How Do Different Types of University Academics Perceive Work from Home Amidst COVID-19 and Beyond?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

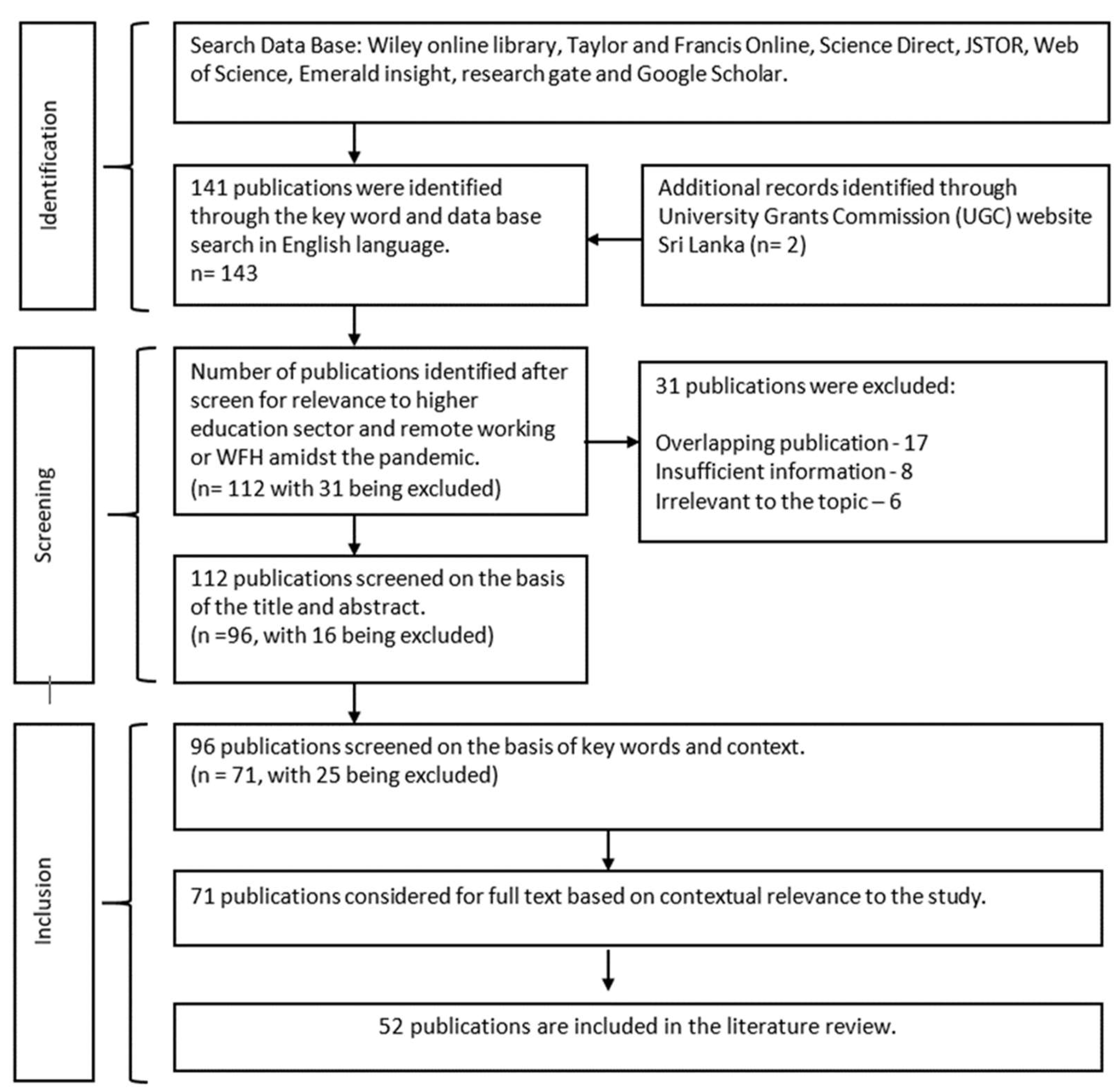

3. Methodology

Analytical Framework

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Reliability Results

4.3. Baseline Regression Results and Robustness Checks

5. Discussion

6. Implications and Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Demographics | Categories | N | Percentage (%) |

| Age | 25–30 Years | 64 | 18.99 |

| 31–35 Years | 56 | 16.62 | |

| 36–40 Years | 37 | 10.98 | |

| 41–45 Years | 62 | 18.40 | |

| 46–50 Years | 45 | 13.35 | |

| 51–55 Years | 43 | 12.76 | |

| 56 and above years | 30 | 8.90 | |

| Gender | Male | 165 | 48.96 |

| Female | 172 | 51.04 | |

| Highest Educational Qualification | Bachelors | 34 | 10.09 |

| Masters | 105 | 31.16 | |

| MPhil | 17 | 5.04 | |

| PhD | 175 | 51.93 | |

| DSC | 6 | 1.75 | |

| Experience as an academic | 0–5 Years | 99 | 29.38 |

| 6–10 Years | 58 | 17.21 | |

| 11–15 Years | 41 | 12.17 | |

| 16–20 Years | 60 | 17.80 | |

| 21–25 Years | 52 | 15.43 | |

| 26–30 Years | 7 | 2.08 | |

| 31 and above years | 20 | 5.93 | |

| University Sector | Public | 281 | 83.38 |

| Private | 56 | 16.62 | |

| Faculty | Management/Business | 136 | 40.35 |

| Humanities and Social Science | 43 | 12.75 | |

| IT/Computing/Technology | 33 | 9.79 | |

| Engineering | 35 | 10.38 | |

| Science | 45 | 13.35 | |

| Medical | 18 | 5.34 | |

| Other | 27 | 8.04 | |

| Primary Research Interest | Field Survey | 236 | 70.03 |

| Secondary Data | 101 | 29.97 | |

| Total | 337 | 100.0 |

References

- Afrianty, T.W.; Artatanaya, I.G.; Burgess, J. Working from home effectiveness during COVID-19: Evidence from university staff in Indonesia. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2021, 27, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, J.-V.; Fadinger, H.; Schymik, J. My home is my castle–The benefits of working from home during a pandemic crisis. J. Public Econ. 2021, 196, 104373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arntz, M.; Ben Yahmed, S.; Berlingieri, F. Working from Home and COVID-19: The Chances and Risks for Gender Gaps. Intereconomics 2020, 55, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, L.; Li, T.; Xia, X.; Zhu, K.; Li, H.; Yang, X. How does working from home affect developer productivity?—A case study of Baidu during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2022, 65, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyan, C.B.; Begen, M.A. Working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic, its effects on health, and recommendations: The pandemic and beyond. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 58, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolisani, E.; Scarso, E.; Ipsen, C.; Kirchner, K.; Hansen, J.P. Working from home during COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons learned and issues. Manag. Mark. Chall. Knowl. Soc. 2020, 15, 458–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Seo, H.; Forbes, S.; Birkett, H. Working from Home during the COVID-19 Lockdown: Changing Preferences and the Future of Work; University of Kent: Canterbury, UK, 2020; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Dockery, M.; Bawa, S. Working from Home in the COVID-19 Lockdown: Transitions and Tensions; Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre: Bentley, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiadou, A.; Mouzakitis, S.; Askounis, D. Working from home during COVID-19 crisis: A cyber security culture assessment survey. Secur. J. 2021, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, C.; Grobovšek, J.; Poschke, M. Working from home across countries. COVID Econ. 2020, 1, 71–91. [Google Scholar]

- Guler, M.A.; Guler, K.; Gulec, M.G.; Ozdoglar, E. Working from Home During a Pandemic: Investigation of the Impact of COVID-19 on Employee Health and Productivity J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallman, D.M.; Januario, L.B.; Mathiassen, S.E.; Heiden, M.; Svensson, S.; Bergström, G. Working from home during the COVID-19 outbreak in Sweden: Effects on 24-h time-use in office workers. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.; Priestley, J.L.; Ishmakhametov, N.; Ray, H.E. “I’m not Working from Home, I’m Living at Work”: Perceived Stress and Work-Related Burnout before and during COVID-19. PsyArXiv 2020, 103, 2391–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, C.P.; Herring, M.P.; Lansing, J.; Brower, C.; Meyer, J.D. Working from Home and Job Loss Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic Are Associated with Greater Time in Sedentary Behaviors. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 597619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moretti, A.; Menna, F.; Aulicino, M.; Paoletta, M.; Liguori, S.; Iolascon, G. Characterization of Home Working Population during COVID-19 Emergency: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustajab, D.; Bauw, A.; Rasyid, A.; Irawan, A.; Akbar, M.A.; Hamid, M.A. Working from Home Phenomenon as an Effort to Prevent COVID-19 Attacks and Its Impacts on Work Productivity. Int. J. Appl. Bus. 2020, 4, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raišienė, A.G.; Rapuano, V.; Varkulevičiūtė, K.; Stachová, K. Working from Home—Who is Happy? A Survey of Lithuania’s Employees during the COVID-19 Quarantine Period. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysavy, M.D.T.; Michalak, R. Working from Home: How We Managed Our Team Remotely with Technology. J. Libr. Adm. 2020, 60, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaghaslah, D.; Alsayari, A. The Effects of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak on Academic Staff Members: A Case Study of a Pharmacy School in Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag. Health Policy 2020, 13, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank-Higher Education for the Twenty First Century Project & University Grants Commission. Induction Program for Academic Staff of Sri Lankan Universities—Training Manual. University Grants Commission Sri Lanka. 2012. Available online: https://www.ugc.ac.lk (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Mseleku, Z. A Literature Review of E-Learning and E-Teaching in the Era of COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2020, 5, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drašler, V.; Bertoncelj, J.; Korošec, M.; Žontar, T.P.; Ulrih, N.P.; Cigić, B. Difference in the Attitude of Students and Employees of the University of Ljubljana towards Work from Home and Online Education: Lessons from COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Wall, T.; Rayman-Bacchus, L.; Mifsud, M.; Pritchard, D.J.; Lovren, V.O.; Farinha, C.; Petrovic, D.S.; Balogun, A.-L. Impacts of COVID-19 and social isolation on academic staff and students at universities: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniffin, K.M.; Narayanan, J.; Anseel, F.; Antonakis, J.; Ashford, S.P.; Bakker, A.B.; Bamberger, P.; Bapuji, H.; Bhave, D.P.; Choi, V.K.; et al. COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieri, T.; Basso, G.; Scicchitano, S. Italian Workers at Risk during the COVID-19 Epidemic. Ital. Econ. J. 2021, 8, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekpanyaskul, C.; Padungtod, C. Occupational Health Problems and Lifestyle Changes Among Novice Working-From-Home Workers Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. Saf. Health Work 2021, 12, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, R.; Bakar, A.; Noh, I.; Mahyudin, H.A. Employees’ Job Satisfaction and Performance through working from Home during the Pandemic Lockdown. Environ. Behav. Proc. J. 2020, 5, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Green, P.; Rhodes, C.; Williams, A.; Chircop, J.; Spink, R.; Rawson, R.; Okere, U. Dealing with Isolation Using Online Morning Huddles for University Lecturers During Physical Distancing by COVID-19: Field Notes. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2020, 21, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, A. Novel Coronavirus Outbreak and Career Development: A Narrative Approach into the Meaning for Italian University Graduates. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Moreno-Rangel, A.; Baek, J.; Obeng, A.; Hasan, N.T.; Carrillo, G. Indoor Air Quality and Health Outcomes in Employees Working from Home during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Pilot Study. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, C.; Cortis, N.; Powell, A. University staff and flexible work: Inequalities, tensions and challenges. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2020, 43, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, L.; Butakhieo, N. The impact of working from home during COVID-19 on work and life domains: An exploratory study on Hong Kong. Policy Des. Pract. 2020, 4, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waizenegger, L.; McKenna, B.; Cai, W.; Bendz, T. An affordance perspective of team collaboration and enforced working from home during COVID-19. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couch, D.L.; O’Sullivan, B.; Malatzky, C. What COVID-19 could mean for the future of “work from home”: The provocations of three women in the academy. Gend. Work. Organ. 2020, 28, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, B.; Arthur, B. Academic motherhood during COVID-19: Navigating our dual roles as educators and mothers. Gender, Work Organ. 2020, 27, 887–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamura, E.; Tsustsui, Y. The impact of closing schools on working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence using panel data from Japan. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2021, 19, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, M.; Churchill, B. Caring during COVID-19: A gendered analysis of Australian university responses to managing remote working and caring responsibilities. Gender Work Organ. 2020, 27, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utoft, E.H. ‘All the single ladies’ as the ideal academic during times of COVID-19? Gend. Work Organ. 2020, 27, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanti, T.; Guidetti, G.; Mazzei, E.; Zappalà, S.; Toscano, F. Work from Home During the COVID-19 Outbreak: The Impact on Employees’ Remote Work Productivity, Engagement and Stress. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, e426–e432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toniolo-Barrios, M.; Pitt, L. Mindfulness and the challenges of working from home in times of crisis. Bus. Horiz. 2021, 64, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolor, C.W.; Dalimunthe, S.; Febrilia, I.; Martono, S. How to Manage Stress Experienced by Employees When Working from Home Due to the COVID-19 Virus Outbreak. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Tech-Nology 2020, 29, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Lucas, G.; Roll, S.C. Impacts of Working from Home during COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical and Mental Well-Being of Office Workstation Users. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwanto, A.; Asbari, M.; Fahlevi, M.; Mufid, A.; Agistiawati, E.; Cahyono, Y.; Suryani, P. Impact of Work from Home (WFH) on Indonesian Teachers Performance During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsen, C.; van Veldhoven, M.; Kirchner, K.; Hansen, J.P. Six Key Advantages and Disadvantages of Working from Home in Europe during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhumaid, K.; Ali, S.; Waheed, A.; Zaheed, E.; Habes, M. COVID-19 & Elearning: Perceptions &Attitudes of Teachers Towards E-Learning Acceptance in The Developing Countries. Multicult. Educ. 2020, 6, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, J. Education in and After COVID-19: Immediate Responses and Long-Term Visions. Postdigit. Sci. Educ. 2020, 2, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pokhrel, S.; Chhetri, R. A Literature Review on Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Teaching and Learning. High. Educ. Future 2021, 8, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Chinese University Students’ L2 Writing Feedback Orientation and Self-Regulated Learning Writing Strategies in Online Teaching During COVID-19. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2021, 30, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metscher, S.E.; Tramantano, J.S.; Wong, K.M. Digital instructional practices to promote pedagogical content knowledge during COVID-19. J. Educ. Teach. 2020, 47, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scull, J.; Phillips, M.; Sharma, U.; Garnier, K. Innovations in teacher education at the time of COVID19: An Australian perspective. J. Educ. Teach. 2020, 46, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, B. How Higher Education Promotes the Integration of Sustainable Development Goals—An Experience in the Postgraduate Curricula. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akour, A.; Al-Tammemi, A.B.; Barakat, M.; Kanj, R.; Fakhouri, H.N.; Malkawi, A.; Musleh, G. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Emergency Distance Teaching on the Psychological Status of University Teachers: A Cross-Sectional Study in Jordan. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 2391–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, R.; Schuck, R. “The Wall Now Between Us”: Teaching Math to Students with Disabilities During the COVID Spring of 2020. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2021, 30, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashokka, B.; Ong, S.Y.; Tay, K.H.; Loh, N.H.W.; Gee, C.F.; Samarasekera, D. Coordinated responses of academic medical centres to pandemics: Sustaining medical education during COVID-19. Med Teach. 2020, 42, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, W. COVID-19 and online teaching in higher education: A case study of Peking University. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garcez, A.; Silva, R.; Franco, M. Digital transformation shaping structural pillars for academic entrepreneurship: A framework proposal and research agenda. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 27, 1159–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sleiwah, A.; Mughal, M.; Hachach-Haram, N.; Roblin, P. COVID-19 lockdown learning: The uprising of virtual teaching. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2020, 73, 1575–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, F. Peshawar Dental College Remote Teaching and Supervision of Graduate Scholars in the Unprecedented and Testing Times. J. Pak. Dent. Assoc. 2020, 29, S36–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, A.S.; Blanco, G.L. “Love is calling”: Academic friendship and international research collaboration amid a global pandemic. Emot. Space Soc. 2021, 38, 100763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Haupt, J.P. Scientific globalism during a global crisis: Research collaboration and open access publications on COVID-19. High. Educ. 2020, 81, 949–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Silva, R.; Franco, M. Teaching and Researching in the Context of COVID-19: An Empirical Study in Higher Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, R.M.N.M.; Kumarasinghe, P.J.; Kumara, A.S. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Performance of Academic Personnel: An Open Access Systematic Literature Review Database (Version 1). South Fla. J. Dev. 2022, 3, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhry, A.; Kapoor, P.; Popli, D.B. Strengthening health care research and academics during and after COVID19 pandemic—An Indian perspective. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2020, 10, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, S.; Yadav, S.S. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Higher Education and Research. Indian J. Hum. Dev. 2020, 14, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, I.; Awang, Z. Knowledge sharing in multicultural organizations: Evidence from Pakistan. High. Educ. Skills. Work.-Based Learn. 2020, 10, 497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, M.F.; Tian, F. How academic leaders facilitate knowledge sharing: A case of universities in Hong Kong. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias Velásquez, R.M.A.; Mejía Lara, J.V. Knowledge management in two universities before and during the COVID-19 effect in Peru. Technol. Soc. 2020, 64, 101479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Social media as a tool of knowledge sharing in academia: An empirical study using valance, instrumentality and expectancy (VIE) approach. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 2531–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J. The COVID-19 infodemic: The role and place of academics in communicating science to the public. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.08787. [Google Scholar]

- University Grants Commission-Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka University Statistics; University Grants Commission: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2020; pp. 101–107. Available online: https://www.ugc.ac.lk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2301%3Asri-lanka-university-statistics-2020&catid=55%3Areports&Itemid=42&lang=en (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Kumara, A.S.; Sachitra, V. Modeling the participation in physical exercises by university academic community in Sri Lanka. Health Educ. 2021, 121, 504–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, D.L.; Coombs, C.; Constantiou, I.; Duan, Y.; Edwards, J.S.; Gupta, B.; Lal, B.; Misra, S.; Prashant, P.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on information management research and practice: Transforming education, work and life. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valantinaitė, I.; Sederevičiūtė-Pačiauskienė, Ž. The Change in Students’ Attitude towards Favourable and Unfavourable Factors of Online Learning Environments. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, L.; Abós, A.; Diloy-Peña, S.; Gil-Arias, A.; Sevil-Serrano, J. Can a Hybrid Sport Education/Teaching Games for Understanding Volleyball Unit Be More Effective in Less Motivated Students? An Examination into a Set of Motivation-Related Variables. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidou, I.; Dragicevic, N.; Tsui, E. A Multi-Dimensional Hybrid Learning Environment for Business Education: A Knowledge Dynamics Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looi, K.H.; Wye, C.-K.; Bahri, E.N.A. Achieving Learning Outcomes of Emergency Remote Learning to Sustain Higher Education during Crises: An Empirical Study of Malaysian Undergraduates. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Islam, A.Y.M.A.; Gu, X.; Spector, J.M. Online learning satisfaction in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A regional comparison between Eastern and Western Chinese universities. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 6747–6769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firmansyah, R.; Putri, D.M.; Wicaksono, M.G.S.; Putri, S.F.; Widianto, A.A.; Palil, M.R. Educational Transformation: An Evaluation of Online Learning Due To COVID-19. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2021, 16, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Garbuja, C.K.; Rai, G. Nursing Students’ Perception of Online Learning Amidst COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Lumbini Med. Coll. 2021, 9, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Sawarkar, G.; Sawarkar, P.; Kuchewar, V. Ayurveda students’ perception toward online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, D. The impact of online learning during COVID-19: Students’ and teachers’ perspective. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2020, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khuluqo, I.; Ghani, A.R.A.; Fatayan, A. Postgraduate students’ perspective on supporting “learning from home” to solve the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 2021, 10, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javad Koohsari, M.; Nakaya, T.; Shibata, A.; Ishii, K.; Oka, K. Working from Home After the COVID-19 Pandemic: Do Company Employees Sit More and Move Less? Sustainability 2021, 13, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacini, L.; Gallo, G.; Scicchitano, S. Working from home and income inequality: Risks of a ‘new normal’ with COVID-19. J. Popul. Econ. 2020, 34, 303–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, G.M. Does online technology provide sustainable HE or aggravate diploma disease? Evidence from Bangladesh—A comparison of conditions before and during COVID-19. Technol. Soc. 2021, 66, 101677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, G.M.; Parvin, M. Can online higher education be an active agent for change?—Comparison of academic success and job-readiness before and during COVID-19. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 172, 121008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Feng, B. Digital inequality in online reciprocity between generations: A preliminary exploration of ability to use communication technology as a mediator. Technol. Soc. 2021, 66, 101609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M. Do Urbanized Socioeconomic Background or Education Programs Support Engineers for Further Advancement? Int. J. Educ. Reform 2021, 30, 344–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, R.; Catalano, G.; Daraio, C.; Gregori, M.; Moed, H.F. Studying the heterogeneity of European higher education institutions. Scientometrics 2020, 125, 1117–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, S. Limitations of human capital theory. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 44, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, P.; Liyanage, K.; Ushiogi, M.; Muta, H. Analysis of Policies for Allocating University Resources in Het-erogeneous Social Systems: A Case Study of University Admissions in Sri Lanka. High. Educ. 1997, 34, 437–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Chen, S.; Nieminen, M. The Effects of Demographics, Technology Accessibility, and Unwillingness to Communicate in Predicting Internet Gratifications and Heavy Internet Use Among Adolescents. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2015, 34, 278–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Khalil, A.; Lonka, K.; Tsai, C.-C. Do educational affordances and gratifications drive intensive Facebook use among adolescents? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Alsumait, A. Examining the Educational User Interface, Technology and Pedagogy for Arabic Speaking Children in Kuwait. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Interaction Design in Educational Environments, Wrocław, Poland, 28 June 2012; pp. 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, K.; Chen, S.; Rothmann, S.; Dhir, A.; Pallesen, S. Investigating the relation among disturbed sleep due to social media use, school burnout, and academic performance. J. Adolesc. 2020, 84, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, T. How distance education students perceive the impact of teaching videos on their learning. Open Learn. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2019, 35, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, G.M.; Asimiran, S. Online technology: Sustainable higher education or diploma disease for emerging society during emergency—Comparison between pre and during COVID-19. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 172, 121034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N | Mean | s.d. | Min | Max | Sum_w | Var | Skewness | Kurtosis | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WFH | 337 | 3.568 | 0.585 | 2 | 5 | 337 | 0.342 | 0.284 | 3.036 | 1203 |

| OTT | 337 | 3.127 | 0.513 | 1.500 | 4.750 | 337 | 0.263 | −0.285 | 3.307 | 1054 |

| OTRSC | 337 | 2.888 | 0.480 | 1.571 | 4.071 | 337 | 0.230 | 0.117 | 3.435 | 973.2 |

| OTDOK | 337 | 1.737 | 0.664 | 1 | 4 | 337 | 0.441 | 1.029 | 3.748 | 585.4 |

| Variable | Reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha) | Number of Items |

|---|---|---|

| OTT | 0.7812 | 12 |

| OTRSC | 0.7320 | 14 |

| OTDOK | 0.9234 | 13 |

| WFH | 0.8297 | 10 |

| VARIABLES | Model | Model | Model | Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Gender | 0.0300 | 0.128 * | 0.130 | |

| (0.0584) | (0.0725) | (0.0872) | ||

| Education | −0.116 *** | −0.0850 ** | −0.0588 | |

| (0.0324) | (0.0378) | (0.0392) | ||

| Experience | −0.000520 | −0.0757 *** | −0.0669 ** | |

| (0.0211) | (0.0257) | (0.0308) | ||

| University Sector | 0.0434 | 0.0115 | 0.0711 | |

| (0.0743) | (0.117) | (0.136) | ||

| Research Interest | −0.0321 | 0.156 * | 0.205 * | |

| (0.0640) | (0.0887) | (0.116) | ||

| OTT | 0.365 *** | 0.347 *** | 0.490 *** | −0.0490 |

| (0.0657) | (0.0599) | (0.0804) | (0.120) | |

| OTRSC | 0.339 *** | 0.345 *** | 0.320 *** | 0.581 *** |

| (0.0699) | (0.0703) | (0.0859) | (0.102) | |

| OTDOK | −0.294 *** | −0.242 *** | −0.198 *** | −0.525 *** |

| (0.0421) | (0.0497) | (0.0604) | (0.0777) | |

| Constant | 1.957 *** | 2.248 *** | 1.824 *** | 3.176 *** |

| (0.185) | (0.213) | (0.287) | (0.360) | |

| Observations | 337 | 337 | 201 | 86 |

| R-squared | 0.249 | 0.293 | 0.394 | 0.546 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rathnayake, N.M.; Kumarasinghe, P.J.; Kumara, A.S. How Do Different Types of University Academics Perceive Work from Home Amidst COVID-19 and Beyond? Sustainability 2022, 14, 4868. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094868

Rathnayake NM, Kumarasinghe PJ, Kumara AS. How Do Different Types of University Academics Perceive Work from Home Amidst COVID-19 and Beyond? Sustainability. 2022; 14(9):4868. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094868

Chicago/Turabian StyleRathnayake, Nilmini M., Pivithuru J. Kumarasinghe, and Ajantha S. Kumara. 2022. "How Do Different Types of University Academics Perceive Work from Home Amidst COVID-19 and Beyond?" Sustainability 14, no. 9: 4868. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094868

APA StyleRathnayake, N. M., Kumarasinghe, P. J., & Kumara, A. S. (2022). How Do Different Types of University Academics Perceive Work from Home Amidst COVID-19 and Beyond? Sustainability, 14(9), 4868. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14094868