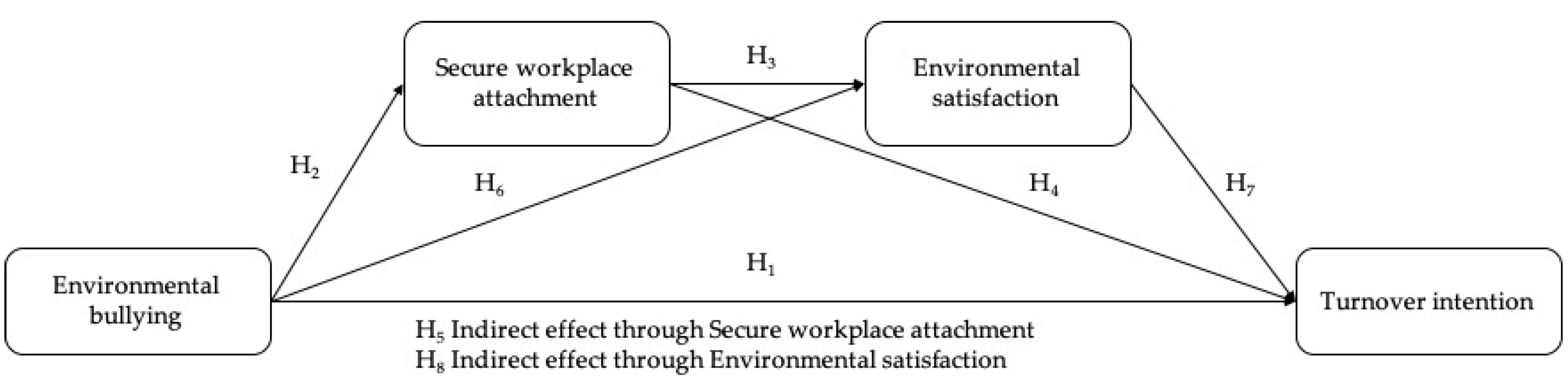

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. The Relationship between Environmental Bullying and Turnover Intention

2.2. The Mediating Role Played by Secure Workplace Attachment

2.3. The Mediating Role Played by Environmental Satisfaction

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Uğural, M.N.; Giritli, H.; Urbański, M. Determinants of the turnover intention of construction professionals: A mediation analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Ha-Brookshire, J. Ethical climate and job attitude in fashion retail employees’ turnover intention, and perceived organizational sustainability performance: A cross-sectional study. Sustainability 2017, 9, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strober, M.H. Human capital theory: Implications for HR managers. Ind. Relat. A J. Econ. Soc. 1990, 29, 214–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leana, C.R.; Van Buren, H.J. Organizational social capital and employment practices. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 538–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salin, D.; Notelaers, G. The effect of exposure to bullying on turnover intentions: The role of perceived psychological contract violation and benevolent behaviour. Work Stress 2017, 31, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Einarsen, S. Outcomes of exposure to workplace bullying: A meta-analytic review. Work Stress 2012, 26, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. How dentists cope with their job demands and stay engaged: The moderating role of job resources. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2005, 113, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, É. Environmental satisfaction at work, satisfaction at work and turnover intention. Study on a sample of French office workers. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Braşov Ser. VII Soc. Sci. Law 2017, 10, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Q.; Wu, S.; McElroy, J.C.; Chen, L. Place attachment, intent to relocate and intent to quit: The moderating role of occupational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 108, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ein-Eli, E.; Rioux, L. Le rôle modérateur du harcèlement environnemental au travail dans la relation entre l’attachement au lieu de travail et le soutien organisationnel perçu. Étude auprès d’un échantillon féminin. Psychol. Trav. Organ. 2022, 28, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D.; Limber, S.; Mihalic, S.F. Blueprints for Violence Prevention, Book Nine: Bullying Prevention Program; Delbert S. Elliott, Ed.; Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; pp. 256–273. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, C.; Hoel, H. A summary review of literature relating to workplace bullying. J. Community Appl. Soc. 1997, 7, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muazzam, A.; Anjum, A.; Visvizi, A. Problem-Focused Coping Strategies, Workplace Bullying, and Sustainability of HEIs. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, T.; Foucher, R.; Gosselin, E. La prévention du harcèlement psychologique au travail: De l’individu à l’organisation. Gestion 2000 2012, 29, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirigoyen, M. Healing the Wounded Soul. In Workplace Bullying: Symptoms and Solutions; Tehrani, N., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 166–178. [Google Scholar]

- Courcy, F.; Morin, A.J.; Madore, I. The effects of exposure to psychological violence in the workplace on commitment and turnover intentions: The moderating role of social support and role stressors. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 34, 4162–4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.; Dejours, C. Le harcèlement au travail et ses conséquences psychopathologiques: Une clinique qui se transforme. Evol. Psychiatr. 2019, 84, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, M.; McCabe, T.J.; Garavan, T.N. Workplace bullying and employee outcomes: A moderated mediated model. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Man. 2020, 31, 1379–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsufyani, A.M.; Almalki, K.E.; Alsufyani, Y.M.; Aljuaid, S.M.; Almutairi, A.M.; Alsufyani, B.O.; Alshahrani, A.S.; Baker, O.G.; Aboshaiqah, A. Impact of work environment perceptions and communication satisfaction on the intention to quit: An empirical analysis of nurses in Saudi Arabia. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, S.L.; Kee, D.M.H.; Tan, C.L. The impact of ethical work climate on the intention to quit of employees in private higher educational institutions. J. South Asian Res. 2016, 2016, 283881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.M.; Altman, I. Place Attachment: A Conceptual Inquiry. In Place Attachment; Altman, I., Low, S.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, B.S.; Stedman, R.C. Sense of place as an attitude: Lakeshore owners’ attitudes toward their properties. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, M.V. Towards an analysis of mental representations of attachment to the home. J. Archit Plan. Res. 1991, 8, 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Comstock, N.; Dickinson, L.M.; Marshall, J.A.; Soobader, M.-J.; Turbin, M.S.; Buchenau, M.; Litt, J.S. Neighborhood attachment and its correlates: Exploring neighborhood conditions, collective efficacy, and gardening. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. What makes neighborhood different from home and city? Effects of place scale on place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrázková, K.; Lisá, E. The Workplace Attachment Styles Questionnaire in Shortened 9-Item Version. In Psychology Applications & Developments; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2021; pp. 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss. In Attachment; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Comparing the Theories of Interpersonal and Place Attachment. In Place Attachment: Advances in Theory Methods, and Applications; Manzo, L.C., Devine-Wright, P., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Scrima, F. The psychometric properties of the workplace attachment style questionnaire. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 2285–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, K.; Horowitz, L.M. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 226–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, J.-F.; Iodice, P.; Radic, K.; Scrima, F. The reverse buffering effect of workplace attachment style on the relationship between workplace bullying and work engagement. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1112864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, L.G.; Legault, L.R.; Tuson, K.M. The environmental satisfaction scale. Environ. Behav. 1996, 28, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlopio, J.R. Construct validity of a physical work environment satisfaction questionnaire. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. The experienced psychological benefits of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Hall, C.M.; Yu, K.; Qian, C. Environmental satisfaction, residential satisfaction, and place attachment: The cases of long-term residents in rural and urban areas in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Shen, C.; Wang, E.; Hou, Y.; Yang, J. Impact of the perceived authenticity of heritage sites on subjective well-being: A study of the mediating role of place attachment and satisfaction. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, A.; Yuksel, F.; Billim, Y. Destination attachment: Effects on customer satisfaction and cognitive, affective and conative loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.C.; Dwyer, L. Residents’ place satisfaction and place attachment on destination brand-building behaviors: Conceptual and empirical differentiation. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 1026–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.T. The satisfaction-place attachment relationship: Potential mediators and moderators. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2593–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrima, F.; Rioux, L.; Guarnaccia, C. The relationship between workplace attachment and satisfaction. TPM 2019, 26, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajdukovic, I.; Gilibert, D.; Labbouz, D. Confort au travail: Le rôle de l’attachement et de la personnalisation dans la perception de la qualité de l’espace de travail. Psychol. Trav. Organ. 2014, 20, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrima, F.; Mura, A.L.; Nonnis, M.; Fornara, F. The relation between workplace attachment style, design satisfaction, privacy and exhaustion in office employees: A moderated mediation model. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 78, 101693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.M.; Ogilvie, M. Examining the effects of environmental interchangeability with overseas students: A cross cultural comparison. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Log. 2001, 13, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G.; Hosking, K. Nonpermanent residents, place attachment, and “sea change” communities. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, K.; Suryanto, A.; Utami, P. Mapping cultural vulnerability in volcanic regions: The practical application of social volcanology at Mt Merapi, Indonesia. Environ. Hazards 2012, 11, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, M. Continuities and discontinuities of place. J. Environ. Psychol. 2000, 20, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Li, X.; Dong, S.; Fu, J. Work stress and turnover intention among Chinese rural school principals: A mediated moderation study. PsyCh J. 2021, 10, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehr, R.; Yam, K.C.; He, W.; Chiang, J.T.J.; Wei, W. Polluted Work: A Self-Control Perspective on Air Pollution Appraisals, Organizational Citizenship, and Counterproductive Work Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2017, 143, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Ouyang, Q.; Cao, B. A study on the effects of thermal, luminous, and acoustic environments on indoor environmental comfort in offices. Build. Environ. 2012, 49, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin Danielsson, C.; Theorell, T. Office Employees’ Perception of Workspace Contribution: A Gender and Office Design Perspective. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 995–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chungkham, H.S.; Wulff, C.; Westerlund, H. Office design’s impact on sick leave rates. Ergonomics 2014, 57, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zientara, P.; Adamska-Mieruszewska, J.; Bąk, M. Unpicking the mechanism underlying hospitality workers’ intention to join a union and intention to quit a job. Evidence from the UK. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 108, 103355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poilpot-Rocaboy, G.; Notelaers, G.; Hauge, L.J. Exposition au harcèlement psychologique au travail: Impact sur la satisfaction au travail, l’implication organisationnelle et l’intention de départ. Psychol. Trav. Organ. 2015, 21, 358–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Muñoz, A.; Baillien, E.; De Witte, H.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Pastor, J.C. Cross-lagged relationships between workplace bullying, job satisfaction and engagement: Two longitudinal studies. Work Stress 2009, 23, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, A.L.; Eberly, M.B.; Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R. Surveying the forest: A meta-analysis, moderator investigation, and future-oriented discussion of the antecedents of voluntary employee turnover. Pers. Psychol. 2017, 71, 23–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, É. La Satisfaction Environnementale au Travail des Employés de Bureaux. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Paris Nanterre, Nanterre, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ein-Eli, E.; Scrima, F.; Rioux, L. Construction and first validation of a French scale of environmental harassment at work (EHWS). Bull. Transilv. Univ. Brasov. Ser. VII Soc. Sci. Law 2022, 15, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, E.; Mogenet, J.-L.; Rioux, L. Développement et première validation d’une Échelle de Satisfaction Environnementale au Travail (ESET). Psychol. Française 2016, 61, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabli-Bouzid, D.; Moffat, E.; Rioux, L. Âge Subjectif, Âge Subjectif au Travail et Satisfaction Environnementale au Travail. Etude sur un échantillon d’employés tunisiens. In Les Pays du Sud Face Aux Défis du Travail; René Mokounkolo, R.N., Courcy, F., Sima, M.N., Achi, N., Eds.; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2019; pp. 247–258. [Google Scholar]

- Mobley, W.H.; Griffeth, R.W.; Hand, H.H.; Meglino, B.M. Review and conceptual analysis of the employee turnover process. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 493–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P. Les relations entre l’implication au travail, les comportements de citoyenneté organisationnelle et l’intention de retrait. Eur. Rev. App. Psychol. 2006, 56, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regession Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alola, U.V.; Avci, T.; Ozturen, A. Organization Sustainability through Human Resource Capital: The Impacts of Supervisor Incivility and Self-Efficacy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, M.; Van Dyk, J. Workplace bullying and turnover intention: Exploring work engagement as a potential mediator. Psychol. Rep. 2017, 121, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoel, H.; Sheehan, M.J.; Cooper, C.L.; Einarsen, S. Organisational Effects of Workplace Bullying. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: Developments in Theory, Research, and Practice; Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 129–149. [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Fida, R. A time-lagged analysis of the e ect of authentic leadership on workplace bullying, burnout, and occupational turnover intentions. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2014, 23, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; De Boer, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Job demands and job resources as predictors of absence duration and frequency. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 62, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, L.C. For better or worse: Exploring multiple dimensions of place meaning. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskams, M.; Haynes, B. Environmental demands and resources: A framework for understanding the physical environment for work. Facilities 2021, 39, 652–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djurkovic, N.; McCormack, D.; Casimir, G. Workplace bullying and intention to leave: The moderating effect of perceived organisational support. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2008, 18, 405–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glambek, M.; Matthiesen, S.B.; Hetland, J.; Einarsen, S. Workplace bullying as an antecedent to job insecurity and intention to leave: A 6-month prospective study. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2014, 24, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendron, B.P.; Williams, K.R.; Guerra, N.G. An analysis of bullying among students within schools: Estimating the effects of individual normative beliefs, self-esteem, and school climate. J. Sch. Violence 2011, 10, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawker, D.S.J.; Boulton, M.J. Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. J. Child Psychol. Psych. 2000, 41, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Moore, M.; Kirkham, C. Self-esteem and its relationship to bullying behaviour. Aggress. Behav. 2001, 27, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemesh, D.O.; Heiman, T. Resilience and Self-Concept as Mediating Factors in the Relationship between Bullying Victimization and Sense of Well-Being among Adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2021, 26, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D.A.; Maxwell, M.A.; Dukewich, T.L. Targeted peer victimization and the construction of positive and negative self-cognitions: Connections to depressive symptoms in children. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2010, 39, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahnow, R.; Tsai, A. Crime Victimization, Place Attachment, and the Moderating Role of Neighborhood Social Ties and Neighboring Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaiuto, M.; Breakwell, G.M.; Cano, I. Identity processes and environmental threat: The effects of nationalism and local identity upon perception of beach pollution. J. Commun. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 6, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, F. Impact of place attachment on risk perception: Exploring the multidimensionality of risk and its magnitude. Stud. Psychol. 2013, 34, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury-Bahi, G.; Félonneau, M.L.; Marchand, D. Processes of place identification and residential satisfaction. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Perkins, D.D.; Brown, G. Place attachment in a revitalizing neighborhood: Individual and block levels of analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.D. Patterns of infant-mother attachments: Antecedents and effects on development. Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 1985, 61, 771–791. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ainsworth, M.S. Attachments beyond infancy. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaiuto, M.; Alves, S.; De Dominicis, S.; Petruccelli, I. Place attachment and natural hazard risk: Research review and agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 48, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, P.; Erdlenbruch, K.; Gramaglia, C. Why do people continue to live near polluted sites? Empirical evidence from Southwestern Europe. Environ. Mod. Assess. 2021, 26, 631–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, G.; Leon-Perez, J.M.; Arenas, A. Are Bullying Behaviors Tolerated in Some Cultures? Evidence for a Curvilinear Relationship Between Workplace Bullying and Job Satisfaction Among Italian Workers. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flouri, E.; Buchanan, A. Life satisfaction in teenage boys: The moderating role of father involvement and bullying. Aggress. Behav. 2002, 28, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Assche, J.; Haesevoets, T.; Roets, A. Local norms and moving intentions: The mediating role of neighborhood satisfaction. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 63, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Rutter, N. Is satisfaction the key? The role of citizen satisfaction, place attachment and place brand attitude on positive citizenship behavior. Cities 2014, 38, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.E.; Cole, D.A. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tambur, M.; Vadi, M. Workplace bullying and organizational culture in a post-transitional country. Int. J. Manpow. 2012, 33, 754–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pheko, M.M.; Monteiro, N.M.; Segopolo, M.T. When work hurts: A conceptual framework explaining how organizational culture may perpetuate workplace bullying. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2017, 27, 571–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonnis, M.; Mura, A.L.; Scrima, F.; Cuccu, S.; Fornara, F. The Moderation of Perceived Comfort and Relations with Patients in the Relationship between Secure Workplace Attachment and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors in Elderly Facilities Staff. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | 39.80 | 10.17 | 1 | |||||

| 2 | Sex (1 = M, 2 = F) | - | - | 0.21 ** | 1 | ||||

| 3 | Environmental bullying | 2.16 | 0.71 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 1 | |||

| 4 | Environmental satisfaction | 3.39 | 0.66 | 0.00 | 0.16 * | −0.52 ** | 1 | ||

| 5 | Secure workplace attachment | 3.86 | 1.51 | 0.08 | 0.41 ** | −0.42 ** | 0.55 ** | 1 | |

| 6 | Turnover intention | 2.21 | 1.26 | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.45 ** | −0.45 ** | −0.47 ** | 1 |

| Secure Workplace Attachment (R2 = 0.35) | Environmental Satisfaction (R2 = 0.41) | Turnover Intention (R2 = 0.27) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | LLCI | ULCI | B | SE | LLCI | ULCI | B | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Environmental bullying | −0.42 | 0.06 | −0.55 | −0.30 | −0.35 | 0.06 | −0.48 | −0.22 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.39 |

| Secure workplace attachment | 0.41 | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.55 | −0.32 | 0.08 | −0.48 | −0.16 | ||||

| Environmental satisfaction | −0.17 | 0.08 | −0.33 | −0.02 | ||||||||

| Covariates | ||||||||||||

| Sex | 0.40 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.52 | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.14 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.07 | −0.00 | 0.27 |

| Age | 0.05 | 0.06 | −0.07 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.10 | 0.13 | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.20 | 0.05 |

| Effect | SE | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect (BUL→TUR) | 0.47 | 0.07 | <0.001 | 0.33 | 0.60 |

| Direct effect (BUL→TUR) | 0.23 | 0.07 | =0.002 | 0.09 | 0.39 |

| Indirect effect | Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | |

| BUL→ATT→TUR | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.21 | |

| BUL→SAT→TUR | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.15 | |

| BUL→ATT→SAT→TUR | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moffat, É.; Rioux, L.; Scrima, F. The Relationship between Environmental Bullying and Turnover Intention and the Mediating Effects of Secure Workplace Attachment and Environmental Satisfaction: Implications for Organizational Sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11905. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511905

Moffat É, Rioux L, Scrima F. The Relationship between Environmental Bullying and Turnover Intention and the Mediating Effects of Secure Workplace Attachment and Environmental Satisfaction: Implications for Organizational Sustainability. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11905. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511905

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoffat, Éva, Liliane Rioux, and Fabrizio Scrima. 2023. "The Relationship between Environmental Bullying and Turnover Intention and the Mediating Effects of Secure Workplace Attachment and Environmental Satisfaction: Implications for Organizational Sustainability" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11905. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511905

APA StyleMoffat, É., Rioux, L., & Scrima, F. (2023). The Relationship between Environmental Bullying and Turnover Intention and the Mediating Effects of Secure Workplace Attachment and Environmental Satisfaction: Implications for Organizational Sustainability. Sustainability, 15(15), 11905. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511905