1. Introduction

A long-standing concern in gender scholarship is how well women are represented in democratic institutions [

1]. Research indicates that the unequal representation, as well as the absence of women in leading positions, may result in women’s preferences being under-represented in agenda setting and in political decisions [

2,

3]. The role of gender in political leadership and decision-making has been analysed by scholars in several different fields. Gender-equal representation has been discussed in terms of its differential impact on policy, as substantive representation, and in relative terms as a critical mass, or as gender quotas [

4,

5]. Several concepts offer explanations for why women are unequally represented in political leadership, e.g., glass walls, leaking pipelines, and the glass ceiling [

6]. Women tend to be underrepresented in higher positions of the political hierarchy and are less likely to be found in prestigious posts [

7,

8]. This is regardless of whether the person is an elected representative of a party [

9,

10]. Many scholars conclude, in line with Celis and Childs [

1] (p. 28), that “political institutions privilege a masculinized political agenda and reproduce gendered norms”.

This paper takes a comprehensive view of gender equality in the leadership functions in three local sites of political influence in Sweden: local committees taking decisions within the area of transport, the local City Board, and the City Council. This study aims to examine whether there is a discernible trend and disparity in female representation across various bodies, particularly in leadership positions, while accounting for political party affiliation. In this paper, we also ask whether women in leading positions increase the likelihood of also having women in positions at lower levels, and especially whether women having the position of chairperson of the City Board influences the gender of the chairperson in other bodies.

The study was conducted for municipalities in Sweden and is based on a unique dataset collected in this study. Although statistics for the local level have previously been analysed for chairpersons in Sweden, e.g., Folke and Rickne [

11] and Statistics Sweden [

12], there are still few studies or datasets that capture the whole presidium, including the first and second vice chairperson. This study thus contributes to the research area by using a dataset with detailed information that enables representation per position analyses.

According to Homsy and Lambright [

13], there is a growing body of research examining factors associated with gender in local government practices [

14,

15], but little is known about the influence of characteristics of the leaders of these bodies. Further, research has shown that factors such as the use of networking and affinity bias (the tendency for individuals to favour people who share similar characteristics or interests) contribute to the dominance of men in leading positions [

16], and also at the local level of politics [

17]. With an increasing share of female representation, it is also of interest to study whether the opposite applies, but so far there is a lack of these types of studies.

Much of the adjustment needed to reduce Sweden’s emissions from transport must take place with the help of efforts at regional and local levels. Thus, Sweden’s municipalities have an essential role. One of the municipality’s most important planning tools is the land development plan (Översiktsplaner), as this plan provides guidance for how land and water areas should be used, preserved, and developed in the longer term in each municipality. This document may also be argued as giving the basic conditions for future transport infrastructure planning [

18,

19]. Within the area of urban planning and transport, municipalities take decisions on, e.g., parking strategies, the design of local streets, maintenance, and measures for sustainable travel.

As concluded in previous work [

20], the transport area is, in the context of Sweden, comparatively unequal regarding the historic domination of men in decision-making and leadership. At the same time, it is important to reach set climate objectives and a sustainable and decarbonized transport system, and since it has been demonstrated widely that women show behaviours, preferences, and attitudes more in line with a climate agenda [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25], female leadership in the transport sector is desirable.

The paper is structured as follows. It starts with a background section presenting research on gender inequalities, representation, and leadership in local politics in Sweden, which constitutes a base for the study outline. Thereafter, the results are presented and the paper ends with a discussion on the implications of the result for a more sustainable transport system.

2. Gender Inequalities, Representation, and Leadership in Local Politics in Sweden

This section presents the relevant literature and spells it out in terms of how gender equalities in representation and leadership can be explained, and presents what previous studies have shown about gender inequalities in the transport sector, for local politics, and particularly for Sweden. In doing so, it points to the research gaps that this study contributes to.

Several different concepts offer explanations for why men and women are unequally represented in political leadership, e.g., glass walls, leaking pipelines, and glass ceilings [

6]. The term “glass walls” [

26] is used to refer to invisible horizontal segregation ‘walls’ within an organization, where women end up in sectors or in functions, e.g., administrative roles, where the chances of career advancement are low. The term “the leaking pipeline” [

27] denotes when more women leave their professional careers during the early stages and ‘leak’ from the career hierarchy, and thus there are fewer female than male candidates available when higher positions are to be filled. The term glass ceiling is used to describe how women are more disadvantaged than men the higher up they go in an organization, which makes it more difficult for women to reach the highest positions. Cotter et al. [

28] suggest that there is a glass ceiling when there is an unequal representation between the sexes that cannot be explained by other factors, that the inequality between the sexes increases with higher hierarchical levels, that there are circumstances that make advancement more difficult for women, and that inequality increases over time during the career. One factor put forward is that we tend to prefer people who are similar to ourselves. Within the area of politics, this has been shown to be a factor influencing women’s representation, e.g., Crowder-Meyer [

29] and Fox and Lawless [

30]. Research by Niven [

17] indicates that party chairs consistently preferred candidates more like themselves when analysing county party chairs and a sample of locally elected women from four states in the US.

Female political status is measured in various ways, as the percentage of women serving in legislative bodies or committees affiliated with those bodies, or as the percentage of women in administrative policymaking positions [

20,

31]. The concept of representation includes both the number and the political status/power of the representation [

32]. Sweden is often described as a pioneering country when it comes to gender equality representation, and since the 1990s more than 40 per cent of the members of the parliament have been women and the governments have been largely equal numerically [

33]. The country has implemented gender mainstreaming as a policy approach to actively promote and achieve gender equality [

34], and has gained recognition for its notable performance on gender indexes, including the EU Gender Equality Index [

35]. Since the 2014 Swedish elections, when all parties used some form of quota [

5] there have been no formal quotas but, normally, an aspiration among parties to strive for equal representation. Studies show the effect of gender quotas and an increasing share of women in parliaments [

5,

36]. The notion of ‘critical mass’ suggests that a certain threshold of women’s representation is necessary to bring about a significant impact on policies [

37]. Dahlerup [

4] proposed a minimum of 40% representation for influencing policy-making, but it is probable that this effect has diminished over time due to the increased prevalence of equality policies throughout the entire political spectrum. However, Bäck and Deus’ [

38] analysis of speechmaking among members of parliament in seven European countries (incl. Sweden) shows that female members of parliament take the floor less often when they are members of parties with high shares of female representatives, contradicting the critical mass theory.

A focus on only the share of female bodies obscures how power and influence relate to positions in an organizational hierarchy. The conditions for achieving and exercising leadership are not equal for men and women, and the gender inequality problems of political leadership remain relevant and women seem to have more difficulty in advancing to ministerial posts than men [

39]. Sweden had to wait until 2021 to have its first female prime minister. Patterns of gender inequality also prevail at the local level. A mapping of representation in local committees that make decisions on transport-related issues [

20,

40] showed that women’s representation in Swedish municipal committees has increased over the last 15 years, even though it is still far from equal. Compared with the City Council and City Board, the committees are much less equal. Men are overrepresented in municipal committees, such as on technical and building committees, and similar ones where transport planning and decisions are made [

20]. This is in line with what other studies have shown on representation in the Scandinavian transport sectors [

31], and also including the EU [

41], in which transport issues are the domain of men.

Folke and Rickne [

11] tested whether a glass ceiling existed for female municipal politicians elected from 1988 to 2010 in Sweden. Three levels were compared: ordinary elected members of the City Council, and chairpersons of the City Board and Council. The study shows that the underrepresentation of women in higher positions cannot be explained by the lack of female candidates or by the women who are at lower political levels lacking relevant qualifications. However, women in the sample made up 48 per cent of the elected members, 38 per cent of the chairpersons of committees, and 28 per cent of the chairperson of the City Board. The study shows that women are more disadvantaged the higher up they go in the hierarchy, and that the gender difference is greatest when it comes to the last political career step.

Other research suggests that political party affiliation may have relevance for gender-equal representation; for instance, parties with leftist ideologies favour equal representation and gender quotas and are more likely to appoint female leaders [

42,

43].

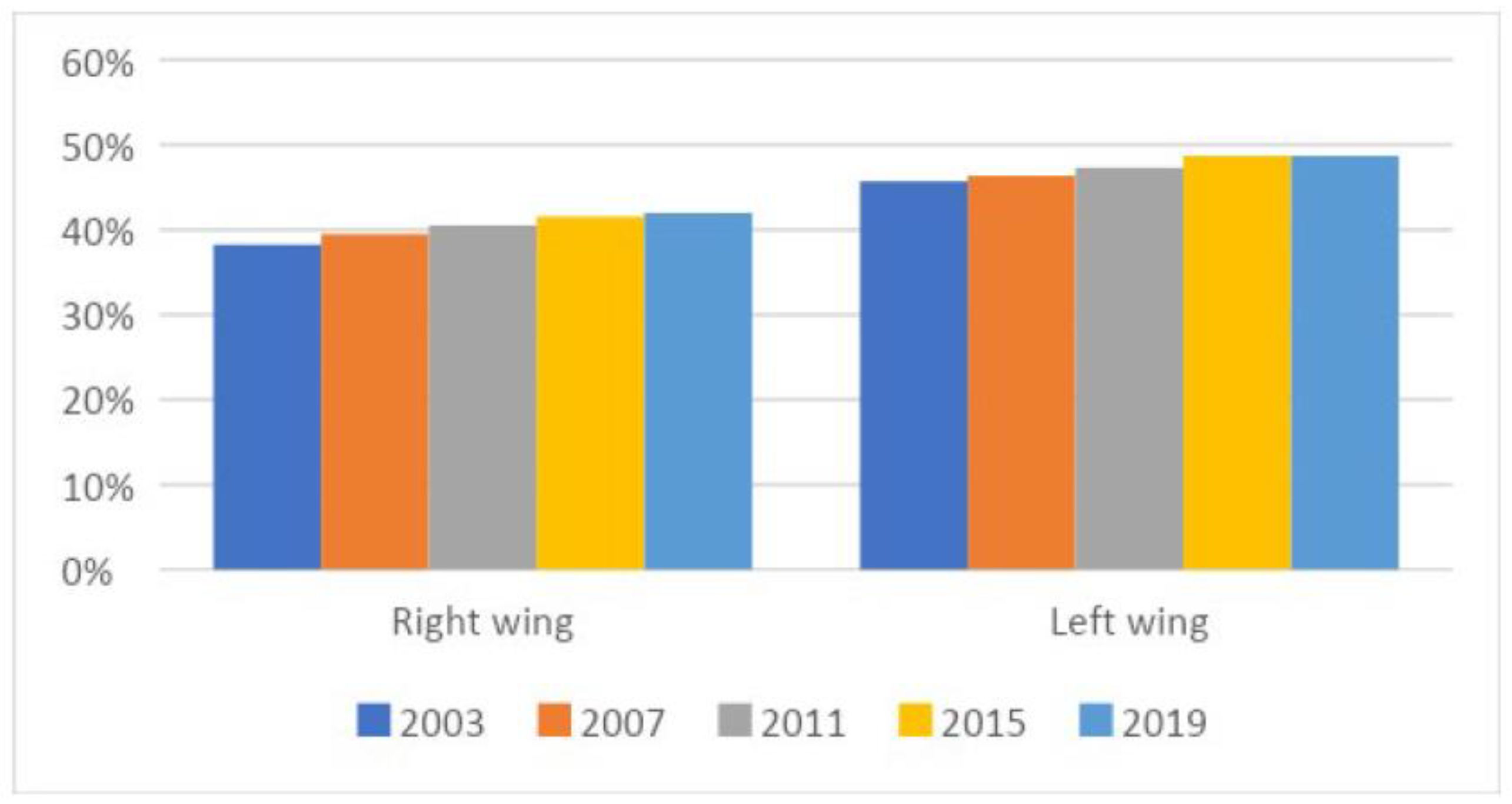

Figure 1, below, shows that this is the case for Sweden. The share of women in elected local assemblies is higher for left-wing parties (Social Democrat party, Leftist party, Green party). On the other hand, this was contradicted in Folke and Rickne’s [

11] analysis of locally elected persons after the elections of 2006 and 2010; they showed that the proportion of women decreased dramatically over that period, including in the leadership positions of the parties (both left- and right-wing parties).

The literature review indicates, altogether, a knowledge gap regarding representation in leading positions at the local level in Sweden. We will now continue by investigating a dataset consisting of individuals in presidiums of various bodies at the municipal level.

3. Local Government in Sweden: Method and Data

The material for this study was derived from local governments in Sweden. These local governments have far-reaching autonomy, which is enshrined in the constitution. The municipalities must comply with the framework set by the parliament and the government, but this autonomy gives each municipality the right to make independent decisions and, e.g., levy taxes on its inhabitants [

18]. The City Council is the local parliament directly elected by citizens. The City Board is the local government, often based on a coalition between the parties with the most council seats. The chairperson of the City Board (considered the main leader of the municipality) is appointed by the largest party in the governing coalition after the general election, and the remaining board seats are distributed among all parties according to the number of seats they hold in the full assembly. Boards and Councils are responsible for the broader political decisions in the municipalities. The municipalities decide which committees they want, resulting in a varying organizational structure. The Council decides which committees should be present, and thus decide the organizational structure. A committee receives its mission from the Council and is responsible for a specific area, such as health, schools, buildings, and transport. They are responsible for the daily operations of the municipality, including preparing matters for the Council’s decision-making and implementing Council decisions. The committees are empowered to make decisions on minor issues, as defined by the Council [

18,

19]. The leadership of the committees consists of a presidium, with a chairperson, a first vice and usually a second vice chairperson [

12]. All positions within the City Board and the committees are appointed by the local parties by the rank order of the electoral ballot.

The analysis of political status connected to female representation was operationalized through a comparison of female representation (female share) in various positions in the presidiums of studied bodies. The analysis of power was carried out under the assumption that different positions are connected to different political statuses. The position as chairperson is assumed to be connected to higher political status compared to the first vice chairperson, and even higher compared to the second vice. Further, it is assumed that the position as the chairperson of the City Board is assumed to be connected to higher political status than the chairperson of the City Council.

In this study, we also analysed differences in political status between men and women by studying the association between the gender of a person in a higher position and the gender of a person in a lower position (a vertical relationship). We focused on whether the association is significantly different depending on the gender of the person in the higher position.

Odds ratios were used to analyse the strength of the association between gender representation in different positions within and between bodies. The odds ratios were calculated as the ratio of the odds of an event occurring in one group to the odds of it occurring in another group, see, e.g., Persoskie and Ferrer [

44]. Due to small sample sizes, Fisher’s Exact Probability test was used to test whether the odds ratios were equal to 1 or not (i.e., no association). Finally, in order to analyse the trends in representation and political status, statistics for two years were compared.

The sampling frame of the survey consisted of all 290 municipalities in Sweden, and for this study unique data on representation and party affiliation for chairpersons (chairperson, first vice, and second vice chairperson) at committees, City Boards, and Councils for 2011 and 2015 were gathered and added from the municipalities through documents found on websites and contacts through email and telephone when documentation on websites could not be found. In municipalities in Sweden, there are often different committees in a municipality that take decisions related to the transport area. For these municipalities, the data of gender representation are not a binary number (man/woman) for a specific position in transport-related committees, but instead the share of men/women in the studied position.

For some municipalities, it was not possible to retrieve the information despite several attempts and reminders directed to local administrators. For representation in presidiums of transport-related committees, there was an initial limitation in the number (as identified in Winslott Hiselius et al. [

20]) based on difficulties identifying the transport-related committees in the years 2011 and 2015. However, an analysis of the municipalities lacking in the dataset gave no indication of bias regarding geography, size, population, etc. The data collection process encompassed the years 2011 and 2015, allowing for the integration of this data with an existing dataset from a previous study. This merger resulted in a larger pool of information for analysis. In order to illustrate the size of the dataset in the following Tables, the total number of observations (total number of persons) is consistently presented along with the figures on the female share.

For the analysis, the bodies studied within each municipality were treated as distinct entities. Missing data for one body did not lead to the exclusion of data pertaining to other bodies in the analysis. This approach was chosen due to our focus on analysing different bodies rather than different municipalities. Only when examining the associations between bodies were the City Council and City Boards considered as a collective entity for each municipality.

5. Concluding Discussion

The results of this study indicate that when looking at the local leadership (the presidiums) of various bodies, there is a democratic problem regarding the representation of women in transport-related municipal decision-making, and that representation is unequal when analysing leadership roles. Through a unique dataset, we studied representation in leadership roles and found it to be unequal, with a generally low share of women in the presidiums. We also found a tendency to exclude women from leadership positions as chairperson (especially of City Boards), a position considered to be the most influential position of a municipality [

12]. There was also a greater tendency to have a man as vice chairperson when a woman is a chairperson than the reverse. In this paper, we could thus identify various aspects of gender gaps at the local political level (either termed leaky pipeline or glass ceiling) when analysing different posts within presidiums, but also for the position as the chairperson of the City Board. When analysing a vertical relationship, i.e., if the gender of the person in the top post (chairperson of City Board) is associated with the gender of other posts in the presidiums, the result revealed a somewhat weaker association and indicated that aspects like affinity do not play out. This may also be a result of the way positions are appointed, based on a nomination by a party and not recruitment by the person with the most influential position. Our findings align with previous studies conducted on local representation in Sweden [

20], as well as within the Scandinavian transport sectors [

31], which have highlighted the prevalence of masculine dominance in the transport industry. Similarly, our study revealed a significant gender disparity, particularly in the highest political positions, corroborating the findings of Folke and Rickne [

11]. Additionally, our results are consistent with research by Goodard [

43] and others, indicating that political parties with left-leaning ideologies tend to prioritize gender equality and are more inclined to appoint female leaders.

So, what are the implications of the result of this study on sustainable transport policies and measures mitigating climate change? The low representation of women in committees taking transport-related decisions supports the notion that the transport area is masculinized. The underrepresentation of women suggests that prevailing practices, planning, and structures prioritize other factors over the inclusion of women and the unique perspectives they offer [

45]. Thus, as Celis and Childs [

1] suggest, these are political institutions that privilege a masculinized political agenda and through it reproduce certain gender norms. Masculinized norms of technical solutions and infrastructure investments tend to overshadow alternative ideas [

40]. This masculinized agenda may make it difficult for women to articulate diverging norms or alternative views. Also, in other sectors, representation is not enough to include a stronger gender equality perspective.

The discrepancy between men’s and women’s representation in leading positions that has been identified in this study through the gender share of the members of the bodies is close to equal and may be seen as a challenge since decisions on the local level are indicated to be important for sustainability [

40]. Gender-equal representation may be relevant to increasing energy efficiency, as there are large discrepancies along the lines of gender in pro-environmental behaviour and travel patterns, as well as in attitudes and norms among citizens, planners, and decision-makers [

25,

46,

47]. Women thus have behaviour, preferences, and attitudes more in line with a climate agenda, which makes their leadership desirable when climate change is to be tackled. The findings of these studies regarding gender differences in behaviour and attitudes indicate that if women were equally represented in policymaking and held equal influence in decision-making processes (including higher positions), the gender differentials observed would likely influence the outcomes of those decisions. Higher female representation in leading positions may also result in even more women in higher positions. As, e.g., critical mass theory suggested, there needs to be a certain volume to change norms and values.

The pressing time for policies mitigating climate change suggests that low gender equality is not “just” a democratic problem if we think that gender equality also could support more sustainable development. A question that might be asked is what representation measured as the percentage of women per body or presidium means? The results indicate that a focus on representation through the share of women out of total representatives in a body or of the presidium can simplify the question of gender equity and representation in local democratic institutions. There is a need to identify and follow up considering the degree of influence and power, as well.