1. Introduction

At present, sex education continues to be a pending subject in the Spanish education system in its different levels. In education centers, it is optional for the education community, lacking differentiated criteria and objectives based on scientific evidence [

1]. In Secondary School, it is possible to find sex education experiences; however, most of them reproduce the prevention-medical model, which is exclusively directed towards avoiding risks that are inherent to sexual activity [

1,

2,

3,

4]. On its part, the university system has not clearly included sex education-related training of their future professionals, despite the associated indications found in the current Organic Law 2/2010, from March 3rd, on Sexual and Reproductive Health, and Voluntary Interruption of Pregnancy [

5]. Not many universities and university degrees work on sex education [

6,

7,

8]. Those that do, however, do so as an option, or within the subject of

gender, ignoring other important aspects of the sex dimension, despite many studies urging the need for an intervention in Sex Education in formal education settings [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Training in sexuality at a university level is very scarce in relation to the number of universities in Spain and the number of degrees that are offered in each of them. Training in sexuality might not be feasible in all university degrees. However, it should be considered necessary in all those that are dedicated to socio-educational and/or clinical action, in short, those that involve working with people.

The evolution of society has also led to the evolution of sexuality, until arriving at the

Reino de la Libertad (Kingdom of Freedom) [

2]. However, it is evident that freedom can only be exerted with knowledge, increasingly so, in an area plagued with myths, contradictions, and pejorative loads that hinder its enjoyment and full development. The knowledge learned through a continuous educational process for health can contribute to the re-enforcement of personality and self-esteem, to achieve identity, and ease the adoption of positive attitudes towards affectivity, the relationships with others, sexuality, etc., [

13,

14,

15].

The abundant literature on sexuality of adolescents and young people shows the tendency to match sexuality with adolescence [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. This means that the scientific society, from the end of the 20th century until now, has been deeply interested in the sexual behaviors of adolescents [

23]. Overall, the data provided by these studies are not accompanied by proposals of education intervention, so that it is important to reflect on why and for what reason it is important to know about the sexual behaviors of adolescents [

24,

25]. That is, purposely thinking about the sense of providing information about the risky behaviors and other behaviors reproduced by the patriarchal gender roles, without planning acts of transformation, continue to be a challenge.

Proposed interventions in undergraduate curricula subjects on gender and/or equality should be extended to include the spectrum of sexuality, in order to understand, value, and accept diversity in the broad sense of the word; to be able to live sexuality in a healthy way. In this regard, a training program was carried out with subsequent research. The duration and structure of the training program, both in-person and virtual, were based on collaborative learning. The general objective of this training is none other than to provide students with the necessary tools to address educational intervention in sexuality and gender. Therefore, it is designed to respond to a large number of students who, throughout their different degrees, identify the need for additional, specific training in a field as broad as sexuality and gender. In the same way, and as the results of previous publications have shown, it also generates a great deal of interest among health professionals who see how, day to day, they are forced to provide answers or set up programs for health service users, without having the appropriate tools to do so. Education professionals are calling for more training in sexuality, as this is a transversal issue included in our educational laws and recognize their limitations when it comes to responding to or implementing training programs appropriate for the different educational levels.

With the problem of the present study described, the following objectives and working hypotheses are defined:

General Objective:

To assess the degree of knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of the university population associated to the dimension of sex before the implementation of two training activities and one after it, at three different moments in time, and to detect if there are significant differences after the training process.

For this, the following Specific Objectives are set:

- (a)

To detect if there was an increase in knowledge about sexuality.

- (b)

To verify if there were significant differences in the attitude of the students with respect to sexuality and sex education.

- (c)

To analyze if there were changes with respect to the attitudes towards gender-based violence, and intercultural sentimental relationships.

Starting with these objectives, the following General Hypotheses are posited:

- (a)

The evolution of the contents evaluated will be associated to specific training, so that an improvement will be observed in the scores of the trained groups, without statistically significant differences found between them. On the other hand, in the quasi-control group, the changes in the scores will be statistically non-significant, as no specific training will be provided during this time. The evolution will not be different as a function of the participant’s university degrees.

- (b)

The groups utilized will show statistically non-significant differences in the initial test (pre-test), while in the other measurements, the experimental groups will obtain better scores than the quasi-experimental group, given the training received. The participant’s degrees will not show differences between them during the three times of measurement.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

The study utilized a quasi-experimental method with a Pre–Post design [

26,

27] with three groups, one of them being the quasi-control group. The design used was complete, as it included all the possible treatment group combinations according to time of observation; likewise, it was not equilibrated, as the number of participants in each experimental group was unequal (

Table 1). As part of the description of the sample’s affiliation variables, the association or relationship of these variables with the treatment groups included in the design will be specified. This is because a statistically significant association or relationship between these variables (not taken into account in the initial analysis model) and the independent variable treatment groups should be considered a potential threat to internal validity. If such an association is found, the inclusion of these variables in the analysis model should be considered.

A total of 143 individuals participated in the study. Fifty-three in-person (37.1%); 47 virtual (32.9%); 43 control (30.1%), with these percentages being statistically similar to each other χ2 (2, N = 143) = 1.063 p = 0.588). Of these, 120 were women and 23 were men. Regarding the total number of participants, there were 44 females and 9 males (83.0% and 17.0%, respectively) in the in-person group, 41 females and 6 males (87.2% and 12.8%, respectively) in the virtual group, and 35 females and 8 males (81.4% and 18.6%, respectively) in the quasi-control group. The possible association between the experimental groups and the sex of the participants was tested in order to rule out, if necessary, sex as a possible rival hypothesis to the experimental one that would explain the results. A χ2 test was used for this purpose, with participants completing all three observations. The value χ2(2, N = 90) = 0.828 is associated with a p = 0.661, so there is nothing to rule out the existence of an association between sex and the experimental groups.

All of them were students enrolled in different degrees at the University of Huelva, with an age range between 19 and 24 years old. The average overall age was 21.54 years, with a standard deviation of 1.751. To contrast the significance of the age differences of the three groups with the objective of discarding this variable as a rival hypothesis, we first tested the adjustment to a normal distribution, using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov Goodness of Fit test for one sample. As can be seen, the age in the virtual group is not distributed following a Normal Law, so the comparison of the age averages between the three groups will be made using the Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric H-test. Contrasting age using the Kruskal–Wallis test between the three groups gives a result of χ2(2; N = 90) = 1.492, with p = 0.474, so there is no argument against stating that the age ranges between the three groups are statistically similar to each other. Therefore, we do not have evidence to suppose that age constitutes a rival hypothesis to the experimental one.

All of them had voluntarily enrolled in the in-person or virtual training programs, or voluntarily participated in the collection of data as a group that did not receive training (quasi-control group). There were no significant differences between the groups that could influence the results.

The requisites for access for each modality were:

In-person: Teaching (all specialties) and Social Education degrees.

Virtual: Psychology, Social Work, Philology, Humanities, and Nursing degrees.

To recruit the quasi-control group, the voluntary collaboration was solicited from a number of classes from the Teaching, Social Education, Psychology, Social Work, Humanities, Philology, and Nursing degrees. The only exclusion criteria were that they would not be able to participate in all three phases of data collection for the study, so that none of the participants was excluded a priori. During the in-person training, attendance was monitored through the signatures of the participants. In virtual training, access to virtual platforms such as Moodle was monitored. In the training program, the following modules were studied:

Module 1: Introduction to Human Sexuality

Module 2. Gender Culture

Module 3. Partner Relationships

Module 4. Basic Prevention Skills

Module 5. Sexuality as an Educational Intervention

2.2. Instrument

A questionnaire was provided, composed by 138 items distributed in the following question blocks:

- 1.

Identity data and background variables

The participants were asked a total of 14 items, which were specifically created for the present study, about affiliation aspects and the possible background variables with respect to those which constituted the nucleus of the research.

- 2.

Knowledge about Sexuality Scale

An abbreviated version of the questionnaire on knowledge about sexuality and sex education [

28] was used. The original instrument is composed of 74 items with a true or false dichotomous response format, as well as an “I don’t know” option to facilitate the response of those who would want to leave an answer blank.

- 3.

Attitudes towards Sexuality Scale

A translated and adapted version of the Kirby Scale created in 1988, on Attitudes towards Sexuality [

2] was used. It is composed of 20 items with Likert-type responses.

- 4.

Attitudes towards Sex Education Scale

The attitudes towards sex education scale is composed of 24 Likert-type items [

29].

- 5.

Global Self-Esteem Scale from Rosenberg

The Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale, created in 1965, is a self-report of 10 items with a Likert-type response scale of five options [

30].

- 6.

Attitudes towards Gender-based violence Scale

This is based on the

Inventory of Beliefs about Wife Beating from Saunders, Lynch, Grayson, and Linz, designed in 1987 [

31]. The original is a questionnaire composed by 3 items with a Likert-type response scale of five options.

- 7.

Attitudes towards Intercultural Sentimental Relationships Scale

This scale was purposely created for the present study. It is composed of 3 Likert-type items.

The dependent variables to for comparisons between groups in the three observations, will be the Knowledge about Sexuality, the Attitudes about Sexuality scale, the Attitude towards Gender-based Violence scale, the Attitudes towards Intercultural Sentimental Relationships scale, and the Rosenberg Global Self-Esteem scale [

30].

Thanks to the study design, we are able to verify the existing differences between the three groups, in general, as the existing difference between the three times of measurement. Likewise, it is possible to verify if the evolution of each group between the three observations is comparable, or on the contrary, if there is a different evolution in one of them or in each of them. Therefore, it can be considered ideal for the empirical verification of the working hypotheses described above.

2.3. Procedure

A week before the start of the in-person and virtual classes, the voluntary collaboration was solicited from individuals enrolled in the degrees in which the training course was offered. The petition for collaboration was made through a message to their institutional emails. The message asked for their collaboration in a study about Sexuality and Sex Education and specified that their participation was completely voluntary and non-paid. They were told that the questionnaire would be available on the first day of class. Likewise, they were reminded that the data obtained would be confidential, with the analysis only to be performed on groups of people and never individually.

The data collection procedure was performed through a standardized online questionnaire. The webpage that hosted the questionnaire was specific for each class, with the creation of a similar page for the quasi-control group participants, except that this page did not include any materials from the class, aside from the questionnaire itself. The webpage was freely available to the participants from the start of data collection in each phase until the end, which was known to them. In every case, the completion date was extended for a week (which this information provided to the participants), to obtain a larger number of completed questionnaires.

A reminder about each data collection event (Pre-Test, Post-Test, and Re-Test) was sent via email, which was sent on the same day to each of the groups. The participants in the virtual group accessed the training program materials between the pre-test and post-test (they did not have access to the re-test), showing a significant increase in knowledge and attitudes in each aspect analyzed.

3. Results

3.1. Evolution of Knowledge about Sexuality

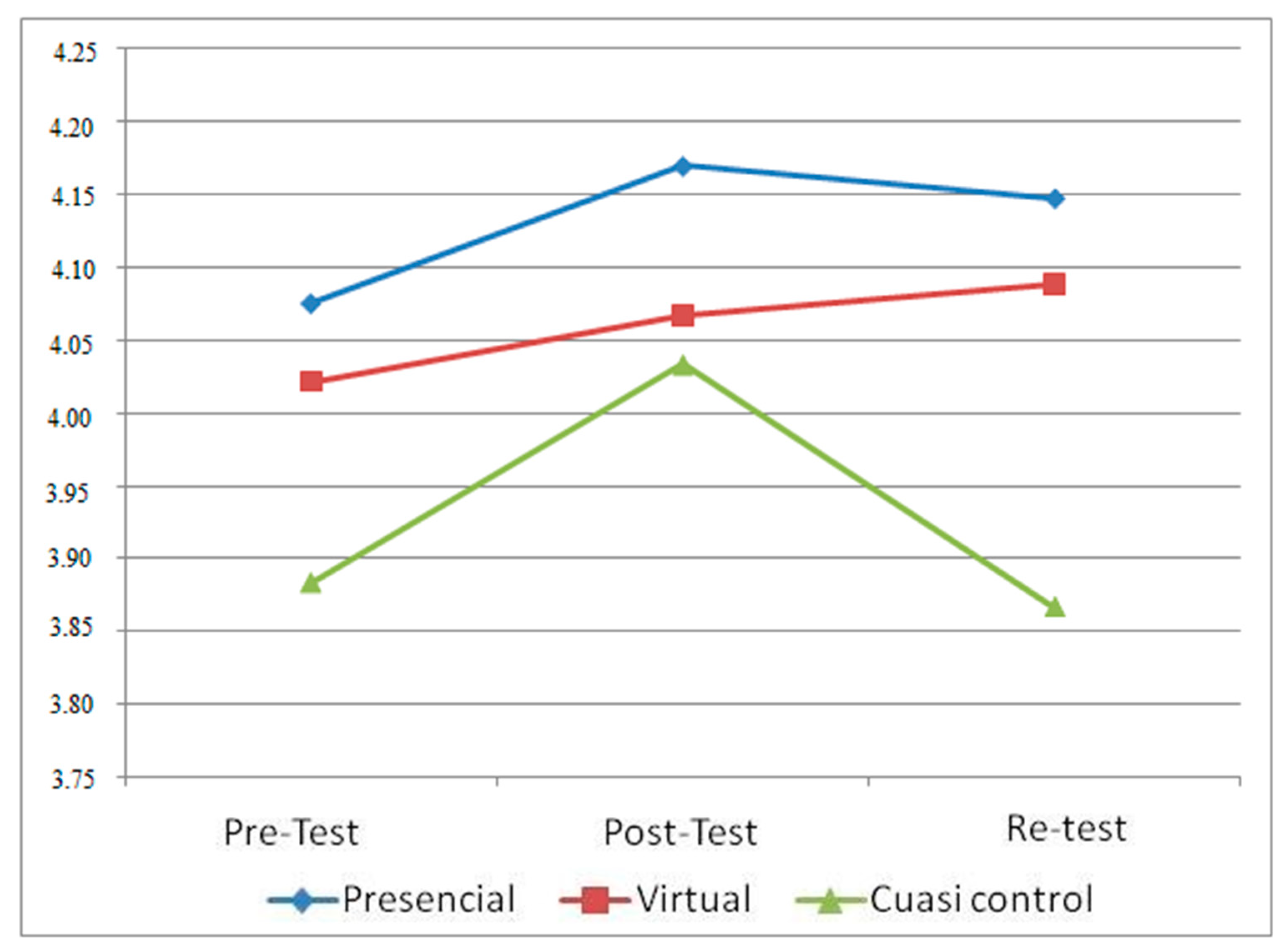

Figure 1 shows the evolution of knowledge about sexuality in the three groups studied (

Figure 1). It is observed that at the start of the course, no significant differences were observed between the three groups, with the mean scores being statistically similar. During the training period, the experimental groups showed an increase in their mean scores, which were statistically significant in the in-person group. Although the differences found in the virtual group were not statistically significant when comparing the scores from the start and end of the training period, it was so when comparing the first measurement with the follow-up one. During these three measurements, the groups that did not receive the training program did not experience any significant improvement on their level of knowledge about sexuality.

In first place, the data were contrasted with a mixed model, repeated-measures ANOVA, with the sum used as the dependent variable. In this model, a systematic variation is defined as that produced by at least one transversal variable that provides inter-subject variation (in this case, the group according to type of training and degree of the participant), and at least one longitudinal variable that provides intra-subject variation (in this case, the different times of measurement), as well as all the effects of interaction between said variables.

Once the compliance of the application requisites had been verified, the ANOVA test was performed. The results showed that the second-order intra-subject interaction effects between Degree x Groups x Time were statistically non-significant (Assumed Sphericity F-value (14, 160) = 1.248, p = 0.2457) as well as the interaction between Degree x Experimental Group (F (2, 80) = 2.507, p = 0.088), and Degree and Measurement Time (Assumed Sphericity F-value (10, 160) = 1.269, p = 0.252), while the effect of Degree was statistically significant (F (5, 80) = 2.884, p = 0.019). Likewise, the effect of interaction of the Groups x Time was statistically significant (Assumed Sphericity F-value (4, 160) = 3.190, p = 0.015) as well as the effect of time of measurement (Assumed Sphericity F-value (2, 160) = 4.574, p = 0.012) and that of Groups (F (2, 80) = 5.132, p = 0.008). Therefore, there is nothing to oppose the analysis of a model without the interaction effects that are statistically non-significant and the making of conclusions about the main effects of the independent variable and the interactions between them.

When analyzing the second model, statistical significance was obtained in the interaction between time of measurement and treatment Group (Assumed Sphericity F-value (4, 164) = 3.819, p = 0.005). This indicates that the conclusions on the main effects, for the time of measurement, as well as the treatment, were not independent between them. That is, the effect provoked by one of the independent variables can vary between the levels of the other independent variable, and vice-versa. Therefore, it is necessary to conditionally analyze this information, to find the nature of the difference between the three observations in each group separately. This can be illustrated through a graphical representation of the estimations of the effects produced by each group in each of the observations (without having in mind the effect produced by the degree of each participant).

3.2. Evolution of the Attitudes towards Sexuality

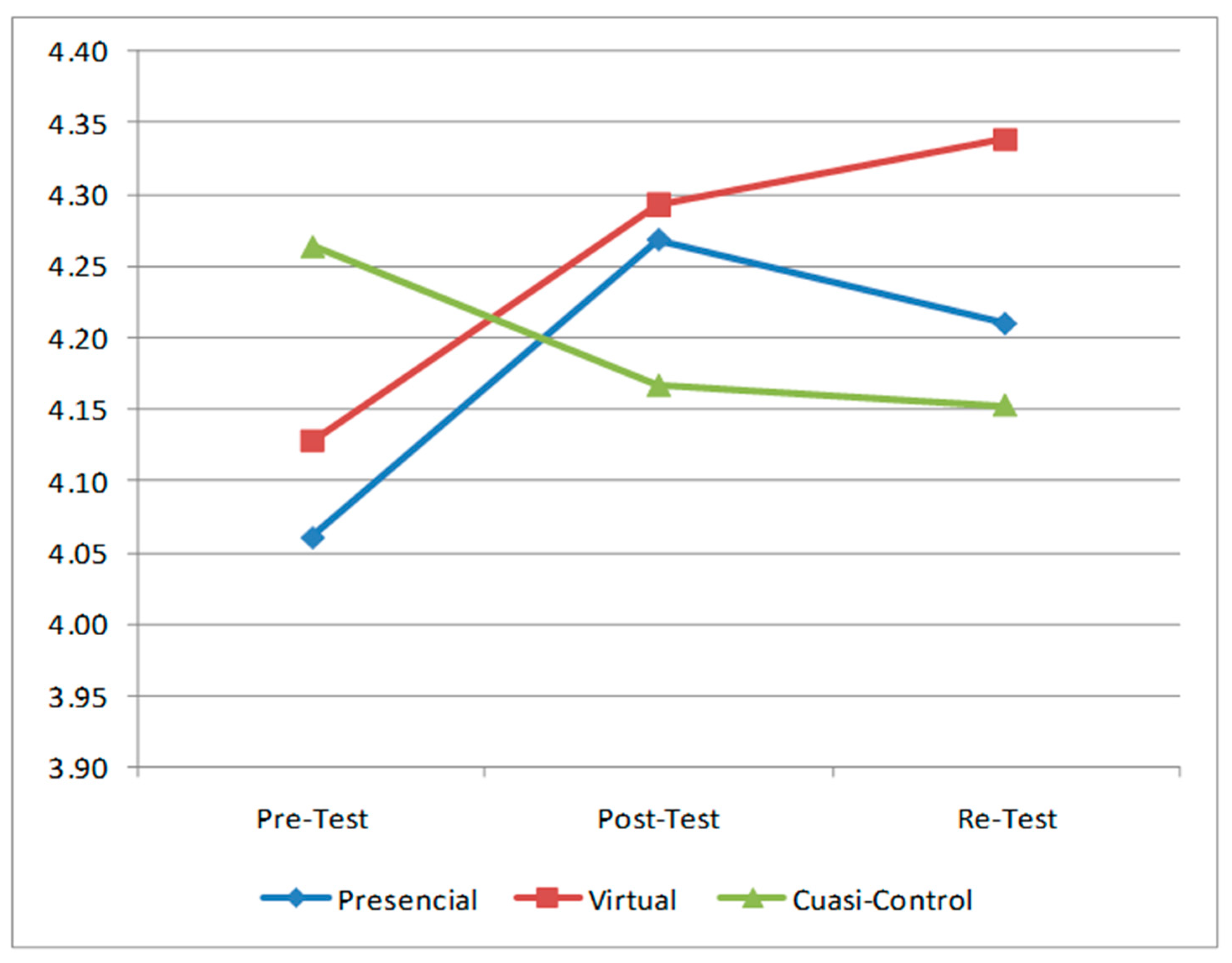

The analysis of the results allows us to state that there is no evidence of a statistically significant change on the attitude towards sexuality associated to the treatment groups (

Figure 2), although a slight improvement was observed in the students enrolled in the Teaching and Philology degrees during the training program.

After the application of the Mixed ANOVA model with the variables treatment Groups and Degree as the transversal variables, and the Time of measurement as the repeated measures variable, non-statistically significant results were found in the interactions between Time x Group (Greenhouse–Geisser F (3.4, 8.5) = 1.086, p = 0.362), Group x Degree (F (1, 72) = 0.195, p = 0.660), and Time, x Group x Degree (Greenhouse–Geisser F (1.7, 122.4) = 3.167, p = 0.054). Likewise, the three main effects were statistically non-significant (Greenhouse–Geisser F for Time (1.7, 122.4) = 0.849, p = 0.430; Group F (2, 72) = 1.001, p = 0.372, and Degree F (5, 72) = 0.880, p = 0.499). However, the effect of the interaction between Time and Degree was statistically significant (Greenhouse–Geisser F (8.5, 122.4) = 2.131, p = 0.035), so that there is statistically different evolution in at least one of the degrees. To find these differences, the simple effects of the repeated measures in each degree were compared, that is the evolution of the Attitude towards Sexuality in each degree was itemized. For this, posterior tests were utilized, with the Bonferroni method of adjustment of the rate of Type I errors. In these tests, two types of statistically significant results were obtained (p < 0.05). On the one hand, the groups of Teaching Degree students (n = 32) increased their mean scores by 0.116 from the Pre-Test to the Post-Test, with this evolution being statistically significant (p = 0.020). On the other hand, the group of participants from the Philology Degree (n = 18) increased their scores by 0.156 points in the same measurements, also indicating a statistically significant improvement (p = 0.016).

3.3. Evolution of the Attitudes towards Sex Education

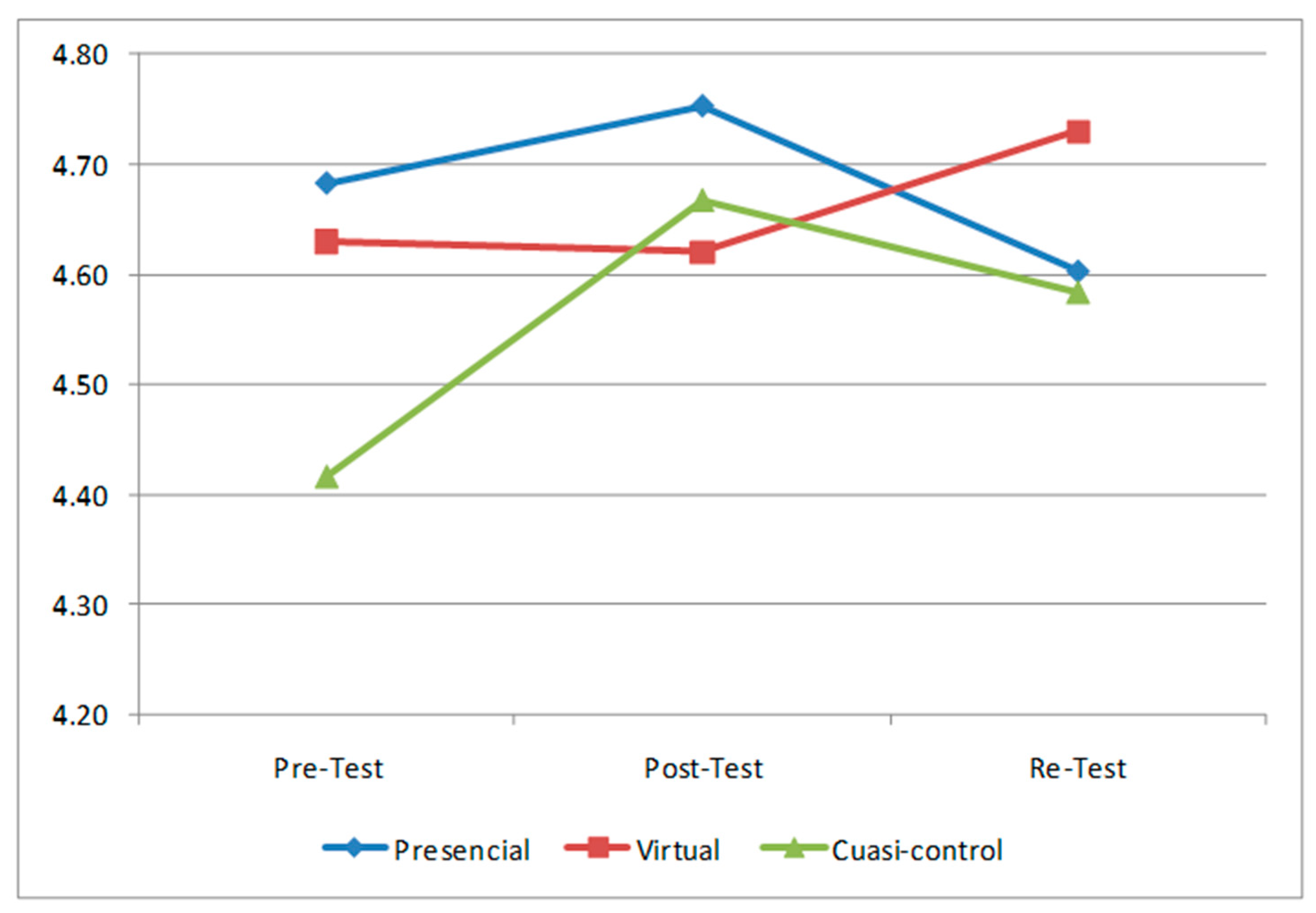

In light of these results, we cannot consider that the attitude towards sex education evolved between the three times of measurement (

Figure 3), and we cannot either count with evidence of differences associated with the Experimental Groups or the participant’s degrees.

For this analysis, two Mixed ANOVA models were applied. In both, the longitudinal variable of repeated measures was the time of measurement; in the first model, the variable Groups was the transversal one, while in the second, the transversal component was the Degree of the participants.

In the Groups variable model, a statistical significance was obtained (p < 0.05) in the main effect of the Time of measurement (Assumed Sphericity F-value (2, 140) = 17.883, p = 0.000), while a lack of statistical significance was found in the main effect of the Groups (F (2, 70) = 0.529, p = 0.592), as well as the interaction effect Groups x Time (Assumed Sphericity F-value (4, 140) = 1.580, p = 0.183). This allows us to conclude that there are differences between the three times of measurement that cannot be explained by the nature of the Treatment Groups, although this statement must be taken with caution, as the quasi-control group was only composed by three participants. To analyze the nature of these differences, a posterior Bonferroni Type I error rate adjustment method was used, with non-statistical results obtained in every case.

Therefore, we cannot verify the existence of differences between the three times of measurement with these data.

As for the model that included the Degree variable, significance was also found in the time of measurement (Assumed Sphericity F-value (2, 134) = 17.644, p = 0.000), while a lack of significance was found in the effect of the Degree (F (5, 67) = 1.273, p = 0.286) and the interaction between them (Assumed Sphericity (10, 134) = 1.036, p = 0.416).

Due to this, there is no evidence of relevant differences between these times of measurement.

3.4. Evolution of the Attitude towards Gender-Based Violence

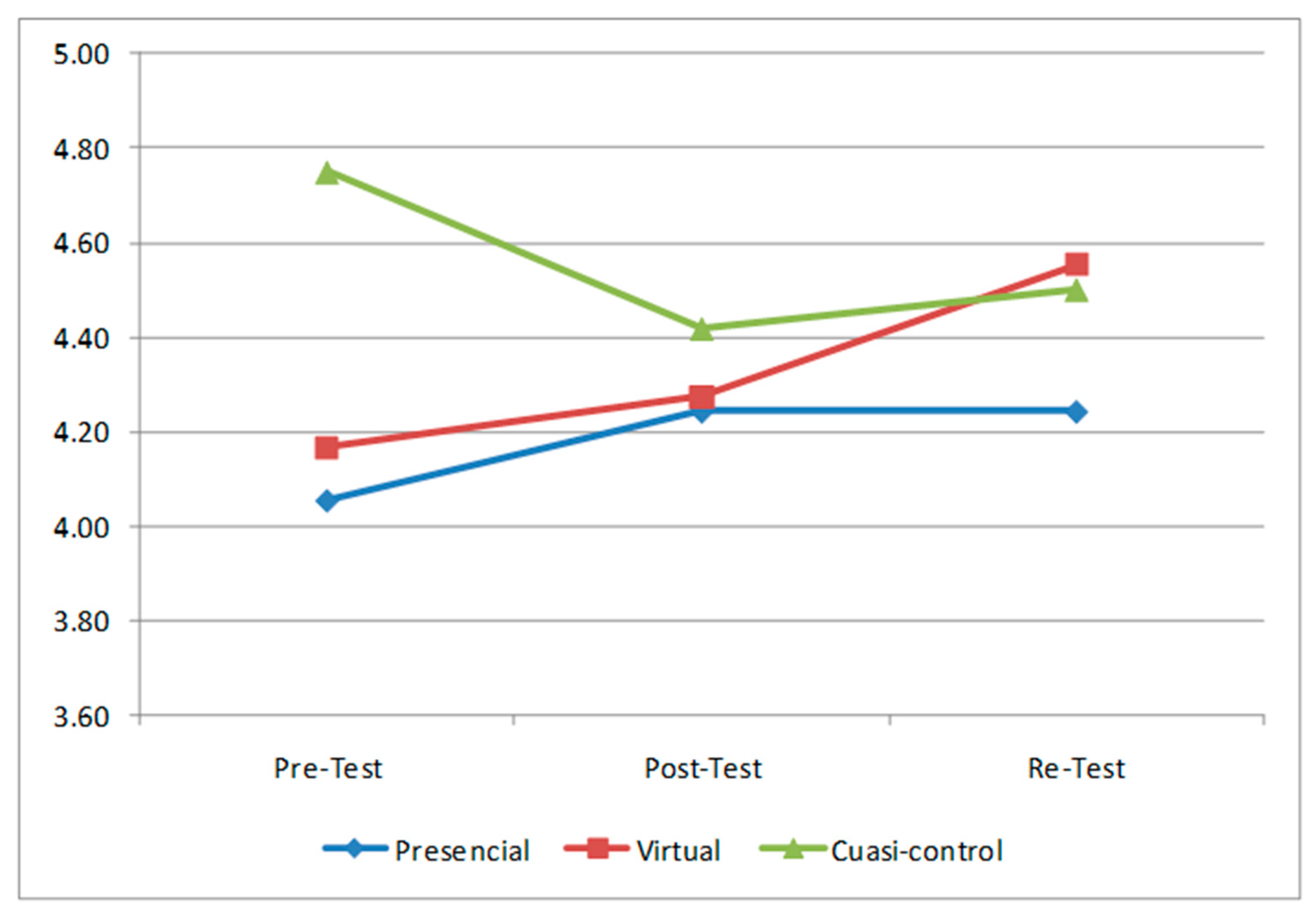

Starting with the previous results, it is concluded that there are no relevant differences between the three groups in any of the times of measurement (

Figure 4), and that, if marginal differences were found in the virtual class group between the three times of measurement, these could be attributed to the greater presence of the participants from the Psychology degree.

The Kruskal–Wallis H-test results show that there were no statistically significant differences in any of the times of measurement.

Likewise, the attitude towards gender violence (AGV) scores for each degree were separately compared. In this case, the non-parametric Friedman’s F test for comparison between related k groups was utilized, conditioning its application to the degree of the participants.

To discover which of these measurements was statistically different from the rest, in the Psychology degree, the differences between the Pre-Test and Post-Test, and the Post-Test and Re-Test were compared with Wilcoxon’s signed-rank T test for matched pairs. A non-statistically significant difference was found between the Pre-Test and Post-Test measurement in the AGV (Z = −0.256,

p = 0.798), although a statistically significant difference was found between the Post-Test and the Re-Test (Z = −2.456,

p = 0.014).

Figure 4 shows the evolution experienced by Psychology students with respect to Attitudes towards Gender-based Violence. The results allow us to conclude that for this degree, a change in the attitude towards gender-based violence was not observed during the course, although an improvement in this attitude was observed after it had ended.

Next, we sought to discover if there were differences between the experimental groups, and if these were statistically significant. Just as with the differences associated with the degree, we verified, in first place, that there were statistically significant differences between the AGV scores of the three groups for each of the times of measurement (transversal differences between the groups), and in second place, we verified the evolution of each of the groups (longitudinal differences within each group).

As for the transversal differences, Kruskal–Wallis H test was applied. Statistically significant differences were not found between the three groups with respect to Attitude towards Gender-based Violence (p > 0.05) in none of the three times of measurement. Therefore, it can be concluded that the scores found in the Attitude towards Gender-based Violence were independent from the experimental groups at each time of measurement.

For the longitudinal tests, the Friedman F test for k related groups was utilized, conditioned to the experimental groups. The differences obtained were statistically non-significant in every case (p < 0.95). In the case of the virtual group, marginally significant differences were obtained, with this group containing the largest number of participants enrolled in the Psychology degree (in total, 13 out of 14 who completed the three measurements).

3.5. Evolution of the Attitude towards Intercultural Sentimental Relationships

In light of these results, it can be concluded that with respect to the attitude towards sentimental relationships between individuals of different race, ethnicity, or culture, the participants did not show differences between them due to their belonging to one or another experimental group (

Figure 5) or their different degrees. The evolution of the score was only statistically significant in the case of the Philology degree, being non-significant in the different experimental groups, as well as the rest of the degrees.

The model applied was Mixed or Partially Repeated Measures, considering two transversal variables (experimental groups and participant’s degrees), and a longitudinal one (time of measurements or time).

Once the application requisites were verified, a non-statistically significant result was obtained in the second-order interaction Measurements x Groups x Degree (Assumed Sphericity F-value (4, 154) = 1.864, p = 0.120), so that the results obtained from the first-order interactions can be interpreted. Among them, those that involved the experimental groups were not statistically significant (Assumed Sphericity F-value for Measurement x Groups (4, 154) = 1.187, p = 0.319; Group x Degree F-value (2, 77) = 2.471, p = 0.091), so a conclusion can be made about the main effect of the groups in an unconditioned manner. This main effect was, likewise, statistically non-significant (Groups F (2, 77) = 1.562, p = 0.216), so that differences do not exist in the attitude towards the inter-ethnic sentimental relationships associated to the treatment groups.

On the other hand, the interaction Measurement x Degree was statistically significant (Assumed Sphericity F-value (10, 154) = 2.220, p = 0.019), which indicates that the conclusions on the degree are conditioned to the time of measurement and vice-versa, that is, there is an evolution in the different score in at least one of the degrees. To examine how the score from the scale evolved in the different degrees, a posterior pair-wise comparison test was applied with the Bonferroni correction. In first place, the difference between the different degrees in each of the measurements was compared separately, with non-statistically significant results obtained in every case, as the absolute differences between the degrees oscillated between 0.00 in the least of the cases, and 2.14 in the most disparate result. Posteriorly, the difference between the different measurements in each of the degrees was verified, obtaining a statistically significant result only in the comparison between the Pre-Test and the Re-Test of the Philology degree (significance = 0.003), with a difference of 1.40 points (with a standard error of 0.409) for its highest score in the Re-Test.

3.6. Evolution of Self-Esteem

Given these results, there is no statistically significant evidence that points to the existence of an effect of the Training Groups on Self-Esteem. Likewise, it cannot be stated that this score evolved with time. Lastly, the participants from the different degrees showed self-esteem results that did not statistically significantly differ between them.

When interpreting the scores of the participants from a Mixed ANOVA Method (using a Type IV sums of squares), with the Training Group as the inter-subject variable (with an Independent Variable status), and the Degree (with a status of statistically-controlled nested Extraneous Variable) as the inter-subject variables, and with the intra-subject variable being the three times measurement, it was found that none of the main effects of these variables, just as with all the first- and second-order interactions possible, were statistically significant (p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

Due to the characteristics of the study, the joint influence of the degree of the participants and the treatment groups considered (three in total: two experimental—in-person training and virtual training—and one quasi-control) was analyzed. It is important to remember that the hypothesis testing method minimizes the influence of the perturbing variable from the interpretative model. In this way, the conclusions made on the training process are independent from the influence of the degree.

The general hypothesis deals with the evolution of the scores, with the idea that it will be influenced by the training received on sexuality, and not due to the initial degree of the individuals. Favorable evidence was obtained that allows the maintenance of this hypothesis in the case of the variable Knowledge about Sexuality, while in the rest of the variables, the evidence obtained was unfavorable to its relevance. Likewise, the second general hypothesis, on the transversal differences in each of the times of measurement, favorable evidence was found in the case of the variable Knowledge about Sexuality, with unfavorable evidence found for the rest of the concepts measured, which are analyzed next.

Statistically significant evidence was found on an improvement on Knowledge about Sexuality of the participants who were part of either of the experimental groups, that is, those who followed the training process. Before the training period, these groups had a similar knowledge about sexuality, which was also statistically similar to the group that did not receive this training. However, during the training period, the in-person group, as well as the virtual one, increased their knowledge, with this increase significantly relevant in the in-person group, although slightly relevant in the virtual group. At the end of the course, the increase led to a significant distancing between the individuals in the in-person group, as compared to those who did not take the course, with this difference also evident in the follow-up measurement in the participants who enrolled in the virtual modality. In this period, the participants in the group that did not receive training did not improve their knowledge. As for the level of knowledge, important differences were not found between the participants from the different degrees. This finding (the lack of an important influence between the degree and the absence of a significant evolution in the quasi-control group) allows us to discard rival hypotheses such as the influence of sources that were not considered in the study, to which the sample may have been exposed to. Likewise, the influence of other courses in the improvement of the knowledge of the participants is discarded.

The question arises about the reason why the virtual group did not obtain a statistically significant difference between the start and end of the course, as observed in the control group. It is possible that this could be due to the special characteristics of virtual training, where the participant can choose when to access the course contents, which were available during the rest of the academic year.

As for the attitudes, both towards sexuality as well as sex education, a statistically significant difference was not found on the attitude towards sexuality due to the treatment, although the Teaching and Philology degree participants experienced a slight improvement during the course in their attitude towards sexuality. To interpret these results, it should be considered that the participants were volunteers who freely chose to learn about sexuality and sex education, so that the high initial level of a favorable attitude towards them can provoke the ceiling effect. This is shown by the means obtained in the Pre-Test in the attitude towards sexuality scale (4.1 in the In-person group, 4.0 in the Virtual group, and 3.9 in the Quasi-control group), attitude towards sex education (4.1 in the In-person and Virtual groups, and 4.3 in the Quasi-control group), attitude towards gender-based violence (4.7 in the In-person group, 4.6 in the Virtual group, and 4.4 in the Quasi-control group), and attitude towards inter-ethnic sentimental relationships (4.1 in the In-person group, 4.2 in the Virtual group, and 4.8 in the Quasi-control group). These high and statistically similar values in all the groups and measurements indicate the existence of this effect: especially high measurements were obtained in variables that should have increased with the treatment, a phenomenon that results in the treatment apparently being inefficient. It would be necessary to discover the effectiveness of the education programs in the change in the attitudes in individuals who are not initially motivated towards the subject matter or define another research method for their comparison (for example, a prospective Ex Post Facto regression discontinuity design between groups that have extreme attitudes). For this reason, it is advisable to not interpret the results obtained in these measurements, given that a Type II error could be made, by considering the treatment inefficient when it fact, it is.

In general, attitudes tend to be temporarily stable through a person’s life, so that change is not always fast [

2,

23,

32]. Due to this, there tends to be a stable global attitude pattern towards sexuality. According to these authors, the inclusion of attitudes as content in Sex Education requires their knowledge, analysis, and evaluation, with diverse techniques, as a function of the objectives of the pedagogic intervention. Along with questionnaires, the usefulness of interviews, discussion groups, behavioral assays, and body-based techniques are underlined, among others.

The results shown are similar to those from other studies conducted, because they broadly show a significant increase in the variable

knowledge of the groups who received training, and a lower or null increase, in the variable

attitude [

3,

4,

12,

33]. These analyses are similar to the methodological design of the present study, as they were quasi-experimental studies that included control and experimental groups, with a pre and post design, and with a training program. However, the duration of the programs in all the cases was very superior to that planned in the present study and focused on adolescents enrolled in Secondary Education [

4]. The results of these studies, along with those presented herein, can be explained by the temporal stability of the attitudes alluded to in other studies [

2,

12]

Additionally, it is necessary to urge the education policy makers to consider sex and affective education in a manner that is intrinsic to the comprehensive training of individuals and with sufficient gravity for its incorporation into the curriculum from the early childhood stage to university studies.

The study has many limitations that are intrinsic to quasi-experimental studies, that is, the application of the experimental method to natural or applied contexts, which coincide with other studies along the same line [

6,

7,

8,

34,

35,

36]. In first place, the quasi-experimental method in itself lacks the possibility of a control element found in experiments conducted in the laboratory [

7]. In the case of the present study, the dependent variable was human sexuality, analyzed from the point of view of knowledge about it, the attitudes and education towards it, the attitudes towards gender-based violence and inter-ethnic relationships, and self-esteem. If we consider the multiplicity of variables that could have had an influence on these dimensions, it is simply observed that it is not possible to isolate human beings from this influence during the duration of the course proposed. Therefore, it must be assumed that part of the evolution found could be due to influences that were controlled for in the present study, such as lectures, audiovisual material, influence of other courses, influence of peers or partner, sexual encounters experienced during the course, etcetera.

A normal limitation in the application of the research model applied to natural contexts is the use of samples that were selected in a non-probabilistic manner. In this case, all the participants voluntarily attended due to unknown processes. This sample selection procedure answers to criteria of suitability and accessibility inherent to itself, not criteria of generalization of results to a previously defined population. Thus, the results must not be generalized to the whole set of individuals enrolled in these university degrees, as they cannot be extended beyond the individuals who took part in the study.

Another limitation, inherent to the specification of the scheme of the quasi-experimental study, was the association between the degrees and treatment groups. The institution solicited the non-offering of different elective courses to the same degree, so that the division between the in-person and virtual groups was associated to the corresponding degrees. This association makes difficult the process of inference, which could cause an internal validity problem if it is not considered or is unknown. In the present study, it was taken into account by including the degree in the model, and by obtaining indicators that were independent from each other with respect to the variation produced by the degree and the experimental groups, thanks to the calculation of the Type IV sums of squares. As statistical significance was obtained in the association of knowledge with both treatment groups and degree, an ideal design should have included an orthogonal combination (that is, independent) of both variables, to be able to completely study the interactive effect of both variables, as well as their main effects.

On the other hand, an excessive experimental mortality was detected, associated to the quasi-control group and the Psychology degree. Although the group participated voluntarily, it did so due to the enrolment in elective courses necessary for finishing the degree. It must be considered that the Psychology degree, likewise, was statistically significantly associated to the participation in the quasi-control group, so that it is not possible to conclude, in a manner that is valid, if the abandonment was due to the characteristics of the quasi-control group or the participants enrolled in this degree. In any case, no evidence was found of an association between the degree and any other characteristic. With respect to abandonment, it was possibly due to the loss of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation of the quasi-control group. Thus, in future studies, a suggestion is made to plan for some type of comparison with this variable, for example, the participation of individuals who are motivated towards this subject matter.