1. Introduction

Due to the high dynamics and unpredictability of changes taking place in the modern economy and the constant increase in competition on the market, the ability to attract and retain experienced and talented employees plays a key role in obtaining a sustainable competitive advantage of the company.

The demographic decline, and thus the inevitable aging of societies in economically developed countries (EU, USA, Japan), and a significant improvement in the living conditions and health of citizens of these countries, with the simultaneous dynamic economic growth generating an oversupply of jobs, makes it necessary to extend the period of their professional activity. According to the data of the Central Statistical Office, in 2020 the percentage of people over 60 in Poland reached the level of 25.3%, while in 2050 these people will constitute about 40% of the total [

1]. A similar trend can be seen across the EU, where it is estimated that one-third of the population will be over 65 by 2060 [

2]. As a consequence, an increasing percentage of employees currently functioning on the labor market are representatives of the so-called “silver” generation, that is people over 50 years of age. These employees differ significantly from their younger colleagues (generation Y and Z), starting from their value system, approach to work, and professional career, to expectations towards work and the employer. It should be noted that the attitudes and expectations of employees towards work and professional career are constantly changing, evolving under the influence of various social, economic, and political factors, which implies the need to identify these factors and the relationships between them, as well as to determine their development tendencies.

This problem appears to be particularly relevant as the world enters the Industry 5.0 era and the consequent economic and social changes we are currently undergoing. The Industry 5.0 concept complements the existing Industry 4.0 approach, where through the development of innovative technologies, industrial processes, supply chains, and new business models, the transition to a sustainable, human-centered, and resilient industry is sought. Industry 5.0 provides a vision of over-engineered businesses that go beyond efficiency and productivity understood as primary goals. The concept places the worker at the center of the manufacturing process and leverages new technologies to deliver prosperity beyond jobs and growth while respecting the planet’s productive limits [

3].

All of this seems to be particularly important in the context of the unfavorable demographic changes currently being experienced by the societies of economically developed countries. This implies the need to identify the beliefs, needs, and expectations of workers over the age of 50, who will soon become the main driving force of the economy.

The results of this study will allow employers to more effectively activate employees of the “silver” generation (50+), and thus to fully use the potential of multigenerational teams. The result will be a more sustainable, optimal, effective, and innovative management of the human capital of enterprises in the era of Industry 5.0.

There are several definitions of the term “generation” in the literature on generational differences. For the first time, this term was described by Mannheim in 1928 in the work entitled

Das Problem der Generationen. According to the researcher, a “generation” is a cohort of people of similar age who experience common historical events. The inherent feature of this social construction is the common awareness of the experienced fate, similar attitudes and behaviors, goals, value systems, and principles of operation and interpretation of reality [

4]. A similar definition was repeated by Ryder in 1965, who described a “generation” in more detail as “a group of individuals who experienced the same event over the same time period” [

5]. Contemporary definitions of “generations” do not differ much from those quoted above. For example, Kupperschmidt defines a “generation” as “an identifiable group united by years of birth, age, location and significant life events in critical stages of development” [

6]. In summary, for the purposes of this study, a “generation” is defined as “a group of people roughly the same age who experience and are influenced by the same set of important historical events at key periods in their lives, usually in late childhood, adolescence and early adulthood”.

Based on the analysis of the literature on generational issues at work, five main groups of employees can be distinguished: “Silent Generation” (1922–1944), “Baby Boomers” (1945–1964), “Generation X” (1965–1980), “Generation Y”—so-called millennials (1980–1994), and “Generation Z” (born after 1994) [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. It is important to note that while most authors have adopted a common nomenclature and similar general timeframes to define particular groups, there is considerable discrepancy in the literature as to when exactly each generation begins and ends [

16].

In the light of demographic changes currently taking place on the labor market, employers are forced to manage the organization with particular emphasis on the generational diversity of employees [

17]. The problem of managing multigenerational teams is widely analyzed in the literature [

7,

12,

18,

19,

20,

21]. It is one of the most important parts of the issue of sustainable management of a company’s social [

22] and economic capital [

23,

24,

25]. Research on generations in the labor market usually focuses on distinguishing differences between individual generations [

15,

18,

21], as well as on defining a catalog of features characterizing employees currently functioning in the labor market [

8,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Currently, there are many companies employing three, and sometimes even four generations of employees, often with different preferences, values, and work styles. Therefore, it is very important in the context of proper management of such a team to thoroughly diagnose the characteristics of employees from particular groups [

30,

31]. At the same time, special attention should be paid to the skillful separation of characteristics resulting from generational affiliation from those resulting from other factors, such as organizational experience, seniority, and technological progress, which according to many scientists, is the main methodological challenge in generational research [

32,

33].

The impact of the systematic aging of the population is now an increasing problem for dynamically developing labor markets. Indeed, the age structure of the European population is expected to change significantly over the next decades. By 2060, the share of people over 65 years of age will increase from 18% to 30% compared to now, while the share of people over 80 years of age will be more than double. At the same time, the percentage share of the working age people (15–64 years) in the total population is expected to substantially decrease, from 67% to 57% [

34]. In Poland, also, tendencies to increase the number and share of elderly people in the total population can be observed. At the end of 2020, there were 14.4 million people aged 50 and over. They accounted for 37.6% of the total population and this share increased by 0.2% in relation to the previous year [

35]. It is estimated that in 2050 the percentage of people over 60 in Poland will reach 40% of the total population [

1]. Therefore, to maintain production and service capacities, companies are increasingly trying to encourage older workers to remain professionally active for longer. In order to achieve this, it is necessary to remove technological [

36] and social barriers that make it difficult to continue working and, most importantly, to learn about expectations and build an effective incentive system based on them, which will encourage professionally experienced people to postpone the decision to retire [

20,

34].

The need to prolong professional activity is also emphasized in the scientific literature, where the term “silver generation” was generally defined as a group of active people aged over 50–55 [

34,

37,

38,

39]. Taking into account the previously cited taxonomy of generational groups, people who are currently (2022) 50–55 years old were born after 1967, i.e., they belong to the so-called Generation X.

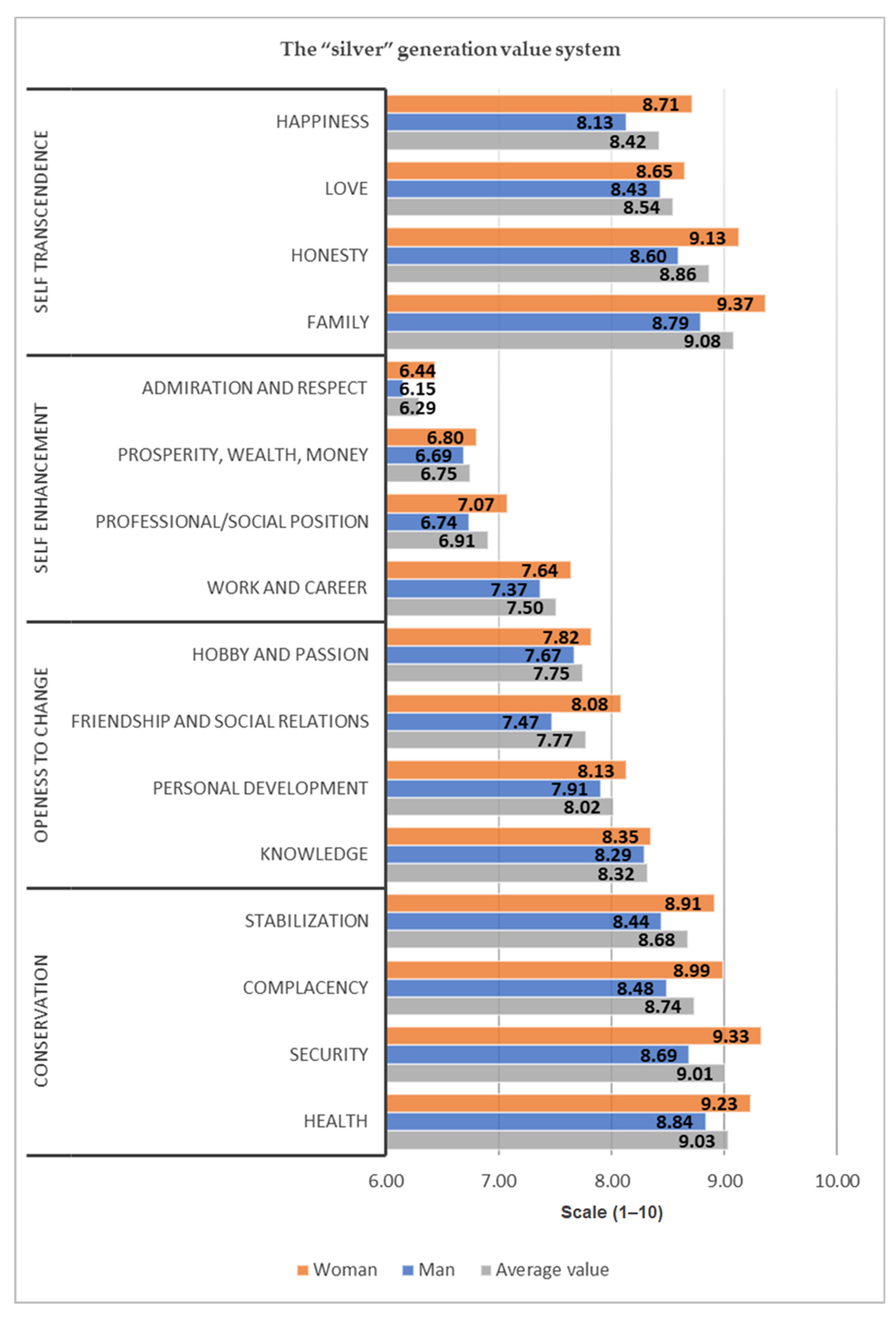

When reviewing the literature related to the topic of generations in the labor market, several basic groups of characteristics can be distinguished. Most often, generational cohorts are defined by the professed system of values, their attitude towards work, the level of professional satisfaction, and expectations regarding career development [

7,

9,

11,

14,

27,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Therefore, in the course of the research work, such a division of features characterizing employees of the “silver” generation was adopted.

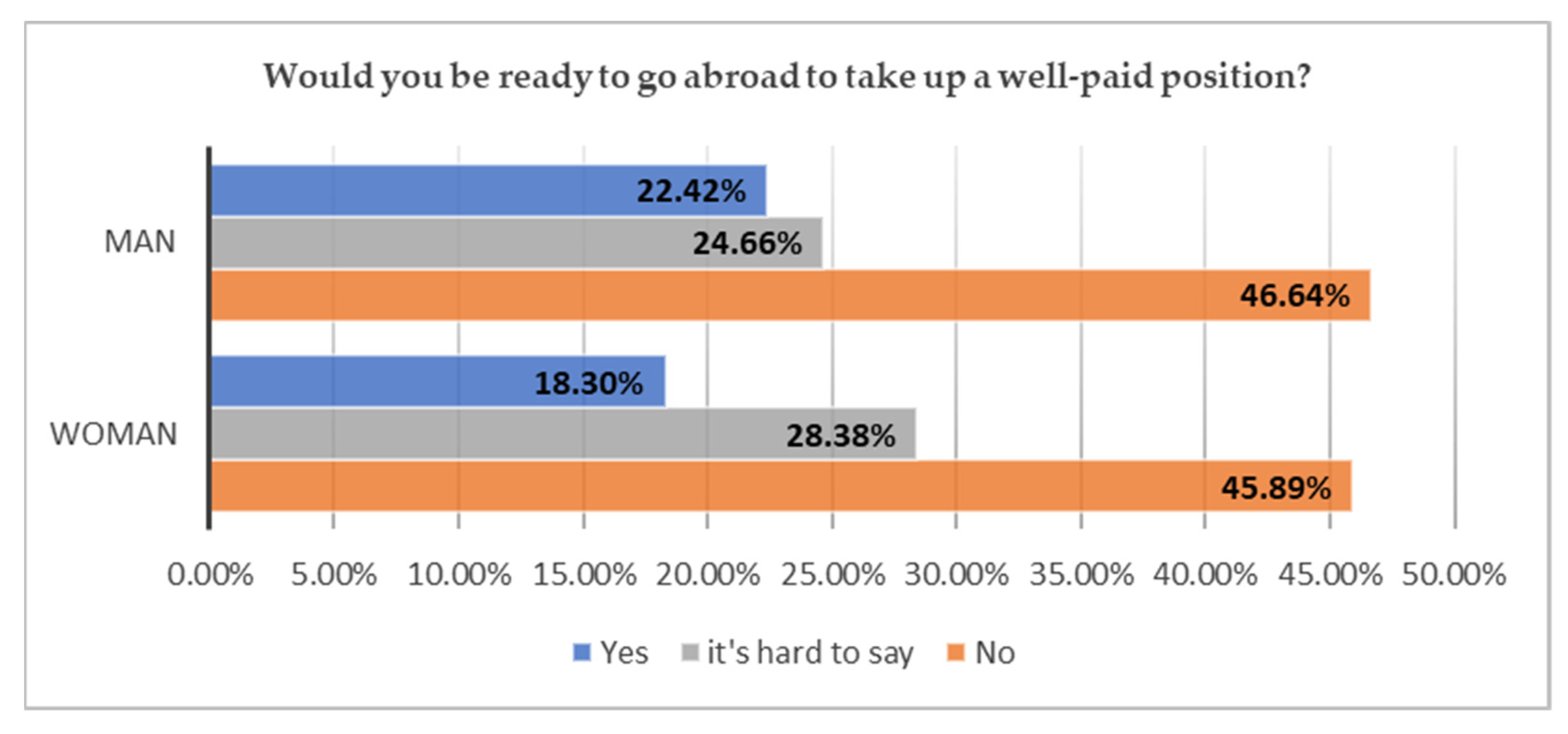

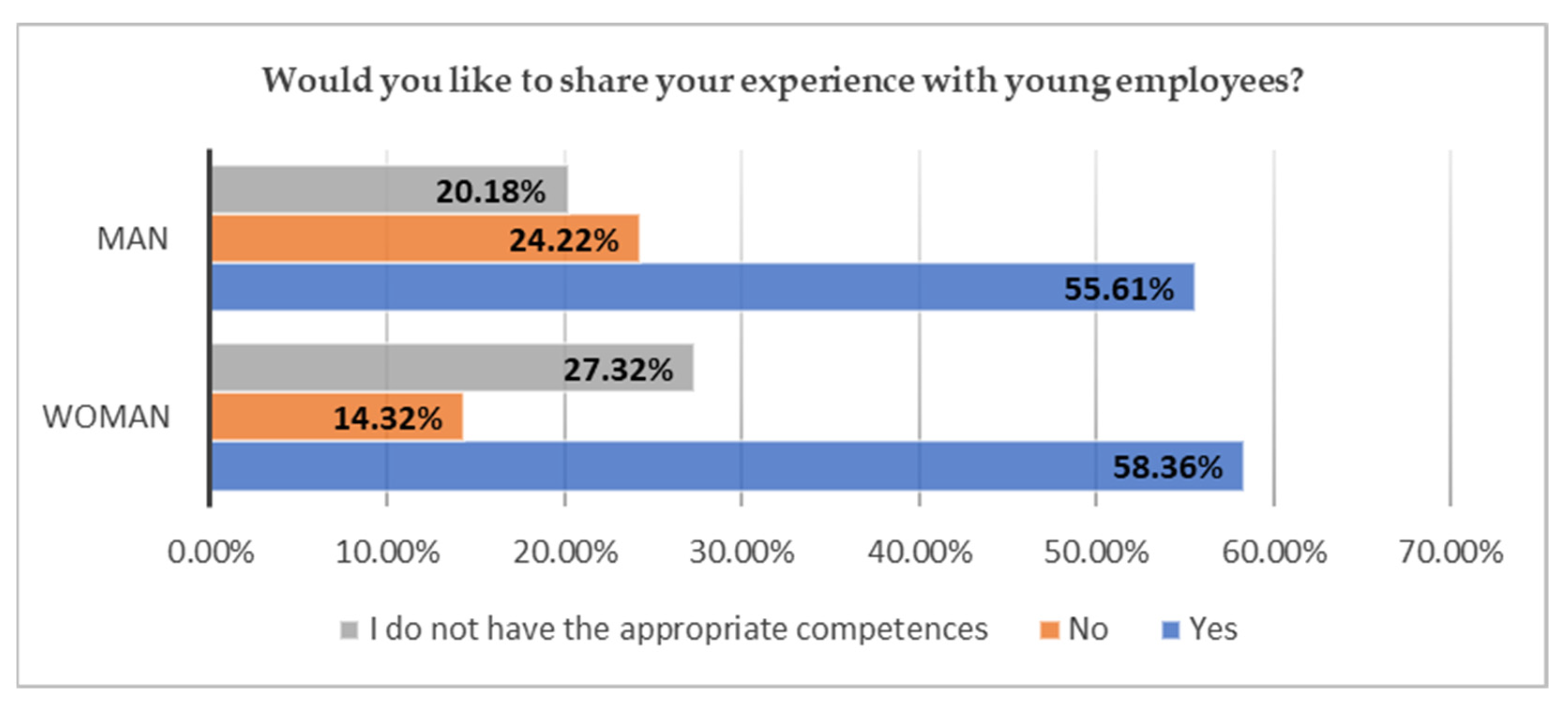

The main purpose of this work is to characterize the system of values, approach to work, and the related expectations of professionally active women and men over 50, and to determine whether, and if so, how the hierarchy of values, attitudes towards work, and job satisfaction affect the further development of their professional careers. The analysis of the literature on the subject, carried out at the initial stage of the investigation, allowed for the formulation of a general hypothesis (HG), which states that:

Characteristics such as the hierarchy of values, attitudes towards work, and professional satisfaction of both men and women employees of the “silver” generation have a significant, positive impact on the further development of their professional careers.

Each of us has values that are very important to us, perhaps completely irrelevant to someone else. Some of them are preferred and highly valued by humans, creating an individual hierarchy of values. The term “value”, “being valuable”, entered the vocabulary at the end of the 19th century. Currently, the

Oxford English

Dictionary defines the concept of “value” as “the regard that something is held to deserve; the importance, worth, or usefulness of something” or “principles or standards of behavior; one’s judgment of what is important in life” [

44]. In the literature, a number of theories characterize catalogs of human characteristics, which are also descriptors of his system of values [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. The common part of these works is the five-element characterization of values, which says that [

50]:

- (1)

Values are concepts or beliefs that are;

- (2)

Relate to the desired goals, describing the final states of affairs or behavior;

- (3)

Transcend specific situations;

- (4)

Guide the selection and evaluation of behaviors and events;

- (5)

Are ordered by importance.

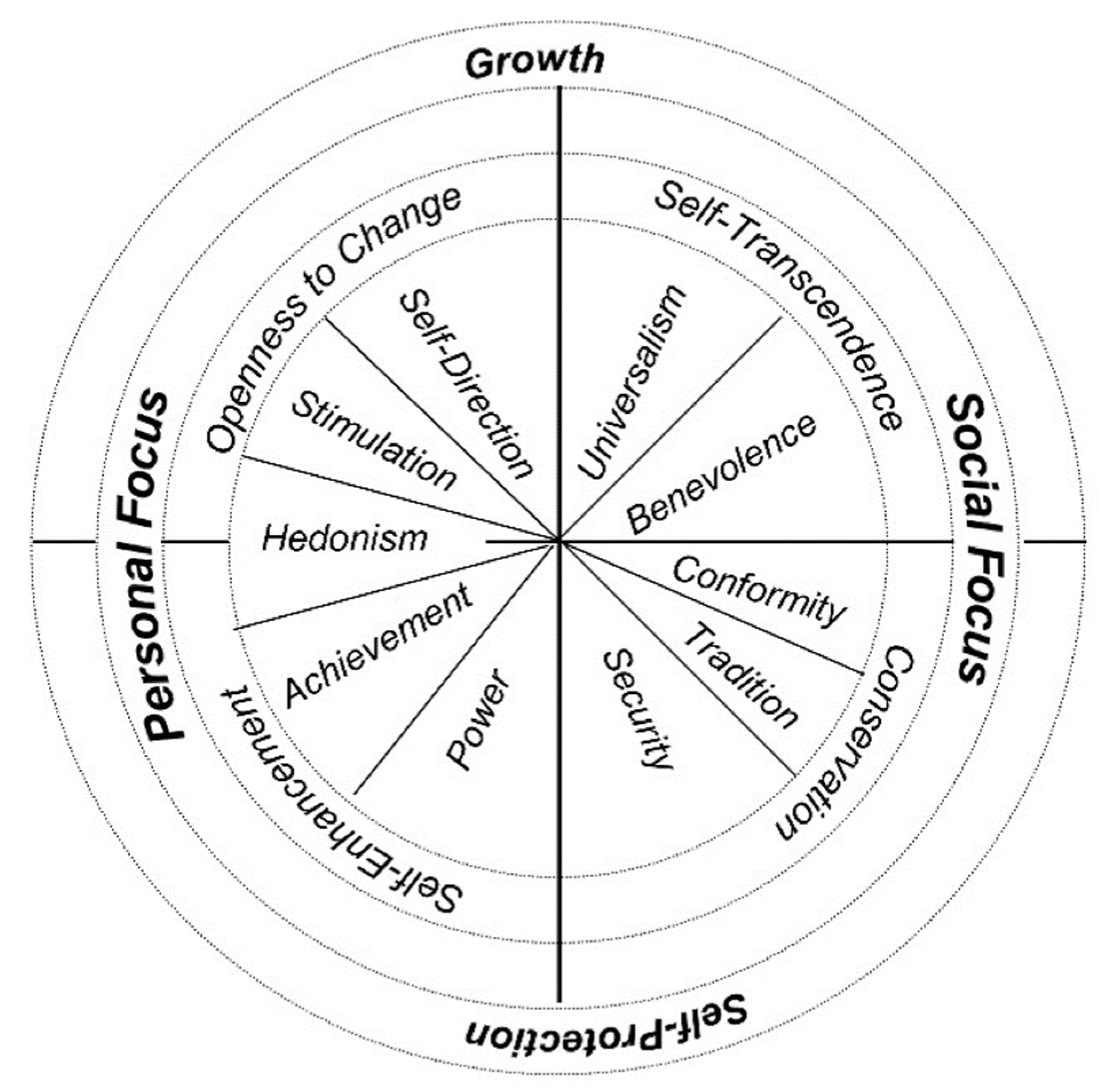

On the basis of these assumptions, the currently most popular theory of basic human values was created, the author of which is Shalom H. Schwartz. The main thesis of this theory is the assumption that the structure of human values is in the shape of a universal, motivational, circular continuum [

51,

52,

53]. In his studies, Schwartz also describes two rules ordering the values in the circle (

Figure 1), i.e., the rules of compatibility and conflict. The first of these rules states that values adjacent to each other in a circular model of values are possible to implement together because they are a cognitive representation of similar goals. On the other hand, the second rule assumes that values lying on opposite sides of the circle are not possible to realize together because they are cognitive representations of contradictory goals [

50].

The closer a value is to another value in the circle, the more similar are the motivations it expresses. Contrastingly, the more distant two values are, the more antagonistic they are in their motivations. Such an arrangement allows viewing values as organized along with a higher order of two bipolar dimensions: opposing self-transcendence (benevolence and universalism) to self-enhancement (power and achievement) values, and opposing conservation (security, conformity, and tradition) to openness to change (self-direction, stimulation, and hedonism) values [

54].

Previous research on values in human life proves that they are strictly dependent on the age of the respondent and change over time [

55]. People’s value systems differ depending on the country and cultural group they come from [

51,

56]. This diversity results from different historical and contextual circumstances, including different levels of political and economic development in the surveyed societies [

57]. Interestingly, there is also a very strong differentiation in the priorities of women’s and men’s values [

58].

According to these assumptions, a research hypothesis (H1) can be formulated, which says that there are significant differences between the value systems of women and men representing employees of the “silver” generation.

Generally speaking, the term “work” is defined as “activity involving mental or physical effort done in order to achieve a purpose or result” [

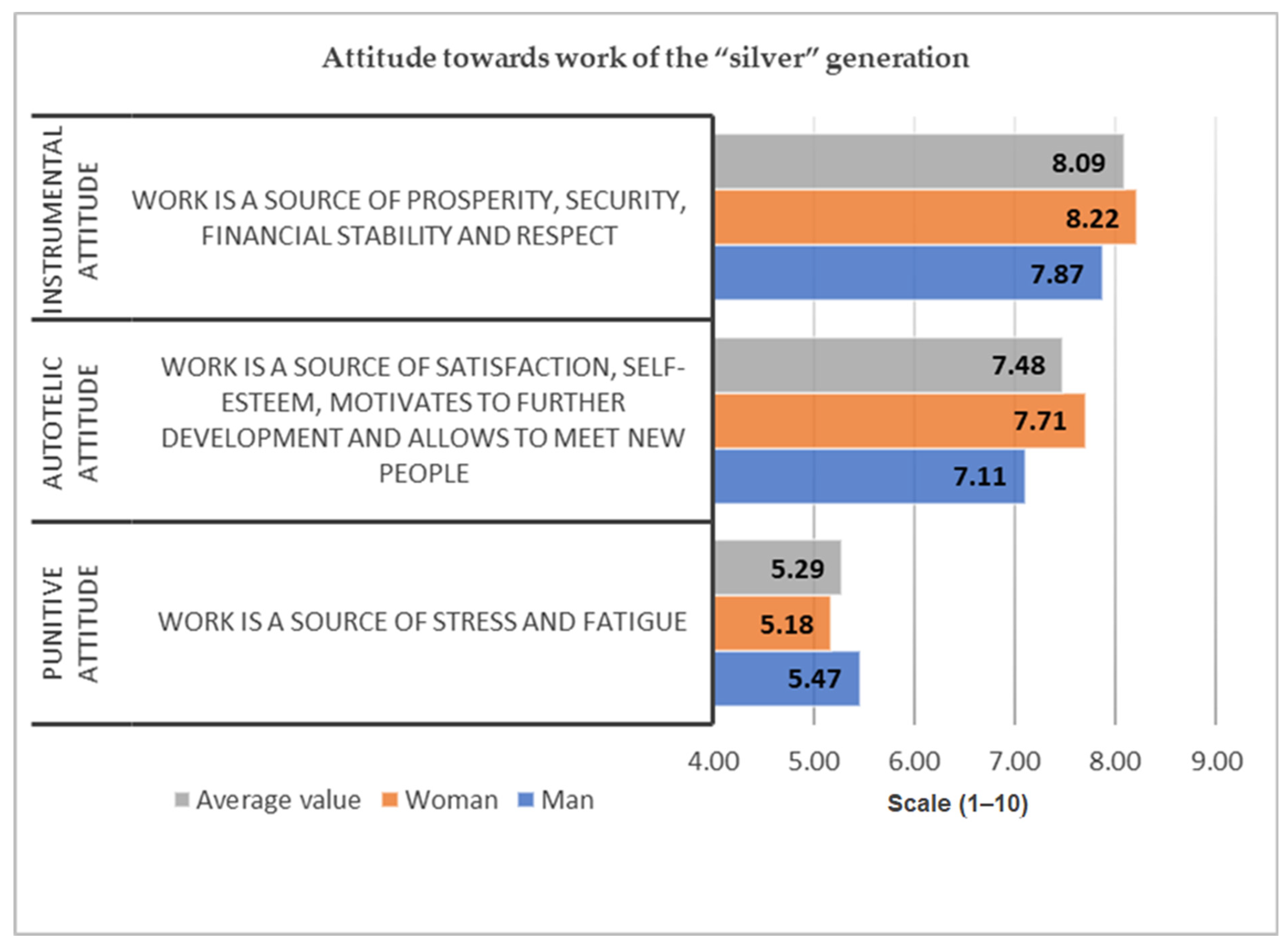

44]. In other words, it is any purposeful activity leading to the satisfaction of human needs that has social inclinations. Taking into account the values that work brings to an individual, three types of attitudes toward it can be distinguished: autotelic attitude, occurring when work is an end in itself and a way to meet the need for self-development; instrumental attitude, consisting of treating work as a means to the satisfaction of the basic needs of the employee, such as security and social contacts; and a punitive attitude, characterized by seeing work as a punishment, something unpleasant that must be avoided [

59]. To these attitudes, one can add a patriotic attitude, characterized by perceiving work as a service to society and fulfilling one’s duty to the homeland. It should be noted that contemporary studies of attitudes towards work do not focus on the attitude of a person to work as such, but consider the attitudes of an individual related to a specific, currently performed job. In this case, the following can be used as measures of attitudes towards work: the level of job satisfaction, commitment to work, and the sense of importance of work [

59,

60]. Research on people’s attitudes towards work shows that, as in the case of a value system, they depend on age and change over time. Since age is usually treated as a determinant of generational affiliation, it is commonly assumed that the attitudes towards work of representatives of different generations are different [

16,

40,

61,

62]. Furthermore, the conducted research also showed differences in attitudes towards work in terms of gender [

63,

64,

65].

Based on these assumptions, a research hypothesis (H2) can be formulated, which states that there are significant differences between the attitudes towards work of women and men representing employees of the “silver” generation.

Another very important descriptor of the “silver” generation employees is job satisfaction. One of the most frequently cited definitions of job satisfaction in the literature defines it as “a pleasant emotional state resulting from an individual’s perception of his or her job as realizing or giving an opportunity to realize significant values available at work, provided that these values are consistent with their needs” [

66]. Researchers dealing with the issue of job satisfaction point to its two basic aspects: emotional (affective) and cognitive [

67]. The affective factor consists of the employee’s feelings about work (short-term or permanent attitudes towards work), while the cognitive factor consists of what the employee thinks about the job (judgments about the work environment and tasks performed). This set is sometimes supplemented with a third factor, which is subjectivity in the perception of the situation resulting from individual characteristics (age, gender, nationality, and life experiences). The main factors determining job satisfaction are personal factors (needs, age, sex, and experience), organizational factors (type of work, remuneration, promotion opportunities, and working conditions), and social factors (organizational culture, ethics, relations with the supervisor, and cooperation in team) [

68]. The level of employee satisfaction can have a significant impact on customer satisfaction and loyalty [

69]. The most commonly used measures of job satisfaction are: remuneration, development opportunities, general evaluation of work, teamwork, organization and management, and working conditions [

70,

71,

72]. Research on the differences in professional satisfaction depending on gender proves that there are significant differences between men and women in this aspect [

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79]. Previous research also suggests that job satisfaction is not constant and changes over time. Some studies show a tendency to decrease job satisfaction in the 40–50 age group, with job satisfaction steadily increasing up to this point [

80].

According to these assumptions, a research hypothesis (H3) can be formulated, which states that:

There are significant differences between the level of professional satisfaction of women and men representing employees of the “silver” generation.

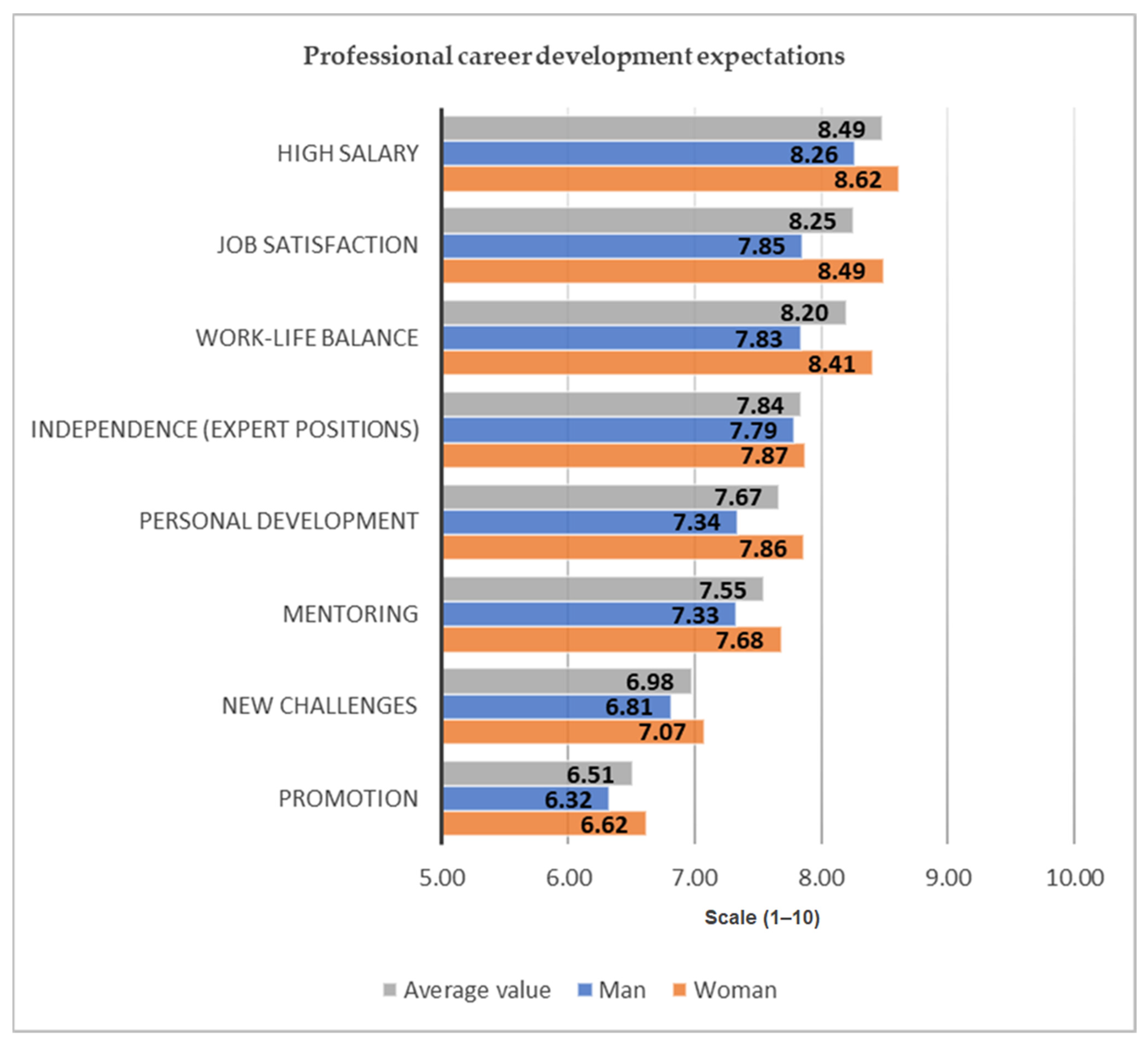

The concept of career development was first introduced to the literature in 1951 by Ginzberg, Ginsburg, Axelrad, and Herman. The basis for their considerations was the assumption that the choice of profession is a developmental process that lasts many years and ends in early adulthood [

81]. In the following years, Ginzberg clarified his position, assuming that it is a process of making professional decisions (professional choices) throughout life. This view is close to career development theorists [

82]. Brown and Brooks described career development as “the process of preparing for a choice, a process of choosing and constantly making choices from the many professions available in society” [

83]. Edgar Schein presented an interesting concept of career development. Assuming that there is a relationship between the values of a given person and the type of career chosen by him, he created the concept of “career anchors”, which are associated with directing a given person to one of eight possible values: professionalism, management (leadership), autonomy and independence, security and stability, creativity and entrepreneurship, idealism (meaning, truth, and dedication to others), challenges, and lifestyle [

84,

85]. In turn, John Holland in his research proved that people are looking for a work environment that will allow them to achieve self-realization, i.e., one that is consistent with their skills, personality, and preferences [

86]. Currently, we are seeing a gradual disappearance of the traditional linear career model, associated with stable working conditions and predictability of a professional career, towards a multidirectional, dynamic, and fluid career path. Examples of currently pursued careers can be protean career, borderless career, or kaleidoscope career. A protean career is associated with activity and a focus on development. A person pursuing such a career is guided by their own value system when making decisions and actions, is proactive and independent, and is focused on development [

87]. A borderless career is associated with mobility, moving from one company to another, and it may also concern the use of all opportunities to develop one’s competencies and professional potential in a given workplace. This career model can also be associated with the disappearance of boundaries between professional activity and other spheres of life. Such a career can involve crossing barriers related to physical mobility related to a change of industry or employer, and psychological mobility meaning readiness to change career [

88]. The concept of a kaleidoscopic career (ABC) emphasizes the fact that a person pursuing a career must face three key issues important for their development: authenticity, balance, and challenges. These areas form the “mirrors” of a kaleidoscope that can be related to the way of pursuing a career, giving unlimited possibilities to create different and unique career patterns. This model shows the perspective of pursuing different career paths, which depends on personal choices, activities undertaken, and the way of reacting to difficulties [

89].

The studies conducted so far on the differentiation of professional career development depending on gender prove that there are significant differences between men and women in this aspect [

90,

91,

92,

93]. According to these assumptions, a research hypothesis (H

4) can be formulated, which states that

There are significant differences between the expectations regarding the professional career development of women and men representing employees of the “silver” generation.

4. Conclusions

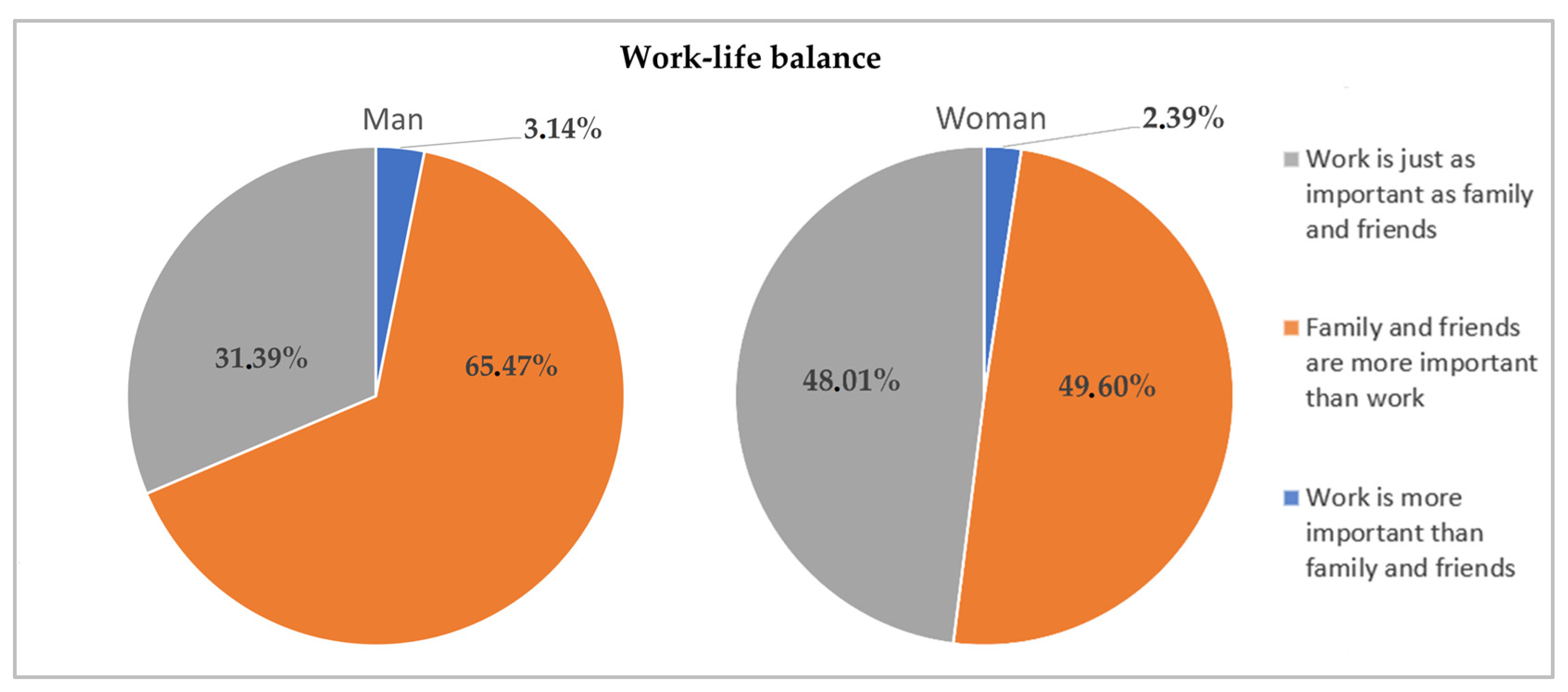

In summary of the above research, it should be stated that representatives of the “silver” generation are conservatives focused on family and private life, who value personal security, health, stabilization, and compliance. They consider universal values, such as family, honesty, and love and happiness, to be the most important in life, which they place much higher than career and professional position. Representatives of the “silver” generation are characterized by an instrumental attitude to work, which they treat mainly as a means to satisfy their basic needs, such as prosperity, security, financial stability, and respect. Undoubtedly, work occupies an important place in the lives of representatives of the “silver” generation; however, private life, that is, the opportunity to spend time with family and friends, seems to be more important to them. These people express their readiness to continue working after reaching retirement age, which is very good news from the point of view of the needs of the modern labor market. Factors that may motivate them to work longer include employment stability, financial security, the ability to maintain a balance between work and private life, as well as a low level of stress and a good atmosphere at work. Representatives of the “silver” generation identify their professional future with stability and security rather than dynamic development, manifested by a reluctance to change at work, such as long business trips. On the other hand, employees of the “silver” generation are ready to share their experiences with younger employees, which should be an impulse to build multigenerational teams.

In the course of the research work, it was confirmed that there are significant differences between male and female respondents in the evaluation of traits regarding their value hierarchy, attitudes toward work, and career prospects. Traits such as value hierarchy and attitudes toward work have a significant impact on the career development of both women and men of the “silver” generation, while professional satisfaction shows a significant (negative) impact on career development only for women.

In order to effectively utilize the potential inherent in the employees of the 50+ generation, it is necessary to implement innovative, customized solutions in the field of human capital management of the enterprise, such as, for example, implementing flexible forms of employment, maintaining partnership, inclusive and unbiased labor relations, and organizing work on the basis of multi-generational teams, formed for the purpose of performing a specific task. In addition, it is important to remember to treat modern technologies not only as a starting point and potential for increasing the efficiency of the enterprise but, above all, to apply a human-centered approach that puts basic human needs and interests at the center of the production process. In other words, instead of asking what can be done with new technology, ask what the technology can do for us. Instead of adapting workers’ skills to the needs of a rapidly evolving technology, use that technology to adapt the production process to the worker’s capabilities and needs.

It should be noted that these studies obviously have some limitations. The most important one seems to be the restriction of the research group to Polish citizens, whose peculiarities (history, social, and cultural characteristics) may in some way affect the results of the study. Therefore, it would be worth conducting similar research in other countries struggling with the problem of demographic decline (e.g., EU, USA, and Japan), which would allow for a more complete description of the “silver” generation at work. An interesting and needed direction for future research is also the issue of the functioning and management of multigenerational teams.