A Systematic Review of the Bioactivity of Jatropha curcas L. (Euphorbiaceae) Extracts in the Control of Insect Pests

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

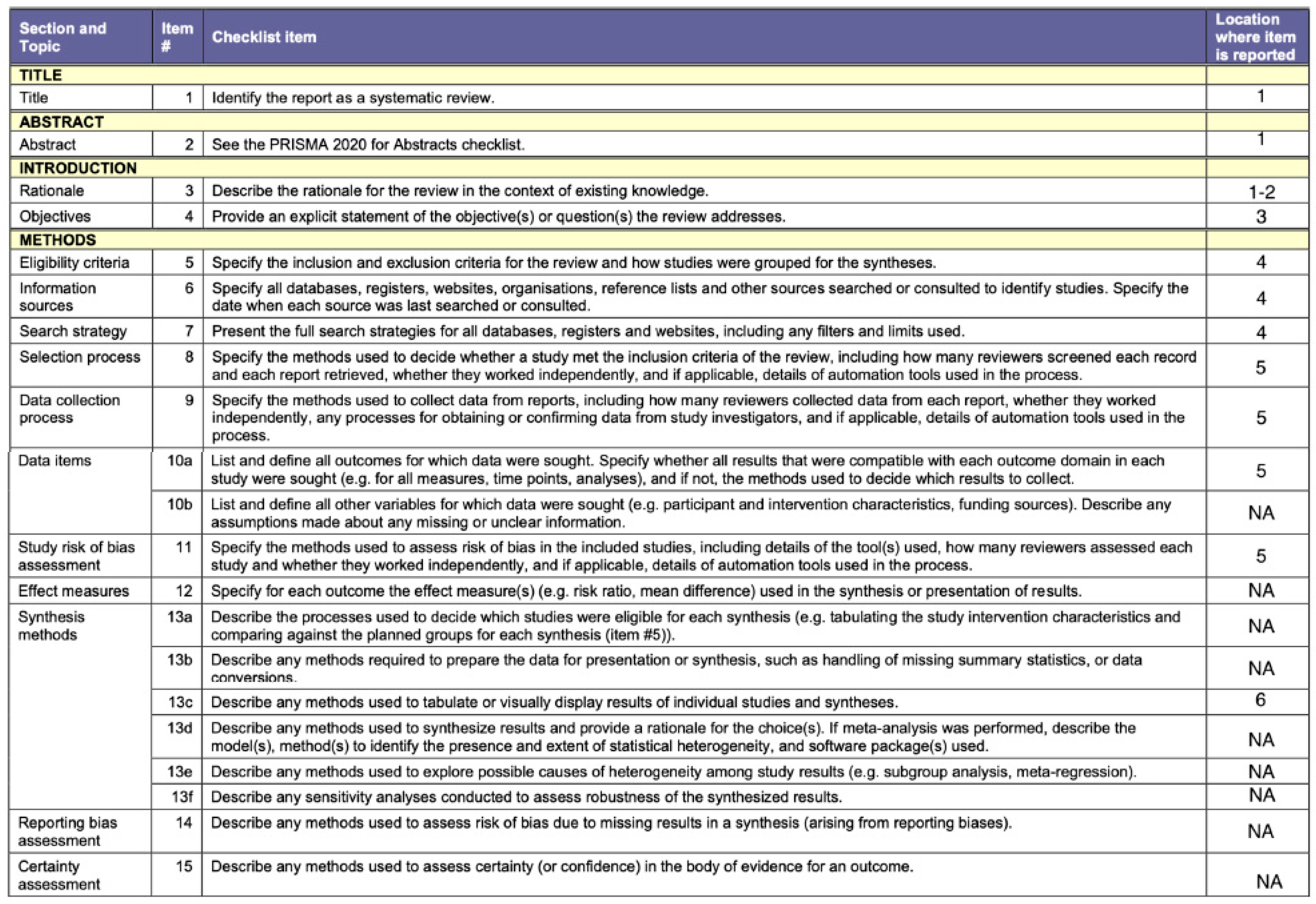

2.1. Protocol and Guidelines Followed

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection Process

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.7. Summary of Evidence

3. Results

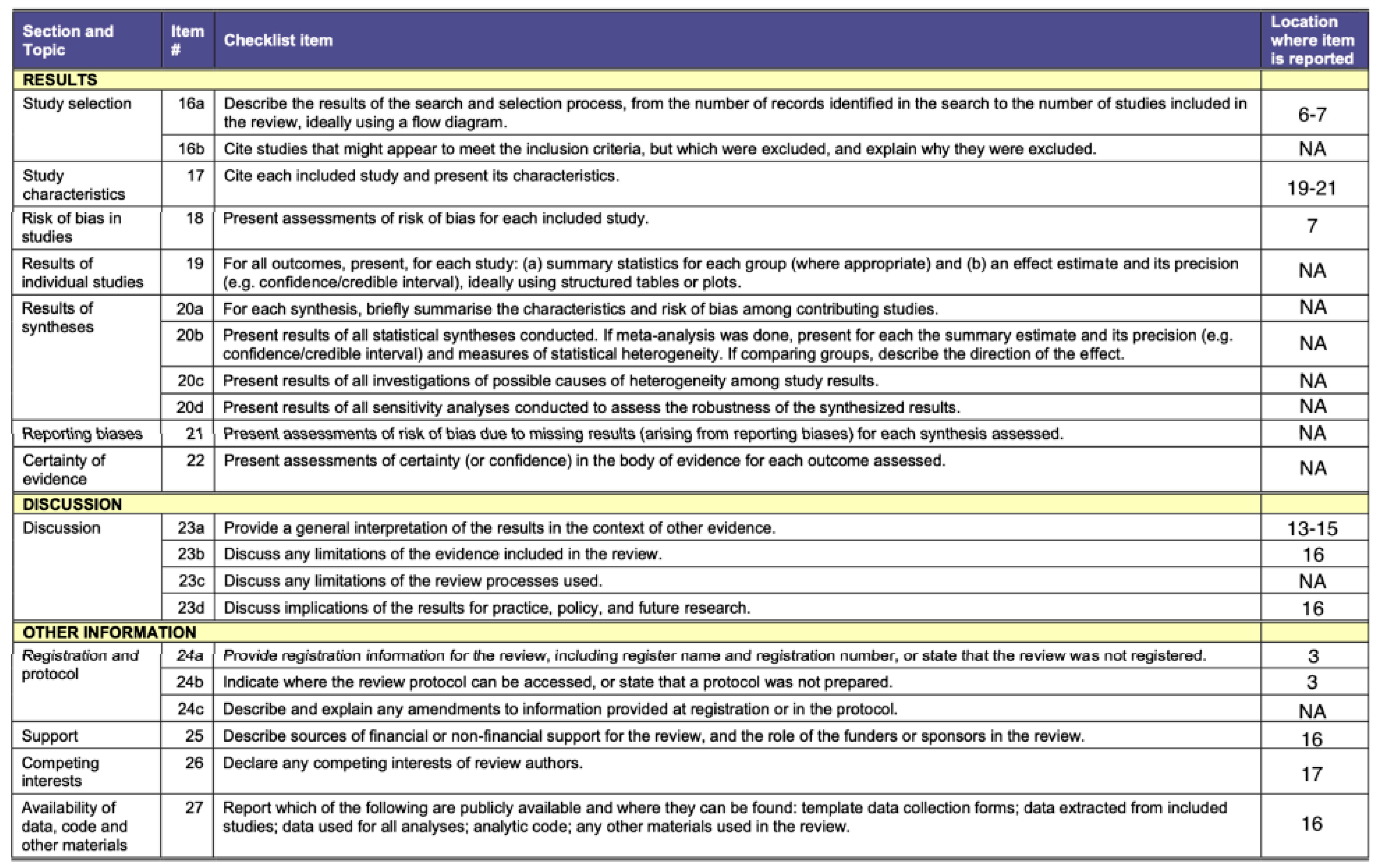

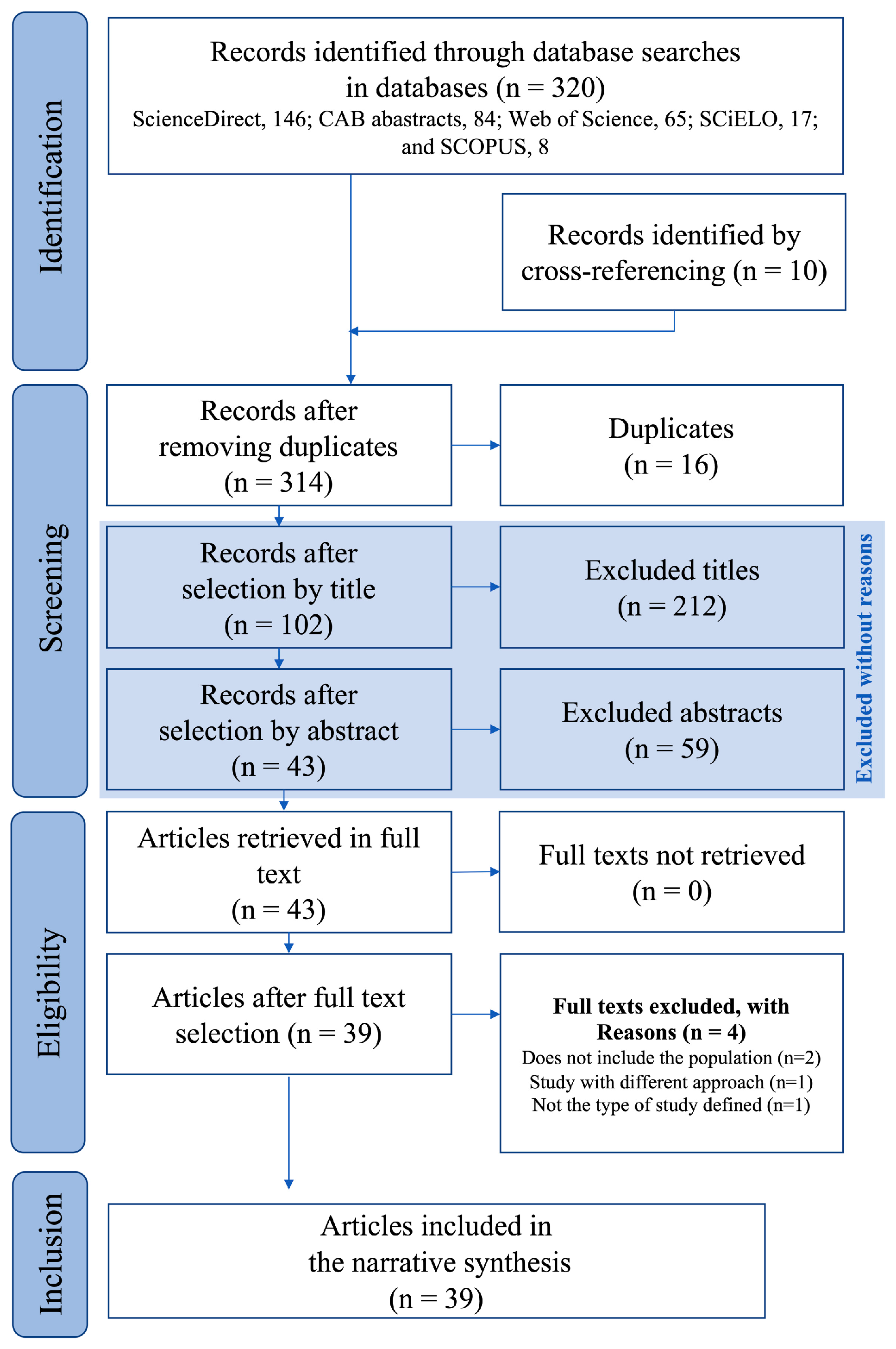

3.1. Studies included in the Evidence Synthesis

3.2. Main Characteristics of the Studies included in the Systematic Review

3.3. Risk of Bias within the Studies

3.4. Summary of Evidence by Order of Plague Insects

3.4.1. Lepidoptera

- Plutella xylostella

- 2.

- Spodoptera frugiperda

- 3.

- Helicoverpa armigera

- 4.

- Copitarsia decolora

- 5.

- Other species

3.4.2. Coleoptera

- Sitophilus zeamais

- 2.

- Callosobruchus maculatus

- 3.

- Triboleum castaneum

- 4.

- Podagrica uniforma

3.4.3. Hemiptera

- Brevicoryne brassicae

- 2.

- Other species

3.4.4. Diptera

3.4.5. Homoptera

3.4.6. Isoptera

3.4.7. Othoptera

3.4.8. Thysanoptera

3.5. Chemical Compounds Identified in the Botanical Parts of Jatropha curcas

4. Discussion

4.1. Objective 1—Identify and Map the Body of Evidence Published on the Use of J. curcas against Insect Pests

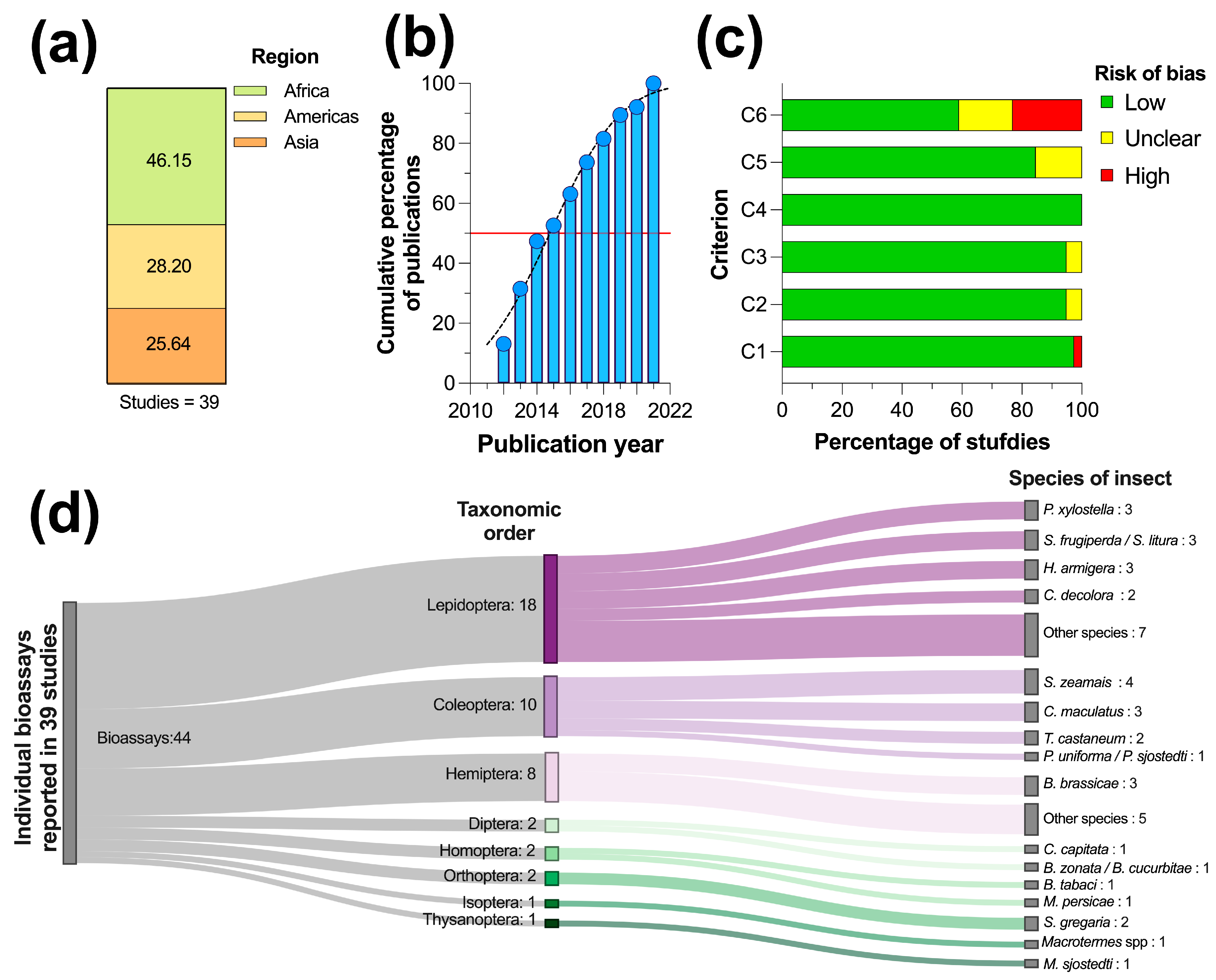

4.2. Objective 2—Summarize the Body of Evidence

4.3. Objective 3—Identify the Main Chemical Compounds with Insecticidal and Insectistatic Bioactivity

4.4. Perspectives and Future Research on the Botanical Extracts of J. curcas

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study/Country | Botanical Extract | Methods | Bioactivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Addisu et al. [68]/ Ethiopia | Aqueous extract of J. curcas seeds | The extract was evaluated at four concentrations (10, 20, 30, and 35% (w/v)) on Macrotermes ssp. worker termites by topical application. The percentage of mortality and repellency was evaluated | The aqueous extract caused 100% mortality on worker termites at a concentration of 20 to 35% 72 h after application |

| Amoabeng et al. [32]/ Ghana | Aqueous extract of J. curcas leaves | The extract was sprayed (3% (w/v)) on cabbage plants containing P. xylostella larvae in open field. In a mesh cage experiment, adult aphids of B. brassicae were transferred. The percentage mortality rate was calculated | The 3% aqueous extract showed a 66% larval mortality of P. xylostella, while the infestation reduction score of B. brassicae was 0 (colonies absent) |

| Babarinde et al. [50]/ Nigeria | Seed oil from toxic varieties of J. curcas | The seed oil was obtained by roasting one portion, cooking in distilled water, and the last was used raw. Two bioassays of fumigation (50, 100, 150, and 200 µL/L) and contact toxicity (0.30, 0.60, 0.90, 1.20, and 1.50 µL/cm2) evaluated the percentage of mortality on adult insects of S. zeamais | Exposure of S. zeamais to 200 μL/L of roasted seed oil showed a mortality of 84.68% at 24 h, compared to 40.28 and 47.80% observed in cooked and raw seed oil |

| Bashir et al. [69]/ Sudan | Hexanic extract of J. curcas seed oil | Concentrations of J. curcas seed oil (5, 10, 15, and 20% (v/v)) were tested through a contact and ingestion toxicity bioassay on S. gregaria nymphs. Effects on development, mortality, antifeedant activity and hatchability of eggs were evaluated | All concentrations caused nymph mortality (range 22.4 to 59.2%). The 10% concentration delayed development time and reduced the percentage of egg hatching. The 5% concentration caused an anti-feeding effect of 50% |

| Bashir et al. [70]/ Sudan | Hexanic extract of J. curcas seed oil | The extract was evaluated in a contact bioassay, sprayed at 10% (v/v) on S. gregaria nymphs. The outcomes included mortality, percentage of deformed adults, affectations in development, effect on fecundity, and hatchability of eggs. The phagodisuasive effect was recorded at a concentration of 5% (v/v) | The 5% extract produced an anti-feeding effect of 78.92%, a nymphal mortality of 43.39% at the 10% concentration and significantly reduced female fecundity by 42.2% |

| Botti et al. [59]/ Brazil | J. curcas seed oil | 0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, and 3.0% (v/v) of J. curcas seed oil were sprayed on cabbage leaf discs containing green aphids B. brassicae and mortality was evaluated at 24, 48, and 72 h | The oil caused a mortality of between 40 and 60% of the aphids in the first 24 and 48 h after application at 3.0% |

| de Oliveira et al. [47]/ Brazil | Aqueous extract of J. curcas seed oil | A 3% aqueous seed oil extract was applied in a contact toxicity bioassay on D. saccharalis eggs. Its effect on egg hatching was evaluated | With the treatment, only 60% hatched and an increase in the embryonic period of 7 days was observed |

| Diabaté et al. [38]/ Ivory Coast | Aqueous extract of J. curcas seed | The extract was sprayed at different concentrations (50 and 80 g/L) on rural, randomized and experimental plots of tomato for the control of adult insects of B. tabaci and larvae of H. armiguera in field efficiency trials evaluating their presence or absence | The extract at 80 g/L reduced the number of B. tabaci insects between 0.13 and 2.26 among the plots. A moderate reduction in the number of H. armiguera larvae was observed (range 0.0 to 0.03) |

| Devappa et al. [35]/ India | Phorbol ester fractions of J. curcas seed oil | The phorbol ester fractions and the phorbol ester-rich extract were applied topically (0.0313, 0.0625, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 20 mg/mL−1) and by ingestion (0.0625, 0.125 and 0.25 mg/mL−1) on third instar larvae of S. frugiperda per treatment, calculating the percentage of mortality, consumption, and weight | The enriched fraction showed contact toxicity with a LC50 of 0.83 mg mL−1. The extract decreased feed consumption by 33%, relative growth by 42%, and feed conversion efficiency by 38% at 0.25 mg mL−1. Feed intake reduction was the highest (39 and 45%) with 0.0625 and 0.125 mg |

| Figueroa-Brito et al. [40]/ Mexico | Aqueous extract of J. curcas seed powder | The aqueous extract of seed powder was tested at 1 and 5% (v/v) in artificial diet on C. decolora larvae through an ingestion bioassay in a completely randomized design, evaluating the percentage of mortality and insectatic activity | Aqueous seed extract at 5% ppm reduced larval viability of C. decolora by 46% |

| Figueroa-Brito et al. [41]/ Mexico | Acetone extract of shell, kernel, and almond nut from J. curcas seeds | Acetone extracts of shell, kernell, and almond nut were obtained from the seeds. Ingestion bioassays were performed under laboratory (250, 500, 1000, 1500, and 2000 ppm) and greenhouse (250, 500 and 1000 ppm) conditions against C. decolora in cabbage plants. Insecticidal and insecticidal activity was evaluated | The extracts of almond nut and shell plus kernell at 500 and 1500 ppm caused the highest percentage of deformations in pupae and adults, causing a mortality of 50% in larvae. Almond nut was active in greenhouse test (250–1000 ppm) |

| Guerra-Arevalo et al. [42]/ Peru | Resin of J. curcas | Five resin treatments (10, 20, 30, and 40% (v/v)) were evaluated in H. grandella larvae on S. macrophylla leaf discs. Disc consumption, survival, mortality and larval activity were measured. | The resin at a concentration of 40% caused a mortality of 67% and a larval activity < 30% in H. grandella larvae |

| Habib-ur-Rehman et al. [57]/ Pakistan | Methanolic, chloroformic, petroleum ether, and n-hexane of J. curcas leaves | The extracts were evaluated at different concentrations (5, 10, and 15% (v/v)) through a toxicity bioassay on adult insects of T. castaneum and R. dominica. The percentage of mortality was evaluated 24, 48 and 72 h after application of the treatments | Methanolic extract at a concentration of 15% caused 37.32% mortality on T. castaneum after 72 h of application, as well as 49.17% mortality on R. dominica |

| Holtz et al. [62]/ Brazil | Green fruit seed and green and dried fruit seed oil of J. curcas | The extracts were applied in ingestion bioassays (0.0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5 and 3.0% (w/v)) on cabbage leaves with green aphids M. persicae, evaluating mortality over time periods of 24, 48 and 72 h | The best results were obtained 48 h after the application of nut oil at 2.5% and 72 h with a mortality between 61 and 71% on M. persicae |

| Holtz et al. [67]/ Brazil | Leaves, stem with or without bark, fruit and seeds of J. curcas | Aqueous extract and seed oil were evaluated on nymphs and adult insects of P. citri through contact and ingestion bioassays on coffee leaf discs at different concentrations (0.0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5 and 3.0% (w/v)) | All aqueous extracts in contact application showed satisfactory insecticidal activity, reaching 91.6% mortality at three concentrations (1.5, 2.0 and 3.0% (w/v)) |

| Ingle et al. [37]/ India | Leaves, bark, seeds, and seed hulls of J. curcas | The crude methanolic extracts were evaluated through an ingestion bioassay on S. litura larvae at a concentration of 5% (w/v), evaluating the insecticidal activity by counting dead insects in a period of 72 h after application | The leaf extract showed a 60% mortality compared to the other parts of the plant 72 h after application |

| Ingle et al. [33]/ India | Leaves, bark, seeds, seed hulls, and root of J. curcas | Methanolic extracts were evaluated at 5% (w/v) on P. xylostella larvae and 5, 10 and 15% (w/v) was used on H. armigera larvae by means of bioassays of ingestion by immersion of cabbage leaf discs. Larval mortality at 72 h and antifeedant activity were determined on treated cotton leaves | The 15% leaf extract showed antifeedant activity against H. armigera by reducing larval weight by 42% and causing 60% mortality. Seed husk extract caused 100% mortality at 5% against P. xylostella |

| Ishag et al. [43]/ Sudan | Aqueous extract and oil of J. curcas seeds | The extract was evaluated at 5, 10, 15 and 20% (v/v) through a contact toxicity bioassay on E. insulana eggs | The aqueous extract reduced the percentage of egg hatching, with the 10% concentration being the most effective |

| Jagdish et al. [39]/ India | J. curcas seed oil | Different combinations of biopesticide and J. curcas seed oil treatments were applied in experimental plots over a period of three years for the control of H. armiguera and T. orichalcea, evaluating the percentage of damage to the ear | Treatments that included J. curcas seed oil were the most effective in reducing the number of larval populations of both pest insects |

| Jide-Ojo et al. [51]/ Nigeria | Aqueous extract of leaves, oil and juice of J. curcas seeds | The oviposition-deterrent activity and corn grain-protective activity of the different treatments (0, 5, 10, 50, and 100 ppm) of the extracts against S. zeamais were evaluated | Seed oil at 100 ppm produced 93% protection against grain damage, inhibited oviposition by 90%, decreased adult hatching by 92.3% and caused 90% mortality |

| Khani et al. [48]/ Malasya | Pretoleum ether extract of J. curcas seeds | The extract was tested at different concentrations (2, 4, 6, 8, and 10% (w/v)) through food and contact bioassays on third instar larvae and eggs of C. cephalonica. The percentage of mortality, the anti-feeding activity and its effect on egg hatchability were evaluated | The extract produced larval susceptibility, with a LC50 of 13.22 µL/mL. While at 12 and 20 µL/mL it caused a mortality of 66.5 and 98%, respectively, with an anti-feeding action of 48.08% at 6 µL/g and hatchability of 58% at 2 µL/mL |

| Kolawole et al. [55]/ Nigeria | Ethanolic extract of J. curcas seeds | The extract was used at 0, 5000, 10,000, 15,000, and 20,000 ppm in an ingestion bioassay with cowpea seeds infested with adult C. maculatus insects. Oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant glutathione enzymes were evaluated | The extract at 20,000 ppm increased oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation. While at 5000 ppm it increased glutathione reductase, indicating the extent of damage to vital organs |

| Kona et al. [45]/ Sudan | Petroleum ether extract from J. curcas seeds | The extract was applied in contact bioassay on tomato leafminer T. absoluta eggs at 62.5, 125, 250, 250, 500, and 1000 mg/L. The larvae were exposed to 2000, 4000, 6000, and 8000 mg/L. Mortality of eggs and larvae was recorded | The concentration of 125 mg/L showed the highest mortality (25%) in eggs and a higher larval mortality of 85 to 100% was observed at 4000 and 8000 mg/L, respectively |

| Mwine et al. [34]/ Uganda | Latex from J. curcas stems | Aqueous latex extract obtained from stems was evaluated at 50 and 25% (v/v) and sprayed on experimental plots of cabbage crops, evaluating the efficiency in controlling infestation numbers of P. xylostella larvae and colonies of B. brassicae aphids | The 50% extract showed a moderate reduction in B. brassicae infestation, while the same concentration produced a slight 11% reduction in the number of P. xylostella larvae |

| Onunkun et al. [58]/ Nigeria | Aqueous extract of J. curcas seeds | The extract was tested in a 10% (w/v) ingestion bioassay on okra plants infested with adult insects of P. uniforma and P. sjostedti. The reduction in the number of insects was determined | The extract at 10% concentration reduced flea beetle populations of P. uniforma and P. sjostedti by 64% |

| Opuba et al. [53]/ Nigeria | Aqueous extract of J. curcas leavess | The aqueous extract was evaluated through an ingestion bioassay by spraying 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0% (w/v) on cowpea seeds containing adult C. maculatus insects | All concentrations showed insecticidal activity. The lowest concentration produced 94–98% mortality and reduced the oviposition by 81.04% |

| Orozco-Santos et al. [60]/ Mexico | J. curcas seed oil | The extract was evaluated in a 1 and 4% (v/v) ingestion bioassay on the Asian citrus psyllid D. citri. The population of live immatures before and after treatment was quantified. | The treatment was effective in reducing the number of nymphs between 76.3 and 92.5% in relation to the initial population |

| Pant et al. [56]/ India | J. curcas seed oil with or without eucalyptus and P. glabra | The evaluation of the insecticidal activity was carried out in direct contact bioassays (300, 600, 900, 1200, and 1500 ppm) of the nanoemulsion of eucalyptus alone and with aqueous filtrate of P. glabra and J. curcas on Tribolium spp. | The 300 and 1500 ppm nanoemulsion produced 88–100% mortality against insects with LC50 for the nanoemulsions with and without the aqueous filtrate were 0.1646 and 5.4872 mg L−1 |

| Rampadarath et al. [66]/ Mauritius | Bark, leaves, roots, and seeds J. curcas seeds | Crude ethyl acetate extracts were tested by ingestion bioassays (200, 400, and 800 mg/L (w/v)) on larvae of two insects, B. zonata and B. cucurbitae. Larval mortality was determined | The bark extract after 24 h produced a mortality ranging between 66.67 and 70% for both larvae of B. cucurbitae and B. zonata, respectively |

| Ribeiro et al. [36]/ Brazil | Methanolic extract of J. curcas fresh and dry leaves | Fractions of methanolic extracts of seven accessions were evaluated. The extracts were evaluated through a bioassay of ingestion of fresh and dried leaves (1000 mg/kg−1) on S. frugiperda larvae. Insecticidal and insecticidal activity was evaluated | Extracts of EMB accessions of fresh and dried leaves showed the best result for larval mortality of S. frugiperda with (range 60 and 56.67%). |

| Sharma et al. [44]/ India | Acetonic extract of J. curcas seeds | Dilutions were made with water of the extract at 0.00, 0.625, 1.25, 2.50, 5.00 and 10.00% (v/v). Treatments were tested in an ingestion bioassay against S. oblicua larvae fed on treated resin leaves. Larval and pupal weight, percentage mortality, pupation and adult emergence were evaluated | The 5.0% concentration increased the percentage of larval mortality by 33.3%, as well as a decrease in pupation from 26.66% to 1.25%. |

| Silva et al. [49]/ Brazil | Aqueous extract and powder of J. curcas seeds | Two bioassays were used, the first with plant seeds and the second with aqueous extracts and seed and pericarp powder at 5 and 10% (w/v) on adults of S. zeamais, R. dominica, T. castaneum, and O. surinamensis | The aqueous extracts were active at 10%, causing 75, 100, 60, and 90% mortality on S. zeamais, R. dominica, T. castaneum, and O. surimanensis, respectively |

| Silva et al. [65]/ Brazil | Aqueous extract of J. curcas leaves | The aqueous extract was evaluated through an ingestion bioassay (10% (w/v)) on neonate larvae of C. capitata. Larval mortality and control efficiency were evaluated | The aqueous extract was toxic and effective in the control of C. capitata larvae causing 95.6% mortality at 10% |

| Sumantri et al. [61]/ Indonesia | Aqueous extract of J. curcas seeds | The experiment was conducted using residual toxicity, by applying 0.5 and 0.25% (v/v) aqueous extract solution on adults of N. viridula per treatment. The mortality rate was recorded daily | The extracts showed 80 to 100% mortality on N. viridula, and were highly toxic with an LC50 of 0.026% |

| Uddin li et al. [54]/ Nigeria | Aqueous extract of J. curcas seeds | The extract was applied by contact at 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5% (w/v) on cowpea seeds infested with newly adult insects of C. maculatus, evaluating mortality, oviposition and emergence of the progeny | The 2.5% treatment increased mortality by 2.25 times, decreased oviposition and decreased adult emergence by 0.75 times |

| Ugwu et al. [46]/ Nigeria | J. curcas seed oil | Petroleum ether extract of seeds was sprayed at 10 mL/L on cowpea seedlings. The number of M. sjostedti thrips and M. vitrata larvae, as well as damage to cowpea pods, was evaluated | The treatment reduced the population of thrips of M. sjostedti by 52.07% and 59.12% for the pod borer M. vitrata |

| Ugwu et al. [64] /Nigeria | Aqueous and ethanolic extract of J. curcas seeds | The aqueous and ethanolic seed extract were evaluated at concentrations of 75 and 100% (w/v) through a bioassay of residual action and contact toxicity on adult insects of P. fusca. Mortality was evaluated for 24 h | Aqueous and ethanolic extracts of seeds at 75% and 100% concentrations had a residual effect of 3.33 and 4.33 at 40 min and 1.67 contact effect on P. fusca |

| Ukpai et al. [52] /Nigeria | Seed powder of J. curcas | Seed powders were evaluated at different doses (2.5, 5.0, 7.5 and 10.0 g) through an ingestion bioassay on adult S. zeamais insects. The number of insects killed per treatment was evaluated | Treatment with 10 g of seed powder caused significant mortality of adult S. zeamais insects. |

| Yadav et al. [63]/ India | Methanolic extract of J. curcas leaves | The extract was tested in nine concentrations in combination with different plants through an ingestion bioassay, using sorghum leaves with M. sacchari aphids. Mortality and reproductive rates were measured | The methanolic extract formulation that included J. curcas showed a mortality rate of 68.35% and 56.57% efficiency in controlling aphids of M. sacchari |

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization. More People, More Food… Worse Water?—Water Pollution from Agriculture: A Global Review; United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2018; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Pollutants from Agriculture a Serious Threat to World’s Water; United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schreinemachers, P.; Tipraqsa, P. Agricultural pesticides and land use intensification in high, middle and low income countries. Food Policy 2012, 37, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Preventing Disease through Healthy Environments: Exposure to Highly Hazardous Pesticides: A Major Public Health Concern; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization. The International Code of Conduct on Pesticide Management—Guidelines on Highly Hazardous Pesticides; United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2016; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous, Z.; Datta, A.; Anwar, M. Synthetic pheromone lure and apical clipping affects productivity and profitability of eggplant and cucumber. Int. J. Veg. Sci. 2018, 24, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timprasert, S.; Datta, A.; Ranamukhaarachchi, S. Factors determining adoption of integrated pest management by vegetable growers in Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Thailand. Crop Prot. 2014, 62, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A. Pesticide residue in food commodities: Advances in Analysis. In Evaluation, and Management, with Particular Reference to India; Agrobios: Jodhpur, India, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- International Programme on Chemical Safet. INCHEM: Internationally Peer Reviewed Chemical Safety Information; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R.C.; Miller Mukherjee, I.R.; Malik, J.K.; Doss, R.B.; Dettbarn, W.-D.; Milatovic, D. Insecticides. In Biomarkers in Toxicology; Gupta, R.C., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 455–475. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, L.; Ge, C.; Feng, D.; Yu, H.; Deng, H.; Fu, B. Adsorption–desorption behavior of atrazine on agricultural soils in China. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 57, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, U.; Malik, M.; Javed, A. Pesticide exposure and human health: A review. J. Ecosyst. Ecogr. S 2016, 5, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Abouziena, H.F.; Omar, A.A.; Sharma, S.D.; Singh, M. Efficacy comparison of some new natural-product herbicides for weed control at two growth stages. Weed Technol. 2009, 23, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthil-Nathan, S. A review of biopesticides and their mode of action against insect pests. In Environmental Sustainability: Role of Green Technologies; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2014; pp. 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokesh, K.; Kanmani, S.; Adline, J.; Raveen, R.; Samuel, T.; Arivoli, S.; Jayakumar, M. Adulticidal activity of Nicotiana tabacum Linnaeus (Solanaceae) leaf extracts against the sweet potato weevil Cylas formicarius Fabricius 1798 (Coleoptera: Brentidae). J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2017, 5, 518–524. [Google Scholar]

- Tudi, M.; Daniel Ruan, H.; Wang, L.; Lyu, J.; Sadler, R.; Connell, D.; Chu, C.; Phung, D.T. Agriculture development, pesticide application and its impact on the environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengala, L.; Singh, N. Botanical pesticides—A major alternative to chemical pesticides: A review. Int. J. Life Sci 2017, 5, 722–729. [Google Scholar]

- Maghuly, F.; Laimer, M. Jatropha curcas, a biofuel crop: Functional genomics for understanding metabolic pathways and genetic improvement. Biotechnol. J. 2013, 8, 1172–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Singh, S.; Shukla, A.; Chaudhary, J. Evaluation of subacute toxicity of Jatropha curcas seeds and seed oil toxicity in rats. Indian J. 2014, 38, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Tomar, N.S.; Ahanger, M.A.; Agarwal, R. Jatropha curcas: An overview. In Physiological Mechanisms and Adaptation Strategies in Plants Under Changing Environment: Volume 2; Ahmad, P., Wani, M.R., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2014; pp. 361–383. [Google Scholar]

- He, W.; King, A.J.; Khan, M.A.; Cuevas, J.A.; Ramiaramanana, D.; Graham, I.A. Analysis of seed phorbol-ester and curcin content together with genetic diversity in multiple provenances of Jatropha curcas L. from Madagascar and Mexico. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2011, 49, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Herrera, J.; Ayala-Martinez, A.L.; Makkar, H.; Francis, G.; Becker, K. Agroclimatic conditions, chemical and nutritional characterization of different provenances of Jatropha curcas L. from Mexico. Eur. J. Sci. Res. 2010, 39, 396–407. [Google Scholar]

- Abobatta, W. Jatropha curcas: An overview. J. Adv. Agric. 2019, 10, 1650–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widiyastuti, T.; Sutardi, T.R. Amino acid and mineral supplementation in fermentation process of concentrate protein of jatropha seed cake (Jatropha curcas L.). Anim. Prod. 2016, 18, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Handique, G.; Barua, A.; Bora, F.R.; Rahman, A.; Muraleedharan, N. Comparative performances of jatropha oil and garlic oil with synthetic acaricides against red spider mite infesting tea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 88, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Group, P.-P. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Driel, M.L.; De Sutter, A.; De Maeseneer, J.; Christiaens, T. Searching for unpublished trials in Cochrane reviews may not be worth the effort. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 838–844.e833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, D.; Hernandez-Carreno, P.E.; Velazquez, D.Z.; Chaidez-Ibarra, M.A.; Montero-Pardo, A.; Martinez-Villa, F.A.; Canizalez-Roman, A.; Ortiz-Navarrete, V.F.; Rosiles, R.; Gaxiola, S.M.; et al. Prevalence, main serovars and anti-microbial resistance profiles of non-typhoidal Salmonella in poultry samples from the Americas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, 2544–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaidez-Ibarra, M.A.; Velazquez, D.Z.; Enriquez-Verdugo, I.; Castro Del Campo, N.; Rodriguez-Gaxiola, M.A.; Montero-Pardo, A.; Diaz, D.; Gaxiola, S.M. Pooled molecular occurrence of Mycoplasma gallisepticum and Mycoplasma synoviae in poultry: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, 2499–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amoabeng, B.W.; Gurr, G.M.; Gitau, C.W.; Nicol, H.I.; Munyakazi, L.; Stevenson, P.C. Tri-trophic insecticidal effects of African plants against cabbage pests. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingle, K.P.; Deshmukh, A.G.; Padole, D.A.; Dudhare, M.S. Screening of insecticidal activity of Jatropha curcas (L.) against diamond back moth and Helicoverpa armigera. Seed 2017, 5, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Mwine, J.; Ssekyewa, C.; Kalanzi, K.; Van Damme, P. Evaluation of selected pesticidal plant extracts against major cabbage insect pests in the field. J. Med. Plants Res. 2013, 7, 1580–1586. [Google Scholar]

- Devappa, R.K.; Angulo-Escalante, M.A.; Makkar, H.P.S.; Becker, K. Potential of using phorbol esters as an insecticide against Spodoptera frugiperda. Ind. Crops Prod. 2012, 38, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.S.; Silva, T.B.d.; Moraes, V.R.d.S.; Nogueira, P.C.d.L.; Costa, E.V.; Bernardo, A.R.; Matos, A.P.; Fernandes, B.; Silva, M.F.d.G.F.d.; Pessoa, Â.M.d.S. Chemical constituents of methanolic extracts of Jatropha curcas L. and effects on spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith)(Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Química Nova 2012, 35, 2218–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingle, K.P.; Deshmukh, A.G.; Padole, D.A.; Dudhare, M.S. Bioefficacy of crude extracts from Jatropha curcas against Spodoptera litura. Seed 2017, 5, 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Diabaté, D.; Gnago, J.A.; Koffi, K.; Tano, Y. The effect of pesticides and aqueous extracts of Azadirachta indica (A. Juss) and Jatropha carcus L. on Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Homoptera: Aleyrididae) and Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner)(Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) found on tomato plants in Côte d’Ivoire. J. Appl. Biosci. 2014, 80, 7132–7143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagdish, J.; Pillai, A.; Agnihotri, M. Field Efficacy of Jatropha Oil, NPV and NSKE against Helicoverpa armigera and Thysanoplusia orichalcea in Chickpea. Biopestic. Int. 2017, 13, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa-Brito, R.; Hernandez-Miranda, E.; Castrejon-Gomez, V. Biological Activity of Trichilia americana (Meliaceae) on Copitarsia decolora Guenée (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Entomol. Sci. 2019, 54, 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa-Brito, R.; Tabarez-Parra, A.S.; Avilés-Montes, D.; Rivas-González, J.M.; Ramos-López, M.Á.; Sotelo-Leyva, C.; Salinas-Sánchez, D.O. Chemical Composition of Jatropha curcas1 Seed Extracts and Its Bioactivity Against Copitarsia decolora2 under Laboratory and Greenhouse Conditions. Southwest. Entomol. 2021, 46, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Arévalo, H.; Pérez-Díaz, E.B.; Vásquez Vela, A.L.; Cerna-Mendoza, A.; Doria-Bolaños, M.S.; Arévalo-López, L.; Lopes Monteiro Neto, J.L.; Guerra-Arévalo, W.F.; Moreira-Sobral, S.T.; Abanto-Rodríguez, C. Control de larvas de Hypsipyla grandella Zéller utilizando resina de Jatropha curcas L. Acta Agronómica 2018, 67, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishag, A.; Osman, S.E.M. The Ovicidal Effect of Jatropha (Jatropha curcas) and Argel (Solenostemma argel) on Eggs of the Spiny Bollworm [Earias insulana (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)]. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Dev. 2020, 3, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, K. Effect of leaf extract of Jatropha curcas on growth and development of Bihar hairy caterpillar, Spilarctia obliqua, Walker. Int. J. Plant Prot. 2012, 5, 183–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kona, N.E.M.; Taha, A.K.; Mahmoud, M.E. Effects of botanical extracts of Neem (Azadirachta indica) and jatropha (Jatropha curcus) on eggs and larvae of tomato leaf miner, Tuta absoluta (Meyrick)(Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Persian Gulf Crop Prot. 2014, 3, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ugwu, J.A. Insecticidal activity of some botanical extracts against legume flower thrips and legume pod borer on cowpea Vigna unguiculata L. Walp. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2020, 81, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, H.; Santana, A.; Antigo, M. Insecticide activity of physic nut (Jatropha curcas L.) oil and neem (Azadirachta indica a. Juss.) oil on eggs of Diatraea saccharalis (Fabr.)(Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Arq. Do Inst. Biol. 2013, 80, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Khani, M.; Awang, R.M.; Omar, D.; Rahmani, M. Toxicity, antifeedant, egg hatchability and adult emergence effect of Piper nigrum L. and Jatropha curcas L. extracts against rice moth, Corcyra cephalonica (Stainton). J. Med. Plants Res. 2013, 7, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, G.N.; Faroni, L.R.A.; Sousa, A.H.; Freitas, R.S. Bioactivity of Jatropha curcas L. to insect pests of stored products. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2012, 48, 111–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babarinde, G.O.; Babarinde, S.A.; Ojediran, T.K.; Odewole, A.F.; Odetunde, D.A.; Bamido, T.S. Chemical composition and toxicity of Jatropha curcas seed oil against Sitophilus zeamais Motschulsky as affected by pre-extraction treatment of seeds. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 21, 101333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jide-Ojo, C. Extracts of Jatropha curcas L. exhibit significant insecticidal and grain protectant effects against maize weevil, Sitophilus zeamais (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). J. Stored Prod. Postharvest Res. 2013, 4, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukpai, O.M.; Ibediungha, B.N.; Ehisianya, C.N. Potential of seed dusts of Jatropha curcas L., Thevetia peruviana (Pers.), and Piper guineense Schumach. against the maize weevil, Sitophilus zeamais (Motschulsky, 1855) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) in storage of corn grain. Pol. J. Entomol. 2017, 86, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opuba, S.K.; Adetimehin, A.D.; Iloba, B.N.; Uyi, O.O. Insecticidal and anti-ovipositional activities of the leaf powder of Jatropha curcas (L.)(euphorbiaceae) against Callosobruchus maculates (F.)(Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Anim. Res. Int. 2018, 15, 2971–2978. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin Ii, R.O.; Abdulazeez, R.W. Comparative Efficacy of Neem, False Sesame and the Physic Nut in the Protection of Stored Cowpea against the Seed Beetle Callosobruchus maculatus (F.). Ethiop. J. Environ. Stud. Manag. 2013, 6, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolawole, A.O.; Kolawole, A.N. Insecticides and Bio-insecticides Modulate the Glutathione-related Antioxidant Defense System of Cowpea Storage Bruchid (Callosobruchus maculatus). Int. J. Insect. Sci. 2014, 6, S18029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pant, M.; Dubey, S.; Patanjali, P.K.; Naik, S.N.; Sharma, S. Insecticidal activity of eucalyptus oil nanoemulsion with karanja and jatropha aqueous filtrates. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2014, 91, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib-ur-Rehman; Mansoor-ul-Hasan; Ali, Q.; Yasir, M.; Saleem, S.; Mirza, S.; Shakir, H.; Alvi, A.; Ahmed, H. Potential of three indigenous plants extracts for the control of Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) and Rhyzopertha dominica (Fab.). Pak. Entomol. 2018, 40, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Onunkun, O. Evaluation of aqueous extracts of five plants in the control of flea beetles on okra (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench). J. Biopestic. 2012, 5, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Botti, J.M.C.; Holtz, A.M.; de Paulo, H.H.; Franzin, M.L.; Pratissoli, D.; Pires, A.A. Controle alternativo do Brevicoryne brassicae (Hemiptera: Aphididae) com extratos de diferentes espécies de plantas. Rev. Bras. De Ciências Agrárias 2015, 10, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Orozco-Santos, M.; Robles-González, M.; Hernández-Fuentes, L.M.; Velázquez-Monreal, J.J.; Bermudez-Guzmán, M.d.J.; Manzanilla-Ramírez, M.; Manzo-Sánchez, G.; Nieto-Ángel, D. Uso de Aceites y Extractos Vegetales para el Control deDiaphorina citriKuwayama en Lima Mexicana en el Trópico Seco de México. Southwest. Entomol. 2016, 41, 1051–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumantri, E.; Ratna, M.L.; Siregar, D.; Maimunah, F. Evaluation of potential plant crude extracts against green stink bug Nezara viridula Linn. (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae). Serangga 2019, 24, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Holtz, A.M.; Franzin, M.L.; Paulo, H.H.d.; Botti, J.M.C.; Marchiori, J.J.d.P.; Pacheco, É.G. Alternative control Planococcus citri (Risso, 1813) with aqueous extracts of Jatropha. Arq. Inst. Biol. 2016, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yadav, R.; Prasad, S.; Singh, S.K.; Vijay, V.; Sabu, T.; Lama, S.; Kumar, P.; Sandesh, J.; Thakur, A.; Ramawat, N. Bio-management of sugarcane aphid Melanaphis sacchari (Z.) in sorghum. Plant Arch. 2016, 16, 559–562. [Google Scholar]

- Ugwu, J.A. Prospects of botanical pesticides in management of Iroko gall bug, Phytolyma fusca (Hemiptera, Psylloidea) under laboratory and field conditions. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2021, 82, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, H.D.d.; Souza, M.d.D.d.C.; Giustolin, T.A.; Alvarenga, C.D.; Fonseca, E.D.; Damasceno, A.S. Bioatividade dos extratos aquosos de plantas às larvas da mosca-das-frutas, Ceratitis capitata (Wied.). Arq. Do Inst. Biol. 2015, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampadarath, S.; Puchooa, D.; Jeewon, R. Jatropha curcas L: Phytochemical, antimicrobial and larvicidal properties. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2016, 6, 858–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtz, A.M.; Marinho-Prado, J.S.; Cofler, T.P.; Piffer, A.B.M.; GOMES, M.d.S.; Borghi Neto, V. Insecticidal potential of physic nut fruits of different stages of maturation on Myzus persicae (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Idesia 2021, 39, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addisu, S.; Mohamed, D.; Woktole, S. Efficacy of botanical extracts against termites, Macrotermes spp., (Isoptera: Termitidae) under laboratory conditions. Int. J. Agric. Res. 2014, 9, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, E.; El Shafie, H. Insecticidal and Antifeedant Efficacy of Jatropha oil extract against the Desert Locust, Schistocerca gregaria (Forskal) (Orthoptera: Acrididae). Agric. Biol. J. N. Am. 2013, 4, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, E.M.; El Shafie, H.A. Toxicity, antifeedant and growth regulating potential of three plant extracts against the Desert Locust Schistocerca gregaria Forskal (Orthoptera: Acrididae). Am. J. Exp. Agric. 2014, 4, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gübitz, G.M.; Mittelbach, M.; Trabi, M. Exploitation of the tropical oil seed plant Jatropha curcas L. Bioresour. Technol. 1999, 67, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nukenine, E. Stored product protection in Africa: Past, present and future. Julius-Kühn-Arch. 2010, 26, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikal, W.M.; Baeshen, R.S.; Said-Al Ahl, H.A. Botanical insecticide as simple extractives for pest control. Cogent Biol. 2017, 3, 1404274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habou, Z.A.; Haubruge, É.; Adam, T.; Verheggen, F.J. Insect pests and biocidal properties of Jatropha curcas L. (Euphorbiaceae). A review. Biotechnol. Agron. Société Et Environ. 2013, 17, 604–612. [Google Scholar]

- Wongphalung, S.; Chongrattanameteekul, W.; Nhuiad, T. Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner)(Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) efficacy of crude extracts from physic nut, Jatropha curcas L. against the cotton bollworm, Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 47th Kasetsart University Annual Conference, Kasetsart, Bangkok, Thailand, 17–20 March 2009; pp. 562–570. [Google Scholar]

- Devanand, P.; Rani, P.U. Biological potency of certain plant extracts in management of two lepidopteran pests of Ricinus communis L. J. Biopestic. 2008, 1, 170–176. [Google Scholar]

- IPPC, S.; Gullino, M.; Albajes, R.; Al-Jboory, I.; Angelotti, F.; Chakraborty, S.; Garrett, K.; Hurley, B.; Juroszek, P.; Makkouk, K. Scientific Review of the Impact of Climate Change on Plant Pests—A Global Challenge to Prevent and Mitigate Plant Pest Risk in Agriculture, Forestry, and Ecosystems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, D.; Zaidan, I.; Dias, L.d.S.; Leite, J.; Diniz, J. Biocide potential of Jatropha curcas L. extracts. J. Biol. Life Sci. 2020, 11, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, I. New concept to search for alternate insect control agents from plants. Adv. Phytomed. 2006, 3, 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kodjo, T.A.; Gbénonchi, M.; Sadate, A.; Komi, A.; Yaovi, G.; Dieudonné, M.; Komla, S. Bio-insecticidal effects of plant extracts and oil emulsions of Ricinus communis L. (Malpighiales: Euphorbiaceae) on the diamondback, Plutella xylostella L. (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) under laboratory and semi-field conditions. J. Appl. Biosci. 2011, 43, 2899–2914. [Google Scholar]

- Sisodiya, D.; Shrivastava, P. Repellent and antifeedant activities of Euphorbia thymifolia (Linn.) and Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) against Rhyzopertha dominica (Fab.). Int. J. Res. Anal. Rev. 2018, 5, 257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Kavallieratos, N.G.; Athanassiou, C.G.; Arthur, F.H. Effectiveness of insecticide-incorporated bags to control stored-product beetles. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2017, 70, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Shi, J.; Mu, Y.; Tao, K.; Jin, H.; Hou, T. AW1 neuronal cell cytotoxicity: The mode of action of insecticidal fatty acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 12129–12136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, J.H.; Mon, T.; Hendrickson, T.L.; Mitchell, L.A.; Grant, D.F. Defining mechanisms of toxicity for linoleic acid monoepoxides and diols in Sf-21 cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001, 14, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balshem, H.; Helfand, M.; Schunemann, H.J.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Vist, G.E.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Meerpohl, J.; Norris, S.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Acronym | Definition | Search Term |

|---|---|---|

| (P) Population | We included studies that reported results on the use of botanical extracts from the plant J. curcas in which their bioactivity was assessed either as insecticidal or insectistatic against insect pests of different crops | Jatropa curcas OR J. curcas OR physic nut |

| (I) Intervention | We included studies that assessed any type of botanical extract (including hexanic, acetonic, methanolic, aqueous, ethanolic, or petroleum ether, among others) or secondary metabolite extracts from the plant J. curcas under in vitro, field, or greenhouse conditions | extracts OR botanical extracts OR hexanic OR acetonic OR methanolic OR aqueous OR ethanolic OR petroleum ether OR secondary metabolites |

| (O) Outcome | The studies should include at least one of the following outcomes: Insecticidal activity, considered as the primary outcome and defined as the control of the number of insects or colonies reported as the absolute value or percentage of mortality or larval and pupal viability reduction after exposure to the botanical extracts Insectistatic activity, considered as the secondary outcome and defined as an effect on the growth or reproduction of the insect, anti-feeding effect, including a reduction in larval and pupal weight, lower fecundity and fertility, anti-oviposition effect, reduced hatching and hatchability of eggs, altered development, morphological malformations, and altered physiology | crop pest insects OR insect control OR insecticide OR insectistatic OR bioactivity |

| (S) Study | We included only primary experimental studies published from 2012 to 2022 the last 10 years as full text articles in English, Spanish, or Portuguese in peer-reviewed journals. We excluded all nonpublished evidence (gray literature) to ensure optimal methodological comparability [29] |

| Activity/Botanical Extract | Affected Crop or Grain | Treatment | Main Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insecticidal activity | |||

| (1) Aqueous seed extract | Stored grains | 10% (w/v) | 60–100% mortality of S. zeamais, R. dominica, and T. castaneum |

| Eucalyptus | 20 to 35% (w/v) | 100% mortality of Macrotermes spp. | |

| Stored grains | 300 and 1500 ppm | 88–100% mortality of T. castaneum | |

| Soybeans | 0.25% (v/v) | 100% mortality of N. viridula | |

| Okra | 10% (w/v) | 64% reduction in the populations of P. uniforma and P. sjostedti | |

| (2) Seed oil | Corn | 20 mg/mL−1 phorbol esters | 80% mortality of S. frugiperda |

| Coffee | 1 and 4% (v/v) | 76.3 and 92.5% reduction in the nymphal number of D. citri | |

| Stored grains | 200 μL/L | 84% mortality of S. zeamais | |

| Cabbage | 2.5% (v/v) | 61–71% mortality of M. persicae | |

| Cabbage | 3% (v/v) | 60% mortality of B. brassicae | |

| (3) Methanolic seed extract | Cabbage | 5% (w/v) | 100% mortality of P. xylostella |

| (4) Petroleum ether seed extract | Rice, corn, cocoa, and coffee | 20 µL/mL | 98% mortality of C. cephalonica |

| (5) Methanolic leaf extract | Sorghum | Amla + Drumstick + Jatropha + Neem + Water (1:1:1:1:1) | 68% mortality of M. sacchari |

| Cotton, rice, tobacco | 5% (w/v) | 60% mortality of S. litura | |

| Corn | 1000 mg/kg−1 fresh and dried leaves | 60 and 56.67% larval mortality of S. frugiperda | |

| (6) Aqueous leaf extract | Cabbage | 3% (w/v) | 66% mortality of P. xylostella and reduced infestation of B. brassicae |

| Cowpea | 1% (w/v) | 98% mortality of C. maculatus | |

| Fruit | 10% (w/v) | 95.6% mortality of C. capitata | |

| Insectistatical activity | |||

| A. Development | |||

| (1) Seed oil | Gramineae and legumes | 10% (v/v) | Delayed nymphal instar development by 5 days in S. gregaria |

| B. Eggs | |||

| (1) Aqueous leaf extract | Cowpea | 1% (w/v) | 81.04% reduction in oviposition rate in C. maculatus |

| (2) Aqueous seed extract | Okra | 20% (w/v) | 64% decrease in hatchability of eggs in E. insulana |

| (3) Seed oil | Stored grains | 100 ppm | Inhibited 90% oviposition and reduced 92.3% hatching in S. zeamais |

| Gramineae and legumes | 10% (v/v) | 42.2% reduction in female fecundity in S. gregaria | |

| Sugar cane | 3% (v/v) | 40% decrease in egg hatching in D. saccharalis | |

| (4) Petroleum ether seed extract | Rice, corn, cocoa, and coffee | 2 µL/mL | 58% decrease in hatchability in C. cephalonica |

| C. Anti-feeding | |||

| (1) Seed oil | Corn | 0.125 mg/mL−1 phorbol ester enriched fractions | 45% reduction in relative consumption rate in S. frugiperda |

| Corn | 0.25 mg/mL−1 phorbol ester enriched fractions | 42% decrease in relative growth in S. frugiperda | |

| Gramineae and legumes | 5% (v/v) | 50–78.92% anti-feedant effect on S. gregaria | |

| (2) Methanolic leaf extract | Cotton, chickpea | 15% (w/v) | 42% reduction in larval weight in H. armiguera |

| (3) Petroleum ether seed extract | Rice, corn, cocoa, and coffee | 6 µL/g | 48.08% anti-feedant effect on C. cephalonica |

| D. Malformations in adult insects | |||

| (1) Acetonic seed extract | Cabbage | 500 ppm | 60% deformed insects of C. decolora |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valdez-Ramirez, A.; Flores-Macias, A.; Figueroa-Brito, R.; Torre-Hernandez, M.E.d.l.; Ramos-Lopez, M.A.; Beltran-Ontiveros, S.A.; Becerril-Camacho, D.M.; Diaz, D. A Systematic Review of the Bioactivity of Jatropha curcas L. (Euphorbiaceae) Extracts in the Control of Insect Pests. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11637. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511637

Valdez-Ramirez A, Flores-Macias A, Figueroa-Brito R, Torre-Hernandez MEdl, Ramos-Lopez MA, Beltran-Ontiveros SA, Becerril-Camacho DM, Diaz D. A Systematic Review of the Bioactivity of Jatropha curcas L. (Euphorbiaceae) Extracts in the Control of Insect Pests. Sustainability. 2023; 15(15):11637. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511637

Chicago/Turabian StyleValdez-Ramirez, Armando, Antonio Flores-Macias, Rodolfo Figueroa-Brito, Maria E. de la Torre-Hernandez, Miguel A. Ramos-Lopez, Saul A. Beltran-Ontiveros, Delia M. Becerril-Camacho, and Daniel Diaz. 2023. "A Systematic Review of the Bioactivity of Jatropha curcas L. (Euphorbiaceae) Extracts in the Control of Insect Pests" Sustainability 15, no. 15: 11637. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511637

APA StyleValdez-Ramirez, A., Flores-Macias, A., Figueroa-Brito, R., Torre-Hernandez, M. E. d. l., Ramos-Lopez, M. A., Beltran-Ontiveros, S. A., Becerril-Camacho, D. M., & Diaz, D. (2023). A Systematic Review of the Bioactivity of Jatropha curcas L. (Euphorbiaceae) Extracts in the Control of Insect Pests. Sustainability, 15(15), 11637. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511637