Conditions on the Sustainable Housing of Foreign Workers: A Case Study of Gyeonggi Province, South Korea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Design and Data Analysis

3. A Review of Existing Laws and Regulations on Sustainable Housing

4. The Status of Foreign Workers’ Residential Facilities in Gyeonggi Province

4.1. Current Status of Foreign Workers’ Accommodations

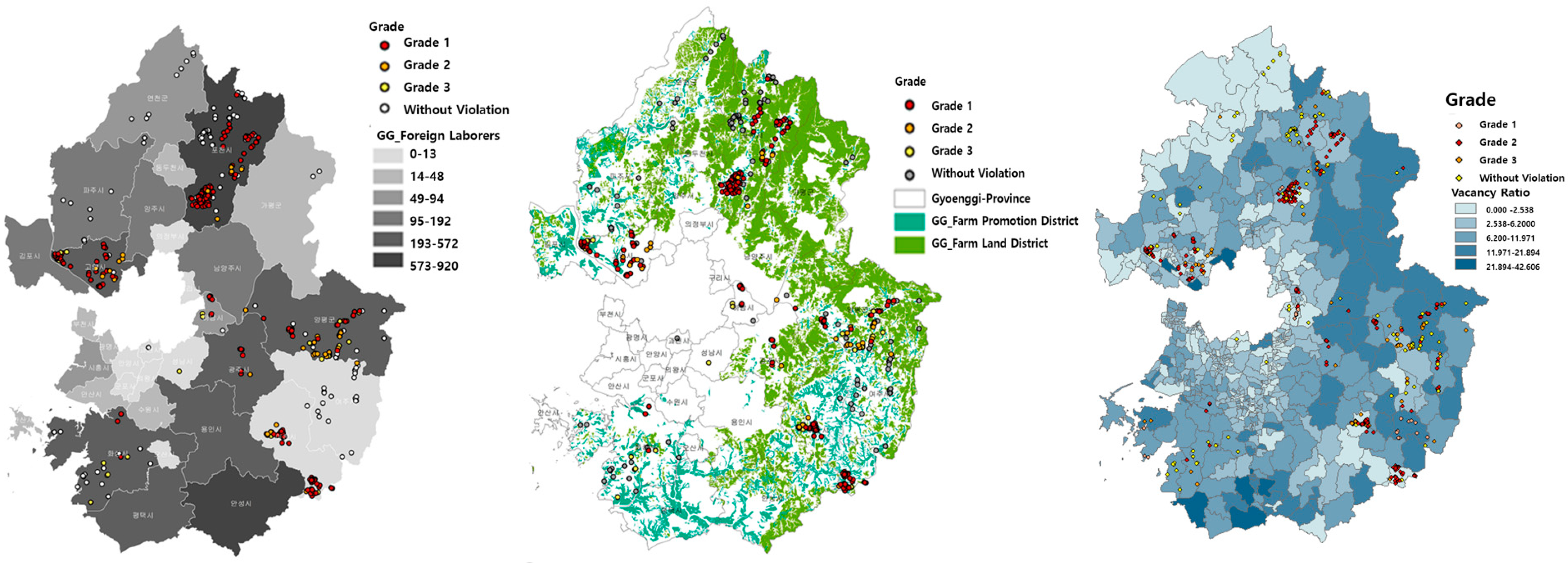

4.1.1. Location

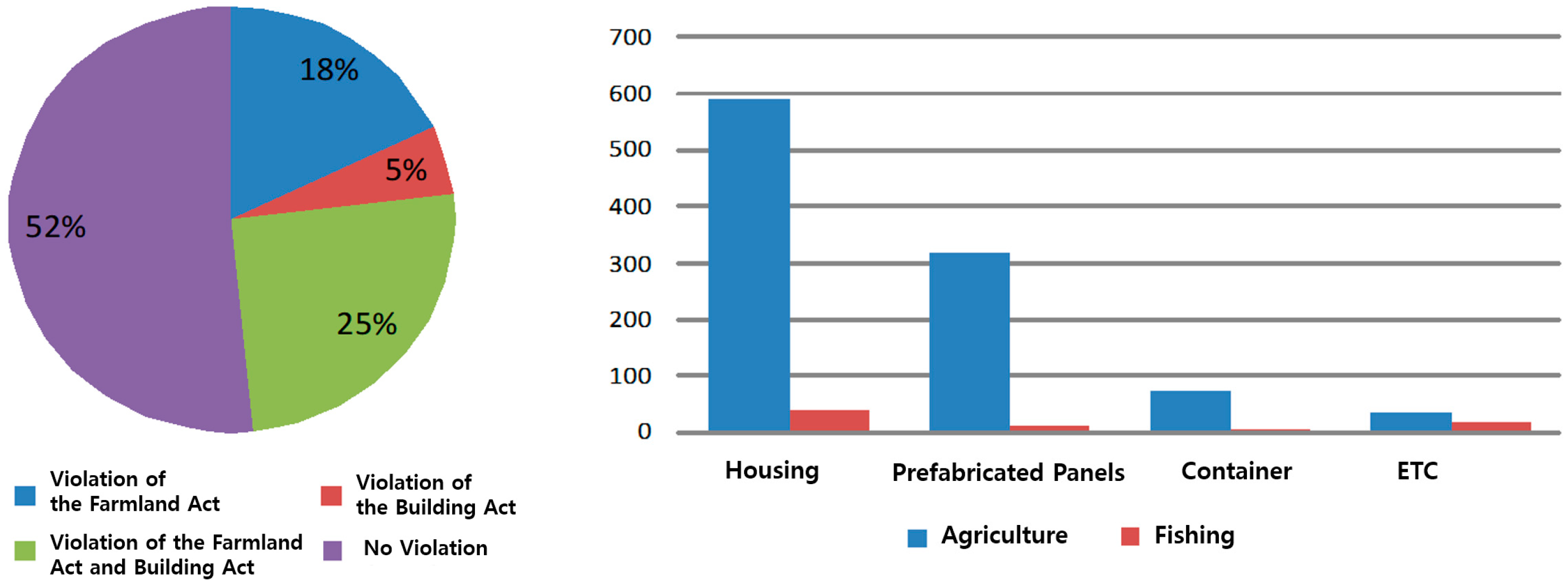

4.1.2. Building Structure and Facilities

4.1.3. Other Supplementary Facilities and Safety Issues

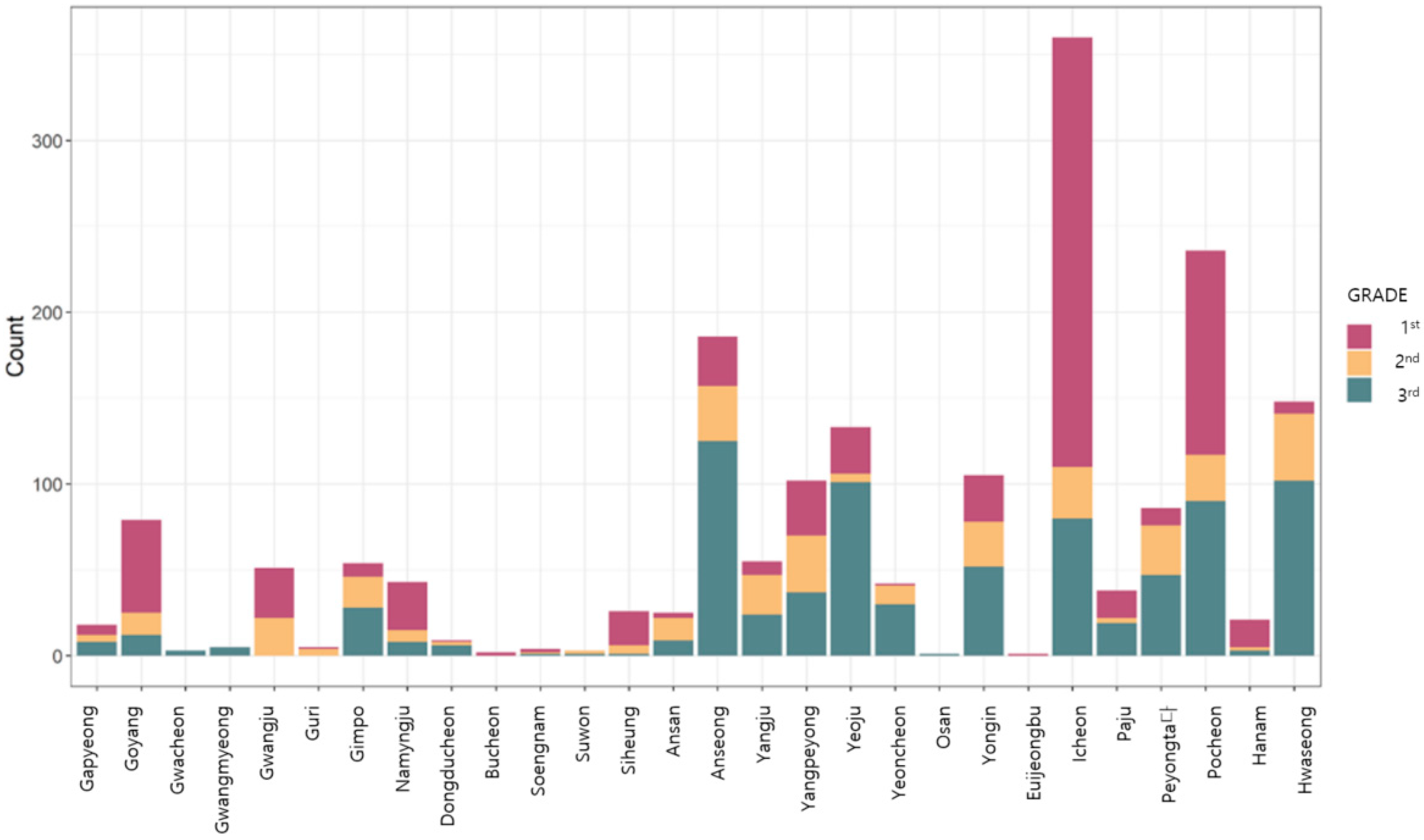

4.2. Analysis of Housing Vulnerability

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eom, J.Y.; Woo, B.J.; Kim, Y.J. Employment Status of Foreign Workers in Agriculture and Policy Tasks; Korea Rural Economic Institute: Naju-si, Republic of Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.O.; Song, J.A. Seasonal Needs of Migration Workers and its Supply: The Case Study of Cabbage Industry in Goesan, Korea. J. Korean Urban Geogr. Soc. 2016, 19, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.M.; Oh, K.S. A Study on the Support Plan for Foreign Workers in Gyeonggi-do; Gyeonggido Family & Women Research Institute: Suwon, Republic of Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, K.S.; Ko, H.M.; Lee, K.S. 2015 Survey on the Social Integration of Foreign Residents in Gyeonggi-do; Gyeonggi Instiute of Research and Policy Development for Migrants’ Human Rights: Suwon, Republic of Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Employment and Labor. Significantly Strengthening Standards for Acceptable Housing Facilities in the Farming and Fishing Sectors; Official press release; Ministry of Employment and Labor: Sejong-si, Republic of Korea, 2021.

- Gyeonggi-do Foreigner Policy Division. Residential Environment for Foreign Workers in-Farming and Fishing villages: Actual Condition Survey Results and Improvement Plan; Gyeonggi-do Foreigner Policy Division: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UN Habitat. Sustainable Housing for Sustainable Cities: A Policy Framework For Developing Countries, UN Human Settlements Program. 2012. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/8940535/Sustainable_Housing_Policy_Framwork (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Rauf, M.A.; Weber, O. Housing Sustainability: The Effects of Speculation and Property Taxes on House Prices within and beyond the Jurisdiction. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.J. A study on Improving the Supporting System for Foreign Workers in Local Government. Korea Local Adm. Rev. 2011, 25, 103–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.W.; Shin, K.H.; Lee, Y.J. The Real Condition of Labour in Seoul Immigrant Workers and The Protection Method for Labour Rights; The Seoul Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mohit, M.A.; Nazyddah, N. Social housing programme of Selangor Zakat Board of Malaysia and housing satisfaction. J. Hous. Built. Environ. 2011, 26, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M. Sustainable urban life in skyscraper cities of the 21st century. In Sustain City VI Urban Regener Sustain 129:203–214; WIT Press: Billerica, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Karji, A.; Woldesenbet, A.; Khanzadi, M.; Tafazzoli, M. Assessment of social sustainability indicators in mass housing construction: A case study of Mehr housing project. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iman, A.I. Sustainable Housing Developement: Role and significance of satisfaction aspect. City Territ. Archit. 2020, 7, 21. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). Social Housing in the UNECE Region: Models, Trends and Challenges; United Nations Economic Commission for Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kathleen Scanlon; Melissa Fernandez Arrigoitia; Christine Whitehead, Social Housing in Europe, Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies, European Policy Analysis, 2015.

- Scanlon, K.; Arrigoitia, M.F.; Whitehead, C. Social housing in Europe. In European Policy Analysis (17); Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies, 2015; pp. 1–12. Available online: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/62938/ (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Bailey, R. Suitable Accommodation for Seasonal Worker Programs, Department of Pacific Affairs. 2018. Available online: https://dpa.bellschool.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/publications/attachments/2018-11/ib2018_24_bailey_final_rev.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Korean Legislation Research Institute. Labor Standards Act (1997–2021). Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=59932&lang=ENG (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Ommeren, J.; Rietrveld, P.; Nijkamp, P. Job Moving, Residential Moving, and Commuting: A Search Perspective. J. Urban Econ. 1999, 46, 230–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. Workers’ housing, ILO Helpdesk Factsheet No. 6. 2009. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/empent/Publications/WCMS_116344/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Korean Legislation Research Institute. Act on The Employment of Foreign Workers (2008–2022). Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=56372&lang=ENG (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Korean Legislation Research Institute. Farmland Act (1994–2022). Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=56470&lang=ENG (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Korean Legislation Research Institute. Building Act (1996–2022). Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=59597&lang=ENG (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Habitat. 11.1 Adequate Housing. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/11-1-adequate-housing (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- International Labour Organization, Workers’ Housing recommendation, No. 115, General Principles, Para. 2. 1961. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:R115 (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (UN CESCR). General Comment No. 4: The Right to Adequate Housing (Art. 11 (1) of the Covenant); E/1992/23; United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Geneva, Switzerland, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. Home Truths: Access to Adequate Housing for Migrant Workers in ASEAN Region. 2022. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_838972.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Lee, H.S.; Choi, C.R. Proposed Amendment of Laws and Regulations to Guarantee the Right of Residence of Migrant Workers in Agriculture. In Proceedings of the Symposium on the Protection of Residential Rights of Migrant Workers; 2017; pp. 23–46. Available online: https://kiss.kstudy.com/Detail/Ar?key=3464909 (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. General Recommendation XXX on Discrimination against Non-Citizens. 2004. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/publisher,CERD,GENERAL,45139e084,0.html (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Sweeney, J.L. Quality, Commodity Hierarchies, and Housing Markets. Econometrica 1974, 42, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agricultural Safety and Health Bureau. Introduction to Migrant Housing Inspections in North Carolina; Agricultural Safety and Health Bureau: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. Migration and the Right to Adequate Housing. 2010. Available online: https://daccess-ods.un.org/access.nsf/Get?OpenAgent&DS=A/65/261&Lang=E (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Choi, S.H.; Park, J.H. An Analysis of Employment Conditions of Foreign Workers and Its Relationships with Local Labour Market; Gyeonggi Research Institute: Suwon, Republic of Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). Guidance on Workers’ Accommodation: Processes and Standards, European Bank. 2007. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/604561468170043490/pdf/602530WP0worke10Box358316B01PUBLIC1.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- UNECE. Housing for Migrants and Refugees in the UNECE Regions, Geneva. 2021. Available online: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2021-02/Housing%20for%20Migrants_compressed_0.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Working Together for Local Integration of Migrants and Refugees, ParisD Publishi. 2018. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issuesmigration-health/working-together-for-local-integration-of-migrants-and-refugees_9789264085350-en#page5 (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Ponzo, I. Immigrant Integration Policies and Housing Policies: The Hidden Links’, Fieri Research Reports. 2010. Available online: http://fieri.it/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Rapporto-social-housing-ethnicminorities_def_125013-16032011_ita.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Rapporteur: Mr Domagoj Hajdukovic, Croatia, SOC, Committee on Migration, Refugees and Displaced Persons, Integration of Migrants and Refugees: Benefits for all parties involved, Council of Europe, Draft resolution adopted by the Committee on 15 March 2023.

| Category of Conditions | Regulations and Policies |

|---|---|

| Category of conditions | 1. Labor Standards Act, Enforcement Decree of the Labor Standards Act

|

2. The Act on the Employment of Foreign Workers

| |

3. Farmland Act, Enforcement Rules of the Farmland Act

| |

4. Building Act

| |

5. Measures for Improving the Management of Farmlands

| |

| Building structure and facilities | 1. Labor Standards Act, Enforcement Decree of the Labor Standards Act

|

2. The Act on the Employment of Foreign Workers

| |

| Living conditions and environment | 1. Labor Standards Act, Enforcement Decree of the Labor Standards Act

|

2. Agricultural and Fishing Villages Improvement Act

| |

| Finances | 1. The Act on the Employment of Foreign Workers

|

2. Government projects for improving existing housing in agricultural and fishing villages

| |

3. Gyeonggi province’s bylaws on the operation and management of funds for improving rural housing

|

| Category | Regulations and Policies |

|---|---|

| Security of tenure | Housing is not adequate if its occupants do not have a degree of tenure security which guarantees legal protection against forced evictions, harassment, and other threats. |

| Availability of services, materials, facilities and infrastructure | Housing is not adequate if its occupants do not have safe drinking water, adequate sanitation, energy for cooking, heating, lighting, food storage or refuse disposal. |

| Affordability | Housing is not adequate if its cost threatens or compromises the occupants’enjoyment of other human rights. |

| Habitability | Housing is not adequate if it does not guarantee physical safety or provide adequate space, as well as protection against the cold, damp, heat, rain, wind, or other threats to health and structural hazards. |

| Accessibility | Housing is not adequate if the specific needs of disadvantaged and marginalized groups are not taken into account. |

| Location | Housing is not adequate if it is cut off from employment opportunities, health-care services, schools, childcare centers and other social facilities, or if located in polluted or dangerous areas. |

| Cultural adequacy | Housing is not adequate if it does not respect and take into account the expression of cultural identity. |

| Category | Regulations and Policies |

|---|---|

| Housing standards |

|

| Sanitation facilities |

|

| Classification | Classification Criteria |

|---|---|

| Grade 1 | Violation of housing type

|

| Grade 2 | Violation of supplementary facility requirements

|

| Grade 3 | Illegal accommodations that do not fall under Grade 1 or 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nam, J.; Gong, K.; Jo, H. Conditions on the Sustainable Housing of Foreign Workers: A Case Study of Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9095. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15119095

Nam J, Gong K, Jo H. Conditions on the Sustainable Housing of Foreign Workers: A Case Study of Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. Sustainability. 2023; 15(11):9095. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15119095

Chicago/Turabian StyleNam, Jeehyun, Keumrok Gong, and Heeeun Jo. 2023. "Conditions on the Sustainable Housing of Foreign Workers: A Case Study of Gyeonggi Province, South Korea" Sustainability 15, no. 11: 9095. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15119095

APA StyleNam, J., Gong, K., & Jo, H. (2023). Conditions on the Sustainable Housing of Foreign Workers: A Case Study of Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. Sustainability, 15(11), 9095. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15119095