Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic brought unprecedented challenges to the education sector, forcing schools at a worldwide level to quickly adapt their activities to remote learning. Despite the obstacles and challenges, the pandemic also represented an opportunity for reflection and innovation in education. A survey with 558 teachers from primary and middle schools in several regions of Italy was carried out to analyse challenges and lessons learned by Italian schools, aiming to improve the quality of digital education. The lessons learned highlighted the importance of developing strategies to address challenges such as the necessary infrastructure, digital skills, student engagement, collaboration, and personalised online learning. On the one hand, government-initiated interventions, like the National Recovery and Resilience Plan, aim to bridge the digital divide and improve education quality. On the other hand, the potentialities of immersive technologies like the Metaverse can provide exciting opportunities for interactive and engaging learning experiences, encouraging interaction and collaboration among students.

1. Introduction

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic created a global crisis that impacted all sectors of society, including education. Nearly every student in the world was affected, and several countries temporarily closed their schools and adopted remote learning as an alternative [1]. Italy, like many other countries, faced significant disruptions to its educational system, as schools and universities were forced to close their doors to avoid the spread of the virus. This emergency forced Italian educational institutions to quickly adapt their methodologies to online learning, utilising online platforms and digital tools to deliver instruction. The resulting shift to remote learning posed several challenges, including issues related to access to the necessary technologies and the need for teachers and students to adapt to new approaches and models of instruction. Amid the challenges, however, the pandemic also represented an opportunity for reflection on the urgent need for innovative approaches to education. The negative effects caused by the COVID-19 pandemic forced all to search for new solutions triggering innovation processes, and “this crisis has stimulated innovation within the education sector” [2]. The pandemic has shaken up traditional teaching methods, accelerating the adoption of new technologies and innovative teaching methods [1]. This trend is likely to continue, with schools continuing to explore new ways of using technology to enhance learning. From this perspective, it is crucial to reflect on the lessons learned from this experience and to envision the future of education by rethinking teaching and learning with new digital tools. This includes addressing the challenges faced during the pandemic, such as the digital divide, inequitable access to resources, and the need for effective strategies to promote student engagement and well-being in remote learning environments. It also involves leveraging the advancements in educational technology and exploring innovative teaching methods and tools that can enhance the learning experience and foster a more inclusive and resilient education system. This study is guided by one main research question and three sub-questions:

What lessons have been learned by schools during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- -

- What are teachers’ expectations in terms of priority intervention policies?

- -

- How are policies for digital transition changing the educational system in Italy?

- -

- What are the potentials and perspectives of the Metaverse in education?

Although there are several studies on education during the COVID-19 pandemic, they are currently limited studies on how Italian education is changing or is expected to change in the future. This article investigates the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Italian primary and middle schools in the future of education.

2. Review of the Research Literature on Obstacles to the Adoption of Technology in Education

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the adoption of technology in education, but while online learning became a crucial alternative to ensure the continuity of education during the crisis, the sudden shift to remote learning posed numerous issues and obstacles for students, educators, and institutions alike. Different studies in the literature (described in the following subsections) analysed the obstacles and challenges of online learning during this period.

2.1. Lack of Equitable Access to Technology

One of the primary obstacles was the lack of equitable access to technology and Internet connectivity to access and participate in digital learning activities [3]. Many students, especially those from low-income families or rural areas, faced difficulties in accessing the technology required for online learning, such as computers, laptops, reliable Internet connections, digital learning materials, parental support, and suitable learning environments [4,5]. This digital divide increased existing educational inequalities, making it challenging for some students to fully participate in remote learning activities and access educational resources. It is essential to ensure that all students have access to digital tools, as the digital divide can exacerbate educational inequalities [2].

2.2. Lack of Digital Skills

The integration of digital technologies also had significant implications for teachers. The rapid shift from traditional to online learning imposed by the pandemic emergency found schools unprepared. Many teachers and students had to quickly adapt to unfamiliar online platforms, digital tools, and communication technologies. The transition to online learning required teachers to develop new skills in their virtual teaching, create engaging online content, and provide technical support to students [6]. Similarly, students had to learn how to navigate online learning platforms, submit assignments electronically, and effectively communicate with their teachers and peers in virtual settings. Although teachers tried to be resilient, they often worked without adequate tools and methods, and this increased their workload and stress in developing and delivering digital content, mainly if they had limited experience with online teaching [7]. This made clear that teachers need to be trained in using digital tools effectively through training courses and guidelines [8,9,10]. Without proper training, teachers may struggle to use digital tools effectively, leading to a negative impact on students’ learning outcomes. Providing access to technological resources and investing in training and support for both students and instructors can significantly improve the effectiveness of distance learning [11].

2.3. Students’ Engagement and Motivation

Another obstacle faced during the pandemic was represented by the need to keep students engaged and motivated when using remote learning environments. The absence of face-to-face interaction, peer collaboration, and physical classroom dynamics presented challenges in fostering active participation and meaningful learning experiences. Students experienced increased feelings of isolation, reduced social interactions, and a potential decline in their overall motivation and well-being [7]. Furthermore, some students had difficulties understanding the material delivered online; primary school students sometimes felt bored and were less active and interested in participating during the distance learning process [12,13]. For this purpose, some studies suggested the use of interactive and multimedia materials (animations, images, games) to increase students’ motivation [14,15]. Virtual-reality technology and gaming tools can be effectively used to achieve a high level of engagement and to foster attention, interaction, and collaboration among students [16]. Some schools successfully used gamification to increase students’ motivation [17] and a cooperative learning approach [18,19]. Incorporating interactive learning activities and promoting social interaction can significantly enhance student engagement and motivation in online learning environments [20]. It is necessary to support a culture of innovation, rethinking digital learning as a digital ecosystem in which each actor is proactive and responsive, creating an open collaborative environment and fostering cooperative relationships [21].

2.4. Lack of Assessment Methods

Another important obstacle to the pedagogical level was online assessment. Traditional methods of assessment, such as in-person exams, have been difficult to replicate in an online environment. One of the main challenges was represented by the lack of any student feedback and evaluation systems [9,22]. Teachers had to explore alternative assessment strategies that could effectively measure student learning levels and provide timely feedback in a remote setting. Some studies revealed the need to develop a safe, valid, and reliable online assessment system [23,24]. Finally, digital learning should be integrated into the curriculum in a way that complements traditional teaching methods rather than replacing them [25]. It is, however, necessary to differentiate between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Emergency remote teaching was the quick shift to online learning due to the pandemic, while online learning is a well-designed, interactive, and engaging experience for learners [26]. Therefore, to ensure the effectiveness of online learning, careful planning and design are necessary.

2.5. Lessons Learned

Several different studies post-pandemic analysed lessons learned during online learning. A Lobos study [27] stated that successful practices introduced during online learning should be incorporated into educational policies and learning processes. Lessons learned from university are, in fact, that new learning scenarios should consider specific pedagogical practices, including active, collaborative, meaningful, problem-based strategies, and a diversity of feedback practices. Furthermore, resources and activities should be associated with visual attractiveness, interactivity, and gamified materials. According to Singh et al. [28], COVID-19 should be considered as an opportunity which allowed for the critical analysis of current practices and re-envision existing academic processes. Among lessons learned from high education systems, the study highlighted the need to invest in faculty development in integrating technology to facilitate and enhance education and innovative teaching and learning practices. Similarly, the study of Munir [29], among the recommendations for post-pandemic education, includes the unified selection of digital learning tools across courses, a designated budget for digital learning tools, training support, and hybrid learning methods. The study proposes the implementation of blended and hybrid learning approaches to enhance higher education at the university level. It emphasises the crucial role of digital tools in mitigating communication barriers experienced by students. Among post-pandemic reflections, lessons from Chinese mathematics teachers indicate the need to enhance the integration of technology in instructional practices, redefine the dynamics of teacher–student interactions, and reorganise teaching methodologies in traditional classroom settings [30]. However, an important issue to consider is that in the post-pandemic environment, learning styles could be different due to the lack of mobility restrictions. For example, Gonzales et al.’s [31] study found that students shifted towards a more distributed type of learning during the pandemic, moving away from their dependence on intermittent, deadline-driven activities. This change in learning style may not persist as a consistent pattern in the post-pandemic era. Therefore, teachers should consider this issue in the organisation of work activities and their response to students’ approach to learning.

This study contributes to the extant literature by analysing lessons learned in primary and middle schools.

3. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in Italy two years after the pandemic to analyse the faced obstacles during online learning, the lessons learned from this experience, and propose some intervention policies to overcome the open challenges.

The COVID-19 pandemic was considered a source for learning and a national survey was carried out. The study used a quantitative methodology; data were gathered via an online survey using a structured questionnaire (see Supplementary Material). Some Italian cities were selected to participate in the study, including the various Italian geographical locations of Italy (north east, north west, centre, south, and islands). In particular, the cities of involved schools were Turin, Padua, Milan, Rome, Viterbo, Reggio Calabria, Palermo, Nuoro, and Cagliari. This selection was made to include in the study both schools with students from urban and rural areas. The sample of the study included Italian teachers of primary and middle schools, coming from different ages, genders, and subject matters. The characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. Primary and middle school teachers were chosen because, while there are many studies on high schools, few studies have focused on elementary and middle school children who have had to face greater challenges given their age. To qualify participants in the study, they were requested to be primary or middle school Italian teachers and have actively used online teaching during the pandemic period. For the sample selection, a convenience sampling method was used [32], so the probability of selecting each sample from the population cannot be accurately determined. Although it was a non-probability sampling method, it enabled the selection of people that matched characteristics determined by researchers for inclusion in the sample due to their availability at a given time or willingness to participate in the study. Invitation emails to ask teachers to fill in the online questionnaire were sent to both the education authorities and the principals of all the schools involved in the study.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic variables of respondents.

A link to the platform EUSurvey was sent to the schools to fill in the questionnaire. This is a secure tool recommended by the European Commission that guarantees respondents’ privacy and anonymity, as it is not possible to intercept the IP number and memorise the users’ cookies. All laws at the national and European levels and the General Data Protection Regulation n. 2016/679 (GDPR) were followed. The participants were provided with informed consent information about the data collection and usage according to the (GDPR) EU regulation, the study’s purpose, the contact persons for asking any clarification, their voluntary participation, the potential for harm, anonymity, and confidentiality. The questionnaire was organised into four main macro-areas investigating information related to: (i) socio-demographic characteristics; (ii) experiences, obstacles, and challenges with online learning; (iii) social inclusion and involvement of students; (iv) recommended intervention policies and their priority to improve online learning.

A pilot test was carried out to verify the validity of the questionnaire and the comprehensibility of its content. The software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences—SPSS 2012—was used to analyse data.

4. The COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey

The study involved 558 teachers; 318 of them were teachers from primary schools and 240 were from middle schools. The respondents were nearly all females, with only a few males. The number of females was disproportionately higher compared with males, following the typical trend in Italian schools, in which 84% of teachers are females. The average age of respondents was high; 239 teachers were aged 50–59. (See Table 1).

Table 2 describes a code to explain in a clear way the statistics of the study included in the other tables.

Table 2.

Code to read tables’ results.

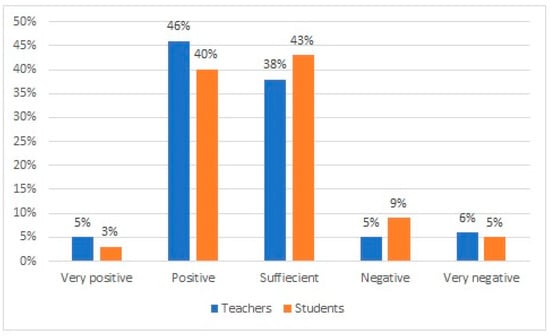

Although teachers faced numerous barriers and challenges to address during their time with online learning, overall, about half of them judged their experience as being positive. Online learning allowed them to avoid losing contact with their students, but it was not considered optimal for learning. Even so, 43% of them judged the experience of their students as sufficiently satisfying (See Figure 1). Teachers recognised some positive aspects of online learning such as the flexibility in providing learning, the possibility to record lessons, the removal of space–time barriers, and the possibility to personalise courses according to the student’s needs. However, the Italian school system is still facing several obstacles and must overcome many challenges. This experience allowed teachers to reflect on some lessons learned for more sustainable and high-quality education in the future. In the next sections, lessons learned by Italian teachers and the recent investments for the digital transition by policymakers to improve the quality of education will be discussed.

Figure 1.

Evaluation of online learning experience by teachers and students.

4.1. Lessons Learned about Online Teaching and Learning during the Pandemic

The experience with online learning during the pandemic emergency highlighted numerous criticalities of the school system, but at the same time allowed some lessons to be learned to face the future of education challenges.

The most important lessons learned by Italian teachers were the need to maintain or develop the infrastructure, improve digital skills through training, keep up to date on learning research and prepare for new developments, and being more flexible.

4.1.1. Need for Suitable and Reliable Technology

The pandemic has highlighted the importance of adequate infrastructure to support online learning, including access to reliable Internet connectivity, devices, and technical support. Schools have learned that investing in technology is essential to ensure that students can continue to learn in a remote or hybrid environment. Study results indicated, in fact, that the biggest barriers to online learning were related to the use of technology. Firstly, according to the teachers participating in the study, nearly all (93%) students did not have a stable Internet connection, 76% of them did not have access to hardware devices, and 82% of them shared devices with parents or siblings. This difficulty was greater for middle school students (85%), compared with 80% of primary school students. In some cases, children used smartphones to attend lessons, but the limited screen size caused some problems with the quality of learning [33]. The lack of adequate devices for learning was another problem both for primary school students (78%) and middle school students (74%).

4.1.2. Importance of Equity

The pandemic has exposed existing inequities in education, including disparities in access to technology and resources. Schools have learned the importance of addressing these inequities and of working to ensure that all students have access to high-quality education. Seventy-seven percent of teachers declared that their school implemented some interventions to encourage the involvement and inclusion of students with limited access to technology (networks and devices) or with low digital skills. Among interventions adopted by the schools, there were: the loan of devices; the supply of Internet connection; technical assistance; support for parents from teachers with tutorials, phone calls, messages on WhatsApp, etc.; and face-to-face lessons for students with special needs. The lack of inclusion interventions by schools can hinder students’ ability to access online learning resources, leading to further educational disparities.

4.1.3. Need for Training Courses

Online learning is different from traditional lessons in a classroom. The organisation of lessons online does not only consist of translating frontal lessons’ appearance for virtual use. Digital tools require appropriate training and support for teachers to ensure effective integration into teaching practice. At the beginning of the pandemic, Italian schools were unprepared to deal with online learning. In all, 28% of teachers felt completely unprepared to use online learning and 45% felt poorly prepared. Only 8% of teachers declared that before the pandemic they had any knowledge about apps/tools or platforms, and 21% felt they had insufficient knowledge before the pandemic. A significant challenge was, in fact, represented by the need for digital literacy and technical proficiency both for teachers and students. A total of 65% of respondents, in fact, did not receive any specific training, 21% received little, and only 17% received specific training in the use of online learning. After the lockdown experience, the situation has changed; then, in fact, 53% of teachers declared feeling quite prepared. There is still a need for specific and high-level training. Specific training courses for teachers both on platforms and new pedagogical methods are fundamental for the new digital environments.

4.1.4. Need for Easy-to-Use Digital Applications

Educational tools and platforms for education are sometimes not simple for children. In total, 47% of students had difficulty using tools for online learning and 42% of students did not receive any help from parents. This problem was greater for children in primary school (52%) that still need to be supported by an adult, compared with 29% of middle students that are more independent. Furthermore, technical assistance was also missing in many cases (38% of teachers). Therefore, it is fundamental to develop more inclusive, flexible, intuitive, and easy-to-use digital tools for children and students with special needs and guarantee technical assistance to support teachers.

4.1.5. Keep Students’ Attention and Engagement

It is difficult to maintain a high level of attention from children when staying in front of a computer for a long time. Teachers declared that 60% of students had reduced attention compared with lessons in a classroom. To address this challenge, some teachers during the pandemic successfully used an active form of teaching by stimulating students with continuous interactions during the pandemic. They learned that using multimedia resources such as games, quizzes, interactive videos, and competitions is very useful to motivate and engage students in interesting and stimulating learning activities. Educational games are designed to be fun and engaging, encouraging students to learn while having fun. More methods and tools for active and participative learning are needed by using interactive and emerging tools like virtual and augmented reality.

4.1.6. Greater Collaboration and Social Interaction

The shift to remote learning also highlighted the importance of social interaction and collaboration, as students and teachers needed to work together in new ways. According to the teachers, 52% of students had difficulties due to the lack of interaction and collaboration with classmates. In particular, 57% of middle school students had these difficulties compared with 49% of primary school students. Teachers learned to give a greater emphasis on developing these skills in students through group projects, cooperative learning activities, discussions, and other collaborative activities. Several difficulties were related to the students’ age. Since the interpersonal relationship was missing, the online modality was even more difficult, especially for the first classes of primary schools, and especially when the support of family was missing. Moreover, the absence of face-to-face interaction can negatively impact students’ social and emotional development. This situation led some teenagers to feelings of isolation and disengagement.

4.1.7. Prioritising Student Well-Being

The pandemic sometimes produced a significant impact on students’ mental health and well-being; therefore, educators are increasingly recognising the importance of social and emotional learning (SEL) in helping students to cope with stress and anxiety. Some teachers tried to maintain a dialogue with their students, mainly paying attention to their moods. Schools started to understand the importance of providing resources and emotional support to students, promoting a sense of community among students. This may lead to a greater emphasis on SEL skills such as empathy, self-awareness, and relationship-building in the classroom (also virtually).

4.1.8. Greater Emphasis on Flexibility and Personalised Learning

The pandemic also highlighted the importance of flexibility in education, as students and teachers frequently needed to adapt their behaviour and learning methods to different circumstances and schedules. As a result, many educators are exploring new ways to personalise learning experiences and offer more flexibility in assignments and assessments. Furthermore, teachers learned that flexible and innovative approaches and tools for students’ assessment are needed. The development of emerging technology and its spreading can answer these challenges. Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic has presented significant challenges to schools around the world. However, it has also stimulated changes and evolution in the learning landscape, pushing the educational system to start the adoption of new approaches to teaching and learning that will benefit students in the long term if integrated with those already used and consolidated.

4.2. Recommended Priority Intervention Policies

Starting from the lessons learned during the pandemic, teachers were asked to indicate priority areas for change and were given a list of some recommended intervention policies for the different stakeholders (policymakers, businesses, educational institutions, researchers, teachers, and students) to maximise the benefits of digital learning while minimising its barriers and addressing challenges in the near future. The questionnaire asked teachers to prioritise intervention policies to be implemented in the short, medium, or long term. Primary school and middle school teachers responded in a few different ways (Table 3a,b).

Table 3.

(a) Priority of intervention according to the number of primary school teachers. (b) Priority of intervention according to the number of middle school teachers.

The most requested intervention in the short term, as marked by half of primary and middle school teachers, was related to policies improving the network infrastructure, boosting Internet speed in all Italian geographical areas, and wiring all schools to offer good connection. Another intervention, requested with maximum priority by about half of primary and middle school teachers, was to ensure that all students have access to the necessary tools and infrastructure to participate in digital learning activities. Nearly half (43%) of primary school teachers and one-third (35%) of middle school teachers suggested addressing intervention policies to make devices cheaper, and about half of primary school teachers and some middle school teachers suggested having some government incentives to buy devices. High priority was instead given by most of the teachers to interventions related to providing teachers and students with ongoing support and training to improve their digital skills and facilitate student learning. Some primary school teachers (38%) gave maximum priority to the teachers’ training, while 36% of middle school teachers gave it high priority. High priority was given to the students’ training both by some primary and middle school teachers, including policies at the pedagogical level. According to the teachers, educational practices and curricula should be reviewed and made more effective to meet the needs of online learning. Some teachers suggested developing new teaching methodologies with the revision of the curricula. Furthermore, they also suggested developing new assessment methods, which were given high priority by one-third (34%) of primary school teachers and medium priority assigned by one-third of middle school teachers (31%). Other suggested interventions that teachers assigned high priority were related to technical aspects. Firstly, the development of more inclusive tools was needed, also for students with special needs, according to the international accessibility guidelines. Second, the development of more interactive platforms for students’ engagement, social interaction, and collaboration was requested by some primary and middle school teachers.

Finally, the intervention policies recommended which were given medium priority in the medium term were related to the development of emerging technologies. Teachers are starting to appreciate the integration of these technologies into education practices. The development of artificial intelligence to enhance personalised and inclusive approaches was, in fact, requested by some primary and middle school teachers. The development of virtual and augmented reality to make them more accessible to stimulate student involvement and interaction was a high priority for 34% of primary school teachers, while 28% of middle school teachers assigned a medium priority to this intervention instead.

Addressing the use of technology changes requires a concerted effort from several stakeholders and that a key feature of the new system is that they provide flexibility for schools. The digital transition is underway, and the overall policy aim is to enhance the educational system in Italy.

5. Government Policies for Digital Transition in the Schools

The coronavirus emergency has made evident that Internet access is an essential requirement for all. During the lockdown period, the gaps between people equipped with the tools to communicate, work, and study, reacting effectively to the crisis, and those who lacked such resources, have emerged stronger than ever. To answer these challenges, Italy is implementing an Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) called Italia Domani [34]. This plan establishes some reforms and investments for sustainable and inclusive economic growth and the digitisation of the country. Some of these interventions are related to the most strategic aspects of education. From this perspective, with the PNRR school, the Ministry of Education launched Plan School 4.0 [35], which includes a series of reforms and investments with medium- and long-term objectives. The goal of the PNRR is the creation of a new education system which both guarantees the right to study and is based on technological innovation, also providing skills to face the challenges of the future and the interactivity of students and the school system. This will allow for the overcoming of all inequalities and contrast early school leaving, educational poverty, and territorial gaps. The scheme of the interventions includes six reforms and eleven plans of investment. The six reforms are related to the most strategic aspects of education: the reorganisation of the school system, the training of teachers, recruitment procedures, the guidance system, and the reorganisation of technical and professional institutes and higher technical institutes. The eleven plans of investment are related to investments in infrastructures and competencies. Investments in infrastructures concern the creation of new safe, inclusive, innovative, and highly sustainable school buildings and innovative and digital learning environments and tools. The aim of the PNRR plan is to modernise school spaces by equipping them with technology that is useful for digital teaching, creating connected and digital learning environments. Investments in competencies concern digital education, equal opportunities, and the reduction in territorial disparities, technical and vocational education, and the development of multilingual and technical-scientific competencies. Some interventions are aligned with those requested by teachers. In particular, the Ministerial Decree n. 161 of 14 June 2022 [36] intends to promote the digital transition of the school system with an allocation of EUR 2.1 billion. This plan aims to transform at least 100,000 primary and secondary school classrooms into adaptive and flexible, connected, and integrated innovative learning environments with the introduction of connected educational devices, the internal wiring of approximately 40,000 school buildings and related equipment, and the creation of laboratories for new digital professions. In addition, EUR 800 million have been allocated for the creation of a multidimensional and strategic continuous training system for teachers and school staff, with a training offer of over 20,000 courses for the training of school principals, teachers, school staff, and technical and administrative staff and the adoption of a national framework for integrated digital education to promote the adoption of digital competence curricula in all schools. The objective is to promote digital teaching practices and training of school personnel on the digital transition, two key elements to improve learning quality and accelerate innovation in the education system. The plan, envisaged by the PNRR, aims to provide support to the actions that will be implemented by the educational institutions in compliance with their teaching, management, and organisational autonomy. These are the first positive and important steps towards the digitisation of schools, which will allow the country to have flexible learning environments and promote inclusion in line with the needs of children and young people. These interventions will allow some challenges and problems faced by teachers and students that emerged during the pandemic to be answered.

6. Potential and Perspective of the Metaverse in Education

The results of this study found that during the pandemic, teachers and students faced several challenges with online learning linked to infrastructure problems and also with didactical ones. They were mainly related to the lack of social interaction, engagement, and motivation of students. During the pandemic, synchronous platforms such as MS Teams, Zoom, Webex, Skype, etc., and asynchronous tools such as Moodle, Blackboard, social networks, etc., were used. These platforms are based on 2D web-based environments, which are less immersive and engaging if compared with traditional classroom teaching. The emerging Metaverse can mitigate these limitations by offering blended physical–digital environments.

The Metaverse integrates virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR), artificial intelligence, and cloud computing, making learning more attractive by giving users more immersive, interactive, and customised ways to learn [37]. The metaverse provides an immersive experience through digital interactivity, enabling people or their avatars to interact with each other and digital objects in a shared environment [38]. This technology, in fact, allows students to attend classes virtually, similarly to their real classroom. Students and teachers, in fact, can interact using their avatars. The Metaverse has the potential to deeply change the way education is delivered, making virtual learning more engaging, immersive, and interactive, and making virtual learning more usable for complementing the in-person lessons. The Metaverse has been criticised for being too vague and lacking a specific technology focus, but it is increasingly being discussed for its potential impact on the management of education [39]. One of the main benefits of using the Metaverse in education consists of offering the possibility to create more immersive learning experiences. Moreover, students can explore and interact with digital objects in a way that sometimes is not possible in traditional classrooms [40]. This can help students better understand complex concepts and develop new skills. Studies have shown that immersive environments can increase student engagement and motivation and, thus, improve learning outcomes [41]. In addition, the Metaverse allows for collaborative learning, where students can work together on projects and learn from each other in real-time [42] and develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills [43]. Another benefit of using the Metaverse in education is that it provides access to resources and experts that may not be available in a traditional classroom setting. For example, students can attend virtual lectures given by experts from around the world and access educational content that may not be available in their local area [44]. Metaverse technology can also be used to create personalised learning experiences. This technology can be used to create customised learning environments that are tailored to the needs and preferences of individual learners [45]. This approach allows for a more personalised learning experience, where students can learn at their own pace and in a way that is most effective for them [39]. In addition, Metaverse technology can be used to promote inclusivity and accessibility in education. In fact, it allows for the creation of learning environments that are accessible to students with disabilities (such as hearing or visual impairments) or those who face barriers to traditional learning methods, promoting social inclusion [46]. The metaverse opens new trends and future perspectives to education; however, more studies are required to evaluate the applicability of the Metaverse to practice [47], to understand how it may change the way students and teachers interact in the classroom [48], and to change pedagogical methodologies accordingly.

7. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the adoption of digital teaching in Italy, highlighting the need for innovative approaches to teaching and learning. Looking beyond the COVID-19 emergency, and according to our study, the pandemic highlighted many critical issues in the Italian education system. From this experience, many lessons were learned, highlighting the importance of developing strategies to address these challenges.

The study identified several lessons learned by Italian teachers, including the importance of investing in technology infrastructure, addressing equity issues, providing training courses for teachers, developing user-friendly digital applications, promoting collaborative and personalised learning, and emphasising flexibility and personalised learning. Most of the results were congruent with the literature [3,4,5,8,9,11,16,29]. These lessons can guide policymakers, educators, and stakeholders in shaping a more inclusive and resilient education system. Teachers, in fact, provided recommendations for various stakeholders to improve digital learning in the future based on lessons learned during the pandemic.

Short-term priorities included improving network infrastructure and ensuring all students have access to the necessary digital tools.

High-term priority interventions focused on training teachers and students in digital skills, revising curricula, and implementing new teaching and assessment methods. Technical actions involved developing inclusive tools and interactive platforms.

Medium-term priorities included utilising emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and virtual/augmented reality to enhance personalised and inclusive learning experiences.

In the meantime, governments and educational institutions are recognising the need to invest in bridging the digital divide, ensuring equitable access to online education for all students. From this perspective, this paper discussed the government’s role in supporting the digital transition in Italian schools, with a focus on the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR). The plan includes investments and reforms aimed at improving education infrastructure, digital education, equal opportunities, and reducing territorial disparities. These interventions align with the needs expressed by teachers and aim to promote digital teaching practices and provide training for school personnel to enhance learning quality and innovation in the education system. Overall, these initiatives are positive steps towards digitising schools, creating flexible learning spaces, and addressing challenges faced by teachers and students during the pandemic.

Technology will likely continue to play a more prominent role in education, as educators recognised the benefits of incorporating digital tools and resources into their teaching. The teachers participating in the study are, in fact, in favour of a greater use in the future of IT tools and innovative and interactive teaching methods in the logic of integrated teaching. In their opinion, digital resources must be integrated into daily teaching to support traditional teaching with more engaging and interesting tools and activities for young people. Similar results were found for universities; lessons learned suggest: (i) to integrate the technology in instructional practices, incorporating into learning processes some successful practices introduced during online learning [27,30], and (ii) to invest in technology and in innovative teaching and learning practices [28].

For the future, teachers would like a school that is more inclusive, personalised and open to technology, based on good educational teaching practices, and able to offer students the possibility of being the protagonist of the personal learning process. Schools today should look for more inclusive and creative pedagogical and teaching strategies and tools to respond, concretely, to the challenge that the way of working and studying online is becoming an integral component of education. The evolution of immersive, emerging, and innovative technologies will modify the learning processes of the students and will tend to influence the teaching methodologies used, and it will be a great opportunity to grasp all their potential.

Working from this perspective, this research paper explored the potential of emerging technologies for education, highlighting the perspectives of immersive technologies like the Metaverse. These technologies offer new possibilities for interactive and engaging learning experiences, fostering student creativity and collaboration. The integration of technology into teaching and learning can improve access to education, enhance the learning experience, and promote student-centred learning. However, the effectiveness of technology depends on the quality of its implementation and the careful planning and design of online learning experiences [26].

In conclusion, the COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted the education system in Italy. While it exposed existing challenges, it also created opportunities for innovation and transformation. By addressing the challenges and harnessing the opportunities presented by the pandemic, we can succeed at moving towards a more inclusive, resilient, and digitally transformed education system in Italy. This will allow schools to work towards the fourth goal (Quality Education) of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) stated by UNESCO to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” [49].

By capitalising on lessons learned from the pandemic experience, together with government initiatives and the potential of emerging and immersive technologies, Italy can achieve a resilient and digitally transformed future in education.

Limitations and Future Works

This study contributes to the literature providing a picture of the challenges faced and lessons learned by Italian teachers in primary and middle schools during their experiences with online learning in the pandemic period. However, since it used a convenience sampling, although the sample is diversified, involving teachers in the main regions of Italy, it is not fully representative. In a future survey, we intend to extend this study with more teachers and students by using statistically representative samples. We aim to analyse how educational institutions are integrating emerging technology in their programs, comparing results across different countries. Furthermore, we intend to analyse factors determining teachers’ and students’ acceptance of emerging and immersive technology in education.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su151410747/s1, Questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, T.G., F.F. and P.G.; methodology, T.G., F.F. and P.G.; validation, T.G.; formal analysis, T.G.; investigation, T.G.; data curation, T.G., F.F. and P.G.; writing—original draft preparation, T.G., F.F. and P.G.; writing—review and editing, T.G., F.F. and P.G.; supervision, T.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This article has been produced collecting data following all the requirements according to GDPR. The survey did not collect any personal or sensitive data and it was not possible to obtain them. For this reason, this statement was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions according to the informed consent signed by the participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UNESCO. Education: From School Closure to Recovery. 2023. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/covid-19/education-response (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- United Nations. Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond (August 2020). Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/08/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_august_2020.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Doyumğaç, İ.; Tanhan, A.; Kıymaz, M.S. Understanding the most important facilitators and barriers for online education during COVID-19 through online photovoice methodology. Int. J. High. Educ. 2021, 10, 166–190. [Google Scholar]

- Outhwaite, L. Inequalities in Resources in the Home Learning Environment; No. 2; Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunities; UCL Institute of Education: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Fordjour, C.; Koomson, C.K.; Hanson, D. The impact of COVID-19 on learning—The perspective of the Ghanaian student. Eur. J. Educ. Stud. 2020, 7, 88–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri, F.; Grifoni, P.; Guzzo, T. Online Learning and Emergency Remote Teaching: Opportunities and Challenges in Emergency Situations. Societies 2020, 10, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo, T.; Boffo, S.; Ferri, F.; Gagliardi, F.; Grifoni, P. Towards quality digital learning: Lessons learned during COVID-19 and recommended actions—The teachers’ perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8438. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, B.N. Are we prepared enough? A case study of challenges in online learning in a private higher learning institution during the COVID-19 outbreaks. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2020, 7, 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar, K.; Javed, K.; Arooj, M.; Sethi, A. Advantages, limitations and recommendations for online learning during COVID-19 pandemic era. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, S27–S31. [Google Scholar]

- Verawardina, U.; Asnur, L.; Lubis, A.L.; Hendriyani, Y.; Ramadhani, D.; Dewi, I.P.; Sriwahyuni, T. Reviewing online learning facing the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Talent Dev. Excell. 2020, 12, 385–392. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, F.; AlNasrallah, W.; Malik, M.I.; Rehman, S.U. Factors affecting the quality of online learning during COVID-19: Evidence from a developing economy. Front. Educ. 2022, 7, 847571. [Google Scholar]

- Basar, A.M. Problematika pembelajaran jarak jauh pada masa pandemi COVID-19: (Studi Kasus di SMPIT Nurul Fajri–Cikarang Barat–Bekasi). Edunesia J. Ilm. Pendidik. 2021, 2, 208–218. [Google Scholar]

- Azzahra, S.; Maryanti, R.; Wulandary, V. Problems faced by elementary school students in the online learning process during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indones. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2022, 2, 245–256. [Google Scholar]

- Aristana, M.D.W.; Ardiana, D.P.Y. Gamification design for high school student with unstable internet connection during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1810, 012057. [Google Scholar]

- Rincon-Flores, E.G.; Mena, J.; López-Camacho, E. Gamification as a Teaching Method to Improve Performance and Motivation in Tertiary Education during COVID-19: A Research Study from Mexico. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo, T.; Caschera, M.C.; Ferri, F.; Grifoni, P. Analysis of the Digital Educational Scenario in Italian High Schools during the Pandemic: Challenges and Emerging Tools. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1426. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto-Escamez, F.A.; Roldán-Tapia, M.D. Gamification as online teaching strategy during COVID-19: A mini-review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 648552. [Google Scholar]

- Marrara, S.; Saija, R.; Wanderlingh, U.; Vasi, S. Minecraft: A means for the teaching and the disclosure of physics. Nuovo Cimento C 2021, 44, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, Y.; Min, E.; Yun, S. Mining Educational Implications of Minecraft. Comput. Sch. 2020, 37, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Barut Tugtekin, E.; Dursun, O.O. Effect of animated and interactive video variations on learners’ motivation in distance Education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 3247–3276. [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea, A.; Ferri, F.; Grifoni, P.; Guzzo, T. Digital eco-systems: The next generation of business services. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Management of Emergent Digital EcoSystems MEDES’13, Neumünster Abbey, Luxembourg, 29–31 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, M.S.; Rogers, C. Education, the science of learning, and the COVID-19 crisis. Prospects 2020, 49, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro-Rueda, M.; Luque-de la Rosa, A.; Sarasola Sánchez-Serrano, J.L.; Fernández-Cerero, J. Assessment in Higher Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10509. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, V.W.Y.; Lam, P.L.C.; Lo, J.T.S.; Lee, J.L.F.; Li, J.T.S. Rethinking online assessment from university students’ perspective in COVID-19 pandemic. Cogent Educ. 2022, 9, 2082079. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Ma, Z.; Wang, L.; Yang, A.; Liu, Q.; Kong, S.; Wang, H. A survey on big data-enabled innovative online education systems during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100295. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, C.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.; Trust, T.; Bond, A. The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Educ. Rev. 2020. Available online: https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Lobos, K.; Cobo-Rendón, R.; García-Álvarez, D.; Maldonado-Mahauad, J.; Bruna, C. Lessons learned from the educational experience during COVID-19 from the perspective of Latin American university students. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2341. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.; Evans, E.; Reed, A.; Karch, L.; Qualey, K.; Singh, L.; Wiersma, H. Online, hybrid, and face-to-face learning through the eyes of faculty, students, administrators, and instructional designers: Lessons learned and directions for the post-vaccine and post-pandemic/COVID-19 world. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2022, 50, 301–326. [Google Scholar]

- Munir, H. Reshaping Sustainable University Education in Post-Pandemic World: Lessons Learned from an Empirical Study. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 524. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chan, M.C.E.; Kang, Y. Post-pandemic reflections: Lessons from Chinese mathematics teachers about online mathematics instruction. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2021, 22, 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, T.; De La Rubia, M.A.; Hincz, K.P.; Comas-Lopez, M.; Subirats, L.; Fort, S.; Sacha, G.M. Influence of COVID-19 confinement on students’ performance in higher education. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239490. [Google Scholar]

- Jager, J.; Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H. More than just convenient: The scientific merits of homogeneous convenience samples. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2017, 82, 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea, A.; Ferri, F.; Fortunati De Luca, L.; Guzzo, T. Mobile devices to support advanced forms of e-learning. In Multimodal Human Computer Interaction and Pervasive Services; Grifoni, P., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2009; pp. 389–407. [Google Scholar]

- Futura. La Scuola per l’Italia di Domani. Available online: https://pnrr.istruzione.it/ (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Piano Scuola 4.0. Available online: https://pnrr.istruzione.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/PIANO_SCUOLA_4.0_VERSIONE_GRAFICA.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Decreto Ministeriale n. 161 del 14 Giugno 2022. Available online: https://www.miur.gov.it/-/decreto-ministeriale-n-161-del-14-giugno-2022 (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Wang, Y.; Lee, L.H.; Braud, T.; Hui, P. Re-shaping Post-COVID-19 teaching and learning: A blueprint of virtual-physical blended classrooms in the metaverse era. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 42nd International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems Workshops (ICDCSW), Bologna, Italy, 10 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D.; Malodia, S.; Dhir, A. The metaverse in the hospitality and tourism industry: An overview of current trends and future research directions. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2022, 31, 527–534. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D.; Karatay, N. Mixed Reality (MR) for generation Z in cultural heritage tourism towards metaverse. In Proceedings of the ENTER 2022 eTourism Conference, Tianjin, China, 11–14 January 2022; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.; Wan, S.; Gan, W.; Chen, J.; Chao, H.C. Metaverse in education: Vision, opportunities, and challenges. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.14951. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Wang, L.; Koszalka, T.A.; Wan, K. Effects of immersive virtual reality classrooms on students’ academic achievement, motivation and cognitive load in science lessons. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2022, 38, 1422–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, A.; Suseelan, B.; Mathew, J.; Sabarinath, P.; Arun, K. A Study on Metaverse in Education. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Computing Methodologies and Communication (ICCMC), Erode, India, 23–25 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kaddoura, S.; Al Husseiny, F. The rising trend of Metaverse in education: Challenges, opportunities, and ethical considerations. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2023, 9, e1252. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A.; Cherner, T.; McEwen, B. Metaverse teaching and learning: Navigating the virtual world of education. TechTrends 2022, 66, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Zosh, J.; Hadani, H.S.; Golinkoff, R.M.; Clark, K.; Donohue, C.; Wartella, E. A Whole New World: Education Meets the Metaverse. Policy Brief; Center for Universal Education at The Brookings Institution: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zallio, M.; Clarkson, P.J. Designing the metaverse: A study on inclusion, diversity, equity, accessibility and safety for digital immersive environments. Telemat. Inform. 2022, 75, 101909. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, D.T.K. What is the metaverse? Definitions, technologies and the community of inquiry. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2022, 38, 190–205. [Google Scholar]

- Um, T.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.; Koo, C.; Chung, N. Travel Incheon as a metaverse: Smart tourism cities development case in Korea. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2022, Proceedings of the ENTER 2022 eTourism Conference, Tianjin, China, 11–14 January 2022; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives. 2020. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 15 May 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).