EMA Implementation and Corporate Environmental Firm Performance: A Comparison of Institutional Pressures and Environmental Uncertainty

Abstract

:1. Introduction

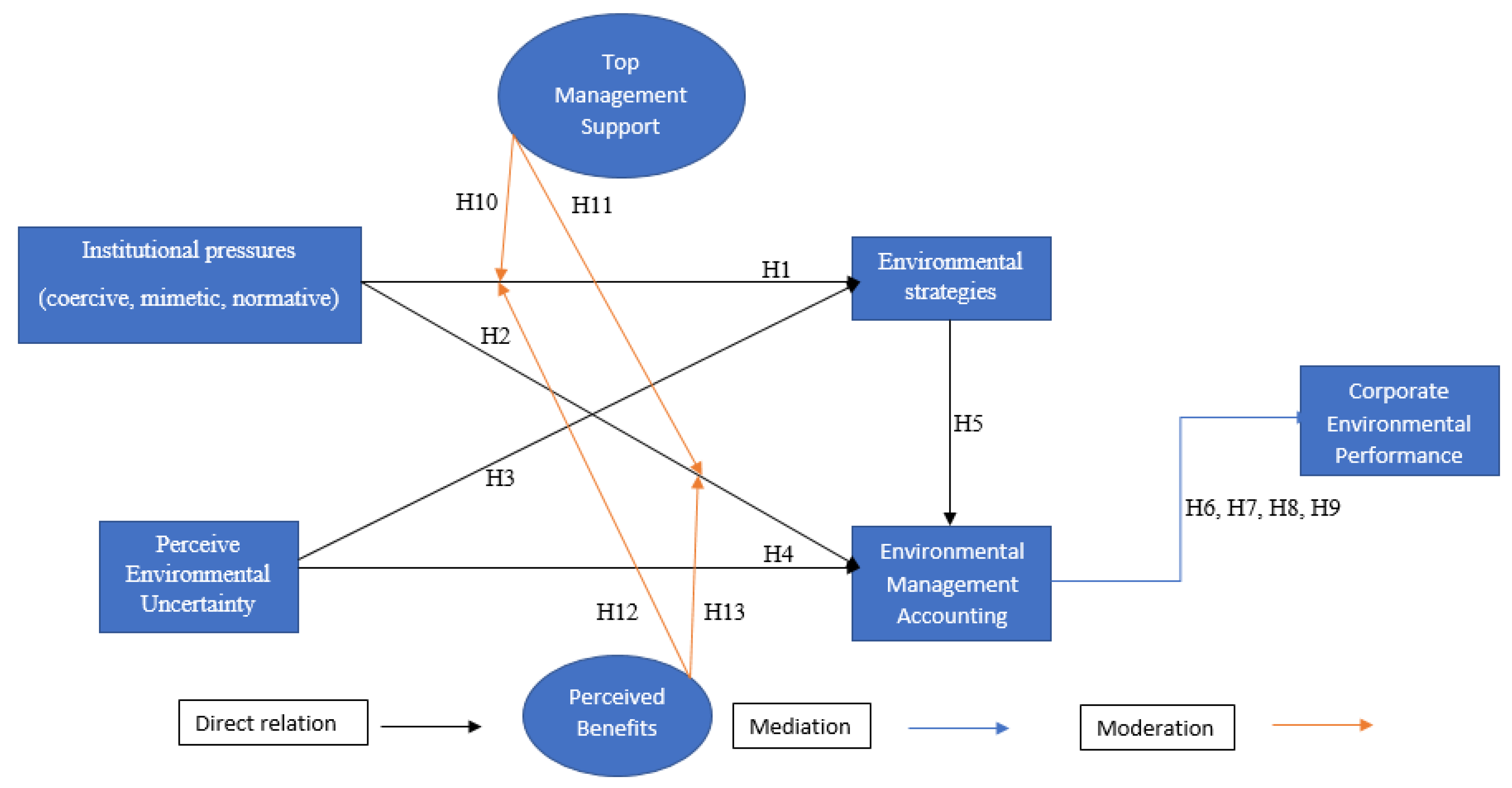

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Institutional Theory

2.2. Institutional Pressures and Environmental Strategy

2.3. Institutional Pressures and EMA Practices

2.4. Environmental Uncertainty, Environmental Strategy and EMA Practices

2.5. Environmental Strategies, Environmental Accounting and Corporate Environmental Performance

2.6. Mediating Relationships

2.7. Moderating Relationships

2.7.1. Top-Management Support

2.7.2. Perceived Benefits

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement of Various Constructs

3.3. Coercive Pressure, Normative and Mimetic Pressure

3.4. Perceived Environmental Uncertainty

3.5. Environmental Strategy

3.6. Environmental Management Accounting

3.7. Top-Management Support

3.8. Perceived Benefits

3.9. Corporate Environmental Performance

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model

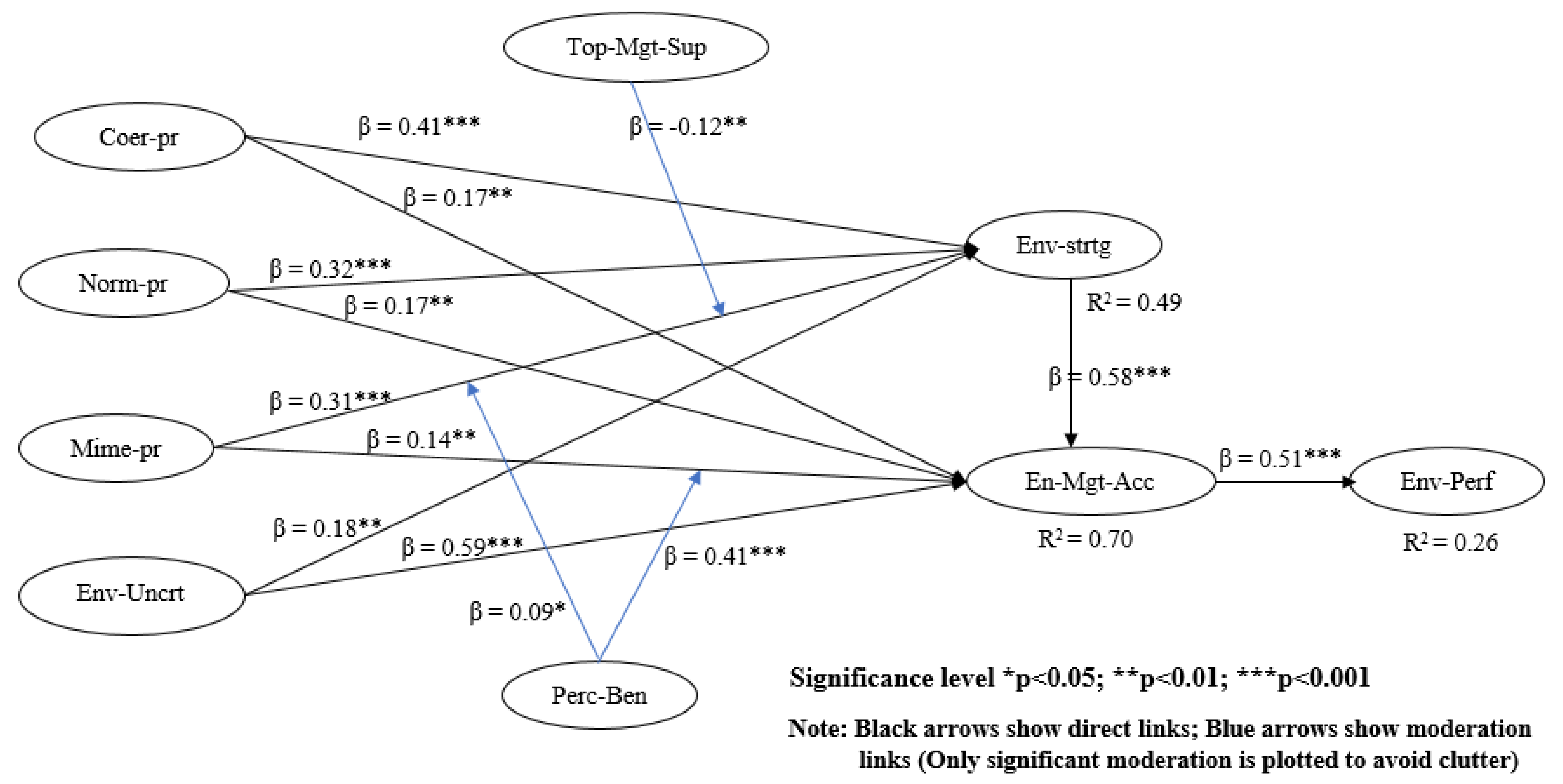

4.3. Assessment of Direct Effects

4.4. Assessment of Mediation Effects

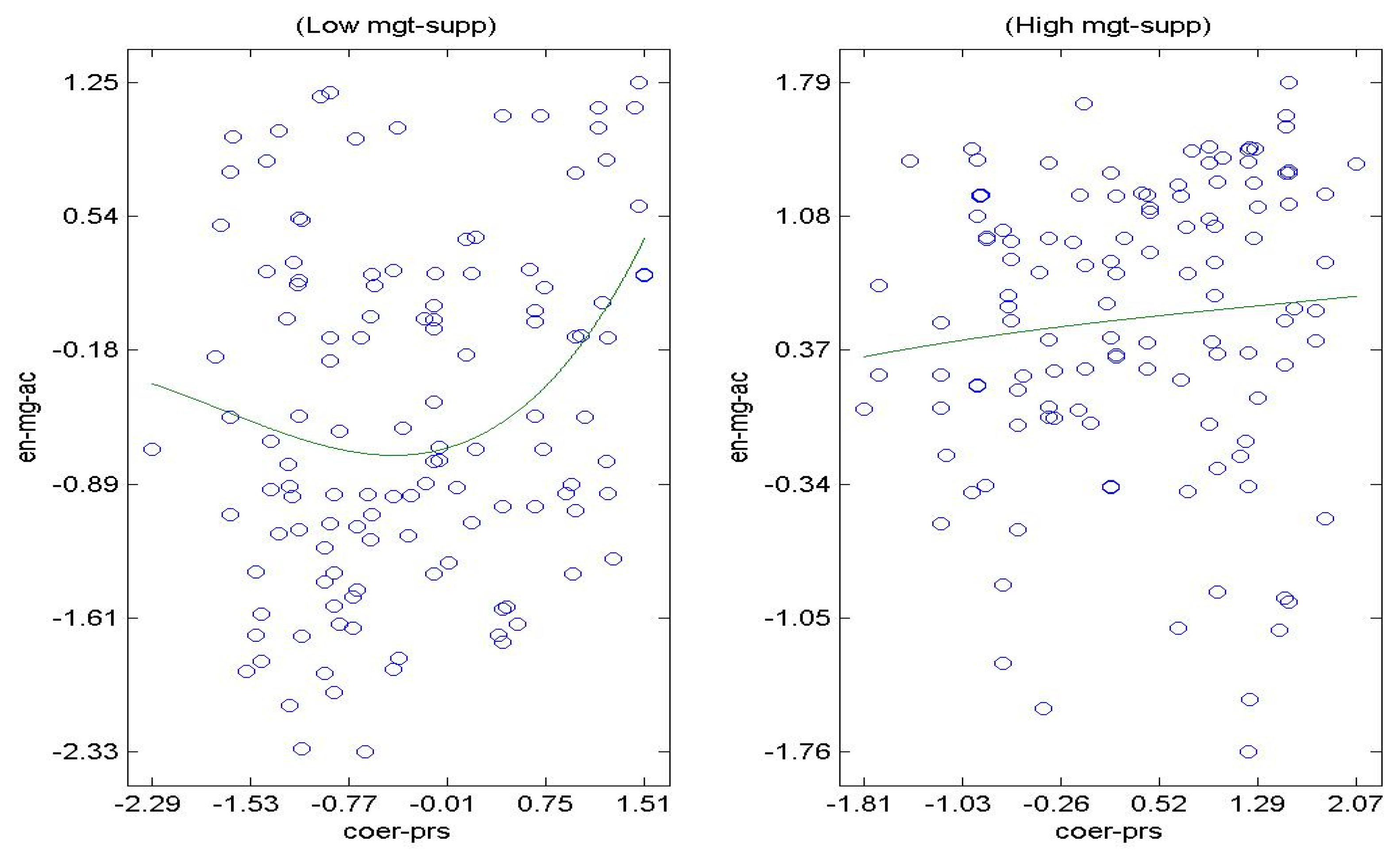

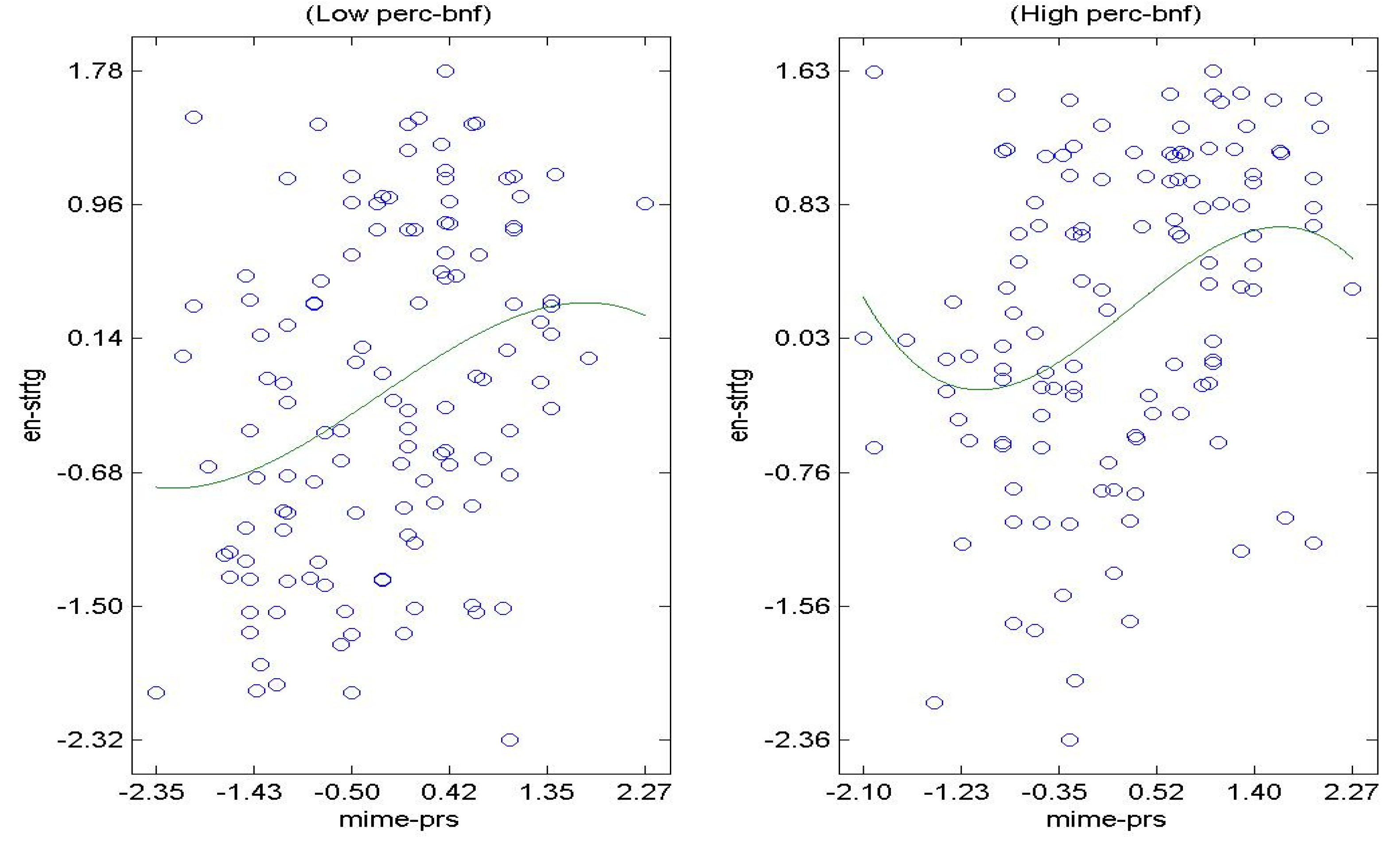

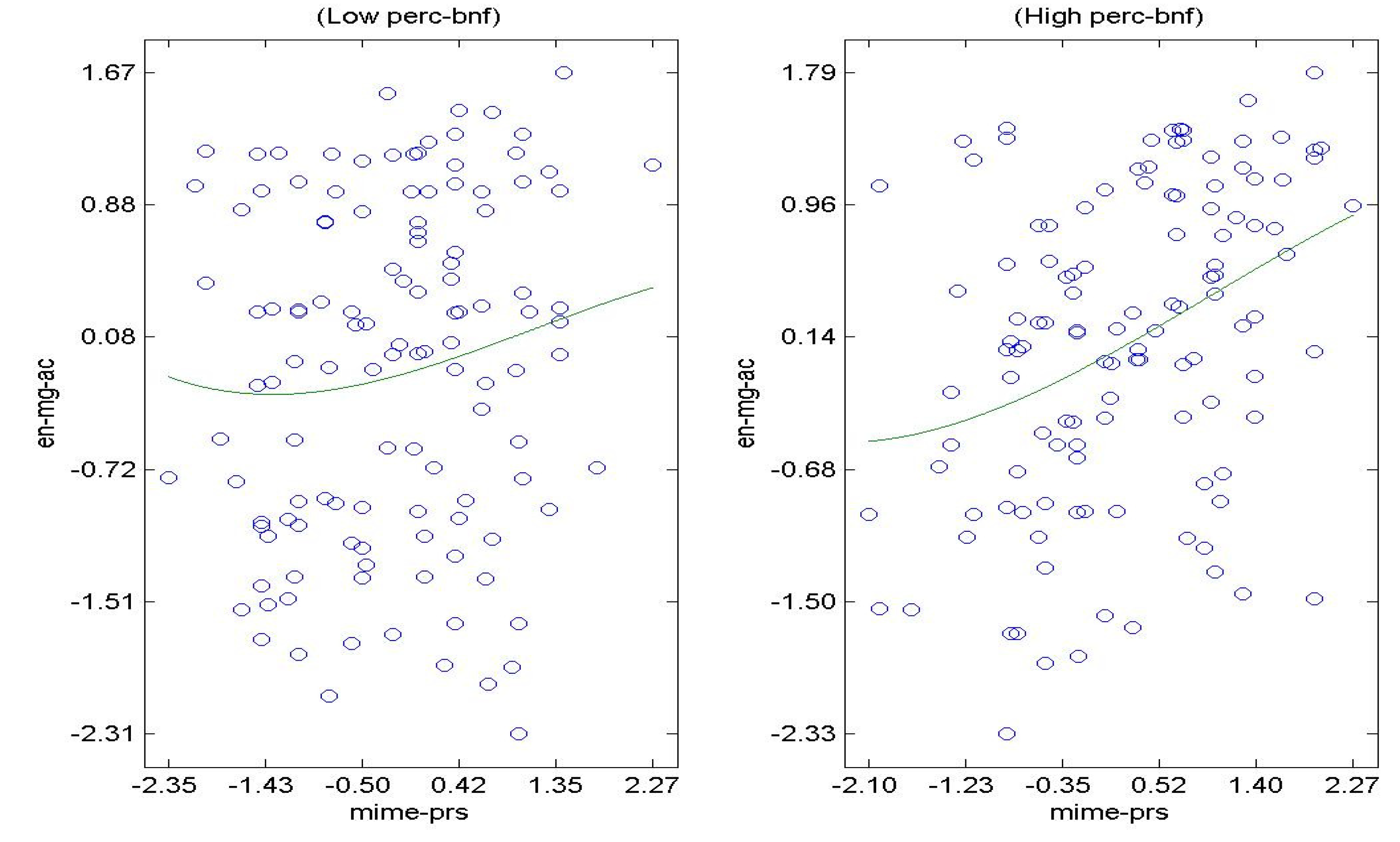

4.5. Assessment of Moderation Effects

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Research Implications

6.2. Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Important Variables and Conceptualizations

| Sr | Variables | Definition |

| 1 | Environmental management accounting (EMA) | “Management of environment and economic performance through the development and implementation of appropriate environmental-related accounting systems and practices” [6]. |

| 2 | Environmental uncertainty (EU) | “Environmental uncertainty refers to unpredictable circumstances or changes in prevailing market conditions causing the firm to actively respond the present or future challenges” [55]. |

| 3 | Environmental strategy (ES) | “Corporate EMS represents a set of initiatives implemented in an organization to reduce the environmental impact through products, processes, and corporate policies” [10]. |

| 4 | Environmental performance (EP) | “Environmental performance pertains to measures that aim at production of environment-friendly products, reduction of pollution and waste at source, managing the reduction of environmentally harmful materials, enhancements in energy efficiency” [63]. |

| 5 | Institutional pressures (IP) | “Institutional pressures are the pressures exerted by governments, professions, or society on organizations to adopt environmental management practices, beyond the technical efficiencies”. |

Appendix B. Measurement of Constructs

- Institutional Pressures

- Perceived environmental uncertainty [55]

- Environmental strategy [25]

- Environmental management accounting [3]

- Top management support [3]

- Perceived benefits [3]

- Corporate environmental performance [25]

References

- Lee, S.-Y.; Klassen, R.D. Firms’ Response to Climate Change: The Interplay of Business Uncertainty and Organizational Capabilities. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2016, 25, 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Christensen, P.; Li, W. Application of the WEAP model in strategic environmental assessment: Experiences from a case study in an arid/semi-arid area in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 198, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, J. Exploring the effects of institutional pressures on the implementation of environmental management accounting: Do top management support and perceived benefit work? Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2019, 28, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, H.; Zeng, S.; Ma, H.; Zeng, R.; Tam, V.W. An indicator system for evaluating megaproject social responsibility. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1415–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, N.E. Stages of Corporate Sustainability: Integrating the Strong Sustainability Worldview. Organ. Environ. 2018, 31, 287–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunarathne, A.N.; Lee, K.; Kaluarachchilage, P.K.H. Institutional pressures, environmental management strategy, and organizational performance: The role of environmental management accounting. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X. Effects of proactive environmental strategy on environmental performance: Mediation and moderation analyses. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 1438–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, I.E. Translating environmental motivations into performance: The role of environmental performance measurement systems. Manag. Account. Res. 2015, 29, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwood, T.J.; Lewellen, C. The Complementarity between Tax Avoidance and Manager Diversion: Evidence from Tax Haven Firms. Contemp. Account. Res. 2019, 36, 259–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gunarathne, N.; Lee, K.-H. Environmental Management Accounting (EMA) for environmental management and organizational change. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2015, 11, 362–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.; Moulang, C.; Hendro, B. Environmental management accounting and innovation: An exploratory analysis. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2010, 23, 920–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.N.; Baird, K.; Su, S.X. The use and effectiveness of environmental management accounting. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Othman, M.S.H.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P. The moderating role of environmental management accounting between environmental innovation and firm financial performance. Int. J. Bus. Perform. Manag. 2018, 19, 326–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovida, G.T.; Latan, H. Linking environmental strategy to environmental performance: Mediation role of environmental management accounting. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2017, 8, 595–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Kader, M.; Luther, R. The impact of firm characteristics on management accounting practices: A UK-based empirical analysis. Br. Account. Rev. 2008, 40, 2–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Burritt, R.L.; Chen, J. The potential for environmental management accounting development in China. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2015, 11, 406–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, R.N.; Pratadina, A.; Anugerah, R.; Kamaliah, K.; Sanusi, Z.M. Effect of environmental management accounting practices on organizational performance: Role of process innovation as a mediating variable. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2021, 27, 1296–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). Environmental Management Accounting-International Guidance Document. Available online: http://www.ioew.at/ioew/download/IFAC_Guidance_Env_Man_Acc_0508.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2016).

- Koppell, J. Handbook of Transnational Governance; Hale, T.N., Hale, T., Held, D., Eds.; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; Volume 41, p. 289. ISBN 0745650619. [Google Scholar]

- Burritt, R.L. Environmental reporting in Australia: Current practices and issues for the future. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2002, 11, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hart, S.L.; Dowell, G. Invited Editorial: A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm: Fifteen Years After. J. Manage. 2010, 37, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R.B. Characteristics of Organizational Environments and Perceived Environmental Uncertainty. Adm. Sci. Q. 1972, 17, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pawar, R.J.; Bromhal, G.S.; Carey, J.W.; Foxall, W.; Korre, A.; Ringrose, P.S.; Tucker, O.; Watson, M.N.; White, J.A. Recent advances in risk assessment and risk management of geologic CO2 storage. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2015, 40, 292–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Latan, H.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Jabbour, A.B.L.D.S.; Wamba, S.F.; Shahbaz, M. Effects of environmental strategy, environmental uncertainty and top management’s commitment on corporate environmental performance: The role of environmental management accounting. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A.A.; Jaaron, A.A.M.; Bon, A.T. The impact of green human resource management and green supply chain management practices on sustainable performance: An empirical study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baah, C.; Opoku-Agyeman, D.; Acquah, I.S.K.; Agyabeng-Mensah, Y.; Afum, E.; Faibil, D.; Abdoulaye, F.A.M. Examining the correlations between stakeholder pressures, green production practices, firm reputation, environmental and financial performance: Evidence from manufacturing SMEs. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 27, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karyawati, G.; Subroto, B.; Sutrisno, T.; Saraswati, E. Explaining the complexity relationship of CSR and financial performance using neo-institutional theory. J. Asian Bus. Econ. Stud. 2020, 27, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibin, K.T.; Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Hazen, B.; Roubaud, D.; Gupta, S.; Foropon, C. Examining sustainable supply chain management of SMEs using resource based view and institutional theory. Ann. Oper. Res. 2017, 290, 301–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Grisales, E.; Aguilera-Caracuel, J.; Guerrero-Villegas, J.; García-Sánchez, E. Does green innovation affect the financial performance of Multilatinas? The moderating role of ISO 14001 and R&D investment. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 3286–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitektine, A.; Lucas, J.W.; Schilke, O. Institutions under a microscope: Experimental methods in institutional theory. In Unconventional Methodology in Organization and Management Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Childe, S.J.; Papadopoulos, T.; Hazen, B.; Giannakis, M.; Roubaud, D. Examining the effect of external pressures and organizational culture on shaping performance measurement systems (PMS) for sustainability benchmarking: Some empirical findings. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 193, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, J.; Zhao, D. Institutional Pressures and Environmental Management Practices: The Moderating Effects of Environmental Commitment and Resource Availability. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018, 27, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, G. Promoting firms’ energy-saving behavior: The role of institutional pressures, top management support and financial slack. Energy Policy 2018, 115, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, B.; Mahmood, Z.; San, O.T.; Said, R.M.; Bakhsh, A. Coercive, Normative and Mimetic Pressures as Drivers of Environmental Management Accounting Adoption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, S.R.; Joshi, A.W. Corporate Ecological Responsiveness: Antecedent Effects of Institutional Pressure and Top Management Commitment and Their Impact on Organizational Performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berrone, P.; Fosfuri, A.; Gelabert, L.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Necessity as the mother of ‘green’ inventions: Institutional pressures and environmental innovations. Strat. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heugens, P.; Lander, M.W. Structure! Agency! (And Other Quarrels): A Meta-Analysis Of Institutional Theories of Organization. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, H.H.; Wei, K.K.; Benbasat, I. Predicting intention to adopt interorganizational linkages: An institutional perspective. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 27, 19–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brammer, S.; Hoejmose, S.; Marchant, K. Environmental Management in SMEs in the UK: Practices, Pressures and Perceived Benefits. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.; Toffel, M.W. Stakeholders and environmental management practices: An institutional framework. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2004, 13, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P. Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strat. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, A.; Haniffa, R. Evidence in development of sustainability reporting: A case of a developing country. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2011, 20, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Cordeiro, J.; Sarkis, J. Institutional pressures, dynamic capabilities and environmental management systems: Investigating the ISO 9000—Environmental management system implementation linkage. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 114, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windolph, S.E.; Schaltegger, S.; Herzig, C. Implementing corporate sustainability: What drives the application of sustainability management tools in Germany? Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2014, 5, 378–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Boiral, O.; Iraldo, F. Internalization of Environmental Practices and Institutional Complexity: Can Stakeholders Pressures Encourage Greenwashing? J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 147, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdifar, H.; Tsamenyi, M.; Granlund, M.; Forsaith, D.; Xydias-Lobo, M.; Tilt, C.; Ferreira, C.R.; Filipe, J.; Watts, T.; Mcnair, C.J.; et al. Accounting Innovations and Ownership; AAA 2011 Management Accounting Section (MAS) Meeting Paper. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1658340 (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Bansal, P. The corporate challenges of sustainable development. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2002, 16, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Environmental innovation practices and performance: Moderating effect of resource commitment. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Contributing to a Theoretical Research Program. In Great Minds in Management: The Process of Theory Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H.; Saraf, N.; Hu, Q.; Xue, Y. Assimilation of enterprise systems: The effect of institutional pressures and the mediating role of top management. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 31, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, C.H.S.; Cannon, A.R.; Pouder, R.W. Change drivers in the new millennium: Implications for manufacturing strategy research. J. Oper. Manag. 2001, 19, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Sustainable competitive advantage: Combining institutional and resource-based views. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pondeville, S.; Swaen, V.; De Rongé, Y. Environmental management control systems: The role of contextual and strategic factors. Manag. Account. Res. 2013, 24, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.J.; Harvey, B. Perceived Environmental Uncertainty: The Extension of Miller’s Scale to the Natural Environment. J. Manag. Stud. 2001, 38, 201–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadman, T.; Maraseni, T.; Breakey, H.; López-Casero, F.; Ma, H.O. Governance Values in the Climate Change Regime: Stakeholder Perceptions of REDD+ Legitimacy at the National Level. Forests 2016, 7, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soleimani, G.; Majbouri Yazdi, H. The Impact of Environmental Strategy, Environmental Uncertainty and Leadership Commitment on Corporate Environmental Performance: The Role of Environmental Management Accounting. Manag. Account. 2019, 12, 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Adomako, S.; Ning, E.; Adu-Ameyaw, E. Proactive environmental strategy and firm performance at the bottom of the pyramid. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, A.A.; Fremeth, A.R. Strategic direction and management. In Business Management and Environmental Stewardship: Environmental Thinking as a Prelude to Management Action; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009; pp. 38–55. [Google Scholar]

- Danso, A.; Adomako, S.; Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Owusu-Agyei, S.; Konadu, R. Environmental sustainability orientation, competitive strategy and financial performance. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 28, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, A.X.; Zhou, K.Z.; Jiang, W. Environmental Strategy, Institutional Force, and Innovation Capability: A Managerial Cognition Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 159, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, E.; Endrikat, J.; Guenther, T.W. Environmental management control systems: A conceptualization and a review of the empirical evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, M.; Magnan, M.; Boulianne, E. Stakeholders’ influence on environmental strategy and performance indicators: A managerial perspective. Manag. Account. Res. 2013, 24, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daddi, T.; Testa, F.; Frey, M.; Iraldo, F. Exploring the link between institutional pressures and environmental management systems effectiveness: An empirical study. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 183, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, M.; Chaudhry, N.I. Linking environmental strategy to firm performance: A sequential mediation model via environmental eanagement accounting and top management commitment. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2019, 13, 849–867. [Google Scholar]

- Betts, T.K.; Super, J.F.; North, J. Exploring the influence of institutional pressures and production capability on the environmental practices—Environmental performance relationship in advanced and developing economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 1082–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Bae, J.; Lee, J.; Lee, C.-S.; Hong, S.; Wang, Z.L. Self-powered environmental sensor system driven by nanogenerators. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 3359–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erauskin-Tolosa, A.; Zubeltzu-Jaka, E.; Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Boiral, O. ISO 14001, EMAS and environmental performance: A meta-analysis. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 29, 1145–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, E.; Newbold, A.; Tester-Jones, M.; Javaid, M.; Cadman, J.; Collins, L.; Graham, J.; Mostazir, M. Implementing multifactorial psychotherapy research in online virtual environments (IMPROVE-2): Study protocol for a phase III trial of the MOST randomized component selection method for internet cognitive-behavioural therapy for depression. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burritt, R.L.; Schaltegger, S. Sustainability accounting and reporting: Fad or trend? Account. Audit. Account. J. 2010, 23, 829–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, K.; Burritt, R.L. Environmental management accounting: The significance of contingent variables for adoption. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 41, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunk, A. Assessing the Effects of Product Quality and Environmental Management Accounting on the Competitive Advantage of Firms. Australas. Bus. Account. Financ. J. 2007, 1, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burritt, R.L.; Herzig, C.; Tadeo, B.D. Environmental management accounting for cleaner production: The case of a Philippine rice mill. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.; Nilsson, J.; Modig, F.; Vall, G.H. Commitment to Sustainability in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: The Influence of Strategic Orientations and Management Values. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2017, 26, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.N.; Baird, K. The comprehensiveness of environmental management systems: The influence of institutional pressures and the impact on environmental performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 160, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kock, N.; Hadaya, P. Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and gamma-exponential methods. Inf. Syst. J. 2016, 28, 227–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Analysis; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Jaafar, M.; Kock, N.; Ahmad, A.G. The effects of community factors on residents’ perceptions toward World Heritage Site inscription and sustainable tourism development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 25, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitsaz, E.; Liang, D.; Khoshsoroor, S. The impact of resource configuration on Iranian technology venture performance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 122, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M.S.; Wang, M.; Mumtaz, M.U.; Ahmed, Z.; Zaki, W. What attracts me or prevents me from mobile shopping? An adapted UTAUT2 model empirical research on behavioral intentions of aspirant young consumers in Pakistan. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2021, 34, 1031–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, K.; Verbeke, A. Proactive environmental strategies: A stakeholder management perspective. Strat. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Deegan, C. Exploring factors influencing environmental management accounting adoption at RMIT university. In Proceedings of the Sixth Asia Pacific Interdisciplinary Research in Accounting (APIRA) conference, Sydney, Australia, 12–13 July 2010; Volume 26, pp. 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wijethilake, C. Proactive sustainability strategy and corporate sustainability performance: The mediating effect of sustainability control systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 196, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Gaskins, L. The Mediating Role of Voice and Accountability in the Relationship Between Internet Diffusion and Government Corruption in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2013, 20, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubilla-Montilla, M.I.; Galindo-Villardón, P.; Nieto-Librero, A.B.; Galindo, M.P.V.; García-Sánchez, I.M. What companies do not disclose about their environmental policy and what institutional pressures may do to respect. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 27, 1181–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Cin, B.C.; Lee, E.Y. Environmental Responsibility and Firm Performance: The Application of an Environmental, Social and Governance Model. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2016, 25, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Schaltegger, S. The Effect of Corporate Environmental Strategy Choice and Environmental Performance on Competitiveness and Economic Performance: An Empirical Study of EU Manufacturing. Eur. Manag. J. 2004, 22, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Journeault, M. The Influence of the Eco-Control Package on Environmental and Economic Performance: A Natural Resource-Based Approach. J. Manag. Account. Res. 2016, 28, 149–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, M.S.; Yunfei, S.; Hanif, M.I.; Junaid, D. Dynamics of Late-Career Entrepreneurial Intentions in Pakistan—Individual and Synergistic Application of Various Capital Resources and Fear of Failure. Entrep. Res. J. 2021, 10151520180062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.K.; Panda, A.; Choudhary, P. Institutional pressures and circular economy performance: The role of environmental management system and organizational flexibility in oil and gas sector. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 3509–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Nguyen, T.M.A.; Phan, T.T.H. Environmental Management Accounting and Performance Efficiency in the Vietnamese Construction Material Industry—A Managerial Implication for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, S.K.; Chen, J.; Del Giudice, M.; El-Kassar, A.-N. Environmental ethics, environmental performance, and competitive advantage: Role of environmental training. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 146, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Firm-Related Characteristics (N = 243) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Firm Characteristic | Category | Frequency | % Age |

| Firm age | <10 years | 50 | 20.58 |

| 10 to 15 years | 74 | 30.45 | |

| 15 to 20 years | 80 | 32.92 | |

| >20 years | 39 | 16.05 | |

| Industry/sector | Agriculture and food | 26 | 10.70 |

| Appliances and equipment manufacturing | 41 | 16.87 | |

| Mechanical and metallurgical engg. | 61 | 25.10 | |

| Chemical and energy | 33 | 13.58 | |

| Electronics and telecom | 42 | 17.28 | |

| Textile | 25 | 10.29 | |

| Pharmaceutical | 15 | 6.17 | |

| Ownership structure | State owned | 25 | 10.29 |

| Private | 45 | 18.52 | |

| Foreign controlled | 80 | 32.92 | |

| Joint venture | 93 | 38.27 | |

| Firm size (total employees) | <500 | 42 | 17.28 |

| 500 to 1000 | 46 | 18.93 | |

| 1001 to 2000 | 79 | 32.51 | |

| >2000 | 76 | 31.28 | |

| Construct | CP | NP | MP | PEU | ES | EMA | TMS | PB | CEP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP | 0.831 | 0.237 | 0.224 | 0.433 | 0.466 | 0.284 | 0.375 | 0.272 | 0.435 |

| NP | 0.237 | 0.844 | 0.208 | 0.47 | 0.407 | 0.272 | 0.369 | 0.233 | 0.483 |

| MP | 0.224 | 0.208 | 0.821 | 0.448 | 0.362 | 0.262 | 0.353 | 0.247 | 0.475 |

| PEU | 0.433 | 0.47 | 0.448 | 0.799 | 0.18 | 0.495 | 0.38 | 0.234 | 0.618 |

| ES | 0.466 | 0.407 | 0.362 | 0.18 | 0.801 | 0.474 | 0.357 | 0.228 | 0.328 |

| EMA | 0.284 | 0.272 | 0.262 | 0.495 | 0.474 | 0.807 | 0.65 | 0.175 | 0.508 |

| TMS | 0.375 | 0.369 | 0.353 | 0.38 | 0.357 | 0.65 | 0.814 | 0.338 | 0.53 |

| PB | 0.272 | 0.233 | 0.247 | 0.234 | 0.228 | 0.175 | 0.338 | 0.871 | 0.445 |

| CEP | 0.435 | 0.483 | 0.475 | 0.618 | 0.328 | 0.508 | 0.53 | 0.445 | 0.783 |

| S No | Construct | Item | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha Value | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Coercive pressure | CP1 | 0.821 | 0.851 | 0.899 | 0.691 |

| CP2 | 0.847 | |||||

| CP3 | 0.832 | |||||

| CP4 | 0.825 | |||||

| 2 | Normative pressure | NP1 | 0.829 | 0.866 | 0.908 | 0.713 |

| NP2 | 0.826 | |||||

| NP3 | 0.864 | |||||

| NP4 | 0.858 | |||||

| 3 | Mimetic pressure | MP1 | 0.782 | 0.839 | 0.892 | 0.674 |

| MP2 | 0.819 | |||||

| MP3 | 0.843 | |||||

| MP4 | 0.838 | |||||

| 4 | Perceived environmental uncertainty | PEU1 | 0.78 | 0.905 | 0.925 | 0.639 |

| PEU2 | 0.803 | |||||

| PEU3 | 0.844 | |||||

| PEU4 | 0.74 | |||||

| PEU5 | 0.794 | |||||

| PEU6 | 0.836 | |||||

| PEU7 | 0.795 | |||||

| 5 | Environmental strategy | ES1 | 0.819 | 0.906 | 0.926 | 0.641 |

| ES2 | 0.782 | |||||

| ES3 | 0.87 | |||||

| ES4 | 0.804 | |||||

| ES5 | 0.773 | |||||

| ES6 | 0.804 | |||||

| ES7 | 0.746 | |||||

| 6 | Environmental management accounting | EMA1 | 0.773 | 0.892 | 0.918 | 0.651 |

| EMA2 | 0.842 | |||||

| EMA3 | 0.799 | |||||

| EMA4 | 0.841 | |||||

| EMA5 | 0.834 | |||||

| EMA6 | 0.748 | |||||

| 7 | Top-management support | TMS1 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.887 | 0.663 |

| TMS2 | 0.8 | |||||

| TMS3 | 0.772 | |||||

| TMS4 | 0.823 | |||||

| 8 | Perceived benefits | PB1 | 0.898 | 0.894 | 0.926 | 0.759 |

| PB2 | 0.839 | |||||

| PB3 | 0.863 | |||||

| PB4 | 0.883 | |||||

| 9 | Corporate environmental performance | CEP1 | 0.758 | 0.894 | 0.917 | 0.612 |

| CEP2 | 0.813 | |||||

| CEP3 | 0.8 | |||||

| CEP4 | 0.797 | |||||

| CEP5 | 0.765 | |||||

| CEP6 | 0.809 | |||||

| CEP7 | 0.732 |

| Model-Fit Indices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Indices | Value | Comments |

| Average path coefficient (APC) | 0.158 | p < 0.001 |

| Average R-squared (ARS) | 0.484 | p < 0.001 |

| Average adjusted R-squared (AARS) | 0.468 | p < 0.001 |

| Average block VIF (AVIF) | 1.376 | Acceptable if <= 5, ideally <= 3.3 |

| Average full collinearity VIF (AFVIF) | 2.004 | Acceptable if <= 5, ideally <= 3.3 |

| Tenenhaus GoF (GoF) | 0.632 | Small >= 0.1, medium >= 0.25, large >= 0.36 |

| Sympson’s paradox ratio (SPR) | 0.769 | Acceptable if >= 0.7, ideally = 1 |

| R-squared contribution ratio (RSCR) | 0.981 | Acceptable if >= 0.9, ideally = 1 |

| Statistical suppression ratio (SSR) | 0.923 | Acceptable if >= 0.7 |

| Nonlinear bivariate causality direction ratio (NLBCDR) | 0.712 | Acceptable if >= 0.7 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Path Coefficient | Standard Error | Effect Size | Status of Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | CP → ES | 0.413 *** | 0.060 | 0.191 | Supported |

| NP → ES | 0.320 *** | 0.061 | 0.131 | Supported | |

| MP → ES | 0.307 *** | 0.061 | 0.114 | Supported | |

| H2 | CP → EMA | 0.171 ** | 0.062 | 0.050 | Supported |

| NP → EMA | 0.168 ** | 0.061 | 0.046 | Supported | |

| MP → EMA | 0.142 * | 0.062 | 0.039 | Supported | |

| H3 | PEU → ES | 0.184 ** | 0.062 | 0.038 | Supported |

| H4 | PEU → EMA | 0.587 *** | 0.058 | 0.294 | Supported |

| H5 | ES → EMA | 0.576 *** | 0.058 | 0.274 | Supported |

| EMA → CEP | 0.509 *** | 0.059 | 0.259 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Direct Effect | Effect Size | Indirect Effect | Effect Size | Total Effect | Status of Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP → EMA | 0.171** | 0.050 | |||||

| CP→ES→EMA | 0.237 *** | 0.069 | 0.408 *** | ||||

| H6 | CP→EMA→CEP | 0.087 * | 0.038 | Supported | |||

| H7 | CP→ES→EMA→CEP | 0.12 *** | 0.052 | 0.207 *** | Supported | ||

| NP → EMA | 0.168 ** | 0.046 | |||||

| NP→ES→EMA | 0.184 *** | 0.051 | 0.352 *** | ||||

| H6 | NP→EMA→CEP | 0.085 * | 0.041 | Supported | |||

| H7 | NP→ES→EMA→CEP | 0.094 ** | 0.045 | 0.179 *** | Supported | ||

| MP → EMA | 0.142* | 0.039 | |||||

| MP→ES→EMA | 0.177 *** | 0.048 | 0.319 *** | ||||

| H6 | MP→EMA→CEP | 0.072 n.s. | 0.034 | Not supported | |||

| H7 | MP→ES→EMA→CEP | 0.09 ** | 0.043 | 0.162 *** | Supported | ||

| PEU → EMA | 0.587 *** | 0.294 | |||||

| PEU→ES→EMA | 0.106 ** | 0.053 | 0.693 *** | ||||

| H8 | PEU→EMA→CEP | 0.299 *** | 0.185 | Supported | |||

| H9 | PEU→ES→EMA→CEP | 0.054 n.s. | 0.033 | 0.353 *** | Not supported |

| Hypothesis | Path | Path Coefficient | p-Value | Status of Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H10 | TMS on [CP → ES] | −0.029 | n.s. | Not supported |

| TMS on [NP → ES] | 0.003 | n.s. | Not supported | |

| TMS on [MP → ES] | −0.007 | n.s. | Not supported | |

| H11 | TMS on [CP → EMA] | −0.119 | ** | Supported |

| TMS on [NP → EMA] | 0.033 | n.s. | Not supported | |

| TMS on [MP → EMA] | −0.064 | n.s. | Not supported | |

| H12 | PB on [CP → ES] | 0.053 | n.s. | Not supported |

| PB on [NP → ES] | −0.068 | n.s. | Not supported | |

| PB on [MP → ES] | 0.089 | * | Supported | |

| H13 | PB on [CP → EMA] | 0.060 | n.s. | Not supported |

| PB on [NP → EMA] | 0.017 | n.s. | Not supported | |

| PB on [MP → EMA] | 0.110 | ** | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kong, Y.; Javed, F.; Sultan, J.; Hanif, M.S.; Khan, N. EMA Implementation and Corporate Environmental Firm Performance: A Comparison of Institutional Pressures and Environmental Uncertainty. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095662

Kong Y, Javed F, Sultan J, Hanif MS, Khan N. EMA Implementation and Corporate Environmental Firm Performance: A Comparison of Institutional Pressures and Environmental Uncertainty. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):5662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095662

Chicago/Turabian StyleKong, Yusheng, Fahad Javed, Jahanzaib Sultan, Muhammad Shehzad Hanif, and Noheed Khan. 2022. "EMA Implementation and Corporate Environmental Firm Performance: A Comparison of Institutional Pressures and Environmental Uncertainty" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 5662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095662

APA StyleKong, Y., Javed, F., Sultan, J., Hanif, M. S., & Khan, N. (2022). EMA Implementation and Corporate Environmental Firm Performance: A Comparison of Institutional Pressures and Environmental Uncertainty. Sustainability, 14(9), 5662. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095662