Adapting Open Innovation Practices for the Creation of a Traceability System in a Meat-Producing Industry in Northwest Greece

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Traceability

1.2. Current Status of Pork Production in Greece

- The per capita consumption of pork has remained stable at 27.2 kg/person in recent years;

- Poultry meat follows, with an annual per capita consumption of 26.9 kg/person in 2017;

- Beef/veal (15.4 kg/person);

- Sheep and goat meat (6.8 kg/person).

1.3. Open Innovation

1.4. Aim of the Investigation

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Methodology

2.2. General Information

3. Results

3.1. Profile of the Sample

3.2. Correlation between Socio-Economic Profile and Preference for Traceable Pork

- The sex of the participants did not have any bearing on pork consumption (p-value = 0.640 at a significance level of 5% (but also at 1% and 10%)), meaning that both sexes choose to buy traced pork with equal probability, i.e., the variables are unrelated to each other.

- The age of the participants also did not have any bearing on pork consumption. (p-value = 0.381 at a significance level of 5% and 10%). Therefore, the probability of buying traced pork by age group is the same, i.e., the variables are not correlated. This result is to be expected, as pork is a food that is enjoyable for all ages.

- The same goes for marital status. The chi-square test shows that statistically there is no significant difference between the marital status of the respondents (p-value = 0.951) at the significance level of 1%, 5%, and 10%. Consequently, the probability of buying traced pork does not depend on marital status, i.e., the variables to be examined are not related to each other.

- Monthly income was also examined. The chi-square test showed no correlation between income and the probability of buying traced pork (p-value = 0.765) at a significance level of 5% (and at 1% and 10%).

- Education was also irrelevant concerning whether or not to buy traced pork (p-value = 0.665 at a significance level of 1%, 5%, and 10%.)

3.3. Traceability and Consumers

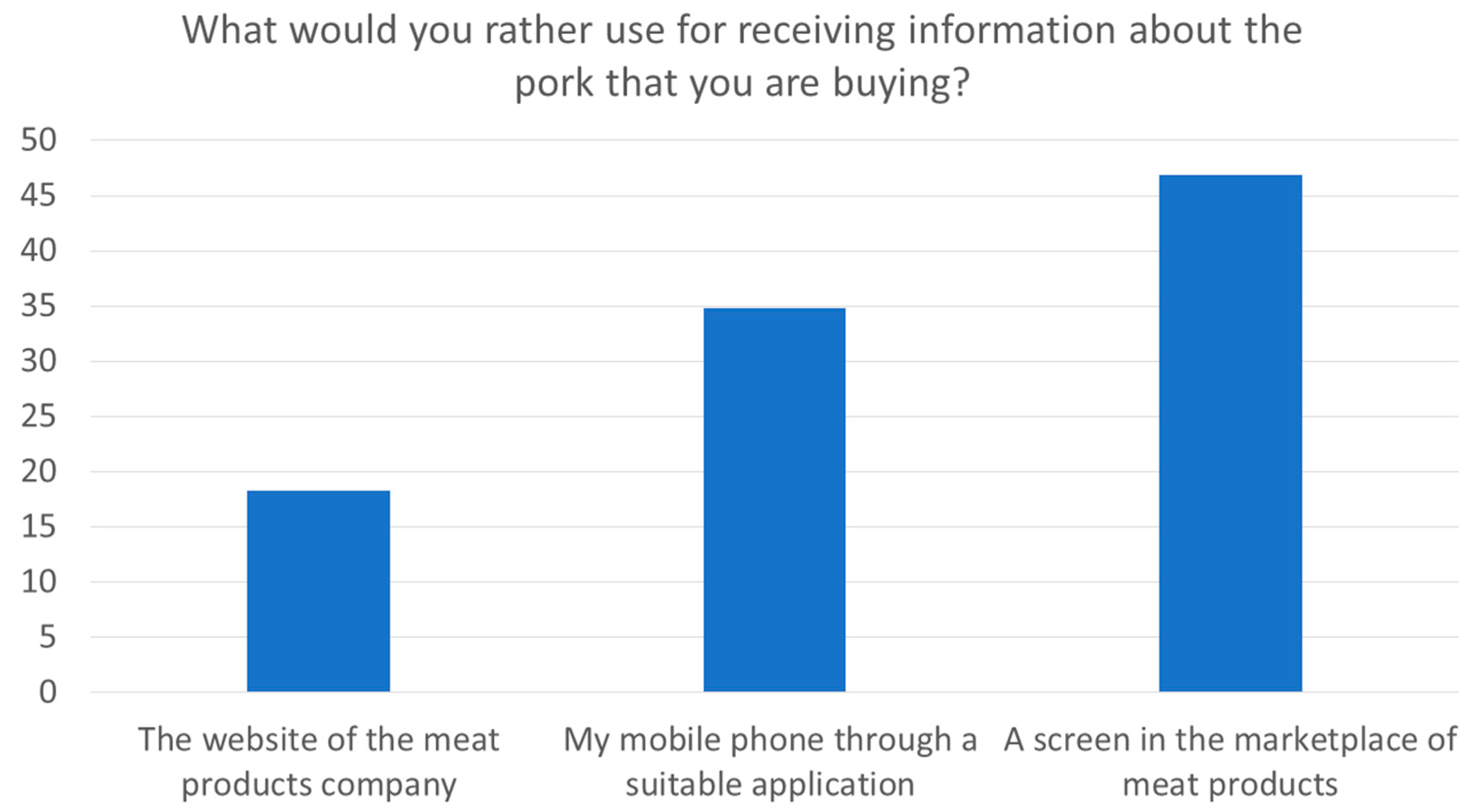

3.4. Methods of Receiving Information

3.5. SMEs and Traceability

- The use of a code to identify each pork product or with the use of a batch number for all the animals;

- The health of the animal and the hygiene of the carcass, which is ensured by the necessary veterinary checks, under the responsibility of both the appropriate health authorities and as well as the company;

- The breeding of the animal with nutritious and safe feeds;

- The yield of useful meat by measuring the initial weight of the animal, the breeding time, the weight before slaughter, and the weight of the useful meat;

- The storage conditions of the meat products before they are sent to the retailers and the date they received them;

- The expiration date indicated on the packaged products is data that certifies that the distributed products are safe for consumption.

- Standardizing procedures and having more effective overseeing of the overall process.

- More effective monitoring will help in troubleshooting and lead to immediate problem management, minimizing the number of errors associated with all stages of production. This also minimizes the creation of problematic and /or unsafe batches and makes them more easily identified and withdrawn.

- Livestock management will also be more effective, leading to a higher meat yield, resulting in increased productivity.

4. Discussion

Analysis of the Results of the Market Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pei, X.; Tandon, A.; Alldrick, A.; Giorgi, L.; Huang, W.; Yang, R. The China melamine milk scandal and its implications for food safety regulation. Food Policy 2011, 36, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Tacken, G.M.L.; Liu, Y.; Sijtsema, S.J. Consumer trust in the dairy value chain in China: The role of trustworthiness, the melamine scandal, and the media. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 8554–8567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visciano, P.; Schirone, M. Food frauds: Global incidents and misleading situations. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 424–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO Codex Alimentarius. Principles for traceability/product tracing as a tool within a food inspection and certification system. Cac/Gl 2018, 1, 1–423. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, S.; Cullen, J.M. Food traceability: A generic theoretical framework. Food Control. 2021, 123, 107848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, V.; Margariti, S.V.; Salmas, D.; Stylios, C.; Kafetzopoulos, D.; Skalkos, D. Design and develop cloud-based system for meat traceability. CEUR Workshop Proc. 2020, 2761, 475–484. [Google Scholar]

- Galimberti, A.; Casiraghi, M.; Bruni, I.; Guzzetti, L.; Cortis, P.; Berterame, N.M.; Labra, M. From DNA barcoding to personalized nutrition: The evolution of food traceability. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2019, 28, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espiñeira, M.; Santaclara, F.J. What Is Food Traceability? Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; ISBN 978-0-08-100321-3. [Google Scholar]

- Curto, J.P.; Gaspar, P.D. Traceability in food supply chains: Review and SME focused analysis—Part 1. AIMS Agric. Food 2021, 6, 679–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Ruiz-Garcia, L.; Fan, B.; Robla Villalba, J.I.; McCarthy, U.; Zhang, B.; Yu, Q.; Wu, W. Food traceability system from governmental, corporate, and consumer perspectives in the European Union and China: A comparative review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 99, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalkos, D.; Kosma, I.S.; Vasiliou, A.; Guine, R.P.F. Consumers’ trust in greek traditional foods in the post covid-19 era. Sustainubility 2021, 13, 9975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.; Giannetto, M.; Careri, M. Analytical systems and metrological traceability of measurement data in food control assessment. TrAC-Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 107, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadood, S.A.; Boli, G.; Xiaowen, Z.; Hussain, I.; Yimin, W. Recent development in the application of analytical techniques for the traceability and authenticity of food of plant origin. Microchem. J. 2020, 152, 104295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVey, C.; Elliott, C.T.; Cannavan, A.; Kelly, S.D.; Petchkongkaew, A.; Haughey, S.A. Portable spectroscopy for high throughput food authenticity screening: Advancements in technology and integration into digital traceability systems. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Wang, H.; Wei, M.; Lan, T.; Wang, J.; Bao, S.; Ge, Q.; Fang, Y.; Sun, X. Application of smart-phone use in rapid food detection, food traceability systems, and personalized diet guidance, making our diet more health. Food Res. Int. 2022, 152, 110918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimy, L.; Treiblmaier, H.; Jain, G. Distributed ledger technology as a catalyst for open innovation adoption among small and medium-sized enterprises. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2021, 32, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftekhar, A.; Cui, X. Blockchain-based traceability system that ensures food safety measures to protect consumer safety and COVID-19 free supply chains. Foods 2021, 10, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Wang, X.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X. Applying blockchain technology to improve agri-food traceability: A review of development methods, benefits and challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvez, J.F.; Mejuto, J.C.; Simal-Gandara, J. Future challenges on the use of blockchain for food traceability analysis. TrAC-Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 107, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, S.; May, D.; Leontidis, G.; Swainson, M.; Brewer, S.; Bidaut, L.; Frey, J.G.; Parr, G.; Maull, R.; Zisman, A. Are Distributed Ledger Technologies the panacea for food traceability? Glob. Food Sec. 2019, 20, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creydt, M.; Fischer, M. Blockchain and more—Algorithm driven food traceability. Food Control. 2019, 105, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafetzopoulos, D.; Stylios, C.; Skalkos, D. Managing traceability in the meat processing industry: Principles, guidelines and technologies. CEUR Workshop Proc. 2020, 2761, 302–308. [Google Scholar]

- Haleem, A.; Khan, S.; Khan, M.I. Traceability implementation in food supply chain: A grey-DEMATEL approach. Inf. Process. Agric. 2019, 6, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICAP CRIF Business Information Services|ICAP CRIF in Greece MEAT; ICAP CRIF: Athens, Greece, 2018.

- Gamage, S.K.N.; Ekanayake, E.M.S.; Abeyrathne, G.A.K.N.J.; Prasanna, R.P.I.R.; Jayasundara, J.M.S.B.; Rajapakshe, P.S.K. A review of global challenges and survival strategies of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Economies 2020, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W. Open innovation. In The Routledge Companion to Innovation Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; p. 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, T.Y.; Fisher, G.J.; Qualls, W.J. The effects of inbound open innovation, outbound open innovation, and team role diversity on open source software project performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 94, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lancker, J.; Wauters, E.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. Open innovation in public research institutes -success and influencing factors. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 23, 1950064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Chesbrough, H. Measuring open innovation practices through topic modelling: Revisiting their impact on firm financial performance. Technovation 2021, 102434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglietta, N.; Battisti, E.; Campanella, F. Value maximization and open innovation in food and beverage industry: Evidence from US market. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 2477–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe-Echeberria, R.; Igartua, J.I.; Lizarralde, R. Implementing open innovation in research and technology organisations: Approaches and impact. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2019, 5, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bertello, A.; Ferraris, A.; De Bernardi, P.; Bertoldi, B. Challenges to open innovation in traditional SMEs: An analysis of pre-competitive projects in university-industry-government collaboration. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2022, 18, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.A.; Sánchez-Cubo, F.; Mondéjar-Jiménez, J. Consumer Behaviour towards Pork Meat Products: A Literature Review and Data Analysis. Foods 2022, 11, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Groups | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 25 |

| Female | 75 | |

| Age | 18–30 | 17 |

| 31–45 | 21.4 | |

| 46–55 | 42 | |

| >55 | 19.6 | |

| Educational level | High school | 34.8 |

| University | 58.9 | |

| Postgraduate | 6.3 | |

| Personal monthly income EUR | <500 | 9.8 |

| 500–1000 | 29.9 | |

| 1000–1500 | 25.9 | |

| 1500–2000 | 18.8 | |

| >2000 | 15.6 | |

| Marital status | Single | 17.4 |

| Married | 75.9 | |

| Divorced | 4.9 | |

| Widowed | 1.8 | |

| Pork consumption frequency | twice a week | 18.8 |

| once a week | 68.3 | |

| once or twice a month | 12.9 |

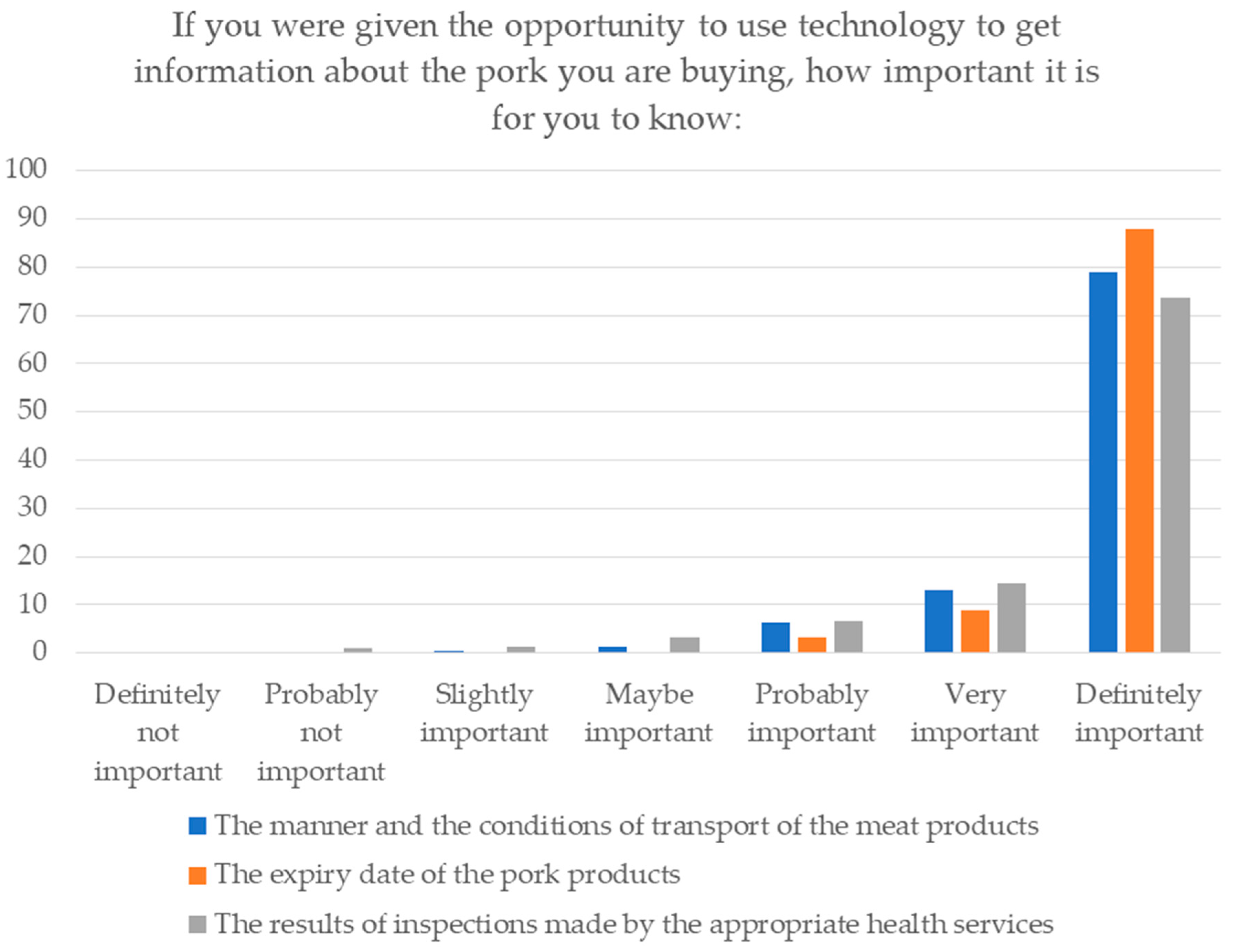

| If You Were Given the Opportunity to Use Technology to Get Information about the Pork You Are Buying, How Important Is It for You to Know: | Definitely Not Important | Probably Not Important | Slightly Important | Maybe Important | Probably Important | Very Important | Definitely Important |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 1. The country of origin | 3.6 | 7.1 | 7.6 | 12.5 | 14.7 | 22.8 | 31.7 |

| 2. The name of the pork-producing unit | 4 | 9.4 | 10.3 | 15.2 | 16.5 | 21.4 | 23.2 |

| 3. Information about raising the animal e.g., type of feed, rearing method (free-range, organic) | 0.9 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 4.9 | 33.9 | 54.9 |

| 4. Information about the hygiene and health of the animal before slaughter e.g., animal husbandry conditions, administration of antibiotics or other drugs | 0 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 4.9 | 29.9 | 63.4 |

| 5. The country and date of slaughter | 0 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 11.2 | 34.4 | 49.1 |

| 6. The age of the animal at slaughter | 0.4 | 2.7 | 6.7 | 13.8 | 20.1 | 29 | 27.2 |

| 7. The date of processing of the carcass | 3.1 | 8 | 10.3 | 17 | 20.1 | 22.8 | 18.8 |

| 8. The results of chemical and/or microbiological tests | 1.8 | 3.1 | 5.4 | 9.8 | 15.2 | 15.6 | 49.1 |

| 9. The place and storage conditions of meat products | 0 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 9.8 | 15.6 | 70.5 |

| 10. The manner and the conditions of transport of the meat products | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 6.3 | 12.9 | 79 |

| 11. The date the meat products were received by the final retailer e.g., supermarket, butcher | 0 | 0.9 | 4 | 8.5 | 15.6 | 23.7 | 47.3 |

| 12. Freezing date and freezing conditions of frozen pork products | 0.9 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 4.9 | 11.6 | 16.1 | 63.4 |

| 13. The date and conditions of packaging of fresh pork products | 1.3 | 2.7 | 4.9 | 8.5 | 13.4 | 15.6 | 53.6 |

| 14. The expiry date of the pork products | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.1 | 8.9 | 87.9 |

| 15. The results of inspections made by the appropriate health services | 0 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 3.1 | 6.7 | 14.3 | 73.7 |

| 16. Information on the implementation of food safety and hygiene system (ISO 22001 or quality (ISO 9001) | 1.3 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 8 | 12.9 | 16.1 | 54.5 |

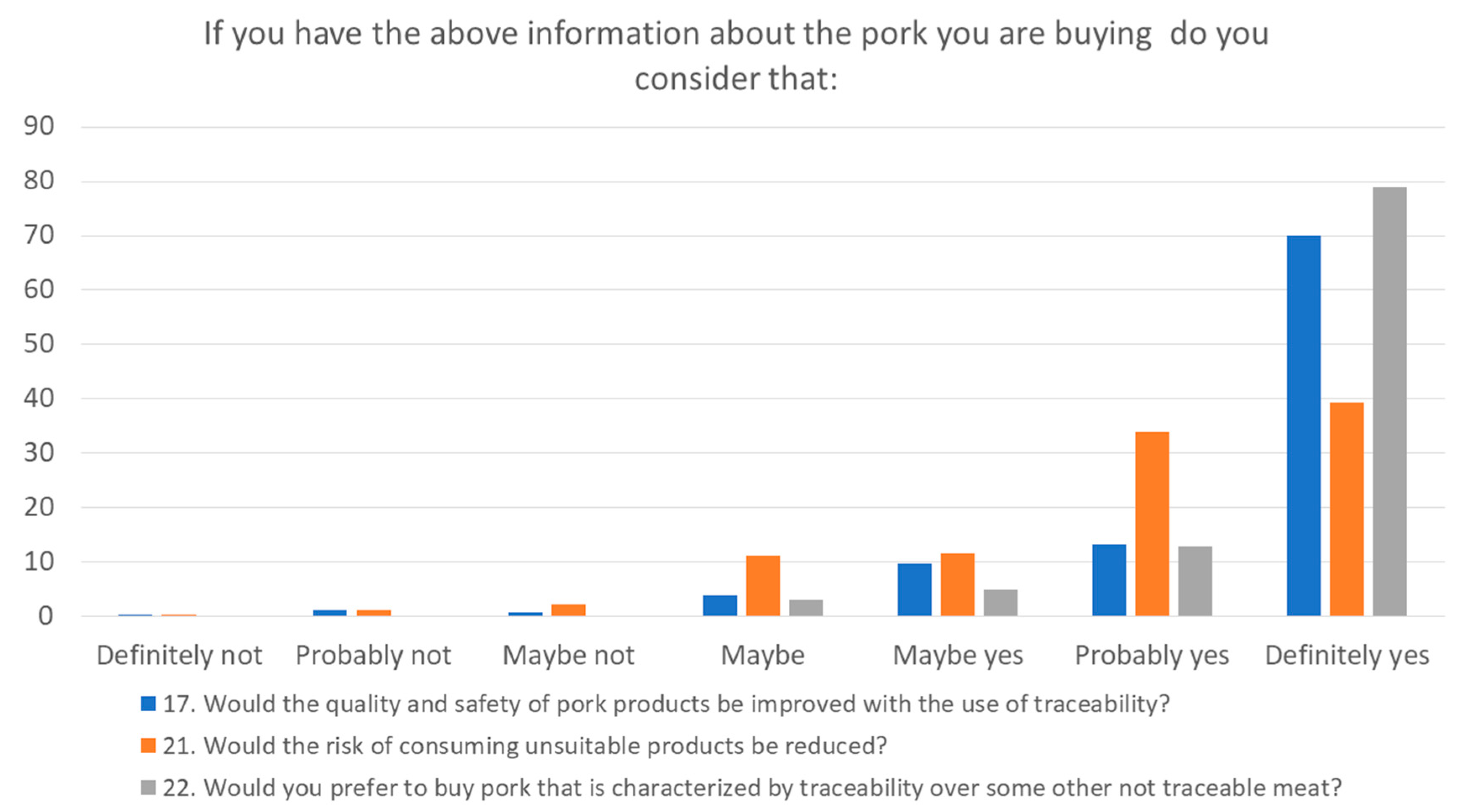

| If You Have the above Information about the Pork You Are Buying, Do You Consider That: | Definitely Not | Probably Not | Maybe Not | Maybe | Maybe Yes | Probably Yes | Definitely Yes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| 17. Would the quality and safety of pork products be improved with the use of traceability? | 0.4 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 4 | 9.8 | 13.4 | 70.1 |

| 18. Would your confidence in the hygiene and safety of pork products increase? | 0 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 8 | 15.6 | 32.1 | 40.2 |

| 19. Would public health be more effectively protected? | 0 | 0.4 | 2.2 | 5.8 | 21 | 37.5 | 33 |

| 20. Could you make a better quality–price comparison? | 0 | 3.1 | 3.6 | 7.1 | 18.3 | 33.5 | 34.4 |

| 21. Would the risk of consuming unsuitable products be reduced? | 0.4 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 11.2 | 11.6 | 33.9 | 39.3 |

| 22. Would you prefer to buy pork characterized by traceability over some other not-traceable meat? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.1 | 4.9 | 12.9 | 79 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dima, A.; Arvaniti, E.; Stylios, C.; Kafetzopoulos, D.; Skalkos, D. Adapting Open Innovation Practices for the Creation of a Traceability System in a Meat-Producing Industry in Northwest Greece. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5111. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095111

Dima A, Arvaniti E, Stylios C, Kafetzopoulos D, Skalkos D. Adapting Open Innovation Practices for the Creation of a Traceability System in a Meat-Producing Industry in Northwest Greece. Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):5111. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095111

Chicago/Turabian StyleDima, Agapi, Eleni Arvaniti, Chrysostomos Stylios, Dimitrios Kafetzopoulos, and Dimitris Skalkos. 2022. "Adapting Open Innovation Practices for the Creation of a Traceability System in a Meat-Producing Industry in Northwest Greece" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 5111. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095111

APA StyleDima, A., Arvaniti, E., Stylios, C., Kafetzopoulos, D., & Skalkos, D. (2022). Adapting Open Innovation Practices for the Creation of a Traceability System in a Meat-Producing Industry in Northwest Greece. Sustainability, 14(9), 5111. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095111