1. Introduction

The growth in the market for ecological products is related to striving for sustainable development, both in an economic as well as a social dimension. This significant megatrend is a response to the challenges of the modern world resulting from ongoing environmental degradation and the threat to the life and well-being of future generations. It is emphasised that ecology should be the principal common value at the end of the century [

1,

2]. Ecological awareness is increasing among consumers, who are ever more concerned by the scale of the threats resulting from ecological degradation. Consumers take more notice of the benefits they can obtain by changing their current behaviour and replacing conventional products with ecological products. This encourages firms and other organisations to apply eco-efficient practices, which are becoming accepted in many different sectors in order to achieve a competitive advantage, both in terms of price and cost. The promotion of consumer behaviours related to the purchase of environmentally friendly products is key to environmental sustainability [

3]. Incidents connected to food safety and environmental problems have attracted the attention of consumers worldwide to the quality and safety of food, as well as its environmental friendliness [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Demand for ecological products is strongly focused on North America and Europe (96% of sales), while in Asia, Latin America and Africa, ecological production is mainly intended for export [

9]. The United States has the largest market for organic food and drinks in the world, while in Europe, Germany and France are the leaders in this field, with Denmark, Austria and Switzerland having the biggest share of the organic food market.

In these countries, consequent action is being taken by all players in the food industry (farmers, processors, traders), as well as by consumers and politicians, that aim to strengthen ecological agriculture, above all by increasing the area taken up by ecological crops to 20%. This was achieved by Estonia and Sweden in 2019, with the figure reaching 26% in Austria. The indicator for Poland was at 3.5% of ecological crops, placing it fifth from the bottom (after Ireland, Malta, Bulgaria and Romania (Eurostat)). Poland is also a long way behind the highly developed countries of the European Union in terms of spending on ecological products. The highest spending per person is in Switzerland (EUR 418) and Denmark (EUR 384), with countries such as Luxembourg, Austria and Sweden above EUR 200, and Germany and France above EUR 180. There is also relatively high spending on such foodstuffs in the USA (EUR 148 and Canada (EUR 112) [

10,

11]. The average in the EU is EUR 76. Poland pales in comparison to such countries, with the average consumer spending around EUR 8 on organic food. There is, however, huge potential for growth in the ecological food market in Poland. This is due to the dynamic increase in spending in the segment, estimated at 20% per year, as well as the growing interest among consumers, the increasing availability of ecological products in supermarkets, and the development of specialist ecological shops.

The growing demand for ecological food has inspired the monitoring of consumer behaviours in order to examine the motives and reasons for such behaviours. The results depend above all on whether the research is conducted in mature ecological product markets or in developing organic markets, mainly in Asia. Meanwhile, cross-sectional research comparing mature and developing organic markets is scarce.

The significant differences in the development of ecological markets in individual regions and countries is the result of a wide range of factors that shape the level of socioeconomic development of these countries. These factors range from the existing civilisational gaps, which are expressed in the strategies and actions of companies, to the behaviours of consumers. The type and the intensity of influence of conditions for the development of ecological markets depend on the sector, the character of the products and their position in the hierarchy of consumer needs, as well as on lifestyles. The majority of studies examine the behaviour of firms in the ecological food market, but new trends in consumer behaviour reveal an ever-broader share in ecological markets of non-comestible products, such as biocosmetics and cleaning products, interior fixtures and fittings, clothes and electric cars. These are purchased by consumers who are more aware of the threats to life and well-being resulting from environmental pollution, climate change and the effect of epidemiological factors.

Consumer behaviour research with regard to ecological products in emerging market economies shows that an integral role in the shaping of attitudes towards ecological food is played by factors such as fears about food safety, awareness of the effect of ecological food on health, and susceptibility to media reports regarding foodstuffs. However, consumers’ concerns for the environment, as well as the taste of the food, are as yet of minimal significance in shaping and predicting their attitudes towards ecological food [

3].

Poland is among the countries that are striving to reduce the distance that divides them from the highly developed countries of Western Europe, North America and Australia. For this reason, it is a good setting for researching the process of growth in the ecological product market, with particular attention to consumer behaviour, as the expectations create challenges for the manufacturers and distributors of such products.

The aim of the article is to present the motives of Polish consumers behind their purchase of ecological products, and the factors that restrict the purchase of these products, as well as for which products they consider demand and consumption are likely to grow. As a result, the following research questions were formulated:

- Q1

Which motives dominate consumer behaviour in the ecological product market: egotistical or altruistic?

- Q2

What are the differences in motives for the choice of ecological products depending on consumer socio-demographic characteristics?

- Q3

Is there a dependency between consumers’ self-assessment of their level of knowledge about the functioning of the natural environment and the effect of humankind on it, and the purchase of ecological products?

- Q4

How do consumers perceive the factors restricting the purchase of ecological products?

- Q5

Is there a dependency between the reasons for restricting or excluding the purchase of products and consumers’ views regarding ecology?

- Q6

How do consumers perceive the opportunities of demand for ecological products growing?

The structure of the article includes the following parts: introduction, literature review, presentation of proprietary research methods, analysis of principal results, discussion and conclusion.

2. Literature Review

To explain the mechanism of consumer behaviour on the market for ecological products it is necessary to underline the dependency between attitudes, intentions to purchase and actual behaviour. Most importantly, there is a strong link between attitudes and the intention to purchase, but the link between intentions and actual consumer behaviour with regard to ecological products is weaker. This is due to the more powerful effect of external factors, mainly social, the expression of which are norms of behaviour as perceived by consumers [

12]. The influence of these factors means that consumer attitudes do not translate in the same degree into appropriate behaviour, i.e., purchases, especially of ecological food. Even a positive attitude towards ecological food does not necessarily lead to a purchase [

13,

14].

Numerous studies into the motives for purchasing ecological products have confirmed the role of the health aspect of ecological food, which is the most common reason for purchasing such food. Health as one of the principal motives for buying organic food is determined mainly by internal motives, including “feeling better”, preventing illness and self-image (e.g., attractive appearance), but also by external motives, i.e., social factors (e.g., peer pressure to eat healthily) [

15,

16]. The importance of health and safety as motives for the purchase of organic food has also been demonstrated by research conducted in Asian countries: China [

17], and Thailand [

18], as well as among Indian consumers [

19,

20].

Apart from health reasons, which remain the dominating motive for the purchase of ecological food and other ecological products, there is a growing importance of ethical motives, which should be reflected in marketing communication activities [

21]. The expression of such motives is ecological awareness, which plays a crucial role in shaping demand for ecological products. Its expression is not only the degree of emotional involvement in environmental issues but also an affective reaction to environmental protection [

22]. Consumers who have a high ecological awareness strive to improve the condition of the environment and are interested in purchasing products that are environmentally friendly [

17,

18,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25], as such purchases of organic food and other ecological products is considered to be pro-ecological and according to ethical principles [

26].

Numerous studies have shown that respondents are truly concerned by the state of the natural environment as it is currently under multiple threats such as pollution and global warming [

19].

Growing consumer ecological awareness has resulted in consumers trying to change their buying behaviour and displaying a greater tendency to purchase ecological products. Both ecological awareness and the level of knowledge about environmentally friendly products increase along with a rise in consumers’ level of education [

27]. For this reason, it is important to recognise the importance of ecological education, which shapes consumers’ ecological awareness and affects their behaviour on the market of ecological products. Researchers are striving to identify both the degree to which consumers reveal altruistic motivation, i.e., care for the natural environment, and their degree of egotistical motivation, such as the perceived better health benefits, nutritional properties and better taste of ecological products [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

Analysis of the literature indicates that two principal consumer segments dominate the ecological market, i.e., occasional consumers who purchase such food from time to time, and involved consumers, that is, regular buyers of ecological products. Empirical evidence indicates that occasional consumers constitute the principal segment in the market, with involved consumers making up the smaller segment [

28,

29,

30,

33,

34].

Occasional consumers are mainly driven by egotistical motives, i.e., care for their own health, and only partly by altruistic motives. Meanwhile, involved consumers who regularly purchase ecological products generally display altruistic motivation and are driven by ethical considerations as they are more aware of the beneficial effect of ecological products on the natural environment [

35,

36]. However, even in mature organic markets they remain a stable but smaller segment [

37]. Other research (e.g., [

38]) indicates that both regular and occasional consumers show great concern about the state of the environment.

In analysis of the factors shaping consumer behaviour on the market of ecological products, attention should be paid to the role of ecological certificates in shaping the attitudes and behaviours of consumers. This is because numerous studies have confirmed that knowledge about the environment and about ecolabels is significantly correlated with pro-ecological consumer behaviour [

39,

40,

41].

In emerging markets, a key barrier to behaviours relating to ecological food is the fact that the majority of consumers do not have sufficient knowledge about ecological products and do not know the basic differences between ecological and traditional food [

42]. Research conducted on the Polish market [

16] shows that consumers consider a lack of knowledge to be one of the reasons for not purchasing ecological food.

In countries with emerging economies, respondents are more likely to purchase ecological products made by home brands, although it is also underlined that information about the origin of the eco-certification does not have a significant influence on the intention to make a purchase [

43].

In highly developed countries, consumers demonstrate a greater knowledge about ecological products. For example, young Danish consumers consider themselves sufficiently competent in the field of ecology and demonstrate an ability to identify ecological products and evaluate them in comparison to non-ecological products in terms of quality and price. They also have a high level of trust in eco-labels [

44].

Additionally, in some Asian countries such as China, the majority of consumers are able to recognise ecological product symbols and recycling symbols. This concerns in particular young consumers, as they make use of technology and communication tools more often, and more frequently purchase ecological products [

27].

In addition, studies have shown that the greatest barrier to intentions to purchase organic food is the negative attitude of consumers towards ecological food [

14]. A lack of trust is also an important barrier to the development of the market for other ecological products.

Although ecological food products are considered to be healthy, the lack of trust in the origin of such products is the reason for consumers refraining from purchasing them [

45]. This is true for consumer behaviours in both countries with mature market economies such as Germany, as well as in emerging economies such as Chile [

46].

Research into the factors limiting the purchase of ecological products cannot ignore the price factor, which in many studies is considered to be the greatest barrier in the process of purchasing such products [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. However, other studies have shown that the cost borne by the consumer is not the greatest barrier to the desire to purchase ecological food, although it is seen as one of the key barriers [

14]. This is confirmed in the research results obtained by some authors, according to which it is not price but readiness to pay that is of key importance in the decision to purchase ecological products. Consumers must accept the higher price if they prefer ecological products to conventional ones [

52,

53].

It must be emphasised that the difference in the price of ecological food and conventional food is affected by the higher costs of producing organic food, market maturity, the relation between supply and demand, distribution channels and the degree to which the product is processed [

54]. Nevertheless, the average price of organic food products exceeds the difference threshold between ecological and conventional food acceptable for the majority of consumers [

55].

It has been demonstrated that the high prices and insufficient availability of ecological products are the main reason for the gap between attitudes and behaviour, especially among young consumers. This has been indicated by research in both mature market economies [

56] and in emerging economies [

57,

58]. Overcoming these barriers requires persuading consumers of the benefits generated by food and other ecological products in comparison to conventional products.

It is also worth underlining that a high price is a factor that limits to a greater degree repeat purchases of ecological food products than of conventional food products [

59].

Other research has shown that the level of consumer sensitivity to the high prices of ecological food depends on the quality of such food; if the food is of high quality and usefulness for clients, that is, it promotes health and safety, the sensitivity to higher prices is lower [

60].

The role of the price factor in shaping behaviour on the market for ecological products is evident in the reaction of consumers to price reductions on ecological food. This type of promotion more frequently prompts health-conscious consumers to switch from traditional purchases to the purchase of ecological products. At the same time, based on purchasing data for 36 product categories from the 2015 Nielsen Consumer Panel, the authors pointed to the varying price flexibility for both ecological and non-ecological food, irrespective of whether a product was purchased as part of a promotion or not [

61]. The importance of the price factor is also evident in the fact that consumers expect to pay extra for ecological products and indicate that such additional payments are relatively low [

56].

A further barrier to the increase in consumption of ecological products is the insufficient availability of such products. Availability is a large problem, as even though consumers are motivated, and the purchase, for example of ecological food, would actually be made, this becomes impossible due to the direct lack of availability of such products.

It must be emphasised that attitudes towards ecological products, evaluation of the characteristics of such products, and the willingness to pay higher prices for them all depend on socio-demographic factors. Available research indicates that factors such as gender, family income, education and professional status significantly differentiate between the attitudes and behaviour of consumers of ecological and non-ecological food [

2,

45,

62].

Young Polish consumers more frequently make their choices based on social and ethical issues, and have a positive attitude towards organic food, but they do not make regular purchases of this type of food. In their opinion, Polish products in the category of ecological food are less attractive than products from abroad. In addition, such consumers do not have enough knowledge on the labelling of ecological products, which would suggest that new forms of communicating these issues to young consumers should be sought, also in order to promote attitudes according to the concept of socially responsible consumption [

21].

Chryssohoidis and Krystallis [

63] claimed that the propensity to purchase green food is to a greater degree dependent on individual lifestyles than socio-demographic profiles. They confirm this in research which indicates that people who lead a lifestyle that includes a large proportion of physical activity attach greater importance to organic food, in which they have more trust [

64].

To understand the mechanisms of consumer behaviour on the ecological product market, in their analysis of the dependence between elements that shape consumer attitudes and behaviour, researchers include both the cognitive factor (i.e., knowledge about ecological products) and the affective factor (i.e., sensitivity and emotions) [

2,

39]. Integration of these factors in research is of key importance in understanding consumer behaviour and preparing effective green marketing messages.

Learning about the ever more complex expectations with regard to ecological products of various types of consumers, both young and old, of varying status and level of education, and leading different lifestyles, is a challenge for firms wishing to base their competitive advantage on offering such products.

3. Materials and Research Methods

The research process used in the article included the following stages: formulation of aims and research questions, selection of empirical research method, preparation of survey questionnaire, definition of criteria and selection of respondents for research sample, conducting empirical research, preparation of a report of the results, statistical analysis of the results, interpretation, and formulation of conclusions.

This article is based on the results of quantitative research conducted via an online research panel created and managed by the research institute ARC Rynek i Opinia in Warsaw. This body is an independent research institute with considerable experience and has been conducting market research since 1992. According to the Polish Association of Market and Opinion Researchers (Polskiego Towarzystwa Badaczy Rynku i Opinii—PTBRIO), which produces an annual ranking of research firms, ARC Rynek i Opinia is among the most recognised and valued research firms in Poland.

The ePanel managed by this firm has 75,000 registered users. To achieve the aims of the quantitative research study, the authors used a questionnaire that provided data on a representative sample of 1032 respondents from Poland.

The results of the research conducted with the use of the ePanel are representative of the Polish population aged 18–65 in terms of age, gender, region and size of place of residence. Due to the fact that in 2021, 92.4% of Polish households had access to the internet (GUS—Central Statistical Office data), the research was conducted using CAWI techniques so as to include a large group of respondents. However, the authors of the research are aware of the limitations of this type of research. Firstly, people without access to modern technologies could not participate in the research, which means that the sample does not meet the requirement of procedural representativeness. This drawback is common for internet samples, although the research agency took every effort to minimise this. Secondly, among the respondents drawn for the panel was an underrepresented group of people with the lowest level of education, and at the same time an overrepresentation of people with the highest level of education. Thirdly, the precisely defined age range registered in the participant panel favoured the participation of young people who are happy to use information technology and limited participation in the research in particular for older people. In the research sample, the youngest group—those frequently using new technologies—had a small overrepresentation, while the oldest group was slightly underrepresented. Fourthly, the declarativeness of answers of the research participants may not be reflected in their real actions. However, declarativeness affects all social science research including participants. Despite these critical observations, the authors consider the methodology used as optimal given the research aim.

The subject of analysis were the following dependent variables: motives for the selection of ecological products, the opportunities and limitations respondents saw to the growth in sales of ecological products, and the declared purchase (or not) of ecological products. The independent variables adopted were the demographic and socio-economic features of the respondents: gender, age, education, size of household, professional and economic situation, place of residence.

The structure of the sample is presented in

Table 1.

In total, 558 men and 474 women participated in the study. In terms of the age of respondents, the greatest proportion (44.4%) were people aged 25–44, while in second place were people aged 45–65 (42.5%). The smallest percentage (13.1%) were people aged 18–24. With regard to the number of persons per household, these were mainly 2-person (27.2%), 3-person (25.9%) and 4-person (22.8%) households.

The study participants had varying levels of education, including 45.5% of respondents with university education, 41.1% with secondary education and 13.3% with vocational and primary education. In terms of place of residence, respondents were obtained from all 16 voivodeships in Poland. Care was taken to ensure a suitable proportion of rural and urban populations. The percentage of respondents living in the countryside was 32.8%, and among the urban population, representatives from all types of towns and cities were included, with one in ten (14.1%) from towns up to 20,000 inhabitants, 22.8% in towns from 20,000 to 100,000 inhabitants, 29.7% in cities from 100,000 to 500,000 inhabitants, and 13.7% in cities above 500,000 inhabitants.

The research sample characteristics also included respondents’ professional situation. The majority of the respondents (61.7%) were employed on full-time contracts, while only 6.4% ran their own business or had a freelance profession. There were also relatively large proportions of retirees and benefit recipients (11.7%) and students (7.0%). In terms of respondents’ economic situation, half described it as average, one in four as good, and 6.6% as very good. Almost one in ten respondents (9.2%) assessed their income situation as bad or very bad.

In the statistical analysis of the respondent data obtained, statistical tools and techniques were used adequately to the measurement scale and response type (single or multiple answers).

The attachment (

Appendix A) includes the questions from the survey questionnaire that were the basis for this article. Question 4 was a multiple-response question, the remaining questions were multiple-choice. The answers to questions 1, 2, 4 and 5 were measured on a nominal scale, and the answers to questions 3, 6 and 7 on an ordinal scale.

In

Section 3, bibliographic references have been included referring to the statistical methods used.

When respondents provided multiple-choice answers to questions, measurements were made using a nominal scale. For individual questions, to verify the random distribution and layout of the answers, chi-square and entropy tests were used [

65] To verify the dependence between answers to questions on motives, factors, reasons for limitations and perceived opportunities, and respondents’ characteristics, as well as the dependence between the level of knowledge and purchase decisions, a chi-square test of independence and a test of proportion were used [

66]. This enabled the identification of significant differences between the categories studied. Due to the varying sizes of the contingency tables, assessment of the strength of dependence was conducted with the use of Pearson’s adjusted contingency coefficient. Meanwhile, single answers were measured on an ordinal scale. To determine the significance of reasons for limiting purchases as well as the opportunities for an increase in demand, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used, while the Spearman correlation rank coefficient (rho) was used to assess correlation dependence [

67]. The starting point for the verification methods described above was an analysis of the frequency of distribution of responses.

To identify the hidden factor structure for the likelihood of an increase in sales of ecological products, as well as the principal limitations to this increase, multidimensional comparative analysis was used, i.e., explorative factor analysis [

68,

69,

70]. The factor analysis was conducted separately for the opportunities and the limitations. Assessment of the importance of the factors (opportunities and limitations) was made by respondents on a 7-point scale (1—very low importance, 7—very high importance). The same assessment scale allowed respondents’ average assessments to be compared. The justification for using factor analysis in each case is indicated by: (i) very high Kaiser–Meier–Olsen statistical test values (a KMO significantly exceeding 0.7), proving the adequacy of the correlation matrix with regard to the assumptions of the factor analysis, and (ii) a statistically significant Bartlett sphericity test result (

p = 0.000), confirming that the correlation matrix as a whole contains significant correlation coefficients (

Table 2).

Explorative factor analysis was performed using the principal components method with Varimax rotation (with Kaiser normalisation). The Varimax rotation applied minimizes the number of variables used to explain a common factor. To determine the number of components and explain at least 70% of the common variation, a scree plot criterion was used. Three or four components were extracted. The common factors extracted together explain more than 75% of the variance of results, which should be considered a high degree. In the dimension reduction procedure, all factors were taken into account—both opportunities and limitations. It must be added here that in each case, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test confirmed the importance of the opportunities and limitations, and the average assessment of the importance was higher than 4.6. The reliability and high consistency of the scale made up of such a number of variables is confirmed in each case by a very high Cronbach’s alpha statistical value (greater than 0.9) (

Table 2). Meanwhile, after individual questions are removed, Cronbach’s alpha values are not higher than the statistics calculated for the initial number of variables together, which does not provide a basis for reducing the set of factors in the analysis.

4. Results

The starting point for research into factors shaping purchasing behaviour in the ecological product market references the motives for purchasing such products. The purchase motives indicated most frequently by respondents were: care for one’s own health (22.4% of all indications), care for the health of family and children (19.6%), and care for the environment (24.1%). Both men and women gave these three motives, wherein for women the most important was care for one’s own health (24.2% of indications by women), and for men—care for the environment (24.7% of indications by men). To examine the existence of dependencies between purchase motives and respondents’ characteristics, the chi-square independence test was used, and the Pearson adjusted contingency coefficient was calculated (

Table 3). Of statistical significance (α = 0.05) were found to be the dependencies between purchase motives and gender, age and size of a respondent’s household. The Pearson adjusted contingency coefficients indicate that in the majority of cases these are low but distinct dependencies. Very weak dependencies appear between purchase motives and gender, as well as between purchase motives and education.

Women indicated healthcare motives (their own and their family’s) more often than men, while men more frequently than women indicated being accustomed to such purchases. Respondents from each of the five age groups (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54 and 55–65) made their product purchase choices based on the three motives mentioned above: care for one’s own health, the health of the family, and care for the environment. What is more, care for the environment above all motivated such purchases in every age group. Statistically significant differences in the frequency of indications related to the motive of caring for the health of the family and children, with people aged 45–54 more frequently giving this reason than those aged 18–24. For the remaining characteristics of the respondents: size of locality of residence, education, professional situation, economic situation and size of household, the three purchase motives mentioned earlier remain unchanged. The principal motive is care for the environment in all categories in terms of education and economic situation, and in the majority of categories for the remaining three characteristics. Respondents from almost all sizes of city indicated this reason, but respondents from towns of 50,000–99,000 inhabitants most often declared care for the health of family and children, while for inhabitants of the countryside it was care for their own health. In terms of professional situation, those who run their own business and who work freelance most frequently focus on their own health when buying ecological products, while homemakers focused on care for the health of the family and children. Statistically significant differences in the frequency of indications in a couple of groups defining professional status related to the motive of care for the environment (retirees, benefit recipients, pupils and students more often gave this reason than those running their own business and freelance workers) and care for the health of the family (homemakers indicated this reason more often than pupils or students). The motive of care for the environment dominates among respondents in one-, two- and five-person households, while representatives of the remaining household sizes most often indicated care for their own health, for which the percentage increases along with the size of the household. Statistically significant differences in the frequency of indications related to the motive of care for the health of the family and children, with people from two- and four-person households giving this reason more often than those from one-person households. This indicates the higher sensitivity of people living in larger households resulting from their increased responsibility for the problems of members of these households.

To summarise the research results, a division of the motives was made into two groups: egotistical and altruistic. Egotistical motives were expressed in the following variables: care for one’s own health, care for the health of family and children, attention to one’s appearance, well-being, habits, fashion for buying ecological products, and pleasure resulting from being close to nature. Altruistic motives were expressed in the variables: care for the environment, the need to support local producers, and lowering unemployment. A clear majority of respondents (72.1%) who purchased ecological products indicated at least two egotistical motives, with every eleventh respondent (9.2%) indicating three egotistical motives. At least two altruistic motives were given by 21.4% of those purchasing ecological products, however, none of the respondents indicated three such motives. Meanwhile, 6.5% of purchasers of ecological products gave the same number of egotistical and altruistic motives.

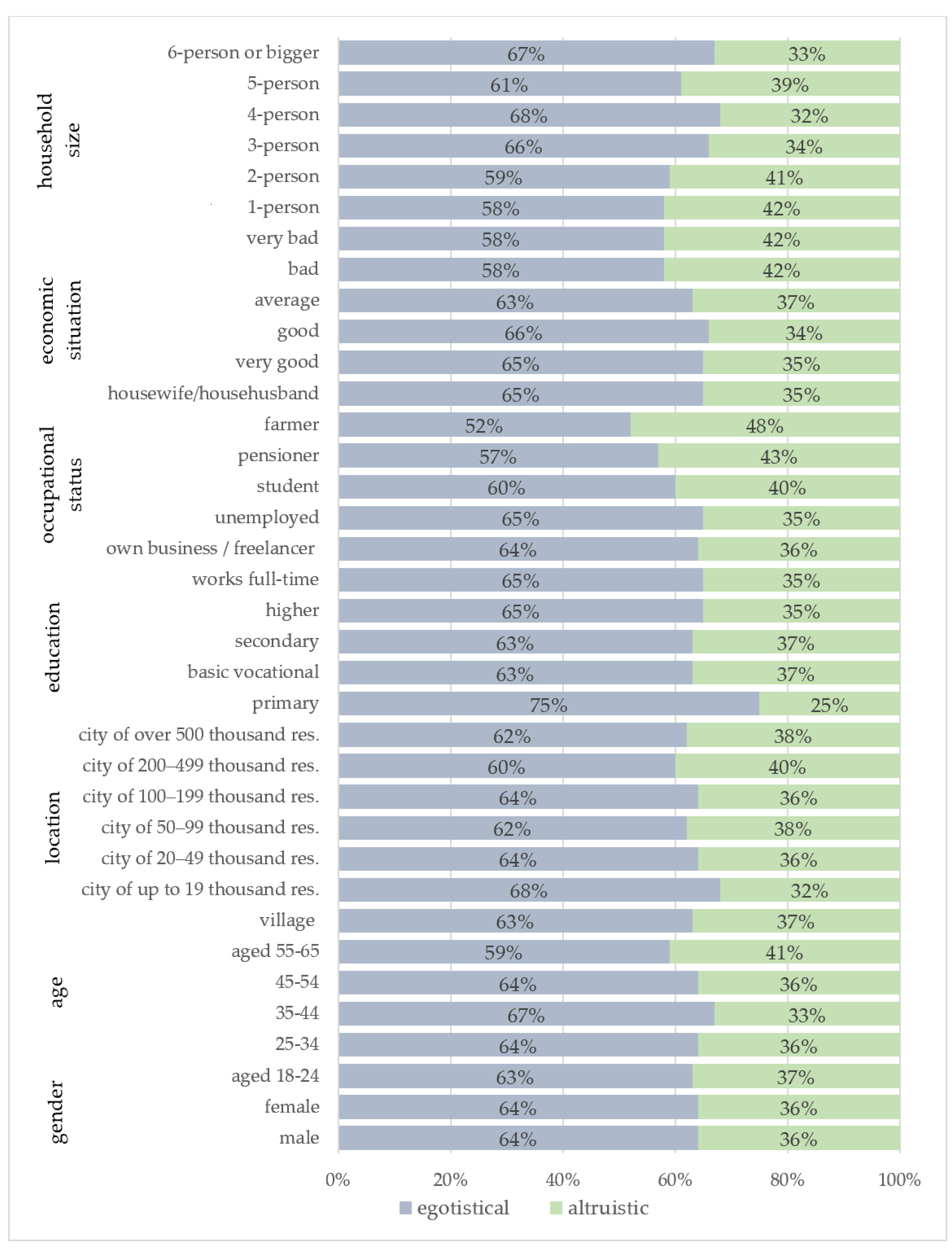

In turn, taking as the base the number of indications by respondents, 63.8% of all indications related to egotistical motives, while 36.2% of indications were for altruistic motives. In terms of the respondents’ characteristics (gender, age, class of place of residence, education, professional situation, economic situation and household size), egotistical motives dominated over altruistic motives (

Figure 1). Egotistical motives when purchasing ecological products were indicated more often by respondents of middle age (35–44) than younger respondents (18–24) and the oldest participants (55–65). Residents of small towns (up to 19,000 inhabitants) were more often driven by egotistical motives than residents of large cities (above 200,000 inhabitants) and medium-sized towns (50,000–99,000 inhabitants). People with the lowest level of education indicated egotistical motives more often than people from the higher levels. Among those working on full-time contracts and homemakers, the percentage of indications of egotistical motives was higher than for farmers, retirees/benefit recipients and pupils/students. Those who described their economic situation as very good or good gave egotistical motives for buying ecological products more often than those who considered their situation to be bad or very bad. Respondents from four-person, six-person and larger households were driven more often by egotistical motives than representatives of smaller households (one- or two-person). It should be added here that the test of proportion with Bonferroni correction did not confirm statistically significant differences between the indications given above.

The next aspect of the study into consumer behaviour was an analysis of the dependencies between the level of knowledge about ecological products and the purchase of ecological products.

The expression of consumers’ attitudes towards issues of ecology and ecological products is their interest in information about the current regulations regarding environmental protection. One in three of the respondents who had purchased an ecological product in the previous 3 months actively sought appropriate information on the internet, in the press and on television. Meanwhile, a slightly higher proportion (34%) indicated that they did not seek such information especially, but that they always paid attention to it if they noticed it in the digital or traditional media. Slightly fewer respondents (around 30%) declared that they try to obtain such information when it is useful for solving a specific problem they face related to the purchase and use of such products, or the disposal of post-consumption waste.

A key criterion for assessing information about ecological products is their reliability for consumers. For every second respondent, a measure of this reliability is a label confirming the receipt of an ecological certificate. This label is valued the most among consumers who had bought an ecological product in the previous 3 months, as indicated by 62.4% of representatives of this group. Meanwhile, such views were expressed by only 40.2% of respondents who did not declare the purchase of an ecological product in this period. The differences are similar between the studied groups of consumers in terms of the assessment of the second measure of the reliability of the information on the ecological nature of a product, i.e., the list of substances from which a product is made. This information was valued by 58.5% of buyers of ecological products, and only 42.4% of those who had not bought an ecological product within the previous 3 months.

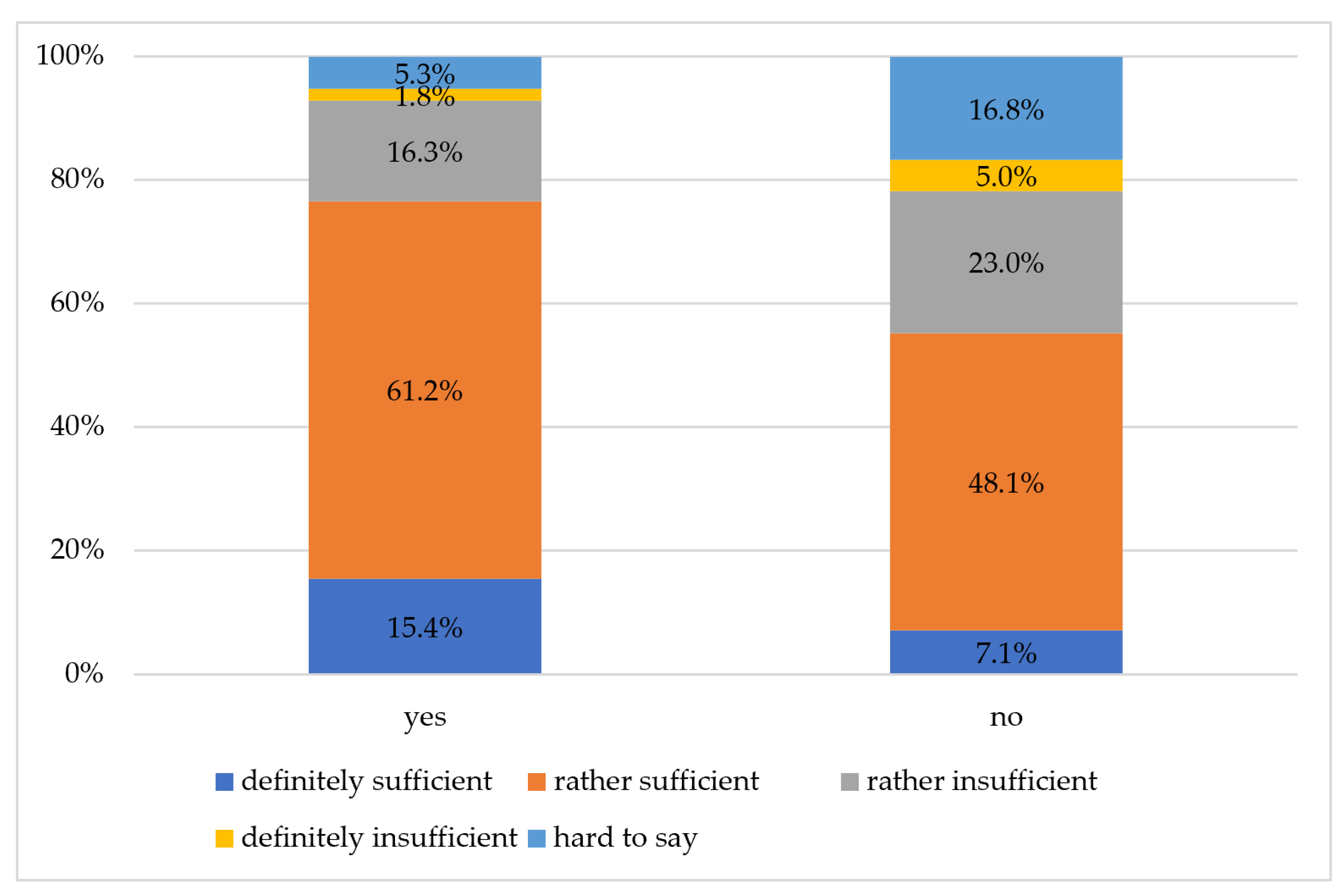

Respondents who had bought an ecological product as well as who had not, assessed their level of knowledge on the functioning of nature, the relationship between organisms and their environment, and the effect of humankind on the environment (in short, the functioning of the natural environment and the effect of humankind on it) as generally sufficient (61.2% and 48.1% of answers, respectively, in a given group), as shown in

Figure 2.

The applied chi-square independence test confirms the existence of dependencies between the assessment of the level of knowledge about the functioning of the natural environment and the effect of humankind on it, and the declared purchase (or not) of such a product. This is indicated by the statistically significant chi-square statistics value: χ2 (4, n = 1032) = 68.261; p < 0.000. The test of proportion indicated statistically significant (α = 0.05) differences in the frequency of responses: purchasers of ecological products more often than non-purchasers assessed their level of knowledge as definitely sufficient or mostly sufficient, while non-purchasers of ecological products more often than purchasers of such products assessed their level of knowledge as definitely insufficient, mostly insufficient or they found it hard to say.

In research into the factors shaping consumer behaviour on the market of ecological products, it is crucial to examine the reasons for limiting purchases or not making purchases of such products.

In their assessment of the importance of the factor that is the reason for limiting or not making such purchases, respondents used a seven-point scale (1—of very little importance, 7—of very great importance).

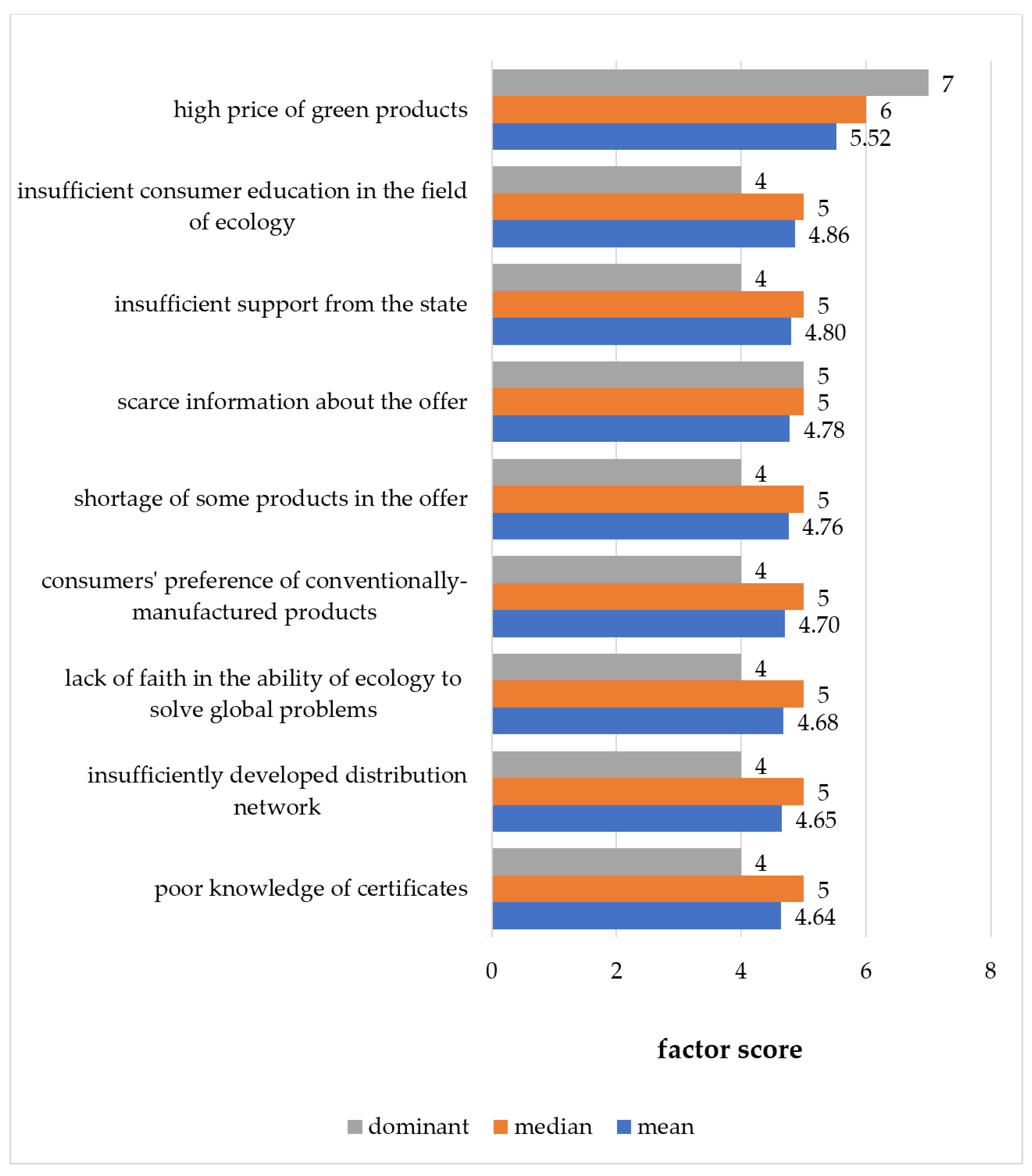

In analysing the reasons for limiting or not making purchases of ecological products in Poland, above all it is important to underline the high price of ecological products (5.51), which was indicated both by respondents who had purchased a product labelled with an ecological certificate in the previous 3 months, as well as those who had not made such a purchase. Close behind in second place among the barriers to purchasing ecological products, respondents indicated too little consumer education in the field of ecology, as the indicator expressing this was 4.85, and its role was especially valued by those who buy ecological products.

It must be emphasized that this is an important systemic factor, similar to the factor indicated in the next place, that is the lack of suitable support on the part of the state for the development of the ecological product market (4.80), as well as insufficient information about such products (4.77), and the unavailability of some products (4.76). Of relatively lesser importance in limiting the purchase and consumption of ecological products was the factor of preferring products produced in the conventional way (4.69), although it was indicated more often than factors such as insufficiently developed distribution network (4.63) and low knowledge about certification (4.61).

Worth noting is also the factor related to the lack of belief in the ability of ecology to solve global problems (4.65). This is an element of consumers’ mentality, which results from their considerable scepticism about the effectiveness of ecological action in saving the planet.

Figure 3 presents the basic consumer assessment parameters of individual factors limiting the purchase of ecological products. It turned out that all of them are of importance to the respondents, with the median assessment of the importance of a factor being 5. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicates that for every reason, the respondents’ median assessment is statistically significantly higher than 4 (with each test statistic of

p-value = 0.000).

It must be underlined that there is a consistency in the order of respondents’ assessments with regard to the reasons for limiting the purchase of ecological products, all Spearman rank correlation coefficients are positive and statistically significant at the level of 0.01 (

Table 4).

The dependencies are of average strength (coefficients with values exceeding 0.400, but not greater than 0.700). The strongest dependencies are between too little information about products on offer and too poorly developed distribution network (0.615), too little consumer education in the field of ecology (0.611), and the unavailability of some products (0.602). Insufficient market information about the ecological products on offer, therefore, has negative consequences for the shaping of consumers’ ecological awareness, as well as for the development of the distribution network, and ensuring a varied selection of such products.

In turn, the factor “high price of ecological products”—assessed by respondents as having the greatest importance—is correlated with “too little consumer education in the field of ecology” (0.496). Meanwhile, the low level of consumer education regarding ecology is related to a low level of knowledge about certification (0.599), and the lack of support from the state (0.588). These are understandable dependencies as only educated consumers aware of the importance of ecological products are likely to accept the relatively high prices of such products. In addition, there is an obvious link between consumers’ level of education and their knowledge of ecological certificates and ensuring the appropriate support of the state is a significant factor in shaping the ecological product market.

To determine the principal groups of factors seen by consumers to limit the sales of ecological products, exploratory factor analysis was conducted. The results related to limitations on development are presented in

Table 5.

In interpreting the results of exploratory factor analysis of the limitations perceived by consumers to limit the growth of the sales of ecological products (

Table 5), it must be noted that the first common factor—created by four variables—leads in terms of explaining the level of common variance (27.0%). This factor defines the limitations in access to ecological products. The second component, which includes two factors (21.3% of variance), of which “lack of support from the state” is highly correlated with this component, relates to the difficulty in obtained external organisational and legal support. The third common factor is linked to two variables connected to limitations related to undervaluing ecology. This factor explains 17.1% of the variance. Meanwhile, the fourth component identifies the price limitations of ecological products and includes only one variable with a high loading (0.846, explaining 12.5% of the common variance).

To obtain an answer to the research question regarding the assessment of the dependency between reasons for limiting or not making purchases and attitudes related to ecology, the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (rho) was used (

Table 6). Both questions contained answers measured on an ordinal scale (a 7-point scale for reasons: 1—low factor significance, 7—high factor significance; a seven-point scale for attitudes towards ecology: 1—I definitely disagree, 7—I definitely agree). There is consistency in the order of respondents’ answers, almost all of the Spearman rank correlation coefficients are positive and statistically significant at the level of at least 0.05. However, the dependencies are in the decided majority of low but distinct strength (coefficients with the values 0.200–0.399). The average strength of dependency occurs between the view “environmental protection does not require limiting consumption, it is enough to buy ecological products” and the reasons for limitations: ”high price of ecological products” (0.421), “too little consumer education about ecology” (0.413), and “lack of appropriate support from the state” (0.411). The high price of ecological products is also moderately correlated with the view that “the role of producers and sellers is to conduct their business in such a way as to create the least negative consequences for the natural environment as possible” (0.400). The expression of this view by respondents favours the acceptance of the high prices of ecological products, creating a challenge for producers and sellers.

It is also worth underlining the factor regarding the lack of support from the state, which is moderately correlated with the view that “thanks to creative internet users (bloggers, Youtubers), that is people who are active and known for their activities on the Internet, consumers can become consumers who pay more attention to ecology issues” (0.447). This is the highest coefficient correlation value. This dependency reveals the key role of Internet creators in shaping consumer attitudes towards ecology, as well as their behaviour on the ecological product market. This role is particularly important in situations when there is a lack of appropriate support from the state.

The factor indicated by respondents of lack of ecological products on offer is relatively strongly correlated with the view that the increase in the ecological products on offer and the introduction of new categories of products will lead to an increase in the consumption of ecological products (0.374). People who underlined the barrier of the availability of sought-after ecological products also more frequently expressed the opinion that the role of producers and sellers is to conduct their business in such a way as to create the least negative consequences for the natural environment as possible (0.342), and that the introduction of innovations should lead to reducing the negative effects of humankind on the environment (0.350). In addition, the factor of lack of products on offer is correlated even more strongly with the view of respondents that the role of the state is to create good conditions for the development of ecological products on offer (0.357). Consumers’ awareness of this dependence certainly indicates a key direction for the state’s pro-ecological policies.

Comprehensive analysis of the factors that shape consumers’ behaviour in the ecological product market also requires the inclusion of their opinions on the likelihood of this market developing. Analogically to the factors limiting or preventing purchases, respondents used a seven-point scale (1—very little significance, 7—very great significance) to assess the importance of factors treated as the likelihood of the sales of ecological products increasing.

The results show that changes in the awareness of consumers are considered by consumers to be a relatively important factor in increasing demand, and therefore the sale of ecological products in Poland. The indicator expressing this is 5.16, indicating a growing ecological awareness among consumers. The importance of this factor to a great degree is underlined by active purchasers of ecological products (5.35). These consumers also more often see the likelihood of the sales of ecological products developing thanks to state policies (5.22), which should favour the development of agriculture and the ecological product market. They also appreciate the importance of EU subsidies in creating conditions for increasing the sales of such products (5.17).

Of relatively lesser importance in the opinions of respondents are the relations between firms in the ecological product market, both between producers and distributors. However, they also point to the greater importance of cooperation between producers than between distributors. Meanwhile, in the relations between distributors, they indicate in particular the role of competition in stimulating market development and the growth of sales of ecological products. Exploratory factor analysis of the factors perceived by consumers to be opportunities for the development of the ecological product market enabled the extraction of three common factors (

Table 7). The first component is loaded with six variables, of which four have high factor loading, exceeding 0.7. This is the leading common factor as it covers 37.1% of the common variance. This component expresses the pro-ecological behaviour of consumers linked to the better availability of products.

The second component (explaining 20.6% of the variance) is loaded with two variables with high factor loadings. This component relates to the market competitiveness of producers and distributors. The third component is made up of two factors (EU subsidies and appropriate state policies). It explains 17.9% of the common variance and defines external financial and legal support.

The final part of the analysis into the factors shaping the attitudes and behaviour of consumers in the ecological product market focused on the conditions that must be fulfilled for the purchase of an ecological product. This was addressed depending on whether or not respondents had purchased ecological products in the previous three months.

The results show that the principal condition for increasing purchases of ecological food products is the price, which should only be slightly higher than the prices of conventional products. This was underlined by almost half of the respondents (48.7%) who had not purchased a product within the previous 3 months, i.e., considerably more than those who declared that they would buy such products if they were fully convinced of their nutritional value and good effect on health. This was indicated by one in three respondents (32.6%). To a considerably lesser degree, consumers depend on their decisions to purchase ecological products on the availability and structure of the products on offer, with only one in nine respondents indicating this (11.5%), and even fewer (7.3%) indications regarding the image of the producer and distributor. This results from the fact that the two fundamental conditions mentioned earlier overshadow the others, which are only subsequently considered as premises for purchases.

The research shows that 25.4% of consumers are willing to pay up to 10% more for an ecological product in comparison to a non-ecological product, while 20.7% of respondents would accept a price that is 10–15% higher. Greater differences in price, i.e., 15–30% are acceptable only to the smallest percentage of respondents (17.8%), with even higher prices, i.e., 30–50% only accepted by 11.6%. In this situation, it is comforting that only 16.4% declared that instead of an ecological product they choose a cheaper non-ecological product.

A statistically significant chi-square statistics value (compatibility test) was obtained for this group of respondents: χ2 (4, n = 524) = 234.092; p < 0.000, which confirms that the distribution of answers in this group of respondents is not equal. The differentiation between the categories of food purchases indicated by respondents of this group is high, with an answer distribution entropy of 0.833.

5. Discussion

Analysis of the quantitative study conducted among Polish consumers provided answers to the research questions posed on factors affecting the behaviour of consumers in the ecological product market. Recognising the significance and strength of such factors is very important in stimulating demand for ecological products, as currently, such products are only purchased by half of all consumers in Poland. This research, along with studies conducted by other authors [

71], demonstrates that consumers are driven in their behaviour on the ecological product market mainly by egotistical motives, in particular care for their own and their family’s health, as well as achieving well-being and pleasure from being in contact with nature. However, it must be emphasised that the growing ecological awareness of contemporary consumers is resulting in the motive of care for the environment being indicated increasingly frequently in research, with such results relating both to comestible and non-comestible ecological products. It is also worth studying the dependencies between egotistical and altruistic motives, especially in relation to ecological food.

Indicating the motive of care for the environment confirms an important trend in the behaviour of consumers, who ever more frequently declare their interest in sensitivity to ecological issues [

19]. For now, however, the motive of care for the environment, as well as other altruistic motives such as the need to support local producers and the effort to limit unemployment are dominated by egotistical motives connected to the direct, individual needs of consumers.

It should be emphasised that the basis for convincing consumers of the need to protect the environment and the effect of ecological products on their health and well-being is their level of knowledge about such products. This is confirmed in the research results, which show the positive dependency between respondents’ knowledge in this area and their purchase of ecological products. Consumers with a high and average level of knowledge and care for the environment also demonstrate a higher level of ecologically aware behaviour than consumers with a low level of knowledge and care for the environment [

72].

The author’s research has shown that although only one in three Polish consumers actively looks for appropriate information on the Internet, in the press and on television, a further 34% indicated that they always pay attention to such information if they are exposed to it in the digital or traditional media. This has an effect on deepening the level of knowledge about ecology and ecological products.

A key criterion in assessing information about ecological products is their reliability in the eyes of consumers [

73]. For every second respondent, the measure of such reliability is a label confirming the award of an ecological certificate. Ecological labels are an important source of consumer trust as they inform consumers about ecological products and the role of these products, i.e., they are environmentally friendly, they are beneficial to health, they motivate the consumer to make purchases, and they shape their conscious awareness [

40,

74].

Such labels are valued the most by consumers who systematically purchase ecological products, as indicated by 62.4% of respondents from this group. Meanwhile, this opinion was expressed by only 40.2% of respondents who declared they had not purchased an ecological product in the previous 3 months. The latter also display less interest in the list of substances from which the product is made, which is perceived by respondents as the second measure of the reliability of information about the ecological nature of a product. Studies by various authors clearly show the low level of knowledge about many labels among consumers, even though at the same time there is a need for reliable information about ecological products [

75]. This is a positive feature of the shaping of attitudes and behaviour in the ecological product market.

In light of the research, the main barrier to the purchase of ecological products still remains the high price of such products. While some authors [

53,

54] claim that it is not price but the readiness to pay a higher price for an ecological product compared to a conventional product that is of key importance in the decision to purchase an ecological product, Polish consumers are willing to accept prices that are only slightly higher than the prices of non-ecological products. This may be due to insufficient consumer education in the field of ecology, which can be the cause of too low ecological awareness among consumers. An increase in this awareness will certainly have an influence on the level of acceptance of higher prices for ecological products.

The research results show that the low level of consumer education is linked to a low level of knowledge about certificates, as well as the lack of appropriate support from the state. The lack of such support is perceived to be an important barrier to the development of the ecological product market, similar to insufficient information about the ecological products on offer and the lack of availability of some products. The correlation of these factors with the view of consumers that “environmental protection does not require limiting consumption, it is enough to buy ecological products” proves that according to the respondents, the natural environment can be protected without limiting purchases and consumption.

It can be supposed that the degree of acceptance among consumers with regard to the high prices of ecological products depends on their belief that producers and sellers conduct their activity in such a way as to have the least negative consequences for the natural environment. This is because there is a dependency between the high prices of ecological products as a barrier to the purchase of such products, and the above view about the way producers and sellers conduct their activity.

The reasons indicated by respondents for limiting the purchase of ecological products are demonstrated by statistically significant dependencies with the lifestyle value they declare, such as health, family life, love, safety and freedom. While these dependencies may be low, they are clear, and there are two factors that are the most strongly correlated with them, i.e., lack of appropriate support from the state, and the high price of ecological products. Other research has also shown that individualistic values such as an orientation towards health and safety, as well as hedonistic values, positively influence the purchase of ecological products [

76].

For respondents who value contact with nature as a lifestyle value, in addition to high prices, the reasons for limiting or not making purchases of ecological products is insufficient information about the products on offer, and too little consumer education in the field of ecology, as well as lack of appropriate support from the state. These factors are indicated even more often by those respondents for whom important values are acting on behalf of their surroundings.

In this context, it is necessary to define complete profiles of the consumers of ecological products, with emphasis not only on socio-demographic features, but also on cultural and psychographic characteristics. It would also be important to take into consideration social pressures, in particular groups referring to attitudes and behaviour with regard to ecological products. This is a limitation of the research procedure used. This requires further research. The results would enable producers and sellers to shape their offer and communication strategy to make them suited to each group of consumers, highlighting various elements that encourage the making of purchases depending on the nature of the ecological product.

An additional research limitation can also be the lack of references to research results in other countries, in particular in countries with a high level of socio-economic development. The authors are aware that such comparative analyses would make it possible to determine the distances between Polish consumers and consumers in these countries in terms of the growth in sales and consumption of ecological products. This was not, however, among the aims of this article.

Among the opportunities indicated by respondents as important for the development of the ecological product market, it is necessary to underline in particular the shaping of pro-ecological consumer behaviour based on their greater ecological awareness linked to the better availability and promotion of these products. It is vital to strengthen cooperation between the producers and distributors of ecological products in order to achieve the expected increase in the variety of products on offer. An important opportunity for the growth in demand and sales of ecological products can be seen in the improvement of the market competitiveness of producers and distributors, as this will result in the broadening and deepening of the offer, the improvement of quality, and the shaping of accessible prices for ecological products. Achieving such effects also requires appropriate policies on the part of the state, as well as external financial and legal support for firms, for example in the form of EU subsidies.

6. Conclusions

The main contribution of the research is the presentation of the importance of egotistical and altruistic motives and their effect on consumer behaviour in the ecological product market, as well as the factors that affect the limiting or lack of such purchases and those perceived by consumers to be opportunities for a growth in demand. When respondents’ characteristics are taken into account (gender, age, class of locality of residence, education, professional situation, economic situation and household size), egotistical motives dominate over altruistic motives. Indications by consumers of the high price of ecological products, too little consumer ecological education, as well as insufficient availability and lack of information about the ecological products on offer, allow the direction of action favouring an increase in demand for ecological products to be determined.

Consumer pro-ecological behaviour can be strengthened by improving their knowledge in the field of environmental protection and ecological labelling, as well as in green trust towards individual products [

77].

An important direction for action is ecological education, which is exceptionally important in shaping consumers’ ecological awareness. In addition to education in schools, as well as with the participation of the media in shaping an attitude of responsibility for the natural environment in every individual, a key role can also be played by the producers and distributors of ecological products. They should take care to ensure a suitable range of ecological products on offer, promote them appropriately, and conduct their activity with respect for the natural environment. It is important for such firms to apply appropriate forms of communication that persuade consumers to purchase ecological products.

The effectiveness of such action in shaping consumer attitudes depends on the skilful use of various forms of communication with clients, both via traditional and digital media. Ensuring the integrated place of ecological certificates in this communication increases their informative value and reliability in the eyes of clients. This research shows that consumers would be happier buying ecological products if they were fully convinced of their nutritious properties and their beneficial effect on health.

The poor labelling of ecological products is especially highlighted in emerging economies [

3]. Firms should therefore take action to increase trust in ecological products, as this has a positive effect (green trust) on consumer attitudes, and it is these attitudes that serve as a meaningful mediator between green trust and pro-ecological behaviour [

78].

Informing consumers about eco-labels is even more important as it has been shown that consumer attitudes towards environmental issues are unstable and are susceptible to being influenced by various messages [

77,

79]. This is important as eco-labels are a strategic communication tool, the aim of which is to shape positive attitudes and promote pro-ecological consumer behaviour.

Developing one’s knowledge about environmental problems and taking responsibility for the environment when making purchases is conducive to achieving a sustainable lifestyle in which the consumption of both comestible and non-comestible ecological products is crucial.

Increasing the number of ecological consumers who are driven by care for the natural environment and are truly interested in ecological products is a challenge both for public authorities and market entities. Firms that follow the practice of revealing information regarding environmental and social issues play an important part in raising the level of knowledge of consumers. At the same time, it has been proven that the greater transparency and responsibility of such firms help them to improve their profitability [

80]. Applying knowledge about the range of various consumer behaviours according to the basic features that characterise the consumers of ecological and non-ecological products, provides additional opportunities for those managing such communication. A real ecological consumer buys environmentally friendly products not because it is fashionable, but as a result of their interest in and care for their health and for ecological issues.

An important direction of future research should be exploring the propensity of clients to buy ecological products depending on individual lifestyles, and not only on the socio-demographic profile of consumers. This will assist in building appropriate marketing strategies, in particular market communication programmes.

A dependency was identified between the degree of acceptance by consumers of the high prices of ecological products and their belief that manufacturers and sellers were driven in their actions by care for the natural environment. This was an important factor in shaping their environmentally friendly actions. In addition, this allowed for appropriate directing of communication underlining companies’ principles of social responsibility.

In the age of the digital economy and the information society, it is extremely important for firms to use the potential of internet technology effectively, especially social media for sparking consumer interest and for persuading users to purchase ecological products. An important role can be played by influencers, as the relations between influencers and consumers feature perceived closeness, authenticity and trust. Young consumers and people with a low level of education are highly susceptible to the influence of marketing influencers. They are therefore easy to convince to purchase products on the market, including ecological products. However, attention must be paid to the message transparency factor and the revealing of any contractual agreement between the influencer and the brand being promoted, so as to exclude the risk of them acting on behalf of this brand. This is because the lack of objectivity in an influencer is a potential threat to users [

81].

In the case of people who are less active on the internet or do not use social media at all, firms should effectively use conventional media in order to reach this group more easily. It is also necessary to use the potential of digital media, including methods and strategies such as content marketing, in which action is taken to publish and promote content valuable for ecology and suitably adapted to the profile of a specific client segment. This makes it possible to build long-term and intensive relations with a selected group of clients, in time based on emotions. To achieve the desired effects, consistency must be ensured in messages broadcast via different communication channels.

It is also necessary to overcome the lack of belief declared by respondents in the possibility of ecology to solve global problems. The considerable scepticism among Poles with regard to the effectiveness of ecological actions may result from insufficient knowledge of good practices in saving the Earth.

After all, shaping trust in firms and ecological product brands is one of the key conditions for growth in demand and an increase in the sales of such products. For this reason, firms offering ecological products should act in the ecosystem and skillfully use external support from the European Union’s ecological policies that aim to change the model of production and consumption in the modern world.